Fjämsk: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1,698: | Line 1,698: | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[category: Conlang]] | |||

Revision as of 21:17, 19 June 2016

A simple grammar of The Femmish Tongue as it is spoken on the streets, in modern times, in the city of Rödby the capital of The Republic of Femland.

@fjaemsk on Twitter™

UNDER CONSTRUCTION - please do not edit or export this document.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE FEMMISH LANGUAGE

- Femmish (known as fjämsk [fjɛmʃ] or deð fjämsk språgið [dɪθ fjɛmʃ ’spʁɔ:xɪθ] in the language itself) is a North Germanic language, spoken by the 550,700 inhabitants of the island nation of Femland. It is a member of the Northern Germanic (Scandinavian) family of languages and is largely mutually intelligible with Norwegian, Danish and Swedish. Femmish is a descendant of Old Norse, the common language of the Germanic peoples living in Scandinavia during the Viking era. Femmish has also absorbed vocabulary from Dutch with whom the island was a trading partner during the middle ages.

- The name Fjämö [fjɛ:mœ], which translates literally as Fjäm Island, is possibly from the old Norse fjaraland meaning “land of the ebb-tide” as parts of the island are low-lying and the seasonal tides cause the sea to go out a long way exposing vast beaches and mudflats. Another possible explanation, at least according to Icelandic historian Magnus Rasmusson’s book, is that one of the earliest Scandinavian settlers was a farmer called Fiamm and the settlement grew up around his homestead becoming known simply as “Fiamm’s island” or “Fiammey”. Fiamm himself has become something of a folk-hero among the Femmish and although accounts of his life are entire apocryphal (as with Robin Hood in England), people still celebrate him as their nation’s founding father.

- In English, the name of the island has always been simply Femland which is likely to have been passed down from Dutch traders who knew the island as Veemland as early as the 11th century. The Germans referred to it on early maps as Fehmland[1], and in Icelandic it is referred to as Fémmey.

- Although history shows us that the Vikings had settlements in Femland by the middle ages, these were merely fleeting fishing camps and summer visitations and there is no evidence of permanent Scandinavian settlers until Swedes began to arrive on Femland’s northern coastline by 1300. In fact, there is some evidence that the earliest permanent settlers on Femland were Irish monks who established a monastery as early as the tenth century in an area now known as Klosterið [’klo:stəʁɪθ] where substantial medieval ruins stand to this day.

- Standard Femmish (standardfjämsk, also known colloquially as Rödbysmål as it is the form spoken in Rödby, the capital city), is the national language that evolved from various dialects in the 18th century and was well established by the beginning of the 20th century.

- The spoken and written language today is mostly uniform and standardized but there are still some variations of the spoken language in rural areas, and a noticeable difference in accent and vocabulary on Norðlandið known as norðlandsk [nɔ:θlɑnʃ].

- One notable feature of modern Femmish is that unlike in Swedish and Norwegian, the tonal word accent that distinguishes certain minimal pairs is not present in Femmish.

- The standard word order is subject–verb–object (svo), though this can often be changed to stress certain words or phrases or in certain adverbial sentences.

- Femmish morphology is similar to English; that is, words have comparatively few inflections. There are two genders, the so-called common and neuter; often known as neuter and non-neuter or ð-words and n-words.

- There are two grammatical cases, and a distinction between plural and singular.

- Adjectives are compared as in English, and are also inflected according to gender, number and definiteness.

- The definiteness of nouns is marked primarily through suffixes (endings), complemented with separate definite and indefinite articles.

PHONOLOGY

STANDARD PRONUNCIATION

- The pronunciation of Femmish heard in the capital town of Rödby (known colloquially as Rödbysmål), is considered to be the standard pronunciation of the language. The language does not have much phonological diversity across the whole nation apart from a noticeable difference in accent and vocabulary in the dialect known as norðlandsk [nɔ:θlɑnʃ] spoken around the town of Norðvik.

VOWELS

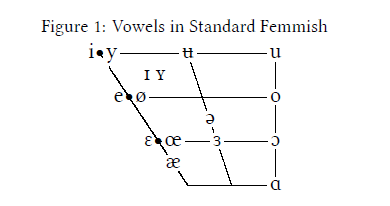

- Femmish, unlike English, does not have a lot of complex vowels within words. There are front and back, long and short combinations of vowels.

VOWEL LENGTH

- The general rule of vowel-length is that any vowel which stands in an open-syllable is long whereas a vowel in a closed-syllable is short. A monosyllabic word usually has a long vowel unless the word ends in a doubled-consonant. A monosyllabic word which ends in a vowel, is always pronounced long. Unless preceding another vowel, all unstressed vowels are short.

- bot [bo:t] salary, is pronounced long

- bo [bu:][2] to reside, is pronounced long

- del [de:l] department, is pronounced long

- fri [fʁi:] free, is pronounced long

- frass [fʁɑs] strawberry, is pronounced short

- full [fɶl] full, is pronounced short

- hemel [he:məl] heaven, has a long root vowel and an unstressed final vowel.

DIPHTHONGS

- When following a vowel at the end of a syllable, v often reduces to a semi-vowel creating a diphthong or glide, /ɑ̞ʊ/ which is realized in words such as ravn [’ʁɑ̞ʊn] (raven) and avn [’ɑ̞ʊn] (ram) as well as in automobil [’ɑ̞ʊto.mobi:l] (automobile) and revmatisme [rɛ̞ʊmɑtismə] (rheumatism).

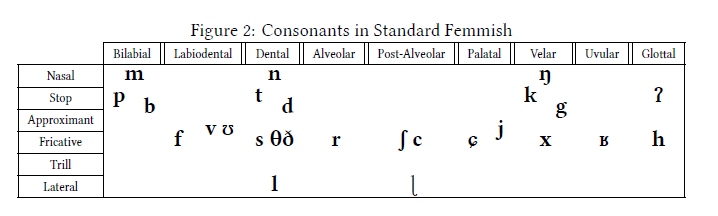

CONSONANTS

|c|c|c|l| & IPA & Example & Explanations

b & [b] & boll & devoices to [p] at the end of words

c & [ts] & centrum &

& & dotter &

& & stad & devoices to [t] at the end of words

ð & [ð] & glað & devoices to [θ] at the end of words. ð can never appear at the beginning of a word

f & [f] & förrig &

& [g] & gammel & always a hard [g] as in English “get”

& [x] & rogen & becomes [x] between two vowels

& [j] & göre; görsom & see the section on allophony, below

& [w] & säg; ög & becomes [w] or vanishes completely, at the end of words

h & [h] & harfisk &

j & [j] & jogurt &

& [k] & kartoffel &

& [tʃ] & kött &

& [c] & skatt & the combination [sc] is only found at the beginning of words

& [l] & land &

& [ɭ] & mjölk & becomes [ɭ] before another consonant

m & [m] & medlem &

& [n] & nuskelse &

& [ŋ] & säng; dögn & see the section on allophony, below

p & [p] & på &

& [ʁ] & frass &

& [r] & händer &

& [s] & siðan & the Femmish s is never voiced to [z], as it sometimes is in English

& [ʂ] & sjuk &

t & [t] & tenn &

þ & [θ] & þing & þ only ever appears at the begining of a word or part of a compound word

v & [v] & venn & see the section on allophony, below

x & [ks] & växel & the Femmish x is never voiced to [gz], as it often is in English

ALLOPHONY

Allophony is the variation in the phonetic realizations of a phoneme. Although Femmish is mostly a phonetically regular language, when different consonants come into contact with one another, their sounds often change unexpectedly (at least to English speakers) depending on their placement within the word.

The best way to illustrate this is with examples:

b becomes voiced to [p] at the end of a word or syllable as in knab [knɑp] (button) and knabbord [knɑp.bɔ:ʁ] (keyboard)

'd vanishes in the combinations -nd and -rd at the end of a word, as in land [lɑn:] (land), bord [bɔ:ʁ] (table), and ord [ɔ:ʁ] (word); however it reappears as /d/ ' when the word is suffixed by a vowel, as in landið [’lɑndɪθ] (the land), bordið [bɔ:ʁdɪθ] (the table), and ordið [ɔ:ʁdɪθ] (the word).

dj becomes [dʒ] as in djup [dʒu:p] (deep)

g becomes [j] before ä/e/i and ö as in gäta [’jɛ:tɑ] (to guard)

g becomes [w] or is lost completely following ä/e/i and ö at the end of a word as in ög [ɶw] (eye), and sig [siw] (victory) and in speech even the [w] may become swallowed at the end of a word such as in the pronoun eg which may become [æɪ]. After a vowel and before ä/e/i and ö, g becomes [x] as in hage [’ha:xə] (flowerbed), and säga [’sɛ:xɑ] (to say)

the combination gn, is always pronounced [ŋn] as in regn [re:ŋn] (rain) and dögn [dɶ:ŋn] (a 24 hour period)

the combination ng, is always pronounced [ŋ] as in haning [’ha:nɪŋ] (rooster) and stingande [stɪŋɑndə] (pungent). It is never pronounced [ŋg] as in English finger

both hj and kj become [ʂ] as in hjol [ʂo:l] (wheel), hjälp [ʂɛlp] (help) and kött [ʂɶt] (meat)

single l remains [l] at the end of a word as in hjol [ʂo:l] (wheel) and doubled ll is always held longer as in snäll [snɛl:] (fast). before another consonant, l often becomes vocalized to [ɭ] as in mjölk [mjɶɭk] (milk) and såld [sɔɭt] (gallon)

lj becomes [j] as in ljus [ju:s] (light) and pälj [pɛ:j] (knife)

r which is usually gutteral [ʁ], can become [r] before another consonant as in merje [merjɛ] (maiden) and att mörda [ɑt mɶrdɑ] to murder

sj also becomes [ʂ] as in sjuk [ʂu:k] (sick) and kråsj [kʁɔʂ] (pear-tree)

at the beginning of a word, sk becomes [sc] as in skatt [scɑt] (tax) except before ä/e/i and ö when it becomes [ʃ] as in sköd [ʃɶt] (swift). Elsewhere it becomes [ʃ] as in människ [mɛn.nɪʃ] ( masculine). -rsk becomes [ʃ] as in norsk [nɔ:ʃ] (Norwegian) and -skt becomes [ʃt] as in fiskte [fɪʃtə] (fished)

stj becomes [ʃ] at the beginning of syllables as in stjärna [ʃɛrnɑ] (star)

tj becomes [tʃ] as in tjald [tʃɑlt] (tent)

v becomes [f] when word-final as in körv [kɶrf] (plaza), and before another consonant as in vred [fʁet] (angry) and beskrevning [bəʃʁe:fnɪŋ] (description) but it becomes a semi-vowel in a few rare words such as avn [ɑʊn] (ram) and övn [ɶwn] (oven) and it also in the prefix av [ɑʊ] but only when it is adjoined to the root word as in avskatt [ɑʊ’scɑt] (duty)

a frequent irregularity is the ending -ti which is often pronounced [tsi] and is found in words such as reparati [ʁəpa:ʁɑtsi] (repair) and politi [poli:tsi] (police)

GEMINATION

- Gemination, or consonant elongation, happens when a spoken consonant is pronounced for an audibly longer period of time than a short consonant. In general, consonants in Femmish are geminated if they are written doubled, except if they are word-final:

- rogen (the rye) [ʁo:xən] → roggen (the rug) [ʁox:ɪn]

- frass [fʁɑs] (strawberry) the doubled -ss is not geminated, coming at the end of the word, but frassen [fʁɑs:ɪn] (the strawberry) the doubled -ss is geminated as it precedes another syllable

EXCEPTIONS TO THE RULES

- There are some words which are pronounced contrary to the phonetic rules and must simply be learned.

- inte (not) is usually pronounced as [ɪntʃ]

- også (also) is usually pronounced as [ɔsɔ:]

- ov (too) is usually pronounced as [uw]

- The definite article noun endings -en, -ið and -ene are pronounced different than these combinations would be in other words.

- mannen (the man) is pronounced as [mɑn:ɪn]

- husið (the house) is pronounced as [hu:sɪθ]

- husene (the houses) is pronounced as [hu:sɪnə]

STRESS

- Femmish makes abundant use of semantic stress, as in English, that is, words can be stressed arbitrarily in sentences depending on their emphasis related to the meaning of the phrase.

- Most native Scandinavian words (the bulk of the core vocabulary) are stressed on the root syllable, which is usually the first syllable of the word. Femmish follows this pattern, so that the word tvåmal would be pronounced [tvɔ:mɑl].

- In Femmish compound words, secondary stress falls on the second stem so that sporvagn would be pronounced [’sporˌvɑŋn].

- Native words may also be stressed on the second or later syllable if certain unstressed prefixes are added (particularly in verbs).

- Non-root stress is common in loanwords, as such words are generally borrowed with the stress placement unchanged.

MORPHOLOGY

PRONOUNS

PERSONAL PRONOUNS

- The Femmish personal pronoun system is almost identical to that of English. Pronouns inflect for person, number, and, in the third person singular, gender. Differences with English include the inclusion in Femmish of a separate third-person reflexive pronoun sig (himself, herself, itself, themselves) analogous to French se, and the maintenance of distinct 2nd person singular þu (thou), I (you, plural), and objective forms of those, which have all merged to you in English. The reflexive forms are not used for the first and second person, although sjölv (self) and egen/egeð/egna (own) may be used for emphasis, and there are no absolute forms for the possessive.

- Femmish uses the pronoun man as an impersonal pronoun in much the same way that German uses it, and French uses on.

- man ankommer kvardags klocken tiu → one arrives at ten o’clock every day

- As in many other European languages, the second person plural form (þi) is also used when formally addressing an individual. Children will use this form when addressing teachers, grandparents, their friends’ parents and most other adults. Adults themselves will use it to address officials, business associates or their boss. It is common for acquaintances, once acquainted, to revert to þu as a sign of mutual acceptance and trust.

- þi is often written with a capital letter in correspondence as a mark of respect.

- On notices and in advertisements, either form may be used depending on who the target audience is intended to be.

|c|c|c|c|c|c| & Nominative & Oblique &

1 & eg & mig & min & mið & mina

2 & þu & þig & þin & þið & þina

& han & hem &

& hon & har &

& den|deð & sig & sin & sið & sina

1 & vir & vus & vor & vort & vära

2 & þi & þus & þor & þort & þora

3 & de & dem &

POSSESSIVE PRONOUNS

- Femmish possessives do not behave in a uniform way. The form of some possessives relates to the gender and number of the possessed item. The other possessives have only one form, which consequently is used for all genders and for singular and plural objects:

- min bil (my car); mið efternavn (my surname); mina låg (my onions)

- þin bil (your car); þið efternavn (your surname); þina låg (your onions)

- hans bil (his car); hans efternavn (his surname); hans låg (his onion or onions)

- hons bil (her car); hons efternavn (her surname); hons låg (her onion or onions)

- sin bil (its car); sið efternavn (its surname); sina låg (its onions)

- vor bil (our car); vort efternavn (our surname); vära låg (our onions)

- þor bil (thy car); þort efternavn (thy surname); þora låg (thy onion or onions)

- derra bil (their car); derra efternavn (their surname); derra låg (their onion or onions)

- In the 3rd-person, the forms sin, sið, and sina, are used when the possessed noun reflects back to the subject of the phrase. For example in English, if one says “The man broke his arm”, although it is grammatically ambiguous, it is usually understood by convention whose arm was broken but it is not immediately obvious whether he broke his own arm or someone else’s!

- In Femmish, this is overcome by replacing hans and hons with sin, sið and sina (depending on gender and number) if the patient of the action is the same person as the agent performing the action.

- han brötte armen hans (he broke his arm, meaning someone else’s rather than his own)

- han brötte armen sin (he broke his [own] arm)

- When speaking of body parts, it is usual for the possessive pronoun to follow the noun, which is always presented in the definite form. This is a peculiarity of the language which foreigners often overlook. While you will be fully understood if you were to say han brötte sin armen it would sound odd to a native speaker.

INDEFINITE PRONOUNS

- Indefinite pronouns are pronouns whose antecedents are unspecified persons, places, things, and ideas. An antecedent is the noun, noun phrase, or noun clause that a pronoun replaces. Indefinite pronouns with antecedents that refer to a person or people are also referred to as impersonal pronouns. Indefinite pronouns often appear in impersonal sentence constructions, or sentences that make general statements without a specified grammatical agent.

DEÐ → it

- deð är bra → it is fine

- deð ankom klocken tiu → it arrived at ten o’clock

NAKAN → common: anyone; anybody; someone; somebody | neuter: something; anything; somewhat | plural: any; some

- har nakan sett min bror? → has anyone seen my brother?

- har þu sett nakað? → have you seen anything?

- har þu sett naka? → have you seen any?

- nakað ankom för þu! → something arrived for you!

INGEN → common: nobody; no-one | neuter: nothing; no kind of | plural: none → ingenþing

- har ingen sett min bror? → has nobody seen my brother?

- har þu sett ingeð? → have you seen nothing?

- önskar þu inga? → do you want none?

- önskar þu ingenþing? → do you want nothing?

SOMME → some (synonymous with naka)

- önskar þu somme? → do you want some?

- somme geller hem, somme ej[3] → some like him, some don’t

MARGEN → many; much

- ått þu margeð? → did you eat many (unspecified things)?

- ått þu margen? → did you eat much?

- eg såg marga → I saw many (of them)

- margen gäf! → much luck!

ANDEN → common: another | neuter: anything else | plural: others

- en anden må ha deð! → another must have it!

- kan eg få eð andeð äpple? → can I have another apple?

- har þu andeð með? → do you have anything with (you)?

- vir bor på eð andeð hotell → we are staying at another hotel

- andra prövar, somme ej → others try, some don’t

ALL → common: all | neuter: everything | plural: all; everybody

- all Jarðen är gamla → all the Earth is old

- allð är brött → everything is broken

- alla har sett min bror → everyone has seen my brother

KVAR → each; every

- kvarð har sið bröd → each has its own bread

- kvar kan hjälpes → everyone can be helped

- enkvar → anyone; any kind

- enkvar kan ha bröd→ anyone can have bread

- enkvarð kan köbes → any kind can be bought

QUANTIFIER PRONOUNS

- In English grammar, a quantifier is a word (or phrase) which indicates the number or amount being referred to. It generally comes before the noun (or noun phrase). Femmish has the following quantifier pronouns:

NOG → enough/plenty

- nog är nog → enough is enough

LITEÐ → little

- liteð är kent om þenna period av sagafräðið → little is known about this period of history

MINDRE → less

- mindre är kent om þenna period av sagafräðið → less is known about this period of history

MARGEÐ → much

- margeð blev rätt på mödeð → much was discussed at the meeting

MARGA → many

- marga blev valt → many were chosen

MER → more

- mer är bädre → more is better

MEST → most

- mest var fyl → most was rotten

FLERA → several

- flera börn blev valt → several children were chosen

FÅR → few

- får blev valt → few were chosen

FÄRRE → fewer

- färre går i kirkjan nudags → fewer are going to church these days

THE EXPLETIVE PRONOUN

- Where English uses “there is” or “there are”, Femmish uses a passive construction with the verb att finna. Where English uses “there” with the verb in the plural, Femmish uses deð:

- deð finns marga folk i högskolan → there are many people in the high-school (lit. there are found...)

- deð finns bröd på bordeð → there is bread on the table (lit. there is found...)

- deð fanns marga folk þarðan → there were many people from there (lit. there were found...)

DEMONSTRATIVE PRONOUNS

- Demonstratives are words that direct your attention to certain objects. Some of the demonstratives agree in gender and number with the noun they are connected to, others do not.

ÞENNA/ÞETTE/ÞESSA

- Þenna/þetta (“this”, depending on gender), þessa (“these”, regardless of gender) indicate that the person, object or idea spoken about is close in time or space. When no specific noun is given, þetta is used as the assumed neuter form.

- þenna fruktsaft är kalda → this fruit juice is cold

- þetta kalså smakar läcker → this pancake tastes delicious

- þessa skor är ov stor → these shoes are too big

- þetta smakar läcker → this tastes delicious

DEN/DEÐ/HINN

- Den/deð, (that, depending on gender), hinn (those, regardless of gender) indicate that the person, object or idea spoken about is distant in time or in space. When no specific noun is given, deð is used as the assumed neuter form.

- den frugtsaft är kalda → that fruit juice is cold

- deð körb har löckar → that boot has holes

- men hinn är perfekt → but those are perfect

- deð är kaldt → that is cold

- Den and deð are also so called determinative pronouns. A determinative pronoun refers forward, which means that we don’t have a lot of information yet and we will now get more information. The new information we usually get in a relative subordinate clause. Compare this to a noun in definite form (bilen, husið etc), which refers backward – we know which house or car we’re talking about, we have information about it. Compare:

- kongen bor i felsen → the king lives in the castle

- kongen bor i den fels som ligger i Rödby → the king lives in the castle which is located in Rödby

SÅDAN

- Sådan, sådant, sådanne (such/this/that kind) often refers to something which is mentioned or experienced earlier (an action, an object). Sådan must be in agreement with the noun’s gender and number:

- sådan en bok är kyfa → such a book is expensive

- sådant råd är unbrukalig → that kind of advice is useless

- sådanne perfekta skor → such perfect shoes

SAMMA

- Samma (same) is used to indicate something identical related to to context in question. Samma is not conjugated, it occurs in only one form.

- vir kom samma dag → we came the same day

- vir kommer samma dags → we come [on] the same days

SJÖLV

- Sjölv (self) is an indeclinable demonstrative which function is to emphasize nouns or pronouns. Its English counterparts are self/myself/yourself etc.

- Þi har gjorð deð sjölv → you (plural) have done it yourself

- ger deð sjölv (GDS) → do it yourself; DIY

EGEN

- Egen (own) is a demonstrative which function is to emphasize possession of nouns. Its English counterparts are own. It agrees with the noun’s gender and number.

- Egen has a slightly different usage than in English. Where in English one might say “do you have your own home?” in Femmish you would say «har þu[4] eð egeð hus?» or literally “do you have an own house?”:

- min egen hår → my own hair

- mið egeð hus → my own house

- mina egna katter → my own cats

BÅDE…OG

- Både…og (both…and) connects two or more units of any kind. Både is placed before the first part, and og before the second:

- eg möger både kafé og thé → I like both coffee and tea

- eg möger både kafé, thé og fruktsaft → I like coffee, tea and fruit-juice

DEMBÅDE

- Dembåde (both of them) refers to two persons or two concrete objects, that are countable items.

- eg möð dembåde idag → I met them both today

- dembåde var läcker → both (of them) were delicious

BÅDE ARTER

- Både arter (both kinds) relates to uncountable objects (mass nouns), general concepts or actions.

- kva är allerbäst; kafé eller thé? → what is the best of all; coffee or tea?

- eg möger både arter → I like both (kinds)

- kva är allerbäst; kafé eller thé? → what is the best of all; coffee or tea?

VERBS

- Verbs are words that name what is going on (actions, states of being, what exists). Femmish verbs occur in several forms as a result of conjugation. Femmish verbs are not conjugated in person and number. They inflect for the present tense, past tense, imperative, subjunctive, and indicative mode.

- Other tenses are formed by combinations of auxiliary verbs with infinitives or the past-participle. In total there are six spoken active-voice forms for each verb: infinitive, imperative, present, preterite/past and past participle. Verbs may also take the passive voice. Femmish uses the passive voice more frequently than English. The different forms of a verb can be divided into

- Finite forms, that is forms that express time (past, present) or mode.

- Infinite forms, that is forms that do not express time or mode.

- As in English you will find both regular (weak) and irregular (strong) verbs.

- Regular verbs form preterite (past tense) by adding a suffix to the stem.

- Irregular verbs form preterite without adding a suffix to the stem.

THE INFINITIVE

- The infinitive (dictionary form) of any verb in Femmish is given with the particle att → att vara (to be). When stating a verb without its particle, it is referred to as a bare infinitive. The infinitive form is the base form of the verb. This form is used together with auxiliary verbs to make complex verb forms. With auxiliary verbs the infinitive marker att (to) is not used.

- att möga → to like

- eg möger att mala → I like to paint

- eg kan mala → I can paint

CONJUGATING VERBS

- The stem of a verb is based on the present tense of the verb. If the present tense ends in -er, the -er is removed: tjener → tjen—. For short verbs, the -r is removed from the present tense of the verb, e.g., syr → sy—.

THE PRESENT TENSE

- Verbs do not inflect for person or number in Femmish. Therefore with all regular verbs, the present tense ending is either -ar or -er for all persons. Monosyllabic verbs such as att gå (to go) simply add -r in the present tense. Irregular verbs and modals generally have to be learned as there are no specific rules governing their conjugation.

- eg malar → I paint

- þu malar → you paint

- vir malar → we paint

- eg går → I go

- Note that Femmish verbs in the present tense do not conjugate differently to show continuity as they do in English (you paint vs. you are painting). However, Femmish does have a construction similar to English that conveys this meaning using the verb att vara and the infintive of a verb.

- de är att baka → they are (in the act of) baking

- eg är att gå → I am (in the process of) going

- Present tense forms of verbs may also be used in statements related to the future, quite often in connection with time phrases that are referring to the future:

- de kommer imorgon → they are coming tomorrow

THE PRESENT PARTICIPLE

- The present participle form is the adjectival form of the verb, and is used only as adjective or adverb, not as verb.

- In Femmish, the present participle is formed by adding -ande to the stem of verbs which end in unstressed -a in the infinitive, or -ende in those which do not. This form never changes regardless of gender or number:

- dansande gentor → dancing girls

- eð ökande antall → an increasing amount

- en gåttde båt → a going boat

FORMING THE NEGATIVE

- In Femmish, the negative is stated by placing the word inte behind the verb in question:

- eg malar inte → I don’t paint

- de är inte att baka → they are not (in the process of) baking

- A so-called negative infinitive can be formed by placing inte before a bare-infinitive. This form is often on signs and notices as a polite or formal imperative:

- inte mala → to not paint

- inte vara → to not be

- att vara, eller inte vara → to be, or not to be

- att vara, eller att vara ej[5] → to be, or not to be

- INTE AVKRUPPA PÅ VEGKANTEN! → no dumping on the roadside!

THE PRETERITE TENSE

- The preterite (also known as the simple past or aorist) expresses actions that took place or were completed in the past. The focus is on the action itself.

- Weak verbs are those which do not have sound-changes in their stem and instead attach endings to form the preterite. Weak verbs form the past tense with -de, -te, or -ðe depending on the preceding sound:

- The preterite ending will be -te if the stem of the verbs ends in -p, -t, -k or -s. For example, att häta (to be called) has as its stem hät-, and as -t is an unvoiced consonant, the past tense ends in -te, making hätte.

- The preterite ending will be -de if the stem of the verbs has a long vowel and ends in -d. For example, att småda (to slander) has as its stem småd-, and as -d is a voiced consonant, the past tense ends in -de, making smådde.

- The preterite ending will be -de if the stem of the verbs ends in -l, -m or -n. For example, att skemma (to damage) has as its stem skemm- so the past tense ends in -de, making skemmde.

- If the stem already ends in -dd or -tt, no extra -d or -t will be added.

- If the stem of the verb already ends in two different consonants such as -kn, -bn, -nd, -ld, -lt, -sk, -st or -rt, as in att starta (to start), the past tense retains the -a of the infinitive ending making startaðe the past tense.

- If the stem ends in -v as in att häva (to ferment) or -j as in att läja (to loan) the past tense ends in -ðe making hävðe and läjðe.

- If the infinitive ends in a vowel, e.g. att bo (to reside), the past tense is formed with just -ð e.g. boð[6].

- Strong verbs have sound changes in their stem which looks different in the preterite than in the present tense.

- eg får (I get) ' → eg fik (I got) '

- þu faller' (you’re falling) ' → þu föll (you fell)

- deð fryser (it’s freezing) ' → deð frös (it froze) '

- eg får (I get) ' → eg fik (I got) '

THE PRESENT PERFECT TENSE

- The present perfect tense, as in English, expresses actions that took place or were completed in the past and are no longer going on.

- “I have eaten breakfast”, indicates that breakfast is now eaten, and I have moved on to something else. Im Femmish this is constructed using the present-tense of the verb att ha (to have) and the past participle of the verb, sometimes known as the supine which is formed thus:

- If the stem of the verb contains a long vowel, as in att mala (to paint), its past participle is formed by adding -að making malað. However if the stem of the verb contains a long vowel and ends in -s, as in att visa (to show), its past participle is formed by adding -t making vist.

- If the stem of the verb already ends in two consonants such as -kn, -bn, -nd, -ld, -lt, -sk, -st or -rt, as in att verka (to work), the past participle is formed by adding -að making verkað.

- Verbs with stems which end in a consonant+t, as in att avkorta (to abbreviate) have a past participle formed by adding -að making avkortað.

- Verbs with stems which end in a doubled-consonant such as -ll, -mm or -nn, for example att förheffa (to elevate) have a past participle formed by removing one of the consonants and adding -t making förheft. If a verb already ends in -tt as in att retta (to direct), then so does its past-participle: rett. If a verb ends in -dd as in att redda (to rescue), then its past-participle becomes: redt.

- Verbs with stems which end in -v or -j have a past participle formed by adding -d: att leva (to live) becomes levd and att läja (to rent) becomes läjd.

- If the infinitive ends in a long vowel as in att bo (to reside), the past participle adds -tt to become bott. (Note that the -o is still pronounced as // in this case).

- If the infinitive ends in -na as in att öppna (to open) or att dregna (to trawl), the past participle adds -að to become öppnað and dregnað accordingly.

- Strong verbs often have irregular past participles which just have to be learned individually: e.g. att möda (to meet) → mött; att dycka (to dive) → duckað; att äta (to eat) → ätað.

- Unlike German or Dutch, the word order in the perfect tense follows the same pattern as English.

- eg har ätað görten → I have eaten the chicken

- þi har sett mig → you (polite) have seen me

- en segelbåt har avgått → a sailing-boat has departed

THE PRETERITE PERFECT (PLUPERFECT) TENSE

- The preterite perfect tense, as in English, expresses actions that had already taken place or were completed in the past. I had eaten breakfast, indicates that breakfast was already eaten prior to the narrative. Im Femmish this is constructed using the preterite of the verb att ha (to have) → hað; and the past participle (or supine form) of the verb. Again, unlike German or Dutch, the word order in the preterite perfect follows the same pattern as English.

- eg hað ätað görten → I had eaten the chicken

- þi hað sett mig → you (all) had seen me

- en segelbåt hað avgått → a sailing-boat had departed

AUXILIARY VERBS

- att vara (to be), att ha (to have), att få (to get), and att bliva (to become) are the most useful auxiliary verbs. As in most languages, all these verbs are irregular:

MODAL VERBS

- Modal, or auxillary verbs, are used extensively in Femmish in place of various verb moods used in other languages. For example, to express the conditional and the optative. Modal verbs are also used to construct the future tenses which are not conjugated. There are five modal verbs in Femmish:

- att skulla' → skal[9] ' → skulðe → *[10]skullað → shall/should

- eg ska komma → I shall come

- både skulðe ha redan avgått → both (of them) should have already left

- att villa → vil → vilðe → *villað → would

- eg vilðe möga att vara här → I would like to be here

- att måtta → må → måð → måen → to have to

- flaskor må inte kastes! → bottles must not be thrown!

- deð måð ske → that had to happen

- deð ha måen ske → that has had to happen

- att burda → bör → burðe → *burdað → ought/should (denotes obligation)

- eg bör sova → I ought to sleep

- þu burðe inte komma → You ought not have come

- att kunna → kan → kunðe → *kunnað → to be able to

- eg kan bila tysk → I can speak German

- eg kunðe inte komma → I could not come

- att skulla' → skal[9] ' → skulðe → *[10]skullað → shall/should

THE FUTURE TENSES

PRESENT FUTURE

- The future may be expressed in several ways. It is quite common to combine present tense of one of the modal auxiliaries att villa → vil or att skulla → skal (usually ska, at least in spoken Femmish) with infinitive of the main verb. Skal is used when the subject has a plan or purpose whereas vil often expresses an element of will or wish.

- eg ska gå i skolan → I will/shall go to school

- eg vil gå i skolan → I will/want to go to school

- The present future may also be expressed simply with the present tense in many cases:

- ikvöld, kommer eg rett frå skolan → tonight I will come straight from school

PRETERITE FUTURE

- This tense is expressing an action that was planned or went on in the past, but after another action. It is formed by preterite of att skulla → skulðe and the infinitive of the main verb:

- eg skulðe gå i skolan þa de kom → I was about to go school when they came

PRESENT FUTURE PERFECT

- This tense is expressing an action that has to be concluded before a certain time in the future. It is formed by present tense of an auxiliary verb + infinitive of att ha + past participle of the main verb.

- eg bör ha gått i skolan för kurseð startaðe → I ought to have gone to school before the course started

PRETERITE FUTURE PERFECT

- This tense is expressing an action that should have been concluded in the past (but was not) or an action that (doubtfully) will be concluded in the future. It is formed by preterite of an auxiliary verb + infinitive of att ha + past participle of the main verb.

- eg skulðe ha gått i skolan för kurseð startaðe → I should have gone to school before the course started

THE MIDDLE VOICE

- The middle voice is a verb form in Femmish that is easily distinguished by its -st endings. In principle, the middle voice is formed by adding -st to the infinitive or conjugated verb forms, as appropriate.

- The middle voice is used to express the following:

- Reflexivity The middle voice can replace a reflexive pronoun, as in, for instance, the following

- By the use of the middle voice verb form in Femmish, an idiomatic reciprocal action may be expressed:

- att mödas (to be met) → vir mödast (we meet each other)

- att vaskas (to be washed) → vir vaskast (we wash each other)

- vir vaskaðest (we washed each other)

THE PASSIVE VOICE

- The middle voice of a verb is used when the action is directed back on the subject rather than on the object. The classic English example: the dog ate the cat is in the active voice but becomes the cat was eaten by the dog when switched into the passive. The passive voice in Femmish is formed in one of four ways:

- By adding -ast to the stem of the verb → stärker (strengthens) becomes stärkast (is strengthened)

- this can even be given as a form of infinitive → att stärkast (to be strengthened)

- The passive is, however, more often formed using a form of att bliva (to become) + the past participle or using a form of att vara (to be) + the past participle:

- deð ble stärkað (it is strengthened)

- ble stärkað! (become strengthened!)

- deð är stärkað (it is strengthened)

- vära stärkað! (be strengthened!)

- Another form of the passive voice is analogous to the English get-passive. This form is used when you want to use a subject other than the normal one in a passive clause. In English you could say “the door was painted for him”, but if you want “he” to be the subject you need to say “he got the door painted”. Femmish uses the same structure using a form of att få (to get) + the past participle :

- han fik deð stärkað (he got it strengthened)

- eg får deð reparerað (I will get it repaired)

- The first form, using the middle voice tends to focus on the action itself rather than the result of it. The second (bliva-passive') stresses the change caused by the action. The third (vara-passive) puts the result of the action in the centre of interest:

- dören malast → the door is being painted (in the process of being painted)

- dören ble malað → the door is being painted (becomes painted), in a new color or wasn’t painted before

- dören är malað → the door is painted

- han fik dören malað → he got the door painted (by someone else)

- Passive impersonals may be formed my putting active personal verbs into the middle voice, as for example:

- att bruka (to use) → att brukast (to be used) → deð brukast (it is used; it is customary)

- att kväda (to say) → att kvädast (to be said)

- deð kvädast att idag är þorsdag (it is said that today is Thursday)

- att se ut (to seem) → att sest ut (to be *seemed)

- deð sest ut att idag är þorsday (it seems that today is Thursday)

- The passive may also be used to express idiomatic phrases:

- kvar finnast mödeð? → where is the meeting? or more literally: where is the meeting found?

- deð sägast att þetta hus är hemsökt → it is said that this house is haunted

THE IMPERATIVE MOOD

- The imperative, which is the form used to give orders, directions and instructions, is most often formed from the stem of the verb; but for many verbs it is the infinitive form. There are a few exceptions, notably vära! (be!):

- att spela → spela bollen! → play the ball!

- att följa → följ den näxta väjen! → follow the next road!

- att sköta → sköt pistoleð! → shoot the pistol!

- att vara → vära gott! → be good!

- att öppna → öppna dören! → open the door!

- Monosyllabic verbs which end in -e, -å or -u in the infinitive, are the same the imperative (although if there is an affixed preposition, it may be separated in the imperative):

- att få → få bollen! → get the ball!

- att utgi → utgi og fördömast! → publish, and be damned!

- An older, mostly obsolete subjunctive mood, formed by adding -e to the stem of the verb, is used idiomatically to refer to actions or states which are hypothetical or anticipated rather than actual, including wishes:

- The negative imperative, like in the present tense, is stated by placing the word inte (not) behind the verb in question:

- spela inte! → don’t play!

- få inte bollen! → don’t get the ball!

- följ inte den näxta vegen! → don’t follow the next road!

- parkér inte här! → don’t park here!

- As mentioned previously, a so-called negative infinitive can also be used on signs and notices as a more polite or formal imperative:

- INTE AVKRUPPA PÅ VEGKANTEN! → no dumping on the roadside!

- INTE LÅSA AV ÞENNA DÖR! → no locking this door!

NOMINAL MORPHOLOGY

GENDER

- There are two noun classes in Femmish: Common and Neuter. At some point in history, the older Masculine and Feminine genders merged to form the common.

- Gender is generally arbitrary and you have to learn which gender a noun is, but there are some rules to help you: natural gender (male/female) usually corresponds to the common gender.

- Some word-types always correspond to a certain gender; the -je diminutive ending always corresponds to common nouns: eð hus → en husje (a house → a cottage) even if the original noun was of neuter gender.

- The common nouns use the en indefinite article and the neuter ones use eð. They are often informally called n-words and ð-words as a result.

THE DEFINITE ARTICLE

- As in other Scandinavian languages, Femmish uses a clitic definite article, which means the word for the is joined to the noun it refers to rather than stands before it. The definite article agrees with gender and number. For common nouns it is -en and for neuter nouns it is -ið in the singular[13].

- man → mannen (the man)

- hus → husið (the house)

- kvenna → kvennan (the woman)

- merje → merjen (the maid)

- However, when an adjective precedes the noun, the definite article circumfixes the noun. Femmish exhibits what is known as double-article placement, that is, both the definite article and the clitic article are used:

- den glada kvennan → the happy woman

- deð sköna husið → the pretty house

- When an adjective precedes the definite plural noun, the definite article þe prefixes the noun-phrase:

- þe glada kvennorne → the happy women

- þe glada merjene → the happy maids

- þe stora husene → the big houses

- þe traveliga spillarne → the busy actors

Cultural note

- Femmish uses the definite article in places where English does not always use it. For example in street names, hospitals and governmental offices: Rådhusgatan (Townhall Street), Stadssjughuseð (City Hospital), and Skattmindigheten (The Tax Authority).

- Femmish also uses the definite article with abstract nouns: döðen (death), naturen (nature) and manniskeheten (humanity), in situations where English does not.

- döðen är en unvelkommen gast → death is an unwelcome guest

- skogar är en avdeling av naturen → forests are a part of nature

- eð ekträ är naturens värg → an oak tree is nature’s guardian

THE INDEFINITE ARTICLE

- Femmish uses an indefinite article in the same way English uses a/an. The indefinite article also agrees with gender. However, unlike the definite article, the indefinite article stands before the noun it refers to. For common nouns it is en and for neuter nouns it is eð. As in English, there is no plural indefinite article, the notion of some is handled by a separate pronoun.

- en kvenna → a woman

- eð merje → a maid

- Femmish does not use the indefinite article when talking about professions, religious/political affiliation, nationality, or medical conditions:

- han är fräðare → he is [a] student

- hon är katolik → she is [a] Catholic

- eg är engelsman → I am [an] Englishman

- eg har hoevond → I’ve [a] headache

PLURAL FORMS

- Nouns form the plural in a variety of ways. It is customary to classify Femmish nouns into five declensions based on their plural indefinite endings: -or, -ar, -er, -n, and unchanging nouns. Nouns with short vowels in their final syllable double the final consonant before adding the plural marker.

FIRST DECLENSION

- Nouns of the first declension are all of the common gender. The majority of these nouns end in -a in the singular and replace it with -or in the indefinite plural and -orne in the definite plural. For example:

- en kvenna (a woman) → kvennor (women)

- blomma (a flower) → blommor (flowers)

- kirkja (a church) → kirkjor (churches)

- A few nouns of the first declension end in a consonant, such as:

- en våg (a wave) → vågor (waves)

SECOND DECLENSION

- Nouns of the second declension are also of the common gender. This declension include common nouns ending in -e (or -é in French borrowings), -dom, -ing, -el, -en and -er. This declension also includes many monosyllabic nouns ending in a consonant. They all have the indefinite plural ending -ar and definite plural -arne. Examples include:

- en arm (an arm) → armar (arms)

- en hund (a dog) → hundar (dogs)

- en kloster (a cloister) → klostrar (cloisters)

- Second declension nouns which ends in -el, -en or -er in the singular, often syncopate the -e- in the definite form as well as in the plural:

- en äsel (a donkey) → äslar (donkeys)

- viken (vetch) → viknar (vetches)

- vinter (winter) → vintrar (winters)

- Two second declension nouns modify their root-vowel in the plural:

- moder (mother) → mödrar (mothers)

- dotter (daughter) → döttrar (daughters)

THIRD DECLENSION

- The third declension includes both common and neuter nouns. This declension include common nouns ending in -ad, -an, -d, -t, -st, -het, -else, and -and. This declension include neuter nouns ending in -eum and -ium which are derived from Latin[14]; the polysllabic neuter nouns ending in -eri and a great number of monosyllable nouns of each gender with various endings.

- The indefinite plural ending for nouns of this declension is -er or for nouns ending in -e, it is simply -r. For definite plural nouns of this declension the ending is -erne or -rne. For example:

- en fjand (an enemy) → fjander (enemies)

- eð museum (a museum) → museer (museums)[15]

- museið (the museum) → museerne (the museums)

- eð bageri (a bakery) → bagerier (bakeries)

- en skrivelse (a writ) → skrivelser (writs)

- Third declension nouns ending in -and and -ång change -a- and -å- into -ä- in the plural:

- en hand (a hand) → händer (hands)

- en tand (a tooth) → tänder (teeth)

- en tång (a tong) → tänger (tongs)

- A handful of third declension nouns modify their root-vowel but do not double their final consonant in the plural:

- en natt (a night) → nätter (nights)

- en stad (a city) → städer (cities)

- en fader (a father) → fäder (fathers)

- Third declension monosyllabic nouns change -o- into -ö- and many double their final consonant in the plural:

- en bok (a book) → böcker (books)

- en ordbok (a dictionary) → ordböcker (dictionaries)

- en ros (a rose) → röser (roses)

- en fot (a foot) → fötter (feet)

- en jarðnöt (a peanut) → jarðnötter (peanuts)

FOURTH DECLENSION

- All nouns in the fourth declension are of the neuter gender and end in a vowel in the singular. Their plural ending is -n. For definite plural nouns of this declension the ending is -ene or -ne. For example:

- eð äpple (an apple) → äpplen (apples)

- eð ög (an eye) → ögen (eyes)

- eð öre (an ear) → ören (ears)

FIFTH DECLENSION

- Fifth declension nouns include common nouns ending in -are and -ande and all neuter nouns ending in a consonant[16] which are invariable in the plural (except for neuter nouns containing -a- which become -ö- in the plural). The definite plural marker of fifth declension nouns is -ene or -ne:

- en bagare (a baker) → bagare (bakers)

- eð ärv (an inheritance) → ärv (inheritances)

- eð bär (a berry) → bär (berries)

- eð barn (a child) → börn (children)

- eð land (a country) → lönd (countries)

THE GENITIVE CASE

- The genitive case is marked simply by adding -s to a noun. Unlike in English, it is never marked by an apostrophe-s. Femmish uses the genitive case to denote possession:

- Jans skor → Jan’s shoes

- However, note that with body parts, and family relations, the words are inverted by convention and nouns are always given in the definite form:

- hoen Jans → Jan’s head and not Jans hoen

- modren Jans → Jan’s mother and not Jans mor

- To preserve euphony, sometimes -es is added to a noun which ends in -st, -sk or -sp:

- en fiskes ögen → a fish’s eyes

- en väspes brodd → a wasp’s stinger

- The genitive case can also be marked by using av (of) as in English:

- skorne av Jan → Jan’s shoes (the shoes of Jan)

- modren av Jan → Jan’s mother (the mother of Jan)

- The genitive case, when it refers to proper nouns, buildings or events being of or from a certain place, can also be marked by ved (at):

- Köbmannen ved Veneti → The Merchant of Venice

- Turnið ved London → The Tower of London

- den stora pyramiden ved Giza → The Great Pyramid of Giza

- Slagið ved Hastings → The Battle of Hastings

- The genitive case is also used adverbially in idiomatic expressions:

- with days of the week or months of the year to translate temporal idioms:

- mandags, kommer eg hemma → [on] Mondays, I come home

- arbetar þu onsdags? → do you work [on] Wednesdays?

- junis, har han urlop → he has vacation [every] July

- and with certain set phrases which denote a locative sense:

- han dog till steds! → he died on the spot!

- hemma, sover eg på decken → at home I sleep on the floor

- with days of the week or months of the year to translate temporal idioms:

ADJECTIVES

- An adjective modifies a noun or a pronoun by describing, identifying, or quantifying words. An adjective usually precedes the noun or the pronoun which it modifies.

- An adjective can be modified by an adverb, or by a phrase or clause functioning as an adverb.

- Adjectives can come either within nominal phrases (for example, “a large dog”) or in the predicate (for example, “the dog is large”).

ATTRIBUTIVE ADJECTIVES

- Attributive adjectives which stand alone with their noun or with the definite article do not inflect for gender in Femmish. Instead, they always take the so-called weak ending, -a:

- den nya banahoven → the new railway station

- deð nya svalskåpið → the new refrigerator

- þe nya skolorne → the new schools

- privata skolor→ private schools

- Attributive adjectives retain their unmodified form when they stand between the indefinite article (en|eð) and the nouns which they qualify:

- en goð merje → a good maid

- en goð kvenna → a good woman

- eð ny hus → a new house

- en privat skola → a private school

PREDICATE ADJECTIVES

- Adjectives used predicatively always display gender agreement with a singular subject. It does not matter whether the subject is definite or indefinite. Common gender nouns take the -a ending while neuter nouns take the -t ending:

- kvennan är mjuka → the woman is meek

- en kvenna är mjuka → a woman is meek

- skåbið är tomt → the cupboard is empty

- eð skåb är tomt → a cupboard is empty

- Adjectives used predicatively with a plural subject are always unmodified regardless of the gender of the subject. It does not matter whether the subject is definite or indefinite:

- kvennorne är mjuk → the women are meek

- kvennor är mjuk → women are meek

- skåbene är tom → the cupboards are empty

- skåb är tom → cupboards are empty

- When an adjective ends in -ng, -nk, -rk ,-rm or -rt, it is suffixed by -et with neuter nouns:

- ädikið ble starket → the vinegar becomes strong

- vannið är varmet → the water is warm

- barnið är unget → the child is young

- skåbið är snurtet → the wardrobe is tidy

- The neuter -t is never added to adjectives which end in -sta or -st, including all superlatives:

- barnið är äldasta → the child is the eldest

- wienerbrödeð är törfrust → the Danish pastry is freeze-dried

- It should be noted that the neuter -t is not added to predicate adjectives of nationality:

- klavrið är fjämsk → “the piano is Femmish” and not klavrið är fjämskt

- kvädið var japansk → “the poem was Japanese” and not kvädið var japanskt

ADJECTIVES USED WITH UNCOUNTABLE NOUNS

- If you’re describing an uncountable noun, that is, a noun which cannot be pluralized such as mjölk (milk) or vann (water) within a nominal phrase, the adjective is conjugated based on the gender of the noun it describes:

- kalda mjölk → cold milk

- varmeð vann → warm water

EXCEPTIONS AND NOTES ON ADJECTIVES

- Predicate adjectives which follow a verb without a noun, or adjectives given alone, are always assumed to be neuter:

- goð (good) → vära gott! → be good!

- skön (pretty) → virkeligt skönt! → really pretty!

- In most cases, an adjective which ends in a double consonant loses one before -t is added in the neuter.

- sann (true) →

- deð sanna levakostið → the true cost of living

- sagafräðið var sant → history was true

- nass (wet; soft) →

- deð nassa lakridsið → the soft licorice

- lakridsið är nast → the licorice is soft

- sann (true) →

- When a predicate adjective ends in a long vowel, it is suffixed by -a with common nouns and -tt with neuter nouns and is unmodified in the plural:

- ny → nya → nytt → ny

- flaggen är nya → the flag is new

- deð stora husið var nytt → the large house was new

- þe kvida strompor är ny → the white socks are new

- blå → blåa → blått → blå

- flaggen är blåa → the flag is blue

- deð stora husið var blått → the large house was blue

- þe nya strompor är blå → the new socks are blue

- ny → nya → nytt → ny

- Some adjectives are indeclinable and some do not take the so-called weak ending, -a. For example, the adjective fager (fair) does not change at all and the adjective goð (good) never takes an -a in the singular:

- den fager mädjen → the fair girl; and not → den fagra mädjen

- mädjen är fager' → the girl is ' fair; and not → mädjen är fagra

- den goð savonen → the good soap; and not → den goða savonen

- savonen är goð → the soap is good; and not → savonen är goða

ADJECTIVES FORMED FROM PAST-PARTCIPLES

- Adjectives can be formed from the past-participle of verbs, much in the same way that other Germanic languages do it. However, it must be noted that the past-participle undergoes a change when used as an adjective:

- viglað (“enclosed”; from att vigla) → viglaða; viglett; viglaða

- meldren såg den viglaða bilden → the messenger saw the enclosed picture

- brevið var viglett → the letter was enclosed

- eg har viglaða brevene → I have the enclosed letters

- belagrað (“beseiged”; from att belagra) → belagraða; belagrett; belagraða

- mannen såg den belagraða felsen → the man saw the beseiged castle

- fyrhusið blev belagrett → the lighthouse was beseiged

- hjären anföll belagraða byar → the army attacked beseiged towns

- viglað (“enclosed”; from att vigla) → viglaða; viglett; viglaða

ADJECTIVES IN THE NEGATIVE

- In Femmish, many adjectives have distinct opposite pairs for positive/negative adjectives but some adjectives can often be made negative simply by prefixing them with un- (as in English or German):

- normal (normal) → unnormal (abnormal)

- jävn (even; level) → unjävn (uneven; unlevel)

- siv (pure) → unsiv (impure)

SYNCOPE IN ADJECTIVES

- When a multi-syllable adjective ends in -er, -en, -el etc. the unstressed final -e- is usually syncopated before adding -a with common nouns and plurals, and -ett with neuter nouns and also with comparitive/superlative adjectives:

- vågen → vågna → vågnett → vågna

- donker → donkrare → donkrasta

NOMINAL ADJECTIVES

- Adjectives can be used without a qualifying noun when used nominally. In English one can say “the blue [ones]” without giving the noun and in Femmish you can do something similar by treating the adjective as if it was followed by a neuter gender noun:

- deð blåa → the blue (one)

- eg vil gärna ha deð blåa → I will gladly have the blue (one)

- eð blå → a blue (one)

- eg vil gärna ha eð blåa → I will gladly have a blue (one)

- þe blåa → the blue (ones)

- eg förväljer att ha þe blåa → I prefer to have the blue (ones)

- deð blåa → the blue (one)

- Past-participles of verbs, with the same modification as shown above, can also be used as nominal adjectives as follows:

- þe fördömaða → the condemned/damned (ones)

- ingen kan hjälpa þe fördömaða → nobody can help the condemned (ones)

- þe besvigaða → the deceived (ones)

- jödene var þe besvigaða → the Jews were the deceived (ones)

- þe fördömaða → the condemned/damned (ones)

POSSESSIVE ADJECTIVES

- When possessive pronouns act like adjectives, they act like indefinite articles and so take unmarked adjectives:

- mina goð kvennor → my good women

- derra ny bilar → their new cars

- vort ny hus → our new house

ADJECTIVAL NUMERALS

- When a numeral precedes an adjective or a counter, the numeral is treated as if it were an indeclinable adjective:

- þe tvålv mjuka kvennorne → the twelve meek women

- þe syv stora husene → the seven large houses

- förti gamla hus → forty old houses

- en måss goða män → a few good men

COMPARISONS & SUPERLATIVES

- To form comparitives, that is to say something is as big, as good, as fast as something else, the construction uses så...som with adjectives or adverbs:

- eg geð så drugt som mögligt (I went as slowly as possible)

- kom så snart som þu kan! (come as soon as you’re able!)

- hon var så stor som en kval! (she was as big as a whale!)

- One of the most typical features of adjectives is gradability. An adjective is gradable if it can express comparison, e.g. bigger, better, faster than something else. To form a gradable adjective, one simply adds -are to the existing adjective regardless of gender or number.

- den älda herren (the old gentleman) → den äldare herren (the older gentleman)

- den sköna frun (the pretty woman) → den skönare frun (the prettier woman)

- deð höga stäkið (the tall ladder) → deð högare stäkið (the taller ladder)

- han blev nervösare og nervösare (he became more and more nervous)

- To say something is the biggest, best, fastest, etc., one simply adds -(a[17])st to the adjective regardless of gender or number.

- den älda herren (the old gentleman) → den äldasta herren (the oldest gentleman)

- den sköna frun (the pretty woman) → den skönsta frun (the prettiest woman)

- deð höga stäkið (the tall ladder) → deð högsta stäkið (the tallest ladder)

- There are exceptions to these rules where separate, irregular forms of comparison and superlatives exist.

- den goð mannen (the good man) → den bädra mannen (the better man) → den bäst mannen (the best man)

- den unga frun (the young woman) → den yngra frun (the younger woman) → den yngsta frun (the youngest woman)

- deð liteð husið (the small house) → deð mindra husið (the smaller house) → deð mindsta husið (the smallest house)

- As in English, you can also use mer (more) and mest (most) with unmodified adjectives to create comparitives and superlatives:

- deð mer mager svinið (the more lean pig) → deð mest mager svinið (the ¨ pig)

- den mer skön frun (the more prettier woman) → den mest skön frun (the most pretty woman)

- deð mer hög stäkið (the more tall ladder) → deð mest hög stäkið (the most tall ladder)

- This form is imperative with adjectives derived from verbal participles:

- nuvarande (present/current)

- deð mer nuvarande dagbladið (the more recent newspaper)

- deð mest nuvarande dagbladið (the most recent newspaper)

- nuvarande (present/current)

- The superlative can be emphasized and enforced by use of aller- (of all), or by use of -mest (-most), which does not inflect:

- deð allergrönsta träið → the greenest tree of all

- deð västmest fyrhusið → the westernmost lighthouse

- deð allermindsta husið → the smallest house of all

- den bortmest grensen → the outermost boundary

- When you compare two objects, X and Y, and X is bigger than Y, you can express the relationship by using änd - than:

- X är storare änd Y → X is bigger than Y

- hon var storare änd en kval! → she was bigger than a whale!

ADVERBS

- Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, verb phrases or sentences. They describe circumstances related to the action (how, when, where, to which degree). They report how likely it is that the action reported occurred, and they report the speaker’s attitude to what is being said.

- They may be of two kinds: native adverbs which are indeclinable words and adjectival adverbs which are formed by putting the adjective in neuter singular form: snäll (quick) → snält (quickly)

- eg körar snält → I am running quickly

- komm snält! → come quickly!

- Adjectives ending in -lig may take either the neuter singular ending -t or the suffix -en, and occasionally -ligen is added to an adjective not already ending in -lig:

- stor (large/great) → storligen (greatly)

- årlig (annual) → årligen (annually)

- den älda herren kommer här årligen → the elderly gentleman comes here annually

- vir saknar hem storligen → we miss him greatly

WORD ORDER AFTER ADVERBS

- When an adverb fronts a phrase (usually to place focus or emphasis on the adverb), the usual SV word-order becomes VS:

- eg kom snält körande! → I came quickly running!

- snält, kom eg körande! → quickly, I came running!

MODIFYING ADVERBS

- Adverbs of degree are qualifying other adverbs, adjectives or quantifiers. These adverbs are placed in front of the word they modify. They cause the adjective to become unmodified:

- Göran är liteð þrött → Göran is a little tired

- Göran är gäligt þrött → Göran is extremely tired

ADVERBS OF PLACE

- Adverbs of direction in Femmish show a distinction that is lacking in English: some have different forms depending on whether one is heading that way, or already there. For example:

- eg steg upp på täkið → I climbed up on the roof (from down below)

- eg arbetaðe dort uppå täkið → I was working up there on the roof (but I was already up there)

- han travðe inn på eldhusið → he strode into the kitchen (from another room)

- han travðe rond inne eldhusið → he was striding about in the kitchen (already being in there)

PREPOSITIONAL ADVERBS

- Some prepositions in Femmish have the effect of making the noun with which they are combined take a final -e when the compound word is used adverbially. For example:

- döð (death) → tilldöðe → until death

- liv (life) → innlive → alive; in life

BARA

- A wish or hope can sometimes be expressed by using the adverb bara and the subjunctive mood to introduce a sentence with the meaning “if only...”, “as long as...”, “I hope that...”:

- bara deð regne ej! → as long as it doesn’t rain!

- bara þu blive inte sjuk! → you’d better not become ill!

- bara þu biðe! → just you wait!

POINTS OF THE COMPASS

- The points of the compass in Femmish are: östið, västið, norðið and suðið and they are used in phrases like öst för (to the east of), väst för (to the west of), etc. and við norðið (in the north), við suðið (in the south), etc. mot norðið (towards the north), mot suðið (towards the south), etc.

- Adding -lig turns them into adverbs of direction: suðlig (southern), östlig (eastern), etc. Additionally, adding -ligen gives the added meaning of movement in that direction: suðligen (towards the south/in a southerly manner), östligen (easterly/towards the east), etc. These examples might be heard when describing winds in a weather forecast, for example, or in phrases such as: gå västligen! → go west!

- Compounds with frå gives the notion of origin: norðfrå (from the north), suðfrå (from the south), etc.

- han är norðfrå → he is northern (ie from the north)

- han är norðfråman → he is (a) northerner (ie a man from the north)

- en västfrå vind → a westerly wind (ie a wind blowing from the west)

- The additional points of the compass in Femmish are simple compounds: norðöstið, norðvästið, suðöstið and suðvästið.

- Adding -lig turns them into adverbs of direction: suðöstlig (southeastern), norðöstlig (northeastern), etc. Additionally, adding -ligen again gives the added meaning of movement in that direction: suðöstligen (towards the southeast/in a southeasterly manner).

- When giving directions to an even greater degree of accuracy, one can say suð-suðöstligen (towards the south-southeast — SSE) etc.

NUMBERS

COUNTING

- In Femmish, numbers are counted in base-ten, or decimal, the same way they are in English or German. In fact, the numbers 1 through 20 are almost the same as their English or German counterparts.

- The number one is declined depending on whether the noun is common or neuter gender; however when counting in general, en is used as the cardinal number.

- Numbers above one are considered indeclinable in Femmish: cardinal numbers are treated as common nouns, and ordinal numbers are treated as indeclinable adjectives.

- 0 null zero / 1 en/eð one / 2 två two / 3 tre three / 4 fir four / 5 fem five / 6 sex six / 7 syv seven / 8 ått eight / 9 negen nine / 10 tju ten / 11 elleve eleven / 12 tvålv twelve / 13 tretten thirteen / 14 fjörten fourteen / 15 femten fifteen / 16 sexten sixteen / 17 sytten seventeen / 18 åtten eighteen / 19 negenten nineteen / 20 tvånti twenty / 21 tvåntien twenty one / 30 tretti thirty / 40 förti forty / 50 femti fifty / 60 sexti sixty / 70 sytti seventy / 80 åtti eighty / 90 negenti ninety / 100 hundrað hundred

- 1a första first / 2a andra second / 3e trede third / 4e fjörde fourth / 5e femde fifth / 6e sexte sixth / 7e syvde seventh / 8e åtte eighth / 9e negende ninth / 10e tjunde tenth / 11e ellevde eleventh / 12e tvålvde twelfth

- en penning → one penny; två penningar → two pennies.

- eð särk → one shirt; fem särk → five shirts.

- tre, två, en, gå! → three, two, one, go!

- Note that the -ten in numbers such as fjörten is pronounced [-ti:n] and the -ti in higher units is pronounced as [-ti:]

- fjörten [fjɶrti:n]

- förti [fɶrti:]

NUMBER CONVENTIONS

- As in most of Europe, large numbers are separated with a dot (period) rather than a comma as is the custom in English-speaking countries. Conversely, the comma is used to mark decimal fractions.

- 1,000,000 (one million) → 1.000.000

- 3.147 → 3,147

NUMBER EXPRESSIONS

- Some phrases in Femmish involving numbers are idiomatic or so-called set phrases which must be learned as-is.

- þe kom av tvåor → they came in twos / they came two by two

- ägg kommer av tvålvor → eggs come by the dozen

- en firdel[18] → a quarter; a fourth part

- en femmje → a fiver; either a Ð5,00 bill or a five on a playing-card

DOING ARITHMETIC IN FEMMISH

- When doing simple addition, one uses the word på (on) where English would say plus:

- kva är två på elleve? → what is two plus eleven?

- When doing simple subtractions, one uses the word minus (minus) as one does in English:

- kva är elleve minus två? → what is eleven minus two?

- When doing simple multiplication, one uses the word mal (times) as one does in English:

- kva är två mal två? → what is two times two?

- When doing simple division, one uses the word delað av (divided by) as one does in English:

- kva är tju delað av fem? → what is ten divided by five?

QUANTITIES AND MEASURES IN FEMMISH

- Femland is, like most of Europe, a metric nation but in the more rural areas one might still find produce which is sold in older measures. Note that unlike English, the of is not translated when giving a quantity of something.

- en liter bensin → a liter of gasoline

- en skäffel äpplen → a bushel of apples

- eð uns smör → an ounce of butter

- en thélebbel mjöd → a teaspoon of honey

TELLING THE TIME IN FEMMISH

- Traditionally, as in England, the twelve hour clock is used in everyday conversation. If one needs to clarify whether morning or afternoon is being talked about, one can add the idiomatic expression morgons, eftermiddags to mean morning or afternoon, and kvölds or natts to mean in the evening or at night.

- Afternoon is usually considered to run from noon until 6pm and then it is evening from 6pm until 9pm and then until about 3am it is usually considered to be night.

- kva är klocken? → what time is it?

- hur sent är deð? → how late is it?

- klocken är negen → it’s nine o’clock

- klocken är negen morgons → it’s nine o’clock in the morning

- klocken är halv negen → it’s half-past eight o’clock[19]

- klocken är tju över negen → it’s ten past nine o’clock

- klocken är tju över negen kvölds → it’s ten past nine o’clock in the evening

- klocken är fem på tvånti för negen → it’s twenty-five before nine o’clock

- klocken är middag → it’s noon

- klocken är midnatt → it’s midnight

- við klocken negen, kommer vir → at nine o’clock, we’re coming

READING THE DATE IN FEMMISH

- Dates in Femmish are read DD/MM/YYYY, that is to say, the date is given first, then the month and then the year. This is the same way that most of Europe handles dates.

- The days of the week are: mandag', tirsdag, onsdag, þorsdag, fredag, lördag and söndag. ' They are considered common nouns and are not given capital letters as they are in English.

- The months of the year are: januari, februari, mart, april, maj, juni, juli, august, september, oktober, november, desember. They are also considered common nouns and are not given capital letters as they are in English.

- mandag, den 1. april 2013 → Monday, the 1st April 2013

- eg reser till Rödby den 1. juni → I will travel to Rödby on the 1st June

- When talking about in what year something happened, Femmish uses no preposition:

- årið 1066 kom Normänene till England → in the year 1066 the Normans came to England

DERIVATIONAL MORPHOLOGY

- Derivation is the process of forming a new word on the basis of an existing word, as in the English happiness and unhappy from happy, or determination from determine. It often involves the addition of a morpheme in the form of an affix, such as -ness, un- and -ation in the preceding examples. Femmish is rich in derived words and will often favor a word built on existing Femmish roots rather than use an internationalism.

DERIVING NOUNS

ABSTRACT NOUNS

- Femmish forms abstract nouns a number of ways the most common being with the suffix -het which corresponds roughly to the English -ness. All nouns in this class are considered common gender regardless of the gender of the noun they were derived from. Nouns of this class can also be formed from adjectives.

- dove (deaf) → dovehet (deafness)

- mödig (proud) → mödighet (pride)

NOUNS FROM VERBS

- Femmish forms nouns from verbs in various ways but one of the most productive methods is with the suffix -ing or -ning. There is no difference between these two endings but some verbs favor one over the other and the correct form just has to be learned. (Verb stems which end in -v always use the -ning form). All nouns in this class are considered common gender.

- att översätte (to translate) → översätting (translation)

- att rette (to direct; to point) → rettning (direction; heading)

- Another way to create nouns from verbs is with the suffix -else. All nouns in this class are considered common gender.

- att begrabe (to bury) → begrabelse (burial)

- att beväge (to move) → bevägelse (movement)

PERSONAL OR AGENTIVE NOUNS FROM VERBS

- By far the most common derivation for agentive nouns, especially for those derived from professions or occupations, are the endings -are and -ör which are derived from verbs or nouns. Some agentive nouns are simply different words though (see engineer below).

- As in English and German, it is possible to find agentive nouns ending in -man (man) or -fru (woman) and increasingly, names of professions or occupations that were once the sole domain of men are now being used in the feminine as well. Additionally, some agentive nouns which are inherently masculine, may have a feminine counterpart ending with either -ska or -inna.

- sömmare (seamster) → sömmarska (seamstress)

- hushållare (janitor; custodian) → hushållarska (housekeeper)

- kunst (art; craft) → kunstare (artist; craftsman)

- verkfräð (engineering) → ingeniör (engineer)

- kongen (the king) → konginnan (the queen)

- hus+fru (house woman) → husfru (housewife)

- köb+man (buying man) → köbman (merchant)

- Femmish also has agentive nouns ending in -ist which usually denotes a person who is an adherant or follower of a philosophy, religion or political system; but is also used for some generic professional agents.

- kommunisme (communism) → kommunist (communist)

- kontor (office; bureau) → kontorist (clerk; official)

LOCATIVE NOUNS

- Locative nouns are those which denote the location in which an activity takes place. In Femmish, the most productive derivation for this type is the ending -erei which corresponds to the English -ery. This ending causes locative nouns to also be considered neuter. Added either to a verb, or to an agentive noun, this ending denotes that the new noun refers to where the agent carries out his trade or activity (and in some cases, the trade itself):

- brygge (to brew; make beer) → bryggeri (brewery)

- skrädder (tailor) → skrädderi (tailor’s shop)

- snedkare (carpenter) → snedkeri (carpenter’s workshop but also carpentry itself)

- Other nouns can compound to form what are essentially locative nouns. The word verk (work — in the singular) can compound to form the meaning of works, factory or workshop:

- järn (iron) → järnverk (iron-works; shipyard etc.)

- bil (car) → autoverk (autoworks; garage; workshop etc.)

AUGMENTATIVE NOUNS FROM OTHER NOUNS

- Femmish does not have a productive derivation to denote augmentative nouns but may compound existing nouns using stor- (large; great):

- en by (a town) → en storby (a city; large town)

- en markað (a market) → stormarkaðen (the supermarket)

DIMINUTIVE NOUNS FROM OTHER NOUNS

- The most productive derivation to form diminutive nouns from other nouns is the -je diminutive ending which always corresponds to common nouns:

- These nouns usually have some form of “cute” or “affectionate” connotation associated with them rather than just denoting a reduction in physical size. This ending may also cause sound-changes in the original noun, essentially creating new words.

- eð hus (a house) → en husje (a cottage); even if the original noun was of neuter gender: en katt → en kattje (a cat → a kitty); en hund (a dog) → en hundje (a doggy).

- Other diminutive nouns can be formed by adding små- (small) to an existing noun. This does not change the gender of the underlying noun:

- barnið (the child) → småbarnið (the toddler) → småbörnene (the toddlers)

- småbarnskobnen → the toddler’s play-pen

- varor (goods; merchandise) → småvaror (haberdashery; “smalls”)

- ungfru Else hað en småvarorsbuð i Rödby → Miss Else had a haberdashery shop in Rödby

- fjär (money; cash) → småfjär (change; pocket-change)

- har þu småfjär för en femmje? → do you have change for a five?

- barnið (the child) → småbarnið (the toddler) → småbörnene (the toddlers)

- Diminutive nouns can also be formed by adding -ling to an existing noun. Often nouns of this type are offspring or derivations of whatever the original noun was. All nouns in this class are common, even if the underlying noun was neuter:

- en hund (a dog) → en hundling (a puppy; whelp)

- eð trä (a tree) → en träling (a sapling)

- eð får (a sheep) → en fårling (a lamb)

- Some nouns in this category do not have an inherent diminutive meaning but are merely derived from a noun implying something larger or more important:

- en ädling (a prince) ← ädel (noble; aristocratic)

INSTRUMENTAL NOUNS FROM VERBS

- In Femmish, instrumental nouns are essentially treated as though they were agentive nouns, as it is seen that the tool or device is the agent of the action. Therefore the endings -are and -ör are most commonly employed to this end.

- att krosta (to crush; pulverise) → en steynkrostare (a rock-crusher)

- att beskydda (to protect; cover) → en bokbeskyddör (a book-cover; dust jacket)

NONSENSE NOUNS, OR SO-CALLED -IS WORDS

- In parallel to the English style of putting -thingy on a noun to form a vague, nonsensical noun; Femmish does something similar by adding -is to a root, forming a neuter gender uncountable noun used informally and in speech.

- goð (good) → goðis (candy; sweets; goodies)

- goðisið var unförbiðaðt → the present was unexpected

- þing (thing; object) → eð þingis (a thingamajig; gizmo)

- mannen gerðe eð þingis → the man made a gizmo

- goð (good) → goðis (candy; sweets; goodies)

DERIVING VERBS

INCHOATIVE VERBS