Luthic

This article is private. The author requests that you do not make changes to this project without approval. By all means, please help fix spelling, grammar and organisation problems, thank you. |

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

| Luthic | |

|---|---|

| Lûthica | |

Flag of the Luthic-speaking Ravenna | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ] |

| Created by | Lëtzelúcia |

| Date | 2023 |

| Setting | Alternative history Italy |

| Native to | Ravenna; Ferrara and Bologna |

| Ethnicity | Luths |

| Native speakers | 149,500 (2020) |

Indo-European

| |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | Italy (recognised by the Luthic Community of Ravenna) |

| Regulated by | Council for the Luthic Language |

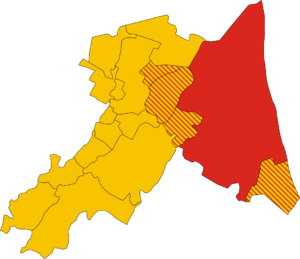

The areas where Luthic (red and orange) is spoken. | |

Luthic (/ˈluːθ.ɪk/ LOOTH-ik, less often /ˈlʌθ.ɪk/ LUTH-ik, also Luthish; endonym: Lûthica [ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ] or Rasda Lûthica [ˈʁaz.dɐ ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ]) is an Italic language that is spoken by the Luths, with strong East Germanic influence. Unlike other Romance languages, such as Portuguese, Spanish, Catalan, Occitan and French, Luthic has a large inherited vocabulary from East Germanic, instead of only proper names that survived in historical accounts, and loanwords. About 250,000 people speak Luthic worldwide.

Luthic is the result of a prolonged contact among members of both regions after the Gothic raids towards the Roman Empire began, together with the later West Germanic merchants’ travels to and from the Western Roman Empire. These connections and the conquest by the Germanic tribes of the Roman Empire slowly formed a creole for mutual communication.

As a standard form of the Gotho-Romance language, Luthic has similarities with other Italo-Dalmatian languages, Western Romance languages and Sardinian. The status of Luthic as the regional language of Ravenna and the existence there of a regulatory body have removed Luthic, at least in part, from the domain of Standard Italian, its traditional Dachsprache. It is also related to the Florentine dialect spoken by the Italians in the Italian city of Florence and its immediate surroundings.

Luthic is an inflected fusional language, with four cases for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative); three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter); and two numbers (singular, plural).

Classification

Luthic is an Indo-European language that belongs to the Gotho-Romance group of the Italic languages, however Luthic has great Germanic influence; where the Germanic languages are traditionally subdivided into three branches: North Germanic, East Germanic, and West Germanic. The first of these branches survives in modern Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Elfdalian, Faroese, and Icelandic, all of which are descended from Old Norse. The East Germanic languages are now extinct, and Gothic is the only language in this branch which survives in written texts; Luthic is the only surviving Indo-European language with extensive East Germanic derived vocabulary. The West Germanic languages, however, have undergone extensive dialectal subdivision and are now represented in modern languages such as English, German, Dutch, Yiddish, Afrikaans, and others.

Among the Romance languages, its classification has always been controversial, for example, it is one of the Italo-Dalmatian languages and most closely related to Istriot on the one hand and Tuscan-Italian on the other. Some authors include it among the Gallo-Italic languages, and according to others, it is not related to either one. Although both Ethnologue and Glottolog group Luthic into a new language group, the Gotho-Romance (opere citato) family is still somewhat dubious.

Luthic has been influenced by Italian, Frankish, Gothic and Langobardic since its first attestation, the great influence of these languages on the vocabulary and grammar of Modern Luthic is widely acknowledged. Most specialists in language contact do consider Luthic to be a true mixed language. Luthic is classified as a Romance langauge because it shares innovations with other Romance languages such as Italian, French and Spanish.

History

The Luthic philologist Aþalphonso Silva divided the history of Luthic into a period from 500 AD to 1740 to be “Mediaeval Luthic”, which he subdivided into “Gothic Luthic” (500–1100), “Mediaeval Luthic” (1100–1600) and “late Mediaeval Luthic” (1600–1740).

Gothic Luthic

The earliest varieties of a Luthic language, collectively known as Gothic Luthic or “Gotho-Luthic”, evolved from the contact of Latin dialects and East Germanic languages. A considerable amount of East Germanic vocabulary was incorporated into Luthic over some five centuries. Approximately 1,200 uncompounded Luthic words are derived from Gothic and ultimately from Proto-Indo-European. Of these 1,200, 700 are nouns, 300 are verbs and 200 are adjectives. Luthic has also absorbed many loanwords, most of which were borrowed from West Germanic languages of the Early Middle Ages.

Only a few documents in Gothic Luthic have survived – not enough for a complete reconstruction of the language. Most Gothic Luthic-language sources are translations or glosses of other languages (namely, Greek and Latin), so foreign linguistic elements most certainly influenced the texts. Nevertheless, Gothic Luthic was probably very close to Gothic (it is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text corpus). These are the primary sources:

- Codex Luthicus (Ravenna), two parts: 87 leaves

- It contains scattered passages from the New Testament (including parts of the gospels and the Epistles), from the Old Testament (Nehemiah), and some commentaries. The text likely had been somewhat modified by copyists. It was written using the Gothic alphabet, an alphabet used for writing the Gothic language. It was developed in the 4th century AD by Ulfilas (or Wulfila), a Gothic preacher of Cappadocian Greek descent, for the purpose of translating the Bible.

- Codex Ravennas (Ravenna), four parts: 140 leaves

- A civil code enacted under Theodoric the Great. The code covered the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy, but mainly Ravenna, as Theodoric devoted most of his architectural attention to his capital, Ravenna. Codex Ravennas was also written using the Gothic alphabet. The text likely had been somewhat modified by copyists. Together with four leaves, fragments of Romans 11–15 (a Luthic–Latin diglot).

Mediaeval Luthic

In the mediaeval period, Luthic emerged as a separate language from Gothic. The main written language was Latin, and the few Luthic-language texts preserved from this period are written in the Latin alphabet. From the 7th to the 16th centuries, Mediaeval Luthic gradually transformed through language contact with Old Italian, Langobardic and Frankish. During the Carolingian Empire (773–774), Charles conquered the Lombards and thus included northern Italy in his sphere of influence. He renewed the Vatican donation and the promise to the papacy of continued Frankish protection. Frankish was very strong, until Louis’ eldest surviving son Lothair I became Emperor in name but de facto only the ruler of the Middle Frankish Kingdom.

Late Mediaeval Luthic

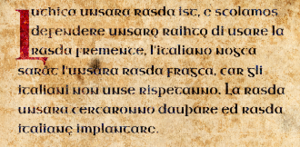

Fraugiani e Narri hanno rasda fre.

“Lords and jesters have free speech.”

Following the first Bible translation, the development of Luthic as a written language, as a language of religion, administration, and public discourse accelerated. In the second half of the 17th century, grammarians elaborated grammars of Luthic, first among them Þiudareico Bianchi’s 1657 Latin grammar De studio linguæ luthicæ.

De Studio Linguæ Luthicæ

De Studio Linguæ Luthicæ (English: On Study of the Luthic Language) often referred to as simply the Luthicæ (/lʌˈθiˌki, lʌθˈaɪˌki/ lu-THEE-KEE), is a book by Þiudareico Bianchi that expounds Luthic grammar. The Luthicæ is written in Latin and comprises two volumes, and was first published on 9 September 1657.

Book 1, De grammatica

Book 1, subtitled De grammatica (On grammar) concerns fundamental grammar features present in Luthic. It opens a collection of examples and Luthic–Latin diglot lemmata.

Book 2, De orthographia

Book 2, subtitled De orthographia (On orthography), is an exposition of the many vernacular orthographies Luthic had, and eventual suggestions for a universal orthography.

Etymology

The name of the Luths is hugely linked to the name of the Goths, itself one of the most discussed topics in Germanic philology. The autonym is attested as 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰 (gutþiuda) (the status of this word as a Gothic autonym prior to the Ostrogothic period is disputed) on the Gothic calendar (in the Codex Ambrosianus A): þize ana gutþiudai managaize marwtre jah friþareikeikeis. However, on the basis of parallel formations in Germanic (svíþjóð; angelþēod) and non-Germanic (Old Irish cruithen-tuath) indicates that it means “land of the Goths, Gothia”, instead of a more literal translation “Gothpeople”. The first element however may be also the same element attested on the Ring of Pietrossa ᚷᚢᛏᚨᚾᛁ (gutanī). Roman authors of late antiquity did not classify the Goths as Germani. While the Gutones, the Pomeranian precursors of the Goths, and the Vandili, the Silesian ancestors of the Vandals, were still considered part of Tacitean Germania, the later Goths, Vandals, and other East Germanic tribes were differentiated from the Germans and were referred to as Scythians, Goths, or some other special names. The sole exception are the Burgundians, who were considered German because they came to Gaul via Germania. In keeping with this classification, post-Tacitean Scandinavians were also no longer counted among the Germans, even though they were regarded as close relatives. The word for Luthic is first attested as 𐌻𐌿𐌸𐌹𐌺𐍃 (luþiks) on the Codex Luthicus, named after so. The name was probably first recorded via Greco-Roman writers, as *Luthae, a formation similar to Getae, itself derived from *leuhtą. Ultimately meaning the lighters.

An alternative etymology is given by the blending of latīnus and gothus, ultimately meaning Gotho-Latin. This latter etymology is unlikely.

Geographical distribution

Luthic is spoken mainly in Emilia-Romagna, Italy, where it is primarily spoken in Ravenna and its adjacent communes. Although Luthic is spoken almost exclusively in Emilia-Romagna, it has also been spoken outside of Italy. Luth and general Italian emigrant communities (the largest of which are to be found in the Americas) sometimes employ Luthic as their primary language. The largest concentrations of Luthic speakers are found in the provinces of Ravenna, Ferrara and Bologna (Metropolitan City of Bologna). The people of Ravenna live in tetraglossia, as Romagnol, Emilian and Italian are spoken in those provinces alongside Luthic.

According to a census by ISTAT (The Italian National Institute of Statistics), Luthic is spoken by an estimated 250,000 people, however only 149,500 are considered de facto natives, and approximately 50,000 are monolinguals.

Status

As in most European countries, the minority languages are defined by legislation or constitutional documents and afforded some form of official support. In 1992, the Council of Europe adopted the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages to protect and promote historical regional and minority languages in Europe.

Luthic is regulated by the Council for the Luthic Language (Luthic: Gafaurdo faul·la Rasda Lûthica [ɡɐˈfɔɾ.du fɔl‿lɐ ˈʁaz.dɐ ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ]) and the Luthic Community of Ravenna (Luthic: Gamainescape Lûthica Ravennai [ɡɐˌmɛ.neˈska.fe ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ ʁɐˈvẽ.nɛ]). The existence of a regulatory body has removed Luthic, at least in part, from the domain of Standard Italian, its traditional Dachsprache, Luthic was considered an Italian dialect like many others until about World War II, but then it underwent ausbau.

Luthic regarded as an Italian dialect

Luthic lexicon is discrepant from those of other Romance languages, since most of the words present in Modern Luthic are ultimately of Germanic origin. The lexical differentiation was a big factor for the creation of an independent regulatory body. There were many attempts to assimilate Luthic into the Italian dialect continuum, as in recent centuries, the intermediate dialects between the major Romance languages have been moving toward extinction, as their speakers have switched to varieties closer to the more prestigious national standards. That has been most notable in France, owing to the French government’s refusal to recognise minority languages. For many decades since Italy’s unification, the attitude of the French government towards the ethnolinguistic minorities was copied by the Italian government. A movement called “Italianised Luthic Movement” (Luthic: Movimento Lûthicai Italianegiatai; Italian: Movimento per il Lutico Italianeggiato) tried to italianase Luthic’s vocabulary and reduce the inherited Germanic vocabulary, in order to assimilate Luthic as an Italian derived language; modern Luthic orthography was affected by this movement.

Almost all of the Romance languages spoken in Italy are native to the area in which they are spoken. Apart from Standard Italian, these languages are often referred to as dialetti “dialects”, both colloquially and in scholarly usage; however, the term may coexist with other labels like “minority languages” or “vernaculars” for some of them. Italian was first declared to be Italy's official language during the Fascist period, more specifically through the R.D.l., adopted on 15 October 1925, with the name of Sull'Obbligo della lingua italiana in tutti gli uffici giudiziari del Regno, salvo le eccezioni stabilite nei trattati internazionali per la città di Fiume. According to UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, there are 31 endangered languages in Italy.

Standard Luthic

The basis of Standard Luthic was developed by the popular language spoken by the Ravennese people, whose was highly influenced by Gothic, together with other East Germanic substrate, such as Vandalic and Burgundian and other ancient West Germanic languages, mainly Frankish and Langobardic. Standard Luthic orthography was further influenced by Italian. Increasing mobility of the population and the dissemination of the language through mass media such as radio and television are leading to a gradual standardisation towards a “Standard Luthic” through the process of koineization.

Alphabet

Luthic has a shallow orthography, meaning very regular spelling with an almost one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds. In linguistic terms, the writing system is close to being a phonemic orthography. The most important of the few exceptions are the following (see below for more details):

- The letter c represents the sound /k/ at the end of words and before the letters a, o, and u but represents the sound /t͡ʃ/ before the letters e and i.

- The letter g represents the sound /ɡ/ at the end of words and before the letters a, o, and u but represents the sound /d͡ʒ/ before the letters e and i. It also represents the sound /ŋ/ before c or g.

- The letter r represents the sound /ʁ/ onset or stressed intervocalic, /ɾ/ when intervocalic or nearby another consonant or at the end of words and /ʀ/ if doubled.

- The cluster sc /sk/ before the letters e and i represents the sound /ʃ/, geminate if intervocalic.

- The spellings ci and gi before another vowel represent only /t͡ʃ/ or /d͡ʒ/ with no /i/ ~ /j/ sound.

- The spelling qu and gu always represent the sounds /k/ and /ɡ/.

- The spelling ġl and ġn represent the palatals /ʎ/ and /ɲ/ retrospectively; always geminate if intervocalic.

The Luthic alphabet is considered to consist of 22 letters; j, k, w, x, y are excluded, and often avoided in loanwords, as tacċi vs taxi, cċenophobo vs xenofobo, geins vs jeans, Giorque vs York, Valsar vs Walsar:

- The circumflex accent is used over vowels to indicate irregular stress.

- The digraphs ⟨ai, au, ei⟩ are used to indicate stressed /ɛ ɔ i/ retrospectively.

- In VCC structures and some Italian borrowings, the digraphs are not found.

- The overdot accent is used to over ⟨a, o⟩ to indicate coda /a o/.

- The letter o always represents the sound /u/ in coda.

- The overdot is also used over ⟨c, g⟩ to indicate palatalisation.

- The diaeresis accent is used to distinguish from a digraph or a diphthong.

- The letter ⟨s⟩ can symbolise voiced or voiceless consonants. ⟨s⟩ symbolises /s/ onset before a vowel, when clustered with a voiceless consonant (⟨p, f, c, q⟩), and when doubled (geminate); it symbolises /z/ when between vowels and when clustered with voiced consonants.

| Letter | Name | Historical name | IPA | Diacritics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A, a | a [ˈa] | asga [ˈaz.ɡɐ] | /ɐ/ or /a/ | â, ȧ |

| B, b | bi [bi] | bairka [ˈbɛɾ.kɐ] | /b/ or /ʋ/ | — |

| C, c | ci [ˈt͡ʃi] | caunȯ [ˈkɔ.no] | /k/, /t͡ʃ/ or /x/ | ċ |

| D, d | di [ˈdi] | dago [ˈda.ɣ˕u] | /d/ or /ð̞/ | — |

| E, e | e [ˈɛ] | aiqqo [ˈɛk.kʷu] | /e/ or /ɛ/ | ê |

| F, f | effe [ˈɛf.fe] | faiho [ˈfɛ.hu] | /f/ or /p͡f/ | — |

| G, g | gi [ˈd͡ʒi] | giva [ˈd͡ʒi.vɐ] | /ɡ/, /d͡ʒ/, /ɣ˕/ or /ŋ/ | ġ |

| H, h | acca [ˈak.kɐ] | haġlo [ˈhaʎ.ʎu] | /h/ or /ç/ | — |

| I, i | i [ˈi] | eisso [ˈis.su] | /i/ or /j/ | ï |

| L, l | elle [ˈɛl.le] | lago [ˈla.ɣ˕u] | /l/ | — |

| M, m | emme [ˈẽ.me] | manno [ˈmɐ̃.nu] | /m/ | — |

| N, n | enne [ˈẽ.ne] | nauþo [ˈnɔ.θu] | /n/ | — |

| O, o | o [ˈɔ] | oþalȯ [oˈθa.lo] | /o/, /u/ or /ɔ/ | ô, ȯ |

| P, p | pi [ˈpi] | pairþa [ˈpɛɾ.t͡θɐ] | /p/ or /f/ | — |

| Q, q | qoppa [ˈkʷɔp.pɐ] | qairþa [ˈkʷɛɾ.t͡θɐ] | /kʷ/ | — |

| R, r | erre [ɛˈʀe] | raida [ˈʁɛ.ð̞ɐ] | /ʀ/, /ʁ/ or /ɾ/ | — |

| S, s | esse [ɛsˈse] | sauila [ˈsɔj.lɐ] | /s/, /t͡s/ or /z/ | — |

| T, t | ti [ˈti] | teivo [ˈti.vu] | /t/ or /θ/ | — |

| Þ, þ | eþþe [ˈɛθ.θe] | þaurno [ˈθɔɾ.nu] | /θ/ or /t͡θ/ | — |

| U, u | u [ˈu] | uro [ˈu.ɾu] | /u/ or /w/ | û, ü |

| V, v | vi [ˈvi] | viġna [ˈviɲ.ɲɐ] | /v/ | — |

| Z, z | zi [ˈt͡si] | zetta [ˈt͡sɛt.tɐ] | /t͡s/ or /d͡z/ | — |

Luthic has geminate, or double, consonants, which are distinguished by length and intensity. Length is distinctive for all consonants except for /d͡z/, /ʎ/, /ɲ/ , which are always geminate when between vowels, and /z/, which is always single. Geminate plosive and affricates are realised as lengthened closures. Geminate fricatives, nasals, and /l/ are realised as lengthened continuants. When triggered by Gorgia Toscana, voiceless fricatives are always constrictive, but voiced fricatives are not very constrictive and often closer to approximants.

Phonology

There is a maximum of 8 oral vowels, 5 nasal vowels, 2 semivowels and 35 consonants; though some varieties of the language have fewer phonemes. Gothic, Frankish, northern Suebi, Langobardic, Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish (Roman Gaul) influences were highly absorbed into the local Vulgar Latin dialect. An early form of Luthic was already spoken in the Ostrogothic Kingdom during Theodoric’s reign and by the year 600 Luthic had already become the vernacular of Ravenna. Luthic developed in the region of the former Ostrogothic capital of Ravenna, from Late Latin dialects and Vulgar Latin. As Theodoric emerged as the new ruler of Italy, he upheld a Roman legal administration and scholarly culture while promoting a major building program across Italy, his cultural and architectural attention to Ravenna led to a most conserved dialect, resulting in modern Luthic.

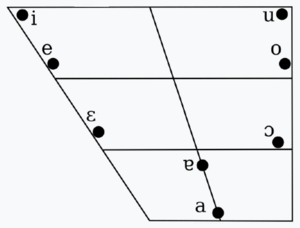

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| Close | i | ĩ | u | ũ | ||

| Close-mid | e | ẽ | o | õ | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɐ | ɐ̃ | ɔ | ||

| Open | a | |||||

Notes

When the mid vowels /ε, ɔ/ precede a nasal, they become close [ẽ] rather than [ε̃] and [õ] rather than [ɔ̃].

- /i/ is close front unrounded [i].

- /u/ is close back rounded [u].

- /e/ is close-mid front unrounded [e].

- /o/ is close-mid back rounded [o].

- /ɛ/ has been variously described as mid front unrounded [ɛ̝] and open-mid front unrounded [ɛ].

- /ɔ/ is somewhat fronted open-mid back rounded [ɔ̟].

- /ɐ/ is near-open central unrounded [ɐ].

- /a/ has been variously described as open front unrounded [a] and open central unrounded [ä].

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | (ŋʷ) | ||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | kʷ | ||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ɡʷ | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s θ | ʃ | ç | (x) | h | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ʁ | |||||

| Affricate | voiceless | (p͡f) | t͡s (t͡θ) | t͡ʃ | |||||

| voiceless | d͡z | d͡ʒ | |||||||

| Approximant | semivowel | j | w | ||||||

| lateral | l | ʎ | |||||||

| Gorgia Toscana | (ʋ) | (ð̞) | (ɣ˕) | ||||||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||||

| Trill | ʀ | ||||||||

Notes

- Nasals:

- Plosives:

- /p/, /pʰ/ and /b/ are purely labial.

- /t/, /tʰ/ and /d/ are laminal dentialveolar [t̻, t̻ʰ, d̻].

- /k/ and /ɡ/ are pre-velar [k̟, ɡ̟] before /i, e, ɛ, j/.

- /kʷ/ and /ɡʷ/ are palato-labialised [kᶣ, ɡᶣ] before /i, e, ɛ, j/.

- Affricates:

- /p͡f/ is bilabial–labiodental and is only found as a common allophone.

- /t͡θ/ is dental and is only found as a common allophone.

- /t͡s/ and /d͡z/ are dentalised laminal alveolar [t̻͡s̪, d̻͡z̪].

- /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are strongly labialised palato-alveolar [t͡ʃʷ, d͡ʒʷ].

- Fricatives:

- /f/ and /v/ are labiodental.

- /θ/ is dental.

- /s/ and /z/ are laminal alveolar [s̻, z̻].

- /ʃ/ is strongly labialised palato-alveolar [ʃʷ].

- /x/ is velar, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /ʁ/ is uvular, but in anlaut is in free variation with [h].

- /h/ is glottal, but is in free variation with [x ~ ʁ], /h/ is palatal [ç] nearby /i, e, ɛ, j/.

- Approximants, flap, trill and laterals:

- /ʋ/ is labiodental, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /ð̞/ is dental, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /j/ and /w/ are always geminate when intervocalic.

- /ɾ/ is alveolar [ɾ].

- /ɣ˕/ is velar, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /ʀ/ is uvular [ʀ], but is in free variation with alveolar [r].

- /l/ is laminal alveolar [l̻].

- /ʎ/ is alveolo-palatal, always geminate when intervocalic.

Historical phonology

The phonological system of the Luthic language underwent many changes during the period of its existence. These included the palatalisation of velar consonants in many positions and subsequent lenitions. A number of phonological processes affected Luthic in the period before the earliest documentation. The processes took place chronologically in roughly the order described below (with uncertainty in ordering as noted).

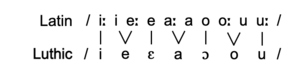

Vowel system

The most sonorous elements of the [[w:Syllable|syllable] are vowels, which occupy the nuclear position. They are prototypical mora-bearing elements, with simple vowels monomoraic, and long vowels bimoraic. Latin vowels occurred with one of five qualities and one of two weights, that is short and long /i e a o u/. At first, weight was realised by means of longer or shorter duration, and any articulatory differences were negligible, with the short:long opposition stable. Subtle articulatory differences eventually grow and lead to the abandonment of length, and reanalysis of vocal contrast is shifted solely to quality rather than both quality and quantity; specifically, the manifestation of weight as length came to include differences in tongue height and tenseness, and quite early on, /ī, ū/ began to differ from /ĭ, ŭ/ articulatorily, as did /ē, ō/ from /ĕ, ŏ/. The long vowels were stable, but the short vowels came to be realised lower and laxer, with the result that /ĭ, ŭ/ opened to [ɪ, ʊ], and /ĕ, ŏ/ opened to [ε, ɔ]. The result is the merger of Latin /ĭ, ŭ/ and /ē, ō/, since their contrast is now realised sufficiently be their distinct vowel quality, which would be easier to articulate and perceive than vowel duration.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː ĩː | u uː ũː | |

| Mid | e eː ẽː | o oː õː | |

| Open | ä äː ä̃ː |

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ɪ iː ĩː | ʊ uː ũː | |

| Mid | ε eː ẽː | ɔ oː õː | |

| Open | ä äː ä̃ː |

Unstressed a resulted in a slightly raised a [ɐ]. In hiatus, unstressed front vowels become /j/, while unstressed back vowels become /w/.

In addition to monophthongs, Luthic has diphthongs, which, however, are both phonemically and phonetically simply combinations of the other vowels. None of the diphthongs are, however, considered to have distinct phonemic status since their constituents do not behave differently from how they occur in isolation, unlike the diphthongs in other languages like English and German. Grammatical tradition distinguishes “falling” from “rising” diphthongs, but since rising diphthongs are composed of one semiconsonantal sound [j] or [w] and one vowel sound, they are not actually diphthongs. The practice of referring to them as “diphthongs” has been criticised by phoneticians like Alareico Villavolfo.

Absorption of nasals before fricatives

This is the source of such alterations as modern Standard Luthic fimfe [ˈfĩ.(p͡)fe] “five”, monþo [ˈmõ.(t͡)θu] “mouth” versus Gothic 𐍆𐌹𐌼𐍆 [ˈɸimɸ] “id.”, 𐌼𐌿𐌽𐌸𐍃 [ˈmunθs] “id.” and German fünf [fʏnf] “id.”, Mund [mʊnt] “id.”.

Monophthongization

The diphthongs au, ae and oe [au̯, ae̯, oe̯] were monophthongized (smoothed) to [ɔ, ɛ, e] by Gothic influence, as the Germanic diphthongs /ai/ and /au/ appear as digraphs written ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ in Gothic. Researchers have disagreed over whether they were still pronounced as diphthongs /ai̯/ and /au̯/ in Ulfilas' time (4th century) or had become long open-mid vowels: /ɛː/ and /ɔː/: 𐌰𐌹𐌽𐍃 (ains) [ains] / [ɛːns] “one” (German eins, Icelandic einn), 𐌰𐌿𐌲𐍉 (augō) [auɣoː] / [ɔːɣoː] “eye” (German Auge, Icelandic auga). It is most likely that the latter view is correct, as it is indisputable that the digraphs ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ represent the sounds /ɛː/ and /ɔː/ in some circumstances (see below), and ⟨aj⟩ and ⟨aw⟩ were available to unambiguously represent the sounds /ai̯/ and /au̯/. The digraph ⟨aw⟩ is in fact used to represent /au/ in foreign words (such as 𐍀𐌰𐍅𐌻𐌿𐍃 (Pawlus) “Paul”), and alternations between ⟨ai⟩/⟨aj⟩ and ⟨au⟩/⟨aw⟩ are scrupulously maintained in paradigms where both variants occur (e.g. 𐍄𐌰𐌿𐌾𐌰𐌽 (taujan) “to do” vs. past tense 𐍄𐌰𐍅𐌹𐌳𐌰 (tawida) “did”). Evidence from transcriptions of Gothic names into Latin suggests that the sound change had occurred very recently when Gothic spelling was standardised: Gothic names with Germanic au are rendered with au in Latin until the 4th century and o later on (Austrogoti > Ostrogoti).

Palatalisation

Early evidence of palatalized pronunciations of /tj kj/ appears as early as the 2nd–3rd centuries AD in the form of spelling mistakes interchanging ⟨ti⟩ and ⟨ci⟩ before a following vowel, as in ⟨tribunitiae⟩ for tribuniciae. This is assumed to reflect the fronting of Latin /k/ in this environment to [c ~ t͡sʲ]. Palatalisation of the velar consonants /k/ and /ɡ/ occurred in certain environments, mostly involving front vowels; additional palatalisation is also found in dental consonants /t/, /d/, /l/ and /n/, however, these are not palatalised in word initial environment.

- Latin amīcus [äˈmiː.kus̠ ~ äˈmiː.kʊs̠], amīcī [äˈmiː.kiː] > Luthic amico [ɐˈmi.xu], amici [ɐˈmi.t͡ʃi].

- Gothic giba [ˈɡiβa] > Luthic giva [ˈd͡ʒi.vɐ].

- Latin ratiō [ˈrä.t̪i.oː] > Luthic razione [ʁɐˈd͡zjo.ne]

- Latin fīlius [ˈfiː.li.us̠ ~ ˈfiː.lʲi.ʊs̠] > Luthic fiġlo [ˈfiʎ.ʎu].

- Latin līnea [ˈliː.ne.ä ~ ˈlʲiː.ne.ä] , pugnus [ˈpuŋ.nus̠ ~ ˈpʊŋ.nʊs̠], ācrimōnia [äː.kriˈmoː.ni.ä ~ äː.krɪˈmoː.ni.ä] > Luthic liġna [ˈliɲ.ɲɐ], poġno [ˈpoɲ.ɲu], acremoġna [ɐ.kɾeˈmoɲ.ɲɐ].

Labio-velars remain unpalatalised, except in monosyllabic environment:

- Latin quis [kʷis̠ ~ kʷɪs̠] > Luthic ce [t͡ʃe].

- Gothic qiman [ˈkʷiman] > Luthic qemare [kʷeˈma.ɾe ~ kᶣeˈma.ɾe].

Lenition

The Gotho-Romance family suffered very few lenitions, but in most cases the stops /p t k/ are lenited to /b d ɡ/ if not in onset position, before or after a sonorant or in intervocalic position as a geminate. A similar process happens with /b/ that is lenited to /v/ in the same conditions. The non-geminate rhotic present in Latin is simplified to /ɾ ʁ/. The unstressed labio-velar /kʷ/ delabialises before hard vowels, as in:

- Gothic ƕan [ʍan] > *[kʷɐn] > Luthic can [kɐn].

- Latin nunquam [ˈnuŋ.kʷä̃ː ~ ˈnʊŋ.kʷä̃ː] > Luthic nogca [ˈnoŋ.kɐ].

Luthic is further affected by the Gorgia Toscana effect, where every plosive is spirantised (or further approximated if voiced). Plosives, however, are not affected if:

- Geminate.

- Labialised.

- Nearby another fricative.

- Nearby a rhotic, a lateral or nasal.

- Stressed and anlaut.

Fortition

In every case, /j/ and /w/ are fortified to /d͡ʒ/ and /v/, except when triggered by hiatus collapse. The Germanic /ð/ and /xʷ ~ hʷ ~ ʍ/ are also fortified to /d/ and /kʷ/ in every position; which can be further lenited to /d͡z/ and /k ~ t͡ʃ/ in the environments given above. The Germanic /h ~ x/ is fortified to /k/ before a rhotic or a lateral, as in:

- Gothic hlaifs [ˈhlɛːɸs] > Luthic claifo [ˈklɛ.fu].

- Gothic hriggs [ˈhriŋɡs ~ ˈhriŋks] > Luthic creggo [ˈkɾeŋ.ɡu].

Coda consonants with similar articulations often sandhi, triggering a kind of syntactic gemination, it also happens with oxytones:

- Il catto [i‿kˈkat.tu].

- Ed þû, ce taugis? [e‿θˈθu | t͡ʃe ˈtɔ.d͡ʒis?].

- La cittâ stâþ sporca [lɐ t͡ʃitˈta‿sˈsta‿sˈspoɾ.kɐ].

Regarding the absorption of nasals before fricatives, voiceless fricatives are often fortified to affricates after alveolar consonants, such as /n l ɾ/, or general nasals:

- Il monþo [i‿mˈmõ.t͡θu].

- L’inferno [l‿ĩˈp͡fɛɾ.nu].

- La salsa [lɐ ˈsal.t͡sɐ].

- L’arsenale [l‿ɐɾ.t͡seˈna.le].

Deletion

In some rare cases, the consonants are fully deleted (elision), as in the verb havere, akin to Italian avere, which followed a very similar paradigm and evolution:

- 1st person indicative present: Latin habeō, Gothic haba, Luthic hô, Italian ho.

- 2nd person indicative present: Latin habēs, Gothic habais, Luthic haïs, Italian hai.

- 3rd person indicative present: Latin habet, Gothic habaiþ, Luthic hâþ, Italian ha.

Vowels other than /a/ are often syncopated in unstressed word-internal syllables, especially when in contact with liquid consonants:

- Latin angulus [ˈäŋ.ɡu.ɫ̪us̠ ~ ˈäŋ.ɡʊ.ɫ̪ʊs̠] > Luthic agglo [ˈaŋ.ɡlu].

- Latin speculum [ˈs̠pɛ.ku.ɫ̪ũː ~ ˈs̠pɛ.kʊ.ɫ̪ũː] ~ Luthic speclȯ [ˈspɛ.klo].

- Latin avunculus [äˈu̯uŋ.ku.ɫ̪us̠ ~ äˈu̯ʊŋ.kʊ.ɫ̪ʊs̠] > Luthic avogclo [ɐˈvoŋ.klu].

Phonotactics

Luthic allows up to three consonants in syllable-initial position, though there are limitations. The syllable structure of Luthic is (C)(C)(C)(G)V(G)(C)(C). As with English, there exist many words that begin with three consonants. Luthic lacks bimoraic (diphthongs and long vowels), as the so-called diphthongs are composed of one semiconsonantal (glide) sound [j] or [w].

| C₁ | C₂ | C₃ |

|---|---|---|

| f v p b t d k ɡ | ɾ | j w |

| s | p k | ɾ l |

| s | f t | ɾ |

| z | b | l |

| z | d ɡ | ɾ |

| z | m n v d͡ʒ ɾ l | — |

| p b f v k ɡ | ɾ l | — |

| ɡ | n l | — |

| pʰ t tʰ kʰ d | ɾ | — |

| θ | v ɾ | — |

| kʷ ɡʷ t͡s t͡ʃ d͡ʒ ʃ h ð ʁ ɲ l ʎ | — | — |

CC

- /s/ + any voiceless stop or /f/;

- /z/ + any voiced stop, /v d͡ʒ m n l ɾ/;

- /f v/, or any stop + /ɾ/;

- /f v/, or any stop except /t d/ + /l/;

- /f v s z/, or any stop or nasal + /j w/;

- In Graeco-Roman words origin which are only partially assimilated, other combinations such as /pn/ (e.g. pneumatico), /mn/ (e.g. mnemonico), /tm/ (e.g. tmesi), and /ps/ (e.g. pseudo-) occur.

As an onset, the cluster /s/ + voiceless consonant is inherently unstable. Phonetically, word-internal s+C normally syllabifies as [s.C]. A competing analysis accepts that while the syllabification /s.C/ is accurate historically, modern retreat of i-prosthesis before word initial /s/+C (e.g. miþ isforza “with effort” has generally given way to miþ sforzȧ) suggests that the structure is now underdetermined, with occurrence of /s.C/ or /.sC/ variable “according to the context and the idiosyncratic behaviour of the speakers.”

CCC

- /s/ + voiceless stop or /f/ + /ɾ/;

- /z/ + voiced stop + /ɾ/;

- /s/ + /p k/ + /l/;

- /z/ + /b/ + /l/;

- /f v/ or any stop + /ɾ/ + /j w/.

| V₁ | V₂ | V₃ |

|---|---|---|

| a ɐ e ɛ | i [j] u [w] | — |

| o ɔ | i [j] | — |

| i [j] | e o | — |

| i [j] | ɐ ɛ ɔ | i [j] |

| i [j] | u [w] | o |

| u [w] | ɐ ɛ ɔ | i [j] |

| u [w] | e o | — |

| u [w] | i | — |

The nucleus is the only mandatory part of a syllable and must be a vowel or a diphthong. In a falling diphthong the most common second elements are /i̯/ or /u̯/. Combinations of /j w/ with vowels are often labelled diphthongs, allowing for combinations of /j w/ with falling diphthongs to be called triphthongs. One view holds that it is more accurate to label /j w/ as consonants and /jV wV/ as consonant-vowel sequences rather than rising diphthongs. In that interpretation, Luthic has only falling diphthongs (phonemically at least, cf. Synaeresis) and no triphthongs.

| C₁ | C₂ |

|---|---|

| m n l ɾ | Cₓ |

| Cₓ | — |

Luthic permits a small number of coda consonants. Outside of loanwords, the permitted consonants are:

- The first element of any geminate.

- A nasal consonant that is either /n/ (word-finally) or one that is homorganic to a following consonant.

- /ɾ/ and /l/.

- /s/ (though not before fricatives).

Prosody

Luthic is quasi-paroxytonic, meaning that most words receive stress on their penultimate (second-to-last) syllable. Monosyllabic words tend to lack stress in their only syllable, unless emphasised or accentuated. Enclitic and other unstressed personal pronouns do not affect stress patterns. Some monosyllabic words may have natural stress (even if not emphasised), but it is weaker than those in polysyllabic words.

- rasda (ʀᴀ-sda ~ ʀᴀs-da) /ˈʁa.zdɐ ~ ˈʁaz.dɐ/;

- Italia (i-ᴛᴀ-lia) /iˈta.ljɐ];

- approssimativamente (ap-pros-si-ma-ti-va-ᴍᴇɴ-te) /ɐp.pɾos.si.mɐ.θi.vɐˈmen.te/.

Compound words have secondary stress on their penultimate syllable. Some suffixes also maintain the suffixed word secondary stress.

- panzar + campo + vaġno > panzarcampovaġno (ᴘᴀɴ-zar-ᴄᴀᴍ-po-ᴠᴀ-ġno) /ˌpan.t͡sɐɾˌkam.poˈvaɲ.ɲu/;

- broþar + -scape > broþarscape (ʙʀᴏ-þar-sᴄᴀ-pe) /ˌbɾo.θɐɾˈska.fe/.

Secondary stress is however often omitted by Italian influence. Tetrasyllabic (and beyond) words may have a very weak secondary stress in the fourth-to-last syllable (i.e. two syllables before the main or primary stress).

Research

Luthic is a well-studied language, and multiple universities in Italy have departments devoted to Luthic or linguistics with active research projects on the language, mainly in Ravenna, such as the Linguistic Circle of Ravenna (Luthic: Creizzo Rasdavitascapetico Ravennai; Italian: Circolo Linguistico di Ravenna) at Ravenna University, and there are many dictionaries and technological resources on the language. The language council Gafaurdo faul·la Rasda Lûthica also publishes research on the language both nationally and internationally. Academic descriptions of the language are published both in Luthic, Italian and English. The most complete grammar is the Grammatica ġli Lûthicai Rasdai (Grammar of the Luthic Language) by Alessandro Fiscar & Luca Vaġnar, and it is written in Luthic and contains over 800 pages.

Multiple corpora of Luthic language data are available. The Luthic Online Dictionary project provides a curated corpus of 35,000 words.

History

The Ravenna School of Linguistics evolved around Giovanni Laggobardi and his developing theory of language in linguistic structuralism. Together with Soġnafreþo Rossi he founded the Circle of Linguistics of Ravenna in 1964, a group of linguists based on the model of the Prague Linguistic Circle. From 1970, Ravenna University offered courses in languages and philosophy but the students were unable to finish their studies without going to Accademia della Crusca for their final examinations.

Ravenna University Circle of Phonological Development (Luthic: Creizzo Sviluppi Phonologici giȧ Accademiȧ Ravennȧ) was developed in 1990, however very little research has been done on the earliest stages of phonological development in Luthic.

Ravenna University Circle of Theology (Luthic: Creizzo Theologiai giȧ Accademiȧ Ravennȧ) was developed in 2000 in association with the Ravenna Cathedral or Metropolitan Cathedral of the Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ (Luthic: Cathedrale metropolitana deï Osstassi Unsari Signori Gesosi Christi; Italian: Cattedrale metropolitana della Risurrezione di Nostro Signore Gesù Cristo; Duomo di Ravenna).

Aina lettura essenziale summȧ importanzȧ, inu andarogiugga.

“An essential lecture, of the highest importance, without equivalents.”

The Handbook of Luthic Linguistics, Culture and Religion

In 2012, a collaboration of the Circle of Linguistics, the Circle of Phonological Development and the Circle of Theology resulted in The Handbook of Luthic Linguistics, Culture and Religion (Luthic: Il Handobuoco Rasdavitascapeticai, Colturai e Religioni Luthicai) initiated in 2005 by Lucia Giamane, designed to illuminate an area of knowledge that encompasses both general linguistics and specialised, philologically oriented linguistics as well as those fields of science that have developed in recent decades from the increasingly extensive research into the diverse phenomena of communicative action.

Grammar

Luthic grammar is almost typical of the grammar of Romance languages in general. Cases exist for personal pronouns (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), and unlike other Romance languages (except Romanian), they also exist for nouns, but are often ignored in common speech, mainly because of the Italian influence, a language who lacks noun cases. There are three basic classes of nouns in Luthic, referred to as genders, masculine, feminine and neuter. Masculine nouns typically end in -o, with plural marked by -i, feminine nouns typically end in -a, with plural marked by -ai, and neuter nouns typically end in -ȯ, with plural marked by -a. A fourth category of nouns is unmarked for gender, ending in -e in the singular and -i in the plural; a variant of the unmarked declension is found ending in -r in the singular and -i in the plural, it lacks neuter nouns:

Examples:

| Definition | Gender | Singular nominative | Plural nominative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Son | Masculine | Fiġlo | Fiġli |

| Flower | Feminine | Bloma | Blomai |

| Fruit | Neuter | Acranȯ | Acrana |

| Love | Masculine | Amore | Amori |

| Art | Feminine | Crafte | Crafti |

| Water | Neuter | Vadne | Vadni |

| King | Masculine | Regġe | Regġi |

| Heart | Neuter | Hairtene | Hairteni |

| Father | Masculine | Fadar | Fadari |

| Mother | Feminine | Modar | Modari |

Declension paradigm in formal Standard Luthic:

| Number | Case | o-stem m | a-stem f | o-stem n | i-stem unm | r-stem unm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | nom. | dago | geva | hauviþȯ | crafte | broþar |

| acc. | dagȯ | geva | hauviþȯ | crafte | broþare | |

| dat. | dagȧ | gevȧ | hauviþȧ | crafti | broþari | |

| gen. | dagi | gevai | hauviþi | crafti | broþari | |

| Plural | nom. | dagi | gevai | hauviþa | crafti | broþari |

| acc. | dagos | gevas | hauviþa | craftes | broþares | |

| dat. | dagom | gevam | hauviþom | craftivo | broþarivo | |

| gen. | dagoro | gevaro | hauviþoro | craftem | broþarem |

Pronouns

Luthic, like Latin and Gothic, inherited the full set of Indo-European pronouns: personal pronouns (including reflexive pronouns for each of the three grammatical persons), possessive pronouns, both simple and compound demonstratives, relative pronouns, interrogatives and indefinite pronouns. Each follows a particular pattern of inflection (partially mirroring the noun declension), much like other Indo-European languages. Although Luthic inherited a paradigm extremely close to Gothic (and Common Germanic), the Italic influence is visible in the genitive and plural formations.

| PIE | Latin | Gothic | German | Luthic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *u̯ei̯ nom, *n̥s acc | nōs nom/acc | weis nom, uns acc | wir nom, uns acc | vi nom, unse acc |

| Number | Case | 1st person | 2st person | 3rd person | reflexive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | |||||

| Singular | nom. | ic | þû | is | ia | ata | — |

| acc. | mic | þuc | inȯ | ina | ata | sic | |

| dat. | mis | þus | iȧ | iȧ | iȧ | sis | |

| dat. | meina | þeina | eis | isai | eis | seina | |

| Singular | nom. | vi | gi | eis | isai | ia | — |

| acc. | unse | isve | eis | isas | ia | sic | |

| dat. | unsis | isvis | eis | eis | eis | sis | |

| gen. | unsara | isvara | eisôro | eisâro | eisôro | seina | |

| Number | Case | 1st person singular | 2st person singular | 3rd person singular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | meino | meina | meinȯ | þeino | þeina | þeinȯ | seino | seina | seinȯ |

| acc. | meinȯ | meina | meinȯ | þeinȯ | þeina | þeinȯ | seinȯ | seina | seinȯ | |

| dat. | meinȧ | meinȧ | meinȧ | þeinȧ | þeinȧ | þeinȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | |

| gen. | meini | meinai | meini | þeini | þeinai | þeini | seini | seinai | seini | |

| Plural | nom. | meini | meinai | meina | þeini | þeinai | þeina | seini | seinai | seina |

| acc. | meinos | meinas | meina | þeinos | þeinas | þeina | seinos | seinas | seina | |

| dat. | meinom | meinam | meinom | þeinom | þeinam | þeinom | seinom | seinam | seinom | |

| gen. | meinoro | meinaro | meinoro | þeinoro | þeinaro | þeinoro | seinoro | seinaro | seinoro | |

| Number | Case | 1st person singular | 2st person singular | 3rd person singular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | unsar | unsara | unsarȯ | isvar | isvara | isvarȯ | seino | seina | seinȯ |

| acc. | unsare | unsara | unsarȯ | isvare | isvara | isvarȯ | seinȯ | seina | seinȯ | |

| dat. | unsari | unsarȧ | unsarȧ | isvari | isvarȧ | isvarȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | |

| gen. | unsari | unsarai | unsari | isvari | isvarai | isvari | seini | seinai | seini | |

| Plural | nom. | unsari | unsarai | unsara | isvari | isvarai | isvara | seini | seinai | seina |

| acc. | unsares | unsaras | unsara | isvares | isvaras | isvara | seinos | seinas | seina | |

| dat. | unsarivo | unsaram | unsarom | isvarivo | isvaram | isvarom | seinom | seinam | seinom | |

| gen. | unsarem | unsararo | unsaroro | isvarem | isvararo | isvaroro | seinoro | seinaro | seinoro | |

The pronouns unsar, isvar have an irregular declension, being declined like an unmarked adjective in the masculine gender and marked in the other genders. Every possessive pronoun is declined like an o-stem adjective for masculine and neuter gender, while its feminine counterpart is declined as an a-stem adjective

Interrogative and indefinite pronouns are indeclinable by case and number:

| Interrogative pronouns | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|---|

| What | ce | ce | ce |

| Who | qo | qa | qȯ |

| Whom | ci | ci | ci |

| Which | carge | carge | carge |

| Whose | cogio | cogia | cogiȯ |

| Indefinite pronouns | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Each | caso | casa | casȯ |

| Every | cargiso | cargisa | cargisȯ |

| Whoever/Whatever | þecargiso | þecargisa | þecargisȯ |

The relative pronoun ei is fully indeclinable, it is sometimes called “common relative particle”.

Luthic has a Proximal-Medial-Distal demonstrative system:

| Number | Case | Proximal | Medial | Distal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | so | sa | þata | este | esta | estȯ | giaino | giaina | giainȯ |

| acc. | þȯ | þa | þata | este | esta | estȯ | giainȯ | giaina | giainȯ | |

| dat. | þammo | þisai | þammo | esti | estȧ | estȧ | giainȧ | giainȧ | giainȧ | |

| gen. | þis | þisai | þis | estis | estai | esti | giaini | giainai | giaini | |

| Plural | nom. | þi | þai | þa | esti | estai | esta | giaini | giainai | giaina |

| acc. | þos | þas | þa | estes | estas | esta | giainos | giainas | giaina | |

| dat. | þom | þam | þom | estivo | estam | estom | giainom | giainam | giainom | |

| gen. | þisaro | þisara | þisaro | estem | estaro | estoro | giainoro | giainaro | giainoro | |

Articles

Luthic articles are used similarly to the English articles, a and the. However, they are declined differently according to the number, gender and case of their nouns.

| Number | Case | Indefinite | Definite | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | aino | aina | ainȯ | il | la | lata, ata |

| acc. | ainȯ | aina | ainȯ | lȯ | la | lata, ata | |

| dat. | ainȧ | ainȧ | ainȧ | lȧ | lȧ | lȧ | |

| gen. | aini | ainai | aini | ġli, i | ġli, i | ġli, i | |

| Plural | nom. | aini | ainai | aina | ġli, i | lai | la |

| acc. | ainos | ainas | aina | los | las | la | |

| dat. | ainom | ainam | ainom | lom | lam | lom | |

| gen. | ainoro | ainaro | ainoro | loro | loro | loro | |

Adjectives

In Luthic, an adjective can be placed before or after the noun. The unmarked placement for most adjectives is after the noun. Placing the adjective after the noun can alter its meaning or indicate restrictiveness of reference.

- Aino buoco rosso “a red book” (unmarked)

- Aino rosso buoco “a book that is red” (marked)

Adjectives are inflected for case, gender and number, the paradigmata are identical to the nominal paradigmata.

| Number | Case | o-stem m | a-stem f | o-stem n | i-stem unm | r-stem unm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | nom. | rosso | rossa | rossȯ | felice | polchar |

| acc. | rossȯ | rossa | rossȯ | felice | polchare | |

| dat. | rossȧ | rossȧ | rossȧ | felici | polchari | |

| gen. | rossi | rossai | rossi | felici | polchari | |

| Plural | nom. | rossi | rossai | rossa | felici | polchari |

| acc. | rossos | rossas | rossa | felices | polchares | |

| dat. | rossom | rossam | rossom | felicivo | polcharivo | |

| gen. | rossoro | rossaro | rossoro | felicem | polcharem |

Luthic has two grammatical constructions for expressing comparison: comparative and superlative. The suffixes -izo (the “comparative”) and -issimo (the “superlative”) are of Indo-European origin and are cognate with the Latin suffixes -ior and -issimus and Ancient Greek -ῑ́ων (-īōn) and -ῐστος (-istos). This system also contains a number of irregular forms, mainly because of suppletion.

Regular examples are:

- rosso “red” > rossizo “redder”

- rosso “red” > rossissimo “reddest”

- polchar “beautiful” > polcharizo “more beautiful”

- polchar “beautiful” > polcharissimo “most beautiful”

Irregular examples are:

- buono “good” > betizo “better”

- buono “good” > betissimo “best”

- malo “bad” > vairsizo “worse”

- malo “bad” > vairsissimo “worst”

| Number | Case | o-stem m | a-stem f | o-stem n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | nom. | -izo | -iza | -izȯ |

| acc. | -izȯ | -iza | -izȯ | |

| dat. | -izȧ | -izȧ | -izȧ | |

| gen. | -izi | -izai | -izi | |

| Plural | nom. | -izi | -izai | -iza |

| acc. | -izos | -izas | -iza | |

| dat. | -izom | -izam | -izom | |

| gen. | -izoro | -izaro | -izoro |

| Number | Case | o-stem m | a-stem f | o-stem n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | nom. | -issimo | -issima | -issimȯ |

| acc. | -issimȯ | -issima | -issimȯ | |

| dat. | -issimȧ | -issimȧ | -issimȧ | |

| gen. | -issimi | -issimai | -issimi | |

| Plural | nom. | -issimi | -issimai | -issima |

| acc. | -issimos | -issimas | -issima | |

| dat. | -issimom | -issimam | -issimom | |

| gen. | -issimoro | -issimaro | -issimoro |

Numerals

| # | Cardinal | Ordinal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word | Declension | Word | Declension | |

| 1 | aino | o-stem adjective | fromo | o-stem adjetive |

| 2 | tvi | o-stem adjective, plurale tantum | anþar | r-stem adjetive |

| 3 | þreis | indeclinable | þrigiane | i-stem adjetive |

| 4 | fidvor | indeclinable | fidvorêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 5 | fimfe | indeclinable | fimfêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 6 | sê | indeclinable | sesto | o-stem adjective |

| 7 | siu | indeclinable | siudo | o-stem adjective |

| 8 | ahtau | indeclinable | ahtudo | o-stem adjective |

| 9 | niu | indeclinable | niudo | o-stem adjective |

| 10 | ziu | indeclinable | ziudo | o-stem adjective |

| 11 | aillefe | indeclinable | aillefto | o-stem adjective |

| 12 | tvelefe | indeclinable | tvelefto | o-stem adjective |

| 13 | þreiziu | indeclinable | þreiziudo | o-stem adjective |

| 14 | fidvorziu | indeclinable | fidvorziudo | o-stem adjective |

| 15 | fimfeziu | indeclinable | fimfeziudo | o-stem adjective |

| 16 | seziu | indeclinable | seziudo | o-stem adjective |

| 17 | setteziu | indeclinable | setteziudo | o-stem adjective |

| 18 | tvedivinta | indeclinable | tvedivintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 19 | aindivinta | indeclinable | aindivintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 20 | vinta | indeclinable | vintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 28 | tvediþreinta | indeclinable | tvediþreintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 29 | aindiþreinta | indeclinable | aindiþreintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 30 | þreinta | indeclinable | þreintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 38 | tvedifidvorinta | indeclinable | tvedifidvorintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 39 | aindifidvorinta | indeclinable | aindifidvorintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 40 | fidvorinta | indeclinable | fidvorintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 50 | fimfinta | indeclinable | fimfintêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 60 | sessanta | indeclinable | sessantêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 70 | siunta | indeclinable | siuntêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 80 | ahtanta | indeclinable | ahtantêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 90 | niunta | indeclinable | niuntêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 98 | tvedihondo | o-stem adjective | tvedihondêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 99 | aindihondo | o-stem adjective | aindihondêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 100 | hondo | o-stem adjective | hondêsimo | o-stem adjective |

- Adverbial numbers are formed together with the noun vece: aina vece “once”, tvai veci “twice”.

- Multiplier numbers are formed together with the noun falþo: aino falþo “single, onefold”, hondi falþi “centuple, hundredfold”. This noun was originally a suffix, compare Gothic 𐌰𐌹𐌽𐍆𐌰𐌻𐌸𐍃 (ainfalþs), English onefold, Icelandic einfaldur.

- Distributive numbers are formed together with the adjective falþoleico: þreis falþoleici “triply”.

- Collective numbers are formed together with the adjective somo: tvelefe somi “dozen”.

- Fractional numbers are formed together with the adjective integro: fidvor integri “quarter”.

| # | Cardinal | Ordinal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word | Declension | Word | Declension | |

| 200 | tvihondi α | o-stem adjective, plurale tantum | tvihondêsimo β | o-stem adjective |

| 500 | fimfehondi γ | o-stem adjective, plurale tantum | fimfehondêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 1 000 | mille | i-stem | millêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 2 000 | tvimilli α | i-stem adjective, plurale tantum | tvimillêsimo β | o-stem adjective |

| 5 000 | fimfemilli γ | i-stem adjective, plurale tantum | fimfemillêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 10 000 | ziumilli γ | i-stem adjective, plurale tantum | ziumillêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 20 000 | vintamilli γ | i-stem adjective, plurale tantum | vintamillêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 50 000 | fimfintamilli γ | i-stem adjective, plurale tantum | fimfintamillêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 100 000 | hondimilli α | i-stem adjective, plurale tantum | hondimillêsimo β | o-stem adjective |

| 200 000 | tvihondimilli δ | i-stem adjective, plurale tantum | tvihondimillêsimo β | o-stem adjective |

| 500 000 | fimfehondimilli ε | i-stem adjective, plurale tantum | fimfehondimillêsimo β | o-stem adjective |

| 106 | millione | i-stem adjective | millionêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 2 x 106 | tvimillioni α | i-stem adjective, plurale tantum | tvimillionêsimo β | o-stem adjective |

| 109 | milliarde | i-stem adjective | milliardêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 1012 | billione | i-stem adjective | billionêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 1015 | billiarde | i-stem adjective | billiardêsimo | o-stem adjective |

| 1019 | trillione | i-stem adjective | trillionêsimo | o-stem adjective |

- α Both elements are declinable, e.g. tvaihondai, tvahonda;

- β Only the last element is declinable, e.g. tvihondêsima, tvihondêsimoro;

- γ The first element is indeclinable;

- δ All the three elements are declinable, e.g. tvarohondaromillem, tvoshondosmilles;

- ε Only the two last elements are declinable, e.g. fimfehondommillivo.

Luthic uses the long scale, unlike English that uses the short scale instead. The long and short scales are two of several naming systems for integer powers of ten which use some of the same terms for different magnitudes. Luthic has a verbal system similar to Italian, German, Dutch and French:

| Luthic | Italian | German | Dutch | French | English | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 106 | millione | milione | Million | miljoen | million | million |

| 109 | milliarde | miliardo | Milliarde | miljard | milliard | billion |

| 1012 | billione | bilione | Billion | biljoen | billion | trillion |

Combinations of a decade and a unit are constructed in a regular way: the decade comes first followed by the unit. No spaces are written between them. Vowel collision triggers an interpunct. For example:

- 28 vinta·ahtau (lit “twenty eight”)

- 73 siuntaþreis (lit “seventy three”)

- 82 ahtantatvi (lit “eighty two”)

- 95 niuntafimfe (lit “ninety five”)

Combinations of a hundred and a lower number are expressed by just placing them together, with the hundred coming first.

- 111 hondoaillefe

- 164 hondosessantafidvor

- 225 tvihondivintafimfe

- 788 siuhondi·ahtanta·ahtau

Combinations of a thousand and a lower number are expressed by placing them together, with the thousand coming first. A space is written between them.

- 1 066 mille sessantasê

- 9 011 niumilli aillefe

- 61 500 sessanta·ainomilli fimfehondi

- 123 456 hondivintaþreismilli fidvorhondifimfintasê

For millions and above, combinations with lower numbers are much the same as with the thousands.

- 123 456 789 hondivintaþreis millioni fidvorhondifimfintasêhondi siuhondiniunta·ahtau

- 10 987 654 321 ziu milliardi niuhondi·ahtantasiumillioni sehondifimfintafidvorhondi þreishondivinta·aino

When alone, numbers are always in the masculine gender, however numbers always agree in gender and in case (if declinable) with the head noun. For example:

- aino vaire (“one man”)

- aina qena (“one woman”)

- aino harge hondom vairivo (“an army [composed] of hundred men”)

- il meino hareme hâþ tvashondas qenas (“my harem has two hundred women”)

Compound numbers have both elements declined (if possible):

| Number | Case | o-stem m | a-stem f | o-stem n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plural | nom. | tvihondi | tvaihondai | tvahonda |

| acc. | tvoshondos | tvashondas | tvahonda | |

| dat. | tvomhondom | tvamhondam | tvomhondom | |

| gen. | tvorohondoro | tvarohondaro | tvorohondoro |

Verbs

Luthic verbs have a high degree of inflection, the majority of which follows one of three common patterns of conjugation. Luthic conjugation is affected by voice, mood, person, tense, number, aspect and occasionally gender.

The four classes of verbs (conjugation’s patterns) are distinguished by the infinitive’s endings form of the verb:

- 1st conjugation: -are (þagcare “to think”);

- 2nd conjugation: -ere (credere “to believe”);

- 3rd conjugation: -ore (holore “to accuse”);

- 4th conjugation: -ire (dormire “to sleep”).

Additionally, Luthic has a number of verbs that do not follow predictable patterns in all conjugation classes, most markedly the present and the past. Often classified together as irregular verbs, their irregularities occur to different degrees, with forms of vessare “to be”, and somewhat less extremely, havere “to have”, the least predictable. Others, such as ganare “to go”, stare “to stay, to stand”, taugiare “to do, to make”, and numerous others, follow various degrees of regularity within paradigms, largely due to suppletion, historical sound change or analogical developments.

Present

The present is used for:

- Events happening in the present;

- Habitual actions;

- Current states of being and conditions;

- Actions planned to occur in the future.

| þagcare | credere | holore | dormire | vessare | havere | ganare | stare | taugiare | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ic | þagcȯ | credȯ | holȯ | dormȯ | im | hô | gô | stô | taugiȯ |

| þû | þagcas | credes | holos | dormis | is | haïs | gâs | staïs | taugis |

| is | þagcat | credet | holot | dormit | ist | hâþ | gâþ | stâþ | taugit |

| vi | þagcamos | credemos | holomos | dormimos | ismos | haimos | gamos | stamos | taugiamos |

| gi | þagcates | credetes | holotos | dormites | istes | haites | gates | states | taugiates |

| eis | þagcanno | credonno | holonno | dormonno | sonno | hanno | ganno | stonno | taugionno |

| þagcare | credere | holore | dormire | vessare | havere | ganare | stare | taugiare | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ic | þagcara | credera | holora | dormira | — | havara | andara | — | taugiara |

| þû | þagcaa | credesa | holosa | dormisa | — | havasa | andasa | — | taugiasa |

| is | þagcada | crededa | holoda | dormida | — | havada | andada | stada | taugiada |

| vi | þagcanda | credenda | holonda | dorminda | — | havanda | andanda | — | taugianda |

| gi | þagcanda | credenda | holonda | dorminda | — | havanda | andanda | — | taugianda |

| eis | þagcanda | credenda | holonda | dorminda | — | havanda | andanda | standa | taugianda |

Present subjunctive

Used for subordinate clauses of the present to express opinion, possibility, desire, or doubt. The Subjunctive is almost always preceded by the common relative particle.

| þagcare | credere | holore | dormire | vessare | havere | ganare | stare | taugiare | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ic | þagci | creda | holuȯ | dorma | sia | abbia | vada | stia | taugia |

| þû | þagcis | credas | holuas | dormas | sias | abbias | vadas | stias | taugias |

| is | þagcit | credat | holuat | dormat | siaþ | abbiat | vadat | stiaþ | taugiat |

| vi | þagciamos | crediamos | holuamos | dormamos | siamos | abbiamos | andiamos | stiamos | taugiaumos |

| gi | þagciates | crediates | holuates | dormates | siates | abbiates | andiates | stiates | taugiautes |

| eis | þagcinno | credanno | holanno | dormanno | sianno | abbianno | vadanno | stianno | taugianno |

| þagcare | credere | holore | dormire | vessare | havere | ganare | stare | taugiare | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ic | þagcira | credara | holuora | dormara | — | abbaira | vadara | — | taugiaura |

| þû | þagcisa | credasa | holuasa | dormasa | — | abbaisa | vadasa | — | taugiausa |

| is | þagcida | credada | holuada | dormada | — | abbaida | vadada | stiada | taugiauda |

| vi | þagcinda | credianda | holuonda | dormanda | — | abbainda | andianda | — | taugiaunda |

| gi | þagcinda | credianda | holuonda | dormanda | — | abbainda | andianda | — | taugiaunda |

| eis | þagcinda | credianda | holuonda | dormanda | — | abbainda | andianda | stianda | taugiaunda |

Present conditional

Used for events that are dependent upon another event occurring. The conditional is also used for politely asking for something (as in English: “could I please have a glass of water?”)

| þagcare | credere | holore | dormire | vessare | havere | ganare | stare | taugiare | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ic | þagceria | crederia | holoria | dormiria | saria | haveria | garia | staria | tavaria |

| þû | þagcerias | crederias | holorias | dormirias | sarias | haverias | garias | starias | tavarias |

| is | þagceriat | crederiat | holoriat | dormiriat | sariat | haveriat | gariat | stariat | taveriat |

| vi | þagceriamos | crederiamos | holoriamos | dormiriamos | sariamos | haveriamos | gariamos | stariamos | tavariamos |

| gi | þagceriates | crederiates | holoriates | dormiriates | sariates | haveriates | gariates | stariates | tavariates |

| eis | þagcerianno | crederianno | holorianno | dormirianno | sarianno | haverianno | garianno | starianno | tavarianno |

| þagcare | credere | holore | dormire | vessare | havere | ganare | stare | taugiare | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ic | þagceriara | crederiara | holoriara | dormiriara | — | haveriara | gariara | — | tavariara |

| þû | þagceriasa | crederiasa | holoriasa | dormiriasa | — | haveriasa | gariasa | — | tavariasa |

| is | þagceriada | crederiada | holoriada | dormiriada | — | haveriada | gariada | stariada | taveriada |

| vi | þagcerianda | crederianda | holorianda | dormirianda | — | haverianda | garianda | — | tavarianda |

| gi | þagcerianda | crederianda | holorianda | dormirianda | — | haverianda | garianda | — | tavarianda |

| eis | þagcerianda | crederianda | holorianda | dormirianda | — | haverianda | garianda | starianda | tavarianda |

- vessare lacks a passive voice form;

- stare passive voice form is only impersonal.

Present perfect

The present perfect is used for single actions or events (sa maurgina im ganato a scuola “I went to school this morning”), or change in state (sic ist þvairsoto can ata iȧ hô rogiato “he got angry when I told him that”), contrasting with the imperfect which is used for habits (egġiavȯ biciclettȧ a scuola alla maurgina “I used to go to school by bike every morning”), or repeated actions, not happening at a specific time (sic þvairsovat alla vece ei, giuvedar can ata iȧ rogiavat “he got angry every time someone told him that”).

Past participle

The past participle is used to form the compound pasts (e.g. hô tavito “I have done”). Regular verbs follow a predictable pattern, but there are many verbs with an irregular past participle.

- 1st conjugation: -ato (þagcato “thought”);

- 2nd conjugation: -uto (creduto “believed”);

- 3rd conjugation: -oto (holoto “accused”);

- 4th conjugation: -ito (dormito “slept”);

- vessare and stare have both stato;

- qemare (“to come”) has qemuto;

- taugiare has tavito.

Vocabulary

It is generally stated that Luthic has around 370,000 words, or 410,000 if obsolete words are counted, however 98% of the Luthic used today consists of only 5,800 words.

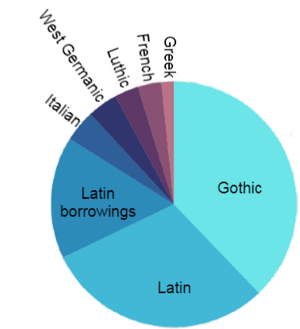

A 2016 statistic by Lucia Giamane is based on 3,172 words chosen on the criteria of frequency, semantic richness and productivity, which also contain words formed on the territory of the Luthic language. This statistic gives the percentages below:

- 1,200 words inherited from Gothic;

- 953 words inherited from Latin;

- 510 words, academic loanwords from Latin;

- 133 words borrowed from Italian;

- 125 words borrowed from West Germanic, such as Frankish, Langobardic and Standard High German;

- 101 words formed in Luthic;

- 98 words borrowed from French;

- 52 words borrowed from Greek.

Luthic has approximately 2,000 uncompounded words inherited from Proto-Indo-European. These were inherited via:

- 45% Germanic;

- 43% Italic, Romance;

- 8% Celtic;

- 2% Hellenic;

- 2% Uncertain.

Sample text

The North Wind and the Sun in Luthic:

- Orthographic version in Luthic

- Il vendo trabairganȧ ed ata sauilȯ giucavanno carge erat il fortizo, can aino pellegrino qemavat avvolto hacolȧ varmȧ ana. I tvi dicideronno ei il fromo a rimuovere lȯ hacolȯ pellegrinȧ sariat il fortizo anþerȧ. Il vendo trabairganȧ dustogġiat a soffiare violenzȧ, ac ata maize is soffiavat, ata maize il pellegrino striggevat hacolȯ; tanto ei al·lȯ angiȯ il vendo desistait dȧ seinȧ sforzȧ. Ata sauilȯ allora sceinaut varmamente nal·lȯ hemenȯ, e þan il pellegrino rimuovait lȯ hacolȯ immediatamente. Þan il vendo trabairganȧ obbligauda ad andahaitare ei lata sauilȯ erat ata fortizȯ tvoro.

- Broad transcription

- /il ˈven.du tɾɐˈbɛɾ.ɡɐ.na e.d‿ɐ.tɐ ˈsɔj.lo d͡ʒu.kɐˈvɐ̃.nu kɐɾ.d͡ʒe ˈɛ.ɾɐθ il ˈfɔɾ.ti.d͡zu | kɐn ɛ.nu pel.leˈɡɾi.nu kʷeˈma.vɐθ avˈvol.tu hɐˈkɔ.la ˈvaɾ.ma a.nɐ ‖ i tvi di.t͡ʃi.deˈʁõ.nu ˈi | il ˈfɾo.mu ɐ ʁi.mwoˈve.ɾe lo hɐˈkɔ.lo pel.leˈɡɾi.na ˈsa.ɾjɐθ il ˈfɔɾ.ti.d͡zu ɐ̃ˈθe.ɾa ‖ il ˈven.du tɾɐˈbɛɾ.ɡɐ.na duˈstɔd.d͡ʒɐθ ɐ sofˈfja.ɾe vjoˈlɛn.t͡sa | a.k‿ɐ.tɐ ˈmɛ.d͡ze is sofˈfja.vɐθ | a.tɐ ˈmɛ.d͡ze il pel.leˈɡɾi.nu stɾiŋˈɡe.vɐθ hɐˈkɔ.lo | ˈtan.tu ˈi al.lo ˈan.d͡ʒo il ˈven.du deˈzi.stɛθ da ˈsi.na ˈsfɔɾ.t͡sa ‖ a.tɐ ˈsɔj.lo alˈlɔ.ɾɐ ʃiˈnɔθ vɐɾ.mɐˈmen.te nal.lo heˈme.no | e θɐn il pel.leˈɡɾi.nu ʁiˈmwo.vɛθ lo hɐˈkɔ.lo ĩ.me.djɐ.tɐˈmen.te ‖ θɐn il ˈven.du tɾɐˈbɛɾ.ɡɐ.na ob.bliˈɡɔ.dɐ a.d‿ɐn.da.hɛˈta.ɾe ˈi | lɐ.tɐ ˈsɔj.lo ˈɛ.ɾɐθ a.tɐ ˈfɔɾ.ti.d͡zo ˈtvo.ɾu/

- Narrow transcription (differences emphasised)

- [il ˈven.du tɾɐˈbɛɾ.ɣ˕ɐ.na e.ð‿ɐ.θɐ' ˈsɔj.lo d͡ʒu.xɐˈvɐ̃.nu kɐɾ.d͡ʒe ˈɛ.ɾɐθ il ˈfɔɾ.ti.d͡zu | kɐn ɛ.nu pel.leˈɡɾi.nu kᶣeˈma.vɐθ avˈvol.tu hɐˈkɔ.la ˈvaɾ.ma a.nɐ ‖ i tvi di.t͡ʃi.ð̞eˈʁõ.nu ˈi | il ˈfɾo.mu ɐ‿ʀi.mwoˈve.ɾe lo hɐˈkɔ.lo pel.leˈɡɾi.na ˈsa.ɾjɐθ il ˈfɔɾ.ti.d͡zu ɐ̃ˈt͡θe.ɾa ‖ il ˈven.du tɾɐˈbɛɾ.ɣ˕ɐ.na duˈstɔd.d͡ʒɐθ ɐs‿sofˈfja.ɾe vjoˈlɛn.t͡sa | a.x‿ɐ.θɐ ˈmɛ.d͡ze is sofˈfja.vɐθ | a.θɐ ˈmɛ.d͡ze il pel.leˈɡɾi.nu stɾiŋˈɡ̟e.vɐh‿hɐˈkɔ.lo | ˈtan.tu ˈi al.lo ˈan.d͡ʒo il ˈven.du deˈzis.tɛθ da‿sˈsi.na ˈsfɔɾ.t͡sa ‖ a.θɐ ˈsɔj.lo alˈlɔ.ɾɐ ʃiˈnɔθ vɐɾ.mɐˈmen.te nal.lo heˈme.no | e θɐn il pel.leˈɡɾi.nu ʁiˈmwo.vɛθ lo hɐˈkɔ.lo ĩ.me.djɐ.θɐˈmen.te ‖ θɐn il ˈven.du tɾɐˈbɛɾ.ɣ˕ɐ.na ob.bliˈɡɔ.ð̞ɐ a.ð‿ɐn.da.hɛˈta.ɾe ˈi | lɐ.θɐ ˈsɔj.lo ˈɛ.ɾɐθ a.θɐ ˈfɔɾ.ti.d͡zo ˈtvo.ɾu]

- Orthographic version in English

- The North Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger, when a traveller came along wrapped in a warm cloak. They agreed that the one who first succeeded in making the traveller take his cloak off should be considered stronger than the other. Then the North Wind blew as hard as he could, but the more he blew the more closely did the traveller fold his cloak around him; and at last the North Wind gave up the attempt. Then the Sun shined out warmly, and immediately the traveller took off his cloak. And so the North Wind was obliged to confess that the Sun was the stronger of the two.

Bibliography

- Tagliavini, Carlo (1948). Le origini delle lingue Neolatine: corso introduttivo di filologia romanza. Bologna: Pàtron.

- Haller, Hermann W. (1999). The other Italy: the literary canon in dialect. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Renzi, Lorenzo (1994). Nuova introduzione alla filologia romanza. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Ringe, Donald A. (2006). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. Linguistic history of English, v. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kroonen, Guus (2013). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Leiden–Boston: Brill.

- Orel, Vladimir (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Leiden–Boston: Brill.

- Kloekhorst, Alwin (2008). Etymological Dictionary of the Hittite Inherited Lexicon. Leiden–Boston: Brill.

- de Vaan, Michiel (2008). Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the other Italic Languages. Leiden–Boston: Brill.

- Bennett, William Holmes (1980). An Introduction to the Gothic Language. New York: Modern Language Association of America.

- Wright, Joseph (1910). Grammar of the Gothic Language. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Snædal, Magnús (2011). "Gothic <ggw>". Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis. 128: 145–154.

- G. H. Balg (1889): A comparative glossary of the Gothic language with especial reference to English and German. New York: Westermann & Company.

- Ebbinghaus, E. A. (1976). THE FIRST ENTRY OF THE GOTHIC CALENDAR. The Journal of Theological Studies, 27(1), 140–145. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Voyles, Joseph B. (1992). Early Germanic Grammar. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Sihler, Andrew L. (1995). New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Holt, D. Eric (2016). From Latin to Portuguese: Main Phonological Changes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Grandgent, C. H. (1927). From Latin to Italian: An Historical Outline of the Phonology and Morphology of the Italian Language. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Grandgent, C. H. (1907). An introduction to Vulgar Latin. Boston: D.C. Heath & Co.

- Ferguson, Thaddeus (1976). A history of the Romance vowel systems through paradigmatic reconstruction. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Bruckner, Wilhelm (1895). Die Sprache der Langobarden. Quellen und Forschungen zur Sprach- und Culturgeschichte der germanischen Völker. Vol. LXXV. Strassburg: Trübner.

- Gamillscheg, Ernst (2017) [First published 1935]. Die Ostgoten. Die Langobarden. Die altgermanischen Bestandteile des Ostromanischen. Altgermanisches im Alpenromanischen. Romania Germanica. Vol. 2. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Guitel, Geneviève (1975). Histoire comparée des numérations écrites. Paris: Flammarion.

- Gvozdanovic, Jadranka (1991). Indo-European Numerals. Berlin: De Gruyter.