Katäfalsen

Introduction

Katäfalsen (pronunciation: [kɑˈtɑːfɑlsɛn]) is an apriori language, which is partially inspired by Basque, Hebrew and Latin. The aim was to construct a language with simple phonology along with unorthodox grammar and syntax. Katäfalsen is highly synthetic and features a free word order and ergative-absolutive alignment.

Phonology

Consonants

The consonant phonemes of Modern Katäfalsen are as follows:

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m /m/ |

n /n/ |

||||

| Stop | voiced | b /b/ |

d /d/ |

g /g/ |

||

| voiceless | p /p/ |

t /t/ |

k /k/ |

/ʔ/ | ||

| Fricative | f /f/ |

s /s/ |

h /x/ |

|||

| Approximant | r /ɹ/ |

j /j/ |

w /w/ |

|||

| Lateral approximant | l /l/ |

|||||

Vowels

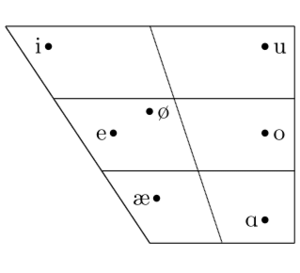

The vowel inventory of Katäfalsen is quite symmetrical as there are each three front, back, rounded and unrounded vowels.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |

| Close | i /i/ |

u /u/ | ||

| Mid | e /e/ |

ö /ø/ |

o /o/ | |

| Open | a /ɑ/ |

|||

The only vowel that distinguishes length is /ɑ/ contrasting phonemically with /ɑː/. The long vowel is represented by ⟨ä⟩. The sequences /ɑj/, /ɑw/, /ɑːj/ and /ɑːw/ are realised as diphthongs, while adjacent vowels are usually pronounced in hiatus.

Alphabet

The Latin alphabet used for Katäfalsen therefore contains the following letters. Uppercase letters are used for the first letter of a sentence and proper nouns.

| a | b | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | t | u | w | ö | ä |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | T | U | W | Ö | Ä |

Phonotactics

The syllable structure in Katäfalsen is CV(C), where C denotes a consonant and V a vowel. The glottal stop /ʔ/ is only allowed as syllable onset and only intervocalically in hiatus and word initially, i.e. after a break. This is not represented in the orthography.

Metathesis and epenthesis

Metathesis occurs in Katäfalsen when a suffix beginning with a consonant is added to a word. If the word ends with a vowel or diphthong, the morphemes are simply concatenated. The suffix -n, which creates female forms, is used for examples here.

ki + n → kin

kaj + n → kajn

However, if the word ends with a consonant instead, metathesis of this consonant and the preceding vowel occurs.

fales + n → falsen

In words that are either monosyllablic or feature a closed penultimate syllable (although very rare), an epenthetic vowel /ɑ/ is inserted.

sen + n → asnen

meslip + n → mesalpin

In addition, there is a class of words that ended with /ɑ/ but dropped the ending later. When taking suffixes, this vowel emerges again.

kat + n → katan instead of aktan

The epenthetic /ɑ/ occurs also before words which consist of a single consonant and disappears when the word takes suffixes beginning with a vowel.

aj

aj + an → jan

Vowel mutation

Old Katäfalsen had the additional phoneme /ħ/, which has disappeared in Modern Katäfalsen but has left still observable effects. We already know that the sequences /ɑj/, /ɑw/, /ɑːj/ and /ɑːw/ yield diphthongs. Moreover, whenever one of the phonemes /j/, /w/ and /ħ/ are syllable codae, they melt into the preceding vowel and cause the mutations summarised in the following table:

| Codae | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ħ/ | /j/ | /w/ | ||

| Nucleus | /ɑ/ | /ɑː/ | /ɑj/ | /ɑw/ |

| /e/ | /i/ | /i/ | /ø/ | |

| /i/ | /i/ | /i/ | /ø/ | |

| /o/ | /u/ | /ø/ | /u/ | |

| /u/ | /u/ | /ø/ | /u/ | |

| /ɑː/ | /ɑː/ | /ɑːj/ | /ɑːw/ | |

| /ø/ | /ø/ | |||

| /ɑj/ | /ɑːj/ | |||

| /ɑw/ | /ɑːw/ | |||

| /ɑːj/ | /ɑːj/ | |||

| /ɑːw/ | /ɑːw/ | |||

The last five syllable nuclei are never followed by /j/ and /w/ because they solely arise from the mutations above and complex syllable codae are forbidden. When a suffix beginning with a vowel is attached to a word ending with a mutated vowel, the mutation is usually undone.

tö + an → tojan

ami + an → amejan

As already mentioned, the class of words that ended with /ɑ/ in Old Katäfalsen behaves differently:

kat + an → kataan [kɑtɑʔɑn]

Double consonants CC were changed to ħC in Old Katäfalsen and also triggered vowel mutation later.

welal + n → wilan (via *wellan → *weħlan)

In other positions, Old Katäfalsen /ħ/ has merged with /ʔ/. Intervocalically, i.e. syllable initially after a vowel or diphthong, /ħ/ triggered mutation of the preceding vowel in dialects in which /ʔ/ and /ħ/ have both dropped completely.

*meħel → meel [meʔel] or dialectally miel [mi.el]

Stress

Katäfalsen features a dynamic stress. In contrast to compounds, the stress in simple words is always initial: katä and falsen are pronounced [ˈkɑtɑː] and [ˈfɑlsen]. In compounds, the stresses of words attached to the right are pulled to the previous syllable, thus the last syllable of the preceding word component. The last stressed syllable in a compound is the heaviest one. Therefore other stresses (including the initial stress on the first word component) are analysed as secondary stresses. If several stressed syllables are in a row, the rightmost is most dominant and the other ones are negligible. To come back to the example above, the compound Katäfalsen is finally pronounced [kɑˈtɑːfɑlsen] with the shifted stress of the second component being more dominant than the initial stress of the first one.

Further examples (the stressed syllables are in bold):

- kaj-sen: The stress of the last component is shifted to the previous syllable.

- kaj-sen-kat: The rightmost stressed syllable is most dominant.

- mesalpi-sedar: The initial syllable of the first component receives a secondary stress.

- agä-mesalpi-sedar: The stress on the second syllable is heavier than the one on the first syllable.

Phonetic remarks

The actual phonetic realisation of the phonemes depends a lot on the speaker's sociolect and also on the setting of speech. For example, a standard speaker would imitate a higher sociolect when talking to a dignitary and a lower one when talking to inferiors. Two extremes of the possible realisations are the religious and rural accents. The urban accent is considered standard.

Regarding vowels, the differences between the accents are marginal except for /ɑː/. /e/ and /o/ are consistently mid front unrounded and mid back rounded vowels, i.e. more precisely [e̞] and [o̞]. /i/ and /u/ tend to be slightly more open in rural accents ([ɪ] and [ʊ]) in contrast to [i] and [u] in religious accents, with the standard accent being somewhere in between. While /ɑ/ is quite consistently [ɑ], the length contrast to /ɑː/ has only survived in higher sociolects. In rural accents, both phonemes have merged into [ɑ]. On the other hand, the urban standard accent has fronted /ɑː/ to [æ]. /ø/ varies between the mid front rounded [ø̞] in higher and the mid central rounded [ɵ̞] in lower sociolects.

Phonemes that are pronouned in each accent exactly like their symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet are /b/, /d/, /g/, /m/, /n/, /j/, /w/ and /f/. The voiceless plosives /p/, /t/ and /k/ can be slightly aspirated in all accents. /h/ is usually the voiceless uvular fricative [χ]. /s/ is both in higher and urban sociolects [s] but [ʃ] in rural accents, which gives them a much softer sound. Being an alveolar approximant [ɹ] in the standard accent, /ɹ/ is tapped in rural as well as religious accents, i.e. [ɾ]. /l/ is usually velarised in religious accents ([ɫ]). An unmistakable indicator of the speaker's sociolect is the realisation of /ʔ/: In higher sociolects, the differentiation between /ʔ/ and /ħ/ is still prominent, with the pronunciation of the latter being [ħ]~[h]. Complete deletion of /ʔ/ occurs in lower sociolects, in this case disappearing /ħ/ triggers vowel mutation as mentioned in Vowel mutation.

Grammar

Nouns

Declension

Nouns are declined in four cases, which are found in a subordinate and a coordinate form each. The total number of cases is therefore eight. The case suffixes and their exemplary application to the noun pares (man) are given in the following table:

| Coordinate | Subordinate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suffix | Example | Suffix | Example | |

| Absolutive | ∅ | pares | *ħ | parsi |

| Dative | a | paresa | ä | paresä |

| Locative | e | parese | i | paresi |

| Ablative | o | pareso | u | paresu |

The glossing abbreviations used here are abs, dat, loc, abl, abs.sr, dat.sr, loc.sr and abl.sr. A selection of the most important usages of the cases locative, dative and ablative is given below. The subordinate forms will be gone into in the section Coordination and subordination.

- Dative: recipient or affected; where to; beneficiary

- Locative: place where, time when; accompaniment

- Ablative: where from; means or topic; cause, reason or value

Postpositions

Most Katäfalsen postposition can be treated as separate words and form (subordinate) compounds with the noun they refer to. The meaning of a postposition may change depending on its and the noun's case suffixes, while the noun always needs to be in the subordinate form. Examples:

- katätoni: katä-toni, mountain.abs.sr-middle.loc, 'in the middle of the mountain'

- parsitamali: parsi-tamali, man.abs.sr-thought.loc, 'regarding the man'

Pronouns

Katäfalsen has two personal pronouns, which like nouns do not differ in number intrinsically:

- aj I, we (from /j/ talking an epenthetic /ɑ/)

- aw you (from /w/ talking an epenthetic /ɑ/)

The subordinate forms are according the the rules given in Metathesis and epenthesis ajä and awä. The English third-person pronouns he, she, it, they are expressed by one of the demonstrative pronouns:

- ha and es refer to things or persons which are further specified in different ways:

- ha: The specification happens by describing the thing or person.

- es: The specification happens physically, i.e. there is a sensory perception.

- haj: Refers to things or persons close to the speaker.

- haw: Refers to things or persons away from the speaker but close to the listener.

- ä (from /ħ/ talking an epenthetic /ɑ/): Refers to things or persons away from both speaker and listener.

The subordinate form of ä is aä as ä is analysed as /ɑħ/ and has evolved /ɑħ/ + /ħ/ > /ɑħɑħ/ > /ɑʔɑː/.

Apparently, the phonemes /j/, /w/ and /ħ/ are connected to deixis in the first, second and third person. This recurs at ather words such as adverbs that feature deixis. For example, from the word mo place are derived:

- moje: mo-j-e, place-1-loc, 'here'

- mowe: mo-w-e, place-2-loc, 'at you'

- moe: mo-∅-e, place-3-loc, 'there'