Grekelin: Difference between revisions

m (→Evolution) |

m (Some extra information and fixes) |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

{{Infobox language | {{Infobox language | ||

|name = Grekelin | |name = Grekelin | ||

|nativename = | |nativename = To gnudzsa Grekelenikin, Rumejkin | ||

|state = [[w:Slovakia|Slovakia]], [[w:Hungary|Hungary]], [[w:Serbia|Serbia]] | |state = [[w:Slovakia|Slovakia]], [[w:Hungary|Hungary]], [[w:Serbia|Serbia]] | ||

|created = 2023 | |created = 2023 | ||

|image = Grekelin National Flag.png | |||

|imagesize = 200px | |||

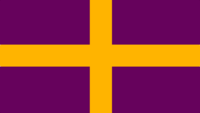

|imagecaption = The Grekelin flag. Largely inspired by the Byzantine design of the time, it signifies the Roman descendance of the Grekelin people. It was adopted formally in 1992 although variations of it were used sparsely in some separatist movements. | |||

|familycolor = Indo-European | |familycolor = Indo-European | ||

|fam2 = [[w:Hellenic languages|Hellenic]] | |fam2 = [[w:Hellenic languages|Hellenic]] | ||

| Line 32: | Line 35: | ||

}} | }} | ||

'''Grekelin''' ([[w:Autoglossonym|Autoglossonym]]: ''Grekelenikin'', pronounced: ''[grɛ.kɛ.ˈɫɛ.ni.kin]''), also known as '''Rhumaecen'''<ref name=Rhumaecen/> (Grekelin: ''Rumejkin'', [ɾuˈmɛi̯ˌkin], lit. "The Roman one") is a [[w: | '''Grekelin''' ([[w:Autoglossonym|Autoglossonym]]: ''Grekelenikin'', pronounced: ''[grɛ.kɛ.ˈɫɛ.ni.kin]''), also known as '''Rhumaecen'''<ref name=Rhumaecen/> (Grekelin: ''Rumejkin'', [ɾuˈmɛi̯ˌkin], lit. "The Roman one") is a language derived from [[w:Medieval Greek|Medieval Greek]] spoken in [[w:Vojvodina|Vojvodina]], [[w:Hungary|Southern Hungary]] and some isolated villages of [[w:Slovakia|Slovakia]]. Grekelin split from mainland/Anatolian [[w:Greek language|Greek]] in the late 11th century with the mass settlement of Hungary by [[w:Greeks|Greek]] refugees following the Seljuk Turks' raids. For the largest part of its existence, Grekelin was mostly a spoken language, and the language began systematically being written down around the 19th century (From where it gained it's modern orthography by Catholic priests and scholars). Due to its low social prestige, most of its educated speakers preferred writing in Latin or Hungarian (Also Koine before the Catholicisation of the Grekelin-speaking people) and few texts were written until then in Grekelin, most of which used the Greek script instead (See [[Old Grekelin]]). | ||

As a related language to Greek, Grekelin shares with Modern Greek and its dialects multiple features and cognates. The language, although officially having a free word order, has become an SOV one (As opposed to most Indo-European languages which are SVO) due to extensive Hungarian influence. It's core vocabulary has remained Greek however many Hungarian words can be found often in the language (Especially those relating to law and government), due to the strong adstratum formed by Hungarian (Though, due to geography, the Slavic dialect got its name from its stronger Slavic influence). Grekelin is the most isolated Hellenic language currently in the entire world, with about 1200 kilometers separating it from the closest Greek speaking territory. | As a related language to Greek, Grekelin shares with Modern Greek and its dialects multiple features and cognates. The language, although officially having a free word order, has become an SOV one (As opposed to most Indo-European languages which are SVO) due to extensive Hungarian influence. It's core vocabulary has remained Greek however many Hungarian words can be found often in the language (Especially those relating to law and government), due to the strong adstratum formed by Hungarian (Though, due to geography, the Slavic dialect got its name from its stronger Slavic influence). Grekelin is the most isolated Hellenic language currently in the entire world, with about 1200 kilometers separating it from the closest Greek speaking territory. | ||

| Line 52: | Line 55: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Nasal | ! Nasal | ||

| /m/ || /n/ || || || /ɲ/ || | | /m/ || /n/ || || || /ɲ/ || /ŋ/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Stop | ! Stop | ||

| Line 93: | Line 96: | ||

<small>'' * Although it only appears in Hungarian or German loanwords, it is often written down using "ö", so people that write the language consider it a native sound. It is considered more of a marginal phoneme.'' </small> | <small>'' * Although it only appears in Hungarian or German loanwords, it is often written down using "ö", so people that write the language consider it a native sound. It is considered more of a marginal phoneme.'' </small> | ||

Although Grekelin does have diphthongs, they appear rarely and usually merge into one vowel when realized. Most of these diphthongs are '''not''' inherited from Greek directly, but developed on their own over the centuries. | Although Grekelin does have diphthongs, they appear rarely and usually merge into one vowel when realized. Most of these diphthongs are '''not''' inherited from Greek directly, but developed on their own over the centuries. | ||

| Line 114: | Line 115: | ||

|} | |} | ||

Grekelin does not favor consonant clusters, often using metathesis to break them apart. The only exception are affricates since they are considered a single sound in Grekelin. | Grekelin does not favor consonant clusters, often inserting vowels or using metathesis to break them apart. The only exception are affricates since they are considered a single sound in Grekelin. | ||

Although not written, the final consonant (If the word ends with a consonant) always becomes devoiced in colluquial speech. | Although not written, the final consonant (If the word ends with a consonant) always becomes devoiced in colluquial speech. | ||

| Line 135: | Line 136: | ||

! colspan="4" | Digraphs in Grekelin orthography | ! colspan="4" | Digraphs in Grekelin orthography | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | ei (/ji/) || cs - /t͡ɕ/~/t͡ʃ/ || zs - /ʑ/ || sz - /ɕ/) | ||

|} | |} | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

==Grammar== | ==Grammar== | ||

| Line 159: | Line 158: | ||

===Cases=== | ===Cases=== | ||

Grekelin has 4 cases: Nominative, genitive, accusative and vocative. In the Slavic dialect, another case exists, the dative case. | Grekelin has 4 cases: Nominative, genitive, accusative and vocative. In the Slavic dialect, another case exists, the dative case. Grekelin has developed vowel harmony in the language so while the endings here are influenced by the nearby vowels, other words may have different inflections. While genders in Grekelin are considered extinct, remnants of it exist in the noun endings (a or i/e), so Grekelin is considered to have a separate noun class system that merged with the Indo-European one. | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| Line 169: | Line 168: | ||

| Nominative || To gnudzsa || Ta gnudzsuk | | Nominative || To gnudzsa || Ta gnudzsuk | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Genitive || | | Genitive || C' gnudzsus || Ta gnudzsun | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Accusative || Ecs | | Accusative || Ecs gnudzsan || Ecs gnudzsun | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Vocative || O | | Vocative || O gnudzse || Oh gnudzsen | ||

|} | |} | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| Line 185: | Line 184: | ||

! Case !! Singular !! Plural | ! Case !! Singular !! Plural | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Nominative || E kukli || Ek | | Nominative || E kukli || Ek kukljuk | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Genitive || | | Genitive || c' Kuklu || Co kuklun | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Accusative || Ecs | | Accusative || Ecs kuklin || Ecs kukljuk | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Vocative || | | Vocative || O kukli || Oh kukljuk | ||

|} | |} | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

===Verbs=== | ===Verbs=== | ||

Verbs in Grekelin | Verbs in Grekelin are split into three classes: Weak, strong and irregular. Their classification depends on the last vowel of the word's root (The word without any prefixes and suffixes conveying grammatical information) while the irregulars are outliers in both with their own inflections. The vowels defining strong verbs are /e i y/ and the vowels defining weak verbs are /a o u ø/. The verb class defines the way a word will be inflected for number, tense and mood. Below are two tables showing the present tense inflection for a weak and a strong verb: | ||

===Strong Verbs=== | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ Verb | |+ Strong Verb - "Vlemmo" (To see/To watch) | ||

! Pronoun !! Verb Declension | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Go || Vlemm-o | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Szÿ || Vlemm-s | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Davta || Vlemm | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Mis || Vlemm-men | ||

|- | |||

| Szÿk || Vlemm-te | |||

|- | |||

| Davtak || Vlemm-ne | |||

|} | |} | ||

===Weak Verbs=== | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ Verb | |+ Weak Verb - "Jeboro" (To be able to) | ||

! Pronoun !! Verb Declension | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Go || Jebor-o | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Szÿ || Jebor-as | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Davta || Jebor-a | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Mis || Jebor-amen | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Szÿk || Jebor-ate | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Davtak || Jebor-anda | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Geographic Distribution and Demographics== | ==Geographic Distribution and Demographics== | ||

| Line 309: | Line 306: | ||

| Who? || ''Pkios?'' || /pki̯os/ | | Who? || ''Pkios?'' || /pki̯os/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| What? || '' | | What? || ''Ti?'' || /ti/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| When? || '' | | When? || ''Ponte?'' || /ˈpo.ndɛ/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Where? || ''Pe?'' || /pɛ/ | | Where? || ''Pe?'' || /pɛ/ | ||

| Line 319: | Line 316: | ||

| Why || ''Dzatti?'' || /'d͡zɑti/ | | Why || ''Dzatti?'' || /'d͡zɑti/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Again || '' | | Again || ''Ura'' || /uˈrɑ/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| What is your name? || ''Ti entá a nóma sei?'' || /ti ɛnˈta ɑ ˈno.mɑ sʲi/ | | What is your name? || ''Ti entá a nóma sei?'' || /ti ɛnˈta ɑ ˈno.mɑ sʲi/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| My name is... || ''A | | My name is... || ''A noma mei enta ...''' || /ɑ ˈno.ma mʲi enˈtα/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Do you speak English? || ''Relalíte eís | | Do you speak English? || ''Relalíte eís to Egglézikin?'' || /rɛ.ɫɑˈɫite jis to ɛkˈɫɛ.zikiŋ/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| I do not understand Grekelin. || ''Y nyó a gnúdzsa Grekelénikin.'' || /y ɲo ɑ ˈɡnud͡ʑɑ ɡrɛˈkɛ.ɫɛnikin/ | | I do not understand Grekelin. || ''Y nyó a gnúdzsa Grekelénikin.'' || /y ɲo ɑ ˈɡnud͡ʑɑ ɡrɛˈkɛ.ɫɛnikin/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Help me! || '' | | Help me! || ''Voettja!'' || /ˈvoˈtʲɑ/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| How much is it? || ''Pószo entá?'' || /ˈpoɕo ɛnˈtɑ/ | | How much is it? || ''Pószo entá?'' || /ˈpoɕo ɛnˈtɑ/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| The study of Grekelin sharpens the mind. || '' | | The study of Grekelin sharpens the mind. || ''Mattisi c'Grekelenikis fjann' to essa kovtoérta.'' || /'matkisi t͡si grɛkɛˈɫɛ.nikis pjɑ α ˈɛ.sa kovtoˈɛr.ta/ | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Where are you from? || ''Pe | | Where are you from? || ''Pe este ecs szÿ?'' || /pɛ ˈɛste ɛt͡ɕ ɕy/ | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Dialects== | ==Dialects== | ||

Grekelin | While [[Old Grekelin]] was evolving into the modern Grekelin language, regional, social and stratum factors were influencing Grekelin in many degrees. Old Grekelin had 4 dialects: The Western-Vienna, the Danubian, the Southern and the Savvian dialect. No descendants exist of the first and the last dialects, although the former provided some loanwords to Grekelin and made it to the 19th century. For the sake of history all three dialects will be mentioned in this section. | ||

===Danubian=== | |||

The Danubian dialect is the one spoken in southern Hungary and the base of the standard literary language. It shares most of the Grekelin speakers and it's the one used in education and formal speech. It developed out of homonymous Old Grekelin dialect, having split from the Southern (Slavic) dialect around the 13th century. | |||

===Slavic Dialects=== | |||

The Slavic dialects are split into two subgroups: Northern and Southern. The two are not shared by genetic relationship as the Northern branch split from a blend of Danubian and Slavic speakers during the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent immigration. The northern branch is going extinct today, and can be characterized by a heavy Czech/Slovak influence. The Southern branch on the other hand is thriving south of the Danubian dialect, being an official language of Vojvodina. | |||

====Northern Branch==== | |||

The northern branch has evolved /o/ to /ɔ/ and /y/ to /ɨ/. It also uses an alveolar trill as the main rhotic instead of the southern branch's tap. It also merged weak and strong verb classes into one, similar to Western Grekelin. | |||

=== | ====Southern Branch==== | ||

The | The southern branch is close to the Danubian dialect, largely because the two have constantly been at contact. The most prominent feature is the iotation of word-initial vowels (Danubian dialects also contain this feature, but only for the /e u/ vowels) and the lack of aspiration for consonants before /y/. | ||

The | ===Western Dialect=== | ||

The Western dialect went extinct in the 19th century. It was an evolution of [[Old Grekelin]]'s Western dialect, itself having split from Danubian Grekelin around the 16th century. When the two dialects reentered linguistic contact after the siege of Vienna, many German loanwords entered through it the Danubian dialect. It went extinct eventually as its speakers either switched to German/Hungarian or adopted the Danubian dialect instead. | |||

The most interesting sound change to occur in Western Grekelin was the reduction of plain /a/ to /æ/ and later /ə/ when unstressed. Some subdialects further reduced /o/ to /ɒ/ and then /ɐ/ although that change was only limited to a small area. Apart from those, very little divergence existed from the Danubian Grekelin; Most speakers didn't realize they spoke different dialects without extensive exposure to each other's speech. This is mostly attributed to Western Grekelin becoming a very isolated dialect with little outside influence, mostly limited to trade. | |||

==Example texts== | ==Example texts== | ||

| Line 376: | Line 372: | ||

===Lord's prayer=== | ===Lord's prayer=== | ||

In liturgical usage, Grekelin is rarely a preferred language. The prayers are usually in Hungarian or Serbian, however villages with proportionally larger Grekelin population use a slightly modified form of the lord's prayer, written below. In previous centuries, Latin was also fairly common, and, before the conversion of Grekelin people to Catholicism, Koine was the common liturgical language. | |||

{{Col-begin}} | {{Col-begin}} | ||

{{col-n| | {{col-n|3}} | ||

:: Patera mek | :: Patera mek, en eis ta juranak, | ||

:: Az agyasta to noma sei, | |||

:: | :: Az megyérkeszel to vasileu sei, | ||

:: | :: Az gyenn to tilkima sei, | ||

:: | :: Eis gea as enta eis to menny | ||

:: | :: A megbocsát sei ta martÿmatak mek | ||

:: As megbocsátamen davtak p' martana ellen mek. | |||

:: | :: Ce y engedélys mek eis kiszertesz, | ||

:: | :: Ma védens mek ecs to kacka. | ||

:: | :: Amin. | ||

:: | {{col-n|3}} | ||

:: | :: Πατέρα μεκ, εν ιης τα ιουράνακ, | ||

{{col-n| | :: Αζ αγυάστα το νόμα ση, | ||

:: Αζ μέγυεερκεεσ̌ελ το βασηλέβ ση, | |||

:: Αζ γυενν το τήλκημα ση, | |||

:: Ιης γέα ας εντά ιης το μέννυ, | |||

:: Α μέγμποτσ̌αατ ση τα μαρτοϋματακ μεκ, | |||

:: Ας μεγμποτσ̌ααταμεν δάβδακ π΄μαρτάνα έλεν μεκ, | |||

:: Τσε οϋ ένγεδεελυς μεκ ιης κίσ̌ερτες̌, | |||

:: Μα βέεδενς μεκ ετς̌ το κακά. | |||

:: Αμήν. | |||

{{col-n|3}} | |||

<i> | <i> | ||

:: Our Father, who art in heaven, | :: Our Father, who art in heaven, | ||

Latest revision as of 19:40, 20 August 2024

| Grekelin | |

|---|---|

| To gnudzsa Grekelenikin, Rumejkin | |

The Grekelin flag. Largely inspired by the Byzantine design of the time, it signifies the Roman descendance of the Grekelin people. It was adopted formally in 1992 although variations of it were used sparsely in some separatist movements. | |

| Created by | Aggelos Tselios |

| Date | 2023 |

| Native to | Slovakia, Hungary, Serbia |

| Ethnicity | Greeks |

| Native speakers | approx. 200 thousand (2023) |

Early forms | |

Standard form | Standard Modern Grekelin

|

Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | Vojvodina |

| Regulated by | Grekelin Language Administration |

Grekelin (Autoglossonym: Grekelenikin, pronounced: [grɛ.kɛ.ˈɫɛ.ni.kin]), also known as Rhumaecen[3] (Grekelin: Rumejkin, [ɾuˈmɛi̯ˌkin], lit. "The Roman one") is a language derived from Medieval Greek spoken in Vojvodina, Southern Hungary and some isolated villages of Slovakia. Grekelin split from mainland/Anatolian Greek in the late 11th century with the mass settlement of Hungary by Greek refugees following the Seljuk Turks' raids. For the largest part of its existence, Grekelin was mostly a spoken language, and the language began systematically being written down around the 19th century (From where it gained it's modern orthography by Catholic priests and scholars). Due to its low social prestige, most of its educated speakers preferred writing in Latin or Hungarian (Also Koine before the Catholicisation of the Grekelin-speaking people) and few texts were written until then in Grekelin, most of which used the Greek script instead (See Old Grekelin).

As a related language to Greek, Grekelin shares with Modern Greek and its dialects multiple features and cognates. The language, although officially having a free word order, has become an SOV one (As opposed to most Indo-European languages which are SVO) due to extensive Hungarian influence. It's core vocabulary has remained Greek however many Hungarian words can be found often in the language (Especially those relating to law and government), due to the strong adstratum formed by Hungarian (Though, due to geography, the Slavic dialect got its name from its stronger Slavic influence). Grekelin is the most isolated Hellenic language currently in the entire world, with about 1200 kilometers separating it from the closest Greek speaking territory.

Classification

It is not easy to classify Grekelin as a language. Although a Hellenic language, it possibly derives instead from Attic-Ionic dialects spoken in Anatolia (Since the initial settler wave mostly came from Greeks of the area), and, as such, may be more closely related to Pontic than Modern Greek itself, which derives from Koine Greek. The most obvious example is that iotacism never developed in the language (Compare Greek "ήλιος" ([ˈiʎos]) and Grekelin "elya" ([ˈɛʎa]), both meaning "sun"). Hence, Grekelin can be classified as an Indo-European language of the Hellenic branch derived from the Attic-Ionic dialects of Asia Minor.

Grekelin and Tsakonian do seem to share some vocabulary similarities, however these are coincidences and the two have not been at contact almost[4] never.

Phonology

Grekelin's phonology is extensively influenced by Hungarian, and, in the Slavic dialect, by other Slavic languages. The accent varies depending on the location, so this is the standard Grekelin phonology that is used in education and formal speech:

| ↓Manner/Place→ | Place of Articulation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal | Palatal | Velar | |

| Nasal | /m/ | /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | ||

| Stop | /p/ /b/ | /t/ /d/ | /c/ /ɟ/ | /k/ /g/ | ||

| Affricate | /ʥ/ /ʨ/ | |||||

| Fricative | /f/ /v/ | /s/ /z/ | /ɕ/ /ʑ/ | /j/ | /x/ | |

| Approximant | [j˖][5] | |||||

| Tap | /ɾ/ | |||||

| Lateral approximant | /l/ | /ʎ/ | ||||

| Height | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | ||

| High | /i/ | /y/ | /u/ |

| High-mid | (/ø/)* | /o/ | |

| Low-mid | /ɛ/ | ||

| Low | /ɑ/ | ||

* Although it only appears in Hungarian or German loanwords, it is often written down using "ö", so people that write the language consider it a native sound. It is considered more of a marginal phoneme.

Although Grekelin does have diphthongs, they appear rarely and usually merge into one vowel when realized. Most of these diphthongs are not inherited from Greek directly, but developed on their own over the centuries.

| Written diphthong | Common realization | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ai /ɑi̯/ | [ɑː] | fair [fɑːr̩] (Just person) |

| oi /oi̯/ | [y] | anoigyo [aˈnyɟo] (I open) |

| ui /ui̯/ | [uː] | fui [fuː] (Child) |

| eu /ɛu̯/ | [ɛv] | euckola [ˈevkoɫa] (Easily) |

| au /ɑu̯/ | [ɑv] or [aw] | gaunna [ˈgawna] (Tall mountain) |

Grekelin does not favor consonant clusters, often inserting vowels or using metathesis to break them apart. The only exception are affricates since they are considered a single sound in Grekelin.

Although not written, the final consonant (If the word ends with a consonant) always becomes devoiced in colluquial speech.

Alphabet and Orthography

The Grekelin alphabet consists of 24 letters, six of which are vowels and 18 are consonants.

| Letters of the Grekelin alphabet | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa (/ɑ/) | Bb (/b/) | Cc (/t͡s/) | Dd (/d/) | Ee (/ɛ/) | Ff (/f/) | Gg (/g/) | Hh (/x/) | Yy (/y/)[6] | Ii (/i/) | Kk (/k/) | Ll (/ɫ/) | Mm (/m/) | Nn (/n/) | Οο (/o/) | Pp (/p/) | Rr (/r/) | Ss (/s/) | Jj (/j/) | Tt (/t/) | Uu (/u/) | Vv (/v/) | Zz (/z/) | |

The letters correspond always to their pronunciation. The Grekelin orthography is considered a phonetic, as opposed to deep orthographies like French's. In addition, the following digraphs are used within the language:

| Digraphs in Grekelin orthography | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ei (/ji/) | cs - /t͡ɕ/~/t͡ʃ/ | zs - /ʑ/ | sz - /ɕ/) |

Grammar

The grammar of Grekelin is generally very simple and consistent. It is very conservative compared to Greek (Or dialects of it), eg. by retaining the old imperative. The most outstanding feature would probably be that of vowel harmony, which is found at least in both the standard and slavic dialects, and possibly evolved from the extensive Hungarian adstratum.

Articles

Grekelin has both indefinite and definite articles, which are inflected exclusively based on the number and the noun ending.

| Ending | Definite Article | Indefinite Article | Plural Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| -i noun ending | E /ε/ | eni /ˈɛɳi/ | Ek /ek/ |

| Other noun endings | To /to/ | en /ɛɳ/ | Ta |

Cases

Grekelin has 4 cases: Nominative, genitive, accusative and vocative. In the Slavic dialect, another case exists, the dative case. Grekelin has developed vowel harmony in the language so while the endings here are influenced by the nearby vowels, other words may have different inflections. While genders in Grekelin are considered extinct, remnants of it exist in the noun endings (a or i/e), so Grekelin is considered to have a separate noun class system that merged with the Indo-European one.

| Case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | To gnudzsa | Ta gnudzsuk |

| Genitive | C' gnudzsus | Ta gnudzsun |

| Accusative | Ecs gnudzsan | Ecs gnudzsun |

| Vocative | O gnudzse | Oh gnudzsen |

Nouns ending in -i are slightly different but overall not very hard:

| Case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | E kukli | Ek kukljuk |

| Genitive | c' Kuklu | Co kuklun |

| Accusative | Ecs kuklin | Ecs kukljuk |

| Vocative | O kukli | Oh kukljuk |

Verbs

Verbs in Grekelin are split into three classes: Weak, strong and irregular. Their classification depends on the last vowel of the word's root (The word without any prefixes and suffixes conveying grammatical information) while the irregulars are outliers in both with their own inflections. The vowels defining strong verbs are /e i y/ and the vowels defining weak verbs are /a o u ø/. The verb class defines the way a word will be inflected for number, tense and mood. Below are two tables showing the present tense inflection for a weak and a strong verb:

Strong Verbs

| Pronoun | Verb Declension |

|---|---|

| Go | Vlemm-o |

| Szÿ | Vlemm-s |

| Davta | Vlemm |

| Mis | Vlemm-men |

| Szÿk | Vlemm-te |

| Davtak | Vlemm-ne |

Weak Verbs

| Pronoun | Verb Declension |

|---|---|

| Go | Jebor-o |

| Szÿ | Jebor-as |

| Davta | Jebor-a |

| Mis | Jebor-amen |

| Szÿk | Jebor-ate |

| Davtak | Jebor-anda |

Geographic Distribution and Demographics

Grekelin today has about 100 thousand speakers, spread out in Hungary, Serbia and a tiny minority in Slovakia. It forms the majority language in villages of North Banat and some spread out parts of Slovakia. It forms a significant language in Hungary (where the standard dialect evolved too). The populations of Serbia and Slovakia speak the Slavic dialect whereas the Hungarian population speaks the Standard dialect, although the dialect does not change by the border.

Evolution

Vowels

Grekelin preserved all Medieval Greek vowels (Thanks to shared phonology with Hungarian). Depending on the dialect, vowel length did evolve (Usually where the stress fell), however Standard Grekelin does not enforce vowel length distinction in any vowel. ('íosz' (son) and 'iosz' (death) are the same except for the first vowel, which is a long one in son). The phoneme /ø/ eventually entered Grekelin from Hungarian loanwords and can now be found exclusively in those loanwords.

Little historical changes occured in vowels. The two most common ones are:

- The raising of unstressed /o/ to /u/, unstressed /e/ to /i/ and unstressed /a/ to /y/. The last two only occured in dialects.

- Consonants behind /i/ and /e/ become palatalized (softened), except when these vowels are stressed or come before the stressed vowel.

Unlike Greek, Byzantine Greek /y/ did not collapse to /i/ like all other Greek dialects except for Old Athenian (and Tsakonian). By extension, consonants become aspirated before /y/.

Consonants

Grekelin completely eliminated almost all consonant clusters, either through metathesis or through the insertion of a vowel when there could be vowel harmony in that word, eg. Greek Αλεύρι vs Grekelin Alevir. Apart from the palatalization mentioned above, there was no major sound change in Grekelin's consonants, except for the fortition that took place later: Grekelin had inherited the fricatives /θ x ð ɣ/ from Greek's previously softened /tʰ kʰ d g/, however that change was reversed around the 18th century when /θ x ð ɣ/ merged with /tː k͡x d g/ (Later further merged into /t x d g/).

Vocabulary

Grekelin has about 60.000 words in total, with another 15.000 obsolete ones, amounting to 75.000 words in total. Most of Grekelin's vocabulary is derived from Greek directly, and very few Greek borrows (Mostly reborrows) actually exist within the language. There is an estimated 20 to 40% Hungarian-borrowed vocabulary, depending on the dialect and the person themselves. In the Slavic dialects there is a strong Slavic influence (hence the name), which also shows in the vocabulary part; Between 5% and 25% of all words in Grekelin come from Slavic dialects. The remaining 5% that doesn't belong in any of these categories is either German, Turkic or does not have any clear etymology, like the word leotti. Some theorize Grekelin was in contact with Pannonian Avar speakers which may provide explanation for some of the strange words in Grekelin.

Words

Numbers

| English | Grekelin | Pronunciation (IPA) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Miden | [mʲiˈdɛn] |

| 1 | Ena | [ˈɛna] |

| 2 | Djo | [djo] |

| 3 | Tria | [ˈtɾia] |

| 4 | Tessera | [ˈtɛsʲeɾa] |

| 5 | Pende | [ˈpɛndʲe] |

| 6 | Ess | [ɛs] |

| 7 | Efta | [ɛˈftɑ] |

| 8 | Uchta | [uˈxtɑ] |

| 9 | Enya | [ɛˈɲɑ] |

| 10 | Decka | [ˈdɛka] |

Conversation

| English (Egzlezikin) | Grekelin (Grekelenikin) | Pronunciation (IPA) |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | Ne | /nɛ/ |

| No | Y | /y/ |

| Hello! | Dzsóvorzo! (Formal) / Gya! (Informal) | /'d͡ʑovorzo/ /ɟɑː/ |

| Good morning! | Dzso regetti! | /d͡ʑo rɛ.ˈgɛ.ti/ |

| Good night! | Dzso niktrá! | /d͡ʑo nik'trɑ/ |

| Have a nice day! | Eis dzsódοla sei! | /jis 'd͡ʑodolɑ si/ |

| Goodbye! | Visondlataszra | /'visontɭatɑːɕr̩a/ |

| Thank you! | Dzsómmo! | /ˈd͡ʑomo/ |

| Who? | Pkios? | /pki̯os/ |

| What? | Ti? | /ti/ |

| When? | Ponte? | /ˈpo.ndɛ/ |

| Where? | Pe? | /pɛ/ |

| How? | Posz? | /ˈpoɕ/ |

| Why | Dzatti? | /'d͡zɑti/ |

| Again | Ura | /uˈrɑ/ |

| What is your name? | Ti entá a nóma sei? | /ti ɛnˈta ɑ ˈno.mɑ sʲi/ |

| My name is... | A noma mei enta ...' | /ɑ ˈno.ma mʲi enˈtα/ |

| Do you speak English? | Relalíte eís to Egglézikin? | /rɛ.ɫɑˈɫite jis to ɛkˈɫɛ.zikiŋ/ |

| I do not understand Grekelin. | Y nyó a gnúdzsa Grekelénikin. | /y ɲo ɑ ˈɡnud͡ʑɑ ɡrɛˈkɛ.ɫɛnikin/ |

| Help me! | Voettja! | /ˈvoˈtʲɑ/ |

| How much is it? | Pószo entá? | /ˈpoɕo ɛnˈtɑ/ |

| The study of Grekelin sharpens the mind. | Mattisi c'Grekelenikis fjann' to essa kovtoérta. | /'matkisi t͡si grɛkɛˈɫɛ.nikis pjɑ α ˈɛ.sa kovtoˈɛr.ta/ |

| Where are you from? | Pe este ecs szÿ? | /pɛ ˈɛste ɛt͡ɕ ɕy/ |

Dialects

While Old Grekelin was evolving into the modern Grekelin language, regional, social and stratum factors were influencing Grekelin in many degrees. Old Grekelin had 4 dialects: The Western-Vienna, the Danubian, the Southern and the Savvian dialect. No descendants exist of the first and the last dialects, although the former provided some loanwords to Grekelin and made it to the 19th century. For the sake of history all three dialects will be mentioned in this section.

Danubian

The Danubian dialect is the one spoken in southern Hungary and the base of the standard literary language. It shares most of the Grekelin speakers and it's the one used in education and formal speech. It developed out of homonymous Old Grekelin dialect, having split from the Southern (Slavic) dialect around the 13th century.

Slavic Dialects

The Slavic dialects are split into two subgroups: Northern and Southern. The two are not shared by genetic relationship as the Northern branch split from a blend of Danubian and Slavic speakers during the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent immigration. The northern branch is going extinct today, and can be characterized by a heavy Czech/Slovak influence. The Southern branch on the other hand is thriving south of the Danubian dialect, being an official language of Vojvodina.

Northern Branch

The northern branch has evolved /o/ to /ɔ/ and /y/ to /ɨ/. It also uses an alveolar trill as the main rhotic instead of the southern branch's tap. It also merged weak and strong verb classes into one, similar to Western Grekelin.

Southern Branch

The southern branch is close to the Danubian dialect, largely because the two have constantly been at contact. The most prominent feature is the iotation of word-initial vowels (Danubian dialects also contain this feature, but only for the /e u/ vowels) and the lack of aspiration for consonants before /y/.

Western Dialect

The Western dialect went extinct in the 19th century. It was an evolution of Old Grekelin's Western dialect, itself having split from Danubian Grekelin around the 16th century. When the two dialects reentered linguistic contact after the siege of Vienna, many German loanwords entered through it the Danubian dialect. It went extinct eventually as its speakers either switched to German/Hungarian or adopted the Danubian dialect instead.

The most interesting sound change to occur in Western Grekelin was the reduction of plain /a/ to /æ/ and later /ə/ when unstressed. Some subdialects further reduced /o/ to /ɒ/ and then /ɐ/ although that change was only limited to a small area. Apart from those, very little divergence existed from the Danubian Grekelin; Most speakers didn't realize they spoke different dialects without extensive exposure to each other's speech. This is mostly attributed to Western Grekelin becoming a very isolated dialect with little outside influence, mostly limited to trade.

Example texts

Basic sentence

English

I would like a coffee and biscuits, thank you.

Grekelin

(Go) tílko eni kave kia biszkotek, dzommo.

UN Human Rights Declaration, Article 1

English:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Grekelin:

Padi eleottek eleszterek kya memisek evortamek eis meltosagi kya jogatek. Demdorizandek mi eszelin kya sÿnindisin, kya prepi a ecsinalamek en eis allila eis en selemi c' aderfiktas.

[ˈpa.dʲi ɛlɛˈo.tek ɛˈlɛɕtɛˌrɛk ca meˈmʲisɛk ɛˈvortamʲɛk jis ˈmɛɬto.ˌsaɟi ca ˈjogatʲek ‖ demˈdorizaˌndɛk mi ˈɛɕɛɫin kʲa synʲindʲisʲin ca prʲepʲi na ɛt͡ɕiˈnɑlnamʲek ɛn jis ˈalʲiɫa jis ɛn ˈɕɛlʲɛmʲi t͡s aˈderfʲiktas]

Lord's prayer

In liturgical usage, Grekelin is rarely a preferred language. The prayers are usually in Hungarian or Serbian, however villages with proportionally larger Grekelin population use a slightly modified form of the lord's prayer, written below. In previous centuries, Latin was also fairly common, and, before the conversion of Grekelin people to Catholicism, Koine was the common liturgical language.

|

|

|

Notes

- ^ If indeed Cappadocian Greek started out as a dialect of Pontic Greek (Which isn't descended from Koine but directly from Attic-Ionic dialects), then so did Grekelin since they share their urheimat in the south of Anatolia. That would easily explain why Grekelin has /e/ in place of Modern Greek /i/.

- ^ Grekelin and Cappadocian have a common ancestor with the difference that Cappadocian remained spoken in Anatolia whereas Grekelin was brought to it's modern territory by migration and settlement. And, outside of roleplay in the context of this article, it's where most of the study related to Grekelin falls into, because Turkish and Hungarian share many features. However, as you can understand, Cappadocian at that point would've been plain regular Greek (Possibly a dialect of Pontic? See the article for details), hence the question mark.

- ^ Grekelin split from Greek at a time where the Greek population considered themselves Roman (Due to the Byzantine Empire and Christianity) and the native name for the language is actually Rhumejkin. The name Grekelin is an exonym by Slavs and Hungarians.

- ^ The Propontis dialect of Tsakonian may've been in contact with Pre-Grekelin (the dialects spoken by the Grekelin settlers before Grekelin emerged) as some of the settlers may have been native speakers of Tsakonian. Even so, the influence of Tsakonian in Grekelin is very small to be considered a significant influence.

- ^ The voiced alveolo-palatal approximant (A sound somewhat similar to /j/) does exist in Grekelin as an allophone of /j/ behind rhotics and laterals. It is the only language, along with Huastec, to include it.

- ^ Styled after Hungarian, Grekelin often uses "y" to show that the preceding consonant is palatalized. When 'y' is to actually be pronounced as a vowel but it is preceded by a consonant, it takes a dieresis above it: eg. "GŸ gÿ".