Verse:Irta/Music: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

(→Arabo-Japanese: izae should be -i-) Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

idea: "what if maqams were pentatonic" | idea: "what if maqams were pentatonic" | ||

Arabo-Japanese music consists of various modes and melodic tropes called ''makān'' and ''āwāji''. Arabo-Japanese ''makān''s are mostly pentatonic where certain notes are played with vibrato by default. For instance ''makān- | Arabo-Japanese music consists of various modes and melodic tropes called ''makān'' and ''āwāji''. Arabo-Japanese ''makān''s are mostly pentatonic where certain notes are played with vibrato by default. For instance ''makān-i-Hirajōshi'' consists of the scale C D Eb G Ab with vibratos on the notes Eb and Ab. In addition there are non-octave ''makān''s like the "pentatonic" scale C D Eb G Ab Bb with vibratos on Eb and Bb. | ||

Arabo-Japanese "ajnas" are either trichords spanning a perfect fourth or tetrachords spanning a perfect fifth. An exception is ??? which spans a diminished fifth: C E F Gb. | Arabo-Japanese "ajnas" are either trichords spanning a perfect fourth or tetrachords spanning a perfect fifth. An exception is ??? which spans a diminished fifth: C E F Gb. | ||

Revision as of 12:01, 17 June 2022

Azalic music

Azalic music is built up on similar principles to ancient Greek music theory, but they divide string lengths into constructible ratios which aren't always rational. The most common tunings used in Azalic music divide a JI interval, most commonly 2/1, 3/2 or 12/7, into 16 equal parts, and various MOS subsets of these are used for melody, particularly Lemba, Mavila, and Magic temperaments.

Common Mavila scales used in Azalic music are the Antilocrian mode, 3 2 2 3 2 2 2, and the seventh mode of the harmonic minor, 3 2 3 2 2 3 1.

In Irtan cultures outside the Azalic Urheimat but influenced by Azalic culture, 16ed12/7, and its octave equivalent counterpart 41edo, became the most prominent tuning whereas Irta's North Africa (the Azalic Urheimat) mostly uses variations on 16 tone octave equivalent and related scales. Knench music, which is generally polyphonic, uses harmonic series approximations to 16edo.

Azalic scales directly influenced the music of Irta's Southern United States and Mexico.

Irta Irish classical music

"If Irish/Scottish folk music is the same as in our timeline what would Irish elite music be like"

Irta Irish Renaissance music

Should be a development of sung bardic poetry, with French Renaissance influences

Irish Counter-Remonition

Tuning: Fixed pitch instruments are tuned to 5 to 10 note subsets of 2-3 chains of Pyth fifths separated by 5/4, commas are intentionally used. At some point this is standardized to 34edo

Names for the tuning standard and notes relative to it (like how Arabs don't use all 24 notes of 24edo)

Irta Irish Romanticism

post-2nd Rem; exists alongside "Western classical" music and influences modernist strains of it

Albionian and folk Irish music influences, Irish lieder are a tradition along with French and Azalic English ones (reaction to excesses of the Counter-Remonition period)

Irish Romantic music in Irta generally uses small scales, mostly 5 limit though some 7's and 11's show up

In literature, nature poetry makes a comeback

Irta Spanish music

Irta's Spain uses Azalic instruments and forms.

The 18th century guitarist Redwen Arantzazumab was responsible for creating many modern Irta Spanish musical styles. Some of these such as Azalic flamenco have influenced music in other parts of Irta. Arantzazumab's treatise The Musical Spirit is widely read and is perhaps one of the most misunderstood musical treatises in Irta.

Western European music

Three distinct classical styles emerge in Western Europe in Irta, all of which are popular. The first two arise directly out of Remonitionism -- the style that arises from the First Remonition is a neo-medievalism derived from the music of various Italic-speaking cultures as well as Tsarfati Jewish music, but Second Remonitionist music is much more meditative and chanting/intoned singing-based.

Irta Baroque

A neo-medievalist movement which develops in France, Spain and Italy, "what if Baroque used 17edo/17wt"

Baroque dance suites in 17edo which use Baroque dance rhythms but not our Baroque harmony; canons and fugues, but not using Fuxian counterpoint

2-part counterpart likes resolving to fifths and uses tons of Machaut cadences (Eb-G -> D-A, Ed-Gt -> D-A, E-G# -> D-A)

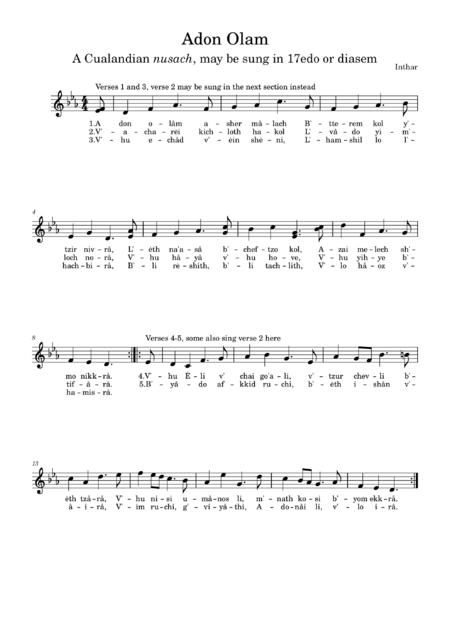

Nowadays First Remonitionist styles are much more popular in Riphea, Remonitionist colonies in Polynesia, and Cualand.

John Wellwise /wɛlɪz/ is the counterpoint guy (interpreting "Fuxian" as Mandarin 富賢)

Irta Baroque trends

Bleu temperament often shows up as an attempt to capture an "Azalic" sound in a 17edo framework

Second Remonitionist music

Early Second Remonitionist musical styles are derived from Greek Buddhist chanting and Azalic polyphonic traditions found in Irta, and follows a system of four roughly equal divisions of a perfect fifth. (Incidentally this is very similar to our timeline's Georgian music)

Both practices were dominant among Remonitionists who first migrated to Tricin, and the most common musical system among Remonitionists in Cualand is 41edo.

Classical and Romantic music

Classical and Romantic music are very similar to our timeline.

Triadic polyphony in Irta evolved mainly from folk adaptations of Second Remonitionist polyphony, with melodic tendencies as in our timeline's "expressive intonation" resulting in a roughly 12 tone division of the octave. A notable difference is that the piano isn't as prominent -- in contrast, string ensembles and voice are given precedence which makes the classical idea of intonation in Irta much more fluid than in our timeline, with theorists often acknowledging subtle variations of a note, and there are various proposals to explain intonation in Irtan classical music. Intonational variation correlates with:

- the placement of notes within a phrase, as well as scalar and harmonic context,

- mood, and

- region (e.g. western parts of Hyperfrance use wider leading tones and narrower fifths compared to Riphea). This makes it especially hard for Irtan classical composers to codify an intonational system.

Many composers in Irta regard fixed pitch instruments as inadequate for capturing the nuances of intonation, and these composers mostly write for strings, voice, and trombone. Some developed cross-fingering techniques for woodwinds to better approximate expressive intonation.

Interestingly this results in Irtan Western classical music being thought of as one of the prominent microtonal world traditions and there are various myths across Irta about the number of notes in Western music, 21 and 35 being commonly cited numbers because of the notation system.

Artistic movements and composers

The most popular 19th century Western composer in Irta is Mahi Driu, who was also a cello virtuoso. She wrote over 50 string quartets, 6 cello suites and several concerti for cello and string ensemble.

Other prominent figures:

- Utvan Okyv, operatic composer

- Arexudh Šarie, violinist and composer of caprices

- Žufasva Dertai, cellist

- Ženviv Fidutvan

- Irta's Chopin -- of Riphean origin (birth name Zenevīve Antōnastukte); famous for writing adaptations of Riphean folk dances as well as Riphean-inspired violin music

- Krod Erfebh, composer of symphonies

- Máirtín Mac Seanlaoich, composer of Irish-language art songs

- In Irta, "The Raven" most commonly refers to this person's art song "An Fiach Dubh", but it's not on the same poem as our Edgar Allan Poe's

- Éamon Budigēgı, composer who incorporated elements of classical Arabic music into Irta Irish Romanticism

- Saoirse Ní Mhaolagáin, symphonist, part of the "Second Viennese School"

- her 9th symphony introduces the pandiatonic style for the first time in Irta

- Tricky violin concertos using modal figurations that stump violinists?

- Wildworth Kim, ethnomusicologist, microtonalist and author of a treatise proposing extended Pythagorean intonation

- Introduces a Bosanquet-like layout which becomes controversial?

The Second Viennese school isn't a thing in Irta; the equivalent is a resurgence of modes outside the major/minor system, developed in Irta's Ireland as a classical take on Irtan Irish Romanticism. Pandiatonicism as well as a total abandonment of earlier classical musical gestures is a part of this trend. This is part of a broader artistic movement that features modernist poetry and abstract painting. This abstractness becomes the most prominent style in modern music in Irta's British Isles and Quelfton and gives rise to various forms of experimentation such as a "tonal New Complexity" style pioneered by Quelftonian composer ____. Irtan "Second Viennese" composers use 53edo as a rough codification of the notes found in earlier classical melodic tropes.

Riphean

Folk traditions of Riphea are revived as a part of the Nōje Niđjaste movement and a distinctive Riphean style of classical music develops from this. The "Riphean style" was subsequently incorporated into concert music by late 19th century Irtan composers.

Arabo-Japanese

idea: "what if maqams were pentatonic"

Arabo-Japanese music consists of various modes and melodic tropes called makān and āwāji. Arabo-Japanese makāns are mostly pentatonic where certain notes are played with vibrato by default. For instance makān-i-Hirajōshi consists of the scale C D Eb G Ab with vibratos on the notes Eb and Ab. In addition there are non-octave makāns like the "pentatonic" scale C D Eb G Ab Bb with vibratos on Eb and Bb.

Arabo-Japanese "ajnas" are either trichords spanning a perfect fourth or tetrachords spanning a perfect fifth. An exception is ??? which spans a diminished fifth: C E F Gb.

Arabic

No maqam 3ajam in places that use a 17edo-based theory; Irta's maqam 3ajam comes from 5-limit major in Irta Irish theory, often approximated with 34edo

Corsican

Sean-nós style in Arabic maqams, this style is called ānə (cognate to Maltese għana) in Corsican Arabic

New maqams

Some maqams named after Irish or Celtic places or scales in Irta Irish classical music

More maqams with Arabic names like "Rahat Al Arwah"

Irta Irish borrows maqām names (via Corsican Arabic, e.g. Rāhatı alı-Arvēh) and the term megāmı itself, and translates other maqam terms

Tsarfati

Tsarfati music is stylistically halfway between our Ashkenazi music (due to Irta Eastern European music being similar to our timeline's) and Irish folk music, and influenced First Remonitionist music.

Before the Tsarfati Enlightenment, rhythmic elements from Irish prosody, such as Scotch snaps, used to be considered a regionalism, because most dialects of Ăn Yidiș do not have vowel length. However, during the Tsarfati Enlightenment period, Irta Irish elements including Irish prosody became a trend. This was less strong in areas where Hasidism was popular.

Older Tsarfati styles, particularly cantillation tropes, are the source of Gregorian chant melodies in Irta.

Tuning

Intonation often happens by ear and is not necessarily JI-based (cf. maqam music). Tuning systems used differ by the individual community. Fixed pitch instruments use various overtone scales and detempered 34edo. Neutral intervals are commonly used as in maqam.

Liturgy uses diatonic or maqam modes:

- Torah readings use Mixolydian or Jiharkah

- Haftarot use Aeolian or Nairuz

- Non-Eicha Megillot use Dorian or Rast

- Esther uses this melody (except parts where the Eicha melody is used): https://www.virtualcantor.com/Esther1.mp3

- Eicha uses Phrygian or Bayati

- Most blessings use the same scales as our Ashkenazim do

- Some blessings and prayers use a tuning of Lydian with a supermajor 3rd

Todo: Cantillation tropes

Folk music

Tsarfati Jewish folk songs are known as טאָנתּאן dontăn in Ăn Yidiș (singular טאָן don; cognate to Irish dán 'poem (among other meanings)'). They may be in Ăn Yidiș or in a macaronic mixture of Ăn Yidiș, Hebrew, and other languages. They have some traditional Hivantish, our timeline's Eastern European, and our timeline's Irish elements but are unique. Like in our timeline, Hasidic Judaism is also an influence with its emphasis on dancing, devotion, and wordless melodies.

Instruments from Gaelic music:

- pib-ilăn - uilleann pipes

- fehăł (from in-universe OIr **fethal, from Early Romance *vitola) - fiddle

- cłorșăch - a version of the Welsh triple harp adapted to common Tsarfati scales (If you say "Jew's harp" in Irta they'd likely think you mean this.)

Instruments from Hivantish music:

- șeyņăł - kantele

Other instruments, often used in larger ensembles:

- harpsichord -- a staple of Irta klezmer

- organ

- tromba marina and horns for harmonic series scales

Modern cłorșăchăn are usually electro-acoustic.

Talma

Hebrew cantillation

Based on oneirotonic, uses modes such as LLLSLSLS, LLSLLSLS, LLSLLSLS, LSLLSLLS, LSLSLSAS, LSLSLLLS, SLSLLSLL, with varying tunings which can change when singing; marimbas are common in synagogues

Cualand

Hebrew cantillation

Cantillation tropes in Cualand are diatonic, LCJI-based, or overtone scale-based. Some melodies use Locrian. Doctrinally Judaism is no more weird than the full range of Rabbinic Judaism in our timeline.

Primodality

Evolution

Primodality is invented in Cualand. Like in our timeline, primodality is chord-scale theory applied to overtone scales. In Irta, chord-scale theory arises within the Irta Arab maqam tradition (which has a standardized abstract gamut) whereas the original maqam culture survives in other cultures such as Turkic and Corsican music.