Middle Ru: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1,724: | Line 1,724: | ||

<p>Being functionally identical to verbs, Middle Ru adjectives can take any affix that could apply to verbs. For instance, the causative prefix <em>ižy-</em> may be used to form the verb <em>ižyaxan-</em>, meaning 'to cause [something or somebody] to grow old, to age'.</p> | <p>Being functionally identical to verbs, Middle Ru adjectives can take any affix that could apply to verbs. For instance, the causative prefix <em>ižy-</em> may be used to form the verb <em>ižyaxan-</em>, meaning 'to cause [something or somebody] to grow old, to age'.</p> | ||

<p>Comparatives (and superlatives) are expressed through the prefix <em>ñir-</em> or <em>ñwr-</em>, meaning 'to surpass', which may also be applied to any other verb in order to express than an action has been conducted to a higher degree than some reference level. This prefix is not to be confused with a voice mark as it does <b>not</b> modify the valency of the verb. Thus, <em>ñiraxan</em> is not to be understood as transitive 'to be older than [someone]' but as a still-intransitive 'to be older', without making | <p>Comparatives (and superlatives) are expressed through the prefix <em>ñir-</em> or <em>ñwr-</em>, meaning 'to surpass', which may also be applied to any other verb in order to express than an action has been conducted to a higher degree than some reference level. This prefix is not to be confused with a voice mark as it does <b>not</b> modify the valency of the verb. Thus, <em>ñiraxan</em> is not to be understood as transitive 'to be older than [someone]' but as a still-intransitive 'to be older', without making explicit who the person or object is older than, which is left out to context. Examples include:</p> | ||

<p><em><b>Ñiraxanarlys mimýaħ.</b></em></p> | <p><em><b>Ñiraxanarlys mimýaħ.</b></em></p> | ||

| Line 1,730: | Line 1,730: | ||

<p><em><b>Axanarlys xek'aħ, ñiraxanarly mimýaħ.</b></em></p> | <p><em><b>Axanarlys xek'aħ, ñiraxanarly mimýaħ.</b></em></p> | ||

<p><em>The man was older | <p><em>The woman was old, the man was older ~ The man was older than the woman.</em></p> | ||

<p><em><b>Zeviħals mimýaħ añiraxána.</b></em></p> | <p><em><b>Zeviħals mimýaħ añiraxána.</b></em></p> | ||

| Line 1,903: | Line 1,903: | ||

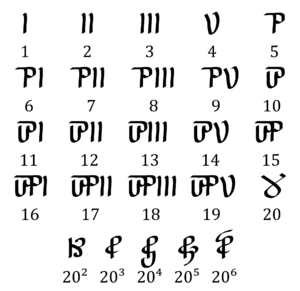

<p>The number 'one' is always expressed as <em>ýla</em>, although in combining forms it may also appear as <em>ylárra</em> (literally 'and one', although shifting the stress to the second syllable unlike the more general usage of the affix <em>-rra</em>). The form <em>ylárra</em> is most commonly found after 'round' numbers such as <em>jat</em> (twenty); in a sense <em>ylárra</em> indicates that the value is one more than a number that would be more likely to be expected. The forms <em>játel</em> and <em>c'étel</em> alternate with <em>jat</em> and <em>c'et</em> (respectively) when not followed by any further numerals.</p> | <p>The number 'one' is always expressed as <em>ýla</em>, although in combining forms it may also appear as <em>ylárra</em> (literally 'and one', although shifting the stress to the second syllable unlike the more general usage of the affix <em>-rra</em>). The form <em>ylárra</em> is most commonly found after 'round' numbers such as <em>jat</em> (twenty); in a sense <em>ylárra</em> indicates that the value is one more than a number that would be more likely to be expected. The forms <em>játel</em> and <em>c'étel</em> alternate with <em>jat</em> and <em>c'et</em> (respectively) when not followed by any further numerals.</p> | ||

<p>Unlike English, Middle Ru numerals | <p>Unlike English, Middle Ru numerals always follow the noun to which they apply: <em>emimy jat</em> for '20 men'.</p> | ||

<p>Ordinals are formed in a relatively unusual way. The first element is described as <em>ac'ála</em>, the participle of <em>c'al</em>, 'to come first'. Other ordinals are formed by using the particle <em>swr</em> and the number of elements that come <em>before</em>, followed by the suffix <em>-(a)rra / -(å)rrå</em>. Thus, 'the second man' becomes <em>mimy swr ýlarra</em> (~ man preceded by one other); 'the tenth mountain' becomes <em>ħóxol swr sótårrå</em> (~ mountain preceded by nine others) and so on.</p> | <p>Ordinals are formed in a relatively unusual way. The first element is described as <em>ac'ála</em>, the participle of <em>c'al</em>, 'to come first'. Other ordinals are formed by using the particle <em>swr</em> and the number of elements that come <em>before</em>, followed by the suffix <em>-(a)rra / -(å)rrå</em>. Thus, 'the second man' becomes <em>mimy swr ýlarra</em> (~ man preceded by one other); 'the tenth mountain' becomes <em>ħóxol swr sótårrå</em> (~ mountain preceded by nine others) and so on.</p> | ||

| Line 1,909: | Line 1,909: | ||

<h1>The Middle Ru script</h1> | <h1>The Middle Ru script</h1> | ||

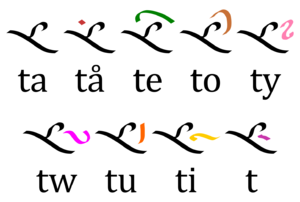

<p>The Middle Ru | <p>The Middle Ru script, the native writing system for the language, is an abugida where each consonant is represented by a letter while vowels other than /a/ are marked through diacritics above the consonant. Much as in the Brahmic scripts from India, a <em>virama</em> mark is used to supress the inherent /a/ in a consonant in order to mark codae. Thus, the word <em>xek'aħ</em> (absolutive singular form of <em>xek'a</em>, 'woman') would be written with the consonant letter for <em>X</em> plus the <em>E</em> diacritic, the consonant letter for <em>K'</em> (which, on its own is read as <em>k'a</em>), the consonant letter for <em>Ħ</em> with the <em>virama</em> diacritic to indicate that it is to be read as a word-final <em>-ħ</em> rather than as the sequence <em>ħa</em>. The abugida is supposed to be a descendant from the Ancient Hulamic script used for Proto Ru-Hulam.</p> | ||

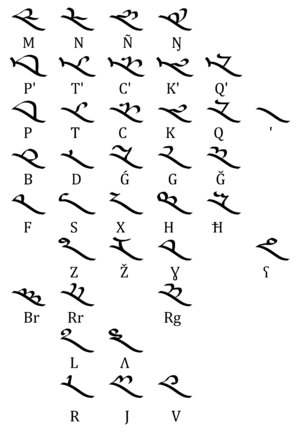

<p>The glyphs used for Middle Ru consonants have a characteristic shape based on a slightly curved slanted lined over which further strokes are drawn (except for the glottal stop, marked by the slanted line alone). The characters are partially featural. For instance, the glyphs ejectives are clearly derived from the corresponding plain plosives.</p> | <p>The glyphs used for Middle Ru consonants have a characteristic shape based on a slightly curved slanted lined over which further strokes are drawn (except for the glottal stop, marked by the slanted line alone). The characters are partially featural. For instance, the glyphs ejectives are clearly derived from the corresponding plain plosives.</p> | ||

Revision as of 00:47, 14 April 2020

Middle Ru is an a priori language that would have been spoken in the western regions of the fictional island of Rauna during its Middle Period (roughly corresponding to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance). Within its internal history, it belongs to the Ru-Hulam languages native to the Drysian continent, situated west of the Rauna region, half an ocean away.

The Middle Ru language was known natively as ħórwx lå Rgu /ˈχo.ɹʉʃ lɒ ʀu/, "language of the Ru"; the name Ru or Rgu /ʀu/ itself is thought to be related to the first person pronoun or rru /ru/, 'I, me'. Extrafictionally, this is a leftover from the development of Raunan conlangs when they were referred to by their word for the first person pronoun.

Internal history

Ru-Hulam period

The Middle Ru language can be traced back to Proto Ru-Hulam, a language that would have been spoken in the northeastern regions of Drysia, one of the three major continents in Rauna's planet. In ancient times, the the Ru-Hulam peoples (often referred to simply as 'Hulam') came to be united under a powerful monarchy known as the First Hulam Empire. This nation would came to rule over a sizeable fractionof the continent. In particular, the Hulam conquered and slaved their more populous neighbours to the east, the Qwiyen, and made the Mikken tribes in the north into a client state.

During the heyday of their empire, the Hulam also established ties with other nations, including the Fulao peoples who had formed a similarly prosperous league of city states in Miwep, a small continent south of Drysia. Rivalry between the expansionist Hulam and Fulao peoples led to at least three attempts of invasion, all unsuccessful thanks to the latter's then-unrivaled naval expertise.

Unable to overcome the Fulao's prowess at seafaring, the Hulam empire eventually sought to imitate it. As news about the Fulao discovery and settlement of the Shawi islands in the great eastern ocean reached the Hulam courts, the emperor came to be determined to launch an ambitious effort to reach new lands further east and colonize them. Although the results were disastrous for the most part (with several expeditions wrecking in the high seas and the imperial finances taking a toll for what many viewed as a weak emperor's vanity project), one expedition managed to reach Rauna, a vast island once dominated by a powerful empire which had recently succumbed. These circumstances allowed the Hulam to establish a colony of their own in western Rauna. However, soon thereafter the already weakened Hulam Empire, itself would meet a similar fate, taking a major blow from the Great Qwiyen Revolution, which not only liberated their people from an oppressive rule but would also establish a Qwiyen state that would came to rule the Hulam peoples themselves during much of the following centuries.

As the Hulam empire fell in the Drysian continent, the colonists in Rauna lost all (if not all) contact with their ancestral homeland. Instead, they came to develop a distinct ethnic identity as the Ru. A sizeable number of Qwiyen slaves they had brought alongside them would develop into the Xhuei peoples of southern Rauna.

Although the starting population of each group is still a matter of debate among Raunan historians, it is often considered to have been in the thousands for both groups. Early Ru and Xhuei people, however, were known to have intermarried with the native peoples. Genetic studies confirm that modern Ru and Xhuei peoples are more closely related to other Raunan populations than to their Drysian ancestors, although Y-chromosome haplogroups most commonly found in north-eastern Drysia can still be identified.

The Ru in Rauna

The Ru were one of the first ethnic groups that arrived to the Raunan region after the Ancient Period which is why they are said to be one of the Younger Raunan peoples; contrasting with the Older Raunan ethnicities that had inhabited the island prior to their arrival. Ru peoples mostly occupied territories in western Rauna. They quickly took over many of the western provinces of the ruinous Raunic empire. The Ru also conquered territories that formerly belonged to the Iyau peoples, giving rise to a long-lasting bitter rivalry between the two nations.

During much of the Middle Period the Ru played a major role in the island as the city of Cadarmen became the main trade hub on the island due to its strategic location next to a passage through the Myqyraghar mountain range that divides the Raunan mainland. Control over this strategic point allowed the wealthy lords of Cadarmen to establish an extensive Ru Kingdom which quickly became a major power in the Rauna region.

By the end of the Middle Period, maritime trade (mostly conducted by the Amatl nations in northern Rauna) gained prominence, while the land-based trade routes controlled by the Ru kingdom saw a sharp decline. This would eventually led to an economic and political crisis in the kingdom, with a major rebellion in the mountainous eastern frontier lands. Situations worsened when the Iyau launched a successful military offensive on the western lands of the Ru Kingdom, secretly aided by the Amatl league who sought to weaken their economic rivals.

By the Modern Period, the Middle Ru language had diverged into three varieties: Eastern Ru, Western Ru and the Iyau-Ru language (spoken in territories reconquered by the Iyau, also referred to as 'Lower Iyau').

External history

Extrafictionally, Middle Ru was the first Raunan language to be created, back in July 2018. The concept behind the Raunan languages project was to create a series of unrelated languages out of which mixed languages would develop at a later time.

It was decided from the start that Middle Ru would be a typologically unusual and rather harsh-sounding language in order to have it contrast with its neighbours.

Although the concept that the Ru peoples would have arrived to Rauna after its classical period was decided early on, work on the Proto-Ru-Hulam language and Ru history prior to their arrival to the Raunan region only began in 2020. The post-facto development of an ancestor language led to a series of retcons as well as a overhaul of Middle Ru's polypersonal marking.

Phonology

Middle Ru features a rather complex phonology distinguishing 8 vowels and 37 consonants, including multiple trills, uvulars and the pharyngeal fricative /ʕ/. This led speakers of other Middle Raunan languages to describe Ru as 'harsh sounding' or 'guttural'.

Consonants

The following table shows Ru's consonant inventory (uppercase and lowercase romanization on the left, IPA phonemic transcriptions on the right):

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Laryngeal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | M m /m/ | N n /n/ | Ñ ñ /ɲ/ | Ŋ ŋ /ŋ/~/ɴ/ | |||

| Plosive | Ejective | P' p' /pʼ/ | T' t' /tʼ/ | C' c' /cʼ/ | K' k' /kʼ/ |

Q' q' /qʼ/ | ( ' ) /ʔ/ |

| Unvoiced | P p /p/ | T t /t/ | C c /c/ | K k /k/ | Q q /q/ | ||

| Voiced | B b /b/ | D d /d/ | Ǵ ǵ /ɟ/ | G g /g/ | Ğ ğ /ɢ/ | ||

| Fricative | Unvoiced | F f /f/ | S s /s/ | X x /ʃ/ | H h /x/ | Ħ ħ /χ/ | |

| Voiced | Z z /z/~/dz/ | Ž ž /ʒ/ | Ɣ ɣ /ɣ/ | ʕ ʕ /ʕ/ | |||

| Approximant | R r /ɹ/ | J j /j/ | V v /w/ | ||||

| Trill | Br br /ʙ/ | Rr rr /r/ | Rg rg /ʀ/ | ||||

| Lateral | L l /l/ | Λ ʎ /ʎ/ | |||||

Notes:

- Glottal stops are only written (as an apostrophe) in word-final position. As the language does not allow onset-less syllables, vowels not preceded by a consonant in writing can be assumed to have an unwritten glottal stop as their onset.

- Middle Ru had an orthography of its own. The Latin script romanization is extrafictional.

- The nasal <ŋ> is typically velar, but may be pronounced as an uvular [ɴ] word-finally or when next to another uvular consonant. In the romanization, the uppercase glyph that resembles a capital N with a hook (as used for capital ŋ in some Saami languages) is preferred to the alternative that looks like an upscaled lowercase <ŋ> (as typically found in African orthographies, see the Wikipedia article on the letter Eng for more information).

- In the romanization, the uppercase form of <ħ> (for /χ/) should properly have the additional bar through the vertical stroke on the left, rather than having the bar cross both vertical strokes as in the Unicode character <Ħ> (used instead due to the lack of support for the proper variant of the glyph).

- The voiced phoneme romanized as <z> varied freely between being a true fricative /z/ or an affricate /dz/. The latter realization seems to have prevailed in Cadarmen, the capital of the Ru kingdom.

- The ejective plosive /pʼ/ seems to have merged into /p/ except in eastern dialects.

- The lateral /l/ may be palatalized to /ʎ/ in some contexts, but this is not reflected in native Middle Ru writing nor in the romanizations.

- The sequence /ɹ.g/ is romanized as <r·g>, as <rg> stands for /ʀ/.

Vowels and vowel harmony

The vocalic inventory of the language consists of eight vowels evenly divided into two harmony classes ('clear' front vowels and 'dark' back vowels).

| Clear |

Dark |

|---|---|

| I i /i/ | U u /u/ |

| Y y /y/ | W w /ʉ/ |

| E e /ø/ | O o /o/ |

| A a /a/ | Å å /ɒ/ |

It should be noted that the vowel transcribed as <e> is actually a rounded /ø/. The vowel /a/ is front vowel [a] rather than central [ä].

All vowels may be reduced to a schwa (/ə/) when they occur far from the primary stress of a word. Typically, this happens for vowels 2 syllables (or more) away from the main stressed syllable of a polysyllabic word. Monosyllabic particles may also have their vowels reduced to a schwa, at least in less formal registers. This kind of vowel reduction is not reflected in writing.

Affixes must agree with the vowel harmony class of the stems they attach to. While a few affixes have distinct and potentially unrelated 'clear' and 'dark' variants, most affixes look follow a certain set of vowel alternations known as 'vowel classes'. Each vowel class (represented as the umlauted vowels <ä ï ö ü ÿ> for the purposes of this dictionary and grammar only) changes to a clear or a dark realization matching the harmony class of the primary stems they are applied to as shown in the following table:

| Vowel class | Clear realization | Dark realization |

|---|---|---|

| ä | A a /a/ | Å å /ɒ/ |

| ï | I i /i/ | W w /ʉ/ |

| ö | E e /ø/ | O o /o/ |

| ü | Y y /y/ | W w /ʉ/ |

| ÿ |

I i /i/ | U u /u/ |

For instance, the interrogative prefix is xö- changes to xe- before a clear-harmony stem and as xo- before a dark-harmony stem.

It should be noted that certain vowels correspond to more than one vowel classes: /i/ is the clear-vowel realization of both ï and ü while /ʉ/ is the dark-vowel realization of both ï and ÿ. Because of this, knowing one form of an affix dos not necessarily suffice to know the opposite form.

Phonotactics

Middle Ru allows a CV(G)(C) syllabic structure, where C stands for a consonant, V for a vowel and G for any of the three phonemes considered as 'glides': /ɹ j w/. The following restrictions apply:

- All syllables require an onset consonant; borrowings that would otherwise begin with a vowel are fitted into Middle Ru phonotactics by adding an initial /ʔ/.

- The approximants/glides /ɹ j w/ may only occur immediately after a vowel. Thus, they occur word-initially nor following a closed syllable.

- Only /ɹ j w/ are allowed as word-medial codae.

- The following consonants might appear in a word-final coda: unvoiced stops, nasals, any fricative (including /z/~/dz/), approximants and trills. Codal stops, nasals and fricatives may be preceded by a glide (/ɹ j w/).

- Two identical consonants cannot form a cluster. Thus the sequences /ɹ.ɹ/, /j.j/ and /w.w/ are not allowed.

Prosodic stress is lexical and non-predictable. Oxytone words (those stressed on the last syllable) are always unmarked for stress. Otherwise, stress may be indicated with an optional diacritic in Middle Ru's native script and with an acute accent in the romanization (<á ǻ é í ó ú ý ẃ>). Vowels more than two syllables away from the stressed syllable in a word are reduced to a schwa.

The stressed syllable of a noun does not vary in its inflection. For example, the word mimy (man) will always be stressed in the y, even when suffixes are added as in the absolutive form mimýaħ. The written accent in forms such as mimýaħ might be absent by mistake in some inflection tables.

Verbs, on the other hand, have a variable stress syllable wholy depending on their suffixes.

Phonological history

Middle Ru is supposed to descend from a language known as Proto Ru-Hulam (PRH) which would have been spoken by the ancestors of the Ru people prior to their arrival to Rauna. Extrafictionally, however, Proto Ru-Hulam was actually back-derived from Middle Ru.

A significant share of Middle Ru's vocabulary can be traced back to Proto Ru-Hulam terms. Although in some cases the resemblance is still clearly identifiable, in others the relationship is obfuscated due to sound changes and semantic shifts. This section aims to present the most usual correspondences between Proto Ru-Hulam and Middle Ru, although it should be noted that several exceptions might be found.

One major difference between Proto Ru-Hulam and its Ru descendants in Rauna can be found in its consonantal inventory where most phonemes occur in contrasting pairs of one labialized and one non-labialized consonant such as /nʷ/ vs /n/. It is possible that the non-labialized consonants might have been palatalized to some extent (resulting in a /nʷ/ vs /nʲ/ contrast). This contrast was lost in Middle Ru, although it affected vowel development, with most PRH vowels splitting into rounded and unrounded variants. Thus, where the proto-language might contrast the syllables /ni/ and /nʷi/ by their consonants (non-labialized /n/ and labialized /nʷ/), Middle Ru may inherit such syllables as /ni/ and /nʉ/, with contrasting vowel qualities instead. Middle Ru's vowel harmony is also a later development which may play a role in vowel correspondences. For instance while PRH /nʷi/ would ordinarily yield /nʉ/ in Middle Ru, through vowel harmony the latter might be assimilated to /ny/ in a word dominated by a front vowel (in the 'clear' harmony class).

Vowels

For the most part, vowel correspondences are as follows:

| Proto Ru-Hulam |

Middle Ru |

Example (Proto-RH to Middle Ru) |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a /a/ | a /a/ | ʔaʔxa land |

áɣa /ˈa.ɣa/ land |

If not labialized. May harmonize to å /ɒ/. |

| å /ɒ/ | dʷaf to eat |

dåf /dɒ.f/ to eat |

Next to labialized consonants. May harmonize to a /a/. |

|

| i /i/ | i /i/ |

mimú man |

mimy /miˈmy/ man |

If not labialized. May harmonize to u /u/. |

| w /ʉ/ | drʷis western lands |

rrws /rʉs/ west |

Next to labialized consonants. May harmonize to y /y/. |

|

| o /o/ [o]~[ɤ] (?) |

e /ø/ | xoʔká wife |

xek'a /ʃøˈkʼa/ woman |

If not labialized. May harmonize to e /ø/. |

| o /o/ | hʷorʷ to speak |

ħor /χo.ɹ/ to speak |

If labialized. May harmonize to o /o/. |

|

| u /ɯ~u/ | y /y/ | gusʷ you, 2s |

ǵy /ɟy/ you, 2s |

If not labialized. May harmonize to w /ʉ/. |

| u /u/ | hʷur to defend |

ħur /χu.ɹ/ to own |

If labialized. May harmonize to i /i/. |

|

| ə /ə~ʌ/ | o /o/ | bʷəʔt obstacle, hardship |

bot' /botʼ/ river |

If labialized. May harmonize to e /ø/. |

| a /a/ | drəʔ to unite |

-rra /ra/ and |

If not labialized and next to an uvular or glottal. May harmonize to å /ɒ/. |

|

| w /ʉ/ | kəñ to build |

cwñ /cʉ.ɲ/ to build |

Elsewhere. May harmonize to y /y/. |

|

A number of irregular developments are observed, however. For instance the Proto Ru-Hulam word xʷən (tu rule) would have been expected to yield *hon but instead yields Middle Ru hwn (also meaning 'to rule').

Consonants

As mentioned before, most Proto Ru-Hulam consonants came in two variants: labialized and non-labialized. This distinction mostly collapsed in Middle Ru other than leaving a mark in vowel qualities. Nontheless, certain consonant pairs evolved differently depending on whether they used to be labialized or not.

Aside from laryngeal /ʔ/ and /ʕ/ (the latter of which seems to have developed out of an earlier uvular [ʁ]), Middle Ru distinguishes five places of articulation: labial, alveolar, palatal, velar and uvular. The latter three series actually arose from two dorsal series (velar vs uvular; Proto Ru-Hulam lacked true palatal consonants), which depending on labialization as shown in the following table.

| Proto Ru-Hulam places of articulation + labialization |

Middle Ru places of articulation |

Examples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | Plosives |

Fricatives | |||||||

| Unvoiced | Voiced | ||||||||

| PRH | MR | PRH | MR | PRH | MR | PRH | MR | ||

| Labial, not rounded | Labial |

mimú man |

mimy man |

pəʔñə stone |

p'áñe stone |

bilʒ fifteen |

biz squad |

fahʷ to sleep |

farğ to sleep |

| Labial, rounded | mʷaʔ 3s |

ma' 3s |

pʷiʔɬ breast milk |

p'wl milk |

bʷəʔt obstacle |

bot' river |

- | ||

| Coronal, not labialiazed | Alveolar | nosʷ thrist |

nes thirst |

tuɬ husband |

tyl lord |

dañ to grow |

dañ to stick out |

samʷ hand |

sam arm |

| Coronal, labialized | nʷumʷ knee |

num knee |

tʷəʔt edge |

t'ot' corner |

dʷaf to eat |

dåf to eat |

sʷuyəm seed |

sújåm seed |

|

| Velar, not labialized | Palatal | ñus ten |

ñy ten |

kəñ to build |

cwñ to build |

gawəm neck |

ǵav neck |

xoʔká woman |

xek'a woman |

| Velar, labialized | Velar | ñʷo moon |

ŋo moon |

kʷoʔr jewellery |

k'or gem |

gusʷ you |

gy you |

xʷitʷ to leave |

hwt to leave |

| Uvular, not labialized | - | qoʔt house |

k'et house |

- | howəm commander |

hev king |

|||

| Uvular, labialized | Uvular |

- | qʷur fist, punch |

qurt hand |

- | hʷorʷ to speak |

ħor to speak |

||

As usual, a number of irregular developments can be found. Instances where non-labialized uvulars are inherited as uvular consonants (rather than as velars as show in the table) are particularly common. It has been proposed that this might be explained by the presence of two early Ru-Hulam dialects among the first colonists in Rauna although this theory has fallen short of consensus among Raunan linguists.

It should be noted that Proto Ru-Hulam didn't seem to contrast labialization (or rounding) for its labial fricative f and had neither uvular nasals nor voiced uvular plosives. Middle Ru's voiced uvular plosive ğ /ɢ/ mostly originated due to irregular developments and borrowing, although it remains one of the least used phonemes in the language.

The Proto Ru-Hulam language lacked ejectives. These developed due to the influence of glottal stops which PRH syllabic structure allowed between a vowel and further consonants (even in coda position). The resulting CVʔC(V) structure would be simplified to CVC(V) in Middle Ru, which did no longer accept non-word-final glottal stop codae, but the glottalic element would cause neighbouring voiceless plosives to turn into ejectives as in pʷiʔɬ where the preceding stop /pʷ/ becomes an ejective p'wl or bʷəʔt where the following /t/ is turned into an ejective instead: bot'. Words were both the preceding and the following consonant were voiceless plosives such as qoʔt or tʷəʔt may either develop an ejective in the first stop (as in k'et) or in both stops (as in t'ot'). Although there seems to be no clear rule governing these developments, it can be noted that roots where both consonants are identical such as tʷəʔt~t'ot' are markedly more prone to have both plosives evolve into ejectives.

Voiced fricatives (aside from /ɮ/, which shall be discussed later) are also an innovation in Middle Ru. They may arise sporadically from their voiceless counterparts (uvular /χ/ in the case of pharyngeal /ʕ/) in the vecinity of other voiced consonants (as in PRH bʷuh, 'to stir', to MR buʕ, 'to mix') or in the same contexts that cause plosives to become ejective (PRH xʷoʕn, 'town', to MR ɣen, both meaning 'town'; PRH ʔaʔxa to MR áɣa, both meaning 'land'). Any instances which could result in a voiced /f/ yield an approximant v /w/ instead: PRH muʕf 'to breathe', MR myv, 'to live'. Evidence indicates that in early Middle Ru (and possibly later in some dialectal pronunciations) these instances of Middle Ru v might have been realized as [v], contrasting with the phoneme /w/ as inherited from other sources (such as Proto Ru-Hulam /w/). The two sounds, however, had been fully merged in the Cadarmeni standard.

Unlike Middle Ru, Proto Ru-Hulam featured two lateral fricatives: voiceless /ɬ/ and voiced /ɮ/ (the latter often transcribed as a non-ligated lʒ for the sake of convenience) in addition to the lateral approximant /l/. Voiceless ɬ commonly merged into /l/, especially in coda-position, but could also yield palatal /ʎ/ near front vowels. For instance, the verb 'to give', ʎu (with an earlier variant ʎi), comes from PRH ɬi.On the other hand, the voiced lateral fricative lʒ would most commonly evolve into z /z/ (PRH kaʔlʒ, 'to slide', to MR c'az, 'to move forward') or ž /ʒ/ if in the vecinity of a front vowel: PRH ʔilʒ, 'to summon', yields the causative prefix ižy- (harmonized to užw- in dark-harmony words). Proto Ru-Hulam laterals did not contrast labialization, atlhough vowels in the vecinity of PRH /l/ will often evolve as if next to a labialized consonant: PRH lam yields MR låm (both meaning silver, with a back rounded å).

Middle Ru's three non-lateral approximants r /ɹ/, j /j/ and v /w/ correspond to Proto Ru-Hulam's approximants r (and rʷ; probably flaps /ɾ/ and /ɾʷ/), y /j/ and w /w/, except for instance of Middle Ru v which evolved as a voiced counterpart to f. Proto Ru-Hulam rhotic approximants contrasted labialization while y and w did not.

Proto Ru-Hulam also allowed syllable-initial clusters composed of a voiced plosive and a rhotic r or rʷ matching its labialization (or lack thereof). These sequences invariably became trills in Middle Ru, with br and brʷ yielding the rare bilabial trill br /ʙ/, dr and drʷ evolving into an alveolar trill rr /r/ and the clusters gr and grʷ becoming an uvular trill rg /ʀ/.

Grammar

Middle Ru is a polysynthetic language. It features a split ergative alignment. Its primary word order is VOS, with other arguments coming later. Middle Ru grammar tends to be head-initial .

Nouns

Middle Ru nouns may inflect for case, noun class and number. Declension paradigms also depend on the vowel-harmony class of each noun.

Nominal classes

The language distinguishes four noun classes. These are similar to genders in European languages, although they are mostly based on animacy. With few exceptions, the nominal class of a noun can normally be deduced from its meaning.

Class I nouns are used for people, deities, groups of people, kinship terms and living things that may not be eaten due to cultural reasons (including dogs, mollusks and arachnids but not most other animals).

Class II nouns might be classified as 'resources'. This includes most animals, edible plants (more on plant classification later), drinking water, fire, the sun, clouds, materials that might be used as fuel (such as firewood), wool and hides. Non-human body parts such as gills and wings also tend to belong to the second class.

Class III nouns mostly correspond to soft or flexible materials. This includes liquids other than drinking water, powders, gasses, (including air), most prepared foods, abstract nouns related to words, speech, memory and thoughts and body parts that are either soft (such as the skin, ears) or that may be moved independently (including hands, arms, lips, eyes).

Class IV nouns mostly include hard materials, most man-made objects (especially buildings, tools and machines) and hard body parts that cannot move independently such as teeth, bones and nails. Shells and eggs are also classified as belonging to class IV.

Plants and fungi belong to the fourth class with the following exceptions:

- Long grasses, vines and similar plants belong to the third class.

- Flowers belong to the third class unless they are edible by humans. In the latter case, they are classified as class II instead.

- Fruits, grains, nuts and mushrooms only belong to class IV if they have a hard surface that requires grinding or a similar process for human consumption. Otherwise, they will be class II if edible or class III otherwise.

- Seeds belong to the second class if edible and to the fourth class otherwise.

- Woods are treated as class II nouns when intended to be used as fuel or as class IV otherwise. The same noun might take affixes for different classes depending on its intended purpose.

Middle Ru grammar often treats class I nouns ('animate') differently than nouns from other nominal classes ('inanimate'). For instance, the base form of a class I noun corresponds to the ergative case while the base form of inanimate nouns corresponds to the absolutive case instead.

Number

Number marking is optional in Middle Ru; speakers may drop number affixes whenever it is clear from context. This particularly often the case for inanimate nouns (classes II, III and IV).

Animate (class I) nouns are considered to be singular by default. The prefix ö- (this is, e- for clear vowel-harmony class and o- for dark vowel-harmony) is used to form plurals.

For other nouns, a singular/singulative suffix -l is used to explicitly mark a noun as singular. Plural marking with the prefix ö- may also be found in inanimate nouns, although this seems to be have been limited to situations when a singular meaning would otherwise be expected from the context.

The singulative suffix -l may metathesize when applied to a stem with a final stop such as sek (tree, trees), resulting in selk (a tree). Otherwise, consonant-ending stems will take the suffix with an epenthetic -ö- (as in darmárem to darmáremel).

Singulatives are also used to derive nouns for individuals out of intrinsically collective nouns. This is also found in class I nouns (for instance deriving qanal 'family member, relative' from qana, 'family'). The newly derived singulative noun may then take further number affixes such as eqanal for 'family members'.

| Harmony class | Base form | Plural | Singulative | Singulative+Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animate noun (class I) |

Clear | xek'a | exek'a | N/A | N/A |

| woman | women | ||||

| Dark | ħúrwm | oħúrwm | N/A | N/A | |

| soldier | soldiers | ||||

| Inanimate noun (classes II, III, IV) |

Clear | c'áza | ec'áza | c'ázal | N/A |

| valley, valleys |

valleys (rare) |

a valley | |||

| Dark | ħox | oħox | ħóxol | N/A | |

| mountain, mountains |

mountains (rare) |

a mountain | |||

| Collective animate (class I) noun (clear harmony example) |

qana | eqana | qanal | eqanal | |

| family | families | relative | relatives | ||

| Collective inanimate (class IV) noun (clear harmony example) |

p'áñe | N/A | p'áñel | ep'áñel | |

| stones, stone as a material |

a stone |

several stones (very rare) |

|||

| Noun with infixed singulative -l- (clear harmony example) |

sek | esek | selk (not *sékel) |

N/A | |

| tree, trees |

trees (rare) | a tree | |||

Collective nouns (independently of their class) are typically treated as being singular for the purposes of verb agreement.

Case

Middle Ru nouns are inflected for case. This is done through suffixes for cases related to morphosyntactic alignment (i.e. with whether a noun is the subject, direct object or indirect object of a verb) and through prefixes for other cases such as the possessive and the locative.

| Case | Usage |

Affixes |

Example | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base form (or nominative) |

Used when referring to a lexeme. Listing in dictionaries. As a vocative. Second element of a copula. |

No affix | Mazávaħ mimy. | Mazáva is a man. |

| Absolutive | Subjects of intransitive verbs. Objects of transitive verbs. Indirect objects of ditransitive verbs. First element of a copula. |

-aħ, -oq (animate nouns) |

Myfarğaryls mimýaħ. | The man is sleeping. |

| No affix (Inanimate nouns) |

Zeviħárga ħox. | I have seen the mountain. | ||

| Ergative | Subjects of transitive verbs. Subjects of ditransitive verbs. |

No affix (animate nouns) |

Zevarñi ħox mimy. | The man sees the mountain. |

| -at, -ås (class II) -ix, -wx (class III) -yh, -uh (class IV) |

Bruswlws mimýaħ ħóxuh. | The mountain crushed the man. | ||

| Secundative | Direct object of ditransitive verbs. Objects of type-I applicatives. |

-t, -et, -wt | Λuwrrå mimýaħ ħóxwt. | I gave the mountain to the man. |

| Possessive (I) | Most kinds of possession. |

la-, lå- | ħox lamimy | the mountain of the man |

| Possessive (II) | Specific kinds of inalienable possession. |

ha-, hå- | qúrtol hamimy | the man's hand |

| Locative | Location: in, at. |

by-, bw- | bwħox | at the mountain |

| Instrumental | With, using as a tool. Causative agents. |

syr-, swr- | swrqurt | with the hands |

| Ornative | Having, with. | t'e-, t'o- | xek'a t'emimy | a woman with a man/husband |

| Privative | Lacking, without. | myr-, mwr- | xek'a myrmimy | a woman without a man/husband |

Case-marking prefixes are often romanized a separate word when preceding a proper noun: as in lå Rgu (of the Ru) instead of *låRgu. This difference is not obseverd in native Ru writing

Nominative (base form)

In a few some contexts, Middle Ru uses the base form of a noun (lacing any case affixes; other affixes such as number marking might be used in these contexts). This base form (which may be dubbed a 'nominative') coincides with the ergative form for animate nouns (class I) and with the absolutive case for inanimate nouns (classes II, III and IV).

A relatively unusual feature of Middle Ru is that copulas such as 'X is Y' require the first noun X to be in the absolutive case (marked for animate nouns) but use the base form of the second noun Y. Thus 'the man is a soldier' would translate as mimýaħ ħúrwm (using zero copula, as usual for present tense) but 'the soldier is a man' would be ħúrwmoq mimy; where mimýaħ and ħúrwmoq are the absolutive forms of mimy (man) and ħúrwm (soldier).

Ergative and absolutive

Middle Ru mostly follows an ergative-absolutive alignment, meaning that one case (the ergative) is used for the subjects of transitive verbs (those who also have a an object) while a different case (the absolutive) is used for objects of transitive verbs and for the sole argument of intransitive verbs. This means that in the sentences 'the woman sees the bird' (transitive) and 'the man sleeps' (intransitive), the noun 'woman' would take the ergative case while 'bird' and 'man' would take the absolutive case. Intransitive verbs, rather than being thought of as verbs with a subject but no object, may be thought of in Middle Ru as having an absolutive object but no ergative subject instead.

The way these two cases are expressed depends on the nominal class of the noun. Class I nouns are unique in taking a suffix for the absolutive case while no suffixes are added for the ergative. On the other hand, other noun classes (II, III and IV) have and unmarked absolutive case and take different suffixes (depending on their nominal and vowel-harmony classes) for the ergative. This reflects the fact that animate class I nouns are more likely to appear as subjects in transitive sentences and thus remain unmarked in agent roles.

| Absolutive | Ergative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Clear harmony | -aħ | Unmarked |

| Dark harmony | -oq | ||

| Class II | Clear harmony | Unmarked | -at |

| Dark harmony | -ås | ||

| Class III | Clear harmony | Unmarked | -ix |

| Dark harmony | -wx | ||

| Class IV | Clear harmony | Unmarked | -yh |

| Dark harmony | -uh | ||

Secundative

Ditransitive verbs (those that, in addition to a subject, have both a direct object and an indirect object) feature a secundative alignment in Middle Ru, meaning that direct objects receive a separate 'secundative' case while indirect objects are marked with the same case as the only object of a monotransitive verb (in this case, with the absolutive case). This is the opposite of what occurs in most European languages where it is the indirect object that is marked with a third case (the dative).

The archetypical example of a ditransitive verb is the verb 'to give' (Middle Ru ʎu), which has a subject (the one that gives something to someone else) that is to be marked with the ergative case, a direct object (the thing given to someone else) that is to be marked with the secundative case and an indirect object (the person that is given the thing) which is marked with the absolutive case.

The secundative case is expressed with a suffix: -t for nouns whose base form ends in a vowel or /l/ (including singulatives), -et for other clear-harmony nouns and -wt for other dark-harmony nouns.

There are other verbs with three arguments, however, which may take different cases. For instance, in causative constructions (X makes Y do something [to Z]), the person X that causes the action to occur (Y does something [to Z]) will be expressed in the instrumental case instead. All four arguments are found in the following example:

Užwʎuwħåls swrħúrwm xek'a mimýaħ p'áñelt.

CAUS-give-PRF-3.ANIM>3.SG.PST INS-soldier woman man-ABS stone-SGV-SEC

The soldier (INS) had the woman (ERG) give the stone (SDT) to the man (ABS).

Possessives

Posession is expressed by having a possessive form of a noun follow the possessed noun: p'áñel lamimy for "the man's stone", literally "stone (p'áñel) of the man (lamimy, possessive form of mimy, 'man')".

Middle Ru possessives are generally formed with the prefixes la- and lå-. In some specific contexts, however, a different set of prefixes is used: ha- and hå-. The second set of prefixes are restricted to indicate the posession of body parts and certain relatives: parents, grandparents and other direct ancestors, sons and direct male-line descendants, siblings, uncles on the male line (ie brothers of one's father) and their sons (but not other kinds of cousins). Daughters and descendants other than in a direct-male line may uncommonly be described with a second-type posessive while, conversely, sisters and male-line cousins may be found with first-type possessives albeit rarely. This reflects the traditional Ru views of what relatives were considered to be an inalienable part of one's household, as the patriarchal patrilocal Ru society considered that daughters left their father's household upon marrying, joining her husband's instead. It should be noted, however, that ha-/hå- prefixes seem to have been restricted to blood-relatives; even though a married woman would be considered to have joined her husband's household, only her biological parents would be referred to as being haxek'a (possessive II), while her parents-in-law would always be described as laxek'a (possessive I).

Some words such as qana (family) may be described with either possessive: 'the woman's family' could be qana laxek'a or qana haxek'a, with no semantic difference between the two.

Locative

On its own, the locative case (expressed with the prefixes by- or bw-) is restricted to static location in or at a place. Other kinds of locative phrases will use an auxiliary word before the basic locative form of the noun. These preposition-like auxiliary nouns are often locative-case nouns themselves. For instance, 'below' uses the preposition bycym, the locative form of cym 'feet'; 'below the tree' becomes bycym byselk, literally 'at the foot of the tree'.

Locatives that apply to a complete sentence may be found either right after the verb or at the very end of the sentence. Locatives that describe the location of a noun follow the noun phrase they modify. This means that Myfarğaryls mimýaħ bycym byselk may translate either as "the man is sleeping below the tree" or as "the man below the tree is sleeping". The alternative form Myfarğaryls bycym byselk mimýaħ would unambiguously translate as 'the man is sleeping below the tree'.

Other cases

There are multiple constructions in Middle Ru that correspond to the English preposition 'with'.

The instrumental case (prefixes syr- and swr-) is used for indicating a tool employed to carry an action. This includes languages: ħorårwk swrħorwx lå Rgu for 'I speak in/using the (Middle) Ru language'. It should be noted, however, than tools may also be incorporated into a verb. The instrumental case is also used to indicate causative agents, as mentioned in the previous section about the dative case.

The ornative case (prefixes t'e- and t'o-) is used to indicate that the modified noun owns or is otherwise in possession or equipped with a thing. It could be "that has". For instance ɣen t'obot' translates as "a town (ɣen) with a river (bot')", a town that has access to a major river. Conversely, the privative case (prefixes myr- and mwr- is used to indicate a lack, 'without': ɣen mwrbot' 'a town without [acces to a major] river',

In order to express that someone is accompanied by someone or something (rather than being in posession of the object as in the ornative case), the comitative clitic =rrä is used, which covers both the usage of English 'with' and 'and'. Thus, while xek'a t'emimy (woman ORN-man) translates as 'a woman with a man ~ that has a husband', the phrase xek'a mimýrra may be translated both as 'a woman accompanied by a man' or as 'a woman and a man'. The lack of distinction between the comitative usage of 'with' and the conjunction 'and' between nouns is rather common cross-linguistically. The clitic =rrä (-(a)rra or -(å)rrå depending on vowel harmony) may follow either noun and it is always suffixed to the last element of its noun phrase. Thus "the man in the river and the woman in the city" translates as either mimy bwbót'årrå xek'a byɣen or as mymy bwbot' xek'a byɣénarra. Using the clitic on both elements of a conjunction may be done for emphasis: mimy bwbót'årrå xek'a byɣénarra for 'both the man in the river and the woman in the city'. Since the =rrä clitic is not a case marker, it may be used in conjunction with case affixes: for instance in myfarğarmis emimýaħarra exek'áħarra, 'both the men and the women are sleeping', we see the clitic combined with the class I absolutive case endings.

Roles not covered by the aforementioned cases are typically handled through prepostions.

Pronouns

| Base form |

Transitive subject |

Intransitive subject |

Transitive object |

Secundative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1s, I | rru | rroq | rrwt | |||

| 2s, you | ǵy | ǵwc | ǵyt | |||

| 3s | Class I | ma' | maaħ | majet | ||

| Class II | ña | ñat | ña | ñajet | ||

| Class III | nyajx | |||||

| Class IV | nyajh | |||||

| 1p | Exclusive we | orrus | orrusoq | orruswt | ||

| Inclusive we | ǵyrgy | ǵyrgyc | ǵyrget | |||

| 2p, plural you | jeǵy | jeǵyc | jeǵyt |

|||

| 3p | Class I | ymy | ymyjaħ | ymyjet | ||

| Other | iñy | iñat | iñy | iñet | ||

Middle Ru pronouns differ from regular nouns in a number of ways. Most prominently, first and second person pronouns have an nominative-accusative alignment rather than the ergative-absolutive found elsewhere in the language. This means that first and second person pronouns that occur as the subject of an intransitive verb will have the same nominative form as subjects of transitive verbs while their objects get a different accusative form. This contrasts with the behaviour found in third person pronouns and regular nouns where intransitive arguments are found in the same absolutive as transitive objects, while it is transitive subjects that get a separate ergative case.

First person plural pronouns ('we') also contrast clusivity. The exclusive pronoun orrus excludes the listener, being equivalent to "me and others, but not you". Meanwhile, the inclusive pronoun ǵyrgy indicates that the second person is also included, "you and me (and others)".

Singular third person pronouns must agree with the nominal class of their referent. Thus singular animate nouns will be referred to with the class-I pronoun ma' (he, she, singular they) while inanimate nouns will use ña (~ it) instead, with different ergative forms depending on their class (ñat for class-II, nyajx for class-III and nyajh for class-IV). Plural third person pronouns only observe an animacy distinction: class-I animates have ymy while inanimates have iñy, which declines in the same way for classes II, III and IV.

Possessives, locatives, instrumentals and other cases are formed regularly by applying the usual affixes to the base form of each pronoun. Thus we have lårru as an alineable possessive form of 'my', haǵy for inalienable 'your', byña for 'in it', t'eǵyrgy for 'including us' and so on.

It should be noted that Middle Ru is a pro-drop language. Since verbs are marked for their subjects and objects, pronouns are commonly dropped in those positions.

Verbs

As a polysynthetic language, Middle Ru features a rather complicated verb conjugation. Fortunately, the system is notoriously regular aside from a few exceptions.

A Middle Ru verb takes a series of affixes (both prefixes and suffixes) in order to indicate several grammatical categories such as voice, aspect, tense as well as person and number agreement both for subjects and objects. All these elements do always appear in the following fixed order:

- Interrogative prefix

- Voice prefix

- Verb stem (most basic form of the verb)

- Incorporated nouns (mostly tools)

- Aspect

- Tense, person and number (these categories are fused into a single suffix)

- Negative suffix

This structure is true for indicative verbs. Other moods will be explained later on.

Polar questions

The interrogative prefix xe- / xo- is used to transform a sentence into a polar question (one that may be answered as 'yes' or 'no'). In addition to this, all questions carry a rising intonation.

Myfarğaryls mimýaħ.

The man is sleeping.

Xemyfarğaryls mimýaħ? (read in a rising intonation)

Is the man sleeping?

These kind of questions may be answered by using a positive or negative of the main verb (myfarğaryls, 'is sleeping', for 'yes' or myfarğarylsíma, 'isn't sleeping' for 'no') or, more commonly, by using the positive or negative forms of the verb 'to be', in this case sils (is) for 'yes' and ixýma (is not) for 'no'. In Late Middle Ru, the adverb zw (thus, that way) also became a popular alternative for 'yes'.

Voice prefixes and valency operations

Middle Ru verbs may take a prefix that alters their valency (the number of arguments they require).

Valency-reducing operations

Transitive verbs ordinarily require a subject and an object. Middle Ru grammar provides mechanisms that allow the speaker to specify only one of these arguments, either for focus or in case the identity of the other argument is unknown or irrelevant.

Unspecific subjects

In order to omit the subject, no voice-marking prefixes are required; instead a null subject is expressed by using the pronoun ga which is treated as a class I third person noun for the purposes of verb conjugation. As with any other pronoun (Middle Ru being a pro-drop language), it is possible to drop ga, although speakers may want to include it to in order to unambiguously convey they refer to an unspecific subject rather than to a previously named class I referrent. The pronoun ga could be loosely translated as 'someone', although it might also refer to an inanimate or plural referent.

Compare:

Zevarñi ħox mimy.

The man (subject, mimy) sees the mountain (object, ħox).

to the ga equivalent:

Zevarñi ħox ga

Someone sees the mountain / The mountain is seen.

For ditransitive verbs such as ʎu (to give), this strategy only applies to the indirect object (the one expressed in the absolutive case). Thus, the full phrase

Λuwħåls xek'aħ mimy p'áñelt.

The man (subject, mimy) gave the stone (direct object, p'áñel) to the woman (indirect object, xek'a).

can have its indirect object focused as:

Λuwħåls xek'aħ p'áñelt (ga).

The woman was given a stone (by someone).

In order to promote the direct object p'áñel ('the stone was given [to the woman)'), the type-II applicative voice must be used.

Antipassive

All Middle Ru verbs are required to have a primary argument that would take the absoluitve case, even though this argument may be implicit. For transitive verbs, said argument corresponds to the [indirect] object. In order to omit the object and place a focus on the subject, the subject (originally found in the ergative case) must be promoted to the absoluitive role.

The antipassive voice, formed by using the prefix rrav- or rråv, turns a transitive verb into an intransitive verb which takes as its only argument the original subject. As in intransitive verbs, this sole argument must be expressed in the absolutive case, rather than in the ergative case as in the original transitive verb.

For example, the antipassive voice can be used to promote the subject and omit the original object in the following sentence:

Zevarñi ħox mimy.

The man (subject, mimy) sees the mountain (object, ħox).

which becomes:

Rravzevaryls mimýaħ.

The man sees [something].

Notices how the absolutive form mimýaħ is required in the latter sentence. It shoudl also be noted that the ending of the verb changed from -arñi (which indicates that the verb has an animate agent) to -aryls (which doesn't indicate an agent and is thus used for intransitive verbs).

This also applies to ditransitive verbs. In this case, the indirect object (the person to whom something is given) is omitted while the direct object (the thing that is given) may still be kept in the secundative case or dropped as the speaker sees fit.

Λuwħåls xek'aħ mimy p'áñelt.

The man (subject, mimy) gave the stone (direct object, p'áñel) to the woman (indirect object, xek'a).

becomes:

Rråvʎuwlws mimýaħ (p'áñelt).

The man gave (a stone).

Reflexive

The reflexive voice (marked with the prefixes my- or mw-) is used to indicate that the subject and object of a transitive verb are the same; that the action is done by 'to oneself'. Reflexive verbs are treated as intransitives grammar-wise:

Myzevaryls mimýaħ.

The man sees himself.

A limited number of verbs such as (my)farğ (to sleep) require a reflexive prefix:

Myfarğaryls mimýaħ.

The man sleeps.

**Farğaryls mimýaħ.

UNGRAMMATICAL

Verbs such as (my)farğ are only found without the reflexive prefix when a different voice mark is used on them. For instance, the causative form of the verb ('to make someone sleep') is ižyfarğ rather than the doubly-marked **ižymyfarğ.

Causative

Causatives, formed by using the prefixes ižy- or užw-, are used to express that someone (or something) triggers an action. This voice increases the valency of a verb, as a new argument (the one that causes the action) is added to the original arguments of the verb.

Unusually, the new argument (the causer) is expressed in the instrumental case. However, even though this was the norm for educated speakers following the standard found in the capital during the heyday of the Ru kingdom, evidence suggests that using the ergative case was widespread, especially for originally intransitive verbs. This was also reflected in the polypersonal markings found in verb suffixes: while the standard called for the polypersonal marking to be unaffected by the causative, in practice it was common for speakers to mark the causer as the agent of the verb.

Examples include:

C'azarmis emimýaħ.

The men march forward. (a sentence with an intransitive verb)

Ižyc'azarmis swrħúrwm emimýaħ.

The soldier made the men march forward. (causative; educated standard but uncommon in informal settings; ħúrwm, 'the soldier', is found in the instrumental case and the verb does not mark the causer as its agent)

Ižyc'azarmix emimýaħ ħúrwm.

The soldier made the men march forward. (causative; doesn't follow the standard but was ubiquitous in practice; ħúrwm, 'the soldier', is found in the ergative case and the verb does marks the causer as its agent)

Dåfwmås sujm rríxyat.

The bird ate seeds. (a sentence with a transitive verb)

Užwdåfwmås syrmimy sujm rríxyat.

The man make the bird eat seeds ~ The man fed the bird seeds (causative; educated standard; causer in the instrumental case, verb marks rríxy, 'bird', as its agent)

Užwdåfwmåx sujm rríxyat mimy.

The bird ate seeds ~ The man fed the bird seeds (causative; non-standard; causer in the ergative case, the same as the original subject rríxy, verb marks mimy, 'man', as its agent)

The causative cannot be applied when there is already a voice prefix (with the exception of lexically reflexive verbs such as farğ, 'to sleep', which in this context lose drop reflexive prefix instead). For instance, 'the woman made the man look at himself' couldn't be expressed with the causative voice prefix as 'the man [looked] at himself' would require the reflexive voice prefix. In these contexts, a periphrastic construction with the verb årmå (to cause, to force) may be used instead:

Årmåwħåñ xek'a, myzevilys mimýaħ.

The woman made the man look at himself (literally 'The woman caused (it), the man looked at himself ')

The verb årmå is also the source of a verb suffix -rm which is used for derivations with a causative meaning, as in forming darm (to remind) from da (to remember). This suffix, however, was no longer productive in Middle Ru and is only found in a very limited number of words.

Type-I applicatives may also fullfill a similar role to causatives, although with different nuances.

Type-I Applicative

Middle Ru has two applicative voices: prefixes which promote an oblique argument (one that ordinarily isn't the object nor the subject of the verb) to the primary position, the one marked with the absolutive case.

Type-I applicatives (marked with the prefixes ke- and ko-) are used to promote an argument in a benefactive role, this is, a person for whom an action, that benefits from the situation. Unlike causatives, this object does not need to have caused or be otherwise involved in the action, but it will get a benefit from it. For instance the sentence:

Kecavdimax oħúrwmaħ mimy séket.

"The man cut the trees for the soldiers."

does not imply that the soldiers forced or even ordered the man to cut the trees but rather implies that the man did it on his own in order to ease their march. This contrasts with the causative form ižycavdimax swroħúrwm sek mimýaħ (the soldiers made the man cut the trees) where it could be assumed that the soldiers played an active role in having the man cut the tree.

In a type-I applicative, the benefited argument takes the absolutive case, while the argument that hold that position before (the object in a transitive verb or the subject in an intransitive verb) takes the secundative case instead, as seen in séket, the secundative form of sek (trees). The secundative argument may be dropped as in the following example:

Kocwñimax oħúrwmaħ mimy.

The men built for the soldiers.

This could be short for kocwñimax oħúrwmaħ mimy k'ételt (the soldiers built a house for the soldiers), but puts the focus on the action the men undertook in benefit of the soldiers rather than on the result (what they did build for them).

Type-I applicatives may not be used with ditransitive verbs such as ʎu.

Type-II Applicative

Type-II applicatives (formed with the prefixes aj- and oj-) are used to promote a direct object of a a ditransitive verb to the primary absolutive role, originally occupied by the indirect object. Consider the phrase:

Λuwħåls xek'aħ mimy p'áñelt.

The man (subject, mimy) gave the stone (direct object, p'áñel) to the woman (indirect object, xek'a).

As it has been mentioned before, this phrase on its own takes the indirect object (the woman) as its primary argument. This allows a speaker to construct a sentence when only this argument is specified (arguments in brackets are optional):

Λuwħåls xek'aħ [ga] [p'áñelt].

The woman was given [the stone] [by somebody].

In order to do the same with the subject, the antipassive voice is needed, which moves the subject (originally marked in the ergative case) to the primary role:

Rråvʎuwlws mimýaħ [p'áñelt].

The man gave [the stone].

Type-II applicatives allow the speaker to do the same with the direct object (in this case, the object that is given to someone), which is promoted to the primary role and, as such, takes the absolutive case rather than the secundative:

Ojʎuwħañ p'áñel [mimy].

The stone was given [by the man].

The verb stem

The stem is the main morpheme that decides the meaning of the verb. A MIddle Ru verbal stem will always occur with at least one suffix although they will be listed on their most basic form in the dictionary..

Verb stems whose romanized forms seem to end in a vowel, such as da (to remember) actually have a glottal coda (unwritten between vowels): /da.ʔ/, as seen in the conjugated form daiħaŋ (I remembered it): /da.ʔiˈχaŋ/. This is still the case when the vowel in the suffix coincides with the last vowel in the stem, as in daarxes (you remember me): /da.ʔaɹˈʃøs/, although a relatively small number of speakers might have contracted these sequences to a bare vowel (yielding */daɹˈʃøs/ for da[a]rxes). It should be noted that contracting /V.ʔV/ to /V/ is a nearly universal phenomenon for nouns (for instance, the ergative form of c'áza is c'azat rather than **c'azaat). The absence of contractions in verbs might be a result of Middle Ru speakers considering the glottal stop as being part of the verb root itself rather than an artifact of the language's phonology as in nominal affixes.

Incorporated nouns

Middle Ru grammar allows nouns to be incorporated into verbs although this feature is not used as widely as in other polysynthetic languages.

In order to incorporate a noun into a verb, the base form of the noun (with no number nor case affixes) is added after the verb stem. A connecting affix -ö- (-e- or -o- depending on the vowel harmony class of the incorporated noun) is used except for vowel-initial nouns. For instance, incorporating the vowel-initial noun áɣa (land, dirt) to the verb myjt (to cover) results in forms such as myjtaɣaiħárga (I covered it with dirt ~ I buried it) while incorporating qana (family) to hwn (to rule) yields forms such as hwneqanaarmat (you belong to the ruling dynasty, literally 'you family-rule them'), with an extra e connecting the two words. It should be noted that incorporated nouns might belong to the opposite vowel harmony class as in the latter example (hwn being a dark-class verb while qana is a clear-class noun). In these cases, all suffixes occurring after the noun belong to the same harmony class as the noun. Because of this, we find the clear-harmony affixes -armat in hwneqanaarmat but their dark-harmony counterparts -årmåt when no noun is incorporated to the verb: hwnårmåt (you rule over them).

Incorporated nouns most commonly indicate an instrument or material used to perform an action. For instance, 'the city was built with stone' could be translated as cwñep'añeiħañ ɣen, literally 'they stone-built the city', incorporating p'áñe (stone) into the verb cwñ (to build). This kind of sentences, however, might also be expressed with the instrumental case as in cwñwħåñ ɣen syrp'áñe (literally 'they built the city with-stone') and the latter usage seems to have been favoured in official Cadarmeni documents. Incorporated nouns might also be used to indicate generic direct objects as in qyt'ek'et'aiħañ for 'they harvested rice' (incorporating k'ét'a, 'rice', into the verb qyt', 'to harvested') although this seems to have been limited to a few idiomatic examples.

Additionally, noun incorporation would occasionally yield phrases with an a priori unexpected idiomatic usage. As seen before, hwn (to rule) plus qana (family) yielded a verb that meant ' to belong to the ruling family'. A more systematic example is the usage of qurt (hands) to indicate that an action is done by oneself. For instance cavdoqurtwħåñ sek mimy, literally 'the man hand-cut the trees' will typically imply that the man cut all the trees 'by himself' rather than doing it 'by hand'. Qurt can be incorporated into a verb with a more literal meaning, however: dåfoqurtårmås (incorporating qurt to dåf, 'to eat') would be more likely to be understood as meaning 'I was eating them using my hands (not cutlery)' than 'I was eating them on my own'.

Aspect

Although in Middle Ru aspect-marking is fused with tense marking and personal agreement in the final suffix of the verb (aside from the negative suffix), aspect-marking proto-morphemes can be easily identified, even though their form may vary slightly depending on the following tense suffix. In general, it can be identified that the suffixes -ar- and -år- are used for the imperfective aspect, -iħ- and -wħ- are used for the perfective aspect while -iis- and -ujws- are used for the inchoative aspect.

Changes found in those base aspect affixes include:

- The r (/ɹ/) in the imperfective suffixes is lost before tense+person markers which begin with alveolar trill rr (/r/). Some speakers may also drop that r before the uvular trill rg (/ʀ/) although this seems to have been proscribed in the Cadarmeni standard.

- The final ħ of perfective suffixes and the final s of inchoative affixes are dropped before any tense+person marker with an initial vowel.

The following table illustrates the various forms aspect affixes may take for each vowel-harmony class under different circumstances.

| Aspect | Vowel harmony class |

Shape of the tense affix | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vowel initial | Rhotic initial | Other | |||||

| Aspect affix |

Example: -aq / -åq (1s.PST) |

Aspect affix |

Example: -rra / -rrå (1s>3sA.PST) |

Aspect affix |

Example: -lys / -lws (3sA.PST) |

||

| Imperfective | Clear | -ar- | -araq | -a- | -arra | -ar- | -arlys |

| Dark | -år- | -åråq | -å- | -årrå | -år- | -årlws | |

| Perfective | Clear | -iħ- | -iħaq | -i- | -irra | -i- | -ilys |

| Dark | -wħ- |

-wħåq | -w- | -wrrå | -w- | -wlws | |

| Inchoative | Clear | -iis- | -iisaq | -ii- | -iirra | -ii- | -iilys |

| Dark | -ujws- | -ujwsáq | -ujw- | -ujwrrå | -ujw- | -ujwlws | |

Perfective and imperfective

The perfective aspect is used to indicate an action that ocurred at a given point in time which may be used as a reference for further actions. On the other hand, the action described by an imperfective verb takes place during a period of time, set in relation to certain reference point which might be the present (for a verb marked as having the non-past tense) or the point in time set by a perfective verb.

In the past-tense, the distinction between perfective and imperfective is verbs is analogous to the one found in Spanish and approximately corresponds to the distinction between simple past and past progressive (or past continuous) in English:

Zevisax.

see-PRFV-1s>2s.PST

I saw you / I've seen you (Spanish perfective past te vi)

Zevarsax.

see-IPFV-1s>2s.PST

I was seeing you, I saw you [during that time] (Spanish imperfective past te veía)

The non-past tense is most commonly found along the imperfective aspect in order to express events that take place at the present:

Zevarsix.

see-IPFV-1s>2s.NPST

I see you, I am seeing you.

Non-past tense-endings are used along perfective affixes in order to indicate an action or event that has not taken place. This covers both sentences concerning the future as well as hypothetical situations.

Zevisix [múnå].

see-PFV-1s>2s.NPST [tomorrow]

I will see you [tomorrow]

Zevisix, kaj zeviħyxet.

see-PFV-1s>2s.NPST therefore see-PFV-2s>1s

If I saw you (hypothetical) then you would see me

It should be noted that the primary meaning of the perfective and imperfective affixes is still a matter of whether the event can be thought as establishing a reference in time (as it is the effect when using a perfective) or extending over a period fixed to an existing reference frame (which might be either the present or a time frame previously referenced through a perfective). Thus, while non-past imperfectives would commonly translate as present-tense verb in English, they might also refer to an event which takes place concurrently with another event in the future, as it's the case for the second verb in this sentence:

Zevisix múnå, sw savarŋi!

see-PFV-1s>2s.NPST tomorrow then regret-IPFV-2s>3sI.NPST

I will see you tomorrow and then you will regret it

Inchoatives and cessatives

The affixes -ii(s)- and -ujw(s)- are used to indicate the onset of an action or state; that the action is beginning. This onset might have happened in the past (in which case in inchoactive affix is to be used with a past-tense marker) or in the present or future (for which non-past endings are used):

Cavdiisañ sek mimy.

cut-INCH-3sA>3si.PST tree man

The man began to cut down the trees.

Cavdiiñi sek mimy.

cut-INCH-3sA>3si.NPST tree man

The man begins to cut down the trees.

One particularity of Middle Ru's inchoative affix is that it becomes a cessative (indicating the end of an action) when the verb is marked as negative. Thus, negating the previous examples yields:

Cavdiisañíma sek mimy.

cut-INCH-3sA>3si.PST.NEG tree man

The man stopped cutting down the trees.

Cavdiiñiʎíma sek mimy.

cut-INCH-3sA>3si.NPST-NEG tree man

The man stops cutting down the trees.

In order to truly negate an inchoative (indicating that the event didn't begin, rather than it stopped) the adverb eʎíma (roughly translatable as 'not yet') may be used after the verb. The same can be done for cessatives (ie verbs with the inchoative affix already marked as negative):

Cavdiisañ eʎíma sek mimy.

cut-INCH-3sA>3si.PST.NEG not_yet tree man

The man didn't start cutting down the trees [yet].

Cavdiisañíma eʎíma sek mimy.

cut-INCH-3sA>3si.PST.NEG not_yet tree man

The man didn't stop cutting down the trees [yet].

Tense and person

The final mandatory affix in a Middle Ru verb encapsulates information about its tense (in a past vs non-past contrast that was exemplified in the preceding section) and its arguments, potentially including hints at both its subject and its object. These affixes are fusional in nature: although its Proto Ru-Hulam etymology might hint at which phonemes stood for each category and despite the fact that some of those patterns can still be observed to some degree in Middle Ru affixes (while others have eroded past recognizability), these final affixes cannot be broken into separate tense, subject and object markers but form a single unit that might express all three categories. For instance, the suffix -yxet can be considered a single unit marking the verb as having non-past tense, a second person agent role (subject) and a first person singular object role rather than a sequence of marker for each of those categories.

Each tense×person (or TP) affix marks a tense (non-past or past) and a person for the verb's O-role, the one that would take the absolutive case (that is, the subject for an intransitive verb, the object for a transitive verb and the indirect object for a ditransitive verb). A TP affix may also include information about the verb's A-role, which corresponds to the subject in transitive and ditransitive verbs; the argument generally marked with the ergative case in Middle Ru's grammar. Grammatical persons are expressed differently for each role; for instance O-role marking accounts for number while A-role marking doesn't.

Affixes that are not marked for any A-role are used for intransitive verbs, reflexive verbs (marked with the reflexive prefix my- or mw-) as well as for transitive/ditransitive verbs whose A-role corresponds to an ininamiate third person referent ('it', or an inanimate 'they'); as in the following examples, all of which use the affix -aq / -åq, which marks past-tense, the first person singular (I, me) as its O-role and leaves the A-role unmarked:

C'aziħaq.

I marched (intransitive verb; the O-role indicates the subject)

Myzeviħaq.

I saw myself (reflexive verb; the O-role indicates the argument that is simultaneous the object an the subject)

Bruswħåq!

It crushed me! (transitive verb; the O-role indicates the object, the subject is an inanimate third person referent, 'it')

Certain combinations of O-roles and A-roles are not allowed. This occurs whenever the O-role coincides with the A-role or when the A-rule refers to a group that includes the O-role (for instance if the A-role was 'inclusive we' and the O-role was 'I' or 'you').

The affixes, in both its vowel-harmony variants, are as follows:

| NON-PAST TENSE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-role: | 1s, me | 2s, you | 3s.ANIM | 3s.INAN | 1p (exclusive) | 1p (inclusive) | 2p or 3p |

| A-role: | |||||||

| Unmarked, reflexive or inanimate third person |

-yk -wk |

-is -us |

-yls -wls |

-ñi -ñw |

-mirri -murru |

-ŋyr -ŋwr |

-mis -mus |

| 1s or 1p.EX |

(not used) |

-six -sux |

-ýrra -ẃrrå |

-árgy -ǻrgu |

-ŋyx -ŋwx |

-mik -muk |

|

| 1p.IN |

(not used) | (not used) | -rgi -rgu |

(not used) | (not used) | ||

| 2s or 2p | -yxet -wxot |

(not used) | -ils -uls |

-ŋi -ŋu |

-miz -muz |

(not used) | -mit -mut |

| 3s.ANIM or 3p.ANIM |

-yx -wx |

-it -ut |

-ylx -wlx |

-ñi -ñw |

-mírra -múrrå |

-ŋyr -ŋwr |

-mix -mux |

| PAST TENSE | |||||||

| O-role: | 1s, me | 2s, you | 3s.ANIM | 3s.INAN | 1p (exclusive) | 1p (inclusive) | 2p or 3p |

| A-role: | |||||||

| Unmarked, reflexive or inanimate third person |

-aq -åq |

-as -os |

-lys -lws |

-aŋ -åŋ |

-mir -mur |

-ŋir -ŋur |

-mas -mås |

| 1s or 1p.EX | (not used) | -sax -såx |

-rra -rrå |

-árga -ǻrgå |

-aŋak -åŋåk |

-mak -måk |

|

| 1p.IN | (not used) | (not used) | -árxa -ǻrxå |

(not used) | (not used) | ||

| 2s or 2p | -xes -xos |

(not used) | -ílsy -úlsw |

-aŋy -åŋw |

-mas -mås |

(not used) | -mat -måt |

| 3s.ANIM or 3p.ANIM |

-ax -åx |

-at -åt |

-als -åls |

-añ -åñ |

-mir -mur |

-ŋir -ŋur |

-max -måx |

It should be noticed, however, that some of these affixes might appear in a modified when used along the negatives suffix, as it shall be explained in the following section.

Negatives

Negative verbs are marked with an additional suffix whose shape depends on the TP affix of the verb. It should be noted that negative constructions alter the semantics of inchoative verbs, as discussed on the previous section about that aspect.

The base form of the negative suffix is -ʎíma for words in the clear vowel-harmondy class and -ʎúmå. This form is used to negate verbs which would otherwise end in a vowel:

Zevarýrra mimýaħ.

I see the man.

Zevaryrraʎíma mimýaħ.

I do not see the man.

Verbs whose TP affix ends in a /k/ or a /q/ lose that final consonant and get modified suffix -ʕíma or -ʕúmå:

Zevimak emimýaħ.

I saw the men.

Zevimaʕíma emimýaħ.

I did not see the men.

Verbs whose TP affix ends in any other consonant get the reduced negative affixes -íma or -ýmå:

Zevarmix.

I see you.

Zevarmixíma.

I do not see you.

Other verb forms

While most verbal inflections conform to the previously described sequence of affixes (interrogative-voice-stem-tool-aspect-TP-negative), there is a limited number of inflectional forms that follows a different structure. This is true for imperatives and participles.

Imperatives

There exist two ways to issue a command in Middle Ru: using what is known as a true imperative or by using a periphrastic construction known as the humble imperative.

True imperatives are used whenever both speakers have a similar social status or if it is the one issuing the command who has a higher status. These verbs only deviate from the general conjugation structure in the fact the aspect and TP affixes are replaced with the suffixes -avt or -ot for positive commands or -eʎimavt or -oʎumot for negative commands. Contrary to what is typically found in the language, Middle Ru true imperatives could be said to have a nominative-accusative alignment, as the person receiving the imperative is intended the take the subject role both in intransitive and transitive verbs. Commands related to other roles may be issued by using voice affixes as described in the table below. It should be noted that Middle Ru true imperatives are not marked for person and thus independent pronouns are more likely to be necessary.

| Voice | Imperative role | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active (default) Intransitive verb |

Subject (O-role, absolutive) |

C'azavt! | March forward! |

| Active (default) Transitive verb |

Subject (A-role, ergative) |

Zevavt ña! | Look at that! |

| Antipassive | Not used for true imperatives | ||

| Reflexive |

Reflexive argument, (subject and object) |

Myzevavt! | Look at yourself! |

| Object (O-role, absolutive) | Myevavt hev! | Be seen by the king! ~ Let the king see you! |

|

| Causative | Causative agent |

Ižyc'azavt emimy! | Make the men march! |

| Type-I applicative |

Not used for true imperatives | ||

| Type-II applicative |

Theoretically used for direct objects of ditransitive verbs, but never found in practice. |

||

Humble imperatives, on the other hand, are formed periphrastically by using a regularly-conjugated form of the verb har, 'to ask' followed by the desired action. As the name for this construction suggest, humble imperatives are mostly used in situations where the speaker might have a lower social status than the listener, and thus asks them humbly rather than imposing their command with a true imperative. The verb har will be typically found as hararsix for orders issued to a singular you or hararmik for imperatives issued to a plural you. These verbs would be negated as usual, resulting in hararsixíma and hararmiʕíma for 'I did not ask you [to]'. The following table shows the humble equivalents to the previous examples assuming the command is issued to a single person (otherwise verbs would be conjugated for 2p instead of 2s):