Brytho-Hellenic: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

!'''Letters''' | !'''Letters''' | ||

!'''Pronunciation''' | !'''Pronunciation''' | ||

!''' | !'''Notes''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

|a | |a | ||

| Line 613: | Line 613: | ||

Brythohellenic has no ''indefinite article''; to translate phrases like "a cat" or "some women" we have just to omit the article: '''ailur''' means both "a cat" and "cat", and '''ginais''' means both "some women" and "women". | Brythohellenic has no ''indefinite article''; to translate phrases like "a cat" or "some women" we have just to omit the article: '''ailur''' means both "a cat" and "cat", and '''ginais''' means both "some women" and "women". | ||

There is only one kind of article, the ''definite'' one: this article is used to | There is only one kind of article, the ''definite'' one: this article is used to refer to well known things that are familiar to the speakers, because they have already been talked about, or in orderto invoke the known experience of the speakers. That is, we use the definite article to talk about known information. | ||

The definite article has one invariable form, '''to''', that is used both for masculine and feminine nouns, for singular and plural nouns: '''to omyr''', "the rain"; '''to huvagh''', "the body"; '''to lusai''', "the languages"; '''to nysoi''', "the islands", and so on. | The definite article has one invariable form, '''to''', that is used both for masculine and feminine nouns, for singular and plural nouns: '''to omyr''', "the rain"; '''to huvagh''', "the body"; '''to lusai''', "the languages"; '''to nysoi''', "the islands", and so on. | ||

| Line 1,299: | Line 1,299: | ||

====Indefinites==== | ====Indefinites==== | ||

Indefinites give us incomplete | Indefinites give us incomplete information, because they don't define the precise quantity or the identity: | ||

{| {{Table/bluetable}} style="text-align:center; vertical-align:middle" | {| {{Table/bluetable}} style="text-align:center; vertical-align:middle" | ||

Revision as of 02:08, 17 May 2015

This article is private. The author requests that you do not make changes to this project without approval. By all means, please help fix spelling, grammar and organisation problems, thank you. |

| Brytho-Hellenic | |

|---|---|

| Elynic (to cain) | |

| Pronunciation | [[w:Help:IPA|ɛ'li:nik 'tɔ 'kai̯n]] |

| Created by | – |

| Native to | Elas to Cain |

| Native speakers | 52 million (2012) |

Indo-European

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Elas to Cain |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | el |

| ISO 639-2 | ely |

| ISO 639-3 | ely |

New Greece or "Elas to Cain" | |

General information

Brytho-Hellenic, Brythohellenic or simply Neohellenic (the native name is Elynic) is a language that is spoken nowadays in a different timeline in a country that corresponds almost exactly to our England and to our Wales. In that timeline the Persians won the wars against Greece and the Greeks were forced to emigrate and to flee. Firstly the Greeks find protection in Magna Graecia, but, as the Persians conquer those territories, they shift to Northern Italy, where the Romans withstand the Persian troops. In 389 b.C. Rome is destroyed and both Romans and Greeks flee to Carthage, enemy of the Persian empire. Together they try to attack the Persian fleet, but they are defeated again. In the last days of 382 b.C. an imposing expedition sails away from a harbour on the coast of New Carthage - our Cartagena in Spain. Its mission is to find new territories where they can live in peace and prosperity, far from the Persian threat. In 381 b.C. Conon the Athenian and his Greeks reach our Scilly Islands: they chose to sail northward, because they had heard about legends that spoke about a fertile and grassy island in the North. It is the beginning of the New Greece or Elas to Cain (IPA ['ɛlas 'tɔ 'kai̯n]).

Phonology

Alphabet

After the defeat against the Persians almost the entire Greek people fled towards Roman territory: Rome triplicated its population and was greekized. During their living together Greeks and Romans used mainly the Greek language to communicate, whereas the Latin language became a secondary and socially lower language, spoken mainly by common people. Nevertheless - almost incomprehensibly - the Greeks adopted the Latin alphabet, maybe trying to be understood even by the lower social classes. As we are talking about the modern language, we don't consider the first versions of the alphabet that were used in ancient times. The alphabet of Brythohellenic contains 24 letters:

| Letters | Pronunciation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| a | [a] | it is an opened central vowel |

| b | [b] | - |

| c | [k] | it is always pronunced as in the English word cat, even in front of e, i, and y |

| ch | [x] | it is pronounced as in the Scottish word loch |

| d | [d] | - |

| dh | [ð] / [j] / [v] / [ ] | generally it is pronounced as th in the word this; when it occurs between vowels its pronunciation can vary between [j] and [v]: generally it is [j] when the vowel that follows is e, i or y, while it is [v] when the vowel that follows is a, o or u. Some speakers don't pronounce it at all when it comes between two back vowels. At the very end of a word or before a consonant it is generally pronounced as [ɣ] and it is written as gh in this case. |

| e | [ɛ] / [e] | it can be pronounced either open or closed, this doesn't affect the meaning of words |

| f | [f] | - |

| g | [g] | it is always pronounced as in the English word gun, even in front of e, i, and y |

| gh | [ɣ] | it is the variant spelling of a word final dh. It can only appear at the end of a word. |

| h | [h] | - |

| i | [i] / [j] | often it forms a diphthong when precedes or follows another vowel |

| l | [l] | - |

| m | [m] | - |

| n | [n] | - |

| o | [ɔ] / [o] | it can be either open or closed, but it doesn't affect the meaning |

| p | [p] | - |

| r | [r] | trilled just as in Italian |

| s | [s] | always voiceless |

| t | [t] | - |

| th | [θ] | as th in the English thin |

| u | [u] / [w] | it is pronounced as [u] when it is followed by a consonant; it is pronounced [w] when it is preceded or followed by a vowel |

| v | [v] | - |

| y | [i:] | it is pronounced like e in the English word see. |

Consonantal phonemes

Brythohellenic has the following consonantic phonemes:

| Phonemes | Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | p b | t d | k g | |||||

| Affricate | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | (ɱ) | n | (ŋ) | ||||

| Fricative | f v | θ ð | s | x | h | |||

| Approximant | r̥ r | j | w | |||||

| Lateral approximant | l |

Vocalic phonemes

Brythohellenic has the following vowel system:

| Phonemes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Opening | Front | Back |

| Closed | i | u |

| Mid-closed | e | o |

| Mid-open | ɛ | ɔ |

| Open | a | |

There is also the schwa sound [ǝ]. The natives don't consider it a distinct sound, though, and as it occurs specially at the end of words where it is written an a, they consider it to be a true 'a'!

Diphthongs and digraphs

In Brythohellenic there are 17 diphthongs, that is clusters of two vowels pronounced with a single emission of air. These diphthongs are:

| Diphthongs | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| ai | [ai̯] |

| au | [au̯] |

| ei, ey | [ɛi̯] / [ei̯:] |

| eu | [ɛu̯] |

| ia | [ja] |

| ie | [jɛ] / [je] |

| io | [jɔ] / [jo] |

| iu | [ju] |

| oi | [ɔi̯] / [oi̯] |

| ua | [wa] |

| ue | [wɛ] / [we] |

| ui | [wi] |

| uo | [wɔ] / [wo] |

| uy | [wi:] |

| yu | [i:u̯] |

The use of dieresis indicates that the combination of vowels is to be read as a hiatus, f.ex.: süae, lives, is read as ['suai̯], it is thus a two-syllable word. Brytho-Hellenic has only one digraph: rh [r̥], which is rare enough. The other combinations as ch, dh/gh, and th are considered true letters.

Stress

Ancient Greek has undergone deep changes during its coexistence with Latin and above all with the Brythonic languages. Two main changes have been:

- often the hiatus with 'i' has become a diphthong, ex.: σοφία > *σόφια > hef, "knowledge";

- almost always the last syllable was dropped, ex.: καινός > cain, "new"; θάνατος > thanagh, "death".

These two phoenomena have influenced heavily the stress system of Brythohellenic. Nowadays the stress steadily falls on the last but one syllable: this means that in the plural forms of nouns it shifts, ex.: thalas ['θalas], "sea" > thalasas [θa'lasas], "seas"; ailur ['ai̯lur], "cat" > ailuroi [ai̯'luroi̯], "cats".

Sometimes the accent falls on the last syllable, above all in some verbal forms. In these cases an acute accent is written on the accented vowel, ex.: emén nüi [e'men:ui̯], "we are"; acú eu [a'ku eu̯], "I hear". The written accent can also distinguish two words that are written the same but have different meanings, ex.: y, "than", ≠ ý, "she".

Grammar

Nouns, gender and number

Though Ancient Greek had three genders and three numbers, the system simplified greatly and Modern Elynic has two genders - masculine and feminine - and two numbers - singular and plural. It is hard to distinguish the gender of a noun, because there are not specific gender-linked endings: mostly nouns end with consonant regardless for the gender. Forming plural is not so complicated, as there are only three plural endings:

- oi, that is typical of masculine nouns;

- ai, that is used with feminine nouns;

- as, less spread and used with both masculine and feminine nouns.

Please note that nowadays the endings oi and ai tend to be replaced with the colloquial e both in writing and speech. The same occurs with the endin as, that is substituted for es. These endings, that come from South-Elas dialects, are less used in the North. There are also some irregularities which have to be learned by heart, ex.: the plural of ith, "fish", is ithuas; the plural of gys, "earth", is gai; the plural of ur, "water", is udhas, and so on. Irregular nouns, however, are few. Here is a list of nouns with plural form:

| Singular | Plural | Gender | Meaning | Singular | Plural | Gender | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ligh | lidhoi | masculine | stone | pud | pudas | masculine | foot |

| cur | curai | feminine | land | uran | uranoi | masculine | sky, heaven |

| cryvid | cryvidas | feminine | shoe | fus | fudhas | masculine | light |

| süy | süai | feminine | life | lus | lusai | feminine | language |

| thyr | thyras | masculine | animal | bivel | bivloi | masculine | book |

| erugh | erudhas | masculine | love | aluvec | aluvecai | masculine | fox |

| coiran | coiranoi | masculine | lord | coiren | coiranai | feminine | lady |

| enyr | anras | masculine | man | ginys | ginai | feminine | woman |

| pir | piroi | masculine | fire | cefel | cefalai | feminine | head |

| tov | tovoi | masculine | place | cron | cronoi | masculine | time |

| odher | odhroi | masculine | morning | yver | yverai | feminine | day |

| dyl | dylai | feminine | afternoon | efer | eferai | feminine | evening |

| nith | nithas | feminine | night | hilyn | hilynai | feminine | moon |

| celgh | celdhoi | masculine | priest | cilgh | celdhai | feminine | priestess |

| dennyr | dennyras | masculine | tree | cagh | cadhas | masculine | hand |

| etyr | eteras | masculine | star | omagh | omadhas | masculine | eye |

| cedhygh | cedhydhas | masculine | teacher | fil | filoi | masculine | friend |

| ether | ethroi | masculine | enemy | edhair | edhairoi | masculine | lover |

| cïun | cinoi | masculine | dog | com | comoi | masculine | world |

Loan words

As the Greeks reached Great Britain found a completely new world, full of animals and plants they had never seen. Celtic people had highly different customs and beliefs and spoke an unintelligible language. Even if the Greeks considered them to be barbarian, they were the "owners" of the new land, so Greeks had to learn to live together with Brythons and to forget about prejudices like "superiority" or "inferiority". During the coexistence and the mixing with Brythons, the Greeks have adopted some Celtic words coming from Brythonic and that can be compared with words of our modern Celtic languages:

| Comparable with | Singular | Plural | Gender | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| derwen | daruen | daruenai | feminine | oak |

| derwydd | daruigh | daruidhas | masculine | priest, magician, druid |

| bryn | bryn | brynai | feminine | hill |

| nifwl | nivul | nivuloi | masculine | mist, fog |

| llyn | lyn | lynoi | masculine | lake |

| gwellt | guell | guellas | feminine | grass |

| ofydd | evigh | evidhas | masculine | ovate |

| bardos | bard | bardas | masculine | poet |

| awen | auen | auenai | feminine | inspiration |

| bleydh | bleigh | bleidhas | masculine | wolf |

| lowarth | louarth | louarthas | feminine | paradise |

| calon | calen | calenai | feminine | heart |

Some words have a counterpart whose meaning has shifted: from the Greek ουάτις, a word mentioned by Strabo and of Proto-Celtic origin (*vatis), comes guegh, "astute person" < "one who can predict the moves of enemies" < "soothsayer". From the same root comes of course the Brythonic word *oveð (> W. ofydd), that has been borrowed once the Greeks reached Great Britain. Another example is the word bard, that has substituted the Ancient Greek ἀοιδός, whose descendant, auid, has the meaning of "artist". Even the word auen has substituted another Greek word, daivon < *δαιμόνος < δαιμόνιον, that now has the meaning of "puck, spirit"; the plural Auenai is also used to mean Musai, plural of Mus < Mοῦσα, "Muse".

Formation of feminine

It isn't easy to distinguish between a masculine and a feminine noun, because there is no gender-linked ending. However, when we speak about entities that have a physical gender, such as people and animals, it can be useful to be able to distinguish between masculine and feminine gender. Mostly the feminine form of such nouns come from the masculine one by adding some suffixes:

- -er (pl. -(e)rai), mostly added to masculine nouns ending with -ydh and denoting agent, ex.: melbygh (= "singer") > melbydher (plural: melbydhrai);

- -en (pl. -anai), added to many nouns, ex.: ether > ethren (plural: ethranai); fil > filen (plural: filanai);

- -e- (pl. -a-ai), that replaces the ending a + consonant of many masculine nouns, ex.: elaf (= "deer") > elef (plural: elafai); mau (= "sorcerer") > meu (= "witch") (plural: mauai).

Sometimes the feminine form is obtained by changing the last vowel, ex.: celgh > cilgh (plural: celdhai).

Articles

Brythohellenic has no indefinite article; to translate phrases like "a cat" or "some women" we have just to omit the article: ailur means both "a cat" and "cat", and ginais means both "some women" and "women". There is only one kind of article, the definite one: this article is used to refer to well known things that are familiar to the speakers, because they have already been talked about, or in orderto invoke the known experience of the speakers. That is, we use the definite article to talk about known information. The definite article has one invariable form, to, that is used both for masculine and feminine nouns, for singular and plural nouns: to omyr, "the rain"; to huvagh, "the body"; to lusai, "the languages"; to nysoi, "the islands", and so on.

When a noun is determined, that is preceded by the article or other determiners (such as possessives or demonstratives) and is followed by an adjective - in standard Elynic the adjectives always follow the substantives - the article shifts bewtween noun and adjective, ex.:

- to omyr > omyr to sirin (= "the cold rain", lit. "rain the cold (one)");

- to nysoi > nysoi to eivedhoi (= "the fertile islands", lit. "islands the fertile (ones)").

Even when a noun doesn't need the article - for example proper nouns - it appears between this noun and the possible adjective, ex.:

- Elas (= "Greece") > Elas to Cain (= "New Greece", lit. "Greece the New (one)");¹

- Elyn (= "Helena") > Elyn to plyd calin (= "the most beautiful Helena", lit. "Helena the most beautiful (one)").

¹ Nowadays they tend to use the word Elas to mean Elas to Cain, while the "Old Greece" is known as Elas to Palagh.

Adjectives

Elynic adjectives always follow the noun(s) they are referred to: when the noun is undetermined they simply follow it, but, when the noun is determined, then the definite article, to, or the possessives are put between the noun and the adjective. Usually adjectives' singular form is identical for masculine and feminine, even if there can be exceptions, the plural forms are two, instead: one for masculine, usually ending in -oe, and one for feminine, ending in -ae. Some adjectives:

| Singular | Masculine plural | Feminine plural | Meaning | Singular | Masculine plural | Feminine plural | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ivygh | ivydhoi | ivydhai | good | penyr | penyroi | penyrai | bad |

| elev | elvoi | elvai | happy | lir | liroi | lirai | sad |

| egrin | egrinoi | egrinai | tall / high | thaval | thavaloi | thavalai | short |

| calin | calinoi | calinai | beautiful / goodlooking | aiger | aigroi | aigrai | ugly |

| meal | mealoi | mealai | big / great | migrin | migrinoi | migrinai | little / small |

| palagh | paladhoi | paladhai | old | yvic | yvicoi | yvicai | young |

| thenar | thenaroi | thenarai | strong | athin | athinoi | athinai | weak |

| thervin | thervinoi | thervinai | hot | sirin | sirinoi | sirinai | cold |

| fover | foveroi | foverai | terrible | plys | plysoi | plysai | near / close |

| tyledhin | tyledhinoi | tyledhinai | far / distant | semyc | semycoi | semycai | tired |

Some usage examples:

- migrin + ailur > ailur migrin (= "(a) little cat");

- meal + to enyr > enyr to meal (= "the big man");

- semyc + coiren evon > coiren evon semyc (= "my tired lady").

Comparative

The higher degree comparative is usually formed with the word va that precedes the adjective to which is referred, the second term is introduced by y ex.:

- Angh va calin y dennyr > A flower more beautiful than a tree.

In the written language it is still used the old form with the suffix -un, ex.:

- Angh caldhun y dennyr > A flower more beautiful than a tree.

The same degree comparative is formed with the periphrasis udhys + adjective + yfer, ex.:

- Angh udhys calin yfer dennyr > A flower as beautiful as a tree,

The lower degree comparative is formed with the periphrasis myon + adjective + y, ex.:

- Angh myon calin y dennyr > A flower less beautiful than a tree.

Adjectives with an irregular higher degree comparative

Some adjectives have an irregular form of higher degree comparative:

| Positive | Comparative | Positive | Comparative |

|---|---|---|---|

| ivygh | aredhun | penyr | ysun |

| calin | caldhun | red (= "easy") | raun |

| migrin | medhun | meal | mysun |

| polis (= "many/much") | pledhun | aluyn (= "painful/agonizing") | aldhun |

Irregular higher degree comparatives are used as normal comparatives, ex.:

- Ys hi aredhun y eu - You are better than me.

The comparative form is the same for both masculine and feminine nouns, but in the plural the two forms are different: aredhunoi vs. aredhunai.

Superlative

The superlative degree is generally formed with the word plyd, that precedes the adjective to which is referred. The relative superlative is the same form of the absolute superlative, but it takes the definite article and is generally followed by a limitation, that is expressed with en (= "in") / evan (= "of"), ex.:

- Angh to plyd calin en to com - The most beautiful flower in the world.

In the written language it is also used the old superlative with the suffix -yd:

- Angh to calyd evan to com - The most beautiful flower of the world.

Adjectives with an irregular superlative

The same adjectives that have an irregular higher degree comparative have also an irregular superlative form:

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative | Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ivygh | aredhun | aryd | penyr | ysun | ycyd |

| calin | caldhun | calyd | red | raun | rad |

| migrin | medhun | elegyd | meal | mysun | meyd |

| polis | pledhun | plyd | aluyn | aldhun | aluyd |

Other adjectives form the comparative and the superlative degree regularly, ex.:

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

|---|---|---|

| palagh | va palagh / paladhun | plyd palagh / paladhyd |

| lir | va lir / lirun | plyd lir / liryd |

| egrin | va egrin / egrinun | plyd egrin / egrinyd |

| plys | va plys / plysun | plyd plys / plysyd |

The superlative has only one singular form, in the plural masculine and feminine are different, ex.: aryd > arydoi, arydai.

Numerals

Numerals don't inflect. Here are the numerals from 0 to 100:

| Number | Cardinal | Ordinal | Number | Cardinal | Ordinal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | uden | - | 1 | eis | prugh |

| 2 | dios | deidher | 3 | trys | trigh |

| 4 | tethar | tethargh | 5 | pen | pengh |

| 6 | es | eth | 7 | eft | eidogh |

| 8 | oth | ovogh | 9 | enag | enagh |

| 10 | deg | degagh | 11 | enneg | ennegagh |

| 12 | dydeg | dydegagh | 13 | trydeg | trydegagh |

| 14 | tethardeg | tethardegagh | 15 | penneg | pennegagh |

| 16 | edheg | edhegagh | 17 | efteg | eftegagh |

| 18 | othudeg | othudegagh | 19 | enadeg | enadegagh |

| 20 | ivain | ivaid | 21 | ivain sin eis | ivaid sin prugh |

| 22 | ivain sin dios | ivaid sin deidher | 30 | ivain-deg | ivaindegagh |

| 31 | ivain-deg sin eis | ivaindegagh sin prugh | 40 | dioivain | dioivaid |

| 50 | dioivain-deg | dioivaindegagh | 60 | trivain | trivaid |

| 70 | trivain-deg | trivaindegagh | 80 | tetharvain | tetharvaid |

| 90 | tetharvain-deg | tetharvaindegagh | 100 | egagh | egadhod |

From egagh on, the numbers can be masculine or feminine:

| Number | Cardinal | Ordinal | Number | Cardinal | Ordinal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | diagesioi/ai | diagesiod | 300 | trygesioi/ai | trygesiod |

| 400 | tethragesioi/ai | tethragesiod | 500 | pennagesioi/ai | pennagesiod |

| 600 | esagesioi/ai | esagesiod | 700 | eftagesioi/ai | eftagesiod |

| 800 | othagesioi/ai | othagesiod | 900 | enagesioi/ai | enagesiod |

| 1000 | hilioi/ai | hiliod | 2000 | diahilioi/ai | diahiliod |

| 3000 | tryhilioi/ai | tryhiliod | 4000 | tethrahilioi/ai | tethrahiliod |

| 5000 | pennahilioi/ai | pennahiliod | 6000 | esahilioi/ai | esahiliod |

| 7000 | eftahilioi/ai | eftahiliod | 8000 | othahilioi/ai | othahiliod |

| 10000 | mirioi/ai | miriod | 11000 | mirioi/ai sin hilioi/ai | miriod sin hiliod |

| 20000 | dimirioi/ai | dimiriod | 100000 | egagh-hilioi | egagh-hiliod |

| 500000 | pennagesioi-hilioi | pennagesioi-hiliod | 1000000 | kryn | krynod |

| 2000000 | dios krynoi | deidher krynod | 1000000000 | riagryn | riagryd |

Pronouns and kinds of adjectives

Personal pronouns

Brythohellenic personal pronouns have three cases: nominative, accusative, and dative. In Brythohellenic there is no need to indicate subject pronoun before the verb, whereas in English it is compulsory.

| Case | 1st person | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |||

| Nominative | eu | nüi | ||

| Accusative | me | nüi | ||

| Dative | moi | nüin | ||

| Case | 2nd person | |||

| Singular | Plural | |||

| Nominative | hi | üi | ||

| Accusative | he | üi | ||

| Dative | hoi | üin | ||

| Case | 3rd person | |||

| Masculine s. | Feminine s. | Masculine pl. | Feminine pl. | |

| Nominative | o | ý | oi | ai |

| Accusative | ton | tyn | tus | tas |

| Dative | tu | ty | tois | tais |

In a sentence the pronouns in dative case are positioned before of those in accusative case, so prepositions can be omitted, ex.:

- Dure moi tyn - Give it to me.

The neuter pronoun it is translated in Brythohellenic with ý. The feminine pronoun ý is written with the accent to be distinguished from the preposition y (= "than"). When there are a pronoun and a noun, the pronoun always precedes the noun, ex.:

- Dure tyn brys to coiren - Give it to the lady;

- Dure ty to cïun - Give her the dog.

Demonstratives

There are two demonstratives: yun (= "this") and legh (= "that"). The first demonstrative matches perfectly the first person, whereas the second one matches both the second and the third person:

| Person | Adverb | Demonstrative | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | naugh (= here) | yun | this |

| 2nd | cys (= there) | legh | that |

| 3rd |

Demonstratives don't inflect and always follow the nouns they are referred to, and the nouns take also the article, ex.:

- To ailur yun - This cat.

- Ru eu en oic to yun - I'm in this house;

- Bainu eu e hoicoi to legh - I come from those houses.

Possessives

Possessives can be used both as pronouns and adjectives. When they are used as adjectives, they always follow the noun they refer to.

| Possessives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural |

| eu | evon | evas |

| hi | hon | has |

| o | dhu | |

| ý | dhys | |

| nüi | yveron | yveras |

| üi | iveron | iveras |

| oi / ai | dhun | |

Here are some examples:

- Ailur evon - My cat;

- Cïun hon - Your dog;

- Ginys dhu - His wife;

- Enyr dhys - Her man;

- Thyr yveron - Our animal;

- Fil iveron - Your friend;

- Calen dhun - Their heart.

Plural:

- Ailuroi evas - My cats;

- Cinoi has - Your dogs;

- Ginai dhu - His wives;

- Anras dhys - Her men;

- Thyras yveras - Our animals;

- Filoi iveras - Your friends;

- Calenai dhun - Their hearts.

Possessives don't allow the use of the article. Third person possessives don't inflect.

Relatives and 'interro-exclamatories'

Interrogative pronouns, which are used also to make exclamations, function also as relatives:

| Case | Tis (who) | Ti (what) |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | tis | ti |

| Accusative | ten | ti |

| Dative | ty | ty |

| Genitive | tun | tun |

Ex.:

- Tis it o? - Who is he?

- Tis cïun calin! - What a beautiful dog!

- Tun it to bivel yun? - Whose is this book?

- Ty ellas tyn? - Whom have you said it to?

- To legh it to ginys ten filu - That is the woman whom I love.

Indefinites

Indefinites give us incomplete information, because they don't define the precise quantity or the identity:

| Indefinite | Meaning |

|---|---|

| udhis | someone/anyone |

| edhi | something/anything |

| mydys | nobody |

| myden | nothing |

| olen | each |

| pan | all |

| edher | other |

| ovodh | same, self |

When pan is used as adjective, it has the singular form pas and the plural forms panas for masculine and pasai for feminine. Also edher has the plural: edheroi for masculine and edherai for feminine.

Indefinites can be formed also with the word alen:

- To alenoi/ai - The others;

- Crysys edhi alen? - Do you need something else?

- Gnocy ý udhis alen? - Does she know someone else?

Adverbs

Usually adverbs are formed by suffixation: many adverbs derive from adjectives, to that the suffix -eus is added. Some examples:

- elev > elveus (happy - happily);

- lir > lireus (sad - sadly);

- meal > mealeus (great - greatly);

- thenar > thenareus (strong - strongly);

- athin > athineus (weak - weakly).

Some adverbs have suppletive forms, ex.: ivygh > ei; penyr > faul.

Adverbs occupy a precise position within the sentence:

- 1) adverbs always follow subject, ex.: ru eu mal elev (= "I am very happy"), dagruy ý thenareus (= "She cries strongly");

- 2) adverbs always precede adjectives, ex.: ryu o elion lir (= "He's a little sad").

Place adverbs

In Brythohellenic place adverbs naugh and cys inflect to express state or movement to and from. The adverb u, "where", also inflects:

| Form | U | Naugh | Cys |

|---|---|---|---|

| State | u | naugh | cys |

| Movement to | oi | naudhes | cyses |

| Movement from | üen | naudhen | cysen |

The adverb u also has a relative function:

- It to yun to peli, üen bainu - This is the town where I come from;

- It to ledh to peli, oi ovylu ergyn - That is the town where I have to go.

Other place adverbs are: alogh, alodhes, alodhen, respectively "elsewhere", "from elsewhere", "(to) elsewhere"; udhovu, "nowhere" and "from nowhere", udhovon, "(to) nowhere"; edhovu "somewhere" and "from somewhere", edhovon, "(to) somewhere".

Time adverbs

The adverb yneg, "when", can be used both as interrogative and relative. Other time adverbs are:

- nin - now;

- enna - then;

- prothen - before;

- ivyn - after;

- dyvogh - some times;

- hinydhen - usually;

- ey - always;

- oseg - ever;

- uvogh - never;

- alogh - another time.

Verbs

The verbal system has undergone deep alterations that have strongly simplified it. Neohellenic has only 4 moods: indicative, imperative, infinitive, and participle; the other Ancient Greek moods have been completely lost. This rather evident simplification has modified also the tenses. The modern language has only 4 tenses: present, imperfect, perfect (that originates from the ancient aorist, actually), and future. This is true for the indicative mood only, the others have only two or even one tense. Moreover the language has lost the dual forms, retaining only 6 verbal persons.

To be

The verb to be is, as in the majority of languages, irregular, but, what distinguishes Brytho-Hellenic is that it has two different forms of this verb, even if the infinitive form is the same:

- the verb ru eu (= I am) is used to describe something or someone, to express a position, to indicate a temporary state, ex.: Ru eu elev (= I am happy), Rys hi en oic to yun (= You are in this house), Ryu ý eivan (= She's angry);

- the verb yv eu (= I am) is used to say what something is, to indicate identity, to express a permanent state, and to emphasise something, ex.: Yv eu enyr (= I am a man), Y hi adelu evon (= You are my brother), It ý ivygh (= She's (a) good (person)); Eté üi, ten filu eu (= You are the ones whom I love).

Not all the verbal persons have different forms, the third person plural has only one form as it can be seen in the following table:

| Byn | ||

|---|---|---|

| Person | "ru eu" | "yv eu" |

| eu | ru | yv |

| hi | rys | y |

| o / ý | ryu | it |

| nüi | ren | emén |

| üi | rych | eté |

| oi / ai | ys | |

Present tense

Generally the present tense is used to talk about habitual actions that happen regularly, just as in English: Every Friday I play football with friends. This tense is also used to talk about facts that are considered true, ex.: Water boils at 100°C, and also to talk about an action that is happening at the moment of speaking, whereas in English one would rather use the progressive form, which, actually, does exist also in Neohellenic, even if it is rarely used. In Brytho-Hellenic many important verbs are irregular and they have peculiarities that must be learned and cannot be summed up in tables. Most verbs though are regular and, of course, all the new coinages are regular. As many verbs have a regular present, but an irregular imperfect or perfect, it is better to talk of regular present rather than "present of regular verbs". The regular present can follow two different patterns, known as e-pattern and u-pattern: these names come from the vowel of the ending of the 1st person plural. The persons of the singular and the 3rd person plural have always the same endings, only the first two persons of the plural can change and by knowing which pattern the verb belongs to, one can predict the ending of the 1st and the 2nd persons plural. Let's see the present tense of these six verbs: feryn, "to bring", egyn, "to have", lanyn, "to take", syn, "to live", lalyn, "to speak", and filyn, "to love".

| Regular verbs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | e-pattern | u-pattern | ||||

| Feryn | Egyn | Lanyn | Syn | Lalyn | Filyn | |

| eu | feru | egu | lanu | su | lalu | filu |

| hi | ferys | egys | lanys | sys | lalys | filys |

| o / ý | fery | egy | lany | sy | laly | fily |

| nüi | feren | egen | lanen | sun | lalun | filun |

| üi | ferech | egech | lanech | sych | lalych | filych |

| oi / ai | ferus | egus | lanus | sus | lalus | filus |

Present of "i-verbs"

There are some verbs, not too many, actually, that insert a tonic i between the root and the endings in the present and in the imperfect: because of this they are called i-verbs. Two important verbs of this kind are ethyn, "to eat", and lyn, "to free, to release":

| I-verbs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Person | Ethyn | Lyn |

| eu | ethïu | lïu |

| hi | ethys | lys |

| o / ý | ethy | ly |

| nüi | ethïen | lïen |

| üi | ethïech | lïech |

| oi / ai | ethïus | lïus |

All i-verbs are e-pattern verbs.

Present of "contracted verbs"

Many verbs have an irregular present: unfortunately it isn't possible to establish some patterns, because the difference can lie in the whichever person when not in all of them. Very often the different endings are the result of vowel contractions that took place in antiquity, thus these verbs are called contracted verbs. Here it is the present tense of the verbs leyn, "to say, to tell", düyn, "to give", poin, "to do, to make", acüyn, "to listen", and oran, "to see":

| Contracted verbs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Leyn | Düyn | Poin | Acüyn | Oran |

| eu | leu | du | pou | acú | oru |

| hi | leys | düys | pois | acüys | oras |

| o / ý | ley | düy | poi | acüy | ora |

| nüi | leuen | dun | poun | acüen | orüen |

| üi | lech | duch | poich | acüech | orach |

| oi / ai | leus | dus | pous | acús | orus |

"A-verbs"

The verb oran belongs to a special class of contracted verbs: the a-verbs. These verbs show an a in some endings and, above all, in the infinitive instead of the classic y. These are the only irregular verbs with a predictable pattern, as we can see with other examples, such as the verbs dogan, "to wait", tivan, "to honour", and gelan, "to laugh":

| A-verbs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Dogan | Tivan | Gelan |

| eu | dogu | tivu | gelu |

| hi | dogas | tivas | gelas |

| o / ý | doga | tiva | gela |

| nüi | dogüen | tivüen | gelüen |

| üi | dogach | tivach | gelach |

| oi / ai | dogus | tivus | gelus |

The progressive form

Neohellenic has developed a progressive form of the present and the formation of it let linguists think that it derives from Celtic languages. Nowadays the progressive form is less and less used, except for some Occidental dialects which even prefer this form to the simple present. The present progressive is formed with verb byn (ru eu) + en + infinitive of the verb, ex.:

- Ru eu en paisyn hin to civicoi. > I'm playing dice.

- Ys oi en oran to paid. > They are seeing the child.

Imperfect tense

The imperfect is used to talk about habitual actions that happened in the past. English lacks a counterpart for this tense: the same meaning could be obtained using the Simple past or, even better, the pattern "used to + infinitive": I used to play football with friends every Friday. This tense is also used to talk about actions that were happening in the past, to underline their duration, whereas in English one would rather use the Past Progressive, which, anyway, exists also in Neohellenic, but, as for the progressive form of the present, it is rarely used. As it has been said, in Brythohellenic many verbs have a regular present, but an irregular imperfect, so it is impossible to talk about "regular verbs". However there are some "structural changes" in the formation of this tense that are common and can be analysed. Let's see the imperfect of six verbs whose present tense has already been observed and of the verb "to be", that has two different forms for this tense too.

| Person | e-pattern | u-pattern | Byn | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feryn | Egyn | Lanyn | Syn | Lalyn | Filyn | ru eu | yv eu | |

| eu | efron | ygon | elanon | esun | elalun | efilun | erun | yn |

| hi | efres | yges | elanes | esys | elalys | efilys | erys | ytha |

| o / ý | efre | yge | elane | esy | elaly | efily | ery | yn |

| nüi | eferen | ygen | elanen | esun | elalun | efilun | erun | yven |

| üi | eferech | ygech | elanech | esych | elalych | efilych | erych | ych |

| oi / ai | efron | ygon | elanon | esun | elalun | efilun | erun | ysan |

The imperfect is formed by adding a "tense marker" that is known as "imperfect marker" or "augment" and is represented by an e- which is added to the verb root as it appears in the present tense. If the root already begins with this vowel, it is substituted for y-. SOme verbs underwent some changes like syncopes or consonantal modifications. The e-pattern verbs have the following endings: -on, -es, -e, -en, -ech, -on; whereas the u-pattern verbs have the endings: -un, -ys, -y, -un, -ych, -un, which correspond in all persons - except for the 1st singular and the 3rd plural - to the present forms.

Imperfect of "i-verbs"

The so called "i-verbs" essentially behave as all the other e-pattern verbs, but their characteristical i is inserted between the root and the endings. In the present tense this vowel, where it occurs, is always tonic, in the imperfect this vowel occurs in all persons, but it is accented only in the 1st and the 2nd persons of plural, whereas in the other persons it forms a diphthong with the endings' vowels.

| I-verbs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Person | Ethyn | Lyn |

| eu | ythion | elion |

| hi | ythies | elies |

| o / ý | ythie | elie |

| nüi | ythïen | elïen |

| üi | ythïech | elïech |

| oi / ai | ythion | elion |

Imperfect of "contracted verbs"

Contracted verbs have generally a rather regular imperfect, in the sense that they have the augment and the typical imperfect endings:

| Contracted verbs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Leyn | Düyn | Poin | Acüyn |

| eu | elon | edun | epoun | ycuon |

| hi | eles | eduys | epois | ycues |

| o / ý | ele | eduy | epoi | ycue |

| nüi | eleuen | edun | epoun | ycüen |

| üi | elech | educh | epoich | ycüech |

| oi / ai | elon | edun | epoun | ycuon |

Note that the verb acüyn substitutes its beginning a- for y-.

Imperfect of "a-verbs"

Let's see the imperfect form of the so called "a-verbs":

| A-verbs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Oran | Dogan | Tivan | Gelan |

| eu | eurun | edogun | etivun | eglun |

| hi | euras | edogas | etivas | eglas |

| o / ý | eura | edoga | etiva | egla |

| nüi | eurun | edogun | etivun | egelun |

| üi | eurach | edogach | etivach | egelach |

| oi / ai | eurun | edogun | etivun | eglun |

Note the modification in the root of the verb oran, which changes its o with a u that forms a diphthong with the tense marker, and the syncope of the verb gelan in the persons of singular and in the 3rd person plural.

Vocabulary

Colour terms

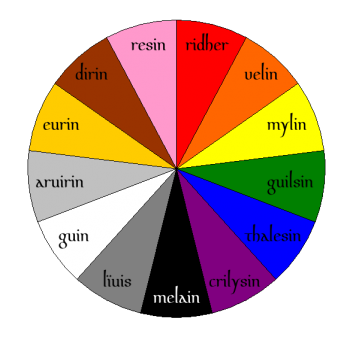

The colour system of Brytho-Hellenic is curious, because except white, black and red, colour names derive from flowers or natural elements. Historians have supposed that as the Greeks of Conon reached Great Britain they used natural elements to establish a first contact between their languagage and the language of Celtic people. There are also other colour terms that come from Ancient Greek, such as clur (= "green"), porhir (= "purple-red"), aruirin (= "silver") or hegin (= "bronze-coloured"), but they are old-fashioned nowadays and they are used almost exclusively in literature.

| Colour terms | ||

|---|---|---|

| Compare with | Brythohellenic | English |

| μέλαινα (Ancient Greek) | melain | black |

| κελαινός (Ancient Greek); furvus (Latin) | celain; furg | dark, obscure |

| λαμπρός (Ancient Greek) | lemyr | light, pale, fair |

| lividus (Latin), llwyd (Welsh), disliw (Cornish) | lïuis | grey |

| gwyn (Welsh), gwynn (Cornish) | guin | white |

| φαλακρός (Ancient Greek) x eglur (Welsh) | faiglur | bright, lucid |

| rudhvelyn (Cornish), "orange" | velin | orange |

| ἐρυθρός (Ancient Greek), rhudd (Welsh), rudh (Cornish) | ridher | red |

| πορφυροῦς (Ancient Greek) | porhir | purple-red |

| gwaed (Welsh), "blood" | guaidin | burgundy |

| crinllys (Welsh), "violet (flower)" | crilysin | violet, purple |

| ινδικόν (Ancient Greek), "that comes from India" | innic | indigo |

| χλωρός (Ancient Greek); gwels (Cornish), "grass" | clur; guilsin | green |

| ebron (Cornish), "sky" | brenin | light blue, cyan |

| θάλασσα (Ancient Greek), "sea" | thalesin | dark blue |

| mêl (Welsh), mel (Cornish), "honey" | mylin | yellow |

| dur (Cornish), "earth" | dirin | brown |

| χρυσός (Ancient Greek), "gold"; owr (Cornish), "gold"; | crisin; eurin | golden |

| rosen (Cornish), "rose" | resin | pink |

| ἄργυρος (Ancient Greek), "star"; steren (Cornish), "star" | aruirin; ytrin | silver |

| χαλκός (Ancient Greek), "bronze"; efydd (Welsh), "bronze" | helgin; yvydhin | bronze-coloured |

Fruit and vegetables

| Fruit and vegetables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Compare with | Brythohellenic | English |

| μῆλον (Ancient Greek), "apple" | myl | red apple |

| afal (Welsh), aval (Cornish), "apple" | aval | yellow apple, generic apple |

| κυδωνία (Ancient Greek), "quince" | cidun | green apple |

| στάλαγμα (Ancient Greek), "drop" | talamagh | grape |

| citreum (Latin), "lemon" | cidhyr | lemon |

| χρυσοῦν μῆλον (Ancient Greek), "golden apple" | crimyl | orange |

| هلو (Persian), "peach" | heulv | peach |

| ἐλαία (Ancient Greek), "olive" | elagh | olive |

| لیموترش (Persian), "lemon" | lameutyr | lime |

| κέρασος (Ancient Greek), "cherry" | ceres | cherry |

| ruber (Latin), "bright red" | ryuir | watermelon |

| αγγούριον (Ancient Greek), "cucumber" | onuir (pl. onuir-) | cucumber |

| انجیر (Persian), "fig" | neiar | fig |

| ananas (Tupian or Guaraní) > ananassum (Neolatin), "pineapple" | nanas | pineapple |

| sevien (Cornish), syfien (Welsh), "strawberry" | syvyn | strawberry |

| νύξ (Ancient Greek), "night" + mwyaren (Welsh), "berry" | nithuirn | blueberry |

| du (Welsh), du (Cornish), "black" + mwyaren (Welsh), "berry" | dyuirn | blackberry |

| tomatl (Nauhatl) > tomatĭlum (Neolatin), "tomato" | tovygh | tomato |

| mahiz (Arawakan) > mahīsum (Neolatin), "maize" | mehys | maize |

| موز (Persian), "banana" | meus | banana |

| زردآلو (Persian), "apricot" | serdel | apricot |

| προυνον (Ancient Greek), "plum" | brun | plum |

| قهوة (Arabic) > قهوه (Perisan), "coffee" | heuif | coffee |

| 茶 (Chinese) > چای (Persian), "tea" | sea (pl. seai) | tea |

| xocolatl (Nahuatl) > chocolatĭlum (Neolatin), "chocolate" | cegolygh | cacao (beans) |

| باذنجان (Arabic) > بادنجان (Persian), "eggplant" | badynyn | eggplant |

| cucurbĭta (Latin), "courgette" | cirvegh | courgette |