Old Valthungian: Difference between revisions

Bpnjohnson (talk | contribs) |

Bpnjohnson (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2,192: | Line 2,192: | ||

uns þetij skulans sijaem svasvei jah vijs | uns þetij skulans sijaem svasvei jah vijs | ||

afleitam þaem skulam unsaraem jah nij bringae[s] | afleitam þaem skulam unsaraem jah nij bringae[s] | ||

uns in fraestubvnjae ak | uns in fraestubvnjae ak leaosij uns af þatma | ||

ubvilin untei þijna ist þjuðangarði jah mahts | ubvilin untei þijna ist þjuðangarði jah mahts | ||

jah vulðus in aejugins · ahmein | jah vulðus in aejugins · ahmein | ||

. | . | ||

Revision as of 21:57, 25 November 2019

| Old Valthungian | |

|---|---|

| Valðungiskou Rasta | |

| Pronunciation | [/ˈwɑl.ðʊŋ.gɪs.koː ˈrɑs.tɑ/] |

| Created by | BenJamin P. Johnson, creator of: |

| Date | 2018 |

| Setting | Northern Italy |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | qgt |

| BRCL | grey |

Old Valthungian represents a period in the development of the Valthungian language lasting from around 800‒1200ad marked mainly by changes to geminates and intervocalic consonants, as well as the introduction of Germanic ī/j-umlaut and some small but important changes to all of the vowels. Though this is a range which experienced many changes, the most representative example of “Old Valthungian” is the language as it is captured in a few surviving texts believed to date to around 950‒975ad

Major Changes from Griutungi (and Earlier) to Old Valthungian

N.B.: This article uses a phonetic feature notation shorthand in which all described features are limited to three characters. Please refer to the legend here.

Variation and Expansion of East Germanic Glide Insertion (~400ad ‒ [remains persistent])

Glide Insertion in East Germanic developed differently in Gothic and Griutungi. In Gothic,

it applied optionally between two consecutive vowels only after a stressed vowel when one

of the vowels was /i(ː)/ (e.g. saian /sɛ̄an/ ‘to sow’ could have a third person singular

of either saiiþ /sɛ̄iθ/ or saijiþ /sɛ̄jiθ/. In Griutungi, however, it applies to both

front and back glide insertion (/j/ and /w/), is not optional, and applies to any consecutive

vowels where one of the vowels is not +low, so both the infinitive and third

person singular present indicative of ‘sew’ show glide insertion: sǣjan, sǣjiþ.

This rule remains persistent in the grammar of Griutungi through Old, Middle, and even Modern Valthungian, though the environment of the rule changes slightly as the language changes.

| Ø | → | j | / | V | ___ | + V | |||

-bck

|

|||||||||

-low

|

and

| Ø | → | w | / | V | ___ | + V | |||

+bck

|

|||||||||

-low

|

“A glide (j) is inserted between a non-low front vowel and a following vowel.”

“A glide (w) is inserted between a non-low back vowel and a following vowel.”

To describe it differently, a glide must be inserted between two consecutive vowels, the value of which (front or back) is determined by the value of the first vowel.

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *sōwilō /soːwiloː/ |

sauil /sɔː.il/ |

*sōwila /soːwilɑ/ |

sougyila /so(ː)u̯ɣilɑ/ |

sougila /sɔu̯ɡilɑ/ |

sōgila /sau̯ɡilɑ/ |

‘sun’ |

| *sǣ(j)aną → *sǣ(j)idi /sɛː(j)ɑnɑ̃ → sǣ(j)iði/ |

saian → saijiþ[1] /sɛːɑn → sɛːjiθ/ |

*sǣjan → *sǣjiþ /sɛːjɑn → sɛːjiθ/ |

saegjan → saegjiþ /sɛːɣjɑn → sɛːɣjiθ/ |

sǣgzjen → sǣgzjiþ /se̞ːɡʒjɛn → se̞ːɡʒjiθ/ |

sǣǧin → sǣǧiþ /se̞ːʤin → se̞ːʤiθ/ |

‘to sow’ → ‘sows’ (“soweth”) |

| *rō(w)aną → *rō(w)idi /roː(w)ɑnɑ̃ → roː(w)iði/ |

*rauan → *rauiþ /rɔːɑn → rɔːiθ/ |

*rōwan → *rōwiþ /roːwɑn → roːwiθ/ |

*rougyan → rougyiþ /rou̯ɣɑn → rou̯ɣiθ/ |

rougan → rougiþ /rɔu̯ɡn̩ → rɔu̯ɡiθ/ |

rōgna → rōgiþ /rau̯ɡnɑ → rau̯ɡiθ/ |

‘to row’ → ‘rows’ (“roweth”) |

Germanic Obstruent Devoicing (< 400ad ‒ [remains persistent])

Germanic Obstruent Devoicing is a rule inherited from Proto-Germanic which remains persistent in the grammar throughout the transition to East Germanic, Griutungi, Old, Middle, and modern Valthungian.

| C | → | -vox

|

/ | ___ { # or | -vox

|

|||||||

+vox

|

||||||||||||

+obs

|

||||||||||||

+ctn

|

“A voiced continuant obstruent (i.e. β, ð, or ɣ) becomes devoiced (f, θ, or x, respectively) when word-final or before an unvoiced consonant.”

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *gibaną → *gaf /ɡiβɑnɑ̃ → gɑɸ/ |

giban → gaf /ɡiβɑn → gɑɸ/ |

*giban → *gaf /ɡiβɑn → gɑɸ/ |

gibvan → gaf /ɡiβɑn → gɑɸ/ |

givan → gavf /ɡivn̩ → ɡɑf/ |

givna → gaf /ɡivn̩ɑ → ɡɑf/ |

‘to give’ → ‘gave’ |

| *rǣdaną → *rǣþ /rɛːðɑnɑ̃ → rɛːθ/ |

rēdan → rēþ /reːðɑn → reːθ/ |

*rēdan → *rēþ /reːðɑn → reːθ/ |

reiðan → *reiþ /rei̯ðɑn → rei̯θ/ |

reiðan → reiþ /rɛi̯ðn̩ → rɛi̯θ/ |

rēðna → rēþ /rai̯ðnɑ → rai̯θ/ |

‘to speak’ → ‘speak!’ |

| *ōganą → *ahtǭ /oːɣɑnɑ̃ → ɑxtõː/ |

ōgan → ōhta /oːɣɑn → oːhtɑ/ |

*ōgan → *ōhta /oːɣɑn → oːxtɑ/ |

*ougyan → *ouhta /ou̯ɣɑn → ou̯xtɑ/ |

ougan → oufta /ɔu̯ɡn̩ → ɔu̯ɸtɑ/ |

ōgna → ōfta /au̯gnɑ → au̯ftɑ/ |

‘to fear’ → ‘I feared’ |

Geminate Simplification I (< 400ad)

| Cː | → | C | / | ___ | { C, # |

“A geminate becomes a single consonant when it occurs before another consonant or a word boundary.”

This may have happened in two stages, the first being pre-consonantal and later before a word boundary, as evidenced by the retention of some word-final consonants in Gothic.

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *swemmaną → *swamm /swemːɑnɑ̃ → swɑm(ː)/ |

*swimman → *swamm /swimːɑn → swɑm(ː)/ |

*swimman → *swam /swimːɑn → swɑm/ |

svitman → svam /switmɑn → swɑm/ |

switman → swam /switmɑn → swɑm/ |

switman → swam /switmɑn → swɑm/ |

‘to swim’ → ‘swam’ |

| *kunnaną → *kunþǭ /kunːɑnɑ̃ → kunθõː/ |

kunnan → kunþa /kunːɑn → kunθɑ/ |

*kunnan → *kunþa /kunːɑn → kunθɑ/ |

kutnan → kunþa /kutnɑn → kunθɑ/ |

kutnan → kunþa /kutnɑn → kunθɑ/ |

kutnan → kunþa /kutnɑn → kunθɑ/ |

‘to be able’ → ‘could’ |

| *wessǭ → gawessaz /wesːõː → gɑˈwesːɑz/ |

wissa → gawiss /wisːɑ → gaˈwis(s)/ |

wissa → gawis /wisːɑ → gaˈwis/ |

vihsa → gavis /wihsɑ → gɑˈwis/ |

wīsa → gawis /wiːsɑ → gɑˈwis/ |

wīsa → gawís /wiːsɑ → gɑˈwis/ |

‘I knew’ → ‘certain’ |

Spirantization of Voiced Stops

This is a change that had likely already started long before the division between Gothic and Griutungi, and probably happened similarly in Gothic as well. In the Griutungi lineage, it occurred in three distinct stages:

Stage I ( < 400ad)

Intervocalic voiced stops (i.e. /b/, /d/, and /g/) became spirantized: /β/, /ð/, and /ɣ/. This likely happened quite early, perhaps already by Proto-Germanic times, and was clearly in operation in Gothic as well.

| C | → | +ctn

|

/ | V ___ V | |||||

+vox

|

|||||||||

-ctn

|

“A voiced non-continuant (i.e. stop) consonant becomes continuant (i.e. fricative) when intervocalic.”

In more direct terms:

| b | → | β | / | any vowel } ___ { any vowel | |

| d | → | ð | |||

| g | → | ɣ |

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *hlaibai /xlɛːβɑi̯/ |

hlaiba /hlɛːβɑ/ |

*hlǣba /xlɛːβɑ/ |

hlaebva /xlɛːβɑ/ |

þlǣva /θle̞ːvɑ/ |

þlǣva /θle̞ːvɑ/ |

‘loaf.dat’ |

| *mōdǣr /moːðɛːr/ |

*mōdar /moːðɑr/ |

*mōdar /moːðɑr/ |

mouðar /mou̯ðɑr/ |

mouður /mɔu̯ðr̩/ |

mōðra /mau̯ðrɑ/ |

‘mother’ |

| *ōganą /oːɣɑnɑ̃/ |

ōgan /oːɣɑn/ |

*ōgan /oːɣɑn/ |

*ougyan /ou̯ɣɑn/ |

ougan /ɔu̯ɡn̩/ |

ōgna /au̯ɡnɑ/ |

‘to fear’ |

Stage II ( ~ 400ad)

The same process occurred, but in Stage II the environment changes to include /l/ and /r/ before the stop and any sonorant (i.e. /l/, /r/, /m/, or /n/) after. This likely occurred before or during the time of Griutung proper, and may have happened in a similar environment in Gothic.

| C | → | +ctn

|

/ | +son

|

___ | +son

|

|||||||||

+vox

|

-nas

|

||||||||||||||

-ctn

|

“A voiced non-continuant (i.e. stop) consonant becomes continuant (i.e. fricative) when preceded by a vowel or a liquid and followed by any sonorant (a vowel, a liquid, or a nasal).”

In more direct terms:

| b | → | β | / | V, l, r } ___ { V, l, r, m, n | |

| d | → | ð | |||

| g | → | ɣ |

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *seldalīkaz /seldɑliːkɑz/ |

sildaleiks /sildɑliːks/ |

*sildalīks /sildɑliːks/ |

silðalijks /silðɑliːks/ |

silðalīks /silðɑliːks/ |

silðaliks /silðɑliks/ |

‘wonderful’ |

| *burgīniz /burɡiːniz/ |

baurgeins /bɔrɡiːns/ |

*borgīns /bɔrɡiːns/ |

*beorgyijns /bœrɣiːns/ |

boergīns /bø̞rɡiːns/ |

bœrgins /bø̞rɡins/ |

‘protection’ |

| *ebnaz /ebnaz/ |

ibns /ibn̩s/ |

*ibns /ibn̩s/ |

ibvns /iβn̩s/ |

ivans /ivn̩s/ |

ivnas /ivnɑs/ |

‘even’ |

Stage III ( ~ 500ad)

In the final stage, which happened significantly after the earlier two (probably not before 900ad), the unvoiced continuants /f/ and /θ/, became voiced in the same environment as stage II.

| C | → | +vox

|

/ | +son

|

___ | +son

|

|||||||||

-vox

|

-nas

|

||||||||||||||

+ctn

|

|||||||||||||||

| ( | -bck

|

) |

“An unvoiced non-back continuant (i.e. fricative other than /h/[2]) consonant becomes voiced when preceded by any non-nasal sonorant and followed by any' sonorant.”

In more direct terms:

| f | → | β | / | V, l, r } ___ { V, l, r, m, n | |

| þ | → | ð |

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *walþuz /wɑlθuz/ |

*walþus /wɑlθus/ |

*walþus /wɑlθus/ |

valðus /wɑlðus/ |

walðus /wɑlðus/ |

walðus /wɑlðus/ |

‘forest’ |

| *wulfis /wulɸis/ |

*wulfis /wulɸis/ |

*wulfis /wulɸis/ |

vulbvis /wulβis/ |

wulvis /wulvis/ |

wulvis /wulvis/ |

‘wolf.gen’ |

Stop Insertion after Nasals

Building on an Late Indo-European rule that had some implications for the development of Proto-Germanic, this change is reflected in some Gothic spellings, but has not completely come into effect yet. The reconstruction of Griutungi posits the change as complete.

| Ø | → | C | / | +son

|

___ | +son

|

|||||||||||

-ctn

|

+nas

|

!+ | -nas

|

||||||||||||||

+vox

|

“A voiced stop is inserted between a nasal and a following liquid (where there is no morpheme boundary present).”

In other words, b is inserted after m before l or r, and d is inserted after n in the same environment, as long as the nasal and the following liquid are not separated by a word or morpheme boundary (so, for instance, un+rēkīs ‘non-toxic’ does not become **undrēkīs because un- is a separate morpheme). In all:

- ml → mbl

- mr → mbr

- nl → ndl

- nr → ndr

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *temrijaną /temrijɑnɑ͂/ |

tim(b)rjan /tim(b)rjɑn/ |

*timbrjan /timbrjɑn/ |

*timbrjan / timbrjɑn/ |

timbrjen / timbriən/ |

timbrin /timbrin/ |

‘to construct’ |

| *þunraz /θunrɑz/ |

*þunrs /θunr̩s/ |

*þundrs /θundr̩s/ |

*þundrs /θundr̩s/ |

þundr /θundr̩/ |

þundra /θundrɑ/ |

‘thunder’ |

| *sumaraz /sumɑrɑz/ |

*sumrs /sumr̩s/ |

*sumbrs /sumbr̩s/ |

sumbrs /sumbr̩s/ |

sumbr /sumbr̩/ |

sumbra /sumbrɑ/ |

‘summer’ |

Change of /fl/ to /θl/

This is an expansion of an earlier change in East Germanic in which /fl/ became /θl/ in certain questionable environments which may or may not have included back vowels and/or velar consonants (there are only a handful of attested words where this change appears in writings of the time). Shortly after the Griutungi split, all remaining word-initial instances of /fl/ became /θl/.

| f | → | þ | / | # ___ l |

“Word-initial f becomes þ before l.”

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *fleuganą /fleuɣɑnɑ͂/ |

*þliugan /θliu̯ɣɑn/ |

*þliugan /θliu̯ɣɑn/ |

þljugyan /θljuɣɑn/ |

þljugan /θljuɡn̩/ |

þljugna /θljuɡnɑ/ |

‘to fly’ |

| *flehtiz /flehtiz/ |

þlaihts /θlɛhts/ |

*þlehts /θlehts/ |

*þlehts /θlehts/ |

þlaets /θleːts/ |

þlǣts /θle̞ːts/ |

‘comfort’ |

| *flōduz /floːðuz/ |

flōdus /floːðus/ |

*flōdus /floːðus/ |

þlouðus /θlou̯ðus/ |

þlōðus /θlɔu̯ðus/ |

þlōðus /θlau̯ðus/ |

‘river’ |

Voicing and Devoicing of Consonant Clusters

Voicing of Word-Final /s/ after a Voiced Consonant (~550ad)

Word-final /s/ was voiced after /b/, /d/, and /g/. (And thus I dispense with the mystery of what the phonetic and phonemic value of the /g/ of Gothic dags might have been!)

| s | → | z | / | C | ___ | # | |||

+vox

|

|||||||||

-ctn

|

“Word-final s becomes voiced when following a voiced stop.”

In more direct terms:

| s | → | z | / | b, d, g } | ___ | # |

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *þarbaz /θɑrbɑz/ |

þarbs /θɑrbs/ |

*þarbs /θɑrbs/ |

þarbz /θɑrbʐ/ |

þarbž /θɑrbʒ/ |

þarbž /θɑrbʒ/ |

‘needy, needful’ |

| *wendaz /wendaz/ |

winds /winds/ |

*winds /winds/ |

vindz /windʐ/ |

windž /windʒ/ |

winǧ /winʤ/ |

‘wind’ |

| *dagaz /dɑɣɑz/ |

dags /dɑɡs/ |

*dags /dɑɡs/ |

dagz /dɑɡʐ/ |

dagž /dɑɡʒ/ |

daǧ /dɑʤ/ |

‘day’ |

Devoicing of Word-Internal Obstruent Clusters

Word-internal obstruent clusters (specifically z followed by a voiced stop consonant) are devoiced.

| z | C | → | -vox

|

/ | V ___ V | |||||

+vox

|

||||||||||

-ctn

|

“A cluster consisting of z followed by a voiced stop becomes unvoiced when intervocalic.”

In more direct terms:

| zb | → | sp | / | any vowel } ___ { any vowel | |

| zd | → | st | |||

| zg | → | sk |

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *razdō /rɑzdoː/ |

razda /rɑzdɑ/ |

razda /rɑzdɑ/ |

rasta /rɑstɑ/ |

rasta /rɑstə/ |

rasta /rɑstɑ/ |

‘speech’ |

| *azgǭ /ɑzɡõː/ |

azgō /ɑzɡoː/ |

*azgō /ɑzɡoː/ |

askou /ɑskoː/ |

asko /ɑsko/ |

aska /ɑskɑ/ |

‘ashes’ |

| Grk. πρεσβύτεροι /prɛzbytɛriː/ |

praizbwtairei /prɛːzbʏtɛriː/ |

*prezbyterī /prɛːzbʏtɛriː/ |

*prespyterij /prespʏteriː/ |

prespiterī /prespiteriː/ |

prespiteri /prespiteri/ |

‘council of elders’ |

Clisis and Lexicalization

Between 600 and 850ad, many word boundaries were blurred in the Old Valthungian language. Several clitics became particles, while other words became inseparable.

Lexicalization of East Germanic Clitics

Several clitics that were common in earlier East Germanic languages became lexicalized, usually optionally. Often, words commonly combined with the clitics existed in two forms, leading to sometimes dramatic sound changes later on, e.g. þōzī ‘they who’ (Gothic þōzei) became optionally þōzī or þōs ī, which after Umlaut became þø̄zī [θøːziː] and þōs ī [θou̯s iː], and eventually modern Valthungian þœ̄ži [θø̞ːʒi] and þōs ī [θau̯s iː].

-ī# → #ī#

-u- → #u#

-uh# → #uh#

-hun# → #hun#

#ga- → #ga#

Cliticization of Prepositions, Particles, and Determiners

While these clitics were lexicalizing, other particles – mainly pronouns, prepositions, and determiners – were fusing. Particularly combinations of prepositions followed by articles or pronouns, and dative pronouns followed by accusative pronouns. (More about this later.)

Changes to Geminate Consonants

Between 500‒650ad all of the geminate consonants inherited from Griutungi were condensed to a single consonant. This also put an end to a persistent rule inherited from Proto-Germanic whereby geminate consonants collapsed before and obstruent or a word-boundary, there being no more geminate consonants to encounter such an environment.

Changes to Geminate Obstruents

In geminate obstruents – that is, geminate stops and fricatives – the first obstruent of the pair is lenited to /h/. (Later, in a separate process of h-deletion, these are eliminated completely.)

| CC | → | hC | |||

-son

|

To put it another way:

pp → hp

tt → ht

kk → hk

bb → hb

dd → hd

gg → hg*

ff → hf

þþ → hþ

ss → hs

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wissō /wisːo͂ː/ |

wissa /wisːɑ/ |

wissa /wisːɑ/ |

vihsa /wihsɑ/ |

wīsa /wiːsɑ/ |

wīsa /wiːsɑ/ |

‘knew’ |

| attô /ɑtːoːː/ |

atta /ɑtːɑ/ |

atta /ɑtːɑ/ |

ahta /ɑhtɑ/ |

āta /ɑːtɑ/ |

āta /ɑːtɑ/ |

‘Dad’ |

| addją, addjai /ɑdːjɑ͂, ɑd:jai/ |

addi, addja /ɑd:i, ɑd:jɑ/ |

addi, addja /ɑd:i, ɑd:jɑ/ |

ahdi, ehdja /ɑhdi, ɛhdi/ |

ādi, ǣdžja /ɑːdi, e̞ːdʒjɑ/ |

āde, ǣǧa /ɑːde̞, e̞ːʤɑ/ |

‘egg, egg.dat’ |

Changes to Geminate Sonorants

In geminate sonorants – that is, geminate nasals and liquids – the first sonorant of the pair becomes -son, -vox and -ctn; that is, it is replaced by an unvoiced stop (in the same place of articulation).

Stage I

| CC | → | C | C | |||||

+son

|

-son

|

|||||||

-vox

|

||||||||

-ctn

|

To put it another way:

mm → pm

nn → tn

rr → tr

ll → tl

Stage II

Much later, perhaps as late as 750 or 800ad, pm shifts to tm, but only in words which had previously contained geminate mm

pm → tm

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rennaną /renːɑnɑ͂/ |

rinnan /rinːɑn/ |

rinnan /rinːɑn/ |

ritnan /ritnɑn/ |

ritnan /ritnɑn/ |

ritnan /ritnɑn/ |

‘to run’ |

| allaz, allai /ɑlːɑz, ɑlːai/ |

alls, alla /ɑl(ː)s, ɑlːɑ/ |

alls, alla /ɑl(ː)s, ɑlːɑ/ |

als, atla /ɑls, ɑtlɑ/ |

als, atla /ɑls, ɑtlɑ/ |

als, atla /ɑls, ɑtlɑ [ɑdɮɑ]/ |

‘all, all.dat’ |

| þammai /θɑmːai/ |

þamma /θɑmːɑ/ |

þamma /θɑmːɑ/ |

þapma → þatma /θɑpmɑ → θɑtmɑ/ |

þatma /θɑtmɑ/ |

þatma /θɑtmɑ/ |

‘the.dat’ |

Vowel Changes

Lengthening of Word-Final Stressed Vowels

Vowel lengthening applies mainly to monosyllabic function words such as articles, pronouns, and prepositions.

| V | → | +lng

|

/ | ___ # | |||||

+str

|

|||||||||

-lng

|

“Stressed short vowels become long when word-final.”

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bi /bi/ |

bi /bi/ |

bi /bi/ |

bij /biː/ |

bī /biː/ |

bī /biː/ |

‘by’ |

| þu /θu/ |

þu /θu/ |

þu /θu/ |

þuv /θuː/ |

þū /θuː/ |

þū /θuː/ |

‘you’ |

| sa /sɑ/ |

sa /sɑ/ |

sa /sɑ/ |

saa /sɑː/ |

sā /sɑː/ |

sā /sɑː/ |

‘the’ |

Lengthening of /ij/

All instances of ij become lengthened. (More accurately, ij becomes ī, and then the persistent glide-insertion rule immediately restores j before a following vowel, but it's simpler to just say that ij becomes īj.) NB: Because of the orthography of Old Valthungian, in which the long vowel /iː/ is represented by 〈ij〉, this change is not represented in the orthography, but is indicated by other changes; for example, this change must have occurred before long diphthong breaking.

| i | → | ī | / | ___ j |

“Short i is lengthened before j.”

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ejō /ejoː/ |

ija /ijɑ/ |

ija /ijɑ/ |

ija /iːjɑ/ |

īja /iːjɑ/ |

īja /iːjɑ/ |

‘her’ |

| sneiwan /ˈsneiwɑn/ |

sneiwan /ˈsniːwɑn/ |

snīwan /ˈsniːwɑn/ |

snijugyan /ˈsniːjuɣɑn/ |

snījugn /ˈsniːjuɡn̩/ |

snījugna /ˈsniːjuɡnɑ/ |

‘to snow’ |

| frejōndz /frejoːndz/ |

frijōnds /frijoːnds/ |

frijōnþs /frijoːnθs/ |

frijounþs /friːjoːnθs/ |

frījonþs /friːjonθs/ |

frīnþs /friːnθs/ |

‘friend’ |

Reversal of High Diphthong Altitude Trajectory

The high rising diphthong iu becomes a falling diphthong and is reanalyzed as a glide.

| iu | → | ju |

“i becomes j before u.”

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| deupiþō /deu̯piθoː/ |

diupiþa /diu̯piθɑ/ |

diupiþa /diu̯piθɑ/ |

djupiða /djupiðɑ/ |

džjupiða /ʤjupiðɑ/ |

ǧupiða /ʤupiðɑ/ |

‘depth’ |

| newun /newun/ |

niun /niu̯n/ |

niun /niu̯n/ |

njun /njun/ |

njun /njun/ |

njun /njun/ |

‘nine’ |

| uppai /uppai̯/ |

iupa /iu̯pɑ/ |

iupa /iu̯pɑ/ |

jupa /jupɑ/ |

jupa /jupɑ/ |

jupa /jupɑ/ |

‘up, above’ |

Umlaut

Ī/J-Umlaut (hereafter referred to merely as “Umlaut,” as no other types of Umlaut occur in the diachrony of the Valthungian language) occurs fairly early in comparison to some of the other Germanic languages, though it has some particular quirks that other Germanic languages lacked.

| V | → | -bck

|

/ | ___ | C…*{ī,j | |||||

+str

|

*Where … can only cross one syllable boundary. | |||||||||

+bck

|

||||||||||

“A stressed back vowel becomes fronted when ī or j occurs in the following syllable.”

This rule remains productive in the grammar at least through the change of iu to ju, because short i does not trigger umlaut. However, the vowel in ju from earlier iu is not subject to umlaut.

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sandijaną /ˈsɑndijɑnɑ̃/ |

sandjan /ˈsɑndjɑn/ |

sandjan /ˈsɑndjɑn/ |

sendjan /ˈsɛndjɑn/ |

sendžjen /ˈsenʤjən/ |

senǧin /ˈsenʤin/ |

‘to send’ |

| gahanhijô /gɑˈhɑnhijoːˑ/ |

gahāhjō /gɑˈhɑːhjoː/ |

gahāhjō /gɑˈhɑːhjoː/ |

gahaehjou /gɑˈhɛːhjoː/ |

gahǣšjo /gɑˈhe̞ːçjo/ |

gahǣša /gɑˈhe̞ːʃɑ/ |

‘orderly’ |

| auþijaz /ˈauθijaz/ |

auþeis /ˈɔːθiːs/ |

ǭþīs /ˈɔːθiːs/ |

eaoðijs /ˈœːðiːs/ |

œ̄ðīs /ˈø̞ːðiːs/ |

œ̄ðis /ˈø̞ːðis/ |

‘deserted’ |

| wurkijaną /ˈwurkijɑnɑ̃/ |

waurkjan /ˈwɔrkjɑn/ |

workjan /ˈwɔrkjɑn/ |

weorkjan /ˈwœrkjɑn/ |

wœrkšjen /ˈwø̞rkʃjən/ |

wœrčin /ˈwø̞rʧin/ |

‘to work’ |

| dōmijaną /ˈdoːmijɑnɑ̃/ |

dōmjan /ˈdoːmjɑn/ |

dōmjan /ˈdoːmjɑn/ |

deoumjan /ˈdøːmjɑn/ |

dœymjen /ˈdø̞ymjən/ |

dœumin /ˈdœy̑min/ |

‘to judge’ |

| sunjō /ˈsunjoː/ |

sunja /ˈsunjɑ/ |

sunja /ˈsunjɑ/ |

seunja /ˈsynjɑ/ |

synja /ˈsynjɑ/ |

synia /ˈsyniɑ/ |

‘truth’ |

| garūnijai /gɑˈruːnijai̯/ |

garūnja /gɑˈruːnjɑ/ |

garūnja /gɑˈruːnjɑ/ |

gareuvnja /gɑryːnjɑ/ |

garȳnja /gɑˈryːnjɑ/ |

garȳnia /gɑˈryːniɑ/ |

‘mystery.dat’ |

Change of Word-Initial /j/ to /g/

This is sometimes considered a part of Verschärfung, but I'm placing it here because it must necessarily occur contemporaneously with the iu → ju change above. More specifically, there are a small number of words which begin with the sequence ⟨jiu-⟩, and this sequence as a whole becomes ⟨gju-⟩.

| j | → | ɣ | / | # ___ iu |

“j becomes ɣ before iu when word-initial.”

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jehwlą /ˈjexʷ.lɑ̃/ |

jiul /jiu̯l/ |

jiul /jiu̯l/ |

gyjul /ɣjul/ |

gžjul /gʒjul/ |

ǧul /ʤul/ |

‘Yule’ |

| jeukaną /ˈjeukɑnɑ͂/ |

jiukan /ˈjiu̯kɑn/ |

jiukan /ˈjiu̯kɑn/ |

gyjukan /ˈɣjukɑn/ |

gžjukn /gʒjukn̩/ |

ǧukna /ʤuknɑ/ |

‘to conquer’ |

| wesilōną /ˈwesiloːnɑ͂/ |

iusilōn /ˈiu̯siloːn/ |

jiusilōn /ˈjiu̯siloːn/ |

gyjusiloun /ˈɣjusiloːn/ |

gžjusilon /ˈgʒjusilon/ |

ǧusilan /ˈʤusilɑn/ |

‘to improve’ |

Rhotacism Launch

The phoneme /z/ begins the same process towards rhotacism seen in the other Germanic languages. This change occurs in all environments.

| z | → | ʐ |

“z becomes ʐ in all environments.”

E.g.:

| P.Gmc. | Gothic | Griut. | O.Val. | M.Val. | Valth. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dagaz /ˈdɑɣɑz/ |

dags /dɑxs/ |

dags /dɑɣz/ |

dagz /dɑɡʐ/ |

dagž /dɑɡʒ/ |

daǧ /daʤ/ |

‘day’ |

| hwazuhw /ˈxʷɑzux/ |

ƕazuh /ˈʍɑzuh/ |

hwazuh /ˈxwɑzux/ |

hvazuh /ˈxwɑʐux/ |

hwažū /ˈxwɑʒuː/ |

hwažu /ˈxwɑʒu/ |

‘each’ |

| marzijaną /ˈmɑrzijɑnɑ͂/ |

marzjan /ˈmɑrzjɑn/ |

marzjan /ˈmɑrzjɑn/ |

merzjan /ˈmerʐjɑn/ |

mežjen /ˈmeʒjən/ |

mežin /ˈmeʒin/ |

‘to offend’ |

Expansion of East Germanic Verschärfung

There are actually several changes which occurred at different time periods which have been assembled here under the banner of “Verschärfung”. All of these changes deal with the way glide consonants change in intervocalic environments between the Gothic and Old Valthungian Periods.

Change of /w/ to /wg/

| w | → | wg | / | V | ___ | V | |||

-str

|

Change of /j/ to /gj/

| j | → | ʝj | / | V | ___ | V | |||

-str

|

Change of /h/ to /gw/

| h | → | gw | / | V | ___ | V | |||

-str

|

Change of /hw/ to /gw/

(Much later...)

| hw | → | gw | / | a(ː) | ___ | V | |||

-str

|

Breaking of Long Diphthongs

The “long diphthongs” which can be the result of Verschärfung undergo breaking and the two vowels are separated by a glide: /w/ if the first vowel is +bck and /j/ if the first vowel is -bck.

| V̄V | → | V̄ | { j,w } | V |

Deletion of Final Unstressed /a/

Unstressed word-final a is deleted after m, n, and t; however, it is retained by analogy in inflections, such as the ending of the first person singular present indicative, or the dative singular of many masculine and neuter nouns. Ultimately, this mainly leads to the shortening of some prepositions and change of the neuter -ata ending to -at.

| a | → | Ø | / | C | or t } | ___ # | |||

+nas

|

“Unstressed a is deleted word-finally after a nasal consonant or t.”

Phonology of Old Valthungian ca. 950ad

Vowels

| Short Vowels | Long Vowels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Front | Back | ||

| Close | i · eu [i · y] |

u [u] |

ij · euv [iː · yː] |

uv [uː] | |

| Mid-Close | · y[3] [ʏ] |

ei · eou [eː · øː] |

ou [oː][4] | ||

| Mid-Open | e · eo [ɛ · œ] |

o [ɔ] |

ae · eao [ɛː · œː] |

ao [ɔː] | |

| Open | a [ɑ] |

aa [ɑː] | |||

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Dorsal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p · b [p~pʰ · b] |

t · d [t~tʰ · d] |

k · g [k~kʰ · g] | ||

| Nasal | · m [m] |

· n [n] |

· n[5] [ŋ] | ||

| Fricative | f · bv [ɸ · β] |

ð · þ [ð · θ] |

s · z [s · ʐ] |

h · gy [h · ɣ] | |

| Approximant | · v [w] |

· l [l̪~ɫ] |

· r [r~ɾ] |

· j [j] |

Orthography of Old Valthungian

There is very little extant text in Old Valthungian, and what does exist is quite variable, but this is a “regularlised” version of the orthography used at the time around 850ad, with notes where there are variants.

| Griutungi | IPA | Old Val. | Roman. | Variants | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | ɑ | a | arms ‘poor’ gaf ‘gave’ anþar ‘second’ |

|||

| ā | ɑː | aa | a, ā | haahs ‘shark’ faahan ‘to capture’ andaþaaht ‘rational’ |

Long vowels were sometimes indicated by doubling, sometimes with a macron or any of a half dozen other markings, or ignored completely. | |

| ǣ | ɛː | ae | ai, ee | braeþ ‘wide’ aeðij ‘mother’ twae ‘two’ |

||

| ǭ | ɔː | ao | au, oa, oo, ō | aogyou ‘eye’ fraos ‘happy’ naohuhþan ‘still, yet’ |

||

| b | b | b | barðou ‘axe’ krahba ‘crab’ kalb ‘calf’ |

|||

| b | β~v | bv | vv | silbva ‘self’ arbvi ‘inheritance’ hlaebva ‘bread.dat’ |

||

| g | ɡ | g | gibvan ‘to give’ gardz ‘yard’ dagz ‘day’ |

|||

| g | ɣ | gy | y, gð | aogyou ‘eye’ bagyms ‘tree’ igyil ‘hedgehog’ |

||

| d | d | d | dagz ‘day’ ahdi ‘egg’ word ‘word’ |

|||

| d | ð | ð | dv, dd, δ | aeðij ‘mother’ dalaða ‘down’ þjuðij ‘meaning’ |

Though ð is used here for transcription, a letter derived from the Gothic letter dags (but resembling ϫ, the Coptic gangia) was more often used. | |

| e | ɛ | e | ai | erða ‘earth’ merij ‘sea’ setjan ‘to set’ |

||

| - | œː | eao | eoa, eō, eoo | eaoðijs ‘desert’ feaodjan ‘to feed’ heaohij ‘height’ |

This was used for the umlauted form of ao (Griutungi ǭ, Gothic au). | |

| ē | eː~ei̯ | ei | ē, ee, ej | meina ‘moon’ eimaeti ‘ant’ swei ‘such, thus’ |

||

| - | œ | eo | oe, ø | weorkjan ‘to work’ eorkjus ‘jug’ deohtrjus ‘daughters’ |

This was used for the umlauted form of o (Griutungi o, Gothic au). | |

| - | øː~øu̯ | eou | eoo, eō, ooe | afmeouðij ‘disagreement’ meougyjis ‘girls’ deoumjan ‘to judge’ |

This was used for the umlauted form of oo (Griutungi and Gothic ō). | |

| - | y | eu | y, ue | feutlijns ‘fulfillment’ syndij ‘health’ ynkja ‘ounce’ |

This was used for the umlauted form of u. | |

| - | yː | euv | yy, uue, euu, eeu | heuvhjan ‘to hoard’ seuvtijs ‘gentle’ leuvkjan ‘to latch’ |

This was used for the umlauted form of uv (Griutungi and Gothic ū). | |

| kw | kʷ~kw | qv | kv, q, ku, cv, cu | qvernu ‘mill’ inqvis ‘to you both’ riqviza ‘darker’ |

||

| z | ʐ | z | ȥ | þizae ‘to that’ hwizazij ‘whatever’ izous ‘hers’ |

||

| h | h~x | h | hertou ‘heart’ tehun ‘ten’ fah ‘glad’ |

|||

| þ | θ | þ | th, fh, c[6] | þjuþ ‘people’ frijaþvou ‘love’ ljugvaþ ‘light’ |

From the Gothic 𐌸, this letter represented [θ] in Old Valthungian as it did in Gothic, but became [v] and was replaced by | |

| i | i | i | igyil ‘hedgehog’ izae ‘to her’ þjugi ‘maid’ |

|||

| ī | iː~ij | ij | ī, ei, ij | ijs ‘ice’ ija ‘her’ djupij ‘depth’ |

Late in the Old Valthungian period there was a vowel lengthening of /i/ before /j/ (i.e. /ij/ > /iːj/), but this is not reflected in the Old Valthungian orthography, since the typical depiction of /iː/ was as | |

| j | j | j | i | jeir ‘year’ begjoths ‘both’ jungz ‘young’ |

After i and before u, j was written as | |

| iu | ju | ju | iu, iv, jv | jup ‘up’ knju ‘knee’ þjufs ‘thief’ |

||

| k | k | k | c | korts ‘short’ taekors ‘brother-in-law’ mask ‘mesh, grid’ |

Sometimes written as kh or ch when aspirated. | |

| l | l~ɫ̩ | l | langz ‘long’ silðalijks ‘amazing’ tagl ‘tail’ |

(Syllabic and non-syllabic sonorants were not differentiated in Old Valthungian.) | ||

| m | m~m̩ | m | maeðms ‘gift’ mikils ‘great’ ogvuma ‘primary’ |

(Syllabic and non-syllabic sonorants were not differentiated in Old Valthungian.) | ||

| n | n~n̩ | n | naoþs ‘need’ njuntehun ‘nineteen’ niman ‘to take’ |

(Syllabic and non-syllabic sonorants were not differentiated in Old Valthungian.) | ||

| ng | ŋɡ | ng | gg | singvan ‘to sing’ gangan ‘to go’ wingz ‘wing’ |

Sometimes written with g instead of n in a reflection of the Gothic. | |

| nk | ŋk | nk | gk, gc | drinkan ‘to drink’ anke ‘lower leg’ unkis ‘to us’ |

Sometimes written with g instead of n in a reflection of the Gothic. | |

| nkw | ŋkw | nqv | gq, gqv, nq, nkv, ncu... | inqvar ‘your’ hrinkvan ‘to gather’ sankvus ‘sunset’ |

Sometimes written with g instead of n in a reflection of the Gothic. | |

| o | ɔ | o | au | ortigardz ‘garden’ ogvuma ‘chief’ worms ‘worm’ |

||

| ō | oː~ou̯ | ou | oo, ō, o, ov | ous ‘river-mouth’ sougila ‘sun’ tou ‘to, toward’ |

||

| p | p | p | paeða ‘shirt’ porpora ‘purple’ sleipan ‘to sleep’ |

Sometimes written as ph when aspirated. | ||

| r | r~r̩ | r | riqvus ‘dark’ brouðr ‘brother’ wer ‘man’ |

(Syllabic and non-syllabic sonorants were not differentiated in Old Valthungian.) | ||

| s | s | s | sougila ‘sun’ sehstigjus ‘sixty’ suvs ‘sow’ |

|||

| t | t | t | tungl ‘star’ stjugiti ‘patience’ trjugijnat ‘wooden’ |

Sometimes written as th when aspirated. | ||

| u | u | u | ulbvandus ‘rhinocerus’ ubvils ‘evil’ unþ ‘until’ |

|||

| ū | uː | uv | ū, u, uu | uvhtvou ‘pre-dawn’ þuvsundi ‘thousand’ huvs ‘house’ |

||

| f | ɸ~f | f | fimf ‘five’ svumfsl ‘’ hlaef ‘bread’ |

|||

| w | w | v | vv, uu, ƿ | vilðijs ‘wild’ saliþva ‘guest room’ svei ‘as though’ |

||

| ÿ | ʏ | y | y, i, u, ui | synagovgei ‘synagogue’ hyhsopus ‘hyssop’ þymjam ‘incense’ |

It is likely that this was still a separate phoneme in Old Valthungian from the umlaut of u, though some of the means of transcription overlapped a bit. This phoneme was used only in borrowings from the Greek, and after the Old Valthungian period, these two phonemes had completely merged. Our intermediate transcription shows ÿ for the letter representing Gothic 𐍅/w from Greek υ. The exact pronunciation is unknown, but it seems likely that it was differentiated from eu (the i-umlaut of /u/) in Old Valthungian. These two sounds had merged by the Middle Valthungian period. | |

| kh | kʰ | x | kh, ch, x, χ | Xristus ‘Christ’ ewxaristja ‘eucharist’ katexijns ‘remembrance’ |

This Greek borrowing, which was incorporated into the Gothic alphabet as 𐍇, had merged phonologically with k by the Old Valthungian period, but was occasionally still emphasized with h or even with the Greek letter χ in positions which were not naturally aspirated. Indeed, h was sometimes added to segments which were naturally aspirated, as also happened with p and t. | |

| hw | xw | hv | hv, hw, chv, hu | hvilftri ‘curve’ sehvan ‘to see’ neihv ‘near’ |

The Old Valthungian letter most commonly written as |

An Old Valthungian Text

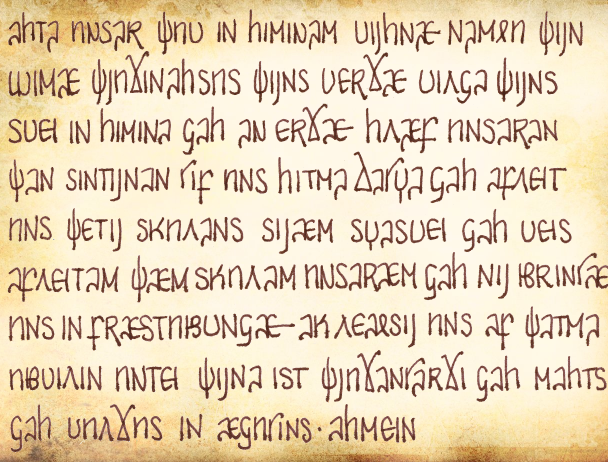

Though there are very few extant Old Valthungian texts, obnoxiously large numbers of the Pater Noster text have been discovered. Here's one now:

ahta unsar þuv in himinam vijhnae namou þijn qvimae þjuðinahsus þijns verðae vilja þijns svei in himina jah an erðae hlaef unsaran þan sintijnan gif uns hitma dagya jah afleit uns þetij skulans sijaem svasvei jah vijs afleitam þaem skulam unsaraem jah nij bringae[s] uns in fraestubvnjae ak leaosij uns af þatma ubvilin untei þijna ist þjuðangarði jah mahts jah vulðus in aejugins · ahmein

.

- ^ The Gothic reflex of East Germanic Glide Insertion applies only when directly adjacent to a high front vowel; hence it applies to saijiþ (before /i/) but not saian (before /ɑ/).

- ^ It is likely that h was actually included in this change, as evidenced by certain changes in the Expansion of East Germanic Verschärfung, but that makes our formula more complicated and really doesn't change the outcome in any measurable way.

- ^ This was likely a lax near-close vowel, not a mid-close vowel; i.e. [ʏ], not [ø]. It later merged with /y/.

- ^ All of the mid-close long vowels may have been diphthongs, though the spelling is likely related to conventions borrowed from early Romance languages of the time rather than an indication of dipthongisation.

- ^ Before g or k

- ^ c for /θ/ is anomalous, only appearing in one extant instance, and is most likely the result of a transcription error, though many have used it (grossly incorrectly) to associate Old Valthungian with the Iberian Goths, positing that this somehow relates to ceceo in modern Spanish. It absolutely does not, and the Old Valthungian speakers never came within 500 miles of present-day Spain, but facts have never stood in the way of good speculation.