Natalician: Difference between revisions

(→Voice) Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

|ancestor = Old Natalician | |ancestor = Old Natalician | ||

}} | }} | ||

'''Natalician''' ({{IPA|/nəˈtɑlɪʃən | '''Natalician''' ({{IPA|/nəˈtɑlɪʃən/}}; [[w:Endonym|endonym]]: ''Nataledhi'' {{IPA|[na.ta.le.di]}} or ''Natal Rettive'' {{IPA|/na.tal re.tːive/}}) is a North Kasenian language predominantly spoken in Central East Tinaria, specifically in Natalicia, Firenia, and North-East Nirania. Beyond Natalicia, it holds official status in Budernie, Nirania, and Kannamie, and is recognized as a minority language in East Espidon and within the Dogostanian community in Eastern Amarania. Natalician shares a close linguistic relationship with other North Kasenian languages, such as Espidan and Niranian. | ||

Modern Natalician evolved from Old Natalician, which itself descended from an extinct, unnamed language spoken by the Natalo-Kesperian tribes. Today, Natalician stands as one of the world's most significant languages, boasting the highest number of speakers among the Kasenian languages, both as a native and a second language. Approximately 65 million people worldwide speak Natalician, including 37 million native speakers. | Modern Natalician evolved from Old Natalician, which itself descended from an extinct, unnamed language spoken by the Natalo-Kesperian tribes. Today, Natalician stands as one of the world's most significant languages, boasting the highest number of speakers among the Kasenian languages, both as a native and a second language. Approximately 65 million people worldwide speak Natalician, including 37 million native speakers. | ||

Revision as of 20:45, 19 July 2024

This article is private. The author requests that you do not make changes to this project without approval. By all means, please help fix spelling, grammar and organisation problems, thank you. |

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

| Natalician | |

|---|---|

| Nataledhi | |

Flag of the Natalician Republic | |

| Pronunciation | [na.ta.le.di] |

| Created by | Hazer |

| Date | 2021 |

| Setting | Hazerworld |

| Native to | Natalicia; Firenia and the Kontamchian Islands |

| Ethnicity | Natales |

| Native speakers | 37,123,487 (2021) |

Tinarian

| |

Early form | Old Natalician

|

Standard form | Standard Central Natalician (Kieneh Rasah Nataledhi)

|

Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | Natalicia |

Recognised minority language in | Espidon, Amarania (Dogostania) |

| Regulated by | The Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics |

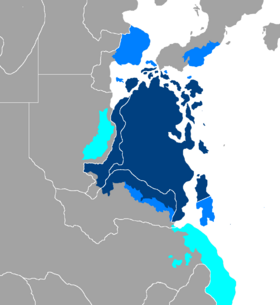

A map showing the distribution of (native and non-native) speakers of Natalician in Tinaria. Dark blue is native, light blue is secondary language speaker, and cyan is minorities. | |

Natalician (/nəˈtɑlɪʃən/; endonym: Nataledhi [na.ta.le.di] or Natal Rettive /na.tal re.tːive/) is a North Kasenian language predominantly spoken in Central East Tinaria, specifically in Natalicia, Firenia, and North-East Nirania. Beyond Natalicia, it holds official status in Budernie, Nirania, and Kannamie, and is recognized as a minority language in East Espidon and within the Dogostanian community in Eastern Amarania. Natalician shares a close linguistic relationship with other North Kasenian languages, such as Espidan and Niranian.

Modern Natalician evolved from Old Natalician, which itself descended from an extinct, unnamed language spoken by the Natalo-Kesperian tribes. Today, Natalician stands as one of the world's most significant languages, boasting the highest number of speakers among the Kasenian languages, both as a native and a second language. Approximately 65 million people worldwide speak Natalician, including 37 million native speakers.

Natalician is characterised by its lack of grammatical cases, absence of grammatical genders, minimal irregularity, and a systematic grammar. Its orthography is straightforward, devoid of digraphs, diphthongs, or similar complexities, making it an accessible language to read and learn.

History

The earliest traces of the Natalician language date back to the year 334, featuring a vocabulary and grammar markedly different from its modern descendant. The history of the Natalician language is divided into three distinct periods: Classic Natalician (334–1203), Old Natalician (1203–1540), and Modern Natalician (1540–present). As of 2021, the language is estimated to be 1,687 years old.

Classic Natalician

Also known as Poetic Natalician or the Natalo-Kesperian Language, the earliest traces of this language are found solely in ancient poetry and inscriptions on recovered artifacts. However, the NACL (Natalician Academy of Classical Languages) considers these remnants insufficient to be deemed a complete or valid representation of the spoken Natalo-Kesperian language, largely due to the dominance of illiteracy in the pre-Killistic era and the overly formal nature of the vocabulary used in these writings.

Classic Natalician's vocabulary contains numerous direct elements from the early Proto-North-Kasenian language, which eventually faded during the migratory era. This decline was influenced by cultural clashes and the increasing incorporation of loanwords.

Unfortunately, no documents from the Classic Natalician period have survived. Consequently, there is no known evidence detailing the development of the language during this primary era.

Old Natalician

Reširi ägsös nör på tånåka if kelševi wez̊en fölsi sos.

“The people have the right to write and say what they please.”

With the dawn of the Killistic era, the Natale tribes gained access to invaluable knowledge, brought by the ascension of their proclaimed king, Ribel Zömeri. This period marked a significant rise in literacy rates within the nascent and unified Natale monarchy, which spanned from 1203 to 1834. During this era, the Natalician language saw its first instances of written records and experienced a flourishing of printed works.

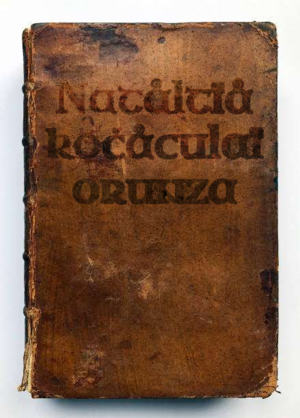

The earliest known book containing written evidence of the Natalician language is titled "Natåltïå kočåculaï orūnza" (Natalician Guide Book). This seminal work was authored and published by the late Ulun Cilesli Irkete in the year 1210. Subsequently, numerous documents have been preserved through generations and are now treasured artifacts housed in the Natalician Grand Museum of Literature and Artifacts in Celicia.

Many historians and literary scholars have debated the relationship between Classic and Old Natalician, with some arguing that they are identical. However, the scarcity of evidence has left these claims unresolved. Scholar Iček Friktinäm posits: "Old Natalician may be the result of the incorporation of new local loanwords, and the diverse dialects might have led to deviations from the Kasenian roots of the standard spoken Natalician of that time."

Old Natalician is characterized by significantly different grammar and vocabulary compared to modern Natalician. The most notable differences include the presence of vowel harmony and grammatical cases. The language featured four types of vowel harmony and three grammatical cases: Nominative, Accusative, and Genitive. Additionally, distinct suffixes and verb conjugations highlight the major grammatical differences.

Modern Natalician

Äg čan vizih zifekev if savekilivev ensei ťenałr nameš čan özev.

“Our history is filled with rich stories and leaders.”

The Natalician language has been continuously evolving since the 15th century with the decline of the monarchy and the rise of Goz Hoz. This evolution continued until the establishment of the Republic in 1845 by Zafel Sörät Fortla, when the "Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics" was created and assumed responsibility for tracking the language's development.

Etymology

The name Natalicia, the Natalese and the Natalician language, originates from the Natala tribes of the Natalo-Kesperian community in central east Tinaria. The term derives from the Proto-Kasenian word Nåťåla, meaning "to ensure fairness." This evolved into Nåsåla in Old Natalician and eventually became Nasala in Modern Natalician.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | |||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s θ | ʃ | h | ||||

| voiced | v | z ð | ʒ | ʁ | |||||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡ʃ | |||||||

| voiceless | d͡ʒ | ||||||||

| Approximant | semivowel | j | w | ||||||

| lateral | l | ||||||||

| Gorgia Toscana | |||||||||

| Flap | |||||||||

| Trill | |||||||||

Consonant Harmony

Natalician orthography reflects voice sandhi voicing, a form of consonant mutation with two consonants that meet, and the second is voiced and the first is unvoiced. The first unvoiced consonant [p t f ʃ t͡ʃ θ k s] is voiced to [b d v ʒ d͡ʒ ð ɡ z], but the orthography remains unchanged. This usually does not include load words.

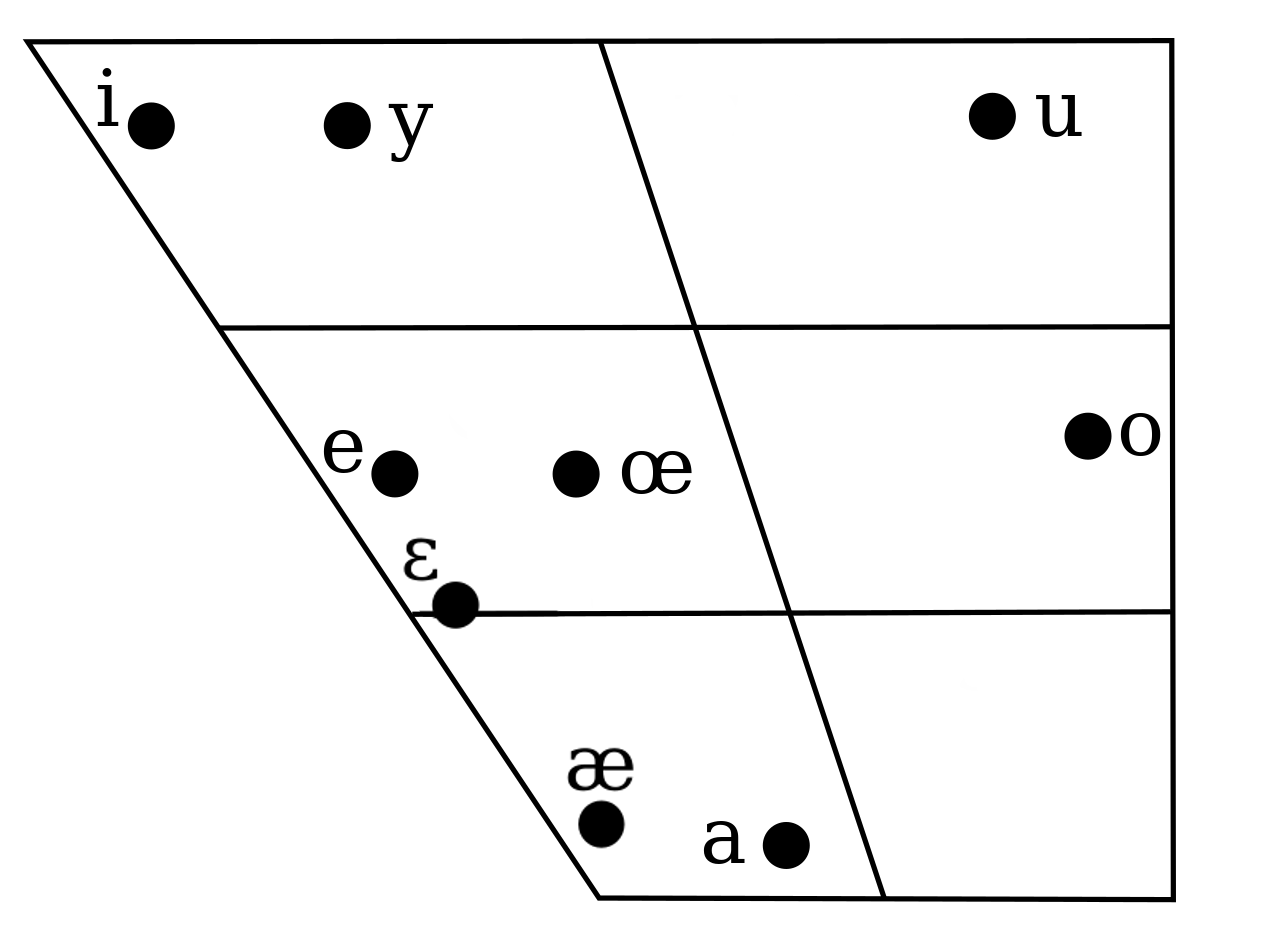

Vowels

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |

| Close | i | y | u | |

| Near-open | æ | |||

| Open | e | œ | a | o |

The vowels of the Natalician language are, in their alphabetical order, ⟨a⟩, ⟨ä⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨ü⟩.

The Natalician vowel system can be considered as being three-dimensional, where vowels are characterised by how and where they are articulated focusing on three key features: front and back, rounded and unrounded and vowel height.

Note

When the vowels /i/, /u/ precede or succeed another vowel, they become /j/, /w/ respectively. If both vowels meet one another, only the /i/ will transform into a /j/ which the /u/ remains unchanged.

Vowel harmony

| Natalician Vowel Harmony | Front Vowels | Back Vowels | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |||||||

| Vowel | ä | e | i | ö | ü | a | o | u | ||

| Type Ĭ (Backness + Rounding) | i | ü | a | u | ||||||

| Type Ĕ (Backness) | e | o | ||||||||

The principle of vowel harmony

- If the first vowel of a word is a back vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a back vowel; if the first is a front vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a front vowel.

- If the first vowel is unrounded, so too are subsequent vowels.

The second and third rules minimize muscular effort during speech. More specifically, they are related to the phenomenon of labial assimilation: If the lips are rounded (a process that requires muscular effort) for the first vowel they may stay rounded for subsequent vowels. If they are unrounded for the first vowel, the speaker does not make the additional muscular effort to round them subsequently.

Grammatical affixes have "a chameleon-like quality" and obey one of the following patterns of vowel harmony:

- Twofold (-e/-o): The article, for example, is -(v)e after front vowels and -(v)o after back vowels.

- Fourfold (-i/-a/-ü/-u): The verb infinitive suffix, for example, is -i or -a after unrounded vowels (front or back respectively); and -ü or -u after the corresponding rounded vowels.

- Type & 'and': The adjectival passive voice suffix, for example, is -t&t, the & being the same vowel as the previous one.

Practically, the twofold pattern (usually referred to as the type Ĕ) means that in the environment where the vowel in the word stem is formed in the front of the mouth, the suffix will take the e form, while if it is formed in the back it will take the o form. The fourfold pattern (also called the type Ĭ) accounts for rounding as well as for front/back. The type & pattern is the reppetition of the same last vowel. The following examples, based on the nominal suffix -zĭk, illustrate the principles of type Ĭ vowel harmony in practice: Čikelzik ("Wellness"), Okzuk ("Knowledge"), Ianzak ("Food"), Nörzük ("Living").

Exceptions to vowel harmony

These are four word-classes that are exceptions to the rules of vowel harmony:

- Native, non-compound words, e.g. Ela "then", Čela "drink", Äga "by"

- Native compound words, e.g. Pave "for what"

- Foreign words, e.g. many English loanwords such as Sertifikäht (certificate), Hospital (hospital), Komphuter (computer)

- Invariable prefixes / suffixes:

| Invariable prefix or suffix | Natalician example | Meaning in English | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| –(v)iš | üčiš | "exit" | From üč "leave." |

| öz- | özhaša | "to return" | From haša "to come" |

| gik- | gikögültüt | "unwanted" | From ögültüt "wanted" |

Note

- A native compound does not obey vowel harmony: Ras+cezil ("city center"—a place name)

- Loanwords also disobeys vowel harmony: Kofi ("Coffee")

- Every grammatical prefix disobeys the vowel harmony aswell.

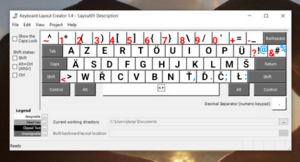

Orthography

Alphabet

Natalician has a straightforward orthography, meaning regular spelling with (almost) no diphthong or digraph or anything of the sort. In linguistic terms, the writing system is a phonemic orthography. The following are exceptions:

- The letter that is called Girbit El ("Silent L"), written ⟨Ł⟩ in Natalician orthography, represents vowel lengthening. It never occurs at the beginning of a word or a syllable, always follows a vowel and always preceeds a consonant. The vowel that preceeds it is lengthened.

- The letter ⟨H⟩ in Natalician orthography represents two sounds: The /h/ sound, and the /j/ sound. If the letter ⟨H⟩ is located at the beginning of the word, it takes the /h/ sound, otherwise it takes the /j/ sound. (e.g. Hiloh /hi.loj/ "Hello", Konah /ko.naj/ "Beautiful", Haz /haz/ "This")

Standard Natalician alphabet

| Letter | Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Aa | a [a] | /a/ |

| Ää | ä [æ] | /æ/ |

| Bb | be [be] | /b/ |

| Cc | ce [d͡ʒe] | /d͡ʒ/ |

| Čč, | če [t͡ʃe] | /t͡ʃ/ |

| Dd | de [de] | /d/ |

| Ďď | ďe [ðe] | /ð/ |

| Ee | e [e] | /ɛ/, /e/ |

| Ff | ef [ɛf] | /f/ |

| Gg | ge [ɡ] | /g/ |

| Hh | ha [ha] | /h/, /j/ |

| Ii | i [i] | /i/, /j/ |

| Jj | je [ʒe] | /ʒ/ |

| Kk | ka [ka] | /k/ |

| Ll | el [ɛl] | /l/ |

| Łł | girbit el [gir.bit ɛl] | /ː/ |

| Mm | em [ɛm] | /m/ |

| Nn | en [ɛn] | /n/ |

| Oo | o [o] | /o/ |

| Öö | ö [œ] | /œ/ |

| Pp | pe [pe] | /p/ |

| Rr | er [r] | /r/ |

| Řř | eř [ɛʁ] | /ʁ/ |

| Ss | es [s] | /s/ |

| Šš | eš [ɛʃ] | /ʃ/ |

| Tt | te [te] | /t/ |

| Ťť | ťe [θe] | /θ/ |

| Uu | u [u] | /u/ |

| Üü | ü [y] | /y/ |

| Vv | ve [ve] | /v/ |

| Ww | wa [wa] | /w/ |

| Zz | ze [ze] | /z/ |

Grammar

Natalician grammar can be compared to that of the English language to an extent. Cases were dropped during the middle stages of the language, and like the rest of the Tinarian languages, there is no gendered nouns.

Pronouns

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| Personal Pronoun | Nei | On | Sü | Namše | Daš | So |

| Object Pronoun / Possessive Determiner | (V)In | (V)U | Süs | Nameš | Daša | Soz |

| Possessive Pronoun | (V)Ini | (V)Onu | Süzü | Nameše | Dašo | Sozun |

The pronouns (V)In, (V)U, (V)Ini and (V)Onu will use the V if the preceding noun ends with a vowel. In a sentence, the possessive determiner will always succeed the object. The object pronoun usually comes after the verb:

- Haz ensei ianzak in - This is my food

- Iandaita ťimana vin - You ate my grape

- Rimtiz soz kołru - I saw them yesterday

Verbs

Stems of verbs

Many stems in the dictionary are indivisible; others consist of endings attached to a root.

Verb-stems from nouns

The verb-stem Maršo- "Build" is the adjective Mar "A build" with the suffix -šo. Many verbs are formed from nouns or adjectives with -šĕ:

Noun Verb Ergem "negativity" Ergemše- "negate" To "two" Tošo- "Two-ify", that is, "get married" Kel "word" kelše- "say"

Voice

A verbal root, or a verb-stem in -šĕ, can be lengthened with certain extensions. If present, they appear in the following order, and they indicate distinctions of voice:

Extensions for voice Voice Ending Example Reflexive -(ĭ)r; Kark (wash); Karkar (shower) Reciprocal -cĕ; Dol (send); Dolco (exchange) Causative -(&)z; Ian (eat); Ianaz (feed) Passive -(ĭ)v; Artan (help); Artanav (be helped)

These endings might seem to be inflectional in the sense of the Template:Section link above, but their meanings are not always clear from their particular names, and dictionaries do generally give the resulting forms, so in this sense they are constructive endings.

The causative extension makes an intransitive verb transitive, and a transitive verb factitive. Together, the reciprocal and causative extension make the repetitive extension -(i)ştir.

Verb Root/Stem New Verb Voice Dol "Send" Dolco "Exchange" -ur (reciprocal) Doluv "Be sent" -uv (reflexive) Ver "Fix (something)" Veriv "wash oneself" -iv (reflexive) yıkanıl "be washed" -n (reflexive) + -ıl (passive) kayna "(come to a) boil" kaynat "(bring to a) boil" -t (causitive) öl "die" öldür "kill" -dür (causitive) - öldür "kill"

öldürt "have (someone) killed" -t (causitive, factitive) ara "look for" araştır "investigate" -ş (reciprocal) + -tır (causitive) = (repetitive)

Negation and potential in verb-stems

A dictionary-stem is positive; it can be made:

- negative, by addition of -me;

- impotential, by addition of -e and then -me.

Any of these three (kinds of) stems can be made potential by addition of -e and then -bil. The -bil is not enclitic, but represents the verb bil- "know, be able"; the first syllable of the impotential ending represents an obsolete verb u- "be powerful, able" Lewis [VIII,55]. So far then, there are six kinds of stems:

Paradigm for stems negative, impotential and potential English infinitive English finite form gel- "come" "come" gelme- "not come" "do not come" geleme- "be unable to come" "cannot come" gelebil- "be able to come" "can come" gelmeyebil- "be able to not come" "may not come" gelemeyebil- "able to be unable to come" "may be unable to come"

Such stems are not used for aorist forms, which have their own peculiar means of forming negatives and impotentials.

Note that -ebil is one of several verbs that can be compounded to enhance meaning. See Auxiliary verbs.

Bases of verbs

The characteristics with which verb-bases are formed from stems are given under Template:Section link. Note again that aorist verbs have their own peculiar negative and impotential forms.

The progressive base in -mekte is discussed under Template:Section link. Another base, namely the necessitative (gereklilik), is formed from a verbal noun. The characteristic is -meli, where -li forms adjectives from nouns, and -me forms gerunds from verb-stems. A native speaker may perceive the ending -meli as indivisible; the analysis here is from #Lewis [VIII,30]).

The present base is derived from the ancient verb yorı- "go, walk" #Lewis [VIII,16]; this can be used for ongoing actions, or for contemplated future actions.

The meaning of the aorist base is described under #Adjectives from verbs: participles.

There is some irregularity in first-person negative and impotential aorists. The full form of the base -mez (or (y)emez) reappears before the interrogative particle mi:

- Gelmem "I do not come" (cf. Gelmez miyim "Do I not come?");

- Gelmeyiz "We do not come" (cf. Gelmez miyiz "Do we not come?")

The definite past or di-past is used to assert that something did happen in the past. The inferential past or miş-past can be understood as asserting that a past participle is applicable now; hence it is used when the fact of a past event, as such, is not important; in particular, the inferential past is used when one did not actually witness the past event.

A newspaper will generally use the di-past, because it is authoritative. The need to indicate uncertainty and inference by means of the miş-past may help to explain the extensive use of ki in the newspaper excerpt at Turkish vocabulary#The conjunction ki.

The conditional (şart) verb could also be called "hypothetical"; it is used for remote possibilities, or things one might wish for. (See also #Compound bases.)

The various bases thus give distinctions of tense, aspect and mood. These can be briefly tabulated:

First-person singular verbs Form Suffix Verb English Translation Progressive -mekte gelmekteyim "I am in the process of coming" Necessitative -meli gelmeliyim "I must come" Positive -(i/e)r gelirim "I come" Negative -me(z) gelmem "I do not come" Impotential -(y)eme(z) gelemem "I cannot come" Future -(y)ecek geleceğim "I will come" Inferential Past -miş gelmişim "It seems that I came" Present/Imperfective -iyor geliyorum "I am coming" Perfective/Definite Past -di geldim "I came" Conditional -se gelsem "if only I came"

Questions

The interrogative particle mi precedes predicative (type-I) endings (except for the 3rd person plural -ler), but follows the complete verb formed from a verbal, type-II ending:

- Geliyor musunuz? "Are you coming?" (but: Geliyorlar mı? "Are they coming?")

- Geldiniz mi? "Did you come?"

Optative and imperative moods

Usually, in the optative (istek), only the first-person forms are used, and these supply the lack of a first-person imperative (emir). In common practice then, there is one series of endings to express something wished for:

Merged Optative & Imperative Moods Number Person Ending Example English Translation Singular 1st -(y)eyim Geleyim "Let me come" 2nd — Gel "Come (you, singular)" 3rd -sin Gelsin "Let [her/him/it] come" Plural 1st -(y)elim Gelelim "Let us come" 2nd -(y)in(iz) Gelin "Come (you, plural)" 3rd -sinler Gelsinler "Let them come"

Copula

The copula in Turkish appears in only two variants―*imek, a defective verb often attached to the noun, and olmek, which is a detached regular auxiliary verb.

*Imek, derived from the ancient verb er- #Lewis [VIII,2], survives in Turkish only in the inferential past, perfective, and conditional:

- imiş,

- idi,

- ise.

The form iken given under #Adverbs from verbs is also descended from er-. Since no more bases are founded on the stem i-, this verb can be called defective. In particular, i- forms no negative or impotential stems; negation is achieved with the #Adverb of negation, değil, given earlier.

The i- bases are often turned into base-forming suffixes without change in meaning; the corresponding suffixes are

- -(y)miş,

- -(y)di,

- -(y)se,

where the y is used only after vowels. For example, Hasta imiş and Hastaymış both mean, "Apparently/Reportedly, he/she/it is ill".

The verb i- serves as a copula. When a copula is needed, but the appropriate base in i- does not exist, then the corresponding base in ol- is used; when used otherwise this stem means "become". Idir, a variant of imek, is used for emphasis.

The verb i- is irregular in the way it is used in questions: the particle mi always precedes it:

- Kuş idi or Kuştu "It was a bird";

- Kuş muydu? "Was it a bird?"

Compound bases

The bases so far considered can be called "simple". A base in i- can be attached to another base, forming a compound base. One can then interpret the result in terms of English verb forms by reading backwards. The following list is representative, not exhaustive:

- Past tenses:

- continuous past: Geliyordum "I was coming";

- aorist past: Gelirdim "I used to come";

- future past: Gelecektim "I was going to come";

- pluperfect: Gelmiştim "I had come";

- necessitative past: Gelmeliydim "I had to come";

- conditional past: Gelseydim "If only I had come."

- Inferential tenses:

- continuous inferential: Geliyormuşum "It seems (they say) I am coming";

- future inferential: Gelecekmişim "It seems I shall come";

- aorist inferential: Gelirmişim "It seems I come";

- necessitative inferential: Gelmeliymişim "They say I must come."

By means of ise or -(y)se, a verb can be made conditional in the sense of being the hypothesis or protasis of a complex statement:

- önemli bir şey yapıyorsunuz "You are doing something important";

- Önemli bir şey yapıyorsanız, rahatsız etmeyelim "If you are doing something important, let us not cause disturbance."

The simple conditional can be used for remote conditions:

- Bakmakla öğrenilse, köpekler kasap olurdu "If learning by looking were possible, dogs would be butchers."