Luthic

This article is a featured language. It was voted featured thanks to its level of quality, plausibility and usage capabilities.

Esto arteghio è ‘na rasda ascritta. Grazze þamma sina livella qaletadi, piosevoletadi gio capacitadi utilizza, fú gia ascritta votata. |

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

This article is private. The author requests that you do not make changes to this project without approval. By all means, please help fix spelling, grammar and organisation problems, thank you. |

| Luthic | |

|---|---|

| Lúthica | |

Flag of the Luthic-speaking Ravenna | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈluː.ti.kɐ] |

| Created by | Lëtzelúcia |

| Date | 2023 |

| Setting | Alternative history Italy |

| Native to | Ravenna; Ferrara and Bologna |

| Ethnicity | Luths |

| Native speakers | 249,500 (2020) |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Proto-Luthic

|

Standard form | Standard Ravennese Luthic (Lúthica)

|

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Council for the Luthic Language |

| Language codes | |

| CLCR | qlu |

| BRCL | luth |

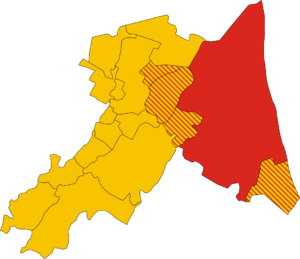

The areas where Luthic (red and orange) is spoken. | |

Luthic (/ˈluːθ.ɪk/ LOOTH-ik, less often (/ˈlʌθ.ɪk/ LUTH-ik; also Luthish; endonym: Lúthica [ˈluː.ti.kɐ] or Rasda Lúthica [ˈraz.dɐ ˈluː.ti.kɐ]) is an Italic language spoken by the Luths, with significant East Germanic influence. Unlike other Romance languages, such as Portuguese, Spanish, Catalan, Occitan, and French, Luthic preserves a substantial inherited vocabulary from East Germanic, instead of only proper names that survived in historical accounts, and loanwords. About 250,000 people speak Luthic worldwide.

The emergence of Luthic was shaped by prolonged contact between Latin speakers and East Germanic groups, particularly during the Gothic raids towards the Roman Empire and the emanation of Romano-Germanic culture following the Visigothic control over the Italian Peninsula. Later, sustained interactions with West Germanic merchants and the influence of Germanic dynasties ruling over former Roman territories and the Papal States further contributed to its development. This continuous linguistic exchange led to the formation of an interethnic koiné—a common tongue facilitating communication between Romance and Germanic speakers—which eventually evolved into what is now recognised as Luthic. Despite its clear Latin heritage, Luthic remains the subject of linguistic controversy. Some philologists classify it as essentially Romance with heavy Germanic adstrate influence, while others argue for its status as a mixed Italo-Germanic language. Within the Romance family, it is often placed in the Italo-Dalmatian group, under a proposed Gotho-Romance branch, reflecting its distinctive development.

The earliest waves of Goths who entered Italy and took part in the sack of Rome, later remembered as the Luths, created a brief context of bilingualism, the Vulgar Latin ethnolect (named Proto-Luthic by Lúcia Yamane) spoken by the early Luths bridged communication gaps and proved instrumental during the Gothic advance. Favoured by their military contribution, they briefly formed an elite under the first Ostrogothic reign, which granted their speech a status uncommon among non-Roman groups. This early prestige, combined with its flexibility in interethnic contexts, allowed Luthic to persist for centuries as a regional koiné in Ravenna. It was only with Þiuþaricu Biagchi’s Luthicæ (1657) that the language acquired a fully standardised form, securing its survival thereafter as a marker of Ravennate tradition, culture, and identity.

Structurally, Luthic shares core features with Italo-Dalmatian, Western Romance, and Sardinian, but diverges markedly from its relatives in phonology, morphology, and lexicon due to its Germanic inheritance. Its status as the regional language of Ravenna, reinforced by a language academy, has strengthened its autonomy vis-à-vis Standard Italian, its traditional Dachsprache. While sharing some typological traits with central and northern Italian dialects, Luthic maintains a distinct character shaped by centuries of sustained Germanic contact.

Luthic is an inflected fusional language, with four/five cases for nouns, pronouns (comitative forms), and adjectives (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative); three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter); and three numbers (singular, dual in personal pronouns, and plural).

Etymology

The ethnonym Luths remains one of the most debated issues in both Germanic and Romance philology. The earliest attestation appears in Greco-Roman authors of the 6th century, who mention the Lūthae (alternatively Lūthī) as one of the new barbaric peoples of Ravenna. This is usually traced back to a Gotho-Luthic lūþiks—although many scholars consider this to be a scribal error, a “correction” of *lūhtiks after influence from Latin lūthicus.

In the Gotho-Luthic language, the Luths referred to themselves collectively as the *Lūþiþiuþa “Luth people”—likely a compound of an unattested *Lūþus and þiuþa, attested as genitive plural Lūþiþiuþārum.

It is generally accepted that the Gothic letter ⟨𐌸⟩ (romanised as ⟨þ⟩) used in Gotho-Luthic represented a range of sounds, most likely both /θ/ and /tʰ/. Such ambiguity in transcription helps explain the divergent traditions in later manuscripts. A consensus has emerged that this orthographic uncertainty persisted until the so-called Luthic Reform (riforma lúthica), when spelling was standardised and the Gothic script itself gradually gave way to the Greek alphabet.

The ethnonym Lūthus appears to derive from the Gothic liuts, meaning “hypocritical” or “dishonest,” likely reflecting the disdain the Greco-Romans felt toward the barbarian kingdom and its plebeian rulers. Among the Luths themselves, however, a folk etymology emerged. They associated the name with Latin lūx, adding the common augmentative suffix -cus/-ticus to form lūcticus. This was later misinterpreted and spirantised by Gothic scribes as *lūhtiks, giving rise to the attested forms lūþiks, lūthicus and Lūthae. This folk etymology may have emerged alongside the Roman use of the term vespertīnī to describe the barbarian peoples living west of Rome—literally “toward the setting sun.” The latter, being a relational adjective to the evening, semantically changed to mean “people of the sunset” or “sunset people,” was subsequently associated with the notion of “light,” further reinforcing the Luths’ own reinterpretation of their ethnonym.

The study of Luthic

The earliest varieties of Luthic, collectively known as the Gotho-Luthic Continuum (continuo gotholúthico), emerged from sustained contact between Vulgar Latin dialects—those that would later develop into Italo-Romance varieties—and the East Germanic languages. Over the course of roughly five centuries, a significant amount of East Germanic vocabulary was absorbed into Luthic. Comparative linguistic analysis and historical records suggest that approximately 1,200 uncompounded words can be traced back to Gothic, and ultimately to Proto-Indo-European. These borrowings predominantly consist of nouns (~700), verbs (~300), and adjectives (~200), showing how East Germanic influence reached the core lexical categories. In addition, Luthic incorporated numerous loanwords from West Germanic languages during the Early Middle Ages.

The philologist Aþalphonsu Silva divided the history of Luthic into three chronological phases, collectively termed Old Luthic (500–1740):

- Gotho-Luthic — Gotholúthica (500–1100)

- Mediaeval Luthic — Lúthica mezzevale (1100–1600)

- Late Mediaeval Luthic — Lúthica siþumezzevale (1600–1740)

Later, Lúcia Yamane proposed an even earlier stage, Proto-Luthic (oslúthica), dated to c. 325–500 AD. She argued that Proto-Luthic was not yet a distinct language, but rather a Vulgar Latin ethnolect spoken by Roman and Gothic communities during their prolonged coexistence in the Empire. No texts from this phase survive—if they ever existed, they were likely lost during the Gothic War (376–382) and the sack of Rome (410). As a linguistic construct, Proto-Luthic highlights the role of sociohistorical contact in shaping Luthic, moving beyond a model of simple divergence from Latin.

The surviving Gotho-Luthic corpus is very limited and fragmentary, insufficient for a full reconstruction. Most of the extant material consists of translations or glosses of Latin and Greek texts, and thus carries the imprint of foreign linguistic influence. Even so, Gotho-Luthic was likely very close to Gothic itself, the best-documented East Germanic language, preserved most extensively in the Codex Argenteus (a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation). For Gotho-Luthic, these are the primary sources:

- Codex Luthicus (Ravenna), two parts: 87 leaves

Contains scattered passages from the New Testament (including portions of the Gospels and the Epistles), selections from the Old Testament (Nehemiah), and several commentaries. Later copyists almost certainly modified parts of the text. It was written in the Gothic alphabet, originally devised in the 4th century AD by Ulfilas (*𐍅𐌿𐌻𐍆𐌹𐌻𐌰, *Wulfila), a Gothic preacher of Cappadocian Greek descent, specifically for the purpose of translating the Bible.

- Codex Ravennas (Ravenna), four parts: 140 leaves

A civil code enacted under Theodoric the Great. While nominally covering the entire Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy, its focus was Ravenna, Theodoric’s favored capital. The Codex Ravennas was also written in the Gothic alphabet and, like the Codex Luthicus, shows signs of later scribal modification. It includes four additional leaves containing fragments of Romans 11–15, presented as a Luthic–Latin diglot.

During the mediaeval period, Luthic gradually diverged from both Latin and Gothic, taking shape as a distinct language. Latin remained the dominant written medium, but the limited Luthic texts that survive from this era were already transcribed in the Latin alphabet. Between the 7th and 16th centuries, Luthic underwent profound change under sustained contact with Old Italian, Langobardic, and Frankish.

The Carolingian conquest of the Langobards (773–774) brought northern Italy under Frankish rule, cementing Frankish influence. Charlemagne’s renewal of the Donation of the Papal States further bound the region to the papacy, reinforcing Frankish as a prestige language. Yet, as Middle Francia fragmented, the authority of Lothair I became largely nominal, and the Middle Frankish Kingdom declined in importance.

Following this collapse and the rise of the Holy Roman Empire, the conquest of Bari by Louis II in 871 strained relations with the Byzantine Empire. Consequently, Greek influence on Luthic diminished. Around this same time, the Gothic alphabet was abandoned in favor of the Latin script. However, the Latin alphabet of the 9th century lacked several symbols present in the Gothic system—such as ⟨j⟩ and ⟨w⟩—and did not yet differentiate ⟨v⟩ from ⟨u⟩. By the early 9th century, Luthic orthography began to shift. Around the 810s, the character ⟨þ⟩ was introduced, largely through contact with Old Norse and Old English, and replaced earlier symbols ⟨θ⟩ and ⟨ψ⟩, previously used interchangeably for /θ/. Some manuscripts of this era also attest to the use of ⟨y⟩ for both /v/ and /β/, likely under the influence of the Gothic letter ⟨𐍅⟩. These innovations continue to shape modern Luthic orthography, which still lacks ⟨j⟩, ⟨k⟩, and ⟨w⟩.

The first complete Luthic Bible translation marked a turning point: Luthic became a language of religion, administration, and public discourse. By the late 17th century, scholars began to codify its grammar. The most influential work was Þiuþaricu Biagchi’s De studio linguæ luthicæ (1657), a two-volume grammar written in Neo-Latin. It was granted imprimatur by Pope Alexander VII in 1656 and published on 9 September 1657.

Biagchi’s Luthicæ is widely regarded as foundational in Luthic linguistics. Beyond grammar, it addressed the relationship between Latin and the vernacular languages of Italy—an uncommon theme at the time—and introduced innovations such as diglot lemmata, enabling direct comparison of Latin and Luthic. His perspective was deeply influenced by Dante Alighieri, particularly Dante’s rejection of language as a fixed entity. Like Dante, Biagchi argued for a historical and evolutionary view of language, a principle that shaped both his scholarship and the subsequent development of Luthic.

By the early 18th century, Luthic had undergone substantial changes in vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, and orthography. Around 1730, a standardised written form began to emerge, enriched by abstract vocabulary borrowed directly from Mediaeval Latin. This process culminated in the 1750s with the spread of printed prayer books and liturgical texts, which cemented Standard Ravennese Luthic as the prestige variety.

The study of the Luthic language as an academic discipline can be traced back to Þiuþaricu’s pioneering work. Before Luthicæ, there had been no systematic attempt to analyse the language’s structure, history, and relationship with Latin and the Germanic languages. His writings laid the foundation for future scholarship, shaping the way Luthic was understood both in linguistic and cultural contexts.

In the decades following the publication of Luthicæ, scholars and clerics expanded upon Þiuþaricu’s framework, producing additional grammars, lexicons, and comparative studies. By the late 18th century, Luthic philology had become a recognised field, with academic circles debating its classification within the broader Indo-European family. Early scholars such as Marco Vegliano and Otfrid von Harenburg sought to reconcile its Romance and Germanic elements, leading to competing theories regarding its origins and evolution.

Throughout the 19th century, the formalisation of historical linguistics provided new tools for analysing Luthic. Comparative methodologies, inspired by the works of philologists such as Franz Bopp and August Schleicher, were applied to Luthic studies, further refining the understanding of its phonological and morphological shifts. By the early 20th century, Luthic linguistics had matured into a structured academic field, with dedicated university departments, linguistic societies, and journals exploring its diachronic development.

Place within the Indo-European languages

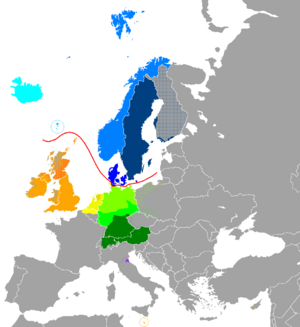

The precise classification of Luthic within the Indo-European family has long been contested. While its earliest stages display strong Gothic influence, particularly in phonology and orthography, its vocabulary and syntax reveal deep affinities with Romance, especially the Italo-Dalmatian branch. As a result, Luthic is generally regarded as a transitional language, straddling the boundary between the Gallo-Romance and East Germanic groups.

In the genealogical diagram above, Luthic is placed under the Italo-Western subgroup of Romance, alongside Italo-Dalmatian, but with a distinct Gotho-Romance layer, reflecting its mixed heritage. Some scholars, however, argue for a separate Gotho-Romance clade, encompassing both Luthic and certain extinct Gothicised dialects of northern Italy.

This hybrid status reflects the unique historical environment of Ravenna and the Po Valley: centuries of Ostrogothic rule, continued Byzantine presence, and sustained contact with both Langobardic and Frankish settlers. The resulting linguistic amalgam produced a language that cannot be reduced to either branch alone. Modern scholarship tends to describe Luthic as a Romance language with a Germanic superstratum, though a minority position still views it as a relic East Germanic tongue with heavy Romance relexification.

within the East Germanic languages, which also include The map above situates Luthic within the geographical framework of the Germanic languages, highlighting it as a possible survival of the East Germanic branch. Although this hypothesis is minor compared to the Gotho-Romance interpretation defended throughout this work, it is relevant because it suggests that Luthic might represent a missing link between Gothic and the other eastern dialects, whose early extinction left significant gaps in the reconstruction of early Germanic.

This Germanic map should not be read as a categorical definition, but as an alternative representation: a way of visualizing how different classificatory frameworks can shed light on distinct aspects of European linguistic history.

The Romance chart illustrates the general Romance linguistic landscape, foregrounding Gotho-Romance as a distinct group, though still closely related to Western Romance. Lexical differentiation, however, played a crucial role in the emergence of an independent regulatory framework for Luthic. Historically, multiple attempts were made to assimilate Luthic into the Italian dialect continuum, particularly as intermediate dialects between major Romance languages have declined over the past centuries. This shift was largely driven by speakers adopting varieties closer to prestigious national standards, contributing to the near-extinction of many regional languages.

This phenomenon has been particularly pronounced in France, where the government’s refusal to recognize minority languages has accelerated their disappearance. For decades following Italy’s unification, the Italian state adopted a similar approach toward its own ethnolinguistic minorities. Among the most notable efforts to assimilate Luthic was the so-called “Italianised Luthic Movement” (Luthic: Muovimento Lúthice Italianeggiate; Italian: Movimento per il Lutico Italianeggiato). This movement aimed to italianise Luthic’s vocabulary, systematically replacing inherited Germanic lexicon with Italic equivalents in an attempt to reinforce Luthic’s classification as an Italian-derived language. Consequently, modern Luthic orthography was significantly shaped by this initiative.

Nearly all Romance languages spoken in Italy are native to their respective regions. Apart from Standard Italian, these languages are commonly referred to as dialetti (“dialects”), both in colloquial and scholarly contexts, although alternative labels such as “minority languages” or “vernaculars” are also used in certain classifications. Italian was officially declared the national language during the Fascist period, specifically through the R.D.L. decree of 15 October 1925, Sull'Obbligo della lingua italiana in tutti gli uffici giudiziari del Regno, salvo le eccezioni stabilite nei trattati internazionali per la città di Fiume. According to UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, Italy is currently home to 32 endangered languages.

Lexis

It is generally estimated that Luthic comprises around 260,000 words—or about 380,000 when obsolete forms are included—and roughly 4 million if declined and conjugated variants are taken into account. Nevertheless, 98% of contemporary Luthic usage relies on only 3,600 words. A 2016 study by Lúcia Yamane, based on a corpus of 2,581 words selected according to frequency, semantic richness, and productivity, also incorporates lexical items formed within the Luthic territory. This study provides the following percentages:

- 723 words inherited from Gothic;

- 594 words inherited from Latin (those are not limited to the Italic lexis, including Etruscan, Greek and Celtic loanwords present in Latin);

- 335 words borrowed from Neo Latin for academic reasons (which may also include Greek loanwords);

- 310 words borrowed from Italian (which are not limited to the Italian lexicon, including also other Romance loanwords within the Italian language, such as French);

- 233 words borrowed from West Germanic languages, such as Langobardic, Frankish, Old High German, modern include Standard High German, Austrian High German and English;

- 206 words of uncertain or other origins;

- 103 words formed in Luthic;

- 77 words borrowed from Greek.

Luthic has approximately 1,300 uncompounded words inherited from Proto-Indo-European. These were inherited via:

- 44% Italic, Romance;

- 41% Germanic

- 7% Celtic;

- 2% Hellenic;

- 6% Uncertain.

A single etymological root appears in Luthic in a native form, inherited from Vulgar Latin, and a learned form, borrowed later from Classical Latin. The following pairs consist of a native noun and a learned adjective:

- finger: ditu / digitale from Latin digitus / digitālis;

- faith: fé (stem fed-) / fidele from Latin fidēs / fidēlis;

- foot: pié (stem pied-) / pedale from pēs / pedālis.

There are also noun-noun and adjective-adjective pairs with slightly different meanings:

- thing / cause: cosa / causa from Latin causa;

- bull / calf: toru / tauru from Latin taurus;

- chilled / frozen: freddu / frigidu from Latin frīgidus.

Highly preserved Germanic lexis is also visible in Luthic:

| Gothic | Old Norse | Old High German | Crimean Gothic | Luthic | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ahtau | átta | ahto | athe | attuo | eight |

| augō | auga | ouga | oeghene | uogo | eye |

| barn | barn | barn | baar | barno | ba(i)rn |

| brōþar | bróðir | bruoder | bruder | broþar | brother |

| handus | hǫnd | hant | handa | andu | hand |

| haubiþ | hǫfuð | houbit | hoef (*hoeft) | uoveþo | head |

| hlahjan | hlæja | hlahhēn | lachen | chiaire | laugh |

| qiman | koma | quëman | kommen | qemare | come |

| wair | verr | wer | fers | veru | wer |

Discussions address the different versions of Busbecq’s account, noting scribal alterations, printing errors, and subsequent corrections. His transcription and interpretation of Crimean Gothic were likely shaped by his Flemish linguistic background and perhaps also by his knowledge of German. Busbecq’s information came from a Crimean Greek informant proficient in Crimean Gothic, who was either ethnically Greek or more comfortable in Greek than in his native Gothic, though still competent in the latter. In either case, the pronunciation conveyed to Busbecq was probably influenced, at least in part, by the phonetics of contemporary Greek spoken in the region. For more, vd. Stearns Jr 1978, which is my main resource for Crimean Gothic and its corpora displayed here.

Luthic also inherited a few words, likely from Frankish, Langobardic and Old High German, which are mostly archaic, although still used in literally Luthic:

| Old High German | Old English | Modern German | Modern English | Luthic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adalheid | *Æþelhæþ | Adelheid | Adelheid | Adelaida |

| amara | amore | Ammer | ammer | amara |

| amsala | ōsle | Amsel | ouzel | asala |

| blāo | blāw | blau | blow | biau |

| ecka | ecġ | Ecke | edge | ecca |

| eiscōn | āscian | heischen | ask | aiscore |

| kamb | camb | Kamm | comb | cambu |

| mahhōn | macian | machen | make | maccore |

| swert | sweord | Schwert | sword | sverta |

From a historical perspective, the lexical evolution of Luthic reflects the dynamics of contact-induced change. Its early development, shaped by the interaction between Vulgar Latin, Gothic, and other local varieties, produced a highly permeable vocabulary, with significant borrowing and substrate influence. Over time, however, the language underwent a process of stabilisation, whereby external input decreased and internal mechanisms of lexical renewal (such as derivation and compounding) became dominant. Thus, contemporary Luthic is characterised not by openness to extensive borrowing, but by the consolidation of a relatively stable lexicon, which nonetheless bears the traces of its interethnic koiné origins.

The tables below present the lexical similarity coefficients of Luthic with both Germanic and Romance languages. The analysis was carried out by Lúcia Yamane in collaboration with the Department of Linguistics of Ravenna University, drawing on a comparative study of the 110-item Swadesh list. Each item was examined according to semantic equivalence, etymological cognacy, and phonological correspondence.

| English | Icelandic | German | Norwegian | Gothic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luthic | 50,45% | 51,13% | 53,15% | 54,05% | 62,16% |

These findings align with the hypothesis that Luthic occupies an intermediate position between the Romance and Germanic spheres, preserving features of both while maintaining a distinct lexicon. The relatively high affinity with Gothic is particularly noteworthy, as it reinforces the interpretation of Luthic as either a remnant of the East Germanic continuum or a contact-induced hybrid closely aligned with it.

| French | Latin | Spanish | Romanian | Portuguese | Sardinian | Italian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luthic | 43,24% | 44,14% | 46,84% | 47,74% | 47,74% | 48,64% | 53,13% |

Based on the 110-word list provided by the Global Lexicostatistical Database (cf. Starostin 2016a, 2016b, 2019; Kassian, Starostin, Dybo, Chernov 2010); German Swadesh list adapted from Wunderlich 2015. Adapted for the purposes of the Ravenna University project.

Comparison

| Language | Text |

|---|---|

| English | The cold winter is near, a snowstorm will come. Come in my warm house, my friend. Welcome! Come here, sing and dance, eat and drink. That is my plan. We have water, beer, and milk fresh from the cow. Oh, and warm soup! |

| Dutch | De koude winter is nabij, een sneeuwstorm zal komen, Kom in mijn warme huis, mijn vriend. Welkom! Kom hier, zing en dans, eet en drink. Dat is mijn plan. We hebben water, bier, en melk vers van de koe. Oh, en warme soep! |

| German | Der kalte Winter ist nahe, ein Schneesturm wird kommen. Komm in mein warmes Haus, mein Freund, Willkommen! Komm her, sing und tanz, iss und trink. Das ist mein Plan. Wir haben Wasser, Bier und Milch frisch von der Kuh. Oh, und warme Suppe! |

| Frisian | De kâlde winter is nei, in sniestoarm sil komme. Kom yn myn waarme hûs, myn freon. Wolkom! Kom hjir, sjong en dänsje, yt en drink. Dat is myn plan. Wy ha wetter, bier, en molke farsk fan de ko. Och, en waarme sop! |

| Norwegian | Den kalde vinteren er nær, en snøstorm vil komme. Kom inn i mitt varme hus, min venn. Velkommen! Kom her, syng og dans, et og drikk. Dette er min plan. Vi har vann, øl og melk fersk fra kua. Åh, og varm suppe! |

| Icelandic | Kaldi veturinn nálgast, snjóstormur mun koma. Komdu inn í hlýja húsið mitt, vinur minn. Velkominn! Komdu hingað, syngdu og dansaðu, borðaðu og drekktu. Það er planið mitt. Við höfum vatn, bjór, og mjólk ferska úr kúnni. Ó, og volga súpu! |

| Luthic | So caldo ventru è vicinu, iena snievosturma qemerà. Qema þa mina rasna varma, fregiondu minu! Bieneqemutu, ar qema, seggua gio danza, mangia gio dregca. Esso è so minu pianu. Vi abbiamu vato, biure, gio melucu frescu þamma vacce. Oh, gio zuppa varma! |

| Language | Text |

|---|---|

| Portuguese | Este é um magnífico palácio real. Parti, peão ignorante! Somente os elites respeitáveis em política, ciência, cultura e arte são autorizados a entrar. Retornai imediatamente à vossa fazenda miserável, e pagai a taxa, ou os guardas exterminarão a vossa família. |

| Italian | Questo è un magnifico palazzo reale. Partite, pedone ignorante! Solo le élite rispettabili in politica, scienza, cultura e arte sono autorizzate a entrare. Tornate immediatamente alla vostra misera fattoria e pagate la tassa, o le guardie stermineranno la vostra famiglia. |

| Spanish | Este es un magnífico palacio real. ¡Partí, peón ignorante! Sólo las élites respetables de la política, la ciencia, la cultura y el arte están autorizadas a entrar. Regresá inmediatamente a vuestra miserable hacienda y pagá la tasa, o los guardias exterminarán a vuestra familia. |

| French | C'est un magnifique palais royal. Partez, paysan ignorant ! Seules les élites respectables en politique, science, culture et art sont autorisées à entrer. Retournez immédiatement à votre misérable ferme. Et payez la taxe, ou les gardes extermineront votre famille. |

| Romanian | Acesta este un palat regal magnific. Îndepărtați-vă, țăranule ignorant! Doar elitele respectabile din politică, știință, cultură și artă sunt autorizate să intre. Întoarceți-vă imediat la ferma voastră mizerabilă. Și plătiți taxele, altfel gărzile vă vor extermina familia. |

| English | This is a magnificent royal palace. Depart, ignorant peasant! Only respectable elites in politics, science, culture and art are authorised to enter. Return immediately to your miserable farm. And pay the tax, or the guards will exterminate your family. |

| Luthic | Esto è ‘no magnifico palazzo reale. Partite, pedone ignorante! Sole þi eliti rispettavoli in politica, scienza, coltura gio cratte autorizzanda entrare. Tornate immediatamente aþþana vostro misero gardo gio pagate þa tassa, eþþuo sterminerano þe vargie þa vostra famiglia. |

| Language | Text |

|---|---|

| PIE | *kʷós túH h₁ési? h₁ésmi swépnos téwe témHesi nékʷti. h₁n̥gʷním dédeh₃mi téwe ḱrdéy, todéh₂ h₁wikwoph₂tḗr deywós túH h₁ési. |

| Sanskrit | Kaḥ tvám ási? Ásmi svápnaḥ táva támasvatyām náktau. Agním dadaú táva hṛdé, tadā́ viśvapitā́ deváḥ tvám ási. |

| Lithuanian | Kàs tù esì? Esù sãpnas tàvo tamsiojè naktyjè. Ùgnį daviaũ tàvo širdyjè, tadà visatė́vas diẽvas tù esì. |

| Greek | Tís sú eî? Eimí húpnos seî skoteinêi nŭktí. Pûr dídōmĭ sōî kêri, tóte păntós patḗr zeús sú eî. |

| Gothic | ƕas þū is? Im slēps riqizeinai naht þeinai. Fōn gaf hairtin þeinamma, þan allis fadar teiws þū is. |

| Latin | Quī tū es? Sum somnus tenebrosā nocte tuā. Ignem dedī cordī tuō, tum omnis pater deus tū es. |

| Luthic | Vo þú bii? Bio somnu tenebrose natte þine. Egne gevai erti þina, þan alli faþar tivu þú bii. |

| English | Who thou art? (I) am (a) sweven (in) thy dark night. (I the) fire gave (to) thy heart, then (the) father (of) all, tiw, thou art. |

Distribution

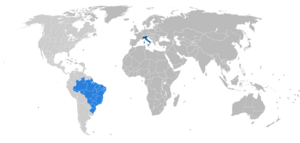

Luthic is spoken mainly in Emilia-Romagna, Italy, where it is primarily spoken in Ravenna and its adjacent communes. Although Luthic is spoken almost exclusively in Emilia-Romagna, it has also been spoken outside of Italy. Luth and general Italian emigrant communities (the largest of which are to be found in the Americas) sometimes employ Luthic as their primary language. The largest concentrations of Luthic speakers are found in the provinces of Ravenna, Ferrara and Bologna (Metropolitan City of Bologna). The people of Ravenna live in tetraglossia, as Romagnol, Emilian and Italian are spoken in those provinces alongside Luthic.

According to a census by ISTAT (The Italian National Institute of Statistics), Luthic is spoken by an estimated 250,000 people, however only 149,500 are considered de facto natives, and approximately 50,000 are monolinguals.

It is also spoken in South America by the descendants of Italian immigrants, specifically in Brazil, in a census by IBGE in collaboration with ISTAT, Luthic is spoken in São Paulo by roughly 5,000 people and some 45 of whom are monolinguals, the largest concentrations are found in the municipalities of São Paulo and the ABCD Region.

As in most European countries, the minority languages are defined by legislation or constitutional documents and afforded some form of official support. In 1992, the Council of Europe adopted the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages to protect and promote historical regional and minority languages in Europe.

Luthic is regulated by the Council for the Luthic Language (Luthic: Gaforþe folla Rasda Lúthica) and the Luthic Community of Ravenna (Luthic: Gamenescape Lúthica Ravenne). The existence of a regulatory body has removed Luthic, at least in part, from the domain of Standard Italian, its traditional Dachsprache, Luthic was considered an Italian dialect like many others until about World War II, but then it underwent ausbau.

Luthic is recognised as a minor language in Ravenna. Italy’s official language is Italian, as stated by the framework law no. 482/1999 and Trentino Alto-Adige’s special Statute, which is adopted with a constitutional law. Around the world there are an estimated 64 million native Italian speakers and another 21 million who use it as a second language. Italian is often natively spoken in a regional variety, not to be confused with Italy’s regional and minority languages; however, the establishment of a national education system led to a decrease in variation in the languages spoken across the country during the 20th century. Standardisation was further expanded in the 1950s and 1960s due to economic growth and the rise of mass media and television (the state broadcaster RAI helped set a standard Italian).

Code-switching between Luthic, Emilian dialects and Italian is frequent among Luthic speakers, in both informal and formal settings (such as on television).

Luthic lexicon is discrepant from those of other Romance languages, since most of the words present in Modern Luthic are ultimately of Germanic origin. The lexical differentiation was a big factor for the creation of an independent regulatory body. There were many attempts to assimilate Luthic into the Italian dialect continuum, as in recent centuries, the intermediate dialects between the major Romance languages have been moving toward extinction, as their speakers have switched to varieties closer to the more prestigious national standards. That has been most notable in France, owing to the French government’s refusal to recognise minority languages. For many decades since Italy’s unification, the attitude of the French government towards the ethnolinguistic minorities was copied by the Italian government. A movement called “Italianised Luthic Movement” (Luthic: Muovimento Lúthice Italianeggiate; Italian: Movimento per il Lutico Italianeggiato) tried to italianase Luthic’s vocabulary and reduce the inherited Germanic vocabulary, in order to assimilate Luthic as an Italian derived language; modern Luthic orthography was affected by this movement. Almost all of the Romance languages spoken in Italy are native to the area in which they are spoken. Apart from Standard Italian, these languages are often referred to as dialetti “dialects”, both colloquially and in scholarly usage; however, the term may coexist with other labels like “minority languages” or “vernaculars” for some of them. Italian was first declared to be Italy's official language during the Fascist period, more specifically through the R.D.l., adopted on 15 October 1925, with the name of Sull'Obbligo della lingua italiana in tutti gli uffici giudiziari del Regno, salvo le eccezioni stabilite nei trattati internazionali per la città di Fiume. According to UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, there are 31 endangered languages in Italy.

Most of the Luths also speak Italian, this is commoner for Luth elders, and most of the Luth elders may speak only Italian because of the influence from the Fascist period, as the Fascist government endorsed a stringent education policy in Italy aiming at eliminating illiteracy, which was a serious problem in Italy at the time, as well as improving the allegiance of Italians to the state. The Fascist government’s first minister of education from 1922 to 1924 Giovanni Gentile recommended that education policy should focus on indoctrination of students into Fascism and to educate youth to respect and be obedient to authority. In 1929, education policy took a major step towards being completely taken over by the agenda of indoctrination.> In that year, the Fascist government took control of the authorization of all textbooks, all secondary school teachers were required to take an oath of loyalty to Fascism and children began to be taught that they owed the same loyalty to Fascism as they did to God. In 1933, all university teachers were required to be members of the National Fascist Party. From the 1930s to 1940s, Italy’s education focused on the history of Italy, displaying Italy as a force of civilization during the Roman era, displaying the rebirth of Italian nationalism and the struggle for Italian independence and unity during the Risorgimento. In the late 1930s, the Fascist government copied Nazi Germany’s education system on the issue of physical fitness and began an agenda that demanded that Italians become physically healthy. Intellectual talent in Italy was rewarded and promoted by the Fascist government through the Royal Academy of Italy which was created in 1926 to promote and coordinate Italy’s intellectual activity.

Phonology

Luthic phonology is defined by a comparatively simple vocalic system and a consonantal inventory that varies across regional varieties. The standard form, in its most complete form, counts up to eight oral vowels, five nasal vowels, two semivowels, and twenty-six consonants, though certain dialects show a more reduced consonant set alongside an expanded vowel space. Vowels are regularly lowered and retracted before /w/ (e.g. [ë̞, o̞, æ̈, ʌ, ɒ, ɑ]) and raised and fronted before /j/ (e.g. [u, e̟, o̟, ɛ̝, ɐ̝, ɔ̝, ä̝]). In areas under strong Gallo-Italic influence, particularly Lombard and Piedmontese, rounding before /w/ produces additional allophonic series ([ø, o, œ, ɐ͗, ɔ, a͗] → [ø̞̈, o̞, æ̹̈, ɔ, ɒ, ɒ]). These patterns account for the perception of “more vowels and fewer consonants” in some varieties. Historically, this phonological profile crystallised in Ravenna, where Gothic, Frankish, Langobardic, Lepontic, and Cisalpine Gaulish elements were absorbed into the local Vulgar Latin. By the 6th century, Luthic had already become the vernacular of Ravenna, its conservative base providing the foundation for the modern system described below.

| Labial | Dental/ alveolar |

Post- alveolar/ palatal |

Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |

| Stop | p b | t d | k g | |

| Affricate | t͡s d͡z | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | ||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ | |

| Approximant | j | w | ||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||

| Trill | r |

Nasals:

- /n/ is laminal alveolar [n̻]. Some dialects register a palatalised laminal postalveolar [n̠ʲ] before /t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ/.

- /ɲ/ is alveolo-palatal and always geminate when intervocalic.

- /ŋ/ is pre-velar [ŋ˖] before [k̟, ɡ̟] and post-velar [ŋ˗] before [k̠, ɡ˗]; it may also be described as an uvular [ɴ].

Plosives:

- /p/ /b/ are purely bilabial.

- /t/ and /d/ are laminal denti-alveolar [t̻, d̻].

- /k/ and /ɡ/ are pre-velar [k̟, ɡ̟] before /i, e, ɛ, j/ and post-velar [k̠, ɡ˗] before /o, ɔ, u/; which may also be described as uvulars [q, ɢ].

Affricates:

- /t͡s/ and /d͡z/ are dentalised laminal alveolar [t̻͡s̪, d̻͡z̪].

- /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are strongly labialised palato-alveolar [t͡ʃʷ, d͡ʒʷ].

Fricatives:

- /f/ and /v/ are labiodental.

- /s/ and /z/ are laminal alveolar [s̻, z̻].

- /ʃ/ is strongly labialised palato-alveolar [ʃʷ] and geminate when intervocalic.

Approximants, trill and laterals:

- /r/ is alveolar [r].

- /l/ is laminal alveolar [l̻], some dialects register a palatalised laminal postalveolar [l̠ʲ] before /t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ/.

- /ʎ/ is alveolo-palatal and always geminate when intervocalic; in many accents, it is realised as a fricative [ʎ̝].

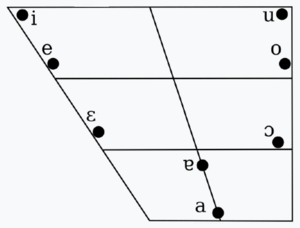

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| Close | i | ĩ | u | ũ | ||

| Close-mid | e | ẽ | o | õ | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɐ | ɐ̃ | ɔ | ||

| Open | a | |||||

- Vowels are lengthened under primary stress in open syllables, though vowel length is not phonemically distinctive. Under secondary stress in open syllables, vowels are often realised as half-long. Vowels in auslaut and nasal vowels are not affected.

- When the mid vowels /ɛ, ɔ/ precede a geminate nasal or a nasal followed by a fricative, they are realised as closer nasal vowels [ẽ] and [õ], rather than [ɛ̃] and [ɔ̃].

- All vowels tend to be lowered and retracted before /w/, yielding variants such as [ɪ, u̞, ë̞, o̞, æ̈, ʌ, ɒ, ɑ].

- Before /j/, vowels are generally raised and advanced, producing [u, e̟, o̟, ɛ̝, ɐ̝, ɔ̝, ä̝].

- In areas under stronger Gallo-Italic influence (e.g. Lombard and Piedmontese), vowels may also undergo rounding before /w/, resulting in forms like [ø̞̈, o̞, æ̹̈, ɔ, ɒ, ɒ].

- /i/ is close front unrounded [i]. F1 = 300 Hz, F2 = 2500 Hz.

- /ĩ/ is close front unrounded nasal [ĩ]. F1 = 320 Hz, F2 = 2450 Hz.

- /e/ is close-mid front unrounded [e]. F1 = 500 Hz, F2 = 2200 Hz; before /j/: F1 = 480 Hz, F2 = 2300 Hz; before /w/: F1 = 520 Hz, F2 = 2100 Hz.

- /ẽ/ is close-mid front unrounded nasal [ẽ]. F1 = 520 Hz, F2 = 2150 Hz.

- /ɛ/ is open-mid front unrounded [ɛ̝]. F1 = 600 Hz, F2 = 2000 Hz; before /j/: F1 = 580 Hz, F2 = 2100 Hz; before /w/: F1 = 620 Hz, F2 = 1900 Hz.

- /u/ is close back rounded [u]. F1 = 300 Hz, F2 = 900 Hz; before /j/: F1 = 280 Hz, F2 = 950 Hz.

- /ũ/ is close back rounded nasal [ũ]. F1 = 320 Hz, F2 = 880 Hz.

- /o/ is close-mid back rounded [o]. F1 = 500 Hz, F2 = 1100 Hz; before /j/: F1 = 480 Hz, F2 = 1150 Hz; before /w/: F1 = 520 Hz, F2 = 1050 Hz.

- /õ/ is close-mid back rounded nasal [õ]. F1 = 520 Hz, F2 = 1080 Hz.

- /ɔ/ is open-mid back rounded (slightly fronted) [ɔ̟]. F1 = 600 Hz, F2 = 1200 Hz; before /j/: F1 = 580 Hz, F2 = 1250 Hz; before /w/: F1 = 620 Hz, F2 = 1150 Hz.

- /ɐ/ is near-open central unrounded [ɐ]. F1 = 650 Hz, F2 = 1600 Hz; before /j/: F1 = 630 Hz, F2 = 1650 Hz; before /w/: F1 = 670 Hz, F2 = 1550 Hz.

- /ɐ̃/ is near-open central unrounded nasal [ɐ̃]. F1 = 670 Hz, F2 = 1550 Hz.

- /a/ is open front/central unrounded [a~ä]. F1 = 700 Hz, F2 = 1700 Hz; before /j/: F1 = 680 Hz, F2 = 1750 Hz; before /w/: F1 = 720 Hz, F2 = 1650 Hz.

It has been observed that word-final /i, u/ are raised and end in a voiceless vowel: [ii̥, uu̥]. These voiceless vowels may sound almost like [ç] and [x], particularly around Lugo, and are sometimes transcribed as [ii̥ᶜ̧, uu̥ˣ] or [iᶜ̧, uˣ]. In the same region, interconsonantal lax variants [i̽, u̽] are common, often accompanied by a schwa-like off-glide [i̽ə̯, u̽ə̯], which can be further described as an extra-short schwa-like off-glide [ə̯̆] ([i̽ə̯̆, u̽ə̯̆] or [i̽ᵊ, u̽ᵊ]). The status of [ɛ] and [ɔ] remains debated. It is often suggested that the long vowel phonemes present in Gothic developed into schwa-glides [ɛə̯̆, ɔə̯̆], or even into quasi-diphthongs [ɛæ̯̆, ɔɒ̯̆]. For simplicity, these are henceforth written as ⟨[ɛ, ɔ]⟩ due to their uncertain phonemic status.

In addition to monophthongs, Luthic has diphthongs. Phonemically and phonetically, these are simply combinations of other vowels. None of the diphthongs are considered to have distinct phonemic status, as their constituents behave the same as when occurring in isolation—unlike diphthongs in languages such as English or German. While grammatical tradition distinguishes “falling” from “rising” diphthongs, rising diphthongs consist of a semiconsonantal sound [j] or [w] followed by a vowel and therefore do not constitute true diphthongs.

| Vowel | /j/ | /w/ |

|---|---|---|

| /a/ | /aj/ /ja/ | /aw/ /wa/ |

| /ɐ/ | /ɐj/ /jɐ/ | /ɐw/ /wɐ/ |

| /ɛ/ | /ɛj/ /jɛ/ | /ɛw/ /wɛ/ |

| /e/ | /ej/ /je/ | /ew/ /we/ |

| /i/ | Ø | /wi/ |

| /ɔ/ | /ɔj/ /jɔ/ | /ɔw/ /wɔ/ |

| /o/ | /oj/ /jo/ | /ow/ /wo/ |

| /u/ | /uj/ /ju/ | Ø |

- /uj/ and /wi/ are largely in free variation. However, /wi/ occurs primarily in auslaut and inlaut positions, while /uj/ is generally found in anlaut position. The sequence /iw/ is no longer productive.

| j | o | ɔ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| j | jaj~jɐj | jej~jɛj | joj~jɔj | jwo | jwɔ |

| w | waj~wɐj | wej~wɛj | woj~wɔj | ||

- Within triphthongs, vowel quality is mostly in free variation, except in /jwo/ and /jwɔ/, where the quality is more stable. In regions influenced by Gallo-Italic languages, these clusters in /jw/ may also be reduced to [ɥ].

Phonotactics

Luthic allows up to three consonants in syllable-initial position, although there are some restrictions. Its syllable structure can be represented as (C)(C)(C)V(C)(C)(C). As in English, many words begin with three consonants. Luthic lacks true bimoraic vowels; what appear as diphthongs are actually sequences of a semiconsonantal glide [j] or [w] plus a vowel.

| C1 | C2 | C3 |

|---|---|---|

| s | p k | r j |

| s | f t | r |

| z | b | r j |

| z | d g | r |

| z | m v n d͡ʒ r l | — |

| p b f v k g | r j | — |

| t d p g | r | — |

| m n ɲ r l ʎ t͡s d͡z t͡ʃ d͡ʒ ʃ | — | — |

CC

- /s/ + any voiceless stop or /f/;

- /z/ + any voiced stop, /v d͡ʒ m n l r/;

- /f v/, or any stop + /r/;

- /f v/, or any stop except /t d/ + /j/;

- /f v s z/, or any stop or nasal + /j w/;

CCC

- /s/ + voiceless stop or /f/ + /r/;

- /s/ + /p k/ + /j/;

- /z/ + /b/ + /j/;

- /f v/ or any stop + /r/ + /j w/;

- /f v/ or any stop or nasal + /w/ + /j/.

| V1 | V2 | V3 |

|---|---|---|

| a ɐ e ɛ | i [j] u [w] | — |

| o ɔ | i [j] | — |

| i [j] | e o | — |

| i [j] | ɐ ɛ ɔ | i [j] |

| i [j] | u [w] | o |

| u [w] | ɐ ɛ ɔ | i [j] |

| u [w] | e o | — |

| u [w] | i [j] | — |

Prosody

Luthic is quasi-paroxytonic, meaning that most words receive stress on the penultimate syllable. Monosyllabic words generally lack stress unless emphasised or accentuated. Enclitic and other unstressed personal pronouns do not affect stress patterns. Some monosyllabic words may carry natural stress, though it is weaker than the stress found in polysyllabic words.

- rasda [ˈraz.dɐ];

- approssimativamente [ɐp.pros.si.mɐ.ti.vɐˈmen.te].

Compound words have secondary stress on their penultimate syllable. Some suffixes also maintain the suffixed word secondary stress.

- panzar + campu + vagnu > panzarcampovagnu [ˌpan.t͡sɐrˌkam.poˈvaɲ.ɲu];

- broþar + -scape > broþarscape [ˌbroˑ.dɐrˈska.pe].

Orthography

Luthic has a shallow orthography, meaning that spelling is highly regular and corresponds almost one-to-one with sounds. In linguistic terms, the writing system is close to a phonemic orthography. The most important exceptions are the following:

- ⟨ph, th, ch⟩ are Greco-Roman digraphs that remain productive, irregularly corresponding to /f, t, k/.

- ⟨c⟩ corresponds to /k/ in auslaut and before ⟨a, o, u⟩; before ⟨e, i⟩, it represents /t͡ʃ/.

- ⟨ch⟩ is used to represent /k/ before ⟨e, i⟩.

- ⟨g⟩ corresponds to /ɡ/ in auslaut and before ⟨a, o, u⟩; before ⟨e, i⟩, it represents /d͡ʒ/. Furthermore, before ⟨c, g, q⟩, it corresponds to /ŋ/.

- ⟨gh⟩ is used to represent /ɡ/ before ⟨e, i⟩.

- ⟨n⟩ is inserted before ⟨c, g⟩ when those consonants are palatalised, as in ogghia [ˈoŋ˖.ɡ̟jɐ] vs angio [ˈan̠ʲ.d͡ʒo].

- ⟨sc⟩ is realised as /sk/ before ⟨a, o, u⟩ and as /ʃ/ before ⟨e, i⟩; in intervocalic position, it is always geminate.

- ⟨ci, gi⟩ are realised as /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ before ⟨a, o, u⟩, without any /i~j/ glide. For /t͡ʃi.V/ and /d͡ʒi.V/, ⟨cï, gï⟩ are used, e.g., pharmacïa [fɐr.mɐˈt͡ʃiː.ɐ] and biologïa [bjo.loˈd͡ʒiː.ɐ].

- ⟨gl, gn⟩ correspond to /ʎ, ɲ/. In some cases, due to historical spelling, ⟨gli, gni⟩ are used instead, e.g. pugnu [ˈpuɲ.ɲu] (from Latin pugnus) and meraviglia [me.rɐˈviʎ.ʎɐ] (from Latin mī̆rābilia).

- ⟨s⟩ corresponds to /s/ at the onset of a syllable before a vowel, when clustered with a voiceless consonant (⟨p, f, c, q⟩), or when geminate (⟨ss⟩). It corresponds to /z/ when occurring between vowels or when clustered with voiced consonants.

- ⟨þ⟩ behaves like ⟨s⟩, corresponding to both /t d/ and voicing to /d/ in the same contexts.

- ⟨z⟩ undergoes irregular voicing due to historical phonological processes, as in mezzu [ˈmɛd.d͡zu] (from Latin medius), ziu [ˈt͡siː.u] (from Latin thius), and -zzone [-tˈt͡soː.ne] (from Latin -tiōnem).

- Length is distinctive for all consonants except for /d͡z/, /ʎ/, /ɲ/, which are always geminate intervocalically; and /z/, which is always single.

- Both acute and grave accents are used over a vowel to indicate irregular stress. ⟨á, é, í, ó, ú⟩ are realised as [ˈa ˈe ˈi ˈo ˈu], and ⟨è, ò⟩ are realised as [ˈɛ ˈɔ].

The Luthic alphabet is considered to consist of 22 letters; j, k, w, x, y are excluded, and often avoided in loanwords, as tassi vs taxi, cenophobo vs xenofobo, gine vs jeans, Giorche vs York, Valsar vs Walsar. Loanwords are also changed to fit into regular declension patterns, as seen in gine.

| Letter | Name | Historical name | IPA | Diacritics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A, a | a [ˈa] | asgo [ˈaz.go] | /ɐ/ or /a/ | á |

| B, b | bi [ˈbi] | berca [ˈbɛr.ke] | /b/ | — |

| C, c | ci [ˈt͡ʃi] | cosmo [ˈkoz.mo] | /k/, /t͡ʃ/ | — |

| D, d | di [ˈdi] | dagu [ˈdaː.g-u] | /d/ | — |

| E, e | e [ˈɛ] | ievu [ˈjɛː.vu] | /e/ or /ɛ/ | é, è |

| F, f | effe [ˈɛf.fe] | fièu [ˈfjɛː.u] | /f/ | — |

| G, g | gi [ˈd͡ʒi] | geva [ˈd͡ʒeː.ve] | /g/, /d͡ʒ/ or /ŋ/ | — |

| H, h | acca [ˈak.ke] | aghiu [ˈaː.gju] | Ø | — |

| I, i | i [ˈi] | issu [ˈis.su] | /i/ or /j/ | í, ï |

| L, l | elle [ˈɛl.le] | lagu [ˈlaː.g-u] | /l/ | — |

| M, m | emme [ˈẽ.me] | manno [ˈmẽ.no] | /m/ | — |

| N, n | enne [ˈẽ.ne] | nuoþu [ˈnwoː.du] | /n/ | — |

| O, o | o [ˈɔ] | oþalo [oˈdaː.lo] | /o/ or /ɔ/ | ó, ò |

| P, p | pi [ˈpi] | perþa [ˈpɛr.te] | /p/ | — |

| Q, q | qi [ˈkwi] | qoppa [ˈkwɔp.pe] | /kw/ | — |

| R, r | erre [ˈɛr.re] | rieþa [ˈrjɛː.de] | /r/ | — |

| S, s | esse [ˈɛs.se] | sòila [ˈsɔj.le] | /s/ or /z/ | — |

| T, t | ti [ˈti] | tivu [ˈtiː.vu] | /t/ | — |

| Þ, þ | eþþe [ˈɛt.te] | þornu [ˈtɔr.nu] | /t/ or /d/ | — |

| U, u | u [ˈu] | uru [ˈuː.ru] | /u/ or /w/ | ú |

| V, v | vi [ˈvi] | vugnia [ˈvuɲ.ɲe] | /v/ | — |

| Z, z | zi [ˈt͡si] | zetta [ˈt͡sɛt.te] | /t͡s/ or /d͡z/ | — |

Letters not used in Luthic have a conventional name in modern Luthic.

| J, j | K, k | W, w | X, x | Y, y |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| giotta | cappa | doppiu vi | isse | i grieca |

| [ˈd͡ʒɔt.te] | [ˈkap.pe] | [ˌdop.pju ˈvi] | [ˈis.se] | [ˌi ˈgrjɛ.ke] |

Grammar

This section provides a concise introduction to Luthic grammar, outlining the fundamental features that shape its structure. It is not intended as an exhaustive treatment, but rather as a summary of the most salient aspects of morphology and syntax. Readers without prior knowledge of Luthic may find this overview a useful foundation. Those already familiar with these concepts may consider the section optional, as its purpose is to establish the essentials before addressing the historical and etymological developments of Luthic morphophonology in later chapters.

Nouns

Nouns inflect for case—ordered as nominative, genitive, dative, and accusative in Luthic grammar—, as well as for number, and are classified into three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter). Number is expressed through singular and plural in nouns, while the dual survives only in the personal pronominal system. Luthic nouns are grouped into five main declensional classes:

- 1. masculine, ending in -u;

- 2. feminine, ending in -a;

- 3. neuter, ending in -o;

- 4. masculine and feminine, ending in -e;

- 5. masculine, feminine and neuter, ending in -u.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -u | -i |

| gen. | -i | -i |

| acc. | -o | -e |

| dat. | -a | -a |

- Examples: domnu “lord, sir” m, figliu “son” m.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -a | -e |

| gen. | -e | -o |

| acc. | -a | -i |

| dat. | -e | -o |

- Examples: geva “gift” f, mesa “table” f.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -o | -a |

| gen. | -i | -i |

| acc. | -o | -a |

| dat. | -a | -a |

- Examples: agrano “fruit” n, bello “war” n.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -e | -i |

| gen. | -i | -i |

| acc. | -e | -i |

| dat. | -a | -i |

- Examples: staþe “place” m, amore “love m.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -e | -i |

| gen. | -e | -o |

| acc. | -e | -i |

| dat. | -e | -i |

- Examples: qene “wife” f, ette “property” f

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -u | -iu |

| gen. | -i | -evi |

| acc. | -u | -i |

| dat. | -uo | -o |

- Examples: þornu “thorn” m, portu “port, harbor” m.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -u | -iu |

| gen. | -i | -evo |

| acc. | -u | -i |

| dat. | -uo | -o |

- Examples; andu “hand” f, ieþu “manner” f.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -u | -ua |

| gen. | -i | -evi |

| acc. | -u | -ua |

| dat. | -uo | -o |

- Examples: fièu “wealth” n, cornu “horn (musical instrument)” n

There are a few minor classes, inherited directly from Gothic, called n-stems, which have four regular classes

- 1n. masculine, ending in -o;

- 2n. feminine, ending in -o;

- 3n. neuter, ending in -o;

- 4n. feminine, ending in -i;

- 1r. masculine and feminine, ending in -ar.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -o | -e |

| gen. | -i | -ani |

| acc. | -a | -e |

| dat. | -i | -a |

- Examples: biomo “flower” m, gomo “man” m.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -o | -i |

| gen. | -i | -ono |

| acc. | -o | -i |

| dat. | -o | -o |

- Examples: toggo “tongue” f, aglo “trouble” f.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -o | -ona |

| gen. | -i | -ani |

| acc. | -o | -ona |

| dat. | -i | -a |

- Examples: uogo “eye” n, erto “heart” n.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -i | -i |

| gen. | -i | -ino |

| acc. | -i | -i |

| dat. | -i | -i |

- Examples: froþi “wisdom” f, ieþi “mother” f.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -ar | -riu |

| gen. | -ri | -ri |

| acc. | -re | -ri |

| dat. | -er | -ro |

- Examples: faþar “father” m, broþar “brother” m.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -ar | -riu |

| gen. | -ri | -ro |

| acc. | -re | -ri |

| dat. | -er | -ro |

- Examples: dottar “daughter” f, svestar “sister” f.

A last irregular class is derived from Latin, namely the suffix -tās, which is classified as Class 4d.

| Case | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| nom. | -tá | -tadi |

| gen. | -tadi | -tado |

| acc. | -tade | -tadi |

| dat. | -tada | -tadi |

- Examples: fregiatá “freedom” f, magetá “ability” f.

Adjectives

Adjectives may occur either before or after the noun. The default, unmarked position is postnominal. In prenominal, the adjective can also convey nuances of meaning, such as restrictiveness or contrastive emphasis.

- Unmarked: ienu buocu rossu “a red book”;

- Marked: ienu rossu buocu “a book that is red”.

Adjectives inflect for case, gender, and number, following paradigms that are formally identical to those of nouns. They are distributed across Classes 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Luthic marks comparison through two grammatical constructions: comparative and superlative, typically formed with the suffixes -esu and -íssimu (declined in Classes 1, 2 and 3 according to the gender), respectively. A number of irregular forms also occur, mostly due to suppletion.

- Comparative: ienu buonu dagu “a good day” > ienu bateso dagu “a better day”;

- Superlative: rasna varma “warm house” > sa rasna varnissima “the warmest house”.

Superlative forms always take a definite article. Furthermore, Luthic adjectives have a weak declension inherited from Gothic, which occurs after a demonstrative or a definite article, and is identical to Classes 1n, 2n and 3n. There are no weak forms equivalent to comparative and superlative. Comparative is also declined like Classes 1n, 2n and 3n.

Pronouns

Pronouns in Luthic form a distinct subsystem of the grammar, preserving both archaisms inherited from Indo-European and introducing unique innovations. They inflect for case, number, and (in most forms) gender. Unlike nouns and adjectives, however, the first- and second-person personal pronouns retain the dual number, which otherwise survives only in this domain. The pronominal system comprises personal, possessive, demonstrative, relative, interrogative, and indefinite forms, each with its own declensional patterns and functions. First and second personal pronouns also have a special comitative form.

Personal pronouns

The subject pronoun is typically omitted, since distinctive verb conjugations make it redundant. When expressed, subject pronouns carry emphatic force.

| Case | sg. | du. | pl. |

|---|---|---|---|

| nom. | ec | ve | vi |

| gen. | mina | ogcara | nostra |

| acc. | mec | ogche | noi |

| dat. | me | ogche | noi |

| com. | meco | usco | nosco |

The dual number in Luthic, as mentioned before, is restricted to first- and second-person pronouns. It specifically denotes “we two” or “you two,” contrasting with the plural forms that refer to three or more. The following examples illustrate the difference between omitted and emphatic subject pronouns, as well as the special addressee function of the dual:

- (no pronoun) rogio. → I speak.

- (emphatic) ec rogio. → I speak (indeed) / It is I who speak.

- (no pronoun) qeþi. → We two (without clusivity distinction) talk.

- (emphatic) ve qeþi. → We two (inclusive pronoun) talk.

- (no pronoun) andiamu. → We all go.

- (emphatic) vi andiamu. → We (restricted to our group, not others) go.

| Case | sg. | du. | pl. |

|---|---|---|---|

| nom. | þú | gio | giu |

| gen. | þina | egqara | vostra |

| acc. | þuc | egqe | voi |

| dat. | þu | egqe | voi |

| com. | þuco | isco | vosco |

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| nom. | e | gia | eta |

| gen. | e | esi | e |

| acc. | ena | gia | eta |

| dat. | emma | emma | emma |

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| nom. | i | gi | gia |

| gen. | esi | eso | esi |

| acc. | i | gi | gia |

| dat. | i | i | i |

Possessive pronouns

Possessive pronouns in Luthic agree with the possessed noun in gender, number, and case, much like adjectives, and can appear either before or after the noun they modify. Their primary function is to indicate ownership or close association, and in most cases they behave morphologically as regular adjectives. Possessive pronouns lack a weak form.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | minu | mina | mino |

| gen. | mini | mine | mini |

| acc. | mino | mina | mino |

| dat. | mina | mine | mina |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | mini | mine | mina |

| gen. | mini | mino | mini |

| acc. | mine | mine | mina |

| dat. | mina | mino | mina |

Notoriously, all possessive constructions take the definitive article, which also agrees in gender, number and case. Some examples include:

- (masculine) so minu broþar. → My brother.

- (feminine) sa mina rasna. → My house.

- (neuter) þata mino agrano. → My fruit.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | þinu | þina | þino |

| gen. | þini | þine | þini |

| acc. | þino | þina | þino |

| dat. | þina | þine | þina |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | þini | þine | þina |

| gen. | þini | þino | þini |

| acc. | þine | þine | þina |

| dat. | þina | þino | þina |

In Luthic, the third-person possessive pronouns “sinu, sina, sino” are used universally for “his,” “her,” “its,” and “their,” without distinction of gender or number in the possessor. This pattern parallels Romance languages such as Italian, where “suo, sua” likewise serve multiple functions depending on context.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | sinu | sina | sino |

| gen. | sini | sine | sini |

| acc. | sino | sina | sino |

| dat. | sina | sine | sina |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | sini | sine | sina |

| gen. | sini | sino | sini |

| acc. | sine | sine | sina |

| dat. | sina | sino | sina |

Examples include:

- (his) sa sina moþar. → His mother.

- (her) so sinu vagnu. → Her car.

- (their) sa sina famiglia. → Their family.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | ogcru | ogcra | ogcro |

| gen. | ogcri | ogcre | ogcri |

| acc. | ogcro | ogcra | ogcro |

| dat. | ogcra | ogcre | ogcra |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | ogcri | ogcre | ogcra |

| gen. | ogcri | ogcro | ogcri |

| acc. | ogcre | ogcre | ogcra |

| dat. | ogcra | ogcro | ogcra |

Some examples include:

- Þe ogcri tue buochi. → Our two books (two books that belong to us two).

- Þe ogcri figlii. → Our two children (the children that belong to us two).

Note that in Luthic the possessive dual specifies both the two possessors and, in some contexts, the exact quantity of what is possessed. In the first example, the phrase denotes exactly two books belonging to us two (one for each). In the second, the number of children is unspecified, but they are understood as belonging to a couple.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | egcru | egcra | egcro |

| gen. | egcri | egcre | egcri |

| acc. | egcro | egcra | egcro |

| dat. | egcra | egcre | egcra |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | egcri | egcre | egcra |

| gen. | egcri | egcro | egcri |

| acc. | egcre | egcre | egcra |

| dat. | egcra | egcro | egcra |

Some examples include:

- Þi ogcre tue tazze. → Your two cups (two cups that belong to you two).

- Þe ogcri fregiondi. → Your two friends (friends that you two have).

Note that in this example the possessive dual veve specifies that the cups belong to “you two.” A natural context would be three friends drinking coffee, when one points to the cups of the other two and says: “your two cups.” Here the dual makes explicit that the possession is limited to exactly those two people and each having a cup, distinguishing it from a plural form that might include others. In the second phrase, the number of friends of the two listeners is not specific.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | nostru | nostra | nostro |

| gen. | nostri | nostre | nostri |

| acc. | nostro | nostra | nostro |

| dat. | nostra | nostre | nostra |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | nostri | nostre | nostra |

| gen. | nostri | nostro | nostri |

| acc. | nostri | nostre | nostra |

| dat. | nostra | nostro | nostra |

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | vostru | vostra | vostro |

| gen. | vostri | vostre | vostri |

| acc. | vostro | vostra | vostro |

| dat. | vostra | vostre | vostra |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | vostri | vostre | vostra |

| gen. | vostri | vostro | vostri |

| acc. | vostri | vostre | vostra |

| dat. | vostra | vostro | vostra |

Demonstrative pronouns

The Luthic demonstrative system distinguishes three degrees of distance: proximal, referring to entities near the speaker; medial, for entities closer to the listener; and distal, for entities far from both speaker and listener.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | este | esta | esto |

| gen. | esti | este | esti |

| acc. | esto | esta | esto |

| dat. | esta | este | esta |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | esti | este | esta |

| gen. | esti | esto | esti |

| acc. | esti | este | esta |

| dat. | esta | esto | esta |

The proximal refers to entities near the speaker. In temporal contexts, it refers to the present.

- (space) este è so minu buocu. → This (the book the speaker holds) is my book.

- (time) esta veca è folla. → This (current) week is packed.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | esse | essa | esso |

| gen. | essi | esse | essi |

| acc. | esso | essa | esso |

| dat. | essa | esse | essa |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | essi | esse | essa |

| gen. | essi | esso | essi |

| acc. | essi | esse | essa |

| dat. | essa | esso | essa |

The medial refers to entities near the listener. In temporal contexts, it refers to the near past or near future.

- (space) essa tazza è þina? → Is that cup (near the listener) yours?

- (time) esso domnico garraggio. → I’m going this Sunday.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | gienu | giena | gieno |

| gen. | gieni | giene | gieni |

| acc. | gieno | giena | gieno |

| dat. | giena | giene | giena |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | gieni | giene | giena |

| gen. | gieni | gieno | gieni |

| acc. | giene | giene | giena |

| dat. | giena | gieno | giena |

The distal refers to entities far from the speaker and the listener. In temporal contexts, it refers to the distant past and distant future.

- (space) sevisti gieno ondo? → Did you see that dog?

- (time) gieno attomo giero fú buono. → This last year was good.

Relative pronouns

Luthic uses distinct relative pronouns depending on the type of antecedent. For people or things, the quasi-indeclinable pronoun í is used, with the genitive form ei serving as “whose.” For places, the relative pronoun var is employed, while van is used to refer to time. These pronouns consistently introduce relative clauses and do not change according to number or case.

- S’ondu, í ar stava è fiú carinu. → The dog that was here is very cute.

- Adelaida è sa ragazza, meþ í aþþa Francia vratoraggio. → Adelaida is the girl with whom I will travel to France.

- Este è so manno, ei sunu ieri qemé. → This is the man whose son arrived yesterday.

- È ‘na segguatrice, ei þ'arvèþe ammiro. → She is a singer whose work I admire.

- So staþe var buo è ferra sa mina ufficia. → The place where I live is far from my office.

- Andavo sa mina ieþi van so minu faþar arrivò. → I was walking with my mother when my father arrived.

When using the relative pronoun í and its genitive variation for people or things, the relative clause is set off by a comma.

Interrogative pronouns

Interrogative pronouns in Luthic are used to form questions about persons, objects, or qualities.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| nom. | vo | va | vata |

| gen. | ve | vesi | ve |

| acc. | vana | va | vata |

| dat. | vamma | vamma | vamma |

- (interrogative) who, what.

- (interrogative, in genitive) whose.

- (interrogative, in accusative and dative) whom.

- (interrogative, in dative) with whom, with what, how, in what way.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | vaie | vaia | vai |

| gen. | vaie | vaisi | vaie |

| acc. | vaiana | vaia | vai |

| dat. | vaiamma | vaiamma | vaiamma |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | vaie | vaii | vaia |

| gen. | vaisi | vaiso | vaisi |

| acc. | vaie | vaii | vaia |

| dat. | vaie | vaie | vaie |

Indefinite pronouns

Indefinite pronouns in Luthic express general or nonspecific reference to persons, objects, or quantities. They include forms equivalent to someone, something, anyone, nothing, and so on.

- (some) ieni, iene, iena (Classes 1, 2 & 3 plurale tantum);

- (all) alli, alle, alla (Classes 1, 2 & 3 plurale tantum);

- (each) almanno (Class 1n);

- (any) ullu (Class 1);

- (something) vocosa (Class 2);

- (nothing) necosa (Class 2);

- (everything) alcosa (Class 2);

- (anything) ulcosa (Class 2);

- (someone, somebody, anyone, anybody) vomanno (Class 1n), persona (Class 2);

- (none, no one, nobody) nemanno (Class 1n);

- (everyone, everybody) manne (Class 1n plurale tantum);

- (anyone, anybody) vogqa (Class 2);

- (nowhere, anywhere, somewhere, everywhere) varogqa (Class 2).

Articles

Articles in Luthic function as markers of definiteness and indefiniteness. As in the Romance languages, they agree with the noun in gender and number. The definite article is obligatory before possessives and many other noun phrases, while the indefinite article is used primarily in the singular.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| nom. | so, s’ | sa, s’ | þata, þat’ |

| gen. | þe | þesi | þe |

| acc. | þana, þan’ | þa, þ’ | þata, þat’ |

| dat. | þamma, þamm’ | þamma, þamm’ | þamma, þamm’ |

| Plural | |||

| nom. | þe | þi | þa |

| gen. | þesi | þeso | þesi |

| acc. | þe | þi | þa |

| dat. | þe | þe | þe |

Some examples include:

- (masculine) so ragazzu. → The boy.

- (feminine) sa ragazza. → The girl.

- (neuter) þata lico. → The body.

- (elision) þat’uoveþo. → The head.

Before vowels, the article undergoes elision, resulting in the contracted form l’, which attaches directly to the following word. This process reflects the general tendency in Luthic to avoid hiatus.

| Case | m. | f. | n. |

|---|---|---|---|

| nom. | ienu, ien’ | iena, ien’ | ieno, ien’ |

| gen. | ieni | iene | ieni |

| acc. | ieno, ien’ | iena, ien’ | ieno, ien’ |

| dat. | iena | iene | iena |

- (initial elision) essa è ‘na rasna. → This is a house.

- (terminal elision) ien’uovo. → An egg.

Verbs

Verbs in Luthic form the backbone of sentence structure, expressing actions, states, and processes through a richly inflected system. They conjugate for person, number, tense, mood, and voice, with endings that vary according to conjugational class.

Present

The present tense in Luthic is employed not only to describe actions taking place at the moment of speaking, but also to express habitual activities, ongoing states or conditions, and actions planned to occur in the near future. The four classes of verbs (conjugation’s patterns) are distinguished by the infinitive’s endings form of the verb:

1st conjugation: -are (þorvare); 2nd conjugation: -ere (credere); 3rd conjugation: -ore (olore); 4th conjugation: -ire (dormire).

| ind.act. | -are | -ere | -ore | -ire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | -o | -o | -o | -o |

| þú | -i | -i | -i | -i |

| e | -a | -e | -o | -i |

| ve | -i | -i | -i | -i |

| gio | -aze | -eze | -oze | -ize |

| vi | -iamu | -iamu | -iamu | -iamu |

| giu | -ate | -ete | -ote | -ite |

| i | -ano | -ono | -ono | -ono |

In the default active voice, the grammatical subject is the agent performing the action. Conversely, the passive voice is a construction used to shift the focus of the sentence to the patient (the receiver of the action), which then functions as the grammatical subject. The original agent, if expressed, is typically relegated to an oblique phrase. In a notable archaism, Luthic preserves a fusional passive voice. Unlike the analytical passive of modern Romance, the Luthic passive is not formed with an auxiliary verb. Instead, it is marked by a distinct set of inflectional endings applied directly to the verb stem.

| Indicative passive | -are | -ere | -ore | -ire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | -ara | -era | -ora | -ira |

| þú | -asa | -esa | -osa | -isa |

| e | -aþa | -eþa | -oþa | -iþa |

| ve | -anda | -enda | -onda | -inda |

| gio | -anda | -enda | -onda | -inda |

| vi | -anda | -enda | -onda | -inda |

| giu | -anda | -enda | -onda | -inda |

| i | -anda | -enda | -onda | -inda |

In addition to the indicative mood, which is used for factual statements and objective realities, Luthic employs a distinct subjunctive mood. The subjunctive is primarily used to express subjectivity, uncertainty, or irrealis. It typically appears in subordinate clauses, often following verbs of opinion, desire, or necessity.

| Subjunctive active | -are | -ere | -ore | -ire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | -i | -a | -i | -a |

| þú | -i | -a | -i | -a |

| e | -i | -a | -i | -a |

| ve | -i | -a | -i | -a |

| gio | -iaze | -iaze | -iaze | -iaze |

| vi | -iamu | -iamu | -iamu | -iamu |

| giu | -iate | -iate | -iate | -iate |

| i | -ino | -ano | -ino | -ano |

| Subjunctive passive | -are | -ere | -ore | -ire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | -iruo | -aruo | -iruo | -aruo |

| þú | -isuo | -asuo | -isuo | -asuo |

| e | -iþuo | -aþuo | -iþuo | -aþuo |

| ve | -induo | -anduo | -induo | -anduo |

| gio | -induo | -anduo | -induo | -anduo |

| vi | -induo | -anduo | -induo | -anduo |

| giu | -induo | -anduo | -induo | -anduo |

| i | -induo | -anduo | -induo | -anduo |

The conditional mood in Luthic is used to express actions that are contingent upon a condition, often hypothetical or unreal. Its primary functions include:

- Expressing hypothetical outcomes, typically in the apodosis of a conditional sentence;

- Indicating the future from a past perspective (futūrum in praeteritō);

- Softening requests or statements to convey politeness;

- Conveying conjecture or probability concerning past events.

| Conditional active | -are | -ere | -ore | -ire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | -erebbi | -erebbi | -orebbi | -irebbi |

| þú | -eresti | -eresti | -oresti | -iresti |

| e | -erebbe | -erebbe | -orebbe | -irebbe |

| ve | -erebbi | -erebbi | -orebbi | -irebbi |

| gio | -ereze | -ereze | -oreze | -ireze |

| vi | -eremmu | -eremmu | -oremmu | -iremmu |

| giu | -ereste | -ereste | -oreste | -ireste |

| i | -erebberono | -erebberono | -orebberono | -irebberono |

Unlike in other tenses, the conditional passive is not formed with specific inflectional endings. Instead, it is constructed analytically, using the conditional present tense of the auxiliary verb ‘to be’ combined with the past participle of the main verb. The participle, in this periphrastic construction, agrees in gender and number with the grammatical subject.

- (active) geverebbi þana buoco. → I would give the book.

- (passive) so buocu sarebbe gevatu mina. → The book would be given by me.

Imperfect

The imperfect is a past tense in Luthic characterised by its imperfective aspect. It stands in direct contrast to the preterite, which presents past events from a perfective viewpoint (i.e., as completed, single occurrences). The imperfect, instead, describes past situations or actions without reference to their beginning or end. Its principal functions are:

- Descriptive: To set the scene or describe states and characteristics in a narrative.

- Habitual: To express actions that were repeated or customary in the past.

- Durative: To depict an ongoing action in the past, often providing a temporal frame that is interrupted by another event (typically expressed in the preterite).

The difference between imperfective and perfective aspects can be illustrated clearly with the verb vetare. The imperfect expresses being in possession of knowledge in the past, while the perfective expresses the moment of acquiring the knowledge.

- (imperfective) vetavo þa treggua. → I knew the truth.

- (perfective) vetai þa treggua. → I found out the truth.

| Indicative active | -are | -ere | -ore | -ire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | -avo | -evo | -ovo | -ivo |

| þú | -avi | -evi | -ovi | -ivi |

| e | -ava | -eva | -ova | -iva |

| ve | -avi | -evi | -ovi | -ivi |

| gio | -avaze | -evaze | -ovaze | -ivaze |

| vi | -avamu | -evamu | -ovamu | -ivamu |

| giu | -avate | -evate | -ovate | -ivate |

| i | -avano | -evano | -ovano | -ivano |

| Indicative passive | -are | -ere | -ore | -ire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | -avara | -evara | -ovara | -ivara |

| þú | -avasa | -evasa | -ovasa | -ivasa |

| e | -avaþa | -evaþa | -ovaþa | -ivaþa |

| ve | -avanda | -evanda | -ovanda | -ivanda |

| gio | -avanda | -evanda | -ovanda | -ivanda |

| vi | -avanda | -evanda | -ovanda | -ivanda |

| giu | -avanda | -evanda | -ovanda | -ivanda |

| i | -avanda | -evanda | -ovanda | -ivanda |

| Subjunctive active | -are | -ere | -ore | -ire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | -asse | -esse | -osse | -isse |

| þú | -assi | -essi | -ossi | -issi |

| e | -asse | -esse | -osse | -isse |

| ve | -assi | -essi | -ossi | -issi |

| gio | -assize | -essize | -ossize | -issize |

| vi | -assimu | -essimu | -ossimu | -issimu |

| giu | -assite | -essite | -ossite | -issite |

| i | -assino | -essino | -ossino | -issino |

The imperfect subjunctive mirrors the conditional mood in its passive formation, being constructed analytically. The participle, along with the imperfect subjunctive of the auxiliary verb ‘to be’, agrees in gender and number with the subject.

- (active) sole si so þiuþanu þ’ordene gevasse. → Only if the king gave the order.

- (passive) sole si s’ordene þamma þiuþana gevata fosse. → Only if the order were given by the king.

Perfect

The perfect tense in Luthic is characterised by a split morphological formation that depends on its grammatical voice. In the active voice, the perfect is a fusional tense, using a distinct set of endings applied directly to the verb stem. Conversely, in the passive voice, it is constructed analytically, with the present indicative of the auxiliary verb ‘to be’ combined with the past participle.