Natalician: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 414: | Line 414: | ||

* Loanwords also disobeys vowel harmony: ''Kofi'' ("Coffee") | * Loanwords also disobeys vowel harmony: ''Kofi'' ("Coffee") | ||

* Every grammatical prefix disobeys the vowel harmony aswell. | * Every grammatical prefix disobeys the vowel harmony aswell. | ||

==Parts of speech== | |||

There are nine '''parts of speech''' (''kurzuk felev'') in Natalician. | |||

#'''[[noun]]''' (''iztin'' "name"); | |||

#'''[[pronoun]]''' (''kahuče'' from Amaranian '''kayoûtshéy''', or ''reširnel iztinev'' "personal names"); | |||

#'''[[adjective]]''' (''oruvaš'' "quality"); | |||

#'''[[verb]]''' (''öhker'' from Amaranian '''eiyiker''', or ''dirzik'' "action"); | |||

#'''[[adverb]]''' (''randara''); | |||

#'''[[postposition]]''' (''hasah eřči'' "later addition"); | |||

#'''[[Grammatical conjunction|conjunction]]''' (''sedlek übeřre'' "sentence link"); | |||

#'''[[Grammatical particle|particle]]''' (''meres''); | |||

#'''[[interjection]]''' (''venzik rimizli'' "feeling manifester"). | |||

Only nouns and verbs are inflected in Natalician. An adjective can usually be treated as a noun, in which case it can also be inflected. Inflection can give a noun features of a verb such as person and tense. With inflection, a verb can become one of the following: | |||

* '''verbal noun''' (''öhkernel iztin''); | |||

* verbal adjective (''öhkernel oruvaš''); | |||

* '''verbal adverb''' (''öhkernel randara''). | |||

These have peculiarities not shared with other nouns, adjectives or adverbs. | |||

For example, some participles take a ''person'' the way verbs do. | |||

Also, a verbal noun or adverb can take a direct object. | |||

In Natalician, an ascriptive clause can be composed of a common noun standing alone as the Predicative, both the Subject and the Predicator being implicit and assumed from the situation. Example: | |||

:''köpek'' – "dog" | |||

:''Köpek.'' – "It is a dog." | |||

This means that both a noun and a verb can alone constitute an affirmative clause in Turkish, which is not the case in English. | |||

There are two standards for listing verbs in dictionaries. Most dictionaries follow the tradition of spelling out the '''infinitive form''' of the verb as the [[headword]] of the entry, but others such as the Redhouse Turkish-English Dictionary are more technical and spell out the '''stem''' of the verb instead, that is, they spell out a string of letters that is useful for producing all other verb forms through morphological rules. Similar to the latter, this article follows the stem-as-citeword standard. | |||

* '''Infinitive''': ''koşmak'' ("to run") | |||

* '''Stem''': ''koş-'' ("run") | |||

In Turkish, the verbal stem is also the second-person singular imperative form. Example: | |||

:''koş-'' (stem meaning "run") | |||

:''Koş!'' ("Run!") | |||

Many verbs are formed from nouns by addition of ''-le''. For example: | |||

:''köpek'' – "dog" | |||

:''köpekle'' – "dog paddle" (in any of several ways) | |||

The [[aorist]] tense of a verb is formed by adding ''-(i/e)r''. The plural of a noun is formed by suffixing ''-ler''. | |||

Hence, the suffix ''-ler'' can indicate either a plural noun or a finite verb: | |||

:''Köpek'' + ''ler'' – "(They are) dogs." | |||

:''Köpekle'' + ''r'' – "S/he dog paddles." | |||

Most adjectives can be treated as nouns or pronouns. For example, ''genç'' can mean "young", "young person", or "the young person being referred to". | |||

An adjective or noun can stand, as a modifier, before a noun. If the modifier is a noun (but not a noun of material), then the second noun word takes the inflectional suffix ''-i'': | |||

:''ak diş'' – "white tooth" | |||

:''altın diş'' – "gold tooth" | |||

:''köpek dişi'' – "canine tooth" | |||

[[Comparison (grammar)|Comparison]] of adjectives is not done by inflecting adjectives or adverbs, but by other means (described [[#Comparison|below]]). | |||

Adjectives can serve as adverbs, sometimes by means of repetition: | |||

:''yavaş'' – "slow" | |||

:''yavaş yavaş'' – "slowly" | |||

Revision as of 23:44, 14 November 2024

This article is private. The author requests that you do not make changes to this project without approval. By all means, please help fix spelling, grammar and organisation problems, thank you. |

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

| Natalician | |

|---|---|

| Nataldha | |

Flag of the Natalician Republic | |

| Pronunciation | [na.ta.ld.ja] |

| Created by | Hazer |

| Date | 2021 |

| Setting | Hazerworld |

| Native to | Natalicia; Firenia and the Kontamchian Islands |

| Ethnicity | Natalese |

| Native speakers | 37,123,487 (2021) |

Tinarian

| |

Early form | Old Natalician

|

Standard form | Standard Central Natalician (Kieneh Rasah Nataldha)

|

Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | Natalicia |

Recognised minority language in | Espidon, Amarania (Dogostania) |

| Regulated by | The Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics |

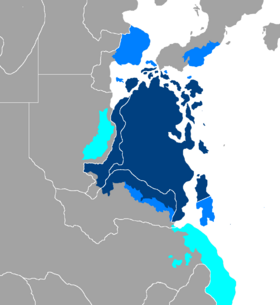

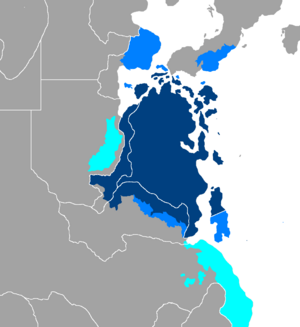

A map showing the distribution of (native and non-native) speakers of Natalician in Tinaria. Dark blue is native, light blue is secondary language speaker, and cyan is minorities. | |

Natalician (/nəˈtɑlɪʃən/; endonym: Nataldha [na.ta.ld.ja] or Natal Rettive /na.tal re.tːive/) is a North Kasenian language predominantly spoken in Central East Tinaria, specifically in Natalicia, Firenia, and North-East Nirania. Beyond Natalicia, it holds official status in Budernie, Nirania, and Kannamie, and is recognized as a minority language in East Espidon and within the Dogostanian community in Eastern Amarania. Natalician shares a close linguistic relationship with other North Kasenian languages, such as Espidan and Niranian.

Modern Natalician evolved from Old Natalician, which itself descended from an extinct, unnamed language spoken by the Natalo-Kesperian tribes. Today, Natalician stands as one of the world's most significant languages, boasting the highest number of speakers among the Kasenian languages, both as a native and a second language. Approximately 65 million people worldwide speak Natalician, including 37 million native speakers.

Natalician is characterised by its lack of grammatical cases, absence of grammatical genders, minimal irregularity, and a systematic grammar. Its orthography is straightforward, devoid of digraphs, diphthongs, or similar complexities, making it an accessible language to read and learn.

History

The earliest traces of the Natalician language date back to the year 334, featuring a vocabulary and grammar markedly different from its modern descendant. The history of the Natalician language is divided into three distinct periods: Classic Natalician (334–1203), Old Natalician (1203–1540), and Modern Natalician (1540–present). As of 2021, the language is estimated to be 1,687 years old.

Classic Natalician

Also known as Poetic Natalician or the Natalo-Kesperian Language, the earliest traces of this language are found solely in ancient poetry and inscriptions on recovered artifacts. However, the NACL (Natalician Academy of Classical Languages) considers these remnants insufficient to be deemed a complete or valid representation of the spoken Natalo-Kesperian language, largely due to the dominance of illiteracy in the pre-Killistic era and the overly formal nature of the vocabulary used in these writings.

Classic Natalician's vocabulary contains numerous direct elements from the early Proto-North-Kasenian language, which eventually faded during the migratory era. This decline was influenced by cultural clashes and the increasing incorporation of loanwords.

Unfortunately, no documents from the Classic Natalician period have survived. Consequently, there is no known evidence detailing the development of the language during this primary era.

Old Natalician

Reširi ägsös nör på tånåka if kelševi wez̊en fölsi sös.

“The people have the right to write and say what they please.”

With the dawn of the Killistic era, the Natalese tribes gained access to invaluable knowledge, brought by the ascension of their proclaimed king, Ribel Zömeri. This period marked a significant rise in literacy rates within the nascent and unified Natalese monarchy, which spanned from 1203 to 1834. During this era, the Natalician language saw its first instances of written records and experienced a flourishing of printed works.

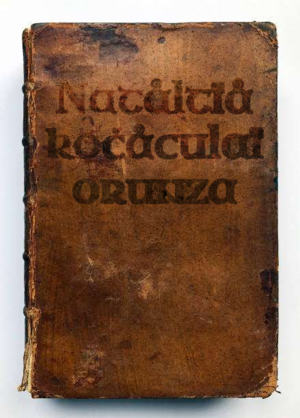

The earliest known book containing written evidence of the Natalician language is titled "Natåltïå kočåculaï orūnza" (Natalician Guide Book). This seminal work was authored and published by the late Ulun Cilesli Irkete in the year 1210. Subsequently, numerous documents have been preserved through generations and are now treasured artifacts housed in the Natalician Grand Museum of Literature and Artifacts in Celicia.

Many historians and literary scholars have debated the relationship between Classic and Old Natalician, with some arguing that they are identical. However, the scarcity of evidence has left these claims unresolved. Scholar Iček Friktinäm posits: "Old Natalician may be the result of the incorporation of new local loanwords, and the diverse dialects might have led to deviations from the Kasenian roots of the standard spoken Natalician of that time."

Old Natalician is characterized by significantly different grammar and vocabulary compared to modern Natalician. The most notable differences include the presence of vowel harmony and grammatical cases. The language featured four types of vowel harmony and three grammatical cases: Nominative, Accusative, and Genitive. Additionally, distinct suffixes and verb conjugations highlight the major grammatical differences.

Modern Natalician

Ťenałr tanakavsai der garla. Ťenałr nameš tanakavsai der ünete.

“History is written by the victor. Our history is written by the people.”

The Natalician language has been continuously evolving since the 15th century with the decline of the monarchy and the rise of Goz Hoz to power the next few centuries. Trades and exchanges between nations has allowed for a path to new loanwords added to the Natalician lexicon. This evolution continued until the establishment of the Republic in 1845 by Zafel Sörät Fortla, when the "Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics" was created and assumed responsibility for tracking the language's development.

Etymology

The name Natalicia, the Natalese and the Natalician language, originates from the Natala tribes of the Natalo-Kesperian community in central east Tinaria. The term derives from the Proto-Kasenian word Nåťåla, meaning "fairness." This evolved into Nåsåla in Old Natalician and eventually became Nasala in Modern Natalician.

Geographical Distribution

Natalician is spoken in the Natalician republic, the kingdom of Firenia, the northwestern camps of the Nirenian republic and as a minority language in Espidon and Amarania. The popularity of Natalician has increased following the Natalician Dispora program, resulting in an increase of demand for the language to be taught as a foreign language in most of Tinaria and the other three continents.

An exact global number of Natalician speakers is a matter of difference due to the several varieties of Natalician status as separate "languages" or "dialects" is disputed for political and linguistic reasons, including certain forms of Kasperian and Rufeic Natalician. With the inclusion or exclusion of said varieties, the estimate is approximately 40 million people who speak Natalician as a w:first language, 5 to 15 million speak it as a w:second language, and 40 to 50 million as a w:foreign language. This would imply approximately 85 to 105 million Natalician speakers worldwide.

Natalician sociolinguist Mezred Siförtah estimated a number of 150 million Natalician foreign language speakers without clarifying the criteria by which he classified a speaker.

Tinaria

As of 2024, about 40 million people, or 12% of the Tinarian Union's population, spoke Natalician as their mother tongue, making it the fourth-most widely spoken language on the continent after English, Secaltan and Amaranian, the fourth biggest language in terms of overall speakers, as well as the third most spoken native language.

Natal Koman

The area in central east Tinaria where the majority of the population speaks Natalician as a first or second language and has Natalician as a (co-)official language is called the "Natal Koman (Natalician for: 'Natalese World')". Natalician is the official or co-official language of the following countries:

- Natalicia (official)

- Firenia (official)

- The Kontamchian Islands (official)

- Søfrøzkev, Niččišey and Vørkek regions of Nirenia (co-official)

- Province of Trumuyet of Tuggol (co-official)

- The Islands of Kannamay, Binjes and Vurvuda (co-official)

Outside the Natal Koman

Natalician is a recognised minority language in the following countries:

- Espidon (in the provinces of Zafur and Iktišek)

- East of the Federal Dogostanian Republic in Amarania

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | |||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s θ | ʃ | h | ||||

| voiced | v | z ð | ʒ | ʁ | |||||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡ʃ | |||||||

| voiceless | d͡ʒ | ||||||||

| Approximant | semivowel | j | w | ||||||

| lateral | l | ||||||||

- The phoneme /ʒ/ is usually realised as /dʒ/ in many dialects. In the island dialects, it is replaced with /d͡ʒ/ when it occurs word-initially.

- /l/ can undergo delateralisation in most dialects if preceeded by /i/ - for example, senil ("problem") is pronounced /se.nij/ rather than /se.nil/.

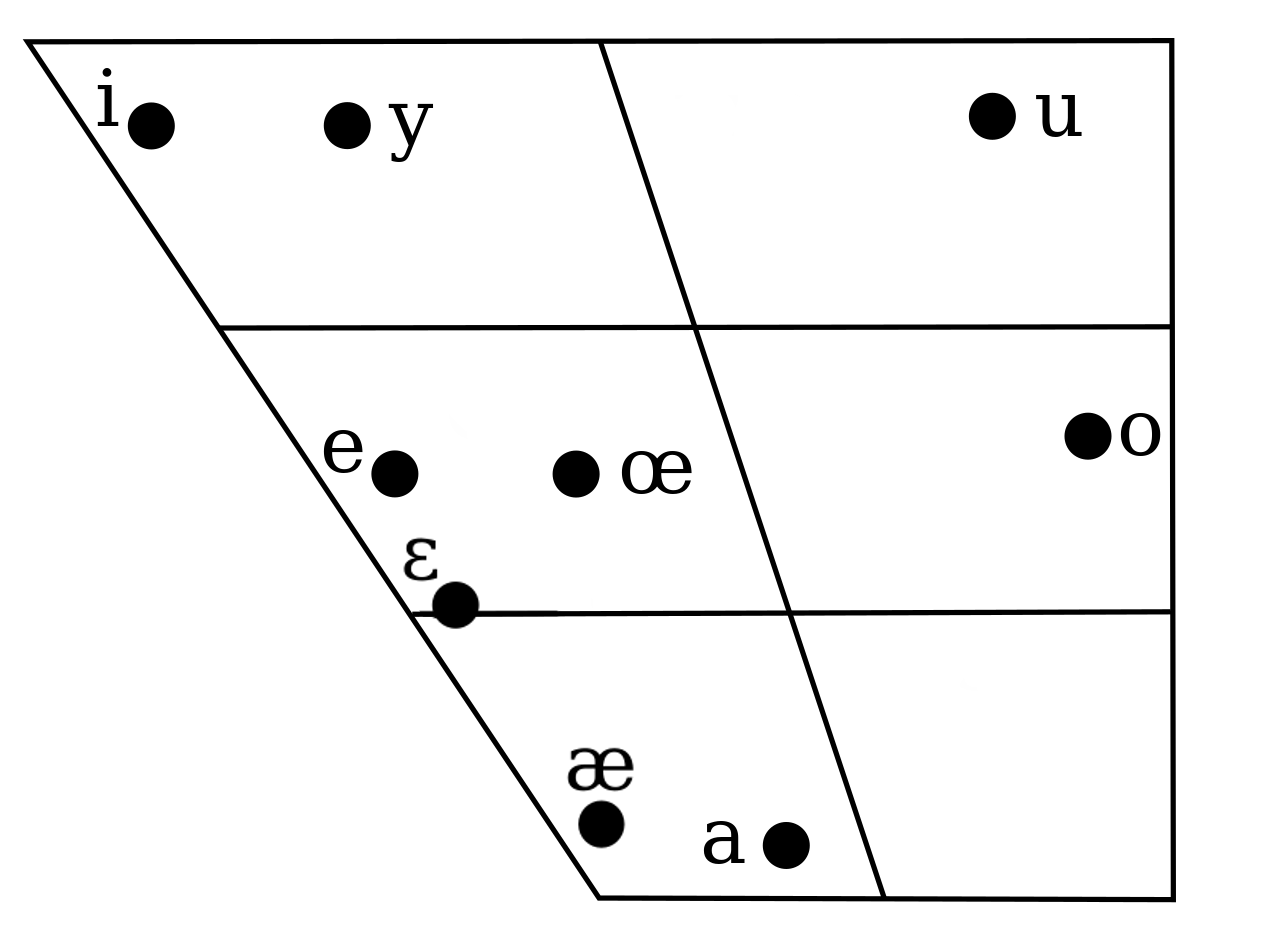

Vowels

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |

| Close | i | y | u | |

| Near-open | æ | |||

| Open | e | œ | a | o |

The vowels of the Natalician language are, in their alphabetical order, ⟨a⟩, ⟨ä⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨ü⟩.

The Natalician vowel system can be considered as being three-dimensional, where vowels are characterised by how and where they are articulated focusing on three key features: front and back, rounded and unrounded and vowel height.

NOTE: When the vowels /i/, /u/ precede or succeed another vowel, they become /j/, /w/ respectively. If both vowels meet one another, only the /i/ will transform into a /j/ while the /u/ remains unchanged.

Orthography

Alphabet

Natalician has a straightforward orthography, meaning regular spelling with (almost) no diphthong or digraph or anything of the sort. In linguistic terms, the writing system is a phonemic orthography.

Standard Natalician alphabet

| Letter | Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Aa | a [a] | /a/ |

| Ää | ä [æ] | /æ/ |

| Bb | be [be] | /b/ |

| Cc | ce [d͡ʒe] | /d͡ʒ/ |

| Čč | če [t͡ʃe] | /t͡ʃ/ |

| Dd | de [de] | /d/ |

| Ďď | ďe [ðe] | /ð/ |

| Ee | e [e] | /ɛ/, /e/ |

| Ff | ef [ɛf] | /f/ |

| Gg | ge [ɡ] | /g/ |

| Hh | ha [ha] | /h/, /j/ |

| Ii | i [i] | /i/, /j/ |

| Jj | je [ʒe] | /ʒ/ |

| Kk | ka [ka] | /k/ |

| Ll | el [ɛl] | /l/ |

| Łł | girbit el [gir.bit ɛl] | /ː/ |

| Mm | em [ɛm] | /m/ |

| Nn | en [ɛn] | /n/ |

| Oo | o [o] | /o/ |

| Öö | ö [œ] | /œ/ |

| Pp | pe [pe] | /p/ |

| Rr | er [ɛr] | /r/ |

| Řř | eř [ɛʁ] | /ʁ/ |

| Ss | es [s] | /s/ |

| Šš | eš [ɛʃ] | /ʃ/ |

| Tt | te [te] | /t/ |

| Ťť | ťe [θe] | /θ/ |

| Uu | u [u] | /u/ |

| Üü | ü [y] | /y/ |

| Vv | ve [ve] | /v/ |

| Ww | wa [wa] | /w/ |

| Zz | ze [ze] | /z/ |

- The letter that is called Girbit El ("Silent L"), written ⟨Ł⟩ in Natalician orthography, represents vowel lengthening. It never occurs at the beginning of a word or a syllable, always follows a vowel and always preceeds a consonant. The vowel that preceeds it is lengthened.

- The letter ⟨H⟩ in Natalician orthography represents two sounds: The /h/ sound, and the /j/ sound. If the letter ⟨H⟩ is located at the beginning of the (non-compound) word, it takes the /h/ sound, otherwise it takes the /j/ sound. (e.g. Hiloh /hi.loj/ "Hello", Konah /ko.naj/ "Beautiful", Haz /haz/ "This")

Grammar

Consonant harmony

Natalician orthography reflects voice sandhi voicing, a form of consonant mutation with two consonants that meet, and the second is voiced and the first is unvoiced. The first unvoiced consonant [p t f ʃ t͡ʃ θ k s] is voiced to [b d v ʒ d͡ʒ ð ɡ z], but the orthography remains unchanged.

- Kütdüs (you drink) realises the /t/ as a /d/ due to the voiced consonant that follows; hence, it becomes /kydː.ys/.

- Äzäpzik (announcement) realises the /p/ as a /b/; hence, it becomes /æ.zæb.zik/.

NOTE: The only time a voiced consonant gets devoiced is when the voiced-voiceless pairs meet and the voiced consonant preceeds the voiceless one, resulting in a gemination of the voiceless consonant: Lüzševi /lyʃː.e.vi/ - Özse /œsː.e/ - Kodtos /kotːos/

Vowel harmony

| Natalician Vowel Harmony | Front Vowels | Back Vowels | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |||||||

| Vowel | ä | e | i | ö | ü | a | o | u | ||

| Type Ĭ (Backness + Rounding) | i | ü | a | u | ||||||

| Type Ĕ (Backness) | e | o | ||||||||

The principle of vowel harmony

- If the first vowel of a word is a back vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a back vowel; if the first is a front vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a front vowel.

- If the first vowel is unrounded, so too are subsequent vowels.

The second and third rules minimize muscular effort during speech. More specifically, they are related to the phenomenon of labial assimilation: If the lips are rounded (a process that requires muscular effort) for the first vowel they may stay rounded for subsequent vowels. If they are unrounded for the first vowel, the speaker does not make the additional muscular effort to round them subsequently.

Grammatical affixes have "a chameleon-like quality" and obey one of the following patterns of vowel harmony:

- Twofold (-e/-o): The article, for example, is -(v)e after front vowels and -(v)o after back vowels.

- Fourfold (-i/-a/-ü/-u): The verb infinitive suffix, for example, is -i or -a after unrounded vowels (front or back respectively); and -ü or -u after the corresponding rounded vowels.

- Type & 'and': The adjectival passive voice suffix, for example, is -t&t, the & being the same vowel as the previous one.

Practically, the twofold pattern (usually referred to as the type Ĕ) means that in the environment where the vowel in the word stem is formed in the front of the mouth, the suffix will take the e form, while if it is formed in the back it will take the o form. The fourfold pattern (also called the type Ĭ) accounts for rounding as well as for front/back. The type & pattern is the reppetition of the same last vowel. The following examples, based on the verbal noun suffix -zĭk, illustrate the principles of type Ĭ vowel harmony in practice: Ähräzik ("Swimming"), Okzuk ("Knowledge"), Ianzak ("Eating"), Nörzük ("Living").

Exceptions to vowel harmony

These are four word-classes that are exceptions to the rules of vowel harmony:

- Native, non-compound words, e.g. Ela "then", Čela "drink", Ťehozuk "discussion"

- Native compound words, e.g. Pave "for what"

- Foreign words, e.g. many English loanwords such as Sertifikäht (certificate), Hospitol (hospital), Komphuter (computer)

- Invariable prefixes / suffixes:

| Invariable prefix or suffix | Natalician example | Meaning in English | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| –(v)iš | üčiš | "exit" | From üč "leave" |

| öz- | özhaša | "to return" | From haša "to come" |

| gik- | gikdönšetet | "uncleaned" | From dönšetet "cleaned" |

Note

- A native compound does not obey vowel harmony: Ras+cezil ("city center"—a place name)

- Loanwords also disobeys vowel harmony: Kofi ("Coffee")

- Every grammatical prefix disobeys the vowel harmony aswell.

Parts of speech

There are nine parts of speech (kurzuk felev) in Natalician.

- noun (iztin "name");

- pronoun (kahuče from Amaranian kayoûtshéy, or reširnel iztinev "personal names");

- adjective (oruvaš "quality");

- verb (öhker from Amaranian eiyiker, or dirzik "action");

- adverb (randara);

- postposition (hasah eřči "later addition");

- conjunction (sedlek übeřre "sentence link");

- particle (meres);

- interjection (venzik rimizli "feeling manifester").

Only nouns and verbs are inflected in Natalician. An adjective can usually be treated as a noun, in which case it can also be inflected. Inflection can give a noun features of a verb such as person and tense. With inflection, a verb can become one of the following:

- verbal noun (öhkernel iztin);

- verbal adjective (öhkernel oruvaš);

- verbal adverb (öhkernel randara).

These have peculiarities not shared with other nouns, adjectives or adverbs. For example, some participles take a person the way verbs do. Also, a verbal noun or adverb can take a direct object.

In Natalician, an ascriptive clause can be composed of a common noun standing alone as the Predicative, both the Subject and the Predicator being implicit and assumed from the situation. Example:

- köpek – "dog"

- Köpek. – "It is a dog."

This means that both a noun and a verb can alone constitute an affirmative clause in Turkish, which is not the case in English.

There are two standards for listing verbs in dictionaries. Most dictionaries follow the tradition of spelling out the infinitive form of the verb as the headword of the entry, but others such as the Redhouse Turkish-English Dictionary are more technical and spell out the stem of the verb instead, that is, they spell out a string of letters that is useful for producing all other verb forms through morphological rules. Similar to the latter, this article follows the stem-as-citeword standard.

- Infinitive: koşmak ("to run")

- Stem: koş- ("run")

In Turkish, the verbal stem is also the second-person singular imperative form. Example:

- koş- (stem meaning "run")

- Koş! ("Run!")

Many verbs are formed from nouns by addition of -le. For example:

- köpek – "dog"

- köpekle – "dog paddle" (in any of several ways)

The aorist tense of a verb is formed by adding -(i/e)r. The plural of a noun is formed by suffixing -ler. Hence, the suffix -ler can indicate either a plural noun or a finite verb:

- Köpek + ler – "(They are) dogs."

- Köpekle + r – "S/he dog paddles."

Most adjectives can be treated as nouns or pronouns. For example, genç can mean "young", "young person", or "the young person being referred to".

An adjective or noun can stand, as a modifier, before a noun. If the modifier is a noun (but not a noun of material), then the second noun word takes the inflectional suffix -i:

- ak diş – "white tooth"

- altın diş – "gold tooth"

- köpek dişi – "canine tooth"

Comparison of adjectives is not done by inflecting adjectives or adverbs, but by other means (described below).

Adjectives can serve as adverbs, sometimes by means of repetition:

- yavaş – "slow"

- yavaş yavaş – "slowly"

Pronouns

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| Personal Pronoun | Nei | On | Sü | Namše | Daš | So |

| Object Pronoun / Possessive Determiner | In | Un | Süs | Nameš | Daša | Soz |

| Possessive Pronoun | Ini | Onu | Süzü | Nameše | Dašo | Sozun |

In a sentence, the possessive determiner will always succeed the object. The object pronoun usually comes after the verb (Haz ensei ert in - This is my father).

Verbs

Stems of verbs

Many stems in the dictionary are indivisible; others consist of endings attached to a root.

Verb-stems from nouns

Many verbs are formed from nouns or adjectives with -šĕ:

Noun Verb ergem "negativity" ergemše- "negate" an "one" anšo- "unite" kel "word" kelše- "say"

Voice

A verbal root, or a verb-stem in -šĕ, can be lengthened with certain extensions. If present, they appear in the following order, and they indicate distinctions of voice:

Extensions for voice Voice Ending Example Reflexive -(ĭ)r; kark (wash); karkar ([take a] shower) Reciprocal -cĕ; dol (send); dolco (exchange) Causative -(&)z; ian (eat); ianaz (feed) Passive -(ĭ)v; artan (help); artanav (be helped)

These endings might seem to be inflectional in the sense of the Template:Section link above, but their meanings are not always clear from their particular names, and dictionaries do generally give the resulting forms, so in this sense they are constructive endings.

The causative extension makes an intransitive verb transitive, and a transitive verb factitive. Together, the reciprocal and causative extension make the repetitive extension -cĕz.

Verb Root/Stem New Verb Voice dol "send" dolco "exchange" -co (reciprocal) doluv "be sent" -uv (passive) ver "Fix (something)" verir "fix oneself" -ir (reflexive) verce "correct each other" -ce (reciprocal) fäs "die" fäsäz "kill" -äz (causative) küt "drink" kütde "do not drink" -de (negative)

Questions

The interrogative particle a precedes the verb in the interrogative form:

- A hašzar? "Are you coming?"

- A haštaz? "Did you come?"

Optative mood

Usually, in the optative (öštüküh), there is one series of endings to express something wished for:

Optative Moods Number Person Ending Example English Translation Singular 1st -deriz Nörderiz "May I live" 2nd -derid Nörderid "May you live" 3rd -deris Nörderis "May [her/him/it] live" Plural 1st -derizis Nörderizis "May we live" 2nd -deridis Nörderidis "May you live" 3rd -derisis' Nörderisis "May they live"

Compound bases

- Past tenses:

- continuous past: Entiz hašzai or Haštazar "I was coming";

- aorist past: Entiz haštaz "I used to come";

- future past: Entiz hašvaz "I was going to come";

- necessitative past: Entiz ekin hašzai "I had to come";

- conditional past: Nu ulan haštaz "If only I had come."

- Inferential tenses:

- continuous inferential: Enzei hašlozu "It seems (they say) I am coming";

- future inferential: Ekin hašlovuz "It seems I shall come";

- aorist inferential: Hašlozu "It seems I come";

- necessitative inferential: Ekin hašlozu "They say I must come."

Vocabulary

Phrasebook

Natalician common words and phrases useful for learners.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||