Rttirri

| Rttirri | |

|---|---|

| Rttirriapu | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [[w:Help:IPA|ʈʼiɻiɑpu]] |

| Created by | – |

| Setting | Rttirria |

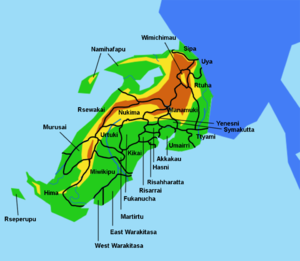

| Native to | All of Rttirria, though less prevalent in Sipa, Uya, Rtuha, and Wimichimau |

| Native speakers | 46.5 million (2015) |

Rttirrian

| |

Rttirri (English: /ˈtɪəri/, homophonous with "teary") is the official language of Rttirria, a nation in Southeast Asia that forms a peninsula in the Bay of Bengal, along the southwestern coast of Myanmar. It is spoken as the native language of 46.5 million Rttirrian citizens, or just under 80% of the nation's total population of 58.2 million. Most other citizens have at least some proficiency in the language.

Rttirri is dialectally diverse, with many different accents found across the nation. It uses the Rttirri script, an abugida that evolved from the Pallava script, which is a Brahmic script. Other Pallava scripts include Thai, Lao, Burmese, and Khmer. However, an English transcription system was codified in the late 19th century, and is used on this page for convenience.

Linguistically, Rttirri is classified as an ergative-absolutive, polysynthetic language. It has a phonology consisting of only four vowels (in the standard language) and 25 consonants. It is fascinating to linguists because of its unique method for marking the causative agents of verbs: inflectional particles that encode the person and number of the causative entity, just like the ones used to mark the ergative and absolutive agents.

History

- See also: Proto-Rttirrian

Rttirri is a member of the Rttirrian language family, whose languages are spoken across the nation of Rttirria as well as in adjoining areas of Myanmar and Thailand. It is part of the South Rttirrian branch of the family; the dialects of Proto-South-Rttirrian that would become Rttirri split off from those that would become Gaju around the 3rd to 5th century CE, probably in southeastern Rttirria.

The main phonological and grammatical changes from Proto-South-Rttirrian to Rttirri are summarized here:

- The language evolved from a nominative-accusative to an ergative-absolutive language: intransitive verbs began to use a construction combining the subject/possessive marker with the word hi ("benefit"), which then simplified into an affix identical to the object markers. For example, na-hi- ("for my benefit, X happened") became ni- ("I did X").

- The third-person singular absolutive affix */gʲa/ disappeared.

- A chain shift occurred from voiced stops, to voiceless stops, to voiceless fricatives, much like Grimm's law in Proto-Germanic. This occurred for the alveolar, bilabial, palatal, and retroflex series, but the palatalization of */gʲ/ kept it from occurring for the velar series—i.e. */gʲ/ did not become /k/ and /k/ did not become /x/. Instead, */gʲ/ shifted to simply /j/.

- Some clusters were broken up with an epenthetic */ə/, which later backed to /ʌ/.

- In onset position, the phoneme */ʟ/ shifted to /ʋ/, later /w/. In coda position, it vocalized to /u̯/, except after /u/—*/uʟ/ > /ʌ/.

- In some "emphatic" and common words, stops were optionally pronounced as ejective consonants. Under the influence of this phenomenon, all stop-stop clusters simplified to an ejective version of the first stop, e.g. */tk/ > /tʼ/.

- /β/+/ʌ/, in either order, simplified to a new vowel, /y/, which later lowered to /ø/ to contrast with /i/.

- The verbal tense system simplified greatly, with only a handful of irregular verbs remaining (see below).

- The freestanding evidential particles na, nye, su, and sya began to be attached to the verb and take on the preceding vowel.

- Similarly to the formation of the new absolutive prefixes, causative prefixes formed from the ergative/possessive prefixes plus efe (modern Rttirri: ehe "command"), which simplified. For example, na-ehe ("under my command, X happened") became ne- ("I caused X to happen").

- Because the word order (which is much freer in Gaju, for example) was starting to solidify in an Verb / Absolutive / Ergative pattern, the absolutive noun joined the verb complex, leading to noun incorporation.

- Two more chain shifts occurred: /θ/ > /f/ > /h/, /t͡s/ > /t/ > /ʔ/.

- The phoneme */s/ merged into /ç/ before front and central vowels and /ʃ/ before back vowels.

- In most dialects, */a/ (which had backed to /ä/) merged with /ʌ/ as /ɑ/.

Phonology

The vernacular of the Rttirrian people is a language like no other; aside from the smaller languages of the mountain-peoples and forest-peoples. It is spoken variously with curls of the tongue like the languages of the South Asian subcontinent and of Australia; and with glottalized puffs of air like the Navaho language and the families of the Caucasus Mountains; and a front-rounded vowel thieved from the Scandinavians... I am optimistic that, after proper study, the Rttirrian tongue may one day show an affinity with one of the many ill-understood language families of northern Australia or New Guinea...

Consonants

Although the specific realizations vary, the dialects of Rttirri generally distinguish the same consonant phonemes.

| Labial | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | rn /ɳ/ | ny /ɲ/ | ||

| Plosive | p /p/ | t /t/ | rt /ʈ/ | ty /c/ | k /k/ | hh /ʔ/ |

| Ejective | pp /pʼ/ | tt /tʼ/ | rtt /ʈʼ/ | tty /cʼ/ | kk /kʼ/ | |

| Fricative | f /f/ | s /ʃ/ | rs /ʂ/ | sy /ç/ | h /h/ | |

| Affricate | ch /t͡ʃ/ | |||||

| Approximant | w /w/ | rr /ɻ/ | y /j/ | |||

| Flap | r /ɽ/ |

In addition, the consonants l /l/ and kh /x/ are used in loanwords.

Vowels

Modern Standard Rttirri has a four-vowel inventory.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i /i/ | u /u/ |

| Mid | e /ø/ | |

| Low | a /ɑ/ |

In addition, the mid vowels e /e/ and o /o/ are used in loanwords.

Phonotactics

Modern Standard Rttirri does not allow final consonants, and the only initial clusters allowable are of the following form: (f s sy) + (m n r rr). There are no geminate consonants.

No dialects of Rttirri distinguish vowel length, but the following diphthongs are allowed: ai au ei eu ui iu.

Stress is usually on the first syllable of a word, with secondary stress applied to every subsequent odd-numbered syllable. Loanwords and foreign names typically preserve their original stress, however.

The glottal stop, hh, which is fairly rare in lexical units, is used to separate morphemes to avoid two consecutive identical vowels.

- Ki-kani-ni.

- 2SG.ABS-listen-DRPAC

- You listen.

- Kihh-isi-ni.

- 2SG.ABS-talk-DRPAC

- You talk.

Orthography

The Rttirri script was codified in the mid-14th century. It was based on the Pallava script, which is a Brahmic abugida that is also the ancestor of the Thai, Lao, Burmese, and Khmer scripts.

As an abugida, the Rttirri script is written with consonantal letters that are mutated for the different vowels. /i/ is the inherent vowel - for example, the character for /m/ is pronounced /mi/, but when given the diacritic for /u/, it is pronounced /mu/.

The writing system in Rttirri is mostly phonetic, but as it reflects Classical Rttirri pronunciation, various mergers and phonemic splits have corrupted the one-to-one correspondence between sound and letter. In addition, several characters exist that are only used for transliteration of Sanskrit words into Rttirri, having historically represented sounds that do not exist in Rttirri. For example, the letter representing Sanskrit /ɖ/ is distinct from the letter representing /ʈ/, but both are pronounced as [ʈ] in modern Rttirri (or often as [ɖ] intervocalically), because most dialects of the language have no phonemic voicing distinctions. The diacritic representing /ʌ/ could be considered redundant, because few speakers today maintain the phonemic distinction between /ʌ/ and /ɑ/, but using the right diacritic anyway is essential for correct spelling.

In the late 19th century, when Rttirria was a colony of Britain, linguists from England designed a Latin transcription system for Rttirri. There have been periodic movements to switch Rttirri to using the Latin alphabet, but none has ever been successful. However, the Latin system is often favored for textbooks and travel guides for learning Rttirri, since it is almost completely phonetic.

Vocabulary

The bulk of Rttirri vocabulary is indigenous. However, a sizable number of words, particularly related to food, seafaring, academia, and religion, are derived from Arabic and Sanskrit; as part of the historical Indosphere, Rttirria was long influenced by Indian and Arab traders and briefly made a colony of India, during which time it was given its native Brahmic script. Rttirrians' attitudes toward loaning words from other languages, such as English, Mandarin, Burmese, and Tamil, vary more.

However, many common "international" words have names coined from native Rttirri roots. This is not primarily a prescriptive process propagated by a nativist language academy, but has more to do with marketing firms' desire to make products accessible and comprehensible, and with Rttirri's limited phonotactic possibilities that make many languages' vocabulary difficult to loan. A few examples follow:

- makawei ("chocolate", lit. "sweet dirt")

- Pisyikitepe ("Internet", lit. "electricity book" - this may be seen as ironic, since kitepe is itself an obvious Arabic loan)

- uiuiuni ("banana", lit. "crescent")

Numerals

Native Rttirri numerals only go up to five, with the words for "four" and "five" being formed through reduplication; there are also native words for various other small quantities, including zero. However, these numerals exist in tandem with numbers loaned from Sanskrit. For numbers where Rttirrian and Sanskrit versions exist, the Sanskrit root tends to be used in compounds and in higher-register terms, similar to prefixes like mono- and bi- in English. An example is tefettarri ("bicycle", lit. "two-wheel").

| Number | Rttirrian Root (where applicable) |

Sanskrit Root (where applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | parta | sunya |

| many (traditionally, more than five) |

kuie | |

| a few (traditionally, 2 - 5) |

murri | |

| 1 | e | ekama |

| 2 | tau | tefe |

| 3 | kui | tereni |

| 4 | tauau | chafari |

| 5 | kuiui | pacha |

| 6 | sata | |

| 7 | sappa | |

| 8 | asata | |

| 9 | nafa | |

| 10 | tasa |

Dialectology

Rttirri has many regional dialects.

Modern Standard Rttirri

The modern standard variant of the language is not spoken natively by many native Rttirrians, except those from highly educated and wealthy families, but it is widely used in news broadcasts and automated recordings such as those on subway systems - in this respect, it occupies a similar niche to that of Received Pronunication in the UK. It is characterized by the following features:

- Because the usual aim of MSR is to "speak clearly", allophony is minimized - for example, consonants are not voiced intervocalically as they are in most dialects, and /w/ remains phonetically [w].

- The vowels /ɑ/ and /ʌ/ are merged to /ɑ/; thus, words like /tɑwi/ "brick" and /tʌwi/ "to survive" are pronounced the same.

Eastern Rttirri

Eastern Rttirri is spoken in much of the eastern half of the country, from the border with Myanmar to Fukanucha and eastern Kikai. This area of the country, centered on the capital city of Iharnara, is known for its large immigrant communities, decaying industry, high crime, and shrinking population, comparable to the Rust Belt of the United States. Eastern Rttirri, which is considered the most innovative dialect, is characterized by the following features:

- Intervocalically within a word, voiceless consonants are voiced.

- /ɑ/ and /ʌ/ are merged to [ä].

- After palatal consonants and in the last syllable of a word, it is raised as far as [e].

- /ø/ lowers to [œ].

- After retroflex consonants and in the last syllable of a word, it is instead backed as far as [o].

- /h/ fronts to [x] before phonetically front vowels, or [χ] before back ones.

- /w/ is realized as [b] in all positions. In loanwords and foreign names, /w/ is often rendered as a full [u] instead, while /b/ is increasingly imported as a fully voiced [b] instead of as [p].

- /j/ becomes a fricative sound, [ʝ]. Likewise, diphthongs containing /i/ become /Vʝ/ or /ʝV/ sequences. This pattern is not usually applied to loanwords.

- /i/ is backed to [ɨ~ɘ] after retroflex consonants, and /u/ is fronted and unrounded to the same vowel after palatal consonants - in word roots, but not in affixes, determiners, or certain other function words. Many scholars argue that there has been a phonemic split and that /ɨ/ is a legitimate vowel in Eastern Rttirri.

- One minimal pair is rra-rri ("cozy", lit. "home-y") [ɻäɻi] vs. rrarri [ɻäɻɨ] ("footprint").

- Eastern Rttirri shows extensive reduction of unstressed vowels, creating clusters that do not exist in other dialects.

- Diphthongs are pronounced more as /VV/ sequences with a hiatus.

- The evidential particles lose their final vowels, instead being pronounced as bare consonants.

- The past-tense affix -pu- becomes simply -p.

Fukanucha Rttirri

The advanced sub-dialect of Fukanucha shows the following additional features:

- The already fronted /ɑ/ is further fronted to [a].

- The already lowered /ø/ is unrounded to [ɛ~æ].

- The -n evidential particle may be realized simply as nasality on the preceding vowel. Likewise, the -ny evidential particle may be realized in the same way, with the addition of a final [ʝ].

Yenesni Rttirri

Another advanced sub-dialect of Eastern Rttirri is spoken in most of Yenesni and southern Manamuki, showing the following additional features:

- The already lowered /ø/ is unrounded to [ɛ].

- The "Yenesni Shift" is a chain shift of several vowel phonemes after labial consonants, except in most foreign names, affixes, and function words. The shift is considered to be in progress, and it may be spreading to Akkakau and other Eastern provinces; younger speakers in Akkakau appear to be showing the early stages of the Yenesni Shift. It is sporadically found in younger speakers in urban areas of the West.

- /i/: [i] > [e]

- /e/: [e] > [ɛ]

- /ø/: [ɛ] > [ä]

- /ɑ/: [ä] > [ɒ~o]

- /o/: [o] > [u]

- By analogy with the past-tense -p-, the future-tense -mi- becomes -m-, and is pronounced [ŋ] before velar consonants.

Western Rttirri

Western Rttirri is used in most of the western half of Rttirria, from western Kikai to the beaches of Hima. This area of the country, centered on Rttirria's largest city, Efunari, is wealthier, more ethnically homogeneous, and increasingly culturally relevant. However, in recent decades the dialect has also begun to creep up to the sparsely populated north of Rttirria. The dialect's high cultural prestige and the rapid growth of the northern city of Tettufane (many of whose residents are from Hima or the Efunari area), are starting to solidify Tettufane as a Western Rttirri-speaking city. Western Rttirri is characterized by the following features:

- Intervocalically within a word, voiceless consonants are voiced.

- Intervocalically within a word, /w/ is fricativized to [v]. In this position, it merges with /f/, which is voiced to [v].

- Most speakers merge /ɑ/ and /ʌ/ to /ɑ/; however, some older and rural speakers maintain the distinction.

- In all positions, /ʔ/ disappears.

- When stressed, /i/ and /u/ diphthongize to [əi] and [əu].

- The diphthongs /ɑi/ and /ɑu/ tense to [oi] and [eu].

- This tensing does not take place when these diphthongs are formed by elision of /ʔ/. Thus, kau (/kɑu/) "to want" and kahhu (/kɑʔu/) "to squeeze" are distinguished not by a glottal stop, but by the vowels: [keu] vs. [kɑu].

- In all positions, /ø/ raises to [y].

- The diphthong /øi/ merges with it.

- The past-tense affix -pu tends to be substituted with the past-perfect affix -fe.

Kikai Rttirri

Kikai occupies a transitional zone between the Western and Eastern dialect areas. As a result, its dialect can be considered a mixture of Eastern and Western Rttirri, but younger speakers, especially in the city of Kikai itself, are adopting more Western features.

Northern Rttirri

Spoken only by rural and isolated communities in northern Rttirria, and by older people in the Tettufane metropolitan area, this dialect is being crowded out by the influence of Western Rttirri. One of the most conservative dialects, it is characterized by the following features:

- Unlike in other dialects, voiceless consonants remain voiceless between vowels.

- Likewise, /w/ is pronounced clearly as [w] in all positions.

- The distinction between /ɑ/ and /ʌ/ is maintained.

- The value of /ø/ is typically [ø] in all positions.

- After retroflex consonants, /i/ and /u/ lower to [e] and [o].

- When not stressed, the diphthong /ɑu/ merges with [o]. As a result, some scholars argue that /o/ is its own phoneme in Northern Rttirri.

- The consonants /t͡ʃ/ and /c/ have lost their phonemic contrast and become allophonic: [c] is pronounced after front vowels and [t͡ʃ] after back ones.

Rseperupu Rttirri

Localized to the small island province of Rseperupu, off the coast of western Rttirria, Rseperupu Rttirri is characterized by the following features, influenced by the native languages of indigenous, non-ethnically-Rttirri peoples.

- Intervocalically within a word, voiceless consonants are voiced.

- Intervocalically within a word, /w/ is fricativized to [v].

- Stressed vowels tend to be allophonically lengthened.

- /ɑ/ and /ʌ/ are merged to [ä].

- /ø/ is unrounded to [e].

- /u/ is lowered to [o].

- Except for /j/, palatal consonants are shifted to an alveolar articulation.

- /ç/ is realized as [s], /c/ as [ts], and /cʼ/ as [tsʼ].

- /ɳ/ is merged into /n/.

Morphology

Verbs

The Rttirri verb is richly polysynthetic, and contains the following slots for affixes. Slots marked with a † are required for all verbs.

| Verb Slot | Allowable Inputs |

|---|---|

| Causative Agent Person/Number |

ne- (I) ke- (you) we- (he/she/it) me- (we) te- (you all) rte- (they) |

| Ergative Agent Person/Number |

na- (I) ke- (you) wa- (he/she/it) ma- (we) ta- (you all) rta- (they) |

| Absolutive Agent Person/Number (†) |

ni- (me) ki- (you) ∅- (him/her/it) mi- (us) ti- (you all) hhi- (them) |

| Mood | -sya- (optative) -ppa- (adhortative) -mappa- (cohortative) -tya- (interrogative) -nai- (subjunctive) -kai- (conditional) -kka- (imperative) -sma- (generic) |

| Past Tense | -pu- |

| Verb Root (†) + Question Infix |

any verb |

| Auxiliary Verb | -kaki- ("to be able to") -kau- ("to want to") -rtika- ("to like to") and others |

| Future Tense | -mi- |

| Incorporated Noun (for transitive verbs) |

any noun root, without adjectives, determiners, possessive affixes, etc. |

| Evidentiality (†) | -nV (direct knowledge) -nyV (hearsay) -sV (inferential) -syV (assumptive) (V = the vowel of the preceding syllable) |

Irregular verbs

Rttirri has 20 irregular verbs, which have special forms for the past and future inflections. However, when used with a modal verb, this irregularity is ignored, so the normal affixes -pu- and -mi- are used.

- Ni-tutasa-na.

- 1SG.ABS-walk.PST-DRPAC

- I walked.

- Ni-nitasa-na.

- 1SG.ABS-walk.FUT-DRPAC

- I will walk.

- Ni-pu-tasa-kaki-ni.

- 1SG.ABS-PST-walk-can-DRPAC

- I was able to walk.

- Ni-tasa-kaki-mi-ni.

- 1SG.ABS-walk-can-FUT-DRPAC

- I will be able to walk.

The following irregular verbs exist:

| Verb (Past) |

Verb (Present) |

Verb (Future) |

English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| pui | fei | mui | to be |

| pisu | chiu | misu | to do |

| tyusymu | symu | nyisymu | to make |

| ppeu | kkeu | mepeu | to see |

| tufnu | fnu | nifnu | to bring |

| tuausma | ausma | niausma | to call |

| tuttaka | ttaka | nittaka | to feel |

| pumi | mupi | mumi | to believe |

| tutasa | tasa | nitasa | to walk |

| fupaki | haki | fumaki | to stay |

| tyusymi | symi | nyisymi | to exist |

| tuaihiu | aihiu | niaihiu | to get |

| upei | pei | umei | to think |

| tuicha | icha | nicha | to come |

| rtuertau | ertau | rniertau | to use |

| tuaihu | aihu | niaihu | to try |

| tyuyana | yana | nyiyana | to cook |

| puppi | ippi | muppi | to start |

| pafa | kafa | mafa | to return |

| puwa | euwa | muwa | to take |

Wh- questions

Non-binary questions (ones where the answer is not a simple "yes" or "no") are expressed in two different ways.

For "who"/"whom" and "what" questions, an affix is substituted for one of the person/number affixes on the verb:

- fe- (causative)

- fa- (ergative)

- fi- (absolutive)

- Ke-fi-pu-chi-nu uhiki?

- 2SG.ERG-what.ABS-PST-eat-DRPAC today

- What did you eat today?

Other non-binary questions are expressed by infixing one of the following particles within the verb root, after the first syllable of the root.

- -hhifi- ("when?")

- -hhifai- ("where?")

- -hhifau- ("why?")

- -hhifui- ("how?")

- Tihh-isi-ni mumu nu...

- 2PL.ABS-talk-DRPAC IMPF NEG

- You guys aren't talking...

- Tihh-ihhifausi-ni mumu nu?

- 2PL.ABS-talk.why-DRPAC IMPF NEG

- Why aren't you guys talking?

Noun incorporation

Only the bare stem of a noun can be incorporated into a verb. To add more information about a noun, one must do so outside the verb complex.

- Yuhhu, ke-∅-pu-chi-tufakha-sya na-tufakha anai!

- hey 2SG.ERG-3SG.ABS-PST-eat-apple-ASS 1SG.GEN-apple sweet

- Hey, you ate my sweet apple!

However, any type of noun stem can be incorporated, even proper names and compounds.

- Na-hhi-puhh-uffrai-waira-rnamu-nu.

- 1SG.ERG-3PL.ABS-PST-break-eye-bottle-DRPAC

- I broke the binoculars. (lit. "I broke the eye-bottles".)

- Na-∅-pu-emei-Nuyorroko-no uhhu.

- 1SG.ERG-3SG.ABS-PST-hate-New_York-DRPAC always

- I always hated New York.

In informal speech, a lengthy noun may optionally be substituted with a shorter one outside the verb complex - this can be seen as analogous to the classifier systems used in the Oneida language making use of noun incorporation. For instance, the sentence Yuhhu, kepuchitufakhasya natufakha anai! could instead be expressed as Yuhhu, kepuchitufakhasya nachipu anai!, where chipu simply means "food". The "alternative" noun used outside the verb complex need not be a literal equivalence or even phonetically shorter at all, so this is technique is frequently used for poetic effect.

However, the technique may be generalizing: studies show that younger speakers are using it in daily conversation more often, and with a smaller variety of "simplified" nouns. It is speculated that it may eventually evolve into a true classifier or grammatical gender system.

Sequential verbs

Rttirri allows strings of verb roots to be stacked inside the verb complex, such as when someone is doing multiple things in a row. There are three affixes that can join verb roots: ki for actions that take place in succession, i for actions undertaken simultaneously, and hu (lit. "and") for general sets of actions with no respect to chronology. All three of these affixes can be combined within a string of verb roots as needed.

- Ni-puhh-uweu-i-fusi-ni.

- 1SG.ABS-PST-sing-and-bathe-DRPAC

- I sang while I bathed.

To combine an intransitive verb with a transitive verb, which is undertaken by the agent of the intransitive verb, one may use the antipassive suffix -tyu on the transitive verb, and the suffix -kka (lit. "to") on the transitive verb's recipient.

- ∅-Pu-nyarra-hu-pikau-tyu-Wuikiu-nu ma-ttu-kka.

- 3SG.ABS-PST-yell-and-slap-ANTIPASS-Mother-DRPAC 1PL.GEN-self-DAT

- Mother yelled and slapped us.

Alternatively, the passive suffix -rui may be applied to the intransitive verb.

- Wa-mi-pu-pikau-rui-hu-nyarra-Wuikiu-nu.

- 3SG.ERG-2PL.ABS-PST-slap-PASS-and-yell-Mother-DRPAC

- Mother slapped us and yelled.

Causatives

Causative constructions are fairly common in Rttirri, used to express many actions that in other languages would be expressed as regular transitive verbs.

- Ne-wa-hhi-pu-chi-nerri-ni synapi pipi.

- 1SG.CAUS-3SG.ERG-3PL.ABS-PST-eat-carrot-DRPAC rabbit a_bit

- I fed my rabbit some carrots.

There is no inherent level of force communicated by a causative, so one can use adverbial particles such as kuni ("willingly") and mika ("reluctantly") to specify "to let X do Y" or "to make X do Y".

- We-na-∅-pu-kkai-wesipi-ni mika Sawikiu.

- 3SG.CAUS-1SG.ERG-3SG.ABS-PST-write-homework-DRPAC reluctantly Father

- Dad made me do my homework.

- We-ni-pu-ppa-na kuni Sawikiu tukai-kka ramui-huppu-nye!

- 3SG.CAUS-1SG.ABS-PST-go-DRPAC Father match-DAT square-ball-GEN

- Dad took me to the baseball game!

Equative sentences

The copula, fei (past: pui, future: mei), is an intransitive verb, and the thing or person that is being equated to is marked with -kka.

- ∅-Fei-Charartu-nu na-mahai-pu-kka.

- 3SG.ABS-be-Charartu-DRPAC 1SG.GEN-call-GER-DAT

- Charartu is my name.

Nouns

Compared to verb inflection, noun inflection in Rttirri is fairly simple.

All nouns are pluralized with -ma, and this suffix is maintained when a specific number is used. However, the plural suffix eliminates the need for any inflection on determiners or adjectives.

- irtu hhike

- tree that

- that tree

- irtu-ma symui kuiui hhike na-fuka-pu

- tree-PL tall five that 1SG.GEN-yard-LOC

- those five tall trees in my garden

Nouns have no grammatical gender, although the affix -kasi can be optionally used to explicitly "switch" their natural gender. Typically, masculinity is assumed, but there are exceptions.

- kkai-urri

- write-AGENT

- author (male)

- kkai-urri-kasi

- write-AGENT-F

- female author

- mirna-urri

- tend-AGENT

- nurse (female)

- mirna-urri-kasi

- tend-AGENT-M

- male nurse

- rnu-kasi

- man-F

- feminine-acting man

- pune-kasi

- woman-M

- masculine-acting woman

Possession

Like Arabic, Rttirri nouns may be inflected for possessor, using the ergative prefixes.

- na-puki

- 1SG.GEN-dog

- my dog

Rttirri is considered a pro-drop language, but when emphatic pronouns are used, they are formed with -ttu ("self") in this way.

- Ke-hhi-pu-enai-syi ke-ttu!

- 2SG.ERG-3PL.ABS-PST-kill-INFER 2SG.GEN-self

- You killed them!

Postpositions

Nouns can take the following postpositions:

| Postposition | English Translation |

|---|---|

| -pu | inside, among |

| -kka | to |

| -hha | from |

| -ri | at, worth |

| -rta | with (comitative) |

| -rratye | with (instrumental) |

| -nupe | above |

| -pe | below |

| -rnaha | in front of |

| -fani | in back of |

| -ppirsa | outside |

| -nye | of, near |

| -fappe | far from |

| -sya | across |

| -chatta | through |

| -pimi | between (2 people/things) |

| -tyeri | among (3+ people/things) |

| -wenyi | except |

| -fu | only |

| -niwa | around |

| -hara | about |

| -hhui | for |

| -misu | like, similar to |

The noun affixes are not clitics; all other words modifying the noun come after them both.

- ∅-Pu-wikka-na wa-rra-ma-kka rasi tau.

- 3SG.ABS-PST-run-DRPAC 3SG.GEN-house-PL-DAT red two

- She ran to her two red houses.

Derivation

Words can be derived into other parts of speech with the following suffixes:

| From... | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noun | Verb | Adjective or Determiner |

Adverb | ||

| To... | Noun | - | -pu | -rtu | -rtu |

| Verb | -ttya (to be X, temporarily) -ttyu (to do an X-like thing) |

- | -rtuttyu -isattyu (to become X) |

-rtuttyu | |

| Adjective or Determiner |

-rri | -pirri | - | -pirri | |

| Adverb | -kke | -pekke | -rte | - | |

Note that derived verbs can also be made causative.

- We-ni-pu-mupukku-ttya-nu mika setuki!

- 3SG.CAUS-1SG.ABS-PST-pig-be-DRPAC unwillingly witch

- The witch turned me into a pig!

Syntax

Word order

Standard word order is:

- Verb Phrase + Causative Noun Phrase + Ergative Noun Phrase + Absolutive Noun Phrase

Noun phrases are organized thus:

- Frontal Adjectives + Noun + Most Adjectives + Determiners + Relative Clause

The all-purpose negator is nu, which can grammatically be placed anywhere in a sentence, although the standard position is immediately after the verb phrase and any adverbs modifying the verb.

Frontal adjectives are a closed class of 16 adjectives that precede the noun. They tend to relate to unchangeable, essential traits of an object, animal, or person, but they are placed in front of the adjective regardless of context. They are:

| Adjective | English Translation |

|---|---|

| ari | dark |

| rrai | white |

| sanarra | thin |

| tarti | small |

| ttarai | magical |

| symui | tall |

| akkai | flat |

| smaki | curved |

| ekku | folded |

| marata | mortal |

| rasi | red |

| ityu | turquoise |

| teme | round |

| aratta | black |

| uiui | curved |

| urtuki | green |

The logic of the assignment of adjectives to the frontal or non-frontal class can seem arbitrary:

- ityu rasa

- turquoise car

- turquoise car

- rasa rsarni

- car blue

- blue car

- Na-∅-kkeu-kaki-rsirta-na rasi ke-rsirta.

- 1SG.ERG-3SG.ABS-see-can-face-DRPAC red 2SG.GEN-face

- I can see your red face (even if it is only blushing in the moment).

Conjunctions

The following conjunctions are used, and can be applied both to noun phrases and to clauses:

| Postposition | English Translation |

|---|---|

| hu | and |

| rsi | or (inclusive) |

| rsima | or (exclusive) |

| wa | but |

| rtti | because |

| kinya | after |

| kkawu | before |

| mamu | until |

| rraku | although |

| rnaku | when (for events in the past) |

| chaki | when (for events in the future, or in a general sense) |

Relative and independent clauses

Relative clauses, which are demarcated with the particle kku, are internally headed - grammatically capable of standing on their own.

- Hhi-symi-hhifai-rtima-na rtima-ma kku na-hhi-pu-hihu-nu?

- 3PL.ABS-exist-where-dumpling-DRPAC dumpling-PL that 1SG.ERG-3PL.ABS-PST-bake-DRPAC

- Where are the dumplings that I baked? (lit. "Where are the dumplings such that I baked them?")

Independent clauses are technically not possible in Rttirri. Instead, a dummy "noun" sa is incorporated into the main verb complex, and the verb complex in the clause is made into a gerund-like construct using the suffix -ppu. This eliminates the need for evidentiality particles on the clause, since nouns cannot have evidentiality. In the following example, a gerund is made the direct object of the verb "to say":

- Wa-∅-pu-rtiu-sa-na ∅-ppa-kau-ppu rra-kka.

- 3SG.ERG-3SG.ABS-PST-say-dummy-DRPAC 3SG.ABS-go-want-GER house-DAT

- She said that she wanted to go home. (lit. "She spoke her desire to go home.")

Quoted speech, however, requires no such nominalization. However, sa is still incorporated into the main verb complex.

- Wa-∅-pu-rtiu-sa-na, "Ni-ppa-kau-nu rra-kka!"

- 3SG.ERG-3SG.ABS-PST-say-dummy-DRPAC 1SG.ABS-go-want-DRPAC house-DAT

- She said, "I want to go home!"

Normally, relative and independent clauses are grammatically singular, but they can be pluralized to indicate an idea or utterance that is expressed repeatedly.

- Na-hhi-pu-nyarra-sa-na ke-ni-kka-kura-kapa-ppu!

- 1SG.ERG-3PL.ABS-PST-yell-dummy-DRPAC 2SG.ERG-1SG.ABS-IMP-kick-stop-GER

- I kept yelling at you to stop kicking me!

Sample text

Pipepi ("The Bushlark", 1958), a free-verse piece by the Rttirrian poet Sruwurtu Ukapi, who is credited with helping Rttirrian literature and poetry branch out from its long tradition of cynicism and darkness.

English Rttirri As I strode through the forest, Nitutasaifaityunu sasyakichatta, I found a bushlark sitting on the ground. pipepikka kku wukini mursuri. She cooed to greet me Puhirnunu sahaipuhhui nakka and lifted a limp wing to wave. hu weretumaki afnu michi. "So morose is the cry of the birds of this area," "Ttyasittyahirnupu kelime rreumanye rikeu," I remarked to myself. napukemisana. "Nay," she said! "I am happy. "Nu, nimarrattyana!" wapurtiusana. "My stomach cries for berries, "Amirsetini fraimahhui, but I can answer it with beetles. wa nikinene tyurrumarratye. "My lungs cry for exercise of the wings, Hhiamiwamini echauhhui makimanye, but I can answer them with a jog. wa nikinene mikikapurratye. My heart cries for a man or a friend Amirupana rnuhhui wa nyeppaihhui of my own kind, nakesyinye, anything for some pleasant conversation, rsi isipuhhui ttima eka, but I can answer it with you." wa nikinene kerratye."

See also

External links

- Rttirri on ConWorkShop