Minhast/Dialectology: Difference between revisions

Added 1st person possessor to clan ("my clan") |

|||

| (54 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

== Dialectal Divisions == | == Dialectal Divisions == | ||

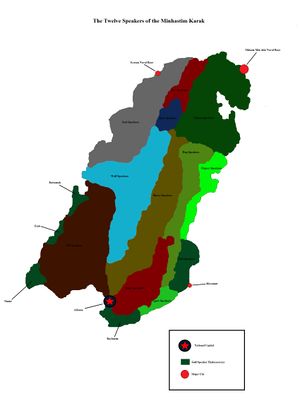

[[File:Map of the Twelve Speakers of Minhay.jpg|thumb|Map of the Twelve Speakers of Minhay]] | [[File:Map of the Twelve Speakers of Minhay.jpg|thumb|Map of the Twelve Speakers of Minhay]] | ||

Minhast is divided into fourteen dialects, twelve of which are the historical dialects spoken in the Prefectures, and two new dialects that have arisen in modern times, a standardized "national" dialect, and an urban colloquial dialect. | Minhast is divided into fourteen dialects, twelve of which are the historical dialects spoken in the Prefectures, and two new dialects that have arisen in modern times, a standardized "national" dialect, and an urban colloquial dialect. Two additional dialects, the Knife Speaker dialect, and the Heron Speaker dialect<sup>1</sup>, are now extinct. The Knife Speaker dialect is poorly attested. | ||

The dialects of the Prefectures have been traditionally grouped under two branches, Upper Minhast, and Lower Minhast. Within Upper Minhast, a further dialectal split emerged, leading to the Salmon Speaker and Wolf Speaker dialects. Minhast grammarians have traditionally classified the dialects according to the following phylogeny: | The dialects of the Prefectures have been traditionally grouped under two branches, Upper Minhast, and Lower Minhast. Within Upper Minhast, a further dialectal split emerged, leading to the Salmon Speaker and Wolf Speaker dialects. Minhast grammarians have traditionally classified the dialects according to the following phylogeny: | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Upper Minhast, which consists of several dialects in the northern highlands, encompasses the Northern Coast, Northeastern Mountain Coastal Range (''Gaššarat'', lit. "basalt"), the Kilmay Rī Mountain Range, the Central Plateau ''(Kammak min Nukya)'', and the the Great Plains (''Hamhāmarū'' , lit. "The Great Clearing of the Grasses"). Lower Minhast traditionally has been the branch containing the dialects south of the tribal territories (''karak'') of the Dog, Salmon and Horse Speakers. The ''uyyi min kirim'', lit. "The (way) of saying the (sequence) ''-uyyi''" is the primary test in determining which branch a given dialect should be grouped under, although other tests may be employed as well, such as the frequency of loanwords from the unrelated minority languages Peshpeg and Golahat, and a recently discovered, extinct non-Minhastic language called Corradi; the dialects of the Upper Minhast branch have virtually no loanwords from these languages, whereas the dialects of Lower Minhast branch have such loans in varying degrees. The Palatization Test is also used to classify dialects: the dialects from the Lower Minhast branch palatize /t/ and /d/ to [t͡ʃ] and [d͡ʒ] when followed by /j/, /ia͡/ or /ie͡/, a feature lacking in the dialects of the Upper Minhast branch. | Upper Minhast, which consists of several dialects in the northern highlands, encompasses the Northern Coast, Northeastern Mountain Coastal Range (''Gaššarat'', lit. "basalt"), the Kilmay Rī Mountain Range, the Central Plateau ''(Kammak min Nukya)'', and the the Great Plains (''Hamhāmarū'' , lit. "The Great Clearing of the Grasses"). Lower Minhast traditionally has been the branch containing the dialects south of the tribal territories (''karak'') of the Dog, Salmon and Horse Speakers. The ''uyyi min kirim'', lit. "The (way) of saying the (sequence) ''-uyyi''" is the primary test in determining which branch a given dialect should be grouped under, although other tests may be employed as well, such as the frequency of loanwords from the unrelated minority languages Peshpeg and Golahat, and a recently discovered, extinct non-Minhastic language called Corradi; the dialects of the Upper Minhast branch have virtually no loanwords from these languages, whereas the dialects of Lower Minhast branch have such loans in varying degrees. The Palatization Test is also used to classify dialects: the dialects from the Lower Minhast branch palatize /t/ and /d/ to [t͡ʃ] and [d͡ʒ] when followed by /j/, /ia͡/ or /ie͡/, a feature lacking in the dialects of the Upper Minhast branch. | ||

=== "The Twelve Speakers" === | === "The Twelve Speakers" Classification System === | ||

{| class="bluetable lightbluebg" | {| class="bluetable lightbluebg mw-collapsible" | ||

|+ '''Traditional Classification of the Twelve Historical Dialects''' | |+ '''Traditional Classification of the Twelve Historical Dialects''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

| Umbarak, Hayreb, Nanampuyyi, Wattare, Saxtam, Gannasia, Rummak , Iyyay, Hattūmi, Nu'ay, and Xirrim Prefectures; <br/> | | Umbarak, Hayreb, Nanampuyyi, Wattare, Saxtam, Gannasia, Rummak , Iyyay, Hattūmi, Nu'ay, and Xirrim Prefectures; <br/> | ||

Āš-min-Gāl, Ankussūr, Huruk, Nammadīn, Kered, and Kattek (NW Quadrant of NCR, approx 60%) | Āš-min-Gāl, Ankussūr, Huruk, Nammadīn, Kered, and Kattek (NW Quadrant of NCR, approx 60%) | ||

| Fossilized affix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-uyyi'' | | | ||

*Preservation of final /n/ in Transitive terminative affix ''-un'' | |||

*Fossilized affix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-uyyi'' | |||

*Realization of /rx/ as [ɣ] | |||

*Syllables containing /a/ trigger progressive vowel harmonization of <br/> /I, i, ɛ, e/ to /a/ | |||

V + /ħħ/ triggers lengthening of initial vowel and degemination of pharyngeal: VV + /ħ/ | *V + /ħħ/ triggers lengthening of initial vowel and degemination of <br/> pharyngeal: VV + /ħ/ | ||

*Preservation /wi/, which has merged into /ʔu/ in most dialects | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Terminatives zone | |||

Fossilized suffix ''-at'', ''-āt'', ''-mat'' and ''-māt'' (cognates of Salmonic dialects' | *Locative noun formed using Locative Applicative ''-naħk-'' + verb root (+ Nominalizer ''-naft'') | ||

*Pervasive use of the Interrogative-Polarity discourse particle ''ni/nī'' | |||

*Fossilized suffix ''-at'', ''-āt'', ''-mat'' and ''-māt'' <br/>(cognates of Salmonic dialects' ''-bāt'', ''-mbāt'', ''-umbāt'') are retained | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 43: | Line 50: | ||

| Hittaħm, Iskamharat, Tuhattam, Perim-Sin, Attum Attar, Yikkam min Akk, Ruyāya Prefectures; <br/> | | Hittaħm, Iskamharat, Tuhattam, Perim-Sin, Attum Attar, Yikkam min Akk, Ruyāya Prefectures; <br/> | ||

Iyyūmi (Salmon Speaker suburb in NCR, approx 80%) | Iyyūmi (Salmon Speaker suburb in NCR, approx 80%) | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' preserved | | | ||

*Preservation of final /n/ in Transitive terminative affix ''-un'' | |||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' preserved | |||

*Initial /ħ/ preserved when followed /a/ | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Terminatives zone | |||

*Alternative locative noun formed using verb root + IN ''-tappe-'', e.g. ''gubbattappe'' "battlefield" | |||

Preponderance of fossilized suffix ''-bāt'' and allomorphs ''-mbāt'', ''-umbāt'' | *Preponderance of fossilized suffix ''-bāt'' and allomorphs ''-mbāt'', ''-umbāt'' | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Hašlua min Kirmast "Wolf Speaker" | ! Hašlua min Kirmast "Wolf Speaker" | ||

| North Central, and Southern Kilmay Rī Mountains, Ešked, Tayyagur, Raqwar, Tabuk Prefectures; Ehar Township | | North Central, and Southern Kilmay Rī Mountains, Ešked, Tayyagur, Raqwar, Tabuk Prefectures; Ehar Township | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' preserved | | | ||

*Preservation of final /n/ in Transitive terminative affix ''-un'' | |||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' preserved | |||

*Initial /ħ/ preserved when followed /a/ | |||

*Phonemes /q, χ/ have developed from both the influence of the Seal Speaker dialect, and a sound shift triggered by regressive consonantal harmony triggered by an adjacent /r/, c.f. Common Minhast /karak/ "tribal territory" vs. Wolf Speaker /qaraq/. The sound shift is particularly noticeable in the northwestern prefectures of the Wolf Speaker ''karak''. | |||

*Locative noun formed using verb root + ''-anki'' suffix, e.g. ''gubbatanki'' "battlefield" | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Terminatives zone | |||

*Preponderance of fossilized suffix ''-bāt'' and allomorphs ''-mbāt'', ''-umbāt'' | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 63: | Line 84: | ||

| Hisašarum, Way, Išpa, Warat, Tabbakun, Hara, Nassaškub, Neweyya, Uħpar, Nikwat, Salabūr, Tawāheb Prefectures;<br/> | | Hisašarum, Way, Išpa, Warat, Tabbakun, Hara, Nassaškub, Neweyya, Uħpar, Nikwat, Salabūr, Tawāheb Prefectures;<br/> | ||

Bussum Demilitarized District | Bussum Demilitarized District | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-uyye'' | | | ||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-uyye'' | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Terminatives zone | |||

|- | |- | ||

! Nurrappam Kirmast "Bear Speaker" | ! Nurrappam Kirmast "Bear Speaker" | ||

| Tannumay, Puyya Prefectures | | Tannumay, Puyya Prefectures | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-uyya'' | | | ||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-uyya'' | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Terminatives zone | |||

|- | |- | ||

! Yattaxmin Kirmast "Fox Speaker" | ! Yattaxmin Kirmast "Fox Speaker" | ||

| Kardam, Eħħar, Yussuk Prefectures | | Kardam, Eħħar, Yussuk Prefectures | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-uyye'' | | | ||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-uyye'' | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Terminatives zone | |||

|- | |- | ||

! Naggikim Kirmast "Elk Speaker" | ! Naggikim Kirmast "Elk Speaker" | ||

| Meti, Attuar, Essak Prefectures | | Meti, Attuar, Essak Prefectures | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ūwe'' | | | ||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ūwe'' | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Terminatives zone | |||

|- | |- | ||

! Hurkadim Kirmast "Seal Speaker" | ! Hurkadim Kirmast "Seal Speaker" | ||

| Pinda, Rukpu Prefectures | | Pinda, Rukpu Prefectures | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ūwi'' | | | ||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ūwi'' | |||

*Occurence of phonemes /q, χ/ | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Terminatives zone | |||

|- | |- | ||

! rowspan="4" | Lower Minhast | ! rowspan="4" | Lower Minhast | ||

| Line 85: | Line 117: | ||

| Kissamut, Tur'akkam, Senzil, Rēgum Prefectures; <br/> | | Kissamut, Tur'akkam, Senzil, Rēgum Prefectures; <br/> | ||

Bayburim, Talwasr/Talwāz, Uğabal (MSM: ''Urgabal''), Tantanay, Nuwway, Kitamta, Antuwe, Sašlar (South Coast Colonies) | Bayburim, Talwasr/Talwāz, Uğabal (MSM: ''Urgabal''), Tantanay, Nuwway, Kitamta, Antuwe, Sašlar (South Coast Colonies) | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-we'', ''-ue'', ''-ia'' | | | ||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-we'', ''-ue'', ''-ia'' | |||

Palatization Test is inconclusive due to dialectal mixing with their Dog, Osprey, and Egret Speaker neighbors: some Gull Speaker words fail the test, while others pass | *Palatization Test is inconclusive due to dialectal mixing with their Dog, Osprey, and Egret Speaker neighbors: some Gull Speaker words fail the test, while others pass | ||

*''Asr̥-Z''-type sandhi: word-final /sr̥/ mutates to /z/, sometimes accompanied by lengthening of previous vowel, e.g. ''kuyuntāz'' "seaweed", c.f. Salmon Speaker ''kiyuntasr'' | |||

*Wholesale replacement of /f/ with /x/, e.g. ''puħtanaxt'' vs Common ''puħtanaft'' "the one standing" | |||

*Realization of /rg/ as [ɣ], e.g. ''Anyāğ'' (from Stone Speaker ''Āhan Yārg'', the premier city-state in Stone Speaker Country) | |||

*Habitative Affix ''-usun-'' | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Terminatives zone, differing wildly from other dialects (e.g. Upper Minhast group) which also have post-verb root deictic affixes: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

* Proximal: ''-nussar-'' | |||

* Medio-proximal: ''-yaiyar-'' | |||

* Distal: ''-ppaiyar-'' | |||

* Invisible: ''-ruššar-'' | |||

</blockquote> | |||

Locative noun derived by adding | *Locative noun derived by adding deverbal locative suffix ''-rū'' to verb stems, which often geminates while triggering assimilation of any preceding consonant, e.g. ''gubbarrū'' "battlefield", c.f. Salmonic ''gubbattappe''; this suffix is found in no other dialect, possibly a borrowing from a substrate language | ||

Presence of fossilized suffixes ''-met'' and ''-mut'', cognate with Horse Speaker ''-at'', ''-āt'', ''-māt'', and Salmonic dialects' | *Presence of fossilized suffixes ''-met'' and ''-mut'', cognate with Horse Speaker <br/>''-at'', ''-āt'', ''-māt'', and Salmonic dialects' ''-bāt'', ''-mbāt'', ''-umbāt'' | ||

Contains several Korean loanwords or calques due to extensive trade contacts with the Kingdom of Koguryeo, e.g. ''humbuk'' < Kr. 한복 ''hanbok'' (Korean-style clothing), ''binyū'' < Kr. 비녀 ''binyeo'' "hairpin" | *Contains several Korean loanwords or calques due to extensive trade contacts with the Kingdom of Koguryeo, e.g. ''humbuk'' < Kr. 한복 ''hanbok'' (Korean-style clothing), ''binyū'' < Kr. 비녀 ''binyeo'' "hairpin" | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Neyūn min Kirmast "Osprey Speaker" | ! Neyūn min Kirmast "Osprey Speaker" | ||

| Uyyuš, Arinak, Naggiriyan, Nāz, Dayyat, Urria Prefectures | | Uyyuš, Arinak, Naggiriyan, Nāz, Dayyat, Urria Prefectures | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ia'' | | | ||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ia'' | |||

Past Tense ''-ar-'' and Imperfect Aspect ''-ab-'' affixes merge to the Past Imperfect Tense-Aspect marker ''-arb-''/''-rb-''; | *Past Tense ''-ar-'' and Imperfect Aspect ''-ab-'' affixes merge to the Past Imperfect Tense-Aspect marker ''-arb-''/''-rb-''; | ||

Marker ''-tunt-'' replaces ''-nta-'' for Intensive | *Marker ''-tunt-'' replaces ''-nta-'' for Intensive | ||

Lexicon contains large number of Salmon Speaker words | *Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Preverbal zone | ||

*Lexicon contains large number of Salmon Speaker words | |||

|- | |- | ||

! Šunnekim Kirmast "Egret Speaker" | ! Šunnekim Kirmast "Egret Speaker" | ||

| Nentie, Isku Prefectures | | Nentie, Isku Prefectures | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ie'' | | | ||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ie'' | |||

*Marker ''-tint-'' replaces ''-nta-'' for Intensive | |||

*Past Tense ''-ar-'' and Imperfect Aspect ''-ab-'' affixes merge to the Past Imperfect Tense-Aspect marker ''-arb-''/''-rb-'' | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Preverb zone | |||

|- | |- | ||

! Banakim Kirmast "Stone Speaker" | ! Banakim Kirmast "Stone Speaker" | ||

| Sakkeb, Neskud,Yaxparim, Izgilbāš, Zurzugul, Higbilan, Narpaz Prefectures | | Sakkeb, Neskud,Yaxparim, Izgilbāš, Zurzugul, Higbilan, Narpaz Prefectures | ||

| Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ī'' | | | ||

*Fossilized suffix ''-ūy'' realized as ''-ī'' | |||

*Development of allophone [o] from /u/ in CVCC syllables or in word-final position, e.g. ['uʃno],, ['oʃno], c.f. Common /'uʃnu/ "to hit, strike" | |||

*Merger of /aw:a, a:wa/ to /o/ , e.g. /'kowat/ "iron", c.f. Common /kaw:at/ "steel" | |||

*Frequent dropping of ''-n'' suffix of intransitive affix ''-an'', e.g. /'aʃ:ija/ "to sit" (c.f. Common /'saʃ:ijan/) | |||

*Word-initial /s/ becomes either /h/ or /Ø/, e.g. /'aʃ:ija/ "to sit", c.f. Common /'saʃ:ijan/ | |||

*Ergative marker ''=de'' is often dropped if the polypersonal agreement markers can disambiguate Agent from Patient | |||

Large inventory of non-Minhast loanwords from Peshpeg, Golahat, and the newly discovered Corradi language (in combination, approximately 20% of the lexicon); the average number of loanwords in the other Lower Minhast dialects range from 3% to 5% | *Much freer word order - the verb often deviates from the verb-final position whereas the other dialects allow the verb to migrate to non-final position within a clause only under very strict constraints | ||

*Habitative Affix ''-sun-'' | |||

*Locational/deictic verbal affixes appear in the Preverb zone | |||

*Large inventory of non-Minhast loanwords from Peshpeg, Golahat, and the newly discovered Corradi language (in combination, approximately 15% to 20% of the lexicon); the average number of loanwords in the other Lower Minhast dialects range from 3% to 5% | |||

|} | |} | ||

=== The Modern Dialects === | === The Modern Dialects === | ||

Two new dialects have both arisen in the National Capital Region (NCR). Modern Standard Minhast, a conglomeration of the Upper Minhast and Lower Minhast dialects, as well as Classical Minhast, serves as the standard dialect used for government, commerce, and media. Despite that more than half of its lexicon is of Lower Minhast origin, the dialect is classified as part of the Upper Minhast branch due to its grammar, which is largely drawn from the Dog Speaker dialect. The National Academy of the Minhast Language serves as the official body in creating and maintaining the standardized form of the language and biannually publishes the ''Minhastim Kirim min Suharak'' (Dictionary of the Minhast Language). In spite of its official status, the adoption of Modern Standard Minhast by the Prefectures has been limited due to resistance from the local speech communities. The second dialect, known as the City Speaker dialect (aka Modern Colloquial Minhast), is an admixture of several dialects; although most of the lexicon comes from the dialects of the Common Branch, many Stone Speaker words from the Montaigne branch have been imported. Nevertheless the grammar is ultimately derived from the Common branch. The City Speaker dialect is centered in the official capital, Aškuan. This dialect contains more loanwords from foreign languages than the standard language, especially in areas of technology and the Internet, international sports, and from foreign films and media. The City Speaker dialect allows CCC consonant clusters in medial syllabic positions, while only final CC clusters are allowed. Initial CC clusters are also possible for a limited set of combinations, e.g. /kw/, /kr/, /kl/, /sm/, /sn/, /šm/,/šn/, /sl/, /šl/ . This new dialect is also replete with slang, loanwords (especially from Western sources) and nonstandard jargon that is often looked down upon by Speakers from the more conservative Prefectures. | |||

== Intelligibility == | == Intelligibility == | ||

Mutual intelligibility between dialectal groups is affected by several factors. As a whole, the Upper Minhast group is regarded as more conservative in phonology and grammar compared to the Lower Minhast group, but even within each group there may be great differences in the lexicon arising oftentimes from differences in environment and lifestyle that may affect intelligibility. For example, the extremely conservative Salmon Speaker dialect has nevertheless developed a specialized vocabulary for terminology reflective of their riverine and coastal environment, while the Horse Speakers lack such terminology for the simple reason that their homeland is landlocked. Moreover, dialectal mixing is the norm, not the exception. The Gull Speakers, although grouped as a Lower Minhast dialect, can communicate with the Dog Speakers, who belong to the Upper Minhast branch, with little difficulty. This is because both Speakers share a common border and have long had extensive trade contacts with each other which have leveled lexical differences. The Osprey Speakers find the Stone Speakers | Mutual intelligibility between dialectal groups is affected by several factors. As a whole, the Upper Minhast group is regarded as more conservative in phonology and grammar compared to the Lower Minhast group, but even within each group there may be great differences in the lexicon arising oftentimes from differences in environment and lifestyle that may affect intelligibility. For example, the extremely conservative Salmon Speaker dialect has nevertheless developed a specialized vocabulary for terminology reflective of their riverine and coastal environment, while the Horse Speakers lack such terminology for the simple reason that their homeland is landlocked. Moreover, dialectal mixing is the norm, not the exception. The Gull Speakers, although grouped as a Lower Minhast dialect, can communicate with the Dog Speakers, who belong to the Upper Minhast branch, with little difficulty. This is because both Speakers share a common border and have long had extensive trade contacts with each other which have leveled lexical differences. The Osprey Speakers find the Stone Speakers virtually unintelligible even though both are grouped under the Lower Minhast branch; in fact Osprey Speakers report they can converse much more easily with the Wolf Speakers, an Upper Minhast dialect, despite the Wolf Speaker dialect's conservative features and affiliation with the Upper Minhast branch. The Osprey Speakers territories border Salmon Speaker Country; they too have had extensive trade relations with the Salmon Speakers and as a consequence both groups can understand each other despite belonging to two different branches. Bilingualism is common, and diglossia from usage of the prestige language, Classical Minhast, also complicates the linguistic landscape. | ||

As an illustration of the dialectal differences, sample texts are provided below. They all mean, "Yes, (these are) the markings of my clan": | As an illustration of the dialectal differences, sample texts are provided below. They all mean, "Yes, (these are) the markings of my clan": | ||

| Line 162: | Line 212: | ||

}} | }} | ||

Salmon Speaker: | |||

{{Gloss | {{Gloss | ||

| Line 169: | Line 219: | ||

| morphemes = ēlā huzzakteš-kenk=de min baktet-makkem=de | | morphemes = ēlā huzzakteš-kenk=de min baktet-makkem=de | ||

| gloss = yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG | | gloss = yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG | ||

| translation = | |||

}} | |||

Horse Speaker: | |||

{{Gloss | |||

|phrase = Ħallā, ħuzzaktuškankada num baktumtakkammada. | |||

| IPA = | |||

| morphemes = ħallā ħuzzaktuš-kank=da min baktut-makkam=da | |||

| gloss = yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG | |||

| translation = | |||

}} | |||

Dog Speaker: | |||

{{Gloss | |||

|phrase = Eyla, huzzaktiškenkemin baktentakkent. | |||

| IPA = | |||

| morphemes = ēlā huzzaktiš-kenk=de=min baktet-makkem=de | |||

| gloss = yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG =ONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG | |||

| translation = | | translation = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 195: | Line 265: | ||

{{Gloss | {{Gloss | ||

|phrase = La', hizzakiškentim | |phrase = La', hizzakiškentim baktettakkent. | ||

| IPA = | | IPA = | ||

| morphemes = la' hizzakš-kenk=te=im baktet-nakken=te | | morphemes = la' hizzakš-kenk=te=im baktet-nakken=te | ||

| Line 205: | Line 275: | ||

{{Gloss | {{Gloss | ||

|phrase = | |phrase = Ia, zaguškunkun bekummunkuk. | ||

| IPA = | | IPA = | ||

| morphemes = | | morphemes = ia zakš-kun=k=un bekut-munk=k | ||

| gloss = yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG=CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG | | gloss = yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG=CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG | ||

| translation = | | translation = | ||

}} | }} | ||

* The ergative in the examples above also serves as a genitive marker, as in Yup'ik. | * The ergative in the examples above also serves as a genitive marker, as in Yup'ik. | ||

* The Upper Minhast dialects, as can be seen in this text sample, show the greatest amount of conservatism, and all are mutually intelligible with each other, although the Dog Speaker dialect has diverged enough such that speakers of the other Upper Minhast dialects report difficulties in understanding it. | * The Upper Minhast (Salmon, Horse, and Dog Speaker) dialects, as can be seen in this text sample, show the greatest amount of conservatism, and all are mutually intelligible with each other, although the Dog Speaker dialect has diverged enough such that speakers of the other Upper Minhast dialects report difficulties in understanding it. | ||

* Modern Standard Minhast (MSM) is closest, at least in | * Modern Standard Minhast (MSM) is closest, at least in morphology and syntax, to the Dog Speaker dialect<ref>More specifically, the variety as spoken in Tagna Prefecture, as can be seen from the ''-m-'' → ''-n-'' morphophonemic alternation when the pronominal affix combines with the ergative/genitive clitic, which differs from most Dog Speaker dialects.</ref>. However, monolingual Dog Speakers consider the national language difficult to understand, because over half of its lexicon is drawn from Lower Minhast sources, and some phonological rules which govern the allomorphs of certain affixes and clitics, such as the ergative ''=de'', can differ significantly between the two dialects. | ||

* For whatever reason, the Osprey speakers treat ''baktet'' "tattoo" as an animate noun. | * For whatever reason, the Osprey speakers treat ''baktet'' "tattoo" as an animate noun. Intra-dialectal gender discordance is common. | ||

* The Gull Speaker text shows some features found in the Upper Minhast text, and others in the Osprey Speaker text. Features in the Gull Speaker text not found in the other texts are the underlying form of the polypersonal agreement affix ''-unkem-'', and the surface realization of the Ergative clitic after sandhi processes have been applied. | * The Gull Speaker text shows some features found in the Upper Minhast text, and others in the Osprey Speaker text. Features in the Gull Speaker text not found in the other texts are the underlying form of the polypersonal agreement affix ''-unkem-'', and the surface realization of the Ergative clitic after sandhi processes have been applied. | ||

* The Stone Speaker dialect displays the greatest divergence from the other dialects phonologically, grammatically, and lexically. It was because of these differences that [[Minhast/Dialectology#The Tashunka Model| Dr. Tashunka]] has classified it as a separate | * The Stone Speaker dialect displays the greatest divergence from the other dialects phonologically, grammatically, and lexically. It was because of these differences that [[Minhast/Dialectology#The Tashunka Model| Dr. Tashunka]] has classified it as a separate language, which has become largely accepted among linguists today. | ||

== Phylogenic Models == | == Phylogenic Models == | ||

| Line 257: | Line 327: | ||

==== Criticisms ==== | ==== Criticisms ==== | ||

Academics criticize grouping the dialects under two branches as problematic. The most obvious problem is that of the Stone Speaker dialect, which not only has a large number of loans from Golahat and Peshpeg that far exceed those in the rest of the Lower Minhast dialects, but appears to be in the early stages of developing from a canonical SOV language into a non-configurational one. Arguments for classifying the Stone Speaker dialect as a separate language have been gaining momentum, the most vocal and convincing proponent being Dr. Napayshni Tashunka of the University of the Lakota Nation at Three Pipes. A new branch has been proposed for the Elk and Seal Speaker dialects, which realize ''-ūy'' with the voiced labio-velar approximant /w/, as in ''-ūwe'' and ''-ūwi'' respectively, in contrast with the voiced palatal consonant /j/ found in the rest of the Upper Minhast dialects. The Gull Speaker dialect presents its own problems. When the ''uyyi min kirim'' test is applied, the results are inconclusive: the dialect can be classified as a member of either the Upper or Lower Minhast branches, as both ''-we'' and ''-ia'' are found. | Academics criticize grouping the dialects under two branches as problematic. The most obvious problem is that of the Stone Speaker dialect, which not only has a large number of loans from Golahat and Peshpeg that far exceed those in the rest of the Lower Minhast dialects, but appears to be in the early stages of developing from a canonical SOV language into a non-configurational one. Arguments for classifying the Stone Speaker dialect as a separate language have been gaining momentum, the most vocal and convincing proponent being Dr. Napayshni Tashunka of the University of the Lakota Nation at Three Pipes. A new branch has been proposed for the Elk and Seal Speaker dialects, which realize ''-ūy'' with the voiced labio-velar approximant /w/, as in ''-ūwe'' and ''-ūwi'' respectively, in contrast with the voiced palatal consonant /j/ found in the rest of the Upper Minhast dialects. | ||

The Gull Speaker dialect presents its own problems, and they are several. When the ''uyyi min kirim'' test is applied, the results are inconclusive: the dialect can be classified as a member of either the Upper or Lower Minhast branches, as both ''-we'' and ''-ia'' are found. Along with the ''-we'' form, other features point towards a relationship with the Elk and Seal Speakers, which are grouped with the Upper Minhast dialects, yet the Gull Speakers do not share a contiguous border with them, so dialectal mixing has been ruled out at this point. The Palatization Test is also inconclusive, primarily due to dialect mixing with their Salmon Speaker and Dog Speaker neighbors, which belong to the northern dialects, and their Osprey Speaker and Egret Speaker neighbors, which belong to the southern dialects. Perhaps the most jarring feature of the Gull Speaker dialect is the placement of its verbal [[Minhast#Preverb_2_Locational_Affixes | deictic affixes]], which appear after the root in the Terminatives slot. Only the Salmonic and Horse Speaker dialects, as well as Classical Minhast, share this feature, whereas the rest of the Minhast dialects place the deictic affixes in the Preverb 2 slot. But using this feature to argue for an affiliation with Upper Minhast is problematic, as the forms of the Gull Speaker affixes are different from the aforementioned dialects. | |||

Additionally, the distinctive City Speaker dialect remains outside the Upper and Lower branch classification system. The language is a koine that developed from the Horse Speaker, Stone Speaker, and Gull Speaker dialects, with borrowings from Western sources. The dialect has also developed unique innovations of its own. This dialect thus provides yet another argument against the traditional two-branch dialectal division. | |||

<!-- | <!-- | ||

| Line 266: | Line 340: | ||

=== The Tashunka Model === | === The Tashunka Model === | ||

In his seminal work, ''Minhast: A Diachronic and Theoretical Study of a North Pacific Paleosiberian Language'', Dr. Tashunka remarked, "The traditional division of the Minhast dialects depicts a simple phylogeny. With the exception of the Salmonic dialects, which diverged from a common dialect after the Salmon Speaker-Horse Speaker War of 1473, no additional forks extend beyond each of the two main branches: each dialect within each branch is a sibling of each other. Nothing could be further from the truth. The current classification scheme does not account for the the discrepancies of the Gull Speaker data from that of the of the other Lower Minhast dialects with which it is grouped. The Horse Speaker data show that the dialect is much more conservative than has been previously thought, in some ways more so than the Salmonic dialects. Justification for placing the Elk and Seal Speaker dialects under the Upper Minhast branch lacks supporting data; although the Elk and Seal Speaker dialects are said to be more conservative than the dialects grouped under the traditional Lower Minhast dialects, the data indicate if anything that this characterization is at best overstated. Moreover, the evidence indicates that Classical Minhast, as it shares more in common with the dialects that have been traditionally classified as Upper Minhast, is not the ancestor of the Minhast dialects, but instead is an archaic dialect that diverged from one of the sub-branches of the northern dialects. Specifically, Classical Minhast shares more features with the Salmonic and Plateau dialects than with the other dialects; extreme conservatism by the Salmonic and Horse Speaker dialects cannot explain why they share these features with the classical language while all the other dialects do not exhibit at any point in time in their written history that they ever had these features. Only a close relationship, within a shared dialectal grouping, could account for these discrepencies. Rather than attempting to account for both the extinct and new dialects, the traditional classification scheme conveniently ignores them. Clearly, the evidence indicates a more complex picture of the Minhast dialects, but the current system is based on biased sources ultimately derived from both Minhast literary tradition and historical regional politics: twelve pre-eminent Speakers, thus twelve dialects." <ref>Dr. Tashunka also notes that Minhast numerology plays an important role: the number 12 is a fortuitous number, portending good fortune. </ref> To address these issues, Dr. Tashunka has proposed a new phylogenetic tree ''(dashes indicate conjectural relationships)'': | |||

In his seminal work, ''Minhast: A Diachronic and Theoretical Study of a North Pacific Paleosiberian Language'', Dr. Tashunka remarked, "The traditional division of the Minhast dialects depicts a simple phylogeny. With the exception of the Salmonic dialects, which diverged from a common dialect after the Salmon Speaker-Horse Speaker War of | |||

{{clade | {{clade | ||

| Line 299: | Line 371: | ||

|label1=''Plateau'' | |label1=''Plateau'' | ||

|1=Horse Speakers | |1=Horse Speakers | ||

|label2=''Salmonic'' < | |label2=''Salmonic'' <ref>We have an exact date when the Salmonic sub-branch split into the Salmon and Wolf Speaker dialects: The Salmon Speaker - Horse Speaker War of 1473</ref> | ||

|2={{clade | |2={{clade | ||

|1=Salmon Speakers | |1=Salmon Speakers | ||

| Line 306: | Line 378: | ||

}} | }} | ||

|3={{clade | |3={{clade | ||

|1=Classical Minhast < | |1=Classical Minhast <ref>Notice that Classical Minhast has moved from its basal position, as depicted in traditional phylogenies, to the Highland sub-branch of the Northern dialect branch. Old Minhast now occupies the basal position, making the tree consistent with the hypothesis that the Stone Speaker branch is a separate language.</ref> | ||

}} | }} | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 314: | Line 386: | ||

|3={{clade | |3={{clade | ||

|1 = {{clade | |1 = {{clade | ||

|1=Modern Standard Minhast < | |1=Modern Standard Minhast <ref>Modern Standard Minhast, although created as a "compromise" dialect with elements from both Upper and Lower Minhast dialects, nevertheless has a grammar that is mostly from Upper Minhast sources.</ref> | ||

}} | }} | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 361: | Line 433: | ||

}}<!-- Close Common--> | }}<!-- Close Common--> | ||

|label5='' | |label5=''Petric'' | ||

|5={{clade | |5={{clade | ||

|1=Stone Speaker < | |1=Stone Speaker <ref>Many Minhastic linguists, including Dr. Tashunka, argue that the Stone Speaker dialect should be reclassified as an independent language, based on how divergent it is from the other dialects. See discussion above.</ref> | ||

|2=Knife Speaker ''(extinct)'' <sup> ‡</sup> |state2=dashed | |2=Knife Speaker ''(extinct)'' <sup> ‡</sup> |state2=dashed | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 377: | Line 449: | ||

The reclassification of Classical Minhast has received especially scathing criticism from native Minhast grammarians and linguists. Dr. Tashunka proposed in another paper, "On the Position of Classical Minhast and the Modern Languages", that Classical Minhast was actually a prestige dialect spoken by another nomadic northern Minhast tribe, similar in lifestyle and social structure to today's modern Horse Speakers. He argues that this northern Minhast tribe, like the Horse Speakers, were extremely warlike and at one time may have united all of the Minhast groups under their rule, essentially forming a tribal empire. As a result, the speech of this northern tribe became a prestige dialect throughout all the Minhast groups. | The reclassification of Classical Minhast has received especially scathing criticism from native Minhast grammarians and linguists. Dr. Tashunka proposed in another paper, "On the Position of Classical Minhast and the Modern Languages", that Classical Minhast was actually a prestige dialect spoken by another nomadic northern Minhast tribe, similar in lifestyle and social structure to today's modern Horse Speakers. He argues that this northern Minhast tribe, like the Horse Speakers, were extremely warlike and at one time may have united all of the Minhast groups under their rule, essentially forming a tribal empire. As a result, the speech of this northern tribe became a prestige dialect throughout all the Minhast groups. | ||

There are two sources that suggest that a powerful tribe did gain political and military ascendancy in ancient Minhay. One is from the ''Anyaddaddaram'' (The Epic of Anyar), passed orally from generation to generation before finally being written down in Classical Minhast in the indigenous poetic genre known as the ''seksarambāt''. With close to 40,000 words, the epic tells of a young man named Anyar who fled the army of an invading empire and convinced all of the Minhast tribes to unite and drive away the invader. Anyar then gathers a large fleet and sets sail to attack the empire on its own soil. The poem abruptly ends, ''"Annūyikmammā tamaššuhapmakikman"'', "And they set sail in pursuit of the enemy". Another source comes from an outside nation, the Rajahnate of Kirmay. An anonymous court historian wrote ''Dagitoy a Sursurat ti Amianan a Pag'arian'' (The Book of the Northern Kingdom), widely regarded as an ancient treatise about the Empire of Yamato. However, various passages suggest that the kingdom in question was not Japan, as illustrated by the following passage: ''Dagiti kawes dagiti tatta'u dutdút a nalamúyut gapú ta ti ul'ulida nakalalam'ek, ket ti danúm nagbalbalin kasta ti batú. Ngem nu agawid idiay balbalayda, napudút ta isúda dutdút a nalamúyut met'', "The men wore fur because their homeland was cold, the water becoming hard as stone; but after returning home, their houses were warm, for they too were of fur"< | There are two sources that suggest that a powerful tribe did gain political and military ascendancy in ancient Minhay. One is from the ''Anyaddaddaram'' (The Epic of Anyar), passed orally from generation to generation before finally being written down in Classical Minhast in the indigenous poetic genre known as the ''seksarambāt''. With close to 40,000 words, the epic tells of a young man named Anyar who fled the army of an invading empire and convinced all of the Minhast tribes to unite and drive away the invader. Anyar then gathers a large fleet and sets sail to attack the empire on its own soil. The poem abruptly ends, ''"Annūyikmammā tamaššuhapmakikman"'', "And they set sail in pursuit of the enemy". Another source comes from an outside nation, the Rajahnate of Kirmay. An anonymous court historian wrote ''Dagitoy a Sursurat ti Amianan a Pag'arian'' (The Book of the Northern Kingdom), widely regarded as an ancient treatise about the Empire of Yamato. However, various passages suggest that the kingdom in question was not Japan, as illustrated by the following passage: ''Dagiti kawes dagiti tatta'u dutdút a nalamúyut gapú ta ti ul'ulida nakalalam'ek, ket ti danúm nagbalbalin kasta ti batú. Ngem nu agawid idiay balbalayda, napudút ta isúda dutdút a nalamúyut met'', "The men wore fur because their homeland was cold, the water becoming hard as stone; but after returning home, their houses were warm, for they too were of fur"<ref>Presumably the author is actually referring to animal hides with regards to the construction of the homes.</ref>. This passage is especially peculiar: unless the author was referring to Ainu enclaves in the island of Honshu in northern Japan, no native Japanese home is constructed out of animal hides or fur. Nevertheless, these suggestive passages in both the ''Anyaddaddaram'' and ''Dagitoy a Sursurat ti Amianan a Pag'arian'' are not sufficient to prove that a northern tribe speaking a dialect that would later become Classical Minhast conquered the other Minhast tribes and spread their dialect. | ||

<small><sup> ‡</sup>Dr. Tashunka notes, ''"Limited attestation hinders the classification of the Knife Speaker dialect. However, based on what texts we do have, we can determine which branches the Knife Speaker dialect does ''not'' belong to. The presence of Golahat words rules it out as a member of the Northern and Western Branches; the absence of ''-we-'' after application of the ''uyyi min kirim''-test rules it out as a member of the Gullic | == Footnotes == | ||

{{reflist}} | |||

<small><sup> ‡</sup>Dr. Tashunka notes, ''"Limited attestation hinders the classification of the Knife Speaker dialect. However, based on what texts we do have, we can determine which branches the Knife Speaker dialect does ''not'' belong to. The presence of Golahat words rules it out as a member of the Northern and Western Branches; the absence of ''-we-'' after application of the ''uyyi min kirim''-test rules it out as a member of the Gullic and Western branches. Dialectal mixing between the Heron Speakers and Stone Speakers is absent, but a few Stone Speaker words crop up in the Knife Speaker texts; this provides evidence that the Knife Speaker dialect should not be considered a member of the Insular Branch. This leaves only two other candidates, the Coastal and Petric groups, which the Knife Speaker dialect may grouped under, or it may even constitute a separate branch."'' </small> | |||

Latest revision as of 17:11, 7 June 2024

Introduction

The subject of Minhast dialectology has become the subject of heated debate, pitting native grammarians following traditional frameworks versus foreign linguists who have undertaken research that threatens older models. This article sets out to establish the context of this debate, describe the theoretical framework of the traditionalists, and research undertaken since the 1980's that challenges the traditionalist model.

Dialectal Divisions

Minhast is divided into fourteen dialects, twelve of which are the historical dialects spoken in the Prefectures, and two new dialects that have arisen in modern times, a standardized "national" dialect, and an urban colloquial dialect. Two additional dialects, the Knife Speaker dialect, and the Heron Speaker dialect1, are now extinct. The Knife Speaker dialect is poorly attested.

The dialects of the Prefectures have been traditionally grouped under two branches, Upper Minhast, and Lower Minhast. Within Upper Minhast, a further dialectal split emerged, leading to the Salmon Speaker and Wolf Speaker dialects. Minhast grammarians have traditionally classified the dialects according to the following phylogeny:

Upper Minhast, which consists of several dialects in the northern highlands, encompasses the Northern Coast, Northeastern Mountain Coastal Range (Gaššarat, lit. "basalt"), the Kilmay Rī Mountain Range, the Central Plateau (Kammak min Nukya), and the the Great Plains (Hamhāmarū , lit. "The Great Clearing of the Grasses"). Lower Minhast traditionally has been the branch containing the dialects south of the tribal territories (karak) of the Dog, Salmon and Horse Speakers. The uyyi min kirim, lit. "The (way) of saying the (sequence) -uyyi" is the primary test in determining which branch a given dialect should be grouped under, although other tests may be employed as well, such as the frequency of loanwords from the unrelated minority languages Peshpeg and Golahat, and a recently discovered, extinct non-Minhastic language called Corradi; the dialects of the Upper Minhast branch have virtually no loanwords from these languages, whereas the dialects of Lower Minhast branch have such loans in varying degrees. The Palatization Test is also used to classify dialects: the dialects from the Lower Minhast branch palatize /t/ and /d/ to [t͡ʃ] and [d͡ʒ] when followed by /j/, /ia͡/ or /ie͡/, a feature lacking in the dialects of the Upper Minhast branch.

"The Twelve Speakers" Classification System

| Branch | Dialect | Region/Prefecture/District | Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Minhast | Gāl min Kirmast "Horse Speaker" | Umbarak, Hayreb, Nanampuyyi, Wattare, Saxtam, Gannasia, Rummak , Iyyay, Hattūmi, Nu'ay, and Xirrim Prefectures; Āš-min-Gāl, Ankussūr, Huruk, Nammadīn, Kered, and Kattek (NW Quadrant of NCR, approx 60%) |

|

| Dūy min Kirmast "Salmon Speaker" | Hittaħm, Iskamharat, Tuhattam, Perim-Sin, Attum Attar, Yikkam min Akk, Ruyāya Prefectures; Iyyūmi (Salmon Speaker suburb in NCR, approx 80%) |

| |

| Hašlua min Kirmast "Wolf Speaker" | North Central, and Southern Kilmay Rī Mountains, Ešked, Tayyagur, Raqwar, Tabuk Prefectures; Ehar Township |

| |

| Kaslub min Kirmast "Dog Speaker" | Hisašarum, Way, Išpa, Warat, Tabbakun, Hara, Nassaškub, Neweyya, Uħpar, Nikwat, Salabūr, Tawāheb Prefectures; Bussum Demilitarized District |

| |

| Nurrappam Kirmast "Bear Speaker" | Tannumay, Puyya Prefectures |

| |

| Yattaxmin Kirmast "Fox Speaker" | Kardam, Eħħar, Yussuk Prefectures |

| |

| Naggikim Kirmast "Elk Speaker" | Meti, Attuar, Essak Prefectures |

| |

| Hurkadim Kirmast "Seal Speaker" | Pinda, Rukpu Prefectures |

| |

| Lower Minhast | Annea min Kirmast "Gull Speaker" | Kissamut, Tur'akkam, Senzil, Rēgum Prefectures; Bayburim, Talwasr/Talwāz, Uğabal (MSM: Urgabal), Tantanay, Nuwway, Kitamta, Antuwe, Sašlar (South Coast Colonies) |

|

| Neyūn min Kirmast "Osprey Speaker" | Uyyuš, Arinak, Naggiriyan, Nāz, Dayyat, Urria Prefectures |

| |

| Šunnekim Kirmast "Egret Speaker" | Nentie, Isku Prefectures |

| |

| Banakim Kirmast "Stone Speaker" | Sakkeb, Neskud,Yaxparim, Izgilbāš, Zurzugul, Higbilan, Narpaz Prefectures |

|

The Modern Dialects

Two new dialects have both arisen in the National Capital Region (NCR). Modern Standard Minhast, a conglomeration of the Upper Minhast and Lower Minhast dialects, as well as Classical Minhast, serves as the standard dialect used for government, commerce, and media. Despite that more than half of its lexicon is of Lower Minhast origin, the dialect is classified as part of the Upper Minhast branch due to its grammar, which is largely drawn from the Dog Speaker dialect. The National Academy of the Minhast Language serves as the official body in creating and maintaining the standardized form of the language and biannually publishes the Minhastim Kirim min Suharak (Dictionary of the Minhast Language). In spite of its official status, the adoption of Modern Standard Minhast by the Prefectures has been limited due to resistance from the local speech communities. The second dialect, known as the City Speaker dialect (aka Modern Colloquial Minhast), is an admixture of several dialects; although most of the lexicon comes from the dialects of the Common Branch, many Stone Speaker words from the Montaigne branch have been imported. Nevertheless the grammar is ultimately derived from the Common branch. The City Speaker dialect is centered in the official capital, Aškuan. This dialect contains more loanwords from foreign languages than the standard language, especially in areas of technology and the Internet, international sports, and from foreign films and media. The City Speaker dialect allows CCC consonant clusters in medial syllabic positions, while only final CC clusters are allowed. Initial CC clusters are also possible for a limited set of combinations, e.g. /kw/, /kr/, /kl/, /sm/, /sn/, /šm/,/šn/, /sl/, /šl/ . This new dialect is also replete with slang, loanwords (especially from Western sources) and nonstandard jargon that is often looked down upon by Speakers from the more conservative Prefectures.

Intelligibility

Mutual intelligibility between dialectal groups is affected by several factors. As a whole, the Upper Minhast group is regarded as more conservative in phonology and grammar compared to the Lower Minhast group, but even within each group there may be great differences in the lexicon arising oftentimes from differences in environment and lifestyle that may affect intelligibility. For example, the extremely conservative Salmon Speaker dialect has nevertheless developed a specialized vocabulary for terminology reflective of their riverine and coastal environment, while the Horse Speakers lack such terminology for the simple reason that their homeland is landlocked. Moreover, dialectal mixing is the norm, not the exception. The Gull Speakers, although grouped as a Lower Minhast dialect, can communicate with the Dog Speakers, who belong to the Upper Minhast branch, with little difficulty. This is because both Speakers share a common border and have long had extensive trade contacts with each other which have leveled lexical differences. The Osprey Speakers find the Stone Speakers virtually unintelligible even though both are grouped under the Lower Minhast branch; in fact Osprey Speakers report they can converse much more easily with the Wolf Speakers, an Upper Minhast dialect, despite the Wolf Speaker dialect's conservative features and affiliation with the Upper Minhast branch. The Osprey Speakers territories border Salmon Speaker Country; they too have had extensive trade relations with the Salmon Speakers and as a consequence both groups can understand each other despite belonging to two different branches. Bilingualism is common, and diglossia from usage of the prestige language, Classical Minhast, also complicates the linguistic landscape.

As an illustration of the dialectal differences, sample texts are provided below. They all mean, "Yes, (these are) the markings of my clan":

Modern Standard:

- Eyla, huzzakteškenkem baktemtakkemt.

eyla huzzakteš-kenk=de=min baktet-makkem=de

yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG=CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG

Salmon Speaker:

- Ēlā, huzzakteškenkide min baktemtakkemmide.

ēlā huzzakteš-kenk=de min baktet-makkem=de

yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG

Horse Speaker:

- Ħallā, ħuzzaktuškankada num baktumtakkammada.

ħallā ħuzzaktuš-kank=da min baktut-makkam=da

yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG

Dog Speaker:

- Eyla, huzzaktiškenkemin baktentakkent.

ēlā huzzaktiš-kenk=de=min baktet-makkem=de

yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG =ONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG

Osprey Speaker:

- Ayle, izzakiškenkim baktektemme.

able izzakš-kenk=e=min baktet-kemm=e

yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG=CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG

Gull Speaker:

- Ellay, uzzakteškenkin baktetunkemp.

ellay uzzakteš-kenk=de=min baktet-unkem=de

yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG=CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG

City Speaker:

- La', hizzakiškentim baktettakkent.

la' hizzakš-kenk=te=im baktet-nakken=te

yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG=CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG

Stone Speaker:

- Ia, zaguškunkun bekummunkuk.

ia zakš-kun=k=un bekut-munk=k

yes clan-3P.INAN+1S=ERG=CONN tattoo-3P.INAN+3P.COMM=ERG

- The ergative in the examples above also serves as a genitive marker, as in Yup'ik.

- The Upper Minhast (Salmon, Horse, and Dog Speaker) dialects, as can be seen in this text sample, show the greatest amount of conservatism, and all are mutually intelligible with each other, although the Dog Speaker dialect has diverged enough such that speakers of the other Upper Minhast dialects report difficulties in understanding it.

- Modern Standard Minhast (MSM) is closest, at least in morphology and syntax, to the Dog Speaker dialect[1]. However, monolingual Dog Speakers consider the national language difficult to understand, because over half of its lexicon is drawn from Lower Minhast sources, and some phonological rules which govern the allomorphs of certain affixes and clitics, such as the ergative =de, can differ significantly between the two dialects.

- For whatever reason, the Osprey speakers treat baktet "tattoo" as an animate noun. Intra-dialectal gender discordance is common.

- The Gull Speaker text shows some features found in the Upper Minhast text, and others in the Osprey Speaker text. Features in the Gull Speaker text not found in the other texts are the underlying form of the polypersonal agreement affix -unkem-, and the surface realization of the Ergative clitic after sandhi processes have been applied.

- The Stone Speaker dialect displays the greatest divergence from the other dialects phonologically, grammatically, and lexically. It was because of these differences that Dr. Tashunka has classified it as a separate language, which has become largely accepted among linguists today.

Phylogenic Models

Traditional Model

Traditional Phylogenetic Tree of the Minhast Dialects

| Classical Minhast |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Criticisms

Academics criticize grouping the dialects under two branches as problematic. The most obvious problem is that of the Stone Speaker dialect, which not only has a large number of loans from Golahat and Peshpeg that far exceed those in the rest of the Lower Minhast dialects, but appears to be in the early stages of developing from a canonical SOV language into a non-configurational one. Arguments for classifying the Stone Speaker dialect as a separate language have been gaining momentum, the most vocal and convincing proponent being Dr. Napayshni Tashunka of the University of the Lakota Nation at Three Pipes. A new branch has been proposed for the Elk and Seal Speaker dialects, which realize -ūy with the voiced labio-velar approximant /w/, as in -ūwe and -ūwi respectively, in contrast with the voiced palatal consonant /j/ found in the rest of the Upper Minhast dialects.

The Gull Speaker dialect presents its own problems, and they are several. When the uyyi min kirim test is applied, the results are inconclusive: the dialect can be classified as a member of either the Upper or Lower Minhast branches, as both -we and -ia are found. Along with the -we form, other features point towards a relationship with the Elk and Seal Speakers, which are grouped with the Upper Minhast dialects, yet the Gull Speakers do not share a contiguous border with them, so dialectal mixing has been ruled out at this point. The Palatization Test is also inconclusive, primarily due to dialect mixing with their Salmon Speaker and Dog Speaker neighbors, which belong to the northern dialects, and their Osprey Speaker and Egret Speaker neighbors, which belong to the southern dialects. Perhaps the most jarring feature of the Gull Speaker dialect is the placement of its verbal deictic affixes, which appear after the root in the Terminatives slot. Only the Salmonic and Horse Speaker dialects, as well as Classical Minhast, share this feature, whereas the rest of the Minhast dialects place the deictic affixes in the Preverb 2 slot. But using this feature to argue for an affiliation with Upper Minhast is problematic, as the forms of the Gull Speaker affixes are different from the aforementioned dialects.

Additionally, the distinctive City Speaker dialect remains outside the Upper and Lower branch classification system. The language is a koine that developed from the Horse Speaker, Stone Speaker, and Gull Speaker dialects, with borrowings from Western sources. The dialect has also developed unique innovations of its own. This dialect thus provides yet another argument against the traditional two-branch dialectal division.

The Tashunka Model

In his seminal work, Minhast: A Diachronic and Theoretical Study of a North Pacific Paleosiberian Language, Dr. Tashunka remarked, "The traditional division of the Minhast dialects depicts a simple phylogeny. With the exception of the Salmonic dialects, which diverged from a common dialect after the Salmon Speaker-Horse Speaker War of 1473, no additional forks extend beyond each of the two main branches: each dialect within each branch is a sibling of each other. Nothing could be further from the truth. The current classification scheme does not account for the the discrepancies of the Gull Speaker data from that of the of the other Lower Minhast dialects with which it is grouped. The Horse Speaker data show that the dialect is much more conservative than has been previously thought, in some ways more so than the Salmonic dialects. Justification for placing the Elk and Seal Speaker dialects under the Upper Minhast branch lacks supporting data; although the Elk and Seal Speaker dialects are said to be more conservative than the dialects grouped under the traditional Lower Minhast dialects, the data indicate if anything that this characterization is at best overstated. Moreover, the evidence indicates that Classical Minhast, as it shares more in common with the dialects that have been traditionally classified as Upper Minhast, is not the ancestor of the Minhast dialects, but instead is an archaic dialect that diverged from one of the sub-branches of the northern dialects. Specifically, Classical Minhast shares more features with the Salmonic and Plateau dialects than with the other dialects; extreme conservatism by the Salmonic and Horse Speaker dialects cannot explain why they share these features with the classical language while all the other dialects do not exhibit at any point in time in their written history that they ever had these features. Only a close relationship, within a shared dialectal grouping, could account for these discrepencies. Rather than attempting to account for both the extinct and new dialects, the traditional classification scheme conveniently ignores them. Clearly, the evidence indicates a more complex picture of the Minhast dialects, but the current system is based on biased sources ultimately derived from both Minhast literary tradition and historical regional politics: twelve pre-eminent Speakers, thus twelve dialects." [2] To address these issues, Dr. Tashunka has proposed a new phylogenetic tree (dashes indicate conjectural relationships):

| Old Minhast |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The reclassification of Classical Minhast has received especially scathing criticism from native Minhast grammarians and linguists. Dr. Tashunka proposed in another paper, "On the Position of Classical Minhast and the Modern Languages", that Classical Minhast was actually a prestige dialect spoken by another nomadic northern Minhast tribe, similar in lifestyle and social structure to today's modern Horse Speakers. He argues that this northern Minhast tribe, like the Horse Speakers, were extremely warlike and at one time may have united all of the Minhast groups under their rule, essentially forming a tribal empire. As a result, the speech of this northern tribe became a prestige dialect throughout all the Minhast groups.

There are two sources that suggest that a powerful tribe did gain political and military ascendancy in ancient Minhay. One is from the Anyaddaddaram (The Epic of Anyar), passed orally from generation to generation before finally being written down in Classical Minhast in the indigenous poetic genre known as the seksarambāt. With close to 40,000 words, the epic tells of a young man named Anyar who fled the army of an invading empire and convinced all of the Minhast tribes to unite and drive away the invader. Anyar then gathers a large fleet and sets sail to attack the empire on its own soil. The poem abruptly ends, "Annūyikmammā tamaššuhapmakikman", "And they set sail in pursuit of the enemy". Another source comes from an outside nation, the Rajahnate of Kirmay. An anonymous court historian wrote Dagitoy a Sursurat ti Amianan a Pag'arian (The Book of the Northern Kingdom), widely regarded as an ancient treatise about the Empire of Yamato. However, various passages suggest that the kingdom in question was not Japan, as illustrated by the following passage: Dagiti kawes dagiti tatta'u dutdút a nalamúyut gapú ta ti ul'ulida nakalalam'ek, ket ti danúm nagbalbalin kasta ti batú. Ngem nu agawid idiay balbalayda, napudút ta isúda dutdút a nalamúyut met, "The men wore fur because their homeland was cold, the water becoming hard as stone; but after returning home, their houses were warm, for they too were of fur"[7]. This passage is especially peculiar: unless the author was referring to Ainu enclaves in the island of Honshu in northern Japan, no native Japanese home is constructed out of animal hides or fur. Nevertheless, these suggestive passages in both the Anyaddaddaram and Dagitoy a Sursurat ti Amianan a Pag'arian are not sufficient to prove that a northern tribe speaking a dialect that would later become Classical Minhast conquered the other Minhast tribes and spread their dialect.

Footnotes

- ^ More specifically, the variety as spoken in Tagna Prefecture, as can be seen from the -m- → -n- morphophonemic alternation when the pronominal affix combines with the ergative/genitive clitic, which differs from most Dog Speaker dialects.

- ^ Dr. Tashunka also notes that Minhast numerology plays an important role: the number 12 is a fortuitous number, portending good fortune.

- ^ We have an exact date when the Salmonic sub-branch split into the Salmon and Wolf Speaker dialects: The Salmon Speaker - Horse Speaker War of 1473

- ^ Notice that Classical Minhast has moved from its basal position, as depicted in traditional phylogenies, to the Highland sub-branch of the Northern dialect branch. Old Minhast now occupies the basal position, making the tree consistent with the hypothesis that the Stone Speaker branch is a separate language.

- ^ Modern Standard Minhast, although created as a "compromise" dialect with elements from both Upper and Lower Minhast dialects, nevertheless has a grammar that is mostly from Upper Minhast sources.

- ^ Many Minhastic linguists, including Dr. Tashunka, argue that the Stone Speaker dialect should be reclassified as an independent language, based on how divergent it is from the other dialects. See discussion above.

- ^ Presumably the author is actually referring to animal hides with regards to the construction of the homes.

‡Dr. Tashunka notes, "Limited attestation hinders the classification of the Knife Speaker dialect. However, based on what texts we do have, we can determine which branches the Knife Speaker dialect does not belong to. The presence of Golahat words rules it out as a member of the Northern and Western Branches; the absence of -we- after application of the uyyi min kirim-test rules it out as a member of the Gullic and Western branches. Dialectal mixing between the Heron Speakers and Stone Speakers is absent, but a few Stone Speaker words crop up in the Knife Speaker texts; this provides evidence that the Knife Speaker dialect should not be considered a member of the Insular Branch. This leaves only two other candidates, the Coastal and Petric groups, which the Knife Speaker dialect may grouped under, or it may even constitute a separate branch."