Natalician

This article is private. The author requests that you do not make changes to this project without approval. By all means, please help fix spelling, grammar and organisation problems, thank you. |

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

| Natalician | |

|---|---|

| Nataledhi | |

Flag of the Natalician Republic | |

| Pronunciation | [na.ta.le.di] |

| Created by | Hazer |

| Date | 2021 |

| Native to | Natalicia; Firenia and the Kontamchian Islands |

| Ethnicity | Natales |

| Native speakers | 37,123,487 (2021) |

Tinarian

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Natalicia, Firenia, Budernie, Nirania, Kannamie |

Recognised minority language in | Espidon, Amarania (Dogostania) |

| Regulated by | The Natalician Academic Council for Linguistics |

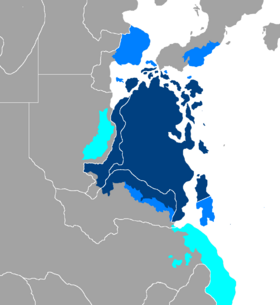

A map showing the distribution of (native and non-native) speakers of Natalician in Tinaria. Dark blue is native, light blue is secondary language speaker, and cyan is minorities. | |

Natalician (/nəˈtɑlɪʃən/ or /ˌnɑteɪˈlɪʃ.ən/; endonym: Nataledhi [na.ta.le.di] or Natal Rettive /na.tal re.tːive/) is a North Kasenian language mainly spoken in Central East Tinaria, primarily in Natalicia, Firenia and North-East Nirania. Outside of Natalica, it is recognized as an official language in Budernie, Nirania, Kannamie and as a minority language in East Espidon and the Dogostanian community in Eastern Amarania. Natalician is closely related to other North Kasenian languages such as Espidan and Niranian.

Modern Natalician gradually developed from Old Natalician, which in turn developed from an extinct unnamed language spoken by the Natalo-Kesperian tribes. Today, Natalician is one of the most important languages in the world, and is the most spoken Kasenian language, both natively and as an additional language. About 65 million people speak Natalician worldwide, 37 of which are natives.

Natalician is a language characterised by the lack of cases, the absence of genders, nearly no irregularity and a systematic grammar and an orthography with no digraphs, dipthongs or anything of the like, making it such a straightforward language to read and learn.

History

The earliest traces of the Natalician language date as far back as the year 334, with a much different vocabulary and grammar as that of the modern descandant, sub-dividing the Natalician language's history into 3 timelines - Classic Natalician (334 - 1203), Old Natalician (1203 - 1540) and Modern Natalician (1540 - present). The language is estimated to be 1687 years old as of 2021.

Classic Natalician

Also known as the Poetic Natalician or the Natalo-Kesperian Language, the only recorded evidences of the earliest traces of the language are found in ancient poetries and old writings on recovered artifacts. These evidences however are deemed not enough by the NACL to be considered a valid or complete written evidence of the Natalo-Kesperian spoken language, as illiteracy was dominant in the pre-Killisic era and the chosen vocabulary choice is said to be too formal. Classic Natalician's vocabulary has many direct elements from the early Proto-North-Kasenian language which was later ambolished due to the migratory era, culture clashes and the increase of loanwords.

There is no known documents for Classic Natalician that have survived. No known evidence of the development of the language during the primary era have been found.

Old Natalician

Rëširi ëgsös nör på tånåka if kelševi wezzen fölsi sos.

“The people have the right to write and say what they please.”

When the Killistic era entered, the Natale tribes have recieved access to knowledge brought by the proclaimed king of the Natales, Ribel Zömeri. It was the era where literacy skyrocketed in the newly born and united Natale monarchy [1203 - 1834], and printed evidence of the Natalician language have surfaced and bloomed.

The first recorded book containing written evidence comes from the book "Natåltïå kočåculaï orūnza" (Natalician Guide Book) by late author Ulun Cilesli Irkete, written and published in year 1210. Following that have come multiple documents that have been preserved through generations and found as artifacts in the Natalician Grand Museum of Literature and Artifacts in Celicia.

Many scholars of history and literature have claimed that Classic and Old Natalician are the same language, but lack of evidence weakened the claims. Scholar Iček Friktinäm quotes: "Old Natalician may be the result of intervention of new local loanwords and the varieties of dialects may have caused a deviation of Kasenian roots from the standard spoken Natalician at that time."

Old Natalician features a drastically different grammar and vocabulary from that of the Natalician of today, the most notable difference is vowel harmony and cases. The old language features 4 vohel harmony types and 3 grammatical cases: Nominative, Accusative and Genetive. The different suffixes and verb conjugation are majorly notable differences aswell.

Modern Natalician

Äg čan vizih zifekev if savekilivev ensei ťenałr nameš čan özev.

“Our history is filled with rich stories and leaders.”

During the beginning of the decline of the monarchy,

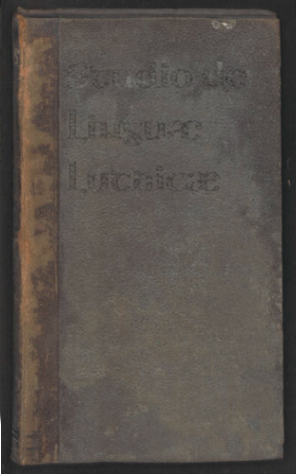

De Studio Linguæ Luthicæ

De Studio Linguæ Luthicæ (English: On Study of the Luthic Language) often referred to as simply the Luthicæ (/lʌˈθiˌki, lʌθˈaɪˌki/), is a book by Þiudareico Bianchi that expounds Luthic grammar. The Luthicæ is written in Latin and comprises two volumes, and was first published on 9 September 1657.

Book 1, De grammatica

Book 1, subtitled De grammatica (On grammar) concerns fundamental grammar features present in Luthic. It opens a collection of examples and Luthic–Latin diglot lemmata.

Book 2, De orthographia

Book 2, subtitled De orthographia (On orthography), is an exposition of the many vernacular orthographies Luthic had, and eventual suggestions for a universal orthography.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | |||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s θ | ʃ | h | ||||

| voiced | v | z ð | ʒ | ʁ | |||||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡ʃ | |||||||

| voiceless | d͡ʒ | ||||||||

| Approximant | semivowel | j | w | ||||||

| lateral | l | ʎ | |||||||

| Gorgia Toscana | (ɣ˕) | ||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||||

| Trill | ʀ | ||||||||

Consonant Harmony

Natalician orthography reflects voice sandhi voicing, a form of consonant mutation with two consonants that meet, and the second is voiced and the first is unvoiced. The first unvoiced consonant [p t f ʃ t͡ʃ θ k s] is voiced to [b d v ʒ d͡ʒ ð ɡ z], but the orthography remains unchanged. This usually does not include load words.

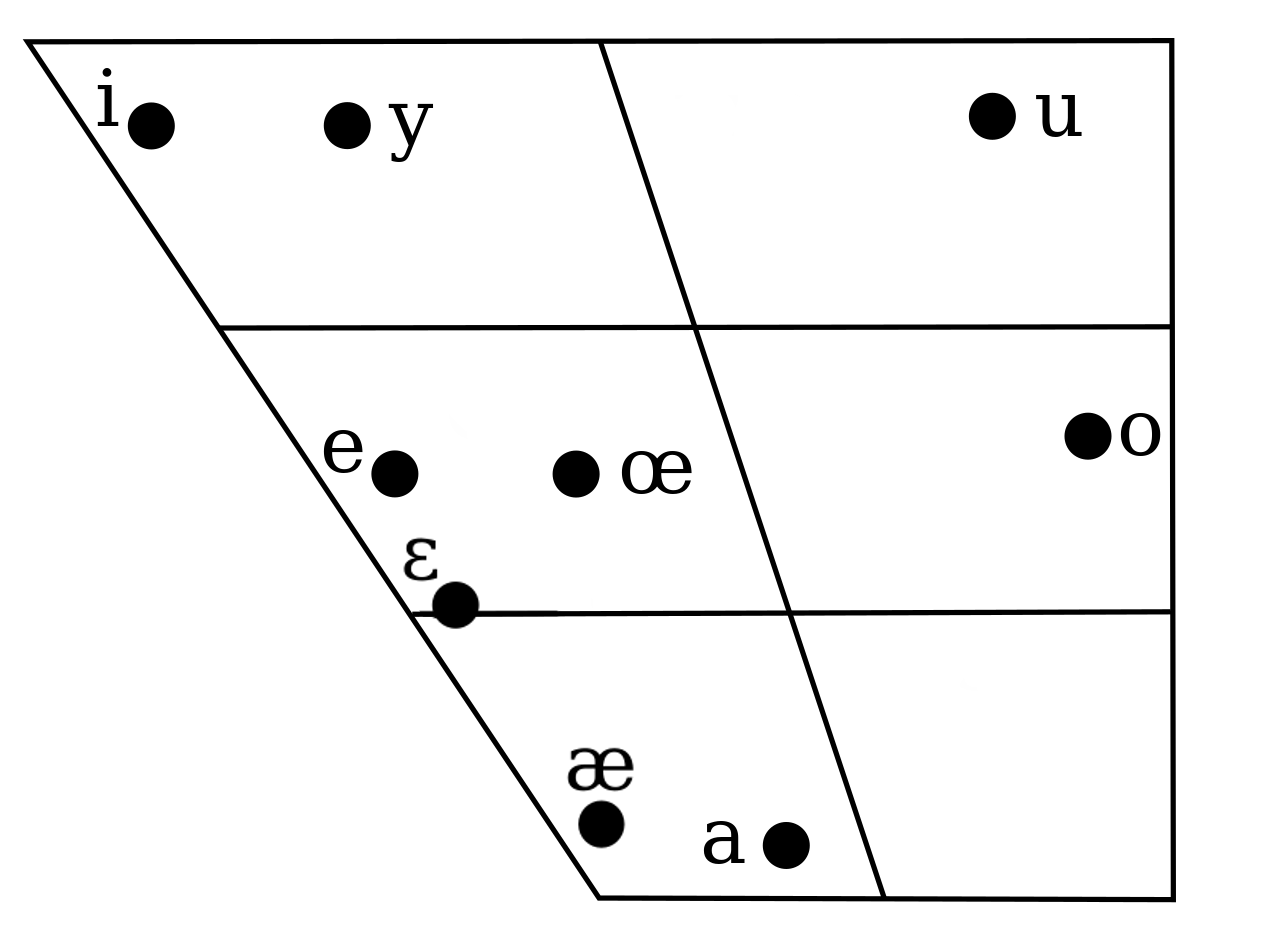

Vowels

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |

| Close | i | y | u | |

| Near-open | æ | |||

| Open | e | œ | a | o |

The vowels of the Natalician language are, in their alphabetical order, ⟨a⟩, ⟨ä⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨ü⟩.

The Natalician vowel system can be considered as being three-dimensional, where vowels are characterised by how and where they are articulated focusing on three key features: front and back, rounded and unrounded and vowel height.

Notes

- When the vowels /i/, /u/ precede or succeed another vowel, they become /j/, /w/ respectively. If both vowels meet one another, only the /i/ will transform into a /j/ which the /u/ remains unchanged.

- The only diphthong in the whole language is the Object second person singular Ou (You), pronounced /uː/.

Vowel harmony

| Natalician Vowel Harmony | Front Vowels | Back Vowels | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |||||||

| Vowel | ä | e | i | ö | ü | a | o | u | ||

| Type Ĕ (Backness) | e | o | ||||||||

| Type Ĭ (Backness + Rounding) | i | ü | a | u | ||||||

The principle of vowel harmony

- If the first vowel of a word is a back vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a back vowel; if the first is a front vowel, any subsequent vowel is also a front vowel.

- If the first vowel is unrounded, so too are subsequent vowels.

The second and third rules minimize muscular effort during speech. More specifically, they are related to the phenomenon of labial assimilation: If the lips are rounded (a process that requires muscular effort) for the first vowel they may stay rounded for subsequent vowels. If they are unrounded for the first vowel, the speaker does not make the additional muscular effort to round them subsequently.

Grammatical affixes have "a chameleon-like quality" and obey one of the following patterns of vowel harmony:

- Twofold (-e/-o): The article, for example, is -(v)e after front vowels and -(v)o after back vowels.

- Fourfold (-i/-a/-ü/-u): The verb infinitive suffix, for example, is -i or -a after unrounded vowels (front or back respectively); and -ü or -u after the corresponding rounded vowels.

- Type & 'and': The adjectival passive voice suffix, for example, is -t&t, the & being the same vowel as the previous one.

Practically, the twofold pattern (usually referred to as the type Ĕ) means that in the environment where the vowel in the word stem is formed in the front of the mouth, the suffix will take the e form, while if it is formed in the back it will take the o form. The fourfold pattern (also called the type Ĭ) accounts for rounding as well as for front/back. The type & pattern is the reppetition of the same last vowel. The following examples, based on the nominal suffix -zĭk, illustrate the principles of type Ĭ vowel harmony in practice: Čikelzik ("Wellness"), Okzuk ("Knowledge"), Ianzak ("Food"), Nörzük ("Living").

Exceptions to vowel harmony

These are four word-classes that are exceptions to the rules of vowel harmony:

- Native, non-compound words, e.g. Ela "then", Čela "drink", Äga "by"

- Native compound words, e.g. Pawez "for what"

- Foreign words, e.g. many English loanwords such as Sertifikäht (certificate), Hospital (hospital), Komphuter (computer)

- Invariable prefixes / suffixes:

| Invariable prefix or suffix | Natalician example | Meaning in English | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| –tüs | iantüs | "eating" | From ian "eat" |

| –(v)iš | üčiš | "exit" | From üč "leave." |

| öz- | özhaša | "to return" | From haša "to come" |

| gik- | gikögültüt | "unwanted" | From ögültüt "wanted" |

Note

- A native compound does not obey vowel harmony: Ras+cezil ("city center"—a place name)

- Loanwords also disobeys vowel harmony: Kofi ("Coffee")

- Every grammatical prefix disobeys the vowel harmony aswell.

Orthography

Alphabet

Natalician has a straightforward orthography, meaning very regular spelling with no diphthong or digraph or anything of the sort. In linguistic terms, the writing system is a phonemic orthography. The following are exceptions:

- The letter that is called Girbit El ("Silent L"), written ⟨Ł⟩ in Natalician orthography, represents vowel lengthening. It never occurs at the beginning of a word or a syllable, always follows a vowel and always preceeds a consonant. The vowel that preceeds it is lengthened.

- The Object second person singular Ou is the only digraph in the entire language, making the sound of /uː/.

- The letter ⟨H⟩ in Natalician orthography represents two sounds: The /h/ sound, and the /j/ sound. If the letter ⟨H⟩ is located at the beginning of the word, it takes the /h/ sound, otherwise it takes the /j/ sound. (e.g. Hiloh /hi.loj/ "Hello", Konah /ko.naj/ "Beautiful", Haz /haz/ "This")

Standard Natalician alphabet

| Letter | Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Aa | a [a] | /a/ |

| Ää | ä [æ] | /æ/ |

| Bb | be [be] | /b/ |

| Cc | ce [d͡ʒe] | /d͡ʒ/ |

| Čč, | če [t͡ʃe] | /t͡ʃ/ |

| Dd | de [de] | /d/ |

| Ďď | ďe [ðe] | /ð/ |

| Ee | e [e] | /ɛ/, /e/ |

| Ff | ef [ɛf] | /f/ |

| Gg | ge [ɡ] | /g/ |

| Hh | ha [ha] | /h/, /j/ |

| Ii | i [i] | /i/, /j/ |

| Jj | je [ʒe] | /ʒ/ |

| Kk | ka [ka] | /k/ |

| Ll | el [ɛl] | /l/ |

| Łł | girbit el [gir.bit ɛl] | /ː/ |

| Mm | em [ɛm] | /m/ |

| Nn | en [ɛn] | /n/ |

| Oo | o [o] | /o/ |

| Öö | ö [œ] | /œ/ |

| Pp | pe [pe] | /p/ |

| Rr | er [r] | /r/ |

| Řř | eř [ɛʁ] | /ʁ/ |

| Ss | es [s] | /s/ |

| Šš | eš [ɛʃ] | /ʃ/ |

| Tt | te [te] | /t/ |

| Ťť | ťe [e] | /θ/ |

| Uu | u [u] | /u/ |

| Üü | ü [y] | /y/ |

| Vv | ve [ve] | /v/ |

| Ww | w [wa] | /w/ |

| Zz | ze [ze] | /z/ |

Luthic has geminate, or double, consonants, which are distinguished by length and intensity. Length is distinctive for all consonants except for /d͡z/, /ʎ/, /ɲ/, which are always geminate when between vowels, and /z/, which is always single. Geminate plosive and affricates are realised as lengthened closures. Geminate fricatives, nasals, and /l/ are realised as lengthened continuants. When triggered by Gorgia Toscana, voiceless fricatives are always constrictive, but voiced fricatives are not very constrictive and often closer to approximants.

Phonology

There is a maximum of 8 oral vowels, 5 nasal vowels, 2 semivowels and 35 consonants; though some varieties of the language have fewer phonemes. Gothic, Frankish, northern Suebi, Langobardic, Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish (Roman Gaul) influences were highly absorbed into the local Vulgar Latin dialect. An early form of Luthic was already spoken in the Ostrogothic Kingdom during Theodoric’s reign and by the year 600 Luthic had already become the vernacular of Ravenna. Luthic developed in the region of the former Ostrogothic capital of Ravenna, from Late Latin dialects and Vulgar Latin. As Theodoric emerged as the new ruler of Italy, he upheld a Roman legal administration and scholarly culture while promoting a major building program across Italy, his cultural and architectural attention to Ravenna led to a most conserved dialect, resulting in modern Luthic.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | (ŋʷ) | ||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | kʷ | ||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ɡʷ | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s θ | ʃ | ç | (x) | h | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ʁ | |||||

| Affricate | voiceless | (p͡f) | t͡s (t͡θ) | t͡ʃ | |||||

| voiceless | d͡z | d͡ʒ | |||||||

| Approximant | semivowel | j | w | ||||||

| lateral | l | ʎ | |||||||

| Gorgia Toscana | (ʋ) | (ð̞) | (ɣ˕) | ||||||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||||

| Trill | ʀ | ||||||||

Notes

- Nasals:

- /n/ is laminal alveolar [n̻].

- /ɲ/ is alveolo-palatal, always geminate when intervocalic.

- /ŋ/ has a labio-velar allophone [ŋʷ] before labio-velar plosives.

- Plosives:

- /p/, /pʰ/ and /b/ are purely labial.

- /t/, /tʰ/ and /d/ are laminal dentialveolar [t̻, t̻ʰ, d̻].

- /k/ and /ɡ/ are pre-velar [k̟, ɡ̟] before /i, e, ɛ, j/.

- /kʷ/ and /ɡʷ/ are palato-labialised [kᶣ, ɡᶣ] before /i, e, ɛ, j/.

- Affricates:

- /p͡f/ is bilabial–labiodental and is only found as a common allophone.

- /t͡θ/ is dental and is only found as a common allophone.

- /t͡s/ and /d͡z/ are dentalised laminal alveolar [t̻͡s̪, d̻͡z̪].

- /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are strongly labialised palato-alveolar [t͡ʃʷ, d͡ʒʷ].

- Fricatives:

- /f/ and /v/ are labiodental.

- /θ/ is dental.

- /s/ and /z/ are laminal alveolar [s̻, z̻].

- /ʃ/ is strongly labialised palato-alveolar [ʃʷ].

- /x/ is velar, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /ʁ/ is uvular, but in anlaut is in free variation with [h].

- /h/ is glottal, but is in free variation with [x ~ ʁ], /h/ is palatal [ç] nearby /i, e, ɛ, j/.

- Approximants, flap, trill and laterals:

- /ʋ/ is labiodental, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /ð̞/ is dental, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /j/ and /w/ are always geminate when intervocalic.

- /ɾ/ is alveolar [ɾ].

- /ɣ˕/ is velar, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /ʀ/ is uvular [ʀ], but is in free variation with alveolar [r].

- /l/ is laminal alveolar [l̻].

- /ʎ/ is alveolo-palatal, always geminate when intervocalic.

Historical phonology

The phonological system of the Luthic language underwent many changes during the period of its existence. These included the palatalisation of velar consonants in many positions and subsequent lenitions. A number of phonological processes affected Luthic in the period before the earliest documentation. The processes took place chronologically in roughly the order described below (with uncertainty in ordering as noted).

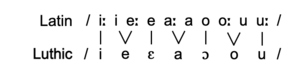

Vowel system

The most sonorous elements of the [[w:Syllable|syllable] are vowels, which occupy the nuclear position. They are prototypical mora-bearing elements, with simple vowels monomoraic, and long vowels bimoraic. Latin vowels occurred with one of five qualities and one of two weights, that is short and long /i e a o u/. At first, weight was realised by means of longer or shorter duration, and any articulatory differences were negligible, with the short:long opposition stable. Subtle articulatory differences eventually grow and lead to the abandonment of length, and reanalysis of vocal contrast is shifted solely to quality rather than both quality and quantity; specifically, the manifestation of weight as length came to include differences in tongue height and tenseness, and quite early on, /ī, ū/ began to differ from /ĭ, ŭ/ articulatorily, as did /ē, ō/ from /ĕ, ŏ/. The long vowels were stable, but the short vowels came to be realised lower and laxer, with the result that /ĭ, ŭ/ opened to [ɪ, ʊ], and /ĕ, ŏ/ opened to [ε, ɔ]. The result is the merger of Latin /ĭ, ŭ/ and /ē, ō/, since their contrast is now realised sufficiently be their distinct vowel quality, which would be easier to articulate and perceive than vowel duration.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː ĩː | u uː ũː | |

| Mid | e eː ẽː | o oː õː | |

| Open | ä äː ä̃ː |

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ɪ iː ĩː | ʊ uː ũː | |

| Mid | ε eː ẽː | ɔ oː õː | |

| Open | ä äː ä̃ː |

Unstressed a resulted in a slightly raised a [ɐ]. In hiatus, unstressed front vowels become /j/, while unstressed back vowels become /w/.

In addition to monophthongs, Luthic has diphthongs, which, however, are both phonemically and phonetically simply combinations of the other vowels. None of the diphthongs are, however, considered to have distinct phonemic status since their constituents do not behave differently from how they occur in isolation, unlike the diphthongs in other languages like English and German. Grammatical tradition distinguishes “falling” from “rising” diphthongs, but since rising diphthongs are composed of one semiconsonantal sound [j] or [w] and one vowel sound, they are not actually diphthongs. The practice of referring to them as “diphthongs” has been criticised by phoneticians like Alareico Villavolfo.

Absorption of nasals before fricatives

This is the source of such alterations as modern Standard Luthic fimfe [ˈfĩ.(p͡)fe] “five”, monþo [ˈmõ.(t͡)θu] “mouth” versus Gothic fimf [ˈɸimɸ] “id.”, munþs [ˈmunθs] “id.” and German fünf [fʏnf] “id.”, Mund [mʊnt] “id.”.

Monophthongization

The diphthongs au, ae and oe [au̯, ae̯, oe̯] were monophthongized (smoothed) to [ɔ, ɛ, e] by Gothic influence, as the Germanic diphthongs /ai/ and /au/ appear as digraphs written ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ in Gothic. Researchers have disagreed over whether they were still pronounced as diphthongs /ai̯/ and /au̯/ in Ulfilas' time (4th century) or had become long open-mid vowels: /ɛː/ and /ɔː/: ains [ains] / [ɛːns] “one” (German eins, Icelandic einn), augō [auɣoː] / [ɔːɣoː] “eye” (German Auge, Icelandic auga). It is most likely that the latter view is correct, as it is indisputable that the digraphs ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ represent the sounds /ɛː/ and /ɔː/ in some circumstances (see below), and ⟨aj⟩ and ⟨aw⟩ were available to unambiguously represent the sounds /ai̯/ and /au̯/. The digraph ⟨aw⟩ is in fact used to represent /au/ in foreign words (such as Pawlus “Paul”), and alternations between ⟨ai⟩/⟨aj⟩ and ⟨au⟩/⟨aw⟩ are scrupulously maintained in paradigms where both variants occur (e.g. taujan “to do” vs. past tense tawida “did”). Evidence from transcriptions of Gothic names into Latin suggests that the sound change had occurred very recently when Gothic spelling was standardised: Gothic names with Germanic au are rendered with au in Latin until the 4th century and o later on (Austrogoti > Ostrogoti).

Palatalisation

Early evidence of palatalized pronunciations of /tj kj/ appears as early as the 2nd–3rd centuries AD in the form of spelling mistakes interchanging ⟨ti⟩ and ⟨ci⟩ before a following vowel, as in ⟨tribunitiae⟩ for tribuniciae. This is assumed to reflect the fronting of Latin /k/ in this environment to [c ~ t͡sʲ]. Palatalisation of the velar consonants /k/ and /ɡ/ occurred in certain environments, mostly involving front vowels; additional palatalisation is also found in dental consonants /t/, /d/, /l/ and /n/, however, these are not palatalised in word initial environment.

- Latin amīcus [äˈmiː.kus̠ ~ äˈmiː.kʊs̠], amīcī [äˈmiː.kiː] > Luthic amico [ɐˈmi.xu], amici [ɐˈmi.t͡ʃi].

- Gothic giba [ˈɡiβa] > Luthic giva [ˈd͡ʒi.vɐ].

- Latin ratiō [ˈrä.t̪i.oː] > Luthic razione [ʁɐˈd͡zjo.ne]

- Latin fīlius [ˈfiː.li.us̠ ~ ˈfiː.lʲi.ʊs̠] > Luthic fiġlo [ˈfiʎ.ʎu].

- Latin līnea [ˈliː.ne.ä ~ ˈlʲiː.ne.ä] , pugnus [ˈpuŋ.nus̠ ~ ˈpʊŋ.nʊs̠], ācrimōnia [äː.kriˈmoː.ni.ä ~ äː.krɪˈmoː.ni.ä] > Luthic liġna [ˈliɲ.ɲɐ], poġno [ˈpoɲ.ɲu], acremoġna [ɐ.kɾeˈmoɲ.ɲɐ].

Labio-velars remain unpalatalised, except in monosyllabic environment:

- Latin quis [kʷis̠ ~ kʷɪs̠] > Luthic ce [t͡ʃe].

- Gothic qiman [ˈkʷiman] > Luthic qemare [kʷeˈma.ɾe ~ kᶣeˈma.ɾe].

Lenition

The Gotho-Romance family suffered very few lenitions, but in most cases the stops /p t k/ are lenited to /b d ɡ/ if not in onset position, before or after a sonorant or in intervocalic position as a geminate. A similar process happens with /b/ that is lenited to /v/ in the same conditions. The non-geminate rhotic present in Latin is simplified to /ɾ ʁ/. The unstressed labio-velar /kʷ/ delabialises before hard vowels, as in:

- Gothic ƕan [ʍan] > *[kʷɐn] > Luthic can [kɐn].

- Latin nunquam [ˈnuŋ.kʷä̃ː ~ ˈnʊŋ.kʷä̃ː] > Luthic nogca [ˈnoŋ.kɐ].

Luthic is further affected by the Gorgia Toscana effect, where every plosive is spirantised (or further approximated if voiced). Plosives, however, are not affected if:

- Geminate.

- Labialised.

- Nearby another fricative.

- Nearby a rhotic, a lateral or nasal.

- Stressed and anlaut.

Fortition

In every case, /j/ and /w/ are fortified to /d͡ʒ/ and /v/, except when triggered by hiatus collapse. The Germanic /ð/ and /xʷ ~ hʷ ~ ʍ/ are also fortified to /d/ and /kʷ/ in every position; which can be further lenited to /d͡z/ and /k ~ t͡ʃ/ in the environments given above. The Germanic /h ~ x/ is fortified to /k/ before a rhotic or a lateral, as in:

- Gothic hlaifs [ˈhlɛːɸs] > Luthic claifo [ˈklɛ.fu].

- Gothic hriggs [ˈhriŋɡs ~ ˈhriŋks] > Luthic creggo [ˈkɾeŋ.ɡu].

Coda consonants with similar articulations often sandhi, triggering a kind of syntactic gemination, it also happens with oxytones:

- Il catto [i‿kˈkat.tu].

- Ed þû, ce taugis? [e‿θˈθu | t͡ʃe ˈtɔ.d͡ʒis?].

- La cittâ stâþ sporca [lɐ t͡ʃitˈta‿sˈsta‿sˈspoɾ.kɐ].

Regarding the absorption of nasals before fricatives, voiceless fricatives are often fortified to affricates after alveolar consonants, such as /n l ɾ/, or general nasals:

- Il monþo [i‿mˈmõ.t͡θu].

- L’inferno [l‿ĩˈp͡fɛɾ.nu].

- La salsa [lɐ ˈsal.t͡sɐ].

- L’arsenale [l‿ɐɾ.t͡seˈna.le].

Deletion

In some rare cases, the consonants are fully deleted (elision), as in the verb havere, akin to Italian avere, which followed a very similar paradigm and evolution:

- 1st person indicative present: Latin habeō, Gothic haba, Luthic hô, Italian ho.

- 2nd person indicative present: Latin habēs, Gothic habais, Luthic haïs, Italian hai.

- 3rd person indicative present: Latin habet, Gothic habaiþ, Luthic hâþ, Italian ha.

Vowels other than /a/ are often syncopated in unstressed word-internal syllables, especially when in contact with liquid consonants:

- Latin angulus [ˈäŋ.ɡu.ɫ̪us̠ ~ ˈäŋ.ɡʊ.ɫ̪ʊs̠] > Luthic agglo [ˈaŋ.ɡlu].

- Latin speculum [ˈs̠pɛ.ku.ɫ̪ũː ~ ˈs̠pɛ.kʊ.ɫ̪ũː] ~ Luthic speclȯ [ˈspɛ.klo].

- Latin avunculus [äˈu̯uŋ.ku.ɫ̪us̠ ~ äˈu̯ʊŋ.kʊ.ɫ̪ʊs̠] > Luthic avogclo [ɐˈvoŋ.klu].

Phonotactics

Luthic allows up to three consonants in syllable-initial position, though there are limitations. The syllable structure of Luthic is (C)(C)(C)(G)V(G)(C)(C). As with English, there exist many words that begin with three consonants. Luthic lacks bimoraic (diphthongs and long vowels), as the so-called diphthongs are composed of one semiconsonantal (glide) sound [j] or [w].

| C₁ | C₂ | C₃ |

|---|---|---|

| f v p b t d k ɡ | ɾ | j w |

| s | p k | ɾ l |

| s | f t | ɾ |

| z | b | l |

| z | d ɡ | ɾ |

| z | m n v d͡ʒ ɾ l | — |

| p b f v k ɡ | ɾ l | — |

| ɡ | n l | — |

| pʰ t tʰ kʰ d | ɾ | — |

| θ | v ɾ | — |

| kʷ ɡʷ t͡s t͡ʃ d͡ʒ ʃ h ð ʁ ɲ l ʎ | — | — |

CC

- /s/ + any voiceless stop or /f/;

- /z/ + any voiced stop, /v d͡ʒ m n l ɾ/;

- /f v/, or any stop + /ɾ/;

- /f v/, or any stop except /t d/ + /l/;

- /f v s z/, or any stop or nasal + /j w/;

- In Graeco-Roman words origin which are only partially assimilated, other combinations such as /pn/ (e.g. pneumatico), /mn/ (e.g. mnemonico), /tm/ (e.g. tmesi), and /ps/ (e.g. pseudo-) occur.

As an onset, the cluster /s/ + voiceless consonant is inherently unstable. Phonetically, word-internal s+C normally syllabifies as [s.C]. A competing analysis accepts that while the syllabification /s.C/ is accurate historically, modern retreat of i-prosthesis before word initial /s/+C (e.g. miþ isforza “with effort” has generally given way to miþ sforzȧ) suggests that the structure is now underdetermined, with occurrence of /s.C/ or /.sC/ variable “according to the context and the idiosyncratic behaviour of the speakers.”

CCC

- /s/ + voiceless stop or /f/ + /ɾ/;

- /z/ + voiced stop + /ɾ/;

- /s/ + /p k/ + /l/;

- /z/ + /b/ + /l/;

- /f v/ or any stop + /ɾ/ + /j w/.

| V₁ | V₂ | V₃ |

|---|---|---|

| a ɐ e ɛ | i [j] u [w] | — |

| o ɔ | i [j] | — |

| i [j] | e o | — |

| i [j] | ɐ ɛ ɔ | i [j] |

| i [j] | u [w] | o |

| u [w] | ɐ ɛ ɔ | i [j] |

| u [w] | e o | — |

| u [w] | i | — |

The nucleus is the only mandatory part of a syllable and must be a vowel or a diphthong. In a falling diphthong the most common second elements are /i̯/ or /u̯/. Combinations of /j w/ with vowels are often labelled diphthongs, allowing for combinations of /j w/ with falling diphthongs to be called triphthongs. One view holds that it is more accurate to label /j w/ as consonants and /jV wV/ as consonant-vowel sequences rather than rising diphthongs. In that interpretation, Luthic has only falling diphthongs (phonemically at least, cf. Synaeresis) and no triphthongs.

| C₁ | C₂ |

|---|---|

| m n l ɾ | Cₓ |

| Cₓ | — |

Luthic permits a small number of coda consonants. Outside of loanwords, the permitted consonants are:

- The first element of any geminate.

- A nasal consonant that is either /n/ (word-finally) or one that is homorganic to a following consonant.

- /ɾ/ and /l/.

- /s/ (though not before fricatives).

Prosody

Luthic is quasi-paroxytonic, meaning that most words receive stress on their penultimate (second-to-last) syllable. Monosyllabic words tend to lack stress in their only syllable, unless emphasised or accentuated. Enclitic and other unstressed personal pronouns do not affect stress patterns. Some monosyllabic words may have natural stress (even if not emphasised), but it is weaker than those in polysyllabic words.

- rasda (ʀᴀ-sda ~ ʀᴀs-da) /ˈʁa.zdɐ ~ ˈʁaz.dɐ/;

- Italia (i-ᴛᴀ-lia) /iˈta.ljɐ];

- approssimativamente (ap-pros-si-ma-ti-va-ᴍᴇɴ-te) /ɐp.pɾos.si.mɐ.θi.vɐˈmen.te/.

Compound words have secondary stress on their penultimate syllable. Some suffixes also maintain the suffixed word secondary stress.

- panzar + campo + vaġno > panzarcampovaġno (ᴘᴀɴ-zar-ᴄᴀᴍ-po-ᴠᴀ-ġno) /ˌpan.t͡sɐɾˌkam.poˈvaɲ.ɲu/;

- broþar + -scape > broþarscape (ʙʀᴏ-þar-sᴄᴀ-pe) /ˌbɾo.θɐɾˈska.fe/.

Secondary stress is however often omitted by Italian influence. Tetrasyllabic (and beyond) words may have a very weak secondary stress in the fourth-to-last syllable (i.e. two syllables before the main or primary stress).

Research

Luthic is a well-studied language, and multiple universities in Italy have departments devoted to Luthic or linguistics with active research projects on the language, mainly in Ravenna, such as the Linguistic Circle of Ravenna (Luthic: Creizzo Rasdavitascapetico Ravennai; Italian: Circolo Linguistico di Ravenna) at Ravenna University, and there are many dictionaries and technological resources on the language. The language council Gafaurdo faul·la Rasda Lûthica also publishes research on the language both nationally and internationally. Academic descriptions of the language are published both in Luthic, Italian and English. The most complete grammar is the Grammatica ġli Lûthicai Rasdai (Grammar of the Luthic Language) by Alessandro Fiscar & Luca Vaġnar, and it is written in Luthic and contains over 800 pages.

Multiple corpora of Luthic language data are available. The Luthic Online Dictionary project provides a curated corpus of 35,000 words.

History

The Ravenna School of Linguistics evolved around Giovanni Laggobardi and his developing theory of language in linguistic structuralism. Together with Soġnafreþo Rossi he founded the Circle of Linguistics of Ravenna in 1964, a group of linguists based on the model of the Prague Linguistic Circle. From 1970, Ravenna University offered courses in languages and philosophy but the students were unable to finish their studies without going to Accademia della Crusca for their final examinations.

Ravenna University Circle of Phonological Development (Luthic: Creizzo Sviluppi Phonologici giȧ Accademiȧ Ravennȧ) was developed in 1990, however very little research has been done on the earliest stages of phonological development in Luthic.

Ravenna University Circle of Theology (Luthic: Creizzo Theologiai giȧ Accademiȧ Ravennȧ) was developed in 2000 in association with the Ravenna Cathedral or Metropolitan Cathedral of the Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ (Luthic: Cathedrale metropolitana deï Osstassi Unsari Signori Gesosi Christi; Italian: Cattedrale metropolitana della Risurrezione di Nostro Signore Gesù Cristo; Duomo di Ravenna).

Aina lettura essenziale summȧ importanzȧ, inu andarogiugga.

“An essential lecture, of the highest importance, without equivalents.”

The Handbook of Luthic Linguistics, Culture and Religion

In 2012, a collaboration of the Circle of Linguistics, the Circle of Phonological Development and the Circle of Theology resulted in The Handbook of Luthic Linguistics, Culture and Religion (Luthic: Il Handobuoco Rasdavitascapeticai, Colturai e Religioni Luthicai) initiated in 2005 by Lucia Giamane, designed to illuminate an area of knowledge that encompasses both general linguistics and specialised, philologically oriented linguistics as well as those fields of science that have developed in recent decades from the increasingly extensive research into the diverse phenomena of communicative action.

Grammar

Luthic grammar is almost typical of the grammar of Romance languages in general. Cases exist for personal pronouns (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), and unlike other Romance languages (except Romanian), they also exist for nouns, but are often ignored in common speech, mainly because of the Italian influence, a language who lacks noun cases. There are three basic classes of nouns in Luthic, referred to as genders, masculine, feminine and neuter. Masculine nouns typically end in -o, with plural marked by -i, feminine nouns typically end in -a, with plural marked by -ai, and neuter nouns typically end in -ȯ, with plural marked by -a. A fourth category of nouns is unmarked for gender, ending in -e in the singular and -i in the plural; a variant of the unmarked declension is found ending in -r in the singular and -i in the plural, it lacks neuter nouns:

Examples:

| Definition | Gender | Singular nominative | Plural nominative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Son | Masculine | Fiġlo | Fiġli |

| Flower | Feminine | Bloma | Blomai |

| Fruit | Neuter | Acranȯ | Acrana |

| Love | Masculine | Amore | Amori |

| Art | Feminine | Crafte | Crafti |

| Water | Neuter | Vadne | Vadni |

| King | Masculine | Regġe | Regġi |

| Heart | Neuter | Hairtene | Hairteni |

| Father | Masculine | Fadar | Fadari |

| Mother | Feminine | Modar | Modari |

Declension paradigm in formal Standard Luthic:

| Number | Case | o-stem m | a-stem f | o-stem n | i-stem unm | r-stem unm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | nom. | dago | geva | hauviþȯ | crafte | broþar |

| acc. | dagȯ | geva | hauviþȯ | crafte | broþare | |

| dat. | dagȧ | gevȧ | hauviþȧ | crafti | broþari | |

| gen. | dagi | gevai | hauviþi | crafti | broþari | |

| Plural | nom. | dagi | gevai | hauviþa | crafti | broþari |

| acc. | dagos | gevas | hauviþa | craftes | broþares | |

| dat. | dagom | gevam | hauviþom | craftivo | broþarivo | |

| gen. | dagoro | gevaro | hauviþoro | craftem | broþarem |

Pronouns

Luthic, like Latin and Gothic, inherited the full set of Indo-European pronouns: personal pronouns (including reflexive pronouns for each of the three grammatical persons), possessive pronouns, both simple and compound demonstratives, relative pronouns, interrogatives and indefinite pronouns. Each follows a particular pattern of inflection (partially mirroring the noun declension), much like other Indo-European languages. Although Luthic inherited a paradigm extremely close to Gothic (and Common Germanic), the Italic influence is visible in the genitive and plural formations.

| PIE | Latin | Gothic | German | Luthic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *u̯ei̯ nom, *n̥s acc | nōs nom/acc | weis nom, uns acc | wir nom, uns acc | vi nom, unse acc |

| Number | Case | 1st person | 2st person | 3rd person | reflexive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | |||||

| Singular | nom. | ic | þû | is | ia | ata | — |

| acc. | mic | þuc | inȯ | ina | ata | sic | |

| dat. | mis | þus | iȧ | iȧ | iȧ | sis | |

| dat. | meina | þeina | eis | isai | eis | seina | |

| Singular | nom. | vi | gi | eis | isai | ia | — |

| acc. | unse | isve | eis | isas | ia | sic | |

| dat. | unsis | isvis | eis | eis | eis | sis | |

| gen. | unsara | isvara | eisôro | eisâro | eisôro | seina | |

| Number | Case | 1st person singular | 2st person singular | 3rd person singular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | meino | meina | meinȯ | þeino | þeina | þeinȯ | seino | seina | seinȯ |

| acc. | meinȯ | meina | meinȯ | þeinȯ | þeina | þeinȯ | seinȯ | seina | seinȯ | |

| dat. | meinȧ | meinȧ | meinȧ | þeinȧ | þeinȧ | þeinȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | |

| gen. | meini | meinai | meini | þeini | þeinai | þeini | seini | seinai | seini | |

| Plural | nom. | meini | meinai | meina | þeini | þeinai | þeina | seini | seinai | seina |

| acc. | meinos | meinas | meina | þeinos | þeinas | þeina | seinos | seinas | seina | |

| dat. | meinom | meinam | meinom | þeinom | þeinam | þeinom | seinom | seinam | seinom | |

| gen. | meinoro | meinaro | meinoro | þeinoro | þeinaro | þeinoro | seinoro | seinaro | seinoro | |

| Number | Case | 1st person singular | 2st person singular | 3rd person singular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | unsar | unsara | unsarȯ | isvar | isvara | isvarȯ | seino | seina | seinȯ |

| acc. | unsare | unsara | unsarȯ | isvare | isvara | isvarȯ | seinȯ | seina | seinȯ | |

| dat. | unsari | unsarȧ | unsarȧ | isvari | isvarȧ | isvarȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | |

| gen. | unsari | unsarai | unsari | isvari | isvarai | isvari | seini | seinai | seini | |

| Plural | nom. | unsari | unsarai | unsara | isvari | isvarai | isvara | seini | seinai | seina |

| acc. | unsares | unsaras | unsara | isvares | isvaras | isvara | seinos | seinas | seina | |

| dat. | unsarivo | unsaram | unsarom | isvarivo | isvaram | isvarom | seinom | seinam | seinom | |

| gen. | unsarem | unsararo | unsaroro | isvarem | isvararo | isvaroro | seinoro | seinaro | seinoro | |

The pronouns unsar, isvar have an irregular declension, being declined like an unmarked adjective in the masculine gender and marked in the other genders. Every possessive pronoun is declined like an o-stem adjective for masculine and neuter gender, while its feminine counterpart is declined as an a-stem adjective

Interrogative and indefinite pronouns are indeclinable by case and number: