Wistanian

Wistanian (IPA: /wɪsˈteɪni.ən/), natively known as anigaliylaun (IPA: /əˈniɡəˌlilɑn/), is the first constructed language (conlang) by world-builder, writer, and professional amateur Paul A. Daly, written in 2017. The language was created for a novel series. The first novel is near completion.

It is spoken on the fictional planet Vale, on a large, yet isolated, island called Wistania. The language developed as a pidgin between two different languages, eventually becoming the lingua franca among the five different people groups who dwell on the island. Wistanian is an analytical and head-initial language, with VSO word order and a moderately small phonological inventory.

Introduction

Setting

Wistanian is an auxiliary language spoken on the fictional island nation of Wistania. The language stems from a pidgin created between the Nati and Taliv languages during The Wistanian War. After the peace treaty was signed, the Katapu, who were allied with Nati and Taliv but inactive in the war, documented and refined the Nati-Taliv Pidgin for use in the newly established government. Wistanian features mostly Taliv grammar, Nati vocabulary, Katapu influences, many Bolotil loan words, and scientific terms, mathematics, and the lunar calendar derived from the work of the Uzin. Wistanian's native name, anigaliylaun, is a compound of ani (language) and galiylaun (peace). It is translated as "Peace Language."

The five different people groups of Wistania remained isolated from each other for part of the post-war era. However, trade and intermarriage became more commonplace, requiring a competent lingua franca. This is followed by religious evangelism by the Katapu, engineering from the Uzin, and entertainment from the Nati, all of which Wistanian was the primary language for distribution and promotion. Eventually, the language became taught as a mandatory subject in school. After only a couple centuries, Wistanian advanced from a government-only auxiliary language into the national language of the island, natively and fluently spoken by most of its citizens.

As a result, Wistanian is mostly regular, with a moderately small phonological inventory and vast dialectal variation. It is the most spoken and embraced by the Taliv and Nati people groups, and the least spoken by the Bwolotil people group, who often protest the language's difficulty. The other five languages are still spoken, especially the Bwolotil language. Both the Uzin and Katapu have important texts written in their languages, while Taliv and Nati have shifted into archaism, although they are still taught in school.

Goals

Wistanian was created with three goals in mind:

- To be naturalistic, yet unique. It should have its own unique phonology, grammar, and lexicon, not identical to any natural language on earth, but still naturalistic and sensible.

- To represent the Wistanian culture. This language was designed for songs and speeches, bedtime stories and battle cries, gentle wisdom and fierce ambition, hope and struggle. This language is designed for the Wistanians: their personality, their history, and their heart.

- To be novel-friendly. Crazy letters and long words will confuse and alienate most readers, which is why Wistanian was designed to have short, easily readable words that readers can enjoy, one small sentence at a time.

Inspiration

Like most first conlangs, Wistanian started as an English relex (but without tense and articles). However, after nearly four mass revisions over a year, Wistanian has become its own unique language. It's influenced by several languages, especially Spanish and Tamil, but their influence is mostly found in the lexicon while contributing only minimally to the grammar.

Phonology

Consonants

The consonants are as follows (allophones are in [brackets]):

| Labial | Alveolar1 | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | [ŋ]2 | |||

| Stop | voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||

| unvoiced | p | t | k | |||

| Fricative | v | z | ʒ | [ɣ]3 | ɦ | |

| Liquid | w ~ βʷ4 | ɾ ~ r5 | j | |||

| Lateral | l | |||||

- Alveolars (except /ɾ ~ r/) are pronounced laminally.

- n > ŋ / _[velar]<

- ɦ > ɣ / #_, [stress]_

- /w/ is spoken in emphasized or slow speech, while /βʷ/ is spoken in quick speech. Whenever immediately following a consonant, this is always pronounced as /w/. In the Western Dialect, it is always pronounced as /w/.

- /r/ is spoken in emphasized or slow speech, while /ɾ/ is spoken in quick speech. In some words, the trilled is preferred even in quick speech; for example, ggarauni (large) is almost always pronounced [kəˈrɑni].

Vowels

The vowels are as follows (allophones in [brackets]):

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i [ɪ]1 | ɯ [u]2 | |

| Mid | e | [ə]1 | |

| Low | a | ɑ [ɒ]2 | |

| Diphthong: ai̯ | |||

- All vowels lengthen when stressed.

- All vowels become breathy after /ɦ/.

- /i/ and /a/ shift to [ɪ] and [ə] whenever unstressed. The only exception is when /i/ follows /j/, /w/, or /l/ or is at the end of a word.

- /ɯ/ and /ɑ/ shift to [u] and [ɒ] after /w~βʷ/.

Phonotactics

Syllables take on a (C)(A)V(N) structure where A represents an approximant and N represents any consonant that is not /j/, /w/, or /ɦ/. The last consonant in a syllable should not equal the first consonant in the next syllable, and neighboring vowels are always separated with /ɦ/, except for /i/ and /ə/, which are separated with /j/.

Stress

Stress usually falls on the first non-lax vowel (/ai̯/, /i/, /e/, /a/, /ɯ/, or /ɑ/). The only issue with this is where the vowels /i/ and /a/ come into place since you must know whether or not those sounds are the stressed /i/ or /a/ or the lax [ɪ] or [ə]. A prime example is between the words viman and viman, which are spelled identically. When stress is on the /i/ as in [ˈvimən], the word means “sugar”, but when stress is on the /a/ as in [vɪˈman], the word means “sky.” Stress is realized through vowel lengthening, as is explained in more detail

Prosody

In Wistanian culture, speaking loudly is considered rude. Therefore, Wistanian language is typically spoken softly and clearly. It is arguably a stress-timed language that realizes stressed syllables and stressed words by lengthening vowel duration.

Orthography

Wistanian employs its own script, but it is romanized with a system that reflects the script and its spellings. The romanization rules are as follows:

- /m/, /n/, /b/, /d/, /g/, /v/, /z/, and /l/ are represented with the corresponding IPA symbol.

- /p/, /t/, and /k/ are represented by ⟨bb⟩, ⟨dd⟩, and ⟨gg⟩, respectively.

- /ʒ/, /ɦ/, /ɾ~r/, /w~βʷ/ and /j/ are represented by ⟨j⟩, ⟨h⟩, ⟨r⟩, ⟨w⟩, and ⟨y⟩, respectively.

- /ɯ/ and [u] are represented by ⟨u⟩.

- /a/ and [ə] are represented by ⟨a⟩.

- /i/ and [ɪ] are represented by ⟨i⟩.

- /ai̯/ is represented by ⟨i⟩, but is sometimes written as ⟨ii⟩.

- /e/ is represented by ⟨aa⟩.

- /ɑ/ and [ɒ] is represetned by ⟨au⟩.

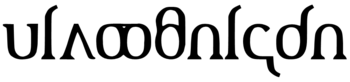

Script

Wistanian has an alphabet which represents the different sounds in Wistanian. The alphabet was inspired by Latin, IPA, and Greek, but is often described as Armenian-looking.

The script, often referred to as araman taliv vahigza (lit. "dishes of the Taliv) began its evolution during the Diwa oppression when the Taliv people were secretly plotting escape by setting their dishes outside their homes in certain orders to convey messages. After their escape and resettlement on the Wistanian island, the dishes gave form to the written language.

Another interesting feature of the script is "compound glyphs." They are /k/, /t/, /p/, /e/, and /ɑ/, and they are made by doubling or combining two different glyphs together. This is why the romanization of Wistanian uses ⟨gg⟩ for /k/, ⟨au⟩ for /ɑ/, as well as the other digraphs.

Like the lexicon and grammar, Daly redesigned the Wistanian script multiple times - three, to be exact. The original script was an alphabet, but it did not capture the "spirit" of Wistanian, so it was scrapped for an abugida. The abugida, which was beautiful, was also difficult to learn and write, prompting yet another redesign. The original design is now considered as the old Bolotil alphabet, while the abugida is an alternative script used by the Nati.

Syntax

Wistanian follows a rigid syntax and tight grammar. However, these strict standards, along with the simple phonology, help Wistanian people groups to remain understandable and intelligible among each other.

Word Order

Wistanian has Verb-Subject-Object word order (imperatives are VOS), modifiers that follow their head (except for possessive pronouns, numbers, and colors), post-positional suffixes, and particles that come before their head. Modifier phrases will usually come at the beginning or end of the sentence.

gaun azavyi ravu miramwi daz ilam aa din naulam ggarauni da zi maumu. gaun azavi-i ravu miram-wi daz ilam aa din naulam ggarauni da zi maumu. PFV.PST carry-TEL fast store-LAT man young ACC three melon large BEN 3Sa.POSS mother. "The young man quickly carried three large melons to the store for his mother." *carried fast store to man young three melons large for his mother.

Questions

Questions will typically follow the same syntactic pattern as declarative sentences, except with rising intonation. Typically, Yes/No questions will consist of a statement followed by zau/baun (Yes/No). "Who/What/When/Where/Why" questions will either follow the same declarative-question word pattern, or include a question particle as the object.

raul magin va. zau? table REL.has red. yes? "Is the table red?”

rol magiyn va. ari? table REL.has red. why? “Why is the table red?”

luva zaun? 2S.NOM-COP who? “Who are you?”

There is no Wistanian equivalent to the English "how," usually being replaced by "what" or "what method".

Morphology

Nouns

Wistanian nouns come in three classes: proper, improper, and pronouns. Proper nouns refer to names of people or places ("Wistania", "Alija"), while improper nouns refer to generic terms (e.g., "country", "man"), and pronouns refer to substitute words for other nouns and noun phrases. Proper nouns are never inflected, however, improper nouns can be inflected for number and position, be compounded, or undergo derivational morphology to become a verb or modifier. Pronouns can take on more inflections than improper nouns.

Number

Wistanian has three grammatical numbers: singular, paucal, and plural. Proper nouns do not inflect for number at all, improper nouns only distinguish between paucal and plural, while pronouns only distinguish singular and plural. This unique distinction arose as a result of Middle Taliv, which had a singular/paucal/plural distinction, then merged the paucal and singular before it transitioned to New Taliv. The pronouns, however, maintained the singular/paucal/plural distinction, then later lost the paucal, resulting in a singular/plural distinction in pronouns.

Location

Nouns distinguish ten locative cases, all of which come from the Nati language and were adopted into the Taliv language during the pidgin era:

| Inessive | -ddal | ujadiddal | "in the house" |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elative | -al | ujadyal | "outside the house" |

| Lative/Dative | -wi | ujadiwi | "to/toward the house" |

| Ablative | -igza | ujadyigza | "(away) from the house" |

| Adessive/Genitive | -nuz | ujadinuz | "near/of the house" |

| Distantive | -bin | ujadibin | "far from the house" |

| Superessive | -jazid | ujadijazid | "above/over the house" |

| Subessive | -bbaggu | ujadibbaggu | "below/under the house" |

| Antessive | ? | ? | "before/left of the house" |

| Postessive | ? | ? | "after/right of the house" |

? indicates that a term for the particular case has not been decided upon.

Once a noun takes on a locative case, it is treated as a modifier, coming immediately after its head. However, it can still be given modifiers of its own that may intervene between the locative and its head. In this case, locative nouns take on their own group, alongside subject nouns and object nouns.

buda yau yi ujadiwi ujan. buda yau yi ujadi-wi ujan. walking 1S.NOM 1S.POSS house-LAT green. "I am walking to my green house."

Verbs

Verbs only conjugate four lexical aspects. There is no tense, but it is rather expressed through context and other modifier phrases. Only the irrealis mood is conjugated to the verb, while other moods are expressed through modifiers and context. Verbs do not compound with any other part of speech.

Aspect

The Wistanian understanding of aspect is different than what one will find in most natural languages. Rather than conjugating for grammatical aspect, Wistanian conjugates for lexical aspect. In other words, the very definition of a verb may change based on its conjugation.

The four lexical aspects are: Stative (STA), Durative (DUR), Telic (TEL) and Atelic (ATEL).

- Stative verbs (

STA) describe a situation or action that is unchanging over a long period of time. Stative verbs do not describe temporary actions, but rather the result of a temporary action or a series of temporary actions that identify the subject. - Durative verbs (

DUR) are dynamic and indicate that an action is in progress from one state to another. - Telic verbs are dynamic and punctual, describing an action with an endpoint. More specifically, it refers to any action that has been completed as intended. In most situations, it strongly implies the past or future tense and the perfective grammatical aspect.

- Atelic verbs (

ATEL) are dynamic and punctual, describing an action that does not have an intended endpoint. Like the telic, this aspect strongly implies the past or future tense, but is often grammatically imperfective.

ASPECT

/ \

STATIVE DYNAMIC

/ \

DURATIVE PUNCTUAL

/ \

TELIC ATELIC

For example, the verb bima means to "fall" in the telic, "precipitate" in the atelic, "descend" in the durative, and "to be fallen (i.e., lying on the ground after a fall)" in the stative. bima still expresses the same basic meaning — "the subject goes downward" — but its implications change based on its conjugations. This is also true of the verb ja, which means "like" in the stative, "fall in love" in the durative, "achieve or accomplish" in the telic, and "want" in the atelic. Again, the basic meaning remains — "the subject has a desire" — but the differing conjugations further explain what kind of desire is being had: an unchanging desire (stative), a growing desire (durative), a satisfied desire (telic), or an unsatisfied desire (atelic).

These aspects also imply certain grammatical features. Indeed, these aspects originally did refer to grammatical aspects a thousand years within Wistanian's history. The stative was once the gnomic aspect, the durative was once the continuous aspect, and the telic and atelic were once the perfective and imperfective aspects, respectively. This shift was slow, however, but it picked up mightily during the pidginization with the Nati, since lexical aspect could allow them to communicate using fewer verb roots, so words such to "to put on" were replaced with the durative conjugation for "to wear".

Mood

Verbs are conjugated for the irrealis mood, which is used in polite requests, questions, and in conjunction with epistemic or deontic particles. This is done with the suffix ⟨-j⟩. Indicative negative verbs are not conjugated for the irrealis.

| NOMINAL | VERBAL | |||||||

| STATIVE | DYNAMIC | |||||||

| DURATIVE | PUNCTUAL | |||||||

| TELIC | ATELIC | |||||||

| realis | irrealis | realis | irrealis | realis | irrealis | realis | irrealis | |

| viga | vigiya | vigiyaj | viga | vigaj | vigai | vigaij | viga | vigaj |

| zani | zaniya | zaniyaj | zana | zanaj | zanyi | zanyij | zanya | zanyaj |

| hadu | hadiya | hadiyaj | hada | hadaj | hadwi | hadwij | hadwa | hadwaj |

Modifiers

Modifiers immediately follow their head, except for colors, numbers, and possessives. Morphologically, there is no difference between an adjective and an adverb, since they rely on word order. Modifiers also provide some verb modality and postpositional contructions.

Adpositions

There are two types of adpositions in Wistanian:

Locative/Directive adpositions are tagged at the end of a noun root, acting as a postposition, similar to the word homeward. (E.g., ujadi-ddal // house-in // "in the house"). These words must always be featured immediately after the verb.

Purpose adpositions, such as the benefactive and instrumental, act as separate prepositional words. These phrases can be expressed at the beginning of the sentence, the end of the sentence, or after the verb.

Converbs

There are a few converbs, which act differently than other verbs. The most important of theses converbs is va which essentially means "which is" and is used as a copula, auxiliary verb, and relative conjunction.

As a copula, the word order is psuedo-SVO. Technically, there is only the subject, a relative particle, and an object of the relative clause, and the following sentence is a fragment, which are legal in Wistanian grammar.

viddaru va garauda.

fruit COP food.

"fruit is food."

As an auxiliary verb, it acts as the gnomic particle.

va viga dari aagarauda

GNO.PRS eating boy ACC-food

"The boy eats food."

As a relative conjunction, it can be translated as "which is."

viga dari aaviddaru va garauda.

eating boy ACC-fruit which.is food.

"The boy is eating fruit, which is food."

There are two other converbs: na (having/which has/possessive) and vaun (doing/which does/perfective). These converbs work almost identically with va.

Honorifics

Wistanian has a very exciting honorific system with several unique features. Honorifics are used for almost everyone: familial relationships and close friendships, authorities and superiors, and people who are younger than you. They are often said after a proper noun, take inflectional morphology, and can replace the 2nd person pronouns.

Example texts

auv lin zun, buda yau, ya gaun inja yau aagawaz garani id. auv yum, gaun bbiyra yau aagawaz, ya ddal lin vaggan min min vilauwa. ya yiga yau; gaun auwina gawaz idzau aahiyari.

during one day, walking 1S.NOM, and PFV.PST finding 1S.NOM ACC-log big PROX. during next, PFV.PST roll 1S.NOM ACC-log, and LOC one stick little little 3SI.NOM-under. And saying 1S.NOM; PFV.PST possessing log DIST child.

"One day, I was walking, and I found this big log. Then, I rolled the log over, and underneath was this tiny little stick. And I was like, “That log had a child!”

— from "Seagulls (Stop It Now)" by Bad Lip Reading