Wistanian

Wistanian [əˈniɡəˌlilɑn] | |

| Spoken in: | Wistania |

| Conworld: | Vale |

| Total Speakers: | ~ 50,000,000 |

| Genealogical classification: | Taliv - Taliv-Nati Pidgin - Wistanian |

| Basic word order: | Verb-Subject-Object |

| Morphological Type: | Analytical |

| Morphosyntactic Alignment: | Nominative-Accusative |

| Created by: | |

| Paul A. Daly | Began: January 2017 Published: January 2018 |

| Further Resources | |

| Wistanian Lexicon (WIP) | r/wistanian on Reddit |

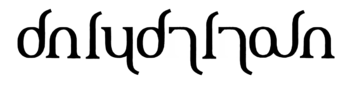

Wistanian (IPA: /wɪsˈteɪni.ən/), natively known as anigalilaun (IPA: /əˈniɡəˌlilɑn/), is the first constructed language (conlang) by world-builder, writer, and professional amateur Paul A. Daly, written in 2017 and 2018. The language was created for a novel series. The first novel is near completion, but will likely remain unpublished until the author finishes his education.

The language is spoken on the fictional planet Vale, on a large yet isolated island called Wistania. The language belongs to the Talivian sub-family, which evolved steadily throughout the Taliv's existence. After having been settled on by the Taliv for several hundred years, the island became the new home for the Bwolotil people, who had fled to the island to hide a large collection of magical and extremely dangerous ajmastones. The Bwolitil were originally apathetic toward the Taliv until they discovered that the Taliv held one such ajmastone as a central symbol of their culture. The Bwolotil, therefore, engaged in war with the Taliv to apprehend their ajmastone. Three separate people groups also inhabited the island during this war, one of which was the Nati people who allied with the Taliv to win the war. This alliance led to the formation of the Taliv-Nati pidgin, which was later named anigalilaun, meaning "the language of peace". During the events of the novel series (about 300 years after the end of the war) Wistanian is the majority language of the island. The language also has a number of influences from the Katapu (sister peoples to the Nati and known for their religious traditionalism), the Uzin (a people distantly related to the Bwolotil who settled the island shortly after the beginning of the war), and the Bwolotil.

Wistanian is typologically an analytic language with very small elements of agglutination. Its grammar is initially simple to grasp, lacking noun gender and case, and possessing few verbal conjugations, although most of its difficulty is syntactic and lexical. Despite having a rather regular morphology due to pidginization, there are several groups of words within the same lexical category which operate differently from each other. Wistanian is primarily written using the Talivian Alphabet, but some alternate scripts do exist, namely the Diwa Alphabet and Nati Abugida.

Introduction

Setting

Wistanian is spoken on the fictional island nation of Wistania. The language stems from a pidgin created between the Nati and Taliv languages during The Wistanian War. After the peace treaty was signed, the Katapu, who were allied with Nati and Taliv but inactive in the war, documented and refined the Nati-Taliv Pidgin for use in the newly established government. Wistanian features mostly Taliv grammar, Nati vocabulary, Katapu influences, many Bwolotil loan words, and scientific terms, mathematics, and the lunar calendar derived from the work of the Uzin. Wistanian's native name, anigalilaun, is a compound of ani (language) and galilaun (peace). It is translated literally as "Peace Language."

The five different people groups of Wistania remained isolated from each other for part of the post-war era. However, trade and intermarriage became more commonplace, requiring a competent lingua franca. This is followed by religious evangelism by the Katapu, engineering from the Uzin, and entertainment from the Nati, all of which Wistanian was the primary language for distribution and promotion. Eventually, the language became taught as a mandatory subject in school. After only a couple centuries, Wistanian advanced from a government-only auxiliary language into the national language of the island, natively and fluently spoken by most of its citizens.

As a result, Wistanian is mostly regular, with a moderately small phonological inventory and vast dialectal variation. It is the most spoken and embraced by the Taliv and Nati people groups, and the least spoken by the Bwolotil people group, who often protest the language's difficulty. The other five languages are still spoken, especially the Bwolotil language which still has a number of monolingual non-Wistanian speakers. Both the Uzin and Katapu have important texts written in their languages, while Taliv and Nati have shifted into archaism, although they are still taught in school.

Goals

Wistanian was created with three goals in mind:

- To be naturalistic, yet unique. It should have its own unique phonology, grammar, and lexicon, not identical to any natural language on earth, but still naturalistic and sensible.

- To represent the Wistanian culture. This language was designed for songs and speeches, bedtime stories and battle cries, gentle wisdom and fierce ambition, hope and struggle. This language is designed for the Wistanians: their personality, their history, and their heart.

- To be novel-friendly. Crazy letters and long words will confuse and alienate most readers, which is why Wistanian was designed to have short, easily readable words that readers can enjoy, one small sentence at a time.

Inspiration

Like most first conlangs, Wistanian started as an English relex (but without tense and articles). However, after nearly six mass revisions over two years, Wistanian has become its own unique language. It's influenced by several languages, especially Spanish and Tamil, but their influence is mostly found in the lexicon while contributing only minimally to the grammar.

Phonology

Inventory

Consonants

The consonants are as follows (allophones are in [brackets]):

| Labial | Alveolar1 | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | [ŋ]2 | |||

| Stop | voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||

| unvoiced | p | t | k | |||

| Fricative | v | z | ʒ | [ɣ]3 | ɦ | |

| Liquid | w ~ βʷ4 | ɾ ~ r5 | j | |||

| Lateral | l | |||||

- Alveolars (except /ɾ ~ r/) are pronounced laminally.

- n > ŋ / _[velar]

- ɦ > ɣ / #_, [stress]_

- /w/ is spoken in emphasized or slow speech, while /βʷ/ is spoken in quick speech. Whenever immediately following a consonant, this is always pronounced as /w/. In the Western Dialect, it is always pronounced as /w/.

- /r/ is spoken in emphasized or slow speech, while /ɾ/ is spoken in quick speech. In some words, the trilled is preferred even in quick speech; for example, ggarauni (large) is almost always pronounced [kəˈrɑni].

Vowels

The vowels are as follows (allophones in [brackets]):

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i [ɪ]1 | ɯ [u]2 | |

| Mid | e | [ə]1 | |

| Low | a | ɑ [ɒ]2 | |

| Diphthong: ai̯ | |||

- All vowels lengthen when stressed.

- All vowels become breathy after /ɦ/.

- /i/ and /a/ shift to [ɪ] and [ə] whenever unstressed. The only exception is when /i/ follows /j/, /w/, or /l/ or is at the end of a word.

- /ɯ/ and /ɑ/ shift to [u] and [ɒ] after /w~βʷ/.

Phonotactics

Syllable Structure

Wistanian has a (C/FA)V(N) syllable structure where C represents any consonant, F represents any fricative, A represents /j/ or /w/, V represents any vowel, and N represents any consonant that is not /j/, /w/, or /ɦ/.

Syllable onsets may be any consonant or any fricative followed by /j/ or /w/:

- m, n, p, b, t, d, k, ɡ, v, vj, vw, z, zj, zw, ʒ, ʒj, ʒw, ɦ, ɦj, ɦw, w, r, j, l.

Syllable nuclei may be any vowel:

- i, e, a, ɑ, ɯ, ai̯

Syllable coda may be any consonant that is not /j/, /w/, or /ɦ/.

- m, n, p, t, k, b, d, ɡ, v, z, ʒ, ɾ, l

Stress

Stress usually falls on the first non-lax vowel (/ai̯/, /i/, /e/, /a/, /ɯ/, or /ɑ/). But there are many exceptions, especially where the vowels /i/ and /a/ come into place since you must know whether or not those sounds are the stressed /i/ or /a/ or the lax [ɪ] or [ə]. A prime example is between the words viman and viman, which are spelled identically. When stress is on the /i/ as in [ˈvimən], the word means “sugar”, but when stress is on the /a/ as in [vɪˈman], the word means “sky.” /ai̯/ and /e/ are always stressed. /ɯ/ is always stressed unless it's word-initial (in which case it will usually shift to [ʊ]). /ɑ/ is usually stressed unless non-lax /a/ or /i/ are present. Secondary stress is also lexical, but rare. Many particles and common monosyllabic words are not stressed unless the feature the /e/ or /ai̯/ vowels. (E.g.,va is normally [və], and zi is normally [zɪ]; but aa is normally [ˈe].)

Stress is realized through vowel lengthening and sometimes a higher intonation.

Prosody

In Wistanian culture, speaking loudly is considered rude. Therefore, Wistanian language is typically spoken softly and clearly. It is arguably a stress-timed language that realizes stressed syllables and stressed words by lengthening vowel duration.

Orthography

Romanization

Wistanian employs its own script, but it is romanized with a system that reflects the script and its spellings. The romanization rules are as follows:

- /m/, /n/, /b/, /d/, /ɡ/, /v/, /z/, and /l/ are represented with the corresponding IPA symbol.

- /p/, /t/, and /k/ are represented by ⟨bb⟩, ⟨dd⟩, and ⟨gg⟩, respectively.

- /ʒ/, /ɦ/, /ɾ~r/, /w~βʷ/ and /j/ are represented by ⟨j⟩, ⟨h⟩, ⟨r⟩, ⟨w⟩, and ⟨y⟩, respectively.

- /ɯ/ and [u] are represented by ⟨u⟩.

- /a/ and [ə] are represented by ⟨a⟩.

- /i/ and [ɪ] are represented by ⟨i⟩.

- /ai̯/ is represented by ⟨ai⟩.

- /e/ is represented by ⟨aa⟩.

- /ɑ/ and [ɒ] is represetned by ⟨au⟩.

Wistanian employs a number of peculiar digraphs: ⟨bb⟩ = /p/, ⟨dd⟩ = /t/, ⟨gg⟩ = /k/, ⟨aa⟩ = /e/, and ⟨au⟩ = /ɑ/, .

When Wistanian writing was developed, /p t k/ only existed allophonically, and /e, ɑ/ did not exist at all. Therefore, glyphs were not made for those sounds. As the language changed and came into contact with other languages, /p t k/ became distinct sounds. Rather than making new glyphs, spellers decided to double up ⟨b⟩, ⟨d⟩, and ⟨g⟩. /e/ is only present in loan words, and the emergence of /ɑ/ is not yet decided, although it's likely due to some conditional /a/ shifting and substrate influence. Since there are only three vowel glyphs, they combined ⟨a⟩ with ⟨u⟩ to represent /ɑ/ as ⟨au⟩, doubled up ⟨a⟩ to represent /e/ as ⟨aa⟩, and kept ⟨ai⟩ as the digraph for the language's only diphthong, /ai/. ⟨ii, ia, iu, ui, ua, uu⟩ are respelled as ⟨yi, ya, yu, wi, wa, wu⟩.

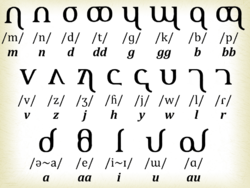

Script

Wistanian has an alphabet which represents the different sounds in Wistanian. The alphabet was inspired by Latin, IPA, and Greek, but is often described as Armenian-looking. The font, based on Cambria, was created using Autodesk Sketchbook for the iPad and converted into a font using Calligraphr and TypeLight.

The script, often referred to as araman taliv auzanigza (lit. "dishes of the Taliv") began its evolution during the Diwa oppression when the Taliv people were secretly plotting escape by setting their dishes outside their homes in certain orders to convey messages. After their escape and resettlement on the Wistanian island, the dishes gave form to the written language.

Another interesting feature of the script is "compound glyphs." They are /k/, /t/, /p/, /e/, and /ɑ/, and they are made by doubling or combining two different glyphs together. This is why the romanization of Wistanian uses ⟨gg⟩ for /k/, ⟨au⟩ for /ɑ/, as well as the other digraphs.

Like the lexicon and grammar, Daly redesigned the Wistanian script multiple times - three, to be exact. The original script was an alphabet, but it did not capture the "spirit" of Wistanian, so it was scrapped for an abugida. The abugida, which was beautiful, was also difficult to learn and write, prompting yet another redesign. The original design is now considered as the old Diwa alphabet, while the abugida is an alternative script used by the Nati.

Dialectal Variation

Wistanian has three main dialects: Standard (Central), Western, and Northern.

The Standard dialect is explained as above and is required to be spoken by all government officials, messengers, and professional educators. This dialect is influenced heavily by the Taliv and Nati languages, and as a result is spoken predominately and naturally by those two people groups in addition to the Uzin in the northwest. However, some variation is still present, primarily in regards to word-final plosive dropping (e.g. alaudd (tall, high) [əˈlɑt] > [əˈlɑ]), a habit present in most children and domestic laborers. Uzin speakers have a similar shift, {p t k} > [ʔ] / _#, including a > æ and j > ʎ / V_V. Regardless, this is only considered a "variation" of the Standard Dialect that government officials and messengers ought to train against.

The Western Dialect, spoken predominately by the Bwolotil, has several distinguishing factors, specifically the complete rounding of /ɯ ɑ/ to /u ɒ/ and the rounding of /i e/ to /y ø/ after /w/. Schwas are commonly dropped in between consonants, and /n/ is dropped before /ɡ k/. This dialect also has several lexical differences, such as different kinship terms, specialized vocabulary, unique figures of speech, and the lack of honorifics. This dialect also features a formal register, spoken among Bwolotil strangers, where VSO word order is replaced with SOV word order.

The Northern Dialect, spoken by many Katapu, is primarily distinguished through extensive devoicing in both fricatives and plosives so that words such as vigaz /viɡaz/ are pronounced [fikas]. Standard /p t k/ are ejectivized as /p' t' k'/. This dialect also tends to put nasals and voiced plosives as interchangeable so that ani could be pronounced as [ani] or [adi]. Vowels also undergo a number of shifts, such as ɯ, ɑ > ʊ, o. Like the Western Dialect, the Northern dialect features different kinship terms, specialized vocabulary, unique figures of speech, and a formal register. In contrast, the Katapu has a large collection of honorifics which are based on age, sex, and occupation.

Syntax

needs expansion

Wistanian follows a fairly rigid syntax and tight grammar for a number of historical reasons. Firstly, due to its pidginization with the Nati language, Taliv lost most of its irregularities and exceptions. Secondly, as the Katapu began to teach Wistanian, they had spread false information to "make more sense" of the language, which resulted in further simplification that was later adopted as standard. In Wistanian's infancy, it was almost engineered to be as efficient as possible. However, learners were still able to incorporate features from their native language into Wistanian, providing it with several of its current syntactical quirks (e.g., imperative word order was introduced by the Taliv learners).

Lexical Categories

Wistanian has five traditional lexical categories (parts of speech): the noun (davagg), the verb (anai), the modifier (yigbizaun), the particle (mauvaldul), and the honorofics (jili).

| Nouns | davagg | Any word that takes on nominal morphology and can act as a subject or object the verb. |

|---|---|---|

| Verbs | anai | Any word that takes on verbal morphology. |

| Modifiers | yigbizaun | Any word that describes or specifies another word. |

| Particles | mauvaldul | Any word that has a grammatical role and cannot take on any additional morphemes. |

| Honorifics | jili | A polite title used with many proper nouns. |

Some scholars argue that there are more parts of speech. For example,wi and igza are arguably more semantically fit to be postpositions. However, they are treated like modifiers morphologically, and therefore labeled as such. Relativizers va, na, ggaun, and ddal could possibly constitute their own part of speech since they do act slightly differently than most particles and carry both a semantic and grammatical meaning.

Nouns include colors, numbers, and possessive pronouns, therefore they are never treated as modifiers. In order to use them to modify a noun, one must use the relativizer particle va.

alalyi dari va din. alali-i dari va din. run -TEL boy COP.REL three. "The three boys ran (to something)."

Word Order

Wistanian has predominant Verb-Subject-Object word order, modifiers that follow their head, post-positional suffixes, and particles that come before their head. Modifier phrases will usually come at the beginning or end of the sentence.

azavyi ravu miram wi daz ilam aa naulam ggarauni va din ggaun maumu va zi. azavi-i ravu miram wi daz ilam aa naulam ggarauni va din ggaun maumu va zi. carry-TEL fast store ADE man young ACC melon large COP three BEN mother COP 3Sa.POSS. "The young man quickly carried large melons that are three to the store for his mother." *carried fast store to man young melons which.is three large for mother who.is his.

Questions

Questions will typically follow the same syntactic pattern as declarative sentences, except with rising intonation. All questions should end with the question particle a (Q). This is especially important in writing since the Talivian Alphabet does not have an equivalent to the question mark. However, some dialects and informal registers do not include it in speech. In speech, the question particle is typically stressed.

Polar

Typically, Yes/No questions will consist of a statement followed by zau/baun (Yes/No).

magin va raul, zau a? magin va raul, zau a? table COP red, yes Q? "Is the table red?” (Lit. "The table is red, yes?")

Non-Polar

Non-polar or content questions are formed using a "dangling particle" and rising intonation, inviting the listener to respond by completing the thought.

lu va a? lu va a? 2S.NOM COP Q? “Who are you?” (Lit. "You are...?")

yigai auzi aa a? yiga -i auzi aa a? speak-TEL 3Sa.NOM ACC Q. "What did he say?" (Lit. "He said...?")

ddaij yaun auv a? dda-i -j yaun auv a? go -TEL-IRR 1P.NOM when Q? "When will we go?" (Lit. "We will go when/during...?)

yi luj ddal a? yi luj ddal a? 1S.POSS boat LOC Q? "Where is my boat?" (Lit. "My boat is located in...?)

magin va raul, diri a? magin va raul, diri a? table COP red, why Q? “Why is the table red?” (Lit. "The table is red because...?")

Imperatives

In imperatives, word order changes to VOS. In polite requests, a speaker uses the irrealis mood conjugation on the main verb and includes a subject noun (usually an honorific). In rude demands, the speaker does not use the irrealis mood conjugation nor includes a subject noun.

vigaj aa garauda baul. viga-a -j aa garauda baul. eat -ATEL -IRR ACC food HON. "Please, eat the food, sir."

viga aa garauda. viga-a -∅ aa garauda ∅ eat -ATEL ACC food "Eat the food (as a rude demand)."

Location

Wistanian does not have a consistent way to express the location of an object or action; it instead uses a variety of methods and means to declare where something is taking place, including relativizers, modifiers, verbs, and compound nouns.

The most basic of the locative strategies is the locative relativizer itself, ddal. By using this relativizer to connect two ideas, a Wistanian speaker is saying that A is located in/on B.

garauda ddal magin. garauda ddal magin. food LOC table. "The food is on the table."

ujadi ggarauni ddal maliyan. ujadi ggarauni ddal maliya -n. house large LOC mountain-PL. "The large house is in the mountains."

To express nearness to an object (A is located near B), B is given the modifier wi (glosses as ADE for adessive), which follows its head. To express distance from an object (A is located far from B), B is given the modifier igza (glossed as DSTV for distantive), which also follows its head.

luj ddal garauvi wi. luj ddal garauvi wi. boat LOC water ADE. "The boat is near the water."

luj ddal garauvi igza. luj ddal garauvi igza. boat LOC water DSTV. "The boat is far away from the water."

To express that something is located above or below another object (A is located above/below B), B compounds with auzdda (head) to express above, and compounds with zanju (foot) to express below.

luj ddal garauvizanju. luj ddal garauvi-zanju. boat LOC water -foot. "The boat is underwater."

luj ddal garauvjauzdda. luj ddal garauvi-auzdda. boat LOC water -head.. "The boat is above the water."

These compounds can also be combined with wi or igza to emphasize how close or how far A is below/above B.

luj ddal garauvizanju igza. luj ddal garauvi-zanju igza. boat LOC water -foot DSTV. "The boat is far under the water" (implies that it's sunk to the bottom.)

Another method, which does not use the locative ddal, is the use of stative verbs, mainly vizaniya (come.STA meaning "to be within") and zwiliya (leave.STA, meaning "to be outside").

mala yaun gaun vizaniya aa ujadi. mala -a yaun gaun vizana-iya aa ujadi. fight-ATEL 1P.NOM ACT come -STA ACC house. "We fight inside the house." * "fight we who have come into the house"

yaun vizaniya aa ujadi. yaun vizana-iya aa ujadi. 1P.NOM come -STA ACC house. "We are in the house." * "We have come into the house."

Locative clauses do not modify verbs directly, but rather modify the subject. This includes sentences that use verbs like "go."

ddai yau ujadi wi. dda-i yau ujadi wi. go -TEL 1S.NOM house ADE. "I go to the house." * "go I house near."

nada lu luj igza. nada-a lu luj igza. walk-ATEL 2S.NOM boat DSTV. "You walk away from the boat." * "walk you boat away."

Morphology

Wistanian has a low morpheme-to-root ratio, most words being inflectionless and rather interacting with nearby words and word order to express grammatical (and sometimes lexical) distinctions.

Nouns

Wistanian nouns come in three classes: proper, improper, and pronouns. Proper nouns refer to names of people or places ("Wistania", "Alija"), while improper nouns refer to generic terms (e.g., "country", "man"), and pronouns refer to substitute words for other nouns and noun phrases. Proper nouns are never inflected, however, improper nouns can be inflected for the plural number, be compounded, or undergo derivational morphology to become a verb or modifier. Pronouns can take on more inflections than improper nouns.

Number

Wistanian has three grammatical numbers: singular, paucal, and plural. Proper nouns do not inflect for number at all, improper nouns only distinguish between paucal and plural, while pronouns only distinguish singular and plural. This unique distinction arose as a result of Middle Taliv, which had a singular/paucal/plural distinction, then merged the paucal and singular before it transitioned to New Taliv. The pronouns, however, maintained the singular/paucal/plural distinction, then later lost the paucal, resulting in a singular/plural distinction in pronouns.

All count nouns can be declined into the plural number with the suffix -(a)n. For improper nouns, they are not conjugated as plural if a) there is only one or a few of a thing, or b) it is modified with a number phrase.

Pronouns

Pronouns come in five persons: first, second, third animate, third inanimate, and third person spiritual. These four persons are split into three grammatical categories:

- Nominative (

NOM) Used as the subject of the sentence. - Accusative (

ACC) Used as the object of the sentence. - Possessive (

POSS) Used for possession.

1st Person

First person singular (1S) pronouns are used to refer to the speaker. First person plural (1P) is used to refer to the speaker and an indeterminate number of others.

| Nominative | Accusative | Possessive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | yau | dau | yi |

| Plural | yaun | daun | yin |

2nd Person

2nd person singular (2S) pronouns are used to refer to the listener/reader. 2nd person plural (2P) is used to refer to two or more listeners/readers.

| Nominative | Accusative | Possessive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | lu | liv | luhi |

| Plural | lun | livan | luhin |

3rd Person Animate

3rd person animate pronouns are used to refer to people and some animals, especially pets and birds. They come as both singular (3Sa) and plural (3Pa).

| Nominative | Accusative | Possessive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | auzi | auzi | zi |

| Plural | auzin | auzin | zin |

3rd Person Inanimate

3rd person inanimate pronouns are used to refer to wild animals, objects, events, noun clauses, and even entire sentences. They come as both singular (3Si) and plural (3Pi).

| Nominative | Accusative | Possessive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | vi | vai | vi |

| Plural | vin | vain | vin |

3rd Person Spiritual

3rd person animate pronouns are used to refer to spirits, sacred objects and places, and the dead. They come as both singular (3Ss) and plural (3Ps).

| Nominative | Accusative | Possessive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | ja | ja | ji |

| Plural | jan | jan | jin |

Verbs

Verbs only conjugate four lexical aspects. There is no tense, but it is rather expressed through context and other modifier phrases. Only the irrealis mood is conjugated to the verb, while other moods are expressed through modifiers and context. Verbs do not compound with any other part of speech.

Aspect

needs polishing

The Wistanian understanding of aspect is different than what one will find in most natural languages. Rather than conjugating for grammatical aspect, Wistanian conjugates for lexical aspect. In other words, the very definition of a verb may change based on its conjugation.

The four lexical aspects are: stative, durative, telic, and atelic.

- Stative verbs (

STA) describe a situation or action that is unchanging over a long period of time. Stative verbs do not describe temporary actions, but rather the result of a temporary action or a series of temporary actions that identify the subject. - Durative verbs (

DUR) are dynamic and indicate that an action is in progress from one state to another. - Telic verbs (

TEL) are dynamic and punctual, describing an action with an endpoint. More specifically, it refers to any action that has been completed as intended. In most situations, it strongly implies the past or future tense and the perfective grammatical aspect. - Atelic verbs (

ATEL) are dynamic and punctual, describing an action that does not have an intended endpoint. Like the telic, this aspect strongly implies the past or future tense, but is often grammatically imperfective.

ASPECT

/ \

STATIVE DYNAMIC

/ \

DURATIVE PUNCTUAL

/ \

TELIC ATELIC

For example, the verb bima means to "fall" in the telic, "precipitate" in the atelic, "descend" in the durative, and "to be fallen (i.e., lying on the ground after a fall)" in the stative. bima still expresses the same basic meaning — "the subject goes downward" — but its implications change based on its conjugations. This is also true of the verb ja, which means "like" in the stative, "fall in love" in the durative, "achieve or accomplish" in the telic, and "want" in the atelic. Again, the basic meaning remains — "the subject has a desire" — but the differing conjugations further explain what kind of desire is being had: an unchanging desire (stative), a growing desire (durative), a satisfied desire (telic), or an unsatisfied desire (atelic).

These aspects also imply certain grammatical features. Indeed, these aspects originally did refer to grammatical aspects a thousand years within Wistanian's history. The stative was once the gnomic aspect, the durative was once the continuous aspect, and the telic and atelic were once the perfective and imperfective aspects, respectively. This shift was slow, however, but it picked up mightily during the pidginization with the Nati, since lexical aspect could allow them to communicate using fewer verb roots, so words such to "to put on" were replaced with the durative conjugation for the stative "to wear".

Stative

Stative verbs (STA) describe a situation or action that is unchanging over a long period of time. Stative verbs do not describe temporary actions, but rather the result of a temporary action or a series of temporary actions that identify the subject. For example, consider the following sentence:

yigiya yau anigalilaun. yiga -iya yau ani -galilaun speak-STA 1S.NOM language-peace. "I speak Wistanian." / "I am a speaker of Wistanian"

The verb in the above sentence informs the listener (or reader) that the subject, the speaker, speaks Wistanian, and does so homogenously and for a long period of time. It is a series of temporary action that identifies the subject; i.e., it can easily be translated into "I am a speaker of Wistanian." A more dynamic conjugation would likely infer that the speaker is only speaking temporarily.

This can also refer to something called the resultative, which applies to verbs that do not inherently express a stative act. For example, bima (discussed in the section above) describes the motion from a high place to a low place. This involves movement and change, which the stative conjugation does not mess with. Instead, bima in the stative means "to be fallen (i.e., lying on the ground after a fall)". Lying on the ground is a stative action, which is also a result of a previous non-stative action. Another example for this is the verb dula, "to put on, clothe", which, in the stative, translates as "to wear" (or in a more roundabout way: "to have put on").

Stative verbs are conjugated as such (apostophes indicate stress):

| REGULAR | STATIVE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|---|

| 'viga | vi'giya | to be eaten, destroyed completely |

| 'zani | za'niya | to be loud, rude |

| 'hadu | ha'diya | to know |

Durative

The durative aspect (DUR) is a dynamic aspect which indicates that an action is in progress from one state to another. Consider the following sentence:

yiga yau anigalilaun. yiga -a yau ani -galilaun. speak-DUR 1S.NOM language-peace. "I am speaking Wistanian."

This sentence informs the listener that the speaker is in the process of speaking Wistanian. Unlike in the stative example, which simply indicated that the speaker knows and has the ability to speak Wistanian, the durative is indicating that the speaker is actually speaking it at the present moment. This aspect strongly implies the verb is present and imperfect, grammatically, although context could give more precise details.

Durative verbs specifically describe the process of going from one state to the other, usually opposite, state. For example, yiga in the durative describe the process from the beginning of a statement to the end of a statement. The word ja, which means "falling in love" in the durative, describes the process from a state of apathy to a state of obsession. This is especially notable in the following example of hadu. In the stative, it means "to know", but in the durative, it describes the process from being ignorant to being informed: "to learn."

Durative verbs are conjugated as such (apostophes indicate stress):

| REGULAR | DURATIVE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|---|

| 'viga | 'viga | to be eating |

| 'zani | 'zana | to be shouting, rude |

| 'hadu | 'hada | to be learning |

Telic

The Telic Aspect (TEL) is a dynamic, punctual aspect which describes an action with an endpoint. More specifically, it refers to any action that has been completed as intended. In most situations, it strongly implies the past or future tense.

yigai yau luv. yiga -i yau luv. speak-TEL 1S.NOM 2S.ACC "I told you."

In this sentence, the same word for "speak" is used, but its lexical analysis has changed, at least in an obvious way for English speakers. The English verb "tell" has an intended goal and an endpoint. Whereas, in Wistanian, all that is required is the telic conjugation on the word for "speak".

Unlike the durative aspect, the Telic is used on verbs that have been completed, rather than verbs that are in the process of being completed. This is why Telic verbs are rarely in the present tense since things occurring in the present are usually still unfinished. Returning to our example of ja, the telic conjugation defines the desire as fulfilled and satisfied ("to accomplish"), while the durative describes a desire that is unsatisfied and still growing ("falling in love"). As for bima, which describes the action of going from a high place to a low place, both can technically be translated as "fall" or "descend", however the telic bima demands that the subject has actually hit the floor and finished its fall, while the durative demands that the subject is still in that process.

Telic verbs are conjugated as such (apostophes indicate stress):

| REGULAR | TELIC | DEFINTION |

|---|---|---|

| 'viga | vi'gai | to eat |

| 'zani | 'zanyi | to shout (esp. insult) |

| 'hadu | 'hadwi | to figure out, discover |

Atelic

The Atelic Aspect (ATEL) is a dynamic, punctual aspect that describes an action that does not have an intended endpoint. Like the telic, this aspect strongly implies the past or future tense.

yiga yau luv. yiga -a yau luv. speak-TEL 1S.NOM 2S.ACC. "I talked to you."

For English speakers, this sentence will get very fuzzy. In the atelic conjugation, yiga, which refers to the act of letting words come out of your mouth, has no intended endpoint. This points to a conversation, in which case the subject is conversing with the object. However, unlike in English, the preposition "to" or "with" is unnecessary because of the atelic conjugation. Whereas "tell" is more directive, implying an exact message for an exact person or group, "talk" is more open, implying that any subject is being spoken about to any number people.

This is very clearly seen with the word bima, which is defined as "fall" in the telic, but "precipitate" in the atelic. The reason for this very specific translation is that falling rain does not have an intended endpoint — it just rains for the sake of raining. A single drop of rain, however, does have an endpoint — landing on the ground. As a result, the atelic bima only applies to weather, mass nouns, and ideas such as hope or peace when they are "coming down" upon a person or group of people.

Sometimes, the telic and atelic verbs can have identical translations into English, as is the case for buda, which translates to "to walk" in both the telic and atelic aspects. The difference between these two verbs is that telic walking has an intended endpoint — "I walked to the store" — whereas atelic walking does not — "I walked in circles."

Atelic verbs are conjugated as such (apostophes indicate stress):

| REGULAR | ATELIC | DEFINITION |

|---|---|---|

| 'viga | 'viga | to chew, destroy |

| 'zani | 'zanya | to shout, insult |

| 'hadu | 'hadwa | to remember/recall |

NOTE: Durative and Atelic ⟨-a⟩ verbs have identical conjugations. However, context can easily make clear the two aspects. In almost every case, atelic verbs apply to a past or future action, while durative verbs apply to a present action.

Restrictions of Lexical Aspect

Before we dismiss the discussion about Wistanian lexical aspect, it's important to note a few things:

- Not every verb can undergo every conjugation. For example "to run" is never conjugated as stative, and "to laugh" is inherently atelic and would not fit as a telic, durative, or stative verb. Although most verbs will be able to make a lexical switch comfortably, there are many that don't.

- Not every lexical shift makes sense on the surface. The different shifts for ja do make sense because each situation describes a desire. Some verbs, such as buda, which translates as "to walk" in the telic, atelic, and durative, make a drastic change in the stative: "to be given a gift." This oddity arose historically; when messengers, who would spend entire days or week walking all over the country, would arrive at home. It was customary to be given a reward for their travels from their family (in most cases, that gift was flowers).

- Not every noun can be the object of every verb in every conjugation. For example, in the above example sentences, yiga in the stative and durative used the object of "Wistanian" while the telic and atelic examples used the object "you." This is because it is conceptually impossible for one to speak to Wistanian or to tell Wistanian something. Since there is a lexical shift, the nouns that are allowed as subjects and objects will not always remain the same. An interesting case is with the word bima. In the atelic conjugation, it is translated as "precipitate", which means that it can only be used with mass nouns such as "rain" and "wheat" (or emotions, figuratively) as the subject. Therefore, neither people nor clay pots can bima in the atelic.

Mood

Verbs are conjugated for the irrealis mood, which is used in polite requests, questions, and in conjunction with epistemic or deontic particles. This is done with the suffix ⟨-j⟩. Indicative negative verbs are not conjugated as irrealis.

| NOMINAL | VERBAL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STATIVE | DYNAMIC | |||||||

| DURATIVE | PUNCTUAL | |||||||

| TELIC | ATELIC | |||||||

| realis | irrealis | realis | irrealis | realis | irrealis | realis | irrealis | |

| viga | vigiya | vigiyaj | viga | vigaj | vigai | vigaij | viga | vigaj |

| zani | zaniya | zaniyaj | zana | zanaj | zanyi | zanyij | zanya | zanyaj |

| hadu | hadiya | hadiyaj | hada | hadaj | hadwi | hadwij | hadwa | hadwaj |

Modifiers

Modifiers immediately follow their head. Morphologically, there is no difference between an adjective and an adverb, since they rely on word order. Modifier phrases can be expressed either at the beginning or end of a sentence or after the verb, if it modifies it. Temporal phrases prefer the beginning of the sentence.

Negation

Nouns, verbs, and modifiers can be negated using the prefix bau(n)-.

baudaiziya yau. bau-daizi-iya yau. NEG-sing -STA 1S.NOM. "I do not sing."

haaggiya bauzaun aa audi va zi. haaggi-iya bau-zaun aa audi va zi. insult-STA NEG-person ACC grandfather COP 3Sa.POSS. "No one insults their grandfather."

luj id na baubi. luj id na bau-bi. boat PROX POSS NEG-good. "This boat is not good."

Particles

Particles in Wistanian are words which have a grammatical meaning rather than a semantic meaning. They also do not inflect. Particles always come before their head.

Object Particles

In Wistanian grammar, any noun that does not act as a subject is considered an object and are not exclusive to the patient of the verb. As an object, the noun comes after the subject and inherits an object particle (unless it is an accusative pronoun.)

The object particles are:

| Accusative | ACC

|

aa | Marks the patient of the sentence. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental | INS

|

il | Marks the means by which an action is done. |

| Benefactive | BEN

|

ggaun | Marks the reason for which something is done volitionally. |

| Causative | CAU

|

diri | Marks the reason for which something is done involitionally. |

It is possible to have a sentence that uses several objects, although none of them are required in a sentence. When multiple objects are present in a sentence, they are usually ordered in a sentence as ACC > INSTR > BEN/CAU.

ila yau aa ujadi il divu ggaun jyaman va yi. ila -a yau aa ujadi il divu ggaun jyam -an va yi. build-DUR 1S.NOM ACC house INS wood BEN child-PL COP 1S.POSS. "I am building a house with wood for my children."

Accusative

The accusative particle marks the patient of a transitive verb.

maniyai ami aa umbu va zi. mayiya-i ami aa umbu va zi. break -TEL friend ACC bone COP 3S.POSS "The friend broke their bone."

When the patient is a pronoun, the accusative particle is normally dropped, since some pronouns have their own accusative forms. The accusative can also double as a reflexive.

vigai dari vai. viga-i dari vai. eat -TEL boy 3Si.ACC. "The boy ate it."

yiga yau dau. yiga -a yau dau. speak.to-ATEL 1S.NOM 1S.ACC. "I speak to myself."

The accusative form of the third person animate and spiritual pronouns are identical to their nominative counterparts. The accusative particle is added if the patient is different than the agent, but is omitted if used as a reflexive.

dduwi auzi auzi ddu-(w)i auzi auzi. hit-TEL 3Sa.NOM 3Sa.ACC "He hit himself."

dduwi auzi aa auzi. ddu-(w)i auzi aa auzi. hit-TEL 3Sa.NOM ACC 3Sa.ACC. "He hit him."

After instrumental, benefactive, or causative particles, pronouns are still conjugated as accusatives.

gaun zariya dari vai. gaun zariya dari il vai. gaun zariya dari ggaun vai. gaun zariya dari diri vai. The boy plays it. The boy plays with it. The boy plays for it. The boy plays because of it.

Instrumental

The instrumental particle (INSTR) marks the instrument by which something has been done. For example, shooting with a bow, eating with a fork, and singing with a sore throat. In Wistanian, instrumental nouns are marked with the particle il.

gariya yau il guddi. gari-iya yau il guddi. work-STA 1S.NOM INSTR hammer. "I work with a hammer."

The instrumental particle is also used to mark the theme of a ditransitive verb, doubling as a sort of dative marker.

dazjyi yau liv il jauni. dazji-i yau liv il jauni. give-TEL 1S.NOM 2S.ACC INSTR flower. "I gave you a flower." (Lit. "I give you with a flower.")

The instrumental particle is used for emphatic reflexives by complimenting the accusative form of the subject pronoun.

rainaij yau aa duvij il dau. raina-i -j yau aa duvij il dau. dig -TEL-IRR 1S.NOM ACC hole INSTR 1S.ACC "I will dig the hole myself."

Benefactive and Causative

The benefactive and causative object particles perform similar functions, yet carry different connotations. Benefactives rely primarily on the reason for which something was done volitionally (i.e., on purpose), while causatives marked the reason something is done involitionally (i.e., not on purpose). These two particles are not exchangeable and they cannot both be present to compliment the same verb.

murwi auzi ggaun liv. muru-i auzi ggaun liv. die -TEL 3S.NOM BEN 2S.ACC. "He died for you." / "He died for your benefit."

murwi auzi diri liv. muru-i auzi diri liv. die -TEL 3S.NOM CAU 2S.ACC. "He died because of you." / "It was your fault he died."

In the above sentences, the benefactive particle tells us that the subject "he" willingly died or sacrificed his life for the object "you". The causative particle suggests that the subject "he" was killed, rather by accident or by premeditated murder, because of the existence or actions of the object "you".

The particle diri is the same word in the clause-initial construction diri va, which translates as "because" or "the reason is".

Modal Particles

needs polishing

These particles are featured before the verb and indicate verbal modality.

| Conditional | COND

|

a | Denotes "if" the verb will occur. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capable | CAP

|

yaj | Denotes that the subject "can" do something. |

| Hypothetical | HYP

|

zaggu | Denotes something that might happen, but does not. |

| Deontic | DEO

|

daaya | Denotes something that ought to happen. |

| Epistemic | EPIS

|

ibiz | Denotes something that might have happened. |

The conditional mood (COND) is used to form "if" clauses, such as "if she sings" and "if we go", etc. This is homonymous with the question particle, and they are often considered the same word. The verb head of the conditional particle is always conjugated for the irrealis mood.

a murwij ya, junaij lu ddal dim dau. a muru-i -j yau, juna-i -j lu ddal dim dau. COND die -TEL-IRR 1S.NOM, bury-TEL-IRR 2S.NOM LOC hill 1S.ACC. "If I die, you will bury me on the hill."

The capable mood (CAP) is used to form "can" verbs, such as "she can sing" and "we can go". It is often used as not only an indicator of ability, but also permissiveness. To denote incapability, the speaker will attach the negation prefix to the verb.

yaj iliya yau aa maliya. yaj ilu-iya yau aa maliya. CAP see-STA 1S.NOM ACC mountain. "I can see the mountains."

The hypothetical mood (HYP) denotes an action that could occur but doesn't, such as "I could go" or even "I could have gone". The verb head of a hypothetical particle is always conjugated for the irrealis mood.

zaggu umaadaij yi luj, a hiyaj yaadd vaddal. zaggu umaada-i -j yi luj, a hi -iya-j yaadd ddal. HYP sink -TEL-IRR 1S.POSS boat, COND exist-STA-IRR hole LOC. "My boat could sink if there is a hole in it."

The deontic mood (DEO) denotes an action that should happen, whether by obligation or logical progression. It's like a stronger hypothetical particle. The verb head of a deontic particle is always conjugated for the irrealis mood.

auv zij, daaya bimaj daridd. diri va luvi va au. auv zij, daaya bima-a -j daridd. diri va luvi va au. TEMP near.future, DEO fall-ATEL-IRR rain. CAU COP cloud(PL) COP gray. "Soon, the rain should fall because the clouds are gray."

The epistemic mood (EPIS) denotes an action or state that might have happened, however, the speaker is unsure due to lack of evidence. It can also be used as a weaker hypothetical marker. Verb heads of the epistemic particle must be in the irrealis mood. This mood marker also accompanies "I think" sentences which are typically constructed as "I think this. I may have a hammer."

garya yau vai. ibiz auwiniyaj yanuz guddi. gari -a yau vai. ibiz auwina -iya-j guddi. think-ATEL 1S.NOM 3Si.ACC. EPIS possess-STA-IRR hammer. "I think I have a hammer."

Relativizer Particles

There are four relativizer particles that are normally expressed initially in a relative clause and after the noun that relative clause modifies. These can also be used as copula.

| Copulative | COP

|

va | Indicated that the head is equal to something. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Possessive | POSS

|

na | Indicates that the head possesses something. |

| Active | ACT

|

gaun | Indicates that the head does something. |

| Locative | LOC

|

ddal | Indicates where the head is located. |

As relativizers, they can be translated as such: COP = which is, POSS = which has, ACT = which does, and LOC = which is located.

As copula, COP equates a subject noun with another noun, possessive pronoun, color, or number; POSS equates a subject noun with an adjective that's not a possessive pronoun, color, or number; ACT doubles as a gnomic aspect particle; and LOC indicates the location of the subject. Since these are particles, the word order for these particular types of sentences appears to change to SVO and the accusative particle is omitted (this does not apply to objects of a gnomic verb).

wizddaaniya va ggarimalun. wizddaaniya va ggarimalun. Wistania COP large.island "Wistania is a large island." "Wistania, which is a large island,..."

wizddaaniya na lazai. wisddaaniya na lazai. Wistania POSS great. "Wistania is great." (Lit. "Wistania has great.") "Wistania, which is great,..."

wizddaniya gaun liya. wizddaniya gaun liya. Wistania ACT fly. "Wistania fares well" (Lit. "Wistania flies.") "Wistania, which fares well,..."

wizddaniya ddal vimanbbaggu wizddaniya ddal viman-bbaggu. Wistania LOC sky -SUBE. "Wistania is under the sky." "Wistania, which is located under the sky,..."

Technically, these are incomplete sentences, indicating only a noun and a relative clause without a compliment. However, they are considered perfectly viable sentences.

Coordinating Particles

Wistanian coordinating particles come in four types: normal coordination, weak coordination, contrastive coordination, and alternative coordination.

Normal coordination (CO) is similar to the English "and". However, each item in the list is proceeded by the word ya.

dajyi ya dari ya lari. daji-i ya dari ya lari. hide-TEL CO boy CO girl. "The boy and the girl hid."

Weak coordination (WCO) refers to a co-actor in the sentence while keeping the focus on a specific item of the list, which is usually featured at the beginning of the list and without a particle. It is denoted with the word vil.

dajyi dari nuz lari. daji-i dari vil lari. hide-TEL boy WCO girl. "The boy hid with the girl."

Contrastive coordination (CCO) is equivalent to the English "but" and is expressed through the particle bbal.

auvin vaun liyiya, bbal gaunun vaun bauliyiya. auvi-n vaun liya-iya, bbal gaunu-n vaun bau-liya-iya. bird-PL GNO fly-STA, CCO fish-PL GNO NEG-fly -STA "Birds fly, but fish do not fly."

Alternative coordination (ALTCO) denotes a choice or alternative among a group of items in a list, equivalent to the English "or", and denoted with the word i. Like the normal coordinating particle ya, this particle is featured before each item in a list.

ja lu aa i garauvi i diyan a. ja -a lu aa i garauvi i diyan a. want-ATEL 2S.NOM ACC ALTCO water ALTCO juice Q. "Do you want water or juice?"

This alternative coordinating particle is also used to answer a multiple choice question.

(ja yau) i diyan. ja -a yau i diyan. want-ATEL 1S.NOM ALTCO juice. "I want the juice."

Honorifics

Wistanian has an honorific system with several unique features. Honorifics are used for almost everyone: familial relationships and close friendships, authorities and superiors, and people who are younger than you. They are often said after a proper noun and can take nominal morphology and replace 2nd person pronouns.

The formal honorifics that one uses depends on the age and respective rank of the second person:

| Inferior | Peer | Superior | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | iz | - | baada |

| Child | yi / yin | yi / yin | auzi / auzin |

Familial honorifics are used among close family members. These honorifics will change depending on culture and sometimes family. Children, in particular, have unique honorifics given by their parents, like a nickname. For example, a boy named Maudu could be given the honorific ravu (fast), and only his parents, aunts/uncles by blood, and grandparents can call him "Maudu Ravu". While his sister Zamara could be Zamara Viyaz (kind) to her parents.

The most common Familial Honorifics are included under Kinship Terms below.

Semantics

The Wistanian Lexicon currently stands at 500 words as of October 2018, with a goal of accomplishing 2,500 words by the end of the year. A minimum of 10 words are actively added to the lexicon almost every day.

Kinship

Wistanian kinship is a modified version of the Hawaiian system common in most Malayo-Polynesian languages. In this system, siblings and first cousins share terms with only a gender and age distinction. Mothers are usually given a term of endearment by their children (usually mu), but a child's aunts will also be called "mother" and the father and uncles will share terms as well. Most of Wistanian culture is ambilineal and matrifocal, so that children live and associate closest to their mother and her side of the family. For this reason, a child's mother's brother will often be just as much of a father figure as the child's biological father, who may or may not be involved in the family.

| English | Kinship Term | Honorific |

|---|---|---|

| male older brother or cousin | daran | bai |

| male younger brother or cousin | yida | |

| female older sister or cousin | madya | |

| female younger sister or cousin | yima | |

| uncle/aunt by marriage | imaun | baada |

| mother/aunt by blood | maumu | iv |

| father/uncle by blood | vauhi | anda |

| grandmother | aumi | ivi |

| grandfather | audi | andi |

| husband | yi daz | - |

| wife | yi laz | |

| child, offspring, son/daughter | jyam | Variable |

| grandchild | aujyam |

The Bwolotil people are more nuclear, consisting of only a mother, father, and one or two children. They have their own kinship terms from their language. Some Katapu people share the typical family structure and kinship terms. However, most family structures are extended so that families live amongst the mother's extended family, and fathers are usually present in the home. Most of their kinship terms also come from the Katapu language, but some Wistanian terms are borrowed as well.

Colors

needs polishing

Colors are particularly significant to the Wistanian culture. As much of their economy revolves around fruits, vegetables, and flowers, and their great responsibility to protect the colorful ajmastones, it is imperative to be able to accurately describe color on a near-daily basis. As a result, Wistanian has a massive vocabulary list dedicated to colors, including unique color terms for "red-orange" and "dark yellow" and three distinct terms for "red".

Colors in Wistanian are considered nouns, never as adjectives. Therefore, to express the color of an object, one would say, "S va C".

jiya yau jazari va raul. ja -iya yau jazari va raul. like-STA 1S.NOM bean COP red. "I like red beans." (Lit. "I like beans that are red.")

Likewise, to say "These beans are red", the same structure would be used.

jazari id va raul. jazari id va raul. beans PROX COP red. "These beans are red."

Or alternatively, and more commonly, one could express the color as the subject and use the locative copula, creating a form that means, literally "C is on S":

raul ddal jazari id. raul ddal jazari id. red LOC beans PROX. "These beans are red." (Lit. "Red is on these beans")

As for the color terms themselves, Wistanian has nearly thirty-two color terms, although some people groups may use more or less than those.

| iraa | raul nidda hagg |

uma |

| zuvil jaaru |

aurin | |

| bayaari | auwu | |

| zuwi | luz aubra |

|

| laumiz | ||

| aunya | jan bazu |

minan |

| gazida | ddi | |

| ayud | zaz iyad |

ainau |

| ivau | maura | |

| aana | liwa | |

| auzna | au garaji |

balan |

Numbers

under construction

Example Texts

coming soon...ish