Tinnermockaar

| ttỳnaamokkəər | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [/ˈtʼɪˀ.naː.mo.kʼɝː/] |

| Created by | – |

| Date | 2024 |

Isolate

| |

Tinnermockaar (natively ttỳnaamokkəər /ˈtʼɪˀ.naː.mo.kʼɝː/, which translates as 'the language') is an a priori conlang with an agglutinative grammar where most words are formed either by adding vowel-initial prefixes to CVC root to form a verb or verb-like element or by adding vowel-final suffixes to a root to form a nominal (noun or noun-like element). As a result, most Tinnermockaar words either start with a vowel and end in a consonant or vice-versa.

The language features a somewhat challenging phonology, including ejective stops, a three-way contrast in voicing and glottalized vowels based on Danish stød.

In addition to the Latin script orthography that will be used throughout this article, Tinnermockaar might be written in its own alphabet. The native orthography is moderately phonemic but it includes some etymological contrasts that are no longer observed in the spoken language.

Phonology

Consonants

The following table shows the consonant inventory for Tinnermockaar. Note that the rows and column in the table may indicate historical realizations that are no longer descriptive of the current realization of the respective consonant, as is the case for palatal 'stops' which have long shifted into affricates.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejective stop | tt //t̪ʼ/ | cc /tʼ/ | tts /tsʼ/ | kk /kʼ/ | |

| Plain stop | p /p/ | t /t̪/ | c /t/ | ts /ts/ | k /k/ |

| Partially voiced stop | b /b̥/ | d /d̪̥/ | đ /d̥/ | g /ɡ̊/ | |

| Voiced stop | bb /b/ | dd /d̼/ | đđ /d/ | ||

| Fortis pre-nasalized stop | mp /mp/ | nt /nt̪/ | nc /nt/ | ńk /ŋk/ | |

| Lenis pre-nasalized stop | mb /mb/ | nd /nd̼/ | nđ /nd/ | z /d̥z̥/ | ńg /ŋɡ/ |

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | ń /ŋ/ | ||

| Fricative | s /s̻/ | ś /s̺/ | x /ç/ | h /h/ | |

| Approximant | j /j/ | ||||

| Lateral | l /l/ |

Notes:

- Alveolar consonants, as well as the affricates tts and ts tend to have an apical realization.

- Velar consonants are allophonically uvular when following /u/ or /ʊ/.

- There are no traces of the language ever having an ejective labial stop. It should be noted however that many languages with ejectives also lack /pʼ/ (less acoustically distinctive from its plain counterpart than other ejective plosives), so such a gap is not unexpected.

- Unvoiced stops are very mildly aspirated.

- There is some variation in the VOT (voice onset time) for pre-nasalized stops, fortis might range from moderate aspiration to tenuis while lenis might range from almost tenuis to fully voiced.

- Pre-nasalized stops in final position might result in the allophonic nasalization of the preceding vowel. For instance, amb /amb/ might be realized as something closer to [ãb̥].

- The phoneme z /d̥z̥/ is listed under the lenis prenasalized series since it comes from a historical /ɲɟ/, but its current realization is closer to that of a partially voiced counterpart to ts.

- A fully voiced /ɡ/ was dropped except before front vowels, where it turns into /j/ instead.

- An (intrafictionally) earlier form of the language had a palatal series that has mostly shifted to other points of articulation.

- First, its partially voiced and fully voiced stops (presumably /\ɟ̊/ and /\ɟ/ ) merged with the corresponding velars /ɡ̊/ and /ɡ/ (before the latter was lost to further sound changes). This change seems to have happened early enough that the distinction is not attested even in the earliest forms of Tinnermockaar writing.

- Then historical /cʼ/ and /c/ shifted into /tsʼ/ and /ts/.

- Historical pre-nasalized /ɲc/ and /ɲɟ/ first experiences a similar shift, turning briefly into /nts/ and /ndz/ before a second shift turned them into pure affricates, with /nts/ merging with /ts/ while /ndz/ became z /d̥z̥/.

- The palatal nasal /ɲ/ turned into /j/. A later change would drop it before front vowels.

- A single coronal nasal n /n/ seems to have developed from a merger between a historical dental /n̪/ and an alveolar /n/. Orthographic evidence (in the native Tinnermockaar script) suggests that the two sounds might have first adopted a complementary distribution before being outright merged in a generally alveolar [n].

- It is unclear whether the language ever had a labial fricative (/f/ or /ɸ/), if it did, it must have long dropped or merged with another consonant (likely h).

- The 'dental' fricative s is a laminal /s̻/ while the 'alveolar' ś is an apical /s̺/, with speakers commonly pronounced it as a postalveolar [ʃ], especially in word-final position.

- The 'palatal' fricative x /ç/ often shifts to [x] before back vowels.

- The 'velar' fricative h is realized either as a glottal fricative /h/ or outright dropped (especially between non-high vowels).

- A glottal stop [ʔ] and a rhotic alveolar approximant [ɹ] might occur as allophonic pronunciations for glottalized and rhotacized vowels, respectively.

The native orthography in the Tinnermockaar script still makes some distinctions that are not preserved in the spoken language:

- Distinction between /ts/ from historical /c/ and historical /ɲc/ (transcribed as nts).

- Distinction between /j/ (and null onsets from a historical dropped /j/) from historical /ɲ/ (transcribed as ñ) and historical /ɡ/ (transcribed as gg).

- Two characters that might have once corresponded to a historical dental /n̪/ (sometimes transcribed as n̈) and a historical alveolar /n/ (transcribed as n) now generally present a complementary distribution, with dental n̈ usually being found before back vowels although multiple exceptions to this rule can be found.

Vowels

Tinnermockaar has the following vocalic inventory:

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i /i/ | u /u/ | |

| Upper | y /ɪ/ | v /ʊ/ | |

| Mid | e /e/, [e̞] | o /o/ [o̞] | |

| Lower | ə /ɜ/ | ||

| Low | a /a/, [ä] |

Note that the vowels y and v are considered to be 'front' and 'back' (respectively) despite actually having a more centralized realization.

All vowels can be short or long (indicated by doubling the vowel).

Five diphthongs are allowed, all of them falling: ae /ae̯/, av /aʊ̯/, ey /eɪ̯/, ov /oʊ̯/ and əi /ɜi̯/. No length distinctions are observed on diphthongs.

All diphthongs and all non-high vowels (short or long) might be glotalized, with a realization similar to Danish stød. This is marked with a grave accent diacritic on the (last) letter as in v̀ for /ʊˀ/, aà for /aːˀ/ and əì for /ɜi̯ˀ/.

The vowels a, e, o v, y and ə (short or long) and the diphthongs ae, av and əi might be rhotacized, marked with an \<r\> after the vowel: ar for /a˞ /, yyr for /ɪ˞ ː/, avr for /aʊ̯˞ /. Since the hook diacritic used in IPA to mark rhoticity is often hard to read if not completely absent in most fonts, these will be notated with a /ɹ̆/ as in /ʊːɹ̆/ for vvr rather than /ʊ˞ː/.

Only a short ə is allowed to be simultaneously rhotacized and glotalized: ə̀r for /ɜˀɹ̆/. Historically, v̀r /ʊˀɹ̆/ was also allowed, although it later merged with ə̀r (the distinction is preserved in the native orthography, though).

Some speakers (particularly those in the peripheries of the language, in contact with non-native speakers who might struggle with rhoticity and glottalization) might pronounce rhotacized vowels as plain vowels followed by a rhotic such as [ɹ] or [ɾ] and pronounce glotalized vowels as plain vowels followed by a glottal stop [ʔ].

Phonotactics

Tinnermockaar allows for (C)V(V)(C) syllables, which is to say, an optional onset composed of a single consonant, a mandatory nucleus composed of a vowel or diphthong (possibly bearing glottalization or rhoticity) and an optional coda consonant.

Notice that prenasalized stops and affricates are counted as single consonants and that rhoticity and glottalization are not regarded as adding codae, thus a syllable such as ttsə̀rmp'' /tsʼɜˀɹ̆mp/ conforms to the allowed CVC pattern.

Codae are only allowed in word-final position. As a result, consonant clusters are not allowed to occur within a word. Vowel clusters (ie sequences of onset-less syllables) are allowed freely, with a hyphen being used to separate syllables in these cases as in enav̀-aakvvr ('they heated it').

Ejectives are realized as plain stops in word-final position (such that att and at would both be pronounced /at/) while fully voiced stops are realized as partially-voiced ones (abb and ab would both be pronounced /ab̥/). The original pronunciation surfaces when a suffix is added.

Although no phonotactical rule requires it, the fact that Tinnermockaar morphology often revolves around CVC roots which take either vowel initial prefixes or vowel final suffixes makes it so a vast majority of Tinnermockaar words either begin in a vowel and end in a consonant (V...C) or vice-versa (C...V). These two possibilities also relate to Tinnermockaar parts of speech, with verbals being overwhelmingly vowel-initial (and consonant-final) whereas nominals tend to be consonant-initial (and vowel-final).

Suprasegmentals

The language does not have phonemic tones nor stress. Word tend to be stressed on their first syllable.

Morphology

Tinnermockaar constructs most of its words out of roots, sequences which cannot be used as words on their own. A Tinnermockaar root typically has a CVC structure such as √ttỳn /tʼɪˀ.n/ for 'speaking', although a limited number of roots are composed of a single consonant C, some can only be analyzed as having a CVCVC structure and a considerable number omit one or more consonants, possibly due to the historical loss of certain consonants.

Roots often have verb-like main meanings (as seen previously with √ttỳn, 'speaking') but they might also be mainly noun-like as with the root √havp 'copper'. Regardless of this, most roots have the potential to be used both in noun-like and verb-like derivations, as evidenced by ttỳnaamokkə (language, a noun derived from √ttỳn) or eerbbihavp for 'they are made of copper' (a verb derived from √havp).

It is also relatively common for roots to have different forms or have small 'families' of roots differing only in their vowel or some suprasegmental aspect thereof (such as root pairs differing only in vowel length or glottalization). These differences can mostly be attributed to irregular sound change and seldom show any consistent patterns.

These roots (which can be termed 'primary roots') are often extended into 'secondary roots' by adding a prefix, usually of the form CV-. These prefixes often relate to some vague form of locative meaning such as ma- roughly corresponding to 'around', transforming the core meaning of the root √ńvm related to movement to √mańvm for with meanings of 'roaming' or 'walking around'. It should be noted, however, that the semantic derivation resulting from these affixes can be fairly unpredictable. For instance, applying the same prefix to √ttỳn (speaking) yields √mattỳn with a rough meaning of 'fame' (presumably because people around the famous person would speak about them) while applying it to √nin (to breathe) results in √manin meaning 'to sneeze' in a rather unclear derivation. These derivational prefixes are remarkably similar to the 'preverbs' found in Indo-European languages (such as the 'for' in 'forgive'), although the resulting meanings of might differ.

Tinnermockaar words are derived through the addition of affixes (prefixes or suffixes) to these roots (be they primary or secondary roots). For the most part, these derivations follow one of two patterns corresponding to a main division in the language: verbals (mostly derived with vowel-initial prefixes) and nominals (exclusively derived with vowel-final suffixes).

Note: that the morphological classes I refer to as 'verbals' and 'nominals' in Tinnermockaar might not correspond to other usages of those words in linguistics (such as Chomsky's notion of 'nominals'), they are just meant as a convenient term for this conlang in particular.

Verbals

Tinnermockaar verbals mostly correspond to verbs describing a past, generic or habitual state; present and future-tense verbs are handled instead through a construction involving an auxiliary verbal a nominal instead. Since Tinnermockaar's equivalents to adjectives are verb-like, they are often handled as verbals as wells.

Verbals usually present the following structure:

| Component | Optional / Mandatory | Default (if not explicit) |

|---|---|---|

| Mood marker | Optional | Realis |

| Subject/theme agreement | Mandatory | - |

| Aspect marker | Optional | Atelic |

| Secondary root prefix | Optional | - |

| Root | Mandatory | - |

| Voice marker | Optional | Active voice |

The fact that most (not all though!) mood and agreement markers begin in a vowel and that most roots and all voice markers end in a consonant makes it so that verbals are overwhelmingly vowel-initial and consonant-final. In fact, certain words of dubious classification are considered verbals in Tinnermockaar tradition solely on the basis that they have this phonetic structure, as in the genitive particle əl.

Mood

Tinnermockaar verbs might carry a mood prefix for non-realis usages, this is to say, when describing a situation which is (or was) not an actual fact in the present or past. Non-realis moods include:

- Interrogative (INT, prefix kkaah-) - required for polar questions.

- Potential (POT, prefix ax-) - indicates a possibility (like English 'can' or 'may').

- Interrogative-potential (INT.POT, prefix àkkaah-) - asks bout whether something might happen (or have happened).

- Optative (OPT, prefix eyt-) - used for wishes, hopes.

- Jussive (JUS, prefix əcaant-) - indicates a mandatory state (like English 'must' or some usages of 'shall').

- Irrealis (IRR, prefix ind-) - other hypothetical situations, conditionals, etc.

For instance

| Mood | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Realis | Enav̀ccəń. | They hunted it |

| Interrogative | Kkaahenav̀ccəń ? | Did they hunt it? |

| Potential | Axenav̀ccəń. | They might have hunted it |

| Interrogative-potential | Àkkaahenav̀ccəń ? | Could they have hunted it? |

| Optative | Eytenav̀ccəń ! | Let's hope they hunted it |

| Jussive | Əcaantenav̀ccəń. | They must (are required to) have hunted it |

| Irrealis | Indenav̀ccəń ... | (If) they hunted it... |

The jussive mood is not to be confused with the imperative (commands issued to the listener), which are formed through a separate construction.

Subject and theme agreement

Tinnermockaar has what is known as polypersonal agreement, with transitive verbs (verbs featuring both a subject and an object) being mandatorily marked for both arguments, while intransitive verbs (thus with a single argument, also known as 'subject' in English but referred to as 'theme' in Tinnermockaar) taking a different set of prefixes to mark their one argument. Voice suffixes, as discussed later on, might be used to allow transitive verbs to behave as intransitive ones and vice versa.

Both forms of argument agreement indicate the grammatical person of the argument as well as some other distinctions such as animacy and number for third person referents. The following cases are contrasted:

- First person exclusive (1.EXCL) - usually refers to the speaker (I, me) but it might also be used to refer to 'exclusive we' (the speaker and others, not including the listener).

- First person inclusive (1.INCL) - 'inclusive we', the speaker, the listener and, possibly, others.

- Second person (2) - the listener or listeners (you) and possibly others.

- Animate third person singular (3s.ANIM) - a human (or a being that acts like a human, such as a personified god) other than the speaker and listener; corresponding to English 'he', 'she' or singular 'they'.

- Animate third person plural (3p.ANIM) - more than one person.

- Inanimate third person singular (3s.INAN) - one object/animal or a group of uncountable objects (such as 'the sand'); 'it'.

- Inanimate third person plural (3p.INAN) - more than one distinct objects or animals. Not distinguished from 3s.INAN for transitive subjects.

Further distinctions in number (such as contrasting 1.EXCL as used for singular 'I' or for plural 'we [me and others]') might be made by including an overt pronoun (as discussed within the section for nominals) but that is relatively uncommon.

Definiteness is contrasted for third person inanimate themes, contrasting sentences such as enav̀kàccəń ('they hunted it', where the animal that was hunted refers to a known individual) and eenəkàccəń ('they hunted one', where the animal that was some previously undefined individual).

In the following tables, prefixes for each combination are given with the subject being indicated by the column and the theme or direct object by the row. For suffixes whose Tinnermockaar script spelling is not predictable, the appropriate spelling is provided between brackets.

| Subject (columns): | None (Intransitive) | 1.EXCL | 1.INCL | 2 | 3s.ANIM | 3p.ANIM | 3.INAN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.EXCL | əńee- | - | - | tsəńỳ- | ème- | aàmy- | àńav- |

| 1.INCL | ańyỳ- | - | - | - | èmyỳ- | aàmyỳ- | ə̀rńyỳ- |

| 2 | iì- | ijee- (iñee-) | - | - | ənce- (aàntse-) | aàtse- (aàntse-) | ə̀rttsə- |

| 3s.ANIM | i- | ayńè- | yyrńè- | ətsè- | əmba- | aàmba- | àśe- |

| 3p.ANIM | əmà- | əńkà- | yyrnkà- | ətsà- (əntsà-) | əmpeè- | aàmpa- | əśaà- (vśaà-) |

| 3s.INAN.DEF | oo- | avńga- | əənga- | ətsə- | ovr- | enav̀- | av̀- |

| 3s.INAN.INDF | vr- | əńvr- | əərńvr- | vtsə- | ey- | eenə- | ə̀r- (v̀r-) |

| 3p.INAN.DEF | eer- | əńeer- | yrńeer- | ətseer- | ə-eer (əggeer-) | aàńga- | eèr- |

| 3p.INAN.INDF | eer- | əńyỳ- | yrńyỳ- | ətsyỳ- | əńka- | aàńka- | eèr- |

Bear in mind that the reflexive and reciprocal voices (explained in the Voices section below) are required for actions where the subject and theme coincide.

Citation forms for verbs

While in English the citation form of a verb (ie the form usually listed in dictionaries and used to refer to the verb) is the infinitive, the preferred citation form for Tinnermockaar verbs is a verbal with no optional affixes presenting agreement prefixes for third person arguments. These prefixes depend on whether the verb is transitive or intransitive and on whether its expected arguments are more likely to be humans or inanimate objects.

Intransitive verbs which are more likely to have a human theme take the 3s.ANIM prefix i- as in iđđun (they slept) for 'to sleep'; if the theme is judged more likely to be non-human, the 3s.INAN prefix oo- is used instead as in oobbihavp (it is made of cooper) for 'to be made of cooper'. Cases where both a human or a non-human theme are possible vary, by they tend towards the former as in ideìkvvr (they are hot) for 'to be hot', although an inanimate citation form oodeìkvvr (it is hot) could occasionally be used should the context make it clear it is meant to apply to a non-human.

A similar situation occurs for transitive verbs, which take a prefix corresponding to third person singular arguments whose animacy was determined by their most likely referents although with a clear bias towards preferring animate subjects and inanimate topics. As a result, the citation form of most transitive verbs tends to bear the ey- prefix (animate subject, inanimate theme), even though əmba- (animate subject and theme), ə̀r- (inanimate subject and theme) and, rarely, àśe- (inanimate subject, animate theme) are also possible options:

| Intransitive | Animate subject | Inanimate subject | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animate theme | i- | əmba- | àśe- |

| Inanimate theme | oo- | ey- | ə̀r- |

Aspect

Tinnermockaar contrasts three aspects, indicated though suffixes between the agreement marks and the main stem (root and secondary root prefixes).

By default, verbs take the unmarked atelic (ATEL) aspect which indicates an event without a specific endpoint. For instance, atelic iccəńàk, 'he hunted', indicates that the action is conceptualized as being a prolonged state (as implied in 'they were out hunting') without a specific goal that would mark its endpoint.

On the other hand, the prefix kà marks a verb as telic (TEL), which indicates an action with a defined endpoint. For example, telic ikàccəńàk, which we might also translate as 'he hunted', actually indicates that there was a goal that was accomplished and which marked an endpoint for the action (in the example, the hunter probably chased after one particular game).

There is a commonly used rule of thumb in linguistics for telling apart whether a phrase is telic or atelic: if the action can be given with a time frame (as in 'within an hour), it is telic (the endpoint is pinpointed as being achieved within the timeframe) while an atelic phrase will usually require a time-span instead such as 'for an hour.

Meanwhile the prefix zi- is used to indicate an inchoative (INCH) aspect, which marks the beginning of a state. Thus iziccəńàk corresponds to 'they started hunting'.

Voice

Verbals corresponding to transitive verbs might take a suffix to indicate a change in grammatical voice, which is to say, an unexpected behavior in the argument of the transitive verb.

By default, such verbs are found in their active voice which includes a distinct subject and an object. For instance, enav̀kàccəń ('they hunted it') is marked as having a human third person subject and a definite non-human third person object.

A reflexive voice marker -as is required to indicate that the subject and object coincide, that the subject does the action to itself. The resulting verb is only marked for its theme, as in ooccəńas for 'it hunted itself'.

The reciprocal or mutual marker -ubbàm has a similar usage except that it indicates that individuals within a group do something to each other (but not to themselves). For instance, əmàccəńubbàm translates to 'they hunted each other'. This would indicate that there were at least two parties, one hunting the other and vice-versa, as opposed to reflexive əmàccəńas 'they hunted themselves'. Informally, however, it would be relatively common for native Tinnermockaar speakers themselves to use both forms interchangeable, indicating that this distinction is seemingly falling out of use.

For verbals with a distinct subject and object, the passive and antipassive voices allow for one of those arguments to be dropped. Passive -it converts a transitive verb into a syntactically intransitive one with the original object as its theme as in ookàccəńit for 'it was hunted', '[someone] hunted it'. Conversely, antipassive -àk allows the subject alone to to be marked, also becoming the theme of a syntactically intransitive verb as in ikàccəńàk for 'they hunted [something]'.

Verbals corresponding to an intransitive verb might take the causative marker -eeś which turns them into a transitive verb where the subject influences the theme to reach the state normally marked by the intransitive verb. For instance, oodeìkvvrm 'it was hot' might be used to derive enav̀deìkvvrmeeś, 'they made it hot'. It should be noted, however, that many intransitive verbs have a transitive counterpart that will usually be preferred to a causative form; thus to specify an agent responsible for the state of being hot indicated by oodeìkvvrm a separate transitive verb, enav̀-aakvvr, 'they heated it'.

The attributive verbal an

The word an is a verb-like element with two main uses: - Acting as a copula verb (like English 'to be') for equaling two nominals, as in 'X is Y'. - Being used as a particle to introduce relative clauses.

Unlike ordinary Tinnermockaar verbs, an presents an irregular paradigm. It might only be conjugated for mood (taking the usual mood prefixes) and for argument agreement (through completely irregular forms). Despite the fact that an takes two arguments when used as a copula verb, its conjugation only references the grammatical person for single argument, without any number or animacy distinctions for the third person:

| Person | Form of an |

|---|---|

| 1.EXCL | əńaàn (spelled as əhanàn in Tinnermockaar script) |

| 1.INCL | amyńan |

| 2 | tsaan |

| 3 | an |

In addition to not being permitted to take aspect and voice markers, an might not appear in present or future tense constructions; its tense is unless a time adverb is added.

See the sections on noun copula and relatives under the Syntax header for more information.

Nominals

Tinnermockaar nominals include nouns, certain verb forms such gerunds used in present-tense constructions as well as adverbs, determiners and, arguably, even pronouns. Tinnermockaar's own (intrafictional) tradition would also include conjunctions and prepositions under this category.

The structure of nominals is not as rigid as that of verbals, but it's often composed of the following elements:

| Component | Optional / Mandatory | Default (if not present) |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary root prefix | Optional | - |

| Root | Mandatory | - |

| Derivational suffix | Mandatory Multiple suffixes may be used |

- |

| Definiteness marking | Optional | Indefinite |

| Number marking | Optional | Singular or collective (depending on the noun) |

| Case marking | Optional | Absolutive |

Nominals are typically consonant-initial (as are most roots, primary or secondary) and are very commonly vowel-final although exceptions to this are not uncommon.

The citation form of a nominal is the one without definiteness, number and case markers.

Derivational suffixes

Tinnermockaar nominals require at least one derivational suffix to be added to the primary or secondary root. These suffixes typically hint at the intended meaning of the nominal, although some derivations might be unexpected.

The language has a wide array of derivational suffixes including:

- -aa - a noun denoting an action or an event, as in ccəńaa, 'hunt'.

- -avr - groups, as in bankumbavr, 'crowd'.

- -eemə - materials, as in havpeemə, 'copper'.

- -eer - Animals or plants, as in ddebbeer for 'bird' (from ooddebb, 'to fly')

- -i - an animate actor, as in ccəńi, 'hunter'.

- -ò - a patient of a concluded transitive action, as in ccəńò (game, prey that has been hunted).

- -v - a person who is characterized by an intransitive verb as in mindv, 'visitor' (from imind, 'to arrive').

Verb nominals: participles and gerunds

Certain derivational suffixes are used for nominals related to verbs. This includes two forms dubbed 'participles' used in relative clauses (the active participle -yrbba and the passive participle -àkka) and a number of gerunds used for present and future tense constructions whose derivational suffixes encode the verb's voice:

- -eynər - active voice gerund (also used for reciprocal voice).

- -eeccər - passive voice gerund (also used for reflexive voice).

- -aettsər - antipassive voice gerund.

Verbal stems might also form nominals using a gerundive suffix -ae which indicates purpose and which might be required to be used along modal verbs.

Definiteness

Nominals corresponding to nouns may be made definite by applying the following sound changes on their final vowel:

- Non-glottalized short vowels are lengthened.

- The resulting vowel or diphthong is replaced by a 'rhotic counterpart' when one exists, as shown below:

| Original | Definite | Original | Definite | Original | Definite | Original | Definite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a, aa | əər | à | ə̀r | aà | aà | ar, aar | əər |

| e, ee | yyr | è | è | eè | eè | er, eer | eer |

| i, ii | ii | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| o, oo | vvr | ò | ə̀r | oò | oò | or, oor | oor |

| u, uu | uu | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| v, vv | vvr | v̀ | ə̀r | vv̀ | vv̀ | vr, vvr | vvr |

| y, yy | yyr | ỳ | ỳ | yỳ | yỳ | yr, yyr | yyr |

| ə, əə | əər | ə̀ | ə̀r | əə̀ | əə̀ | ər, əər | əər |

| ae | aer | aè | aè | - | - | aer | aer |

| av | avr | av̀ | av̀ | - | - | avr | avr |

| ey | yyr | eỳ | eỳ | - | - | - | - |

| ov | vvr | ov̀ | ov̀ | - | - | - | - |

| əi | əir | əì | əì | - | - | əir | əir |

Number

By default, Tinnermockaar nouns might be either singular (referring to a single object) or collective (referring to a group of non-distinct objects or to an uncountable substance); this is a lexical property that cannot be determined from affixes alone.

For non-collective nouns (singular by default), three additional grammatical numbers can be formed through suffixes:

- Partitive (suffix -dər) - indicates a group of elements drawn from a larger group.

- Paucal (suffix -bà) - indicates a small number of elements.

- Plural (suffix -ga) - indicates a large number of elements.

The distinction between paucal and plural is a fuzzy one, groups below 3 or 4 objects will generally be marked as paucal while groups above 5 or 6 will usually be marked as plural but the paucal vs plural distinction might also reflect a contrast with expectations. For instance, if a mythological creature had 4 eyes, those might be referred in plural to highlight the anomaly, while a garrison of 10 soldiers where several dozen would be expected might be referred to in the paucal. The partitive number, on the other hand, does not distinguish whether the number of elements is high or low, it only focuses on the fact that only some of the elements (in an otherwise unstated group) are relevant.

Plural marking is mandatory, even when a numeral is given.

Collective nouns, meanwhile, may also take the partitive suffix (-dər) to indicate fraction of the collective or substance, or a singulative (-ceèt if word final, -ceè if followed by a case suffix) for indicating a single element drawn from the collective (not applicable to substances).

Finally, nouns of either type (but more usually non-collective ones) might take a negative suffix xoòt (or -xoò if followed by a case suffix) indicating a null quantity.

As an example, consider ccəńi ('hunter'), a countable noun, which might take the following suffixes:

| Number | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | ccəńi | a hunter |

| Partitive | ccəńidər | some of the hunters |

| Paucal | ccəńibà | some hunters |

| Plural | ccəńiga | many hunters |

| Negative | ccəńixoòt | no hunters |

Meanwhile, collective nouns might be exemplified by bankumbavr (crowd) and havpeemə (copper) as follows:

| Number | Example 1 | Translation | Example 2 | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collective | bankumbavr | a crowd | havpeemə | (some) copper |

| Singulative | bankumbavrceèt | a person in the crowd | - | - |

| Partitive | bankumbavrdər | part of the crowd | havpeemədər | part of the copper |

| Negative | bankumbavrxoòt | no crowd | havpeeməxoòt | no copper |

Cases

Tinnermockaar nouns inflect for three cases: absolutive (unmarked), marked nominative (or 'ergative', suffix -cə) and benefactive (suffix -ngeè). Unlike other suffixes, case markers are separated from the nominal with a hyphen in Latin script orthography, so the benefactive form of ccəńi will be spelled as ccəńi-ngeè rather than ccəńingeè.

The ergative case, which perhaps could be better deemed as 'marked nominative' case, is optionally required for subjects. Its marker, -cə, is generally found in subjects of transitive verbs although it is often left out for subjects occurring in a fronted position (moved to the beginning of the sentence for emphasis).

More unusually, the suffix might -cə may be occasionally found in intransitive subjects for verbs with which also have an oblique argument and in present-tense constructions (where the primary verb gerund could also be considered to act as an oblique argument to the auxiliary).

Pronouns seldom bear the -cə marker, regardless of the situation.

The benefactive case marker, -ńgeè, may be used to indicate an argument other than a subject or theme that benefits or has commanded the action. This case is also used for indirect objects in verbs such as eynđ ('to give').

All other roles are expressed with the unmarked absolutive case, possibly in combination with prepositions such as locative byr ('in').

Pronouns

Pronouns are used sparingly in Tinnermockaar as they are made largely redundant due to the polypersonal agreement in verbs. They will commonly occur for oblique roles that wouldn't be marked otherwise, though.

Since Tinnermockaar pronouns work largely in the same way as nouns, they might be inflected for number, allowing for finer distinctions than the ones shown in verb prefixes. For instance, while first person exclusive markers don't distinguish between singular "I, me" and plural "we ~ me and others", the overt pronoun haańà can specify the argument as singular, while the addition of number-marking suffixes can yield more precise plural meanings such as haańàdər (only some of us), haańàbà (me and a few others), haańàga (me and many others) and haańàxoòt (none of us). It should be noted, however, that it's usually more idiomatic for a Tinnermockaar speaker to drop pronouns.

Tinnermockaar personal pronouns are as follows:

| Singular | (Dual) | Paucal | Plural | Partitive | Negative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First person exclusive (me [and others]) |

haańa | haańabà | haańaga | haańadər | haańàxoòt | |

| First person inclusive (you and me [and others]) |

hàmyy | hàmyybà | hàmyyga | hàmyydər | hàmyyxoòt | |

| Second person (you [and others]) |

tsidi | tsidibà | tsidiga | tsididər | tsidixoòt | |

| Third person animate (he/she/they) |

hee-i | heerbà | heerga | heerdər | heerxoòt | |

| Third person inanimate (it/they) |

ccy | ccybà | ccyga | ccydər | ccyxoòt |

Number marking is largely regular aside from unmarked 'singular' hàmyy actually referring to two people ('you and me') and the third person animate pronoun using different roots for singular hee-i (which doesn't accept any number markings) and plural *heer (which requires a number marker).

Other than that, Tinnermockaar pronouns only differ from nouns in that they hardly ever take the 'ergative' -cə marker.

Syntax

Tinnermockaar is a somewhat typologically ambiguous language. As intransitive and transitive verbs differ considerably in their paradigm (as far as argument marking is concerned), it is hard to unambiguously classify it as having a nominative-accusative or an ergative-absolutive alignment, morphological clues suggest a tendency towards the latter although it can be noted that what could be interpreted as an ergative case marker might occasionally be used for intransitive subjects, a feature more in line with a nominative-accusative language. While this sort of typologically ambiguity is sometimes found in natural languages, it might not be out of line for one to question the naturalisticness of this conlang.

Word order

Tinnermockaar has a fairly flexible word order, although sentences default towards verb-initial orders, mainly VSO (verb-subject-object). This might be altered to place emphasis, with SVO word orders highlighting the subject and VOS (or, more rarely, OVS) word orders highlighting subjects (a practice referred to as 'subject fronting' which usually also involves dropping case makers for this argument). Oblique complements such as adverbial phrases or benefactives are typically found at the end of the sentence, although they might be placed directly after the verb for greater emphasis.

Arguments can be dropped, although transitive verbs will be marked for both their arguments unless given in a valency-decreasing voice (reflexive, passive, antipassive). An entire sentence might consist of just a verb, with all its arguments being left implicit.

Verbs might be expressed as a single verbal (for generic or past-tense statements) or as an auxiliary verbal followed by a nominal form of the verb (for present or future tense).

Modifiers, including the equivalent to relative phrases, come after the element they modify.

Present and future tense constructions

As previously mentioned, by default a Tinnermockaar verb will refer either to an event in the past or to a generic or habitual statement (this two interpretations usually being distinguished by context alone, although time adverbs could be used to lift any resulting ambiguity).

In order to speak of a specific event taking place in the present, the auxiliary verb iś must be used, followed by a gerund of the intended verb, typically ending in -eynər. The auxiliary takes all the markings related to mood, subject/theme agreement and aspect. Voice marking might involve both the auxiliary and the gerund, as shown in the following table:

| Voice | Voice marker in the auxiliary | Gerund |

|---|---|---|

| Active | None (active as default) | Active (-eynər) |

| Reflexive | Reflexive (-as) | Passive (-eeccər) |

| Reciprocal | Reciprocal (-ubbàm) | Active (-eynər) |

| Passive | None (marked only in the gerund) | Passive (-eeccər) |

| Antipassive | None (marked only in the gerund) | Antipassive (-aettsər) |

| Causative | Reciprocal (-ééś) | Active (-eynər) |

For instance, eenəccəń might be interpreted as 'they hunted' or 'they hunt (regularly)'; adverbs such as mimbyr, 'yesterday' or kkaè, 'often' may be given to further specify one of those interpretations. In order to indicate a current event such as 'they are hunting', the auxiliary verb construction with iś will be needed, resulting in eenəś ccəńeynər, with iś displaying the agreement markers for subject and object while the primary verb is found as an active gerund.

It should be noted that the verb iś is slightly irregular: telic forms are given as -kəəs instead of the expected -kaś.

Future tense can be expressed through a similar construction using the auxiliary verb imind (which might also be used on its own as a verb meaning 'to arrive') with the difference that the auxiliary must be marked as having an irrealis mood. For instance, we might find indeenəmind ccəńeynər for 'they will hunt'.

It is worth noticing, however, that many usages which might be covered by a future tense in other languages might be expressed using moods in Tinnermockaar, such as the potential mood to indicate an unrealized possibility or the optative to indicate a desired future state.

Negatives

Tinnermockaar utilizes two negation strategies depending on whether the arguments of the verb are included in the sentence.

If either the subject or the object of the verb are present in the sentence (aside from being referenced by verbal prefixes), then negation is most commonly marked by using the negative 'number' suffix on the relevant noun. For instance, the negation of əmbaś jaacceynər mpànvvr-cə nacv (the man sees a woman) might be given as any of the following:

- Əmbaś jaacceynər mpànvvrxoò-cə nacv (negating the subject, literally 'No man sees a woman')

- Əmbaś jaacceynər mpànvvr-cə nacvxoòt (negating the object, literally 'The man sees no woman')

Colloquially, negating both elements (still keeping a negative meaning) is also an option, although this wording might be perceived as non-standard.

- Əmbaś jaacceynər mpànvvrxoò-cə nacvxoòt.

Since the negative marker -xoò(t) takes the position of number markers, it might get in the way of expressing certain finer distinctions or imply an unwanted degree of totality in the negation. For instance the wording əmbaś jaacceynər mpànvvr-cə nacvxoòt (~ the man sees no woman) may be taken to imply that that the subject is not seeing any woman so it wouldn't be appropriate to indicate that the man doesn't see a woman in particular (possibly being able to see others) .

An alternative method involves using the negative particle xav which must always precede the primary verb of the sentence - before the verbal if there is no auxiliary and between the auxiliary and the gerund otherwise:

- Əmbaś xav jaacceynər mpànvvr-cə nacv (negating the verb, literally The man doesn't see a woman').

This second strategy is required for verbs lacking a explicit subject or object. It should be noted that using xav and avoiding explicit pronouns is by far a more common strategy than using explicit pronouns that might take the -xoò(t) prefix, although the latter option might be occasionally be used for emphasis:

- Xav ijeekajaacc (I didn't see you, most common wording with negation using xav and implicit pronouns)

- Ijeekajaacc haańàxoòt (''I didn't see you, explicit negated first person pronoun for emphasis)

- Ijeekajaacc tsidixoòt (I didn't see you, explicit negated first person pronoun for emphasis)

If both negation strategies are combined (something seldom found), the result is typically interpreted as a positive:

- Əmbaś xav jaacceynər nacvxoòt mpànvvr-cə (negating the verb and the object, understood as meaning 'No woman isn't seen by the man').

Interrogatives

Polar questions (those that can be answered in English with 'yes' or 'no) are formed in the same way as declarative sentences other than requiring the interrogative mood prefix kkaah-. To continue with the prior example, the polar question 'Does the man see the woman?' may be translated as Kkaahəmbaś jaacceynər mpànvvr-cə nacv?.

Other questions, such as the ones formed in English using the 'wh-words' (like 'who' or 'what') generally do not require the interrogative prefix kkaah-. Interrogative pronouns like đvv (what, used for inanimates) and đey (who, used for animates) behave like regular nominals and, unlike personal pronouns, inflect for case a usual. For instance, we might have:

- Əmbaś jaacceynər đey-cə nacv? (Who sees a woman?)

- Əmbaś jaacceynər mpànvvr-cə đey? (Who does the man see?)

Tinnermockaar does not have a 'wh-fronting' rule like English requiring interrogative pronouns to be moved to the beginning of the sentence, although Tinnermockaar's flexible word order does allows this order, which comes out as somewhat more emphatic. As usual, the ergative marker -cə is typically omitted for a fronted subject.

- Đey əmbaś jaacceynər nacv? (Who sees a woman?)

The interrogative mood marker might be combined with an interrogative pronoun in order to make a wh-question about an uncertain event. For instance Kkaahəmbaś đey-cə nacvvr? might be translated as 'Does anyone see the woman? If so, who?'. Such combined questions would expect either a negative answer (Xav əmbaś ~ No one does) or the answer to the question word (Mpànvvr ~ the man).

Yes/no answers

Polar questions are typically answered by repeating the verb (adjusting argument agreement markers if needed) or the auxilliary, preceded by xav if negative.

For instance, the expected answers for Kkaatsəńỳś jaacceynər?, 'Do you see me?' will be either Ijeeś (I do [see you]) or Xav ijeeś (I do not [see you]).

Imperatives

Imperatives (sentences given an order to a second person) are formed using an auxiliary verb (ittsat, root -ttsat) and gerunds, in a construction not disimilar from those used for expressing the present and future tense.

Imperatives are generally considered polite for Tinnermockaar speakers, speakers might issue direct commands rather than requiring some workaround construction for politeness like English usually does (compare the blunt sounding "Do it!" with gentler formulae such as "Could you do it?" or "Would you mind doing it?").

Orders where the second person takes the role of a subject (be it of a transitive or intransitive verb) require the active gerund, as in Iìttsat mindeynər for 'Come!' or Ətsèttsat jaacceynər mpànvvr! for 'See the man!'.

Imperatives where the second person is required to take the role of a transitive direct object are formed in the same way but using the passive gerund. Note, however, that the auxiliary verb will still be conjugated as a transitive verb in this case. For instance, we might have Əncettsat jaacceeccər mpànvvr-cə! for 'Be seen by the man!', with the auxiliary taking the prefix ənce- marking it as a transitive verb with a singular third person animate subject and a second person object.

It should be observed that passive imperatives still represent a command the second person must actively seek to accomplish. The previous example, Əncettsat jaacceeccər mpànvvr-cə!, implies that the listener must to do something to ensure the man sees them, rather than placing responsibility on the man (the latter might indicated instead using a jussive mood construction).

Antipassive gerunds are required for orders with an antipassive meaning. In this case, the auxiliary verb is conjugated as an intransitive verb and does not require the -àk marker. For instance, Iìttsat ccəńaettsər! translates to 'Hunt (something)!'.

Negative imperatives are formed by preceding the auxiliary verb with the negative particle xav (rather than placing it between the auxiliary and the main verb as in present/future-tense constructions). Thus, Xav iìttsat ccəńaettsər! becomes 'Do not hunt!'.

It is worth remembering that many imperative-like constructions might be formed through verbal mood markers instead, including jussive for indicating a mandatory state (but not one that necessarily requires the second person to take an action towards) and the optative mood for wishes. Compare the following:

- Əncettsat jaacceeccər mpànvvr-cə! (using a passive imperative) - 'Be seen by the man!' (orders the speaker to ensure that the other person sees them).

- Əcaantəncejaacc mpànvvr-cə! (using a jussive form of əncejaacc, 'he sees you') - 'The man must see you!' (the requirement is not necessarily the listener's responsibility, pressumably both parties will be required to comply).

- Iìttsat ccəńaettsər! - 'Hunt something!' (a command, using an imperative construction).

- Eytiìccəńàk! - 'May you hunt something!' (a wish, using the optative voice).

Possessives

Possession is marked with the particle əl which is placed between the possession and the possessor as in havpeeməərdər əl mpànvvr for 'some of the copper (havpeeməərdər) of the man (mpànvvr)' or 'some of the man's copper'.

The same pattern might be used alongside pronouns, such as əl tsidi for 'your(s)'.

Noun copula

Sentences where a noun is equated with another, such as 'X is Y' are typically expressed using the verbal an, whose highly irregular conjugation was showcased earlier on.

Although an acts as a verb in this construction, it might only take mood and person prefixes (no aspect, voice or tense marking). An constructions are not necessarily taken to be habitual or past-tense as sentences with bare verbal usually are; its interpretation in regards to tense is usually left to context although time adverbs might be added if necessary.

If X and Y are both nouns, the sentence is given as an X Y. For instance, 'the man is a hunter' might be given as an mpànvvr ccəńi (ATTR man\\DEF hunter) although, depending on the context, the sentence might also be interpreted as 'the man was a hunter' or similar variations.

Pronouns are usually omitted, being marked instead in the conjugation of an. It should be noted, however, that an, nearly all other Tinnermockaar verbs, fails to distinguish number and animacy in the third person. Even though number is unmarked in the verb, it will be marked on the noun that appears as the remaining argument in the copula, so, for instance, the following sentences with ccəńiga, the plural form of ccəńi (hunter), will necessarily have a plural interpretation:

- Əńaàn ccəńiga. - We (exclusive) are hunters.

- Amyńan ccəńiga. - We (inclusive) are hunters.

- Tsaan ccəńiga. - You all are hunters.

- An ccəńiga. - They are hunters.

Negatives are formed as usual with the particle xav: as in xav əńaàn ccəń for 'I am not a hunter'.

Interrogatives also work as usual, with the interrogative mood prefix kkaah- being required for polar questions.

- Kkaahan ccəńiga? - Were they hunters?

- Tsaan đey? - Who are you?

Imperatives for the copula are rare but they might be formed by using ittsat (usually an auxiliary) on its own:

- Iìttsat ccańi! - Be a hunter!

Relative clauses

The attributive verbal an is also used for Tinnermockaar's equivalent to relative clauses, sharing the same limitations such as being unable to state tense and aspect. It should be noted that, should the need arise, these limitations can be circumvented by saying the phrases independently. For instance, English 'The man who the woman saw is hunting' would generally be expressed through a construction that could be roughly interpreted as 'the seen-by-the-woman man is hunting', which fails to capture explicitly whether the woman is observing him in the present or whether she saw him in the past; should that distinction prove crucial to the discourse speakers might describe the situation through two separate phrases instead: 'The woman saw the man. / He is hunting.'.

Relative constructions where the inner sentence is comprised of a copula between nouns are formed simply by following the antecedent with an and the nominal to which it is equated: mpànvvr an ccəńi for 'the man who is a hunter' (or 'who was a hunter').

Otherwise, an must be followed by a participle. The choice of participle depends on the syntactic role of the antecedent within the relative clause, using active participles (suffix -yrbba) when it appears as a subject or the passive participle (suffix -àkka) when it appears as a direct object (other roles are not supported and require the speaker to use separate clauses instead). Examples include:

- mpànvvr an mindyrbba - the man who arrived / who is arriving / who is going to arrive

- mpànvvr an ccəńyrbba - the man who hunted / is hunting / is going to hunt

- mpànvvr an ccəńàkka - the man who was hunted / is hunted / will be hunted

Other arguments can be introduced to the relative clause using əl for a subject (as if it was a possessive) or ttə for a direct object:

- mpànvvr an ccəńyrbba ttə ahuulə - the man who hunted a wolf

- mpànvvr an ccəńàkka əl ahuulə - the man who a wolf hunted

Relative clauses are negated by placing xav before an: mpànvvr xav an mindyrbba for 'the man who didn't arrive'.

Alternative relative clause construction

Modern Tinnermockaar seems to be in the process of developing an alternate construction for relative clauses where the attributive an is not followed by a participle but by a full verb as in mpànvvr an ovrccəń for 'the man who hunts it' rather than standard mpànvvr an ccəńyrbba (~ the hunting man).

This construction, however, is still perceived as non-standard and is often relegated to informal situations.

Numerals

Tinnermockaar has a fairly simple base-10 numeration system. Numerals follow the noun to which they apply, which must still bear grammatical number suffixes as usual, as in singular mpànv pè for 'one man', paucal mpànvbà cynə for 'three men' and plural mpànvga bbov for 'eight men'.

There is no numeral for 'zero' as null quantities are expressed through the 'negative' grammatical number instead: mpànvxoòt for 'no men' or 'zero men'.

Numbers from 1 to 10 are expressed as follows:

| Number | Tinnemockaar |

|---|---|

| 1 | pè |

| 2 | ccer |

| 3 | cynə |

| 4 | pyyr |

| 5 | zynə |

| 6 | bbav |

| 7 | kkuu |

| 8 | bbov |

| 9 | hav |

| 10 | hati |

Multiples of ten are formed by adding the 'tens' digit after hati as in hati ccer (ten-two) for 20. The units can then be stated by adding the conjunction aa (and) and the appropriate digit, as in hati hav aa cynə (ten-nine and three) for 93. The same pattern applies to larger numbers with attè for 'hundreds' and gumbə for 'thousands'. For example, the number 1234 will be given as gumbə aa attè ccer aa hati cynə aa pyyr, literally 'thousand and hundreds-two and tens-three and four'.

Tinnermockaar script

Tinnermockaar's native writing system is an alphabet, written horizontally from left to right. The script has some featural elements. Dried palm leaves are its most common writing medium, often being tied together into books.

Most letters are based on incomplete circular outlines formed by a 'bow' which leaves an opening near the bottom of the glyph for letters corresponding to a consonant or near the top for letters for vowels and diphthongs.

Many glyphs come in pairs consisting a 'soft' character where all elements are written within the bow and a 'hard' character where one or more strokes stretch beyond the bow. Paired soft and hard glyphs generally correspond to phonemes with similar articular, such as unvoiced stops and their ejective counterparts or plain vowels and their glottalized counterparts.

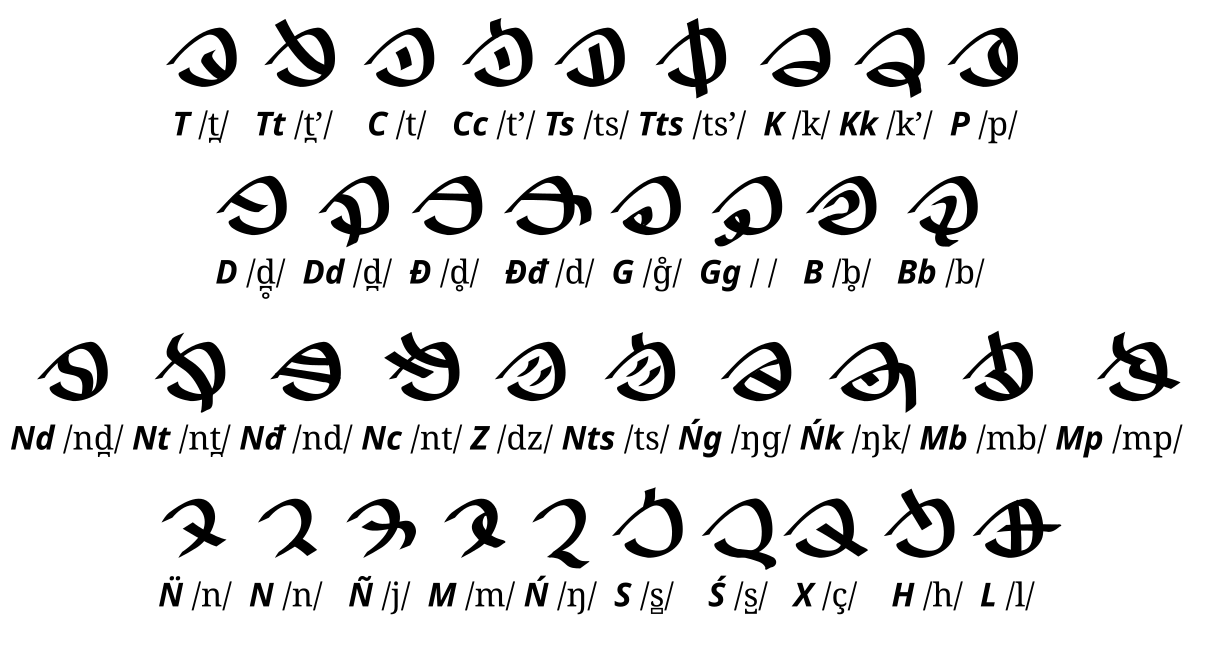

Consonants

The Tinnermockaar script includes 36 consonant letters, traditionally listed in the following order:

As mentioned within the Phonology section, the Tinnermockaar script retains a number of distinctions that have been lost in the spoken language, resulting in a slightly non-phonetic orthography. Irregularities to keep in mind include:

- The consonant /ts/ (romanized as ts) might be written as either Ts or Nts depending on the word's etymology.

- Null onsets corresponding to a historical /ɡ/ are written with an initial Gg.

- The glide /j/ is written as Gg or as Ñ depending on etymological considerations.

- The consonant /n/ is written as N̈ before back vowels and in all forms of the attributive an, otherwise /n/ is written as N.

- A small number of words have irregular spellings reflecting earlier pronunciations such as the word àtte (one hundred) retaining an irregularly lost h and thus being spelled as *hàtte.

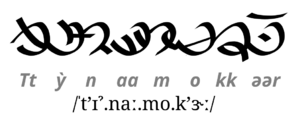

Vowels

Each non-rhotic vowel or diphthong is represented by one of the following 38 letters, contrasting length and glottalization (or lack thereof):

Rhotic vowels are written as their non-rhotic counterparts with a bar below, as seen in the final character of name ttỳnaamokkəər (Tinnermockaar, the native name of the language) which can be identified as an Əə character bearing the rhoticity marker above/

As shown in the example, Tinnermockaar letters are often written without any space between one another, although exceptions may be made depending on the shape of the intervening letters (as seen above with the N and the Aa). It is most common for writers not to conjoin letters belonging to separate words, although this rule is by no means universal.

Aside from a few unpredictable irregular spellings (such as the pronoun heergà, 'they', which is spelled as heeñiga) written vowels match pronunciation with one exception: the glottal rhotic vowel /ɜˀɹ̆/ might be written either as ə̀r (matching its romanization) or as v̀r, reflecting a historical /ʊˀɹ̆/ pronunciation that has since merged with ə̀r.

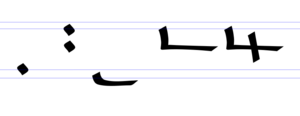

Punctuation

Tinnermockaar punctuation is rather limited when compared to that used in the Latin script and also considerably more flexible in its usage. It includes the following marks:

| Punctuation | Usage |

|---|---|

| Dot below | Used to separate words. Optional but fairly common. Often omitted after an (attributive particle/verb) and əl (possessive particle). |

| Two dots | Described intrafictionally as 'marking the end of an idea', this mark is generally used to separate sentences although some authors might omit it between sentences which share a topic. |

| Underline | A small underline under the first character of a word is used as an 'emphasis marker' which might be used for any elements that may be considered as particularly 'important' or worthy of deference within a passage. Personal names referring to others are always marked with this punctuation sign as a way to show respect towards them (regardless of whether their role within the text bears much relevance or not). By contrast, the writer's own name (or that of the patron in whose name a scribe composes a text) never bears this marker as doing so could be seen as inappropriately self-aggrandizing. No special considerations are held for marking pronouns, however. |

| End of section | This marker replaces the 'two dots' sign at the end of a group of related sentences. Although particulars about its usage might vary from author to author, it could be thought of as a paragraph separator. The 'end of section' mark implies that the text will be continued (possibly on the a different page). |

| End of text | Replaces the 'end of section' mark after the final section of a text. |

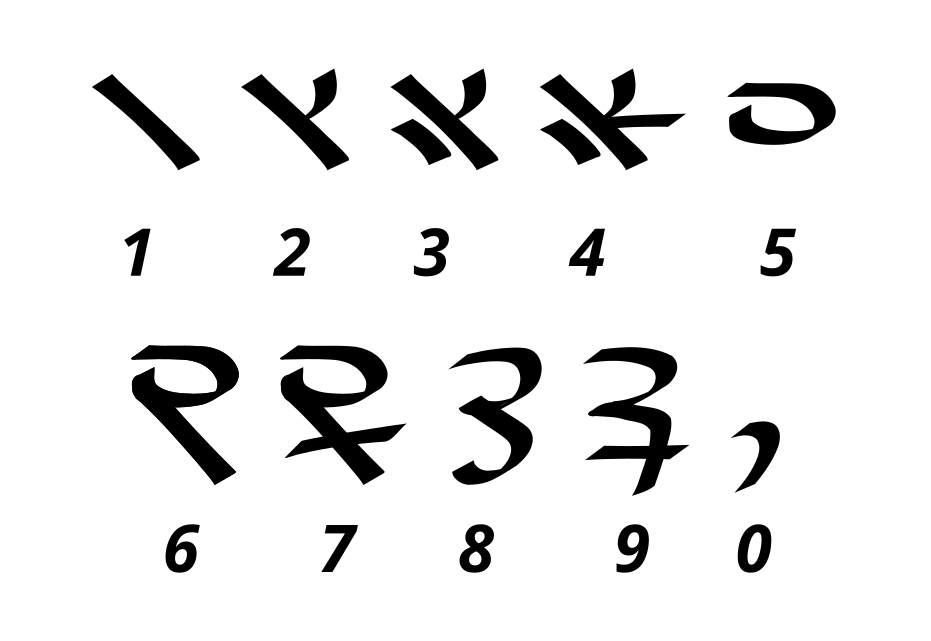

Numerals in the Tinnermockaar script

Numbers in written Tinnermockaar are typically expressed through a set of numerals which, much as our own Arabic numerals (0123456789) employ a positional base-10 notation with larger digits written on the left. This means that Arabic numerals might be converted to and from Tinnermockaar simply by replacing the glyphs for each digits.