Natalician: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| (313 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Tinarian languages]] | |||

{{privatelang}} | {{privatelang}} | ||

{{construction}} | {{construction}} | ||

{{Infobox language | {{Infobox language | ||

|image = | |image = Natalician_Flag_Updated.png | ||

|imagesize = 185px | |imagesize = 185px | ||

|imagecaption = Flag of the Natalician Republic | |imagecaption = Flag of the Natalician Republic | ||

|name = Natalician | |name = Natalician | ||

|nativename = | |nativename = Natal retti | ||

|pronunciation = na. | |pronunciation = na.tal re.tːi | ||

|pronunciation_key = IPA for Natalician | |||

|states = Natalicia; Firenia and the Kontamchian Islands | |states = Natalicia; Firenia and the Kontamchian Islands | ||

|setting = Hazerworld | |||

|region = Central-East Tinaria | |region = Central-East Tinaria | ||

|speakers = | |speakers = 37,123,487 | ||

|date = 2021 | |date = 2021 | ||

|created = | |created = 2021 | ||

|familycolor = Tinarian | |familycolor = Tinarian | ||

|fam2 = Kasenian | |fam2 = Kasenian | ||

|fam3 = | |fam3 = Natalo-Kesperic | ||

|fam4 = | |fam4 = High Kesperic | ||

|fam5 = Old Natalician | |fam5 = Old Natalician | ||

|dia1 = Celician Natalician (''Selis Natal'') | |||

|dia2 = Northern Natalician (''Köpreli Natal'') | |||

|dia3 = Firenic Natalician (''Firen Natal'') | |||

|stand1 = Standard Central Natalician (''Durgum Raskaznol Natal'') | |||

|creator = User:Hazer | |creator = User:Hazer | ||

|script1 = | |script1 = Latin | ||

|minority = Espidon | |official = Natalicia, Firenia, Budernie, Nirania, Kannamie | ||

|minority = Espidon, Amarania (Dogostania) | |||

|nation = Natalicia | |||

|agency = The Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics | |agency = The Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics | ||

|map = Natalician_Distr_Map.png | |map = Natalician_Distr_Map.png | ||

| Line 27: | Line 36: | ||

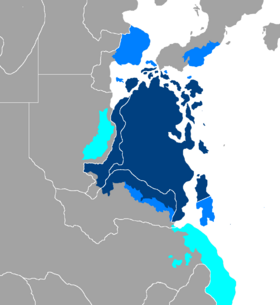

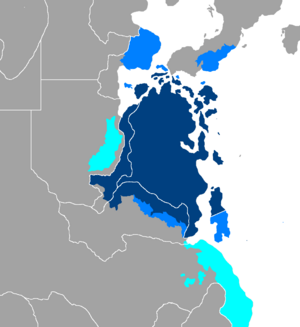

|mapcaption = A map showing the distribution of (native and non-native) speakers of Natalician in Tinaria. Dark blue is native, light blue is secondary language speaker, and cyan is minorities. | |mapcaption = A map showing the distribution of (native and non-native) speakers of Natalician in Tinaria. Dark blue is native, light blue is secondary language speaker, and cyan is minorities. | ||

|notice = IPA | |notice = IPA | ||

|ethnicity = | |ethnicity = Natalese | ||

|ancestor = Old Natalician | |||

}} | }} | ||

'''Natalician''' ({{IPA|/nəˈtɑlɪʃən | '''Natalician''' ({{IPA|/nəˈtɑlɪʃən/}}; [[w:Endonym|endonym]]: ''Natal'' {{IPA|[na.tal]}} or ''Natal Rettive'' {{IPA|/na.tal re.tːive/}}) is a North Kasenian language predominantly spoken in Central East Tinaria, specifically in Natalicia, Firenia, and North-East Nirania. Beyond Natalicia, it holds official status in Budernie, Nirania, and Kannamie, and is recognized as a minority language in East Espidon and within the Dogostanian community in Eastern Amarania. Natalician shares a close linguistic relationship with other North Kasenian languages, such as Espidan and Niranian. | ||

Modern Natalician | Modern Natalician evolved from Old Natalician, which itself descended from an extinct, unnamed language spoken by the Natalo-Kesperian tribes. Today, Natalician stands as one of the world's most significant languages, boasting the highest number of speakers among the Kasenian languages, both as a native and a second language. Approximately 65 million people worldwide speak Natalician, including 37 million native speakers. | ||

Natalician is characterised by its lack of [[w:Grammatical case|grammatical cases]], absence of [[w:Grammatical genders|grammatical genders]], minimal irregularity, and a systematic grammar. Its orthography is straightforward, devoid of digraphs, diphthongs, or similar complexities, making it an accessible language to read and learn. | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

The | The earliest traces of the Natalician language date back to the year 334, featuring a vocabulary and grammar markedly different from its modern descendant. The history of the Natalician language is divided into three distinct periods: '''Classic Natalician''' (334–1203), '''Old Natalician''' (1203–1540), and '''Modern Natalician''' (1540–present). As of 2021, the language is estimated to be 1,687 years old. | ||

The | |||

===Classic Natalician=== | |||

Also known as '''Poetic Natalician''' or the '''Natalo-Kesperian Language''', the earliest traces of this language are found solely in ancient poetry and inscriptions on recovered artifacts. However, the NACL (Natalician Academy of Classical Languages) considers these remnants insufficient to be deemed a complete or valid representation of the spoken Natalo-Kesperian language, largely due to the dominance of illiteracy in the pre-Killistic era and the overly formal nature of the vocabulary used in these writings. | |||

Classic Natalician's vocabulary contains numerous direct elements from the early Proto-North-Kasenian language, which eventually faded during the migratory era. This decline was influenced by cultural clashes and the increasing incorporation of loanwords. | |||

Unfortunately, no documents from the Classic Natalician period have survived. Consequently, there is no known evidence detailing the development of the language during this primary era. | |||

=== | ===Old Natalician=== | ||

{{Quote box |align=right|quoted=true | | {{Quote box |align=right|quoted=true | | ||

|salign=right | |salign=right | ||

|quote='' | |quote=''Reširi ägsös nör på tånåka if kelševi wez̊en fölsi sös.'' <br /> “The people have the right to write and say what they please.” | ||

|source= | |source= The first quote from the famous Ulun Cilesli Irkete's 1210 language guide | ||

}} | }} | ||

With the dawn of the Killistic era, the Natalese tribes gained access to invaluable knowledge, brought by the ascension of their proclaimed king, '''Ribel Zömeri'''. This period marked a significant rise in literacy rates within the nascent and unified Natalese monarchy, which spanned from 1203 to 1834. During this era, the Natalician language saw its first instances of written records and experienced a flourishing of printed works. | |||

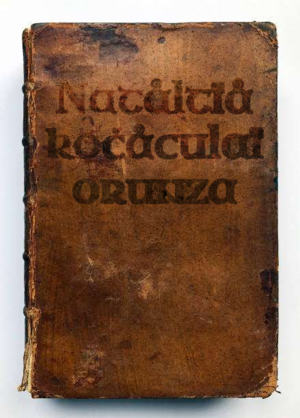

The earliest known book containing written evidence of the Natalician language is titled "Natåltïå kočåculaï orūnza" (Natalician Guide Book). This seminal work was authored and published by the late Ulun Cilesli Irkete in the year 1210. Subsequently, numerous documents have been preserved through generations and are now treasured artifacts housed in the '''Natalician Grand Museum of Literature and Artifacts''' in Celicia. | |||

[[file:Old_natalician_book.png|thumb|A recovered old copy of Prof. Irkete's Old Natalician guide book]] | |||

Many historians and literary scholars have debated the relationship between Classic and Old Natalician, with some arguing that they are identical. However, the scarcity of evidence has left these claims unresolved. Scholar '''Iček Friktinäm''' posits: ''"Old Natalician may be the result of the incorporation of new local loanwords, and the diverse dialects might have led to deviations from the Kasenian roots of the standard spoken Natalician of that time."'' | |||

Old Natalician is characterized by significantly different grammar and vocabulary compared to modern Natalician. The most notable differences include the presence of ''vowel harmony'' and ''grammatical cases''. The language featured four types of vowel harmony and three grammatical cases: '''Nominative''', '''Accusative''', and '''Genitive'''. Additionally, distinct suffixes and verb conjugations highlight the major grammatical differences. | |||

===Modern Natalician=== | |||

{{Quote box |align=right|quoted=true | | |||

|salign=right | |||

|quote=''Ťenałr tanakavsai der garla. Ťenałr nameš tanakavsai der ünete.'' <br /> “History is written by the victor. Our history is written by the people.” | |||

|source= Zafel Sörät Fortla, founder of the republic | |||

}} | |||

The Natalician language has been continuously evolving since the 15th century with the decline of the monarchy and the rise of '''Goz Hoz''' to power the next few centuries. Trades and exchanges between nations has allowed for a path to new loanwords added to the Natalician lexicon. This evolution continued until the establishment of the Republic in 1845 by '''Zafel Sörät Fortla''', when the "Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics" was created and assumed responsibility for tracking the language's development. | |||

==Etymology== | |||

The name Natalicia, the Natalese and the Natalician language, originates from the '''Natala''' tribes of the Natalo-Kesperian community in central east Tinaria. The term derives from the Proto-Kasenian word '''Nåťåla''', meaning "fairness." This evolved into ''Nåsåla'' in Old Natalician and eventually became ''Nasala'' in Modern Natalician. | |||

== | ==Geographical Distribution== | ||

[[file:Natalician_Distr_Map.png|thumb|Geographical distribution of speakers of the Natalician language in the Natal Koman area]] | |||

Natalician is spoken in the Natalician republic, the kingdom of Firenia, the northwestern camps of the Nirenian republic and as a minority language in Espidon and Amarania. The popularity of Natalician has increased following the Natalician Dispora program, resulting in an increase of demand for the language to be taught as a foreign language in most of Tinaria and the other three continents. | |||

An exact global number of Natalician speakers is a matter of difference due to the several varieties of Natalician status as separate "languages" or "dialects" is disputed for political and linguistic reasons, including certain forms of Kasperian and Rufeic Natalician. With the inclusion or exclusion of said varieties, the estimate is approximately 40 million people who speak Natalician as a first language, 5 to 15 million speak it as a second language, and 40 to 50 million as a foreign language. This would imply approximately 85 to 105 million Natalician speakers worldwide. | |||

Natalician sociolinguist Mezred Siförtah estimated a number of 150 million Natalician foreign language speakers without clarifying the criteria by which he classified a speaker. | |||

=== Tinaria === | |||

As of 2024, about 40 million people, or 12% of the Tinarian Union's population, spoke Natalician as their mother tongue, making it the fourth-most widely spoken language on the continent after English, Secaltan and Amaranian, the fourth biggest language in terms of overall speakers, as well as the third most spoken native language. | |||

===Natal Koman=== | |||

The area in central east Tinaria where the majority of the population speaks Natalician as a first or second language and has Natalician as a (co-)official language is called the "''Natal Koman'' (Natalician for: 'Natalese World')". Natalician is the official or co-official language of the following countries: | |||

* Natalicia (official) | |||

* Firenia (official) | |||

* The Kontamchian Islands (official) | |||

* Søfrøzkev, Niččišey and Vørkek regions of Nirenia (co-official) | |||

* Province of Trumuyet of Tuggol (co-official) | |||

* The Islands of Kannamay, Binjes and Vurvuda (co-official) | |||

=== | ===Outside the Natal Koman=== | ||

Natalician is a recognised minority language in the following countries: | |||

* Espidon (in the provinces of Zafur and Iktišek) | |||

* East of the Federal Dogostanian Republic in Amarania | |||

== Phonology == | |||

=== Consonants === | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

|+ Consonant phonemes of Standard | |+ Consonant phonemes of Standard Natalician | ||

! colspan=2 rowspan=2 | | ! colspan=2 rowspan=2 | | ||

! rowspan=2| [[w:Labial consonant|Labial]] | ! rowspan=2| [[w:Labial consonant|Labial]] | ||

| Line 471: | Line 132: | ||

| n | | n | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 484: | Line 145: | ||

| | | | ||

| k | | k | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 494: | Line 155: | ||

| | | | ||

| ɡ | | ɡ | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 503: | Line 164: | ||

| s θ | | s θ | ||

| ʃ | | ʃ | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 511: | Line 172: | ||

! {{small|[[w:voice (phonetics)|voiced]]}} | ! {{small|[[w:voice (phonetics)|voiced]]}} | ||

| v | | v | ||

| z | | z ð | ||

| ʒ | | ʒ | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 520: | Line 181: | ||

!rowspan=2| [[w:Affricate consonant|Affricate]] | !rowspan=2| [[w:Affricate consonant|Affricate]] | ||

! {{small|[[w:voicelessness|voiceless]]}} | ! {{small|[[w:voicelessness|voiceless]]}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| t͡ʃ | | t͡ʃ | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 531: | Line 192: | ||

! {{small|[[w:voicelessness|voiceless]]}} | ! {{small|[[w:voicelessness|voiceless]]}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| d͡ʒ | | d͡ʒ | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 538: | Line 199: | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

!rowspan= | !rowspan=2| [[w:Approximant consonant|Approximant]] | ||

! {{small|[[w:semivowel|semivowel]]}} | ! {{small|[[w:semivowel|semivowel]]}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 552: | Line 213: | ||

| | | | ||

| l | | l | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|} | |||

# The phoneme /ʒ/ is usually realised as /dʒ/ in many dialects. In the island dialects, it is replaced with /d͡ʒ/ when it occurs word-initially. | |||

# /l/ can undergo delateralisation in most dialects if preceeded by /i/ - for example, ''senil'' ("problem") is pronounced /se.nij/ rather than /se.nil/. | |||

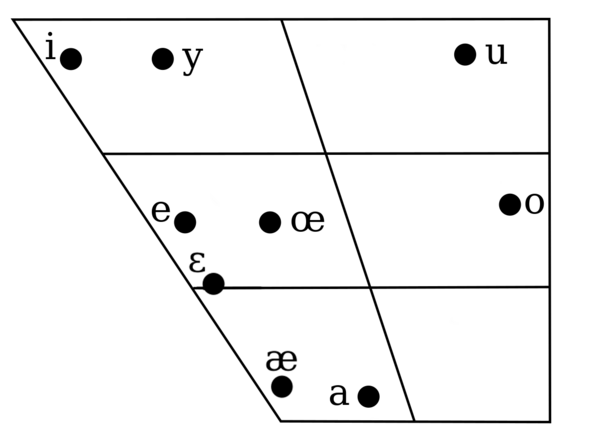

===Vowels=== | |||

[[file:Natalician_vh_chart.png|border|600px]] | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" | |||

|+ Vowel phonemes of standard Natalician | |||

! rowspan="2" | | |||

! colspan="2" | [[Front vowel|Front]] | |||

! colspan="2" | [[Back vowel|Back]] | |||

|- | |||

! {{small|unrounded}} | |||

! {{small|rounded}} | |||

! {{small|unrounded}} | |||

! {{small|rounded}} | |||

|- | |||

! [[Close vowel|Close]] | |||

| i | |||

| y | |||

| | |||

| u | |||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! Near-open | ||

| | | æ | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! [[Open vowel|Open]] | ||

| e | |||

| œ | |||

| a | |||

| o | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|} | |} | ||

The vowels of the Natalician language are, in their alphabetical order, {{angbr|a}}, {{angbr|ä}}, {{angbr|e}}, {{angbr|i}}, {{angbr|o}}, {{angbr|ö}}, {{angbr|u}}, {{angbr|ü}}. | |||

The Natalician vowel system can be considered as being three-dimensional, where vowels are characterised by how and where they are articulated focusing on three key features: [[Vowel#Backness|front and back]], rounded and unrounded and [[Vowel#Height|vowel height]]. | |||

'''NOTE:''' | |||

When the vowels /i/, /u/ precede or succeed another vowel, they become /j/, /w/ respectively. If both vowels meet one another, only the /i/ will transform into a /j/ while the /u/ remains unchanged. | |||

==Orthography== | |||

===Alphabet=== | |||

Natalician has a straightforward orthography, meaning regular spelling with (almost) no diphthong or digraph or anything of the sort. In linguistic terms, the writing system is a phonemic orthography. | |||

====Standard Natalician alphabet==== | |||

[[File:Natalician_qwerty.png|thumb|A Natalician QWERTY computer keyboard layout.]] | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | |||

! Letter !! Name !! [[w:International Phonetic Alphabet|IPA]] | |||

|+ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:A|Aa]] || a [a] || /a/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:Ä|Ää]] || ä [æ] || /æ/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:B|Bb]] || be [be] || /b/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:C|Cc]] || ce [d͡ʒe] || /d͡ʒ/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:Č|Čč]] || če [t͡ʃe] || /t͡ʃ/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:D|Dd]] || de [de] || /d/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:Ď|Ďď]] || ďe [ðe] || /ð/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:E|Ee]] || e [e] || /ɛ/, /e/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:F|Ff]] || ef [ɛf] || /f/ | |||

|- | |||

[[ | | [[w:G|Gg]] || ge [ɡ] || /g/ | ||

|- | |||

| [[w:H|Hh]] || ha [ha] || /h/, /j/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:I|Ii]] || i [i] || /i/, /j/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:J|Jj]] || je [ʒe] || /ʒ/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:K|Kk]] || ka [ka] || /k/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:L|Ll]] || el [ɛl] || /l/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:Ł|Łł]] || girbit el [gir.bit ɛl] || /ː/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:M|Mm]] || em [ɛm] || /m/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:N|Nn]] || en [ɛn] || /n/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:O|Oo]] || o [o] || /o/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:Ö|Öö]] || ö [œ] || /œ/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:P|Pp]] || pe [pe] || /p/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:R|Rr]] || er [ɛr] || /r/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:Ř|Řř]] || eř [ɛʁ] || /ʁ/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:S|Ss]] || es [s] || /s/ | |||

|- | |||

| [[w:Š|Šš]] || eš [ɛʃ] || /ʃ/ | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | [[w:T|Tt]] || te [te] || /t/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[w:Ť|Ťť]] || ťe [θe] || /θ/ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| [[w:U|Uu]] || u [u] || /u/ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| [[w:Ü|Üü]] || ü [y] || /y/ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | [[w:V|Vv]] || ve [ve] || /v/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[w:W|Ww]] || wa [wa] || /w/ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| [[w:Z|Zz]] || ze [ze] || /z/ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

* The letter that is called ''Girbit El'' ("Silent L"), written {{angbr|Ł}} in Natalician orthography, represents vowel lengthening. It never occurs at the beginning of a word or a syllable, always follows a vowel and always preceeds a consonant. The vowel that preceeds it is lengthened. | |||

* The letter {{angbr|H}} in Natalician orthography represents two sounds: The /h/ sound, and the /j/ sound. If the letter {{angbr|H}} is located at the beginning of the (non-compound) word, it takes the /h/ sound, otherwise it takes the /j/ sound. (e.g. ''Hiloh'' /hi.loj/'' "Hello", ''Konah /ko.naj/'' "Beautiful", ''Haz /haz/ "This") | |||

==Grammar== | |||

===Consonant harmony=== | |||

Natalician orthography reflects voice sandhi voicing, a form of consonant mutation with two consonants that meet, and the second is voiced and the first is unvoiced. The first unvoiced consonant {{IPA|[p t f ʃ t͡ʃ θ k s]}} is voiced to {{IPA|[b d v ʒ d͡ʒ ð ɡ z]}}, but the orthography remains unchanged. | |||

* ''Kütdüs'' (you drink) realises the /t/ as a /d/ due to the voiced consonant that follows; hence, it becomes /kydː.ys/. | |||

* ''Äzäpzik'' (announcement) realises the /p/ as a /b/; hence, it becomes /æ.zæb.zik/. | |||

'''NOTE:''' The only time a voiced consonant gets devoiced is when the voiced-voiceless pairs meet and the voiced consonant preceeds the voiceless one, resulting in a gemination of the voiceless consonant: ''Lüzševi'' /lyʃː.e.vi/ - ''Özse'' /œsː.e/ - ''Kodtos'' /kotːos/ | |||

===== | === Vowel harmony === | ||

===== | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin-left: 1em" | ||

! rowspan="2" | Natalician Vowel Harmony | |||

! colspan="5" | Front Vowels || colspan="3" | Back Vowels | |||

|- | |||

! colspan="3" | Unrounded || colspan="2" | Rounded || colspan="1" | Unrounded || colspan="2" | Rounded | |||

|- | |||

! Vowel | |||

| style="border-right: 0;" | '''ä''' || '''e''' || '''i''' || '''ö''' | |||

| style="border-left: 0;" | '''ü''' || '''a''' || '''o''' | |||

| style="border-left: 0;" | '''u''' | |||

|- style="text-align: center;" | |||

! Type Ĭ (Backness + Rounding) | |||

| colspan="3" | '''i''' || colspan="2" | '''ü''' || colspan="1" | '''a''' || colspan="2" | '''u''' | |||

|- | |||

! Type Ĕ (Backness) | |||

| colspan="5" | '''e''' || colspan="5" | '''o''' | |||

|- style="text-align: center;" | |||

|} | |||

====The principle of vowel harmony==== | |||

# If the first vowel of a word is a back vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a back vowel; if the first is a front vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a front vowel. | |||

# If the first vowel is unrounded, so too are subsequent vowels. | |||

The second and third rules minimize muscular effort during speech. More specifically, they are related to the phenomenon of labial assimilation: If the lips are '''rounded''' (a process that requires muscular effort) for the first vowel they may stay rounded for subsequent vowels. If they are '''unrounded''' for the first vowel, the speaker does not make the additional muscular effort to round them subsequently. | |||

Grammatical affixes have "a chameleon-like quality" and obey one of the following patterns of vowel harmony: | |||

The | * '''Twofold ĕ (''-e/-o'')''': The article, for example, is ''-(v)e'' after front vowels and ''-(v)o'' after back vowels. | ||

* '''Fourfold ĭ (''-i/-a/-ü/-u'')''': The verb infinitive suffix, for example, is ''-i'' or ''-a'' after unrounded vowels (front or back respectively); and ''-ü'' or ''-u'' after the corresponding rounded vowels. | |||

* '''Type & 'and'''': The adjectival passive voice suffix, for example, is ''-t&t'', the ''&'' being the same vowel as the previous one. | |||

Practically, the twofold pattern (usually referred to as the type Ĕ) means that in the environment where the vowel in the word stem is formed in the front of the mouth, the suffix will take the '''e''' form, while if it is formed in the back it will take the '''o''' form. The fourfold pattern (also called the type Ĭ) accounts for rounding as well as for front/back. The type & pattern is the reppetition of the same last vowel. | |||

The following examples, based on the verbal noun suffix ''-zĭk'', illustrate the principles of type Ĭ vowel harmony in practice: ''Ährä'''zik''''' ("Swimming"), ''Ok'''zuk''''' ("Knowledge"), ''Ian'''zak''''' ("Eating"), ''Nör'''zük''''' ("Living"). | |||

==== Exceptions to vowel harmony ==== | |||

These are four word-classes that are exceptions to the rules of vowel harmony: | |||

# '''Native, non-compound words''', e.g. ''Ela'' "then", ''Čela'' "drink", ''Ťehozuk'' "discussion" | |||

# '''Native compound words''', e.g. ''Pave'' "for what" | |||

# '''Foreign words''', e.g. many English loanwords such as '''Sertifikäht''' (certificate), '''Hospitol''' (hospital), '''Kompiułter''' (computer) | |||

# '''Invariable prefixes / suffixes:''' | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | |||

! scope="col" | Invariable prefix or suffix | |||

! scope="col" | Natalician example | |||

! scope="col" | Meaning in English | |||

! scope="col" | Remarks | |||

|- | |||

| '''–(v)iš''' | |||

| ''üčiš'' || "exit" | |||

| From ''üč'' "leave" | |||

|- | |||

| '''öz-''' | |||

| ''özhaša'' || "to return" | |||

| From ''haša'' "to come" | |||

|- | |||

| '''gel-''' | |||

| ''gelsincetet'' || "decomposed" | |||

| From ''since'' "compose" | |||

|} | |||

==== | ====Note==== | ||

* A native compound does not obey vowel harmony: ''Ras+cezil'' ("city center"—a place name) | |||

* Loanwords also disobeys vowel harmony: ''Kofi'' ("Coffee") | |||

* Every grammatical prefix disobeys the vowel harmony aswell. | |||

===Parts of speech=== | |||

There are nine '''parts of speech''' (''kurzuk felev'') in Natalician. | |||

#'''[[noun]]''' (''iztin'' "name"); | |||

#'''[[pronoun]]''' (''kahuče'' from Amaranian '''kayoûtshéy''', or ''reširnel iztinev'' "personal names"); | |||

#'''[[adjective]]''' (''oruvaš'' "quality"); | |||

#'''[[verb]]''' (''öhker'' from Amaranian '''eiyiker''', or ''dirzik'' "action"); | |||

#'''[[adverb]]''' (''randara''); | |||

#'''[[postposition]]''' (''hasla eř'' "later addition"); | |||

#'''[[Grammatical conjunction|conjunction]]''' (''sedlek übeřre'' "sentence link"); | |||

#'''[[Grammatical particle|particle]]''' (''meres''); | |||

#'''[[interjection]]''' (''venzik rimizli'' "feeling manifester"). | |||

Only nouns and verbs are inflected in Natalician. An adjective can usually be treated as a noun, in which case it can also be inflected. Inflection can give a noun features of a verb such as person and tense. With inflection, a verb can become one of the following: | |||

* '''verbal noun''' (''öhkernel iztin''); | |||

* verbal adjective (''öhkernel oruvaš''); | |||

* '''verbal adverb''' (''öhkernel randara''). | |||

These have peculiarities not shared with other nouns, adjectives or adverbs. | |||

For example, some participles take a ''person'' the way verbs do. | |||

Also, a verbal noun or adverb can take a direct object. | |||

There are two standards for listing verbs in dictionaries. Most dictionaries follow the tradition of spelling out the '''infinitive form''' of the verb as the [[headword]] of the entry, but others such as the Zeraltan Natalician-English Dictionary are more technical and spell out the '''stem''' of the verb instead, that is, they spell out a string of letters that is useful for producing all other verb forms through morphological rules. Similar to the latter, this article follows the stem-as-citeword standard. | |||

* '' | * '''Infinitive''': ''oruvu'' ("to read") | ||

* '' | * '''Stem''': ''oru-'' ("read") | ||

In Natalician, the verbal stem is also the second-person singular imperative form. Example: | |||

:''oru-'' (stem meaning "read") | |||

:''Oru!'' ("Read!") | |||

Many verbs are formed from nouns by addition of ''-še''. For example: | |||

:''mar'' – "structure" | |||

:''maršo'' – "build / construct" | |||

Most adjectives can be treated as nouns or pronouns. For example, ''ďen'' can mean "young", "young person", or "the young person being referred to". | |||

[[Comparison (grammar)|Comparison]] of adjectives is not done by inflecting adjectives or adverbs, but by other means (described [[#Comparison|below]]). | |||

Adjectives can serve as adverbs, sometimes by means of repetition: | |||

:''danah'' – "happy" | |||

:''danah danah'' – "happily" | |||

===Nouns=== | |||

==== | ====Inflection==== | ||

A Natalician noun has no gender. | |||

There are seven regular inflectional affixes in Natalician. | |||

{| class="wikitable | {| class="wikitable" | ||

! | |+Inflectional affixes in English | ||

!Affix | |||

!Grammatical category | |||

!Mark | |||

!Part of speech | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | -(v)ĕv | ||

|Grammatical number|Number | |||

|plural | |||

|nouns | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | -'(ĭ)n | ||

|Case | |||

|genitive | |||

|nouns and noun phrases, pronouns | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | -tĕs | ||

|Aspect | |||

|progressive | |||

|gerunds or participles | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | -t&t | ||

|[[Grammatical tense|Tense]] | |||

|[[Past tense|past]] ([[Simple aspect|simple]]) | |||

|[[verb]]s | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | -(ĕ)m | ||

|[[Degree of comparison]] | |||

|[[comparative]] | |||

|[[adjective]]s and [[adverbs]] | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | -mĕ | ||

|[[Degree of comparison]] | |||

|[[superlative]] | |||

|[[adjective]]s and [[adverbs]] | |||

|} | |||

Through its presence or absence, the plural ending shows distinctions of [[Grammatical number|number]]. | |||

=====Number===== | |||

A noun is made plural by addition of ''-(v)ev'' or ''-(v)ov'' (depending on the vowel harmony). When a numeral is used with a noun, however, the plural suffix is ''not'' used: | |||

:{| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | ''böšter'' || "table" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | ''böšterev'' || "tables" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | ''nav böšter'' || "four tables" | ||

|} | |||

The plural ending also allows a family (living in one house) to be designated by a single member: | |||

:{| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | ''ičedevev'' || "Ičede and his family / The Ičedes" | ||

|} | |||

====Verbal nouns==== | |||

The '''verbal noun''' is created by the addition of the suffix ''-zĭk'' and the '''root''' of the verb. | |||

:{| class=wikitable | |||

! Verb !! Noun | |||

|- | |||

| ''fas-'' "give" || ''faszak'' "giving / donation" | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | ''den-'' "let" || ''denzik'' "allowance" | ||

|- | |||

| ''kur-'' "speak" || ''kurzuk'' "speech" | |||

|- | |||

| ''dön-'' "ask" || ''dönzük'' "question" | |||

|} | |} | ||

''' | The verb ''et-'' "make, do" can be considered as an '''auxiliary verb''', since for example it is often used with verbal nouns borrowed from other languages, such as Arabic: | ||

''kabul et-'' "accept" (''kabul'' "[an] accepting"); | |||

''reddet-'' "reject" (''ret'' "[a] rejecting"); | |||

''ziyaret et-'' "visit" (''ziyaret'' "[a] visiting"). | |||

Considered as units, these are transitive verbs; but the nouns in them can also, by themselves, take direct objects: | |||

''Antalya'yı ziyaret'' "visit to Antalya". | |||

What looks like an ablative gerund is usually an adverb; the ending ''-meden'' usually has the sense of "without". | |||

See [[#Adverbs]] below. | |||

An infinitive in the absolute case can be the object of a verb such as ''iste-'' "want": | |||

''' | {{interlinear|lang=tr|indent=2 | ||

| Kimi eğitime devam etmek, kimi de çalışmak istiyor. | |||

| some-of-them towards-education continuation make some-of-them also work want | |||

| Some want to continue their education, and some want to work" | |||

(''source:'' ''Cumhuriyet Pazar Dergi'', 14 August 2005, p. 1.)}} | |||

Note here that the compound verb ''devam et-'' "continue, last" does not take a direct object, but is complemented by a dative noun. | |||

{| | Another way to express obligation (besides with ''lâzım'' as in the [[#lazim|earlier example]]) is by means of ''zor'' "trouble, compulsion" and an infinitive: | ||

''Gitmek zoru'' "Go compulsion", | |||

| | ''Gitmek zorundayız'' "We must go". | ||

(''Source:'' same as the last example.) | |||

Both an infinitive and a gerund are objects of the postposition ''için'' "for" in the third sentence of the quotation within the following quotation: | |||

{{Verse translation| | |||

{{lang|tr| | |||

Tesis yetkilileri, | |||

"Bölge insanları genelde tutucu. | |||

Sahil kesimleri | |||

yola yakın olduğu için | |||

rahat bir şekilde göle giremiyorlar. | |||

Biz de | |||

hem yoldan geçenlerin görüş açısını '''kapatmak''' | |||

hem de erkeklerin rahatsız '''etmemesi''' için | |||

paravan kullanıyoruz" | |||

dedi. | |||

Ancak paravanın aralarından | |||

çocukların karşı tarafı gözetlemeleri | |||

engellenemedi. | |||

}} | |||

| | |||

Facility its-authorities | |||

"District its-people in-general conservative. | |||

Shore its-sections | |||

to-road near their-being for | |||

comfortable a in-form to-lake they-cannot-enter. | |||

We also | |||

both from-road of-passers sight their-angle '''to-close''' | |||

and men's uncomfortable '''their-not-making''' for | |||

screen we-are-using" | |||

they-said. | |||

But curtain's from-its-gaps | |||

children's other side their-spying | |||

cannot-be-hindered. | |||

|attr1=''Cumhuriyet,'' 9 August 2005, p. 1.}} | |||

A free translation is: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

The facility authorities said: "The people of this district [namely [[Edremit, Van]]] are generally conservative. They cannot enter [[Lake Van|the lake]] comfortably, because the shore areas are near the road. So we are using a screen, both '''to close off''' the view of passersby on the road, and so '''that''' men '''will not cause discomfort.'''" However, children cannot be prevented from spying on the other side through gaps in the screen. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

===Pronouns=== | |||

{| class=wikitable | |||

|+ Natalician pronouns | |||

|- | |||

! colspan=3 rowspan=2 | !! colspan=2 | personal pronouns | |||

|- | |||

! [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#subject|subjective]] !! [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#object|objective]] | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! rowspan=2 | [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#first person|first<br>person]] !! colspan=2 | singular | ||

| {{term|nei}} || {{term|in}} | |||

|- valign="top" | |||

! colspan=2 valign="middle" | plural | |||

| {{term|namše}} || {{term|nameš}} | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! rowspan=2 | [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#second person|second<br>person]] !! colspan=2 | singular | ||

| {{term|on}} || {{term|un}} | |||

|- valign="top" | |||

! colspan=2 valign="middle" | plural | |||

| {{term|daš}} || {{term|daša}} | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! rowspan=2 | [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#third person|third<br>person]] !! colspan=2 | singular | ||

| {{term|sü}} || {{term|süs}} | |||

|- valign="top" | |||

! colspan=2 valign="middle" | plural | |||

| {{term|so}} || {{term|soz}} | |||

|} | |||

{| class=wikitable | |||

|+ Natalician possessive pronouns | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! colspan=3 rowspan=2 | !! colspan=2 | possessive pronouns | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#subject|possessive determiner]] !! [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#object|possessive pronoun]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! rowspan=2 | [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#first person|first<br>person]] !! colspan=2 | singular | ||

| {{term|in}} || {{term|ini}} | |||

|- valign="top" | |||

! colspan=2 valign="middle" | plural | |||

| {{term|nameš}} || {{term|nameše}} | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! rowspan=2 | [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#second person|second<br>person]] !! colspan=2 | singular | ||

| {{term|un}} || {{term|onu}} | |||

|- valign="top" | |||

! colspan=2 valign="middle" | plural | |||

| {{term|daša}} || {{term|dašo}} | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! rowspan=2 | [[wikt:Appendix:Glossary#third person|third<br>person]] !! colspan=2 | singular | ||

| {{term|süs}} || {{term|süzü}} | |||

|- valign="top" | |||

! colspan=2 valign="middle" | plural | |||

| {{term|soz}} || {{term|sozun}} | |||

|} | |} | ||

The | The possessive determiners are the same as the objective personal pronouns. The possessive pronouns always succeed the subject/object. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ Examples with ''teyze'' ("maternal aunt") | |||

|+ '' | |||

|- | |- | ||

! Example !! Composition !! Translation | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | ''ert in'' || ''ert'' "father" + ''in'' "me" || "my father" | ||

|- | |||

| ''ert daša'' || ''ert'' "father" + ''daša'' "you (plural objective)" || "your father" | |||

|- | |||

| ''ertev süs'' || ''ert'' "father" + ''-ev'' (plural suffix) + ''süs'' "him/her (objective)" || "his/her fathers" | |||

|} | |} | ||

===Verbs=== | |||

====Stems of verbs==== | |||

Many stems in the dictionary are indivisible; others consist of endings attached to a root. | |||

==== | ====Verb-stems from nouns==== | ||

Many verbs are formed from nouns or adjectives with ''-šĕ'': | |||

:{| class="wikitable" | |||

! Noun !! Verb | |||

|- | |||

| ''ergem'' "negativity" || ''ergem'''še'''-'' "negate" | |||

|- | |||

| ''an'' "one" || ''an'''šo'''-'' "unite" | |||

|- | |||

| ''kel'' "word" || ''kel'''še'''-'' "say" | |||

|} | |||

====Voice==== | |||

A verbal root, or a verb-stem in ''-šĕ'', can be lengthened with certain '''extensions'''. If present, they appear in the following order, and they indicate distinctions of '''voice''': | |||

:{|class="wikitable" | |||

|+ Extensions for voice | |||

|- | |||

! Voice !! Ending !! Example | |||

|- | |||

!Reflexive | |||

|''-(ĭ)r'';||kark (wash); karkar ([take a] shower) | |||

|- | |||

!Reciprocal | |||

|''-cĕ'';||dol (send); dolco (exchange) | |||

|- | |||

!Causative | |||

|''-(&)z'';||ian (eat); ianaz (feed) | |||

|- | |||

!Passive | |||

|''-(ĭ)v'';||artan (help); artanav (be helped) | |||

|} | |||

These endings might seem to be ''inflectional'' in the sense of the {{section link||Introduction}} above, but their meanings are not always clear from their particular names, and dictionaries do generally give the resulting forms, so in this sense they are ''constructive'' endings. | |||

The causative extension makes an intransitive verb transitive, and a transitive verb '''factitive'''. Together, the reciprocal and causative extension make the '''repetitive''' extension ''-cĕz''. | |||

:{| class="wikitable" | |||

! Verb Root/Stem !! New Verb !! Voice | |||

|- | |||

| rowspan=2 | ''dol'' "send" | |||

| ''dolco'' "exchange" || ''-co'' (reciprocal) | |||

|- | |||

| ''doluv'' "be sent" || ''-uv'' (passive) | |||

|- | |||

| rowspan=2 | ''ver'' "Fix (something)" | |||

| ''verir'' "fix oneself" || ''-ir'' (reflexive) | |||

|- | |||

| ''verce'' "correct each other" || ''-ce'' (reciprocal) | |||

|- | |||

| ''fäs'' "die" | |||

| ''fäsäz'' "kill" || ''-äz'' (causative) | |||

|- | |||

|''küt'' "drink" | |||

| ''kütde'' "do not drink" || ''-de'' (negative) | |||

|} | |||

===Questions=== | |||

The interrogative particle ''a'' precedes the verb in the interrogative form: | |||

:''A hašzar?'' "Are you coming?" | |||

:''A haštaz?'' "Did you come?" | |||

===Optative mood=== | |||

Usually, in the '''optative''' (''öštüküh''), there is one series of endings to express something wished for: | |||

:{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+ Optative Moods | |||

|- | |||

! Number !! Person !! Ending !! Example !! English Translation | |||

|- | |||

! rowspan=3 | Singular | |||

! 1st | |||

| ''-deriz'' ||''Nörderiz''||"May I live" | |||

|- | |||

! 2nd | |||

| ''-derid'' || ''Nörderid'' ||"May you live" | |||

|- | |||

! 3rd | |||

| ''-deris'' || ''Nörderis''|| "May [her/him/it] live" | |||

|- | |||

! rowspan=3 | Plural | |||

! 1st | |||

| ''-derizis'' || ''Nörderizis'' ||"May we live" | |||

|- | |||

! 2nd | |||

| ''-deridis'' || ''Nörderidis'' ||"May you live" | |||

|- | |||

! 3rd | |||

| ''-derisis''' || ''Nörderisis''||"May they live" | |||

|} | |||

== | ===Compound bases===<!-- This section is linked from [[Grammatical mood]] --> | ||

[[ | |||

*Past tenses: | |||

**'''continuous past:''' ''Entiz hašzai'' or ''Haštazar'' "I was coming"; | |||

**'''aorist past:''' ''Entiz haštaz'' "I used to come"; | |||

**'''future past:''' ''Entiz hašvaz'' "I was going to come"; | |||

**'''necessitative past:''' ''Entiz ekin hašzai'' "I had to come"; | |||

**'''conditional past:''' ''Nu ulan haštaz'' "If only I had come." | |||

*Inferential tenses: | |||

**'''continuous inferential:''' ''Enzei hašlozu'' "It seems (they say) I am coming"; | |||

**'''future inferential:''' ''Ekin hašlovuz'' "It seems I shall come"; | |||

**'''aorist inferential:''' ''Hašlozu'' "It seems I come"; | |||

**'''necessitative inferential:''' ''Ekin hašlozu'' "They say I must come." | |||

=== | =Vocabulary= | ||

===Phrasebook=== | |||

Natalician common words and phrases useful for learners. | |||

''' | {| | ||

|- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | |||

{| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" style="text-align: center;" | |||

| | |+ '''Communication''' | ||

| | ! colspan="3"|Phrasebook 1 | ||

| | |- | ||

! width="33%"|Natalician | |||

! width="33%"|English | |||

! width="33%"|IPA | |||

|- | |||

| Hiloh <br> Sohon || Hello || [[IPA for Natalician#Standard_Natalician|[hi.loj]]] <br> [[IPA for Natalician#Standard_Natalician|[so.jon]]] | |||

|- | |||

Luthic | | Čikel anda || Good day || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃi.kɛl an.da]]] | ||

|- | |||

| Čikel sehan || Good morning || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃi.kɛl se.jan]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Čikel kehan || Good afternoon || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃi.kɛl ke.han]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Čikel nuz || Good evening || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃi.kɛl nuz]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Nis iztenirdi? <sup>informal / s</sup> <br >Nis iztenirdis? <sup>formal / pl</sup> || What is your name? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[nis iz.tɛ.nir.di]]] <br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[nis iz.tɛ.nir.dis]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Iztenirzi [...] || My name is [...] || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[iz.tɛ.nir.zi ⸨...⸩]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Nenbu endei? <sup>informal / s</sup> <br >Nenbu endaus? <sup>formal / pl</sup>|| Where are you from? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[nɛnbu en.dɛj]]] <br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[nɛnbu en.daws]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Enzei nen [...] || I am from [...] || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[en.zɛj nɛn ⸨...⸩]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Čikel haša || Welcome || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃi.kɛl ha.ʃa]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Adelšetet pa rimcevi! || Pleased to meet you! || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[a.dɛl.ʃɛ.tɛt pa rim.d͡ʒe.vi]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Nis endei? <sup>informal / s</sup> <br >Nis endaus? <sup>formal / pl</sup> || How are you? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[nis en.dɛj]]] <br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[nis en.daws]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Čikel <br >Denil || Good <br >Bad || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃi.kɛl]]] <br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[de.nil]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Nei teni || Me too || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[nɛj te.ni]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Sunałh || Please || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[su.naːj]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Azlakšov in <sup>informal / s</sup> <br >Azlakšod in <sup>formal / pl</sup> || Excuse me || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[az.lak.ʃo vin]]]<br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[az.lak.ʃod in]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Büder || Thank you || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[by.dɛr]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Del senil <br >Äg dana || No problem <br >You are welcome || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[dɛl se.nil]]]<br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[æg da.na]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Eš gun gelnok || Likewise || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[eʃ gun gel.nok]]] | |||

|- | |||

| A ačan kursui Natal? || Does anyone here speak Natalician? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[a a.t͡ʃan kur.suj na.tald.ja]]] | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | A kurdui Natal?<sup>informal / s</sup> <br >A kurdus Natal?<sup>formal / pl</sup> || Do you speak Natalician? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[a kur.duj na.tald.ja]]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Eha <br >Ada / Mel <br >Kelševsi|| Yes <br >No <br >Maybe || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[e.ja]]] <br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ada] [mɛl]]] <br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[kɛl.ʃɛv.si]]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Nis lümekdi kel ha? || How do you pronounce this word? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[nis ly.mɛg.di kɛl ha]]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Nis kelševi [...] eš Natal? || How to say [...] in Natalician? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[nis kɛl.ʃɛ.vi ⸨...⸩ eʃ na.tald.ja]]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Kuzda nen rettivev kursui? || How many languages do you speak? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[kuz.da nɛn re.tːi.vɛv kur.suj]]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Sunałh, kur kortso || Please, speak slower || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[su.naːj kur kort.so]]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Sunałh, özše har || Please, repeat that || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[su.naːj œ.ʃːe har]]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Sunałh, tanak har || Please, write that down || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[su.naːj ta.nak har]]] | ||

|- | |||

| A göndüi? <sup>informal / s</sup> <br >A göndüs? <sup>formal / pl</sup>|| Do you understand? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[a gœn.dyj]]]<br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[a gœn.dys]]] | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Gönzüi <br >Gönzüide || I understand <br >I don’t understand || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[gœn.zyj]]] <br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[gœn.zyj.de]]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Del konru || No idea || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[dɛl kon.ru]]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

| | |||

{| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" style="text-align: center;" | |||

|+ '''Emergencies''' | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | ! colspan="3"|Phrasebook 2 | ||

|- | |||

! width="33%"|Natalician | |||

! width="33%"|English | |||

! width="33%"|IPA | |||

|- | |||

| Artanzak || Help || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ar.tan.zak]]] | |||

|- | |||

| Ensei ďehoron || It is an emergency || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[en.sɛj ðe.jo.ron]]]ˈ | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Kelirte kutzuk ödeke || Call the fire department || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ke.lir.te kud.zuk œdɛkɛ]]] | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Kelirte polise || Call the police || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ke.lir.te po.lise]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Kelirte ämbieläns || Call an ambulance || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ke.lir.te æmb.jɛ.læns]]] | |||

| | |} | ||

| | | | ||

| | {| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" style="text-align: center;" | ||

| | |+ '''Farewelling''' | ||

| | ! colspan="3"|Phrasebook 3 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! width="33%"|Natalician | ||

| | ! width="33%"|English | ||

| | ! width="33%"|IPA | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Čikel nero || Good night || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃi.kɛl ne.ro]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Una danahso <sup>informal / s</sup> <br >Unad danahso <sup>formal / pl</sup> || Sleep well || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[u.na da.naj.so]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Etel etel <br >Zlerim || Bye || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[e.tɛl e.tɛl]]] <br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[zle.rim]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Ze özrimcevi <br >Özrimcevizis || See you soon || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ze œz.rim.d͡ʒe.vi]]] <br >[[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[œz.rim.d͡ʒe.vi.zis]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Derne iuderenzikev|| Safe travels || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[der.ne ju.de.ren.zik.ɛv]]] | |||

| | |} | ||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|} | |} | ||

= | {| | ||

|- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | {| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" style="text-align: center;" | ||

! | |+ '''Food''' | ||

! colspan="3"|Phrasebook 4 | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! width="33%"|Natalician | ||

! width="33%"|English | |||

! width="33%"|IPA | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Sunałh, a förkzüi rimzi meniuvo? || Please, could I see the menu? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[su.naːj a fœrg.zyj rimzi men.ju.vo]]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Sunałh, a äg daša meniu eš Nataldha? || Please, do you have a menu in Luthic? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[su.naːj a æg daʃa men.ju eʃ na.tald.ja]]] | |||

|- | |- | ||

| A iantad? || Have you eaten? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[a jan.tad]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Konah änemil || Bon appetit || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ko.naj æ.ne.mil]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Sunałh, lezez in fuzdovo || Please, pass the salt || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[su.naːj le.zez in fuz.do.vo]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Im veganu <sup>m sg</sup> <br> Im vegana <sup>f sg</sup> <br> Ismos vegani <sup>m pl</sup> <br> Ismos vegane <sup>f pl</sup> || I am vegan <sup>m sg</sup> <br> I am vegan <sup>f sg</sup> <br> We are vegans <sup>m pl</sup> <br> We are vegans <sup>f pl</sup> || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[im veˈɡa.nu]]] <sup>m sg</sup> <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[im veˈɡa.nɐ]]] <sup>f sg</sup> <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈiz.mos veˈɡa.ni]]] <sup>m pl</sup> <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈiz.mos veˈɡa.ne]]] <sup>f pl</sup> | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Aggio allergia || I am allergic || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈad.d͡ʒo ɐl.lerˈd͡ʒi.ɐ]]] | |||

|} | |||

| | | | ||

| | {| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" style="text-align: center;" | ||

| | |+ '''Health''' | ||

| | ! colspan="3"|Phrasebook 5 | ||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! width="33%"|Luthic | ||

| | ! width="33%"|English | ||

| | ! width="33%"|IPA | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Stais betizu nu? <sup>m sg</sup> <br> Stais betiza nu? <sup>f sg</sup> <br> States betizi nu? <sup>m pl</sup> <br> States betize nu? <sup>f pl</sup> || Are you feeling better? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈstajs beˈtid.d͡zu nu]]] <sup>m sg</sup> <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈstajs beˈtid.d͡zɐ nu]]] <sup>f sg</sup> <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈsta.tes beˈtid.d͡zi nu]]] <sup>m pl</sup> <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈsta.tes beˈtid.d͡ze nu]]] <sup>f pl</sup> | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Betizâ preste || Get well soon || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[be.θidˈd͡za.p‿ˈprɛs.te]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Curâ <sup>sg</sup> <br> Curate <sup>pl</sup> || Take care of yourself <sup>sg</sup> <br> Take care of yourselves || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[k̠uˈra]]] <sup>sg</sup> <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[k̠uˈra.θe]]] <sup>pl</sup> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Veglio ganare al toeletta || I want to go to the toilet || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[vɛʎ.ʎo ɡɐˈna.re ɐl to.ɛˈlɛt.tɐ]]] | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Þaurvo aeno dottore || I need a doctor || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈθɔr.βo ˈɛ.no dotˈto.re]]] | |||

|} | |||

| | | | ||

| | {| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" style="text-align: center;" | ||

| | |+ '''Love''' | ||

| | ! colspan="3"|Phrasebook 6 | ||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! width="33%"|Luthic | ||

| | ! width="33%"|English | ||

| | ! width="33%"|IPA | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Köššezi vun || I like you || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[mis ˈpja.t͡ʃis]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Neršezi vun || I love you || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈfrɛ.d͡ʒo θux]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Piaceresti salire mis? || Would you like to go out with me? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[pjɐ.t͡ʃeˈres.ti sɐˈli.re mis]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Is ciaelibe? || Are you single? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[is ˈt͡ʃɛ.li.βe]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Is coniugatu? || Are you married? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[is ko.njuˈɡa.θu]]] <sup>m</sup> <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[is ko.njuˈɡa.θɐ]]] <sup>f</sup> | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Is scaunu <br> Is scauna || Would you like to marry me? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[is ˈsk̠ɔ.nu]]] <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[is ˈsk̠ɔ.nɐ]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|} | |} | ||

| | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | {| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" style="text-align: center;" | ||

|+ '''Travel''' | |||

! colspan="3"|Phrasebook 7 | |||

|- | |- | ||

! width="33%"|Luthic | |||

! | ! width="33%"|English | ||

! width="33%"|IPA | |||

! | |||

! | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Ce arrivo al loftoporto? || How do I get to the airport? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃe ɐrˈri.βo ɐl ˌlof.toˈpor.to]]] | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Ce arrivo all’aütostazione? || How do I get to the bus station? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃe ɐrˈri.βo ɐlˈlɐw.θo.stɐtˈt͡sjo.ne]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Ce arrivo al ferroviaria || How do I get to the train station? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[t͡ʃe ɐrˈri.βo ɐl fer.ro.viˈa.rjɐ]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Canto þatha costat? || How much does it cost? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈkan.to θɐ.tɐ ˈk̠os.tɐθ]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Stô fralosnatu <sup>m</sup> <br> Stô fralosnata <sup>f</sup> || I am lost || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈsto frɐ.lozˈna.θu]]] <sup>m</sup> <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈsto frɐ.lozˈna.θɐ]]] <sup>f</sup> | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Begio, al sinistra <br> Begio, al destra || Please, turn left <br> Please, turn right || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈbe.d͡ʒo|ɐl siˈnis.trɐ]]] <br> [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[ˈbe.d͡ʒo|ɐl ˈdes.trɐ]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Stoppau lo vagnio || Stop the car || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[stopˈpɔ.l‿lo ˈvaɲ.ɲo]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Car puosso begetare aeno hotele? || Where can I find a hotel? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[kɐr ˈpwɔs.so be.d͡ʒeˈta.re ˈɛ.no oˈtɛ.le]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Car puosso begetare aena drogheria? || Where can I find a grocery store? || [[IPA for Luthic#Standard_Ravennese_Luthic|[kɐr ˈpwɔs.so be.d͡ʒeˈta.re ˈɛ.nɐ droˈɡe.rjɐ]]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:28, 25 September 2025

This article is private. The author requests that you do not make changes to this project without approval. By all means, please help fix spelling, grammar and organisation problems, thank you. |

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

| Natalician | |

|---|---|

| Natal retti | |

Flag of the Natalician Republic | |

| Pronunciation | [na.tal re.tːi] |

| Created by | Hazer |

| Date | 2021 |

| Setting | Hazerworld |

| Native to | Natalicia; Firenia and the Kontamchian Islands |

| Ethnicity | Natalese |

| Native speakers | 37,123,487 (2021) |

Tinarian

| |

Early form | Old Natalician

|

Standard form | Standard Central Natalician (Durgum Raskaznol Natal)

|

Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | Natalicia |

Recognised minority language in | Espidon, Amarania (Dogostania) |

| Regulated by | The Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics |

A map showing the distribution of (native and non-native) speakers of Natalician in Tinaria. Dark blue is native, light blue is secondary language speaker, and cyan is minorities. | |

Natalician (/nəˈtɑlɪʃən/; endonym: Natal [na.tal] or Natal Rettive /na.tal re.tːive/) is a North Kasenian language predominantly spoken in Central East Tinaria, specifically in Natalicia, Firenia, and North-East Nirania. Beyond Natalicia, it holds official status in Budernie, Nirania, and Kannamie, and is recognized as a minority language in East Espidon and within the Dogostanian community in Eastern Amarania. Natalician shares a close linguistic relationship with other North Kasenian languages, such as Espidan and Niranian.

Modern Natalician evolved from Old Natalician, which itself descended from an extinct, unnamed language spoken by the Natalo-Kesperian tribes. Today, Natalician stands as one of the world's most significant languages, boasting the highest number of speakers among the Kasenian languages, both as a native and a second language. Approximately 65 million people worldwide speak Natalician, including 37 million native speakers.

Natalician is characterised by its lack of grammatical cases, absence of grammatical genders, minimal irregularity, and a systematic grammar. Its orthography is straightforward, devoid of digraphs, diphthongs, or similar complexities, making it an accessible language to read and learn.

History

The earliest traces of the Natalician language date back to the year 334, featuring a vocabulary and grammar markedly different from its modern descendant. The history of the Natalician language is divided into three distinct periods: Classic Natalician (334–1203), Old Natalician (1203–1540), and Modern Natalician (1540–present). As of 2021, the language is estimated to be 1,687 years old.

Classic Natalician

Also known as Poetic Natalician or the Natalo-Kesperian Language, the earliest traces of this language are found solely in ancient poetry and inscriptions on recovered artifacts. However, the NACL (Natalician Academy of Classical Languages) considers these remnants insufficient to be deemed a complete or valid representation of the spoken Natalo-Kesperian language, largely due to the dominance of illiteracy in the pre-Killistic era and the overly formal nature of the vocabulary used in these writings.

Classic Natalician's vocabulary contains numerous direct elements from the early Proto-North-Kasenian language, which eventually faded during the migratory era. This decline was influenced by cultural clashes and the increasing incorporation of loanwords.

Unfortunately, no documents from the Classic Natalician period have survived. Consequently, there is no known evidence detailing the development of the language during this primary era.

Old Natalician

Reširi ägsös nör på tånåka if kelševi wez̊en fölsi sös.

“The people have the right to write and say what they please.”

With the dawn of the Killistic era, the Natalese tribes gained access to invaluable knowledge, brought by the ascension of their proclaimed king, Ribel Zömeri. This period marked a significant rise in literacy rates within the nascent and unified Natalese monarchy, which spanned from 1203 to 1834. During this era, the Natalician language saw its first instances of written records and experienced a flourishing of printed works.

The earliest known book containing written evidence of the Natalician language is titled "Natåltïå kočåculaï orūnza" (Natalician Guide Book). This seminal work was authored and published by the late Ulun Cilesli Irkete in the year 1210. Subsequently, numerous documents have been preserved through generations and are now treasured artifacts housed in the Natalician Grand Museum of Literature and Artifacts in Celicia.

Many historians and literary scholars have debated the relationship between Classic and Old Natalician, with some arguing that they are identical. However, the scarcity of evidence has left these claims unresolved. Scholar Iček Friktinäm posits: "Old Natalician may be the result of the incorporation of new local loanwords, and the diverse dialects might have led to deviations from the Kasenian roots of the standard spoken Natalician of that time."

Old Natalician is characterized by significantly different grammar and vocabulary compared to modern Natalician. The most notable differences include the presence of vowel harmony and grammatical cases. The language featured four types of vowel harmony and three grammatical cases: Nominative, Accusative, and Genitive. Additionally, distinct suffixes and verb conjugations highlight the major grammatical differences.

Modern Natalician

Ťenałr tanakavsai der garla. Ťenałr nameš tanakavsai der ünete.

“History is written by the victor. Our history is written by the people.”

The Natalician language has been continuously evolving since the 15th century with the decline of the monarchy and the rise of Goz Hoz to power the next few centuries. Trades and exchanges between nations has allowed for a path to new loanwords added to the Natalician lexicon. This evolution continued until the establishment of the Republic in 1845 by Zafel Sörät Fortla, when the "Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics" was created and assumed responsibility for tracking the language's development.

Etymology

The name Natalicia, the Natalese and the Natalician language, originates from the Natala tribes of the Natalo-Kesperian community in central east Tinaria. The term derives from the Proto-Kasenian word Nåťåla, meaning "fairness." This evolved into Nåsåla in Old Natalician and eventually became Nasala in Modern Natalician.

Geographical Distribution

Natalician is spoken in the Natalician republic, the kingdom of Firenia, the northwestern camps of the Nirenian republic and as a minority language in Espidon and Amarania. The popularity of Natalician has increased following the Natalician Dispora program, resulting in an increase of demand for the language to be taught as a foreign language in most of Tinaria and the other three continents.

An exact global number of Natalician speakers is a matter of difference due to the several varieties of Natalician status as separate "languages" or "dialects" is disputed for political and linguistic reasons, including certain forms of Kasperian and Rufeic Natalician. With the inclusion or exclusion of said varieties, the estimate is approximately 40 million people who speak Natalician as a first language, 5 to 15 million speak it as a second language, and 40 to 50 million as a foreign language. This would imply approximately 85 to 105 million Natalician speakers worldwide.

Natalician sociolinguist Mezred Siförtah estimated a number of 150 million Natalician foreign language speakers without clarifying the criteria by which he classified a speaker.

Tinaria

As of 2024, about 40 million people, or 12% of the Tinarian Union's population, spoke Natalician as their mother tongue, making it the fourth-most widely spoken language on the continent after English, Secaltan and Amaranian, the fourth biggest language in terms of overall speakers, as well as the third most spoken native language.

Natal Koman

The area in central east Tinaria where the majority of the population speaks Natalician as a first or second language and has Natalician as a (co-)official language is called the "Natal Koman (Natalician for: 'Natalese World')". Natalician is the official or co-official language of the following countries:

- Natalicia (official)

- Firenia (official)

- The Kontamchian Islands (official)

- Søfrøzkev, Niččišey and Vørkek regions of Nirenia (co-official)

- Province of Trumuyet of Tuggol (co-official)

- The Islands of Kannamay, Binjes and Vurvuda (co-official)

Outside the Natal Koman

Natalician is a recognised minority language in the following countries:

- Espidon (in the provinces of Zafur and Iktišek)

- East of the Federal Dogostanian Republic in Amarania

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | |||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s θ | ʃ | h | ||||

| voiced | v | z ð | ʒ | ʁ | |||||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡ʃ | |||||||

| voiceless | d͡ʒ | ||||||||

| Approximant | semivowel | j | w | ||||||

| lateral | l | ||||||||

- The phoneme /ʒ/ is usually realised as /dʒ/ in many dialects. In the island dialects, it is replaced with /d͡ʒ/ when it occurs word-initially.

- /l/ can undergo delateralisation in most dialects if preceeded by /i/ - for example, senil ("problem") is pronounced /se.nij/ rather than /se.nil/.

Vowels

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |

| Close | i | y | u | |

| Near-open | æ | |||

| Open | e | œ | a | o |

The vowels of the Natalician language are, in their alphabetical order, ⟨a⟩, ⟨ä⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨ü⟩.

The Natalician vowel system can be considered as being three-dimensional, where vowels are characterised by how and where they are articulated focusing on three key features: front and back, rounded and unrounded and vowel height.

NOTE: When the vowels /i/, /u/ precede or succeed another vowel, they become /j/, /w/ respectively. If both vowels meet one another, only the /i/ will transform into a /j/ while the /u/ remains unchanged.

Orthography

Alphabet

Natalician has a straightforward orthography, meaning regular spelling with (almost) no diphthong or digraph or anything of the sort. In linguistic terms, the writing system is a phonemic orthography.

Standard Natalician alphabet

| Letter | Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Aa | a [a] | /a/ |

| Ää | ä [æ] | /æ/ |

| Bb | be [be] | /b/ |

| Cc | ce [d͡ʒe] | /d͡ʒ/ |

| Čč | če [t͡ʃe] | /t͡ʃ/ |

| Dd | de [de] | /d/ |

| Ďď | ďe [ðe] | /ð/ |

| Ee | e [e] | /ɛ/, /e/ |

| Ff | ef [ɛf] | /f/ |

| Gg | ge [ɡ] | /g/ |

| Hh | ha [ha] | /h/, /j/ |

| Ii | i [i] | /i/, /j/ |

| Jj | je [ʒe] | /ʒ/ |

| Kk | ka [ka] | /k/ |

| Ll | el [ɛl] | /l/ |

| Łł | girbit el [gir.bit ɛl] | /ː/ |

| Mm | em [ɛm] | /m/ |

| Nn | en [ɛn] | /n/ |

| Oo | o [o] | /o/ |

| Öö | ö [œ] | /œ/ |

| Pp | pe [pe] | /p/ |

| Rr | er [ɛr] | /r/ |

| Řř | eř [ɛʁ] | /ʁ/ |

| Ss | es [s] | /s/ |

| Šš | eš [ɛʃ] | /ʃ/ |

| Tt | te [te] | /t/ |

| Ťť | ťe [θe] | /θ/ |

| Uu | u [u] | /u/ |

| Üü | ü [y] | /y/ |

| Vv | ve [ve] | /v/ |

| Ww | wa [wa] | /w/ |

| Zz | ze [ze] | /z/ |

- The letter that is called Girbit El ("Silent L"), written ⟨Ł⟩ in Natalician orthography, represents vowel lengthening. It never occurs at the beginning of a word or a syllable, always follows a vowel and always preceeds a consonant. The vowel that preceeds it is lengthened.

- The letter ⟨H⟩ in Natalician orthography represents two sounds: The /h/ sound, and the /j/ sound. If the letter ⟨H⟩ is located at the beginning of the (non-compound) word, it takes the /h/ sound, otherwise it takes the /j/ sound. (e.g. Hiloh /hi.loj/ "Hello", Konah /ko.naj/ "Beautiful", Haz /haz/ "This")

Grammar

Consonant harmony

Natalician orthography reflects voice sandhi voicing, a form of consonant mutation with two consonants that meet, and the second is voiced and the first is unvoiced. The first unvoiced consonant [p t f ʃ t͡ʃ θ k s] is voiced to [b d v ʒ d͡ʒ ð ɡ z], but the orthography remains unchanged.

- Kütdüs (you drink) realises the /t/ as a /d/ due to the voiced consonant that follows; hence, it becomes /kydː.ys/.

- Äzäpzik (announcement) realises the /p/ as a /b/; hence, it becomes /æ.zæb.zik/.

NOTE: The only time a voiced consonant gets devoiced is when the voiced-voiceless pairs meet and the voiced consonant preceeds the voiceless one, resulting in a gemination of the voiceless consonant: Lüzševi /lyʃː.e.vi/ - Özse /œsː.e/ - Kodtos /kotːos/

Vowel harmony

| Natalician Vowel Harmony | Front Vowels | Back Vowels | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |||||||

| Vowel | ä | e | i | ö | ü | a | o | u | ||

| Type Ĭ (Backness + Rounding) | i | ü | a | u | ||||||

| Type Ĕ (Backness) | e | o | ||||||||

The principle of vowel harmony

- If the first vowel of a word is a back vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a back vowel; if the first is a front vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a front vowel.

- If the first vowel is unrounded, so too are subsequent vowels.

The second and third rules minimize muscular effort during speech. More specifically, they are related to the phenomenon of labial assimilation: If the lips are rounded (a process that requires muscular effort) for the first vowel they may stay rounded for subsequent vowels. If they are unrounded for the first vowel, the speaker does not make the additional muscular effort to round them subsequently.

Grammatical affixes have "a chameleon-like quality" and obey one of the following patterns of vowel harmony:

- Twofold ĕ (-e/-o): The article, for example, is -(v)e after front vowels and -(v)o after back vowels.

- Fourfold ĭ (-i/-a/-ü/-u): The verb infinitive suffix, for example, is -i or -a after unrounded vowels (front or back respectively); and -ü or -u after the corresponding rounded vowels.

- Type & 'and': The adjectival passive voice suffix, for example, is -t&t, the & being the same vowel as the previous one.

Practically, the twofold pattern (usually referred to as the type Ĕ) means that in the environment where the vowel in the word stem is formed in the front of the mouth, the suffix will take the e form, while if it is formed in the back it will take the o form. The fourfold pattern (also called the type Ĭ) accounts for rounding as well as for front/back. The type & pattern is the reppetition of the same last vowel. The following examples, based on the verbal noun suffix -zĭk, illustrate the principles of type Ĭ vowel harmony in practice: Ähräzik ("Swimming"), Okzuk ("Knowledge"), Ianzak ("Eating"), Nörzük ("Living").

Exceptions to vowel harmony

These are four word-classes that are exceptions to the rules of vowel harmony:

- Native, non-compound words, e.g. Ela "then", Čela "drink", Ťehozuk "discussion"

- Native compound words, e.g. Pave "for what"

- Foreign words, e.g. many English loanwords such as Sertifikäht (certificate), Hospitol (hospital), Kompiułter (computer)

- Invariable prefixes / suffixes:

| Invariable prefix or suffix | Natalician example | Meaning in English | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| –(v)iš | üčiš | "exit" | From üč "leave" |

| öz- | özhaša | "to return" | From haša "to come" |

| gel- | gelsincetet | "decomposed" | From since "compose" |

Note

- A native compound does not obey vowel harmony: Ras+cezil ("city center"—a place name)

- Loanwords also disobeys vowel harmony: Kofi ("Coffee")

- Every grammatical prefix disobeys the vowel harmony aswell.

Parts of speech

There are nine parts of speech (kurzuk felev) in Natalician.

- noun (iztin "name");

- pronoun (kahuče from Amaranian kayoûtshéy, or reširnel iztinev "personal names");

- adjective (oruvaš "quality");

- verb (öhker from Amaranian eiyiker, or dirzik "action");

- adverb (randara);

- postposition (hasla eř "later addition");

- conjunction (sedlek übeřre "sentence link");

- particle (meres);

- interjection (venzik rimizli "feeling manifester").

Only nouns and verbs are inflected in Natalician. An adjective can usually be treated as a noun, in which case it can also be inflected. Inflection can give a noun features of a verb such as person and tense. With inflection, a verb can become one of the following:

- verbal noun (öhkernel iztin);

- verbal adjective (öhkernel oruvaš);

- verbal adverb (öhkernel randara).

These have peculiarities not shared with other nouns, adjectives or adverbs. For example, some participles take a person the way verbs do. Also, a verbal noun or adverb can take a direct object.

There are two standards for listing verbs in dictionaries. Most dictionaries follow the tradition of spelling out the infinitive form of the verb as the headword of the entry, but others such as the Zeraltan Natalician-English Dictionary are more technical and spell out the stem of the verb instead, that is, they spell out a string of letters that is useful for producing all other verb forms through morphological rules. Similar to the latter, this article follows the stem-as-citeword standard.

- Infinitive: oruvu ("to read")

- Stem: oru- ("read")

In Natalician, the verbal stem is also the second-person singular imperative form. Example:

- oru- (stem meaning "read")

- Oru! ("Read!")

Many verbs are formed from nouns by addition of -še. For example:

- mar – "structure"

- maršo – "build / construct"

Most adjectives can be treated as nouns or pronouns. For example, ďen can mean "young", "young person", or "the young person being referred to".

Comparison of adjectives is not done by inflecting adjectives or adverbs, but by other means (described below).

Adjectives can serve as adverbs, sometimes by means of repetition:

- danah – "happy"

- danah danah – "happily"

Nouns

Inflection

A Natalician noun has no gender. There are seven regular inflectional affixes in Natalician.

| Affix | Grammatical category | Mark | Part of speech |

|---|---|---|---|

| -(v)ĕv | Number | plural | nouns |

| -'(ĭ)n | Case | genitive | nouns and noun phrases, pronouns |

| -tĕs | Aspect | progressive | gerunds or participles |

| -t&t | Tense | past (simple) | verbs |

| -(ĕ)m | Degree of comparison | comparative | adjectives and adverbs |

| -mĕ | Degree of comparison | superlative | adjectives and adverbs |

Through its presence or absence, the plural ending shows distinctions of number.

Number

A noun is made plural by addition of -(v)ev or -(v)ov (depending on the vowel harmony). When a numeral is used with a noun, however, the plural suffix is not used:

böšter "table" böšterev "tables" nav böšter "four tables"

The plural ending also allows a family (living in one house) to be designated by a single member:

ičedevev "Ičede and his family / The Ičedes"

Verbal nouns

The verbal noun is created by the addition of the suffix -zĭk and the root of the verb.

Verb Noun fas- "give" faszak "giving / donation" den- "let" denzik "allowance" kur- "speak" kurzuk "speech" dön- "ask" dönzük "question"

The verb et- "make, do" can be considered as an auxiliary verb, since for example it is often used with verbal nouns borrowed from other languages, such as Arabic:

kabul et- "accept" (kabul "[an] accepting"); reddet- "reject" (ret "[a] rejecting"); ziyaret et- "visit" (ziyaret "[a] visiting").

Considered as units, these are transitive verbs; but the nouns in them can also, by themselves, take direct objects:

Antalya'yı ziyaret "visit to Antalya".

What looks like an ablative gerund is usually an adverb; the ending -meden usually has the sense of "without". See #Adverbs below.

An infinitive in the absolute case can be the object of a verb such as iste- "want":

Kimi

some-of-them