Aryan: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (216 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

{{Construction}} | {{Construction}} | ||

'''Aryan''' (''* | '''Aryan''' (''*Ai̯ri̯áh<sub>0</sub>'', [[w:Help:IPA|[əi̯ˈri̯əʔ]]]), also referred to as '''Pre-Proto-Indo-European,''' is an [[ab interiori language]] depicting the transition from [[Paleolithic Codes]] to [[w:Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European]] (PIE). There are no historical records of its existence, or comparative data to support it; rather, it is an abductive experiment based on the hypothesis of [[Transitional Dialects]]. | ||

In most of known [[w:History|History]], indo-european speaking populations have been widespread in [[w:Eurasia|Eurasia]], bearing fruits from civilizations such as those of the [[w:Roman empire|Roman Empire]], the [[w:Ancient Greece|Hellenistic City-States]], and the [[w:List of ancient Indo-Aryan peoples and tribes|Rigvedic Tribes]]. Memorable personalities who spoke natively dialects from those areas include the roman general [[w:Gaius Julius Caesar|Julius Caesar]] (speaker of [[w:Latin|Latin]]), the macedonian king [[w:Alexander the Great|Alexander the Great]] (speaker of [[w:Ancient Greek|Ancient Greek]]), the nazi chancellor [[w:Adolf Hitler|Adolf Hitler]] (speaker of [[w:German language|German]]), the french emperor [[w:Napoleon Bonaparte|Napoleon Bonaparte]] (speaker of [[w:Corsican langugae|Corsican]]), the british physicist [[w:Isaac Newton|Isaac Newton]] (speaker of [[w:English language|English]]), the italian renascentist [[w: | In most of known [[w:History|History]], indo-european speaking populations have been widespread in [[w:Eurasia|Eurasia]], bearing fruits from civilizations such as those of the [[w:Roman empire|Roman Empire]], the [[w:Ancient Greece|Hellenistic City-States]], and the [[w:List of ancient Indo-Aryan peoples and tribes|Rigvedic Tribes]]. Memorable personalities who spoke natively dialects from those areas include the roman general [[w:Gaius Julius Caesar|Julius Caesar]] (speaker of [[w:Latin|Latin]]), the macedonian king [[w:Alexander the Great|Alexander the Great]] (speaker of [[w:Ancient Greek|Ancient Greek]]), the nazi chancellor [[w:Adolf Hitler|Adolf Hitler]] (speaker of [[w:German language|German]]), the french emperor [[w:Napoleon Bonaparte|Napoleon Bonaparte]] (speaker of [[w:Corsican langugae|Corsican]]), the british physicist [[w:Isaac Newton|Isaac Newton]] (speaker of [[w:English language|English]]), the italian renascentist [[w:Leonardo da Vinci|Leoanardo da Vinci]] (speaker of [[w:Tuscan dialect|Tuscan Italian]]), the indian ascetic [[w:Gautama Buddha|Gautama Buddha]] (speaker of [[w:Prakrit language|Prakrit]]), et cetera. Also, due the trajectory of the linguistic stock along the millenia, some of the most culturally influential works of Literature have been yielded, such as the [[w:Vulgate|Vulgate]], the [[w:Iliad|Iliad]], and the [[w:Vedas|Vedas]]. As of the [[w:21st Century|21<sup>st</sup> Century]], half of the world's population speaks 454 indo-european languages<ref>https://www.ethnologue.com/</ref>, with the [[w:Americas|Americas]], [[w:Europe|Europe]], [[w:Iran|Iran]], [[w:Pakistan|Pakistan]], and [[w:India|India]] being today the centers of native speakers due the [[w:Indo-European migrations|Indo-European Migrations]] and [[w:Colonial empires|European Colonialism]]. | ||

Naturally, the origin of the [[w:Indo-European languages|indo-european family]] has attracted the curiosity of thousands of researchers in the last centuries, since [[w:William Jones (philologist)|William Jones']] presidential discourse to the Asiatic Society in 1786<ref>https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sanskrit-language</ref>, which famously addressed the similarity between [[w:Sanskrit|Sanskrit]] and [[w:Languages of Europe|european languages]]. '''Further works that [...]''' | Naturally, the origin of the [[w:Indo-European languages|indo-european family]] has attracted the curiosity of thousands of researchers in the last centuries, since [[w:William Jones (philologist)|William Jones']] presidential discourse to the Asiatic Society in 1786<ref>https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sanskrit-language</ref>, which famously addressed the similarity between [[w:Sanskrit|Sanskrit]] and [[w:Languages of Europe|european languages]]. '''Further works that [...]''' | ||

In the hybrid model, Aryan must have been spoken somewhere near the Caucasus Mountains in compliance with the [[w:Armenian hypothesis|Armenian Hypothesis]], which in its current form holds that the speakers of "Pre-Proto-Indo-European" pertained to the genepool of the [[w:Caucasus hunter-gatherer|Caucasian Hunter-Gatherers]] (CHG)<ref name= | In the hybrid model, Aryan must have been spoken somewhere near the Caucasus Mountains in compliance with the [[w:Armenian hypothesis|Armenian Hypothesis]], which in its current form holds that the speakers of "Pre-Proto-Indo-European" pertained to the genepool of the [[w:Caucasus hunter-gatherer|Caucasian Hunter-Gatherers]] (CHG)<ref name=Lazaridis>Lazaridis et alii (2022); ''The genetic history of the Southern Arc: a bridge between West Asia and Europe''</ref>, who would eventually contribute to the formation of the [[w:Yamnaya culture|Yamnaya Culture]] and the dispersion of "Core Proto-Indo-European" as detailed in the [[w:Kurgan hypothesis|Kurgan Hypothesis]]. The age of the language is more controversial, being set between 12,000 and 10,000 years Before Present (BP), or the double of its daughter-language's, to coincide with the notion of [[Linguistic Modernity]]. | ||

==Etymology== | |||

The word ''*Ai̯ri̯áh<sub>0</sub>'' is influenced but not based on the Indo-Iranian ethnonym ''*Áryas'' "Aryan", as the root ''*h<sub>5</sub>ir'' "member/comrade" comes from Pangaean ''ʕihr'' "racial person". | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

===Development from Paleolithic Codes=== | ===Development from Paleolithic Codes=== | ||

The | The story of Aryan starts with the transition from Atomism to Double Articulation, or from the [[Pangaean Code]] to Neolithic dialects (circa 12,000 BP). Noticeable is the influence of the [[Diluvian Code|Diluvian]] and [[Hyperborean Code|Hyperborean]] Codes, which triggered several sound changes: | ||

*Weak (plosive) stops become aspirated/murmured preceding a laryngeal consonant, as strong (ejective/implosive) stops gain plosive qualities in the same position.<br> | *Weak (plosive) stops become aspirated/murmured preceding a laryngeal consonant, as strong (ejective/implosive) stops gain plosive qualities in the same position.<br> | ||

| Line 324: | Line 327: | ||

|''*wid-rás'' "aquatic" | |''*wid-rás'' "aquatic" | ||

|''*ud-rós'' "aquatic" | |''*ud-rós'' "aquatic" | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''ˈkhuħ-ə'' "sound" | |''ˈkhuħ-ə'' "sound" | ||

| Line 342: | Line 337: | ||

|} | |} | ||

===Development into Indo-European Languages=== | ===Development into Indo-European Languages [...]=== | ||

Some tendences include the aspirated velars of Aryan becoming the PIE palatal series (*Kʰ ⇒ *Ḱ); .... | |||

https://en.wiktionary.org/w/index.php?title=Category:Proto-Indo-European_roots&from=A | |||

{| class="wikitable" | *bʰeyh₂- | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | |||

!Codex | !Codex | ||

!Aryan | !Aryan | ||

| Line 354: | Line 352: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| k̠- | | k̠- | ||

| | | *kʰpʰ- | ||

| | | *ǵʰ-d | ||

| | | 1. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/ǵʰewd-|''*ǵʰewd-'']] "to pour", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/ǵʰed-|''*ǵʰed-'']] "to defecate", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/ḱh₂d-|''*ḱh₂d-'']] "to fall" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -k̠ | | -k̠ | ||

| | | *-kp | ||

| | | *-k<sup>w</sup> | ||

| | | 1. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/leykʷ-|''*leykʷ-'']] "to leave" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| k- | | k- | ||

| *kʰ- | | *kʰ- | ||

| *ḱ | | *ḱ | ||

| ''* | | 1. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/ḱe|''*ḱe'']] "this" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -k | | -k | ||

| Line 375: | Line 373: | ||

| k̟- | | k̟- | ||

| *kʰtʰ- | | *kʰtʰ- | ||

| *ḱ | | *ḱ-s | ||

| | | 1. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/(s)ker-|''*(s)ker-'']], [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/(s)kelH-|''*(s)kelH'']], [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/sek-|''*sek-'']], [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/ḱes-|''*ḱes-'']], [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/kh₂eyd-|''*kh₂eyd-'']] "to cut"; 3. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/gleyH-|''*gleyH-'']] "to stick", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰreyH-|''*bʰreyH-'']] "to cut" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -k̟ | | -k̟ | ||

| | | *-kt | ||

| | | *p-ḱ | ||

| | | 1. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/peh₂ḱ-|''*peh₂ḱ-'']] "to join", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/peh₂ǵ-|''*peh₂ǵ-'']] "to attach"; 2. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/leyp-|''*leyp-'']] "to stick", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/leyǵ-|''*leyǵ-'']] "to bind"; 3. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰendʰ-|''*bʰendʰ-'']] "to bind", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/deh₁-|''*deh₁-'']] "to bind" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| g̠- | | g̠- | ||

| *gʰbʰ- | | *gʰbʰ- | ||

| *gʰ | | *gʰ-bʰ | ||

| | | 1. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/(s)pregʰ-|''*(s)pregʰ-'']] "sprinkle", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/glewbʰ-|''*glewbʰ-'']] "split", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰeh₂g-|''*bʰeh₂g-'']] "to divide"; 3. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰeyd-|''*bʰeyd-'']] "to split", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/deh₂-|''*deh₂-'']] "to divide" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -g̠ | | -g̠ | ||

| -gb | |||

| | | | ||

| | | *h₁éǵʰ "out" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| g- | | g- | ||

| Line 405: | Line 403: | ||

| g̟- | | g̟- | ||

| *gʰdʰ- | | *gʰdʰ- | ||

| *gʰ | | *gʰ-dʰ | ||

| '' | | [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/gʰedʰ-|''*gʰedʰ-'']] "to join", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰendʰ-|''*bʰendʰ-'']] "to bind" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -g̟ | | -g̟ | ||

| *-gd | | *-gd | ||

| *ǵ/∅ | | *ǵ/∅ | ||

| ''ʕihg̟'' | | ''ʕihg̟'' ⇒ ''*h<sub>5</sub>igd-'' ⇒ ''*leǵ-'' "to gather" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| k̠ʼ- | | k̠ʼ- | ||

| *kp- | | *kp- | ||

| *g | | *bʰ-g, *k-p | ||

| | | [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰeg-|''*bʰeg-'']] "break", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰreg-|''*bʰreg-'']] "break", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰrew-|''*bʰrew-'']] "break", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰrews-|''*bʰrews-'']] "break", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/kelh₂-|''*kelh₂-'']] "break", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/(s)kep-|''*(s)kep-'']] "break", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/Hrewp-|''*Hrewp-'']] "break" [may be from [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/Hrew-|''*Hrew-'']] "tear out"] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -k̠ʼ | | -k̠ʼ | ||

| *-kʰpʰ | | *-kʰpʰ | ||

| *ǵ | | *w-ǵ | ||

| | | ''*lewǵ-'' ~ ''*weh₂ǵ-'' ~ ''*wreh₁ǵ-'' "to break" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| kʼ- | | kʼ- | ||

| Line 440: | Line 438: | ||

| -k̟ʼ | | -k̟ʼ | ||

| -kʰtʰ | | -kʰtʰ | ||

| * | | *ǵʰ/dʰ ~ *∅/dʰ | ||

| ''ʕihk̟ʼ'' | | ''ʕihk̟ʼ'' ⇒ ''*h<sub>5</sub>ikʰtʰ-'' ⇒ ''*dʰerǵʰ-'' "to be firm" ~ ''*dʰer-'' "to support" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| ɠ̠- | | ɠ̠- | ||

| *gb- | | *gb- | ||

| *kʷ ~ *(s)k | | *kʷ ~ *(s)k | ||

| ''ɠ̠ʕih'' | | ''ɠ̠ʕih'' ⇒ ''*gbih<sub>1</sub>-'' ⇒ ''*kʷelh<sub>1</sub>-'' "to turn around"; ''ɠ̠ʕihr'' ⇒ ''*gbair-'' > ''*(s)ker-'' "to bend" [semantic transition from "shrink/wither" to "bend/turn around"] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -ɠ̠ | | -ɠ̠ | ||

| Line 466: | Line 464: | ||

| *gd- | | *gd- | ||

| *gʰ/∅ ~ *ḱ/∅ | | *gʰ/∅ ~ *ḱ/∅ | ||

| ''ɠ̟ʕih'' | | ''ɠ̟ʕih'' ⇒ ''*gdih<sub>1</sub>-'' ⇒ ''*gʰreh<sub>1</sub>-'' "to grow (plants)"; ''ɠ̟ʕihr'' ⇒ ''*gdair-'' ⇒ *ḱer- "to grow" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -ɠ̟ | | -ɠ̟ | ||

| *-gʰdʰ | | *-gʰdʰ | ||

| *gʰ/dʰ | | *gʰ/dʰ | ||

| ''hohɠ̟'' "growing fire" | | ''hohɠ̟'' "growing fire" ⇒ ''*hogʰdʰ-'' ⇒ ''*dʰegʷʰ-'' "to burn" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| p̠- | | p̠- | ||

| | | *pʰtʰ- | ||

| | | *bʰ/gʷ | ||

| | | [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰegʷ-|''*bʰegʷ-'']] "flee", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰewg-|''*bʰewg-'']] "flee" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -p̠ | | -p̠ | ||

| Line 484: | Line 482: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| p- | | p- | ||

| *pʰ | | *pʰ- | ||

| *bʰ | | *bʰ- | ||

| | | [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰer-|''*bʰer-'']] "bear" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -p | | -p | ||

| Line 495: | Line 493: | ||

| p̟- | | p̟- | ||

| *pʰkʰ- | | *pʰkʰ- | ||

| *bʰ/gʰ ~ *p/k | | *bʰ/gʰ ~ *p/ḱ ~ *p/k | ||

| ''p̟ʕih'' | | ''p̟ʕih'' ⇒ ''*pʰkʰih<sub>1</sub>-'' ⇒ ''*gʰabʰ-'' ~ ''*gʰeh₁bʰ-'' ~ ''*kap-'' "to seize", ''*peḱ-'' "to pluck" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -p̟ | | -p̟ | ||

| Line 536: | Line 534: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| p̠ʼ- | | p̠ʼ- | ||

| *pt- | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -p̠ʼ | | -p̠ʼ | ||

| | | *-pʰtʰ | ||

| | | *bʰ-dʰ | ||

| | | [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰedʰ-|''*bʰedʰ-'']] "dig" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| pʼ- | | pʼ- | ||

| | | *p- | ||

| | | *p | ||

| | | [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/per-|''*per-'']] "go through", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/pel-|''*pel-'']] "drive", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/pent-|''*pent-'']] "pass", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/pes-|''*pes-'']] "penis" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -pʼ | | -pʼ | ||

| | | *-pʰ | ||

| | | *bʰ | ||

| | | [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰerH-|''*bʰerH-'']] "pierce" | ||

|- | |- | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 588: | Line 586: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| ɓ̟- | | ɓ̟- | ||

| | | *bʰ- | ||

| | | *bʰ | ||

| | | [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰed-|''*bʰed-'']] "improve" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| -ɓ̟ | | -ɓ̟ | ||

| Line 718: | Line 716: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | |- | ||

| ʘ̠- | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

: * | |- | ||

| -ʘ̠ | |||

: * | | | ||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| ʘ- | |||

| *dʷ- | |||

| *bʰ- | |||

| [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰed-|''*bʰed-'']] "improve", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰil-|''*bʰil-'']] "lovely" | |||

|- | |||

r | | -ʘ | ||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| ʘ̟- | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| -ʘ̟ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| ǀ̠- | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| -ǀ̠ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| ǀ- | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| -ǀ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰeyh₂-|''*bʰeyh₂-'']] "to shake" | |||

|- | |||

| ǀ̟- | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| -ǀ̟ | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| r- | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| 3. [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰuH-|''*bʰuH-'']] "to be" | |||

|- | |||

| -r | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|} | |||

[[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰerǵʰ-|''*bʰerǵʰ-'']] "ascend" | |||

: *bʰegʷ- "to flee" < *-pʰtʰ "to escape" < … | |||

: *bʰeyd ~ *delh<sub>1</sub> “to split” | : *bʰerǵʰ- "to rise up " < *pk- "to eject" (?) | ||

: *bʰil "good" < *dʷih<sub>1</sub> | |||

[[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/ǵʰes-|''*ǵʰes-'']] "hand", [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/ǵʰey-|''*ǵʰey-'']] "winter" (earlier lexical transition from "autumn", with similar use of English "fall"), | |||

[[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/gʷʰer-|''*gʷʰer-'']] "warm" [from ''*gʰbʰōr-'' "glow"], [[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/bʰeh₃g-|''*bʰeh₃g-'']] "bake/roast" [from ''*gʰbʰor-'' "kindle"] | |||

*temh<sub>1</sub> | |||

kpih1 > bʰeg-; h5ikʰpʰ > weh2ǵ- ∅ | |||

r is added when the laryngeal is modified (h2 > h1) | |||

l is added when the laryngeal is erased (h1 > ∅) | |||

∅ (H) > r (H̥) > l (∅) | |||

*bʰewdʰ “to be awake” | |||

: *bʰeyd ~ *delh<sub>1</sub> “to split” | |||

: *deh<sub>2</sub>y- ~ *bʰeh<sub>2</sub>g- "to divide" | : *deh<sub>2</sub>y- ~ *bʰeh<sub>2</sub>g- "to divide" | ||

| Line 2,493: | Line 2,564: | ||

==Historical and Geographical Distribution== | ==Historical and Geographical Distribution== | ||

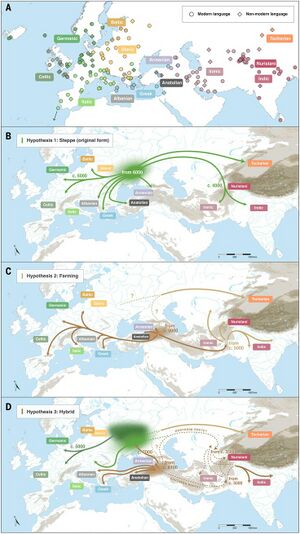

Since Lazaridis et al's paper<ref name= | Since Lazaridis et al's paper<ref name=Lazaridis>Lazaridis et alii (2022); ''The genetic history of the Southern Arc: a bridge between West Asia and Europe''</ref>, absence of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern%20hunter-gatherer Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer] (EHG) ancestry in the Anatolian component of the Indo-European speaking populations has suggested a caucasian homeleand for earlier stages of PIE rather than a pre-Yamnaya pontic continuance. Recent studies<ref>Brami (2019), ''Anatolia: from the origins of agriculture to the spread of Neolithic economies''</ref><ref>Ulas et al (2024), ''Drawing diffusion patterns of Neolithic agriculture in Anatolia''</ref>, furthermore, point to a total farming economy by the Zagros around 6,000 BC, which tempts an older dating for a Transitional Dialect such as Aryan. | ||

==Phonology== | ==Phonology== | ||

| Line 2,655: | Line 2,726: | ||

| | | | ||

|} | |} | ||

*The most promiment feature of the Aryan inventory is the presence of laryngeals [...] it possessess 7 in total: <''*h''><sub>0</sub> /ʔ/, <''*h''><sub>1</sub> /h/, <''*h''><sub>2</sub> /ħ/, <''*h''><sub>3</sub> /x/, <''*h''><sub>4</sub> /ɦ/, <''*h''><sub>5</sub> /ʕ/, <''*h''><sub>6</sub> /ɣ/ | |||

===Vowels=== | ===Vowels=== | ||

| Line 2,739: | Line 2,812: | ||

===Pitch Accent=== | ===Pitch Accent=== | ||

==Morphology== | ==Morphology== [...] | ||

[...] | |||

DILUVIAN PARTICLES ... -n (gen), -pʰa (dat) | |||

When inflected, lemmas become obliques (weakened). | |||

masc/fem | neut in adjectives | |||

fem masc/neut in verbs | |||

words for colors are easily derivatives due their expressivity | |||

roots not allowed: **deb, **tebʰ | |||

*h2 was not originally a collective particle ... | |||

*su (generic third-person) > *swé (generic reflexive | |||

-em/-ens adjectives ... mostly animate/inanimate distinction with masculine/feminine inflection relegated to pronouns | |||

comparative *yes, superlative *isto | |||

===Affix=== | ===Affix=== | ||

| Line 2,747: | Line 2,835: | ||

*gʷaināsay, *gʷaināmas | *gʷaināsay, *gʷaināmas | ||

Aryan | Aryan morphology deals with full-grade (_) and null-grade (∅). | ||

Aryan ''*(á)-s'' [PIE ''*(ó)-s''] forms nouns, as in ''*p<sup>h</sup>árs'' "thief" [PIE ''*b<sup>h</sup>ṓr'' "thief"] from ''*p<sup>h</sup>air'' "bearing". | |||

Aryan ''*(_)-as'' [PIE ''*(é)-os''] forms active animate nouns, as in ''kʰúh<sub>2</sub>as'' "living sound" [PIE ''*ḱlewos'' "fame"]. If the meaning intended is "racial", furthermore, the affix becomes ''*(_)-(a)ras'' [PIE ''*(∅)-(u)ros''], as in ''h<sub>5</sub>ímsaras'' "engenderer" [PIE ''*h<sub>2</sub>ḿ̥suros'' "deity"]. | |||

Aryan ''*(∅)-ás'' [PIE ''*(e)-ós''] forms active animate adjectives, as in ... | |||

Aryan ''*(á)-as'' [PIE ''*(ó)-os''] forms passive animate nouns, as in ''*p<sup>h</sup>áras'' "what is born" [PIE ''*b<sup>h</sup>óros'' "what is brought"] | |||

Aryan ''*(a)-ás'' [PIE ''*(o)-ós''] forms passive animate adjectives, as in ... became agentive instead of passive in PIE, but some archaic forms remain, such as *gʰoysós "spear" | |||

Aryan ''*(_)-ar'' [PIE *([é/ó)-r̥] forms active inanimate nouns, as in ''*húdar'' "water" [PIE ''*wódr̥'' "water"] | |||

Aryan ''*(∅)-ár'' forms active inanimate adjectives. | |||

*(_)-tár | Aryan ''*(á)-ar'' forms passive inanimate nouns. | ||

*(_)-tram | |||

Aryan ''*(a)-ár'' forms passive inanimate adjectives. | |||

- | |||

Aryan ''*(_)-tár'' forms agent nouns. | |||

Aryan ''*(_)-tram'' forms instrument nouns. It is a fusion of ''*(_)-tár'' [agent particle] and ''*-am'' [neuter particle] | |||

Aryan ''*(∅)-C-ás'' [PIE ''*(∅)-mós''] [forms derived nouns through mobile roots] EX: ''*pʰtʰūymás'' PIE = | |||

===Root=== | ===Root=== | ||

| Line 2,777: | Line 2,876: | ||

===Ablaut=== | ===Ablaut=== | ||

===Case=== | |||

Aryan possesses 5 primary cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, locative, and dative), with '''X''' secondary cases seen as borrowed affixes. [...] In PIE, the secondary forms of the genitive and dative became canonic in some pronouns and noun declensions, as the development of "mine" and "to you" show: | |||

: | : ''*aiǵṓn'', ''*nn'' (Aryan) ⇒ ''*h<sub>1</sub>eǵóm'', ''*méne'' (PIE) ⇒ ''अहम्'', ''मम'' (Sanskrit) | ||

: ''*tū́'', ''*tu̯pʰa'' (Aryan) ⇒ ''*tuH'', ''*tébʰi'' (PIE) ⇒ ''tu'', ''tibi'' (Latin) | |||

[...] | |||

The Indo-european accusative ''*-m'' ... as an earlier allative<ref name=Pooth>Pooth et alii (2018); [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324360155%20The%20Origin%20of%20Non-Canonical%20Case%20Marking%20of%20Subjects%20in%20Proto-Indo-European%20Accusative%20Ergative%20or%20Semantic%20Alignment The Origin of Non-Canonical Case Marking of Subjects in Proto-Indo-European: Accusative, Ergative, or Semantic Alignment]</ref> | |||

While | |||

: ''*h<sub>1</sub>i-m'' 3.SG-ACC (PIE) ⇒ ''μίν'' 3.SG.MASC.ACC (Greek) | |||

: | : ''*h<sub>1</sub>i-s'' 3.SG-NOM (PIE) ⇒ ''is'' 3.SG.MASC.NOM (Latin) | ||

===Noun=== | |||

< | |||

*h0e * eah0 *as *ats | [...] | ||

**pʰirás > pʰā́r = *dʰgʰūmás > *gʰā́mar, *gʰā́man | |||

**pʰerós > *phṓr dʰ | |||

aes, eah<sub>0</sub>, ad, sa [animated distal], tad [inanimated distal], aestad, eātad, atad | ===Fossilization of object affix into the anaphoric pronoun ''*i''=== | ||

{{interlinear|lang=fi|number=(1) | |||

|top= '''dieser''' Mensch | |||

|ˈdiːzɐ ˈMɛnʃ | |||

|diːz-ɐ Mɛnʃ-∅ | |||

|{{gcl|DEI}}.{{gcl|PRX}}-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} person-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} | |||

|"this person" (German) | |||

}} | |||

{{interlinear|lang=fi|number=(2) | |||

|top= '''этот''' человек | |||

|ˈɛtət t͡ɕɪɫɐˈvʲek | |||

|ɛt-ət t͡ɕɪɫɐvʲek-∅ | |||

|{{gcl|DEI}}-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} person-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} | |||

|"this person" (Russian) | |||

}} | |||

{{interlinear|lang=fi|number=(3) | |||

|top= '''iste''' homo | |||

|ˈiste ˈhomoː | |||

|ist-e hom-oː | |||

|{{gcl|DEI}}.{{gcl|PRX}}-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} person-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} | |||

|"this person" (Latin) | |||

}} | |||

{{interlinear|lang=fi|number=(4) | |||

|top= '''οὗτος''' ἄνθρωπος | |||

|ˈhûːtos ˈántʰrɔːpos | |||

|hûːt-os ántʰrɔːp-os | |||

|{{gcl|DEI}}.{{gcl|PRX}}-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} person-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} | |||

|"this person" (Greek) | |||

}} | |||

{{interlinear|lang=fi|number=(5) | |||

|top= '''सः''' मनुष्यः | |||

|sɐ́h mɐnuʂíjɐh | |||

|sɐ́-h mɐnuʂíj-ɐh | |||

|{{gcl|3}}-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} person-{{gcl|MASC}}.{{gcl|SG}}.{{gcl|NOM}} | |||

|"this person" (Sanskrit) | |||

}} | |||

The [...] | |||

As the cases of pronominal determiners found in the daughter languages are innovations, anaphoric demonstratives supposedly acted exclusively as pronouns in PIE, merely substituting the nouns as in Latin ''is, ea, id''; so that the sense of "this person" was represented by "the person here": | |||

{{interlinear|lang=fi|number=(1) | |||

|top= *[X]-*ḱe | |||

|*[X]-*ḱe | |||

|person.-{{gcl|DEI}}.{{gcl|PROX}} | |||

|"this person" (PIE) | |||

}} | |||

{{interlinear|lang=fi|number=(2) | |||

|top= *[X] *ikʰ | |||

|*[X] *i-*kʰ | |||

|person {{gcl|3}}-{{gcl|DEI}}.{{gcl|PROX}} | |||

|"this person" (Aryan) | |||

}} | |||

{{interlinear|lang=fi|number=(3) | |||

|top= [X]-ik | |||

|[X]-i-k | |||

|person-{{gcl|PROX}}-{{gcl|DEI}} | |||

|"this person" (Codex) | |||

}} | |||

''*so'' vs ''*h<sub>1</sub>is'' | |||

< | |||

*h0e * eah0 *as *ats | |||

**pʰirás > pʰā́r = *dʰgʰūmás > *gʰā́mar, *gʰā́man | |||

**pʰerós > *phṓr dʰ | |||

aes, eah<sub>0</sub>, ad, sa [animated distal], tad [inanimated distal], aestad, eātad, atad | |||

| Line 2,874: | Line 2,991: | ||

| Dative || -em{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}, -en{{ref|4|4}}, -e{{ref|6|6}}{{ref|7|7}} || -er{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}, -en{{ref|4|4}} || -em{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}, -en{{ref|4|4}} || -en{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}{{ref|4|4}}{{ref|6|6}}{{ref|7|7}} | | Dative || -em{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}, -en{{ref|4|4}}, -e{{ref|6|6}}{{ref|7|7}} || -er{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}, -en{{ref|4|4}} || -em{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}, -en{{ref|4|4}} || -en{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}{{ref|4|4}}{{ref|6|6}}{{ref|7|7}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Accusative || -en{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}{{ref|4|4}} || -e{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|3|3}}{{ref|4|4}}, -ie{{ref|2|2}} || -es{{ref|1|1}} | | Accusative || -en{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|2|2}}{{ref|3|3}}{{ref|4|4}} || -e{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|3|3}}{{ref|4|4}}, -ie{{ref|2|2}} || -es{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|3|3}}, -as{{ref|2|2}}, -e{{ref|4|4}} || -e{{ref|1|1}}{{ref|3|3}}, -ie{{ref|2|2}}, -en{{ref|4|4}} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 3,029: | Line 3,146: | ||

*eātad kaláh0 gʷaînah0 | *eātad kaláh0 gʷaînah0 | ||

=== | ===Pronouns [...]=== | ||

[...] | |||

====Personal Pronouns [...]==== | |||

[...] | |||

English, German, French, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Persian, Latin, Greek, Sanskrit... | |||

Brugmann; Grundriss [...] ⇒ Schmidt, Stammbildung und Flexion (argues in favor of eǵ as older tham eǵom) ⇒ P. Forchheimer, The category of person in language, Berlin 1953 | |||

⇒ Benveniste, La nature des pronoms > https://www.academia.edu/1478874/Die_komplexe_Morphologie_der_urindogermanischen_Personalpronomina_draft_ | |||

Stop Borrowing! Anatolian/Indo-European Stops, Voice, and Northwest Semitic Loans – With Notes on Ugaritic grdš, ztr, dġṯ and Other Words | |||

[...] | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | |||

! rowspan="3" | | |||

! colspan="12" | PERSONAL PRONOUN DECLENSION | |||

|- | |||

! colspan="3" | Singular | |||

! colspan="3" | Dual | |||

! colspan="3" | Plural | |||

! colspan="3" | Collective | |||

|- | |||

! 1<sup>st</sup>-person | |||

! 2<sup>nd</sup>-person | |||

! 3<sup>rd</sup>-person | |||

! 1<sup>st</sup>-person | |||

! 2<sup>nd</sup>-person | |||

! 3<sup>rd</sup>-person | |||

! 1<sup>rd</sup>-person | |||

! 2<sup>nd</sup>-person | |||

! 3<sup>rd</sup>-person | |||

! 1<sup>rd</sup>-person | |||

! 2<sup>nd</sup>-person | |||

! 3<sup>rd</sup>-person | |||

|- | |||

! Nominative | |||

| *h<sub>5</sub>ih<sub>1</sub>ṓn || *tū́ ~ *táu || *aī́h<sub>0</sub>i<br>*aī́h<sub>0</sub><br>*aī́ts || *ōi̯ṓn || *ūi̯ū́ || *aīaī́<br>*īu̯ī́h<sub>0</sub><br>*īu̯ī́ || *ṓns || *ū́s || *aī́s<br>*ī́h<sub>0</sub>s<br>*ī́s || *ṓna || *ū́a || *aī́a<br>*ī́h<sub>0</sub>a<br>*ī́a | |||

|- | |||

! Accusative | |||

| *nh<sub>0</sub>(m) || *tu̯h<sub>0</sub>(m) || *im<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>m<br>*its || *noh<sub>0</sub>(m) || *i̯uh<sub>0</sub>(m) || *aim,<br>*aih<sub>0</sub>m,<br>*aits || *nsh<sub>0</sub>(m) || *u̯sh<sub>0</sub>(m) || *ism<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>sm<br>*is || *nah<sub>0</sub>(m) || *u̯ah<sub>0</sub>(m) || *iam<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>am<br>*ia | |||

|- | |||

! Genitive | |||

| *ni̯a || *tu̯i̯a || *itsi̯a<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>tsi̯a<br>*itsi̯a || *noi̯a || *i̯ui̯a || *aitsi̯a,<br>*aih<sub>0</sub>tsi̯a,<br>*aitsi̯a || *nsi̯a(m) || *u̯si̯a(m) || *itsi̯am<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>tsi̯am<br>*itsi̯am || *nai̯a || *u̯ai̯a || *iai̯a<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>ai̯a<br>*iai̯a | |||

|- | |||

! Locative | |||

| *ni || *tu̯i || *itsi<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>tsi<br>*itsi || *noi || *i̯ui || *aitsi<br>*aih<sub>0</sub>tsi<br>*aitsi || *nsi(m) || *u̯si(m) || *itsim<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>tsim<br>*itsim || *nai || *u̯ai || *iai<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>ai<br>*iai | |||

|- | |||

! Dative | |||

| *nai̯ || *tu̯ai̯ || *iai̯<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>ai̯<br>*iai̯ || *noai̯ || *i̯uai̯ || *aiai̯<br>*aih<sub>0</sub>ai̯<br>*aiai̯ || *nsai̯(m) || *u̯sai̯(m) || *isai̯(m)<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>sai̯(m)<br>*isai̯(m) || *naai̯ || *u̯aai̯ || *iaai̯<br>*ih<sub>0</sub>aai̯<br>*iaai̯ | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

''* | *The first-person singular ''*h<sub>5</sub>ih<sub>1</sub>ṓn'' (PIE ''*h<sub>1</sub>eǵHóm'') seems to be a descendent of the primordial form ''ˈʕih-ɔː'' "I" , which would regularly yield stress on the first syllable, yet it is observed that in PIE the consonant <''*ǵ''> appears (probably a consequence from the sound change '''*h<sub>1</sub> ⇒ *ǵ / V_V'''), plus the affixation of <''*n''>, a borrowing from Diluvian ''nao'' "this person". | ||

**In PIE, the emphatic ''*h<sub>1</sub>eǵHóm'' could be interpreted as more archaic than ''*h₁eǵH'', as Homeric Greek ''ἐγών'' and Sanskrit ''अहम्'' suggest. The emphatic particle ''*-om'' (PIE) likely arose due the contaminator <''*m''>. | |||

**The nasal in ''*h<sub>5</sub>ih<sub>1</sub>ṓn'' "I" became <''*m''> primarily due two distinct processes; one phonetic and other phonological. It was either subsequently labialized by the preceding vowel, shortening the nucleus (i.e. /oːn/ ⇒ /own/ ⇒ /om/), and/or swapped by the contaminator ''*m'' based on its inflected forms. | |||

***This sound change affected all other inflections of the first person singular (e.g. ''*nh<sub>0</sub>(m)'' "me" (A) ⇒ ''*mh<sub>0</sub>'' ~ ''*h<sub>0</sub>m'' "me" (?) ⇒ ''*me'' ~ ''*h<sub>1</sub>me'' "me" (PIE)). | |||

*The second-person singular ''*tū́'' (PIE ''*túH'') seems to be a descendent of Diluvian ''taocar'' "the person one refers to", with an unusual vocalic paradigm. If this is correct, a more conservative alternative might have been ''*táu''. | |||

**In PIE, the pronoun ''*túH'' is extremely conservative, found as ''tu'' in Latin, ''σύ'' in Greek, and ''त्वम्'' in Sanskrit, for example. In PIA, though, Hittite ''zīg'' and Palaic ''ti'' suggest Indo-Anatolian ''*tī́''<ref name=Kloekorst>Alwin Kloekorst (2007); [https://archive.org/details/etymological-dictionary-of-the-hittite-inherited-lexicon/mode/1up ''Etymological Dictionary Of The Hittite Inherited Lexicon'']</ref>; although it could also be pointed out that the Anatolitan counterparts might be mere rearrangements from the non-emphatic PIE 1.SG.NOM. ''*h<sub>1</sub>eǵ(ō)'' plus an accusative enclitic of the second-person singular (i.e. ''*te-eǵ'' ⇒ ''*tī́ǵ'' (PA))<ref name=Szemerényi>Oswald Szemerényi (1990); [https://archive.org/details/szemerenyieinfuhrungindievergleichendesprachwissenschaft4thedition1990/mode/2up ''Einführung in die vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft'']</ref><ref name=Petersen>Walter Petersen (1930); [https://www.jstor.org/stable/409118?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents ''The Inflection of Indo-European Personal Pronouns'']</ref>, or even the result of the palatalization of apical consonants due phonetic height (i.e. ''*tū'' (PIA) ⇒ ''*tyū'' (?) ⇒ ''*tī'' (PA))<ref name=Melchert>Craig Melchert (1983); [https://linguistics.ucla.edu/people/Melchert/2ndsingularpronoun.pdf ''The Second Singular Personal Pronoun in Anatolian'']</ref>. | |||

*The third-person singulars ''*aī́h<sub>0</sub>i'', ''*aī́h<sub>0</sub>'', and ''*aī́ts'' possess a shorter form when complemented by a noun (e.g. ''*aī́h<sub>0</sub>i'' "he" ⇒ ''*h<sub>0</sub>naī́r h<sub>0</sub>i'' "he, the man"). The reason for this is that in the Codex, pronouns used to be morphologically treated as affixes, and therefore couldn't stand by themselves except when linked to a root (e.g. ''ˈə-e̞ː'' "he/she/it", but not ''**e̞ː''). | |||

**As a result, the clitic counterparts gained a sense as proximal demonstratives in PIE, being evident in forms such as Latin ''is'' "he", ''ea'' "she", and ''id'' "it", whose anaphoric use prohibts them to stand by themselves. | |||

***e.g. ''*h<sub>0</sub>í'' "he" ⇒ ''*h<sub>1</sub>í'' "this/he"; ''*íh<sub>0</sub>'' "she" ⇒ ''*h<sub>1</sub>íh<sub>2</sub>'' "this/she"; ''*íts'' "it" ⇒ ''*h<sub>1</sub>íd'' "this/it". | |||

*Overall, the dual is formed by erasing sounds of the singular, then reduplicating it (e.g. ''*h<sub>5</sub>ih<sub>1</sub>ṓn'' ⇒ ''*ōi̯ṓn''; ''*tū́'' ⇒ ''*ūi̯ū́''; ''*aī́h<sub>0</sub>i'' ⇒ ''*aīaī́''), while the plural is formed by erasing the reduplication of the dual, then adding the serial particle ''*-s-'' (e.g. ''*ōi̯ṓn'' ⇒ ''*ṓns''; ''*ūi̯ū́'' ⇒ ''*ū́s''; ''*aīaī́'' ⇒ ''*aī́s''), and the collective simply does the latter but with the suffix ''*-a'' (e.g. ''*ōi̯ṓn'' ⇒ ''*ṓna''; ''*ūi̯ū́'' ⇒ ''*ū́a''; ''*aīaī́'' ⇒ ''*aī́a''''). Medial ''*i̯'' ~ ''*u̯'' is inserted to avoid diphthongs between reduplicated vowels, and ''*ts'' is applied in other cases when two bordering vowels are similar (except those involving schwas). | |||

**Rather than the nominative of the first and second-person dual/plural in PIE being prehistorical combinations (i.e. ''*u'' 2.SG + ''*e'' 1.SG. + = ''we'' 1.DU./PL.; ''*i'' 3.SG. + ''*u'' 2.SG = ''*yu'' 2.DU./PL.)<ref name=Seebold>Elmar Seebold (1984); [https://annas-archive.org/md5/e8ece7cab77fe9adeae0052312aa3d89 ''Das System der Personalpronomina in den frühgermanischen Sprachen: Sein Aufbau und seine Herkunft'']</ref>, the dual products of the Aryan patterns would eventually substitute the plural forms of the first and second-person in their nominative equivalents (i.e. ''*ṓns'' "we (plural)" ⇒ ∅, replaced by ''*ōi̯ṓn'' "we (dual)" (A) ⇒ ''*wéy'' "we (plural)" (PIE); ''*ūs'' "you (plural)" ⇒ ∅, replaced by ''*ūi̯ū́'' "you (dual)" (A) ⇒ ''*yū́'' "you (plural)" (PIE)), while their oblique inflections for example would assume other spots in the ancestor of Indo-European languages (i.e. ''*noh<sub>0</sub>(m)'' 1.DU.ACC. (A) ⇒ ''*n̥h<sub>1</sub>wé'' ~ ''*nōh<sub>1</sub>'' 1.DU.ACC. (PIE); ''*i̯uh<sub>0</sub>(m)'' 2.DU.ACC. (A) ⇒ ''*uh<sub>1</sub>wé'' ~ ''*wōh<sub>1</sub>'' 2.DU.ACC. (PIE)). | |||

**The particle <''*m''> gains the property of the serial particle <''*s''> when the latter conflates with the particle ''*ts'' (e.g. third-person plural locative ''*itsim'' instead of ''*itsis''). This contamination was likely encouraged due the abundant presence of ''*m'' in the accusative, and produces an alternative explanation to the hypothesis that the oblique of the first-person plural was''*ms-'' before becoming ''*ns-''<ref name=Sihler>Andrew Sihler (1995); [https://archive.org/details/sihler-andrew-new-comparative-grammar-of-greek-and-latin/mode/2up ''New Comparative Grammar Of Greek And Latin'']</ref>. Later in PIE, not only plural forms (e.g. ''*nsai̯(m)'' 1.PL.DAT. (A) ⇒ ''*n̥sméy'' 1.PL.DAT. (PIE)) would become contaminated, but also singular ones (e.g. ''*iai̯'' "to him" (A) ⇒ ''*h<sub>1</sub>esmōy'' "to him" (PIE)); including verbal affixes (e.g.''*-nas'' 1.PL.VB. (A) ⇒ ''*-mos'' 1.PL.VB. (PIE)). | |||

====Possessive Pronouns==== | |||

nás, tu̯ás, h0iás/ih0ás/i ... tsu̯á | |||

in Aryan possessive pronouns could be produced through the pure oblique or any inflected form, as long as it received the affix -ás. | |||

nás ~ nai̯ás ~ ni̯aás ~ niás | |||

nás h0naír | |||

compare the translation for "my man" | |||

''*nh0(m)ás h0naī́r'' (A) > ''*h1mós h2nḗr'' (PIE) > ''ἐμός ἀνήρ'' (G) | |||

-as -ah0 -am | -aī -ah0ī -aī | |||

-ias -i | -īas īs | |||

-h0i -ih0 -its | -h0ias -ih0as -itsas | |||

====Reflexive Pronouns==== | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | |||

! rowspan="2" | | |||

! colspan="4" | REFLEXIVE PRONOUN DECLENSION | |||

|- | |||

! Singular | |||

! Dual | |||

! Plural | |||

! Collective | |||

|- | |||

! Nominative | |||

| *tsū́r ~ *tsáur || *ūi̯ū́r || ū́rs || *ū́ra | |||

|- | |||

! Accusative | |||

| *su̯h<sub>0</sub> || *ruh<sub>0</sub> || *u̯rsh<sub>0</sub> || *u̯rah<sub>0</sub> | |||

|- | |||

! Genitive | |||

| *su̯i̯a || *rui̯a || *u̯rsi̯a || *u̯rai̯a | |||

|- | |||

! Locative | |||

| *su̯i || *rui || *u̯rsi || *u̯rai | |||

|- | |||

! Dative | |||

| *su̯ai̯ || *ruai̯ || *u̯rsai̯ || *u̯raai̯ | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

- | *The reflexive pronoun ''*tsū́r'' derives from an older ''*ū́tsar'' (equivalent to Aryan ''*aítsar'' "this/that one", PIE ''*h<sub>1</sub>íteros'' "(an)other"), itself a borrowing from Diluvian ''aocar'', whose <''*ū́''> portion is still visible in another borrowing into Aryan (i.e. the second-person singular ''*tū́''). | ||

**In PIE, it was reanalyzed as its accusative form (i.e.''*su̯h<sub>0</sub>'' "themselves" ⇒ ''*swé'' "themselves"), thus degrading the dual, plural, and collective inflections. | |||

====Demonstrative Pronouns==== | |||

[..] | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | |||

! rowspan="3" | | |||

! colspan="12" | PRONOUN DECLENSION | |||

|- | |||

! colspan="3" | Singular | |||

! colspan="3" | Dual | |||

* | ! colspan="3" | Plural | ||

! colspan="3" | Collective | |||

* | |- | ||

! Masculine | |||

* | ! Feminine | ||

* | ! Neuter | ||

! Masculine | |||

! Feminine | |||

! Neuter | |||

! Masculine | |||

! Feminine | |||

! Neuter | |||

! Masculine | |||

! Feminine | |||

! Neuter | |||

|- | |||

! Nominative | |||

| *h<sub>0</sub>tsar|| *tsah<sub>0</sub>r || *tsar || *h<sub>0</sub>tātā || *tātāh<sub>0</sub> || *tātā || *h<sub>0</sub>tās || *tāh<sub>0</sub>s || *tās || *h<sub>0</sub>tāa || *tāh<sub>0</sub>a || *tāa | |||

|- | |||

! Accusative | |||

| *tam || *tah<sub>0</sub>m || *tats || *atam || *atah<sub>0</sub>m || *atats || *tasm || *tah<sub>0</sub>sm || *tas || *tam || *tah<sub>0</sub>am || *taa | |||

|- | |||

! Genitive | |||

| *tai̯a || *tah<sub>0</sub>i̯a || *tai̯a || *atai̯a || *atah<sub>0</sub>i̯a || *atai̯a || *tasi̯a || *tah<sub>0</sub>si̯a || *tasi̯a || *taai̯a || *tah<sub>0</sub>ai̯a || *taai̯a | |||

|- | |||

! Locative | |||

| *tai || *tah<sub>0</sub>i || *tai || *atai || *atah<sub>0</sub>i || *atai || *tasi || *tah<sub>0</sub>si || *tasi || *taai || *tah<sub>0</sub>ai || *taai | |||

|- | |||

! Dative | |||

| *taai̯ || *tah<sub>0</sub>ai̯ || *taai̯ || *ataai̯ || *atah<sub>0</sub>ai̯ || *ataai̯ || *tasai̯ || *tah<sub>0</sub>sai̯ || *tasai̯ || *taaai̯ || *tah<sub>0</sub>aai̯ || *taaai̯ | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

''*-tsaras'' (emphatic affix) ⇒ ''*-teros'' (emphatic affix), with the demonstrative sense shown in ''*aítsaras'' "one there" ⇒ ''*h<sub>1</sub>íteros'' "(an)other" | |||

tsar > *só "that" | |||

-om (emphatic) | |||

-tar (loc.) | |||

*íta "there/then/thus" | |||

*h1itH "thus" EX: ita | |||

*h1idH "here" EX: ibi | |||

*tor "there" | |||

tso | |||

-r "locative" | |||

ítar > h1itH | |||

tsatar "that > tor | |||

h0tā́a > h1etṓa > tóy | |||

táa > téa > teh2 | |||

h0 may become h1 as <e> or h2 as <a> | |||

*aī́h0i, *aī́h0, *aíts > *h0i, *ih0, *its | |||

*h5ílias, *h5íli > *lis, li | |||

specialized/not | |||

as this segment results in 6 possibilities | |||

ʕih > ~ h5ī ~ aī ~ aih1 ~ h5ih1 ~ ai ~ i | |||

*All demonstratives of the ''*-ias'' paradigm transitioned from animate/inanimate to masculine/feminine/neuter declension. | |||

**Either through the tonic form (e.g. "other" ''*h<sub>5</sub>ílias'', ''*h<sub>5</sub>íli'' (Aryan) ⇒ ''*h<sub>2</sub>élyos'', ''*h<sub>2</sub>élyeh<sub>2</sub>'', ''*h<sub>2</sub>élyod'' (PIE)), or the clitic form (e.g. "this" ''*kis'', ''*ki'' (from Aryan ''*h<sub>5</sub>íkias'', ''*h<sub>5</sub>íki'') > ''*ḱís'', ''*ḱíh<sub>2</sub>'', ''*ḱíd'' (PIE)). | |||

====Interrogative Pronouns==== | |||

[..] | |||

====Indefinite Pronouns==== | |||

[..] | |||

====Relative Pronouns==== | |||

[..] | |||

===Verb=== | |||

[...] | [...] | ||

====Aspect==== | |||

The Origin of Aspect in the Indo-European Languages Oswald Szemerényi | |||

====?==== | |||

[ | ''*gaínōm'', ''*gígnmi'' "I generate" | ||

''*pūhāṓm'', ''*píbmi'' "I drink" | |||

''*wehdḗyōm'', ''*wḗydmi'' "I see" | |||

*gánas > γόνος "offspring" | |||

Initial clusters in the Nominative will give way to /ə/<br> | |||

*ptā́r (A)> *patḗr (PIE)<br> | |||

*páh5man > *póh5mn̥ > πῶμα "slid"<br> | |||

[*peh5] "feed, protect" | |||

''*pʰair-'' "bearing" [n/v] (Latin ferō, Greek φέρω < ''*pʰaírōm'', ''*pʰíprmi'') > ''*pʰaíras'' [bare noun], ''*pʰ∅rás'' "bearer" [adjective-noun] (Latin fūr, Greek φώρ "thief"), ''*pʰáras'' [result-noun] (Greek φόρος "tribute") | |||

''*daim-'' "building" [n/v] (Greek δέμω < ''*daímōm'', ''*dídmmi'') > ''*daímas'' [bare noun], ''*d∅más'' "building" [adjective-noun] (Greek δῶ "house"), ''*dámas'' "house" [result-noun] (Latin domus, Greek δόμος "house") | |||

''*paid-'' "stepping" [n/v] (''*paídōm'', ''*pípdmi'') > ''*paídas'' [bare noun], ''*p∅dás'' "foot" [adjective-noun] (Latin pes, Greek πούς "foot"), ''*pádas'' "step" [result-noun] | |||

''*kpain-'' "killing" [n/v] (Proto-Indo-European *kʷʰen, Latin de-fendo "I expell from") > ''*kpaínas'' [bare noun], ''*kp∅nás'' "murderer" [adjective-noun], ''*kpánas'' "murder" [result-noun] (Greek φόνος "murder") | |||

''*h<sub>1</sub>ed-'' "eating" [n/v] (German esse, Russian ем, Latin edō, Greek ἔδω < ''*h<sub>1</sub>édōm'', ''*yédmi'') > ''*h<sub>1</sub>édas'' [bare noun], ''*yedás'' "eater" [adjective-noun], ''*h<sub>1</sub>ádas'' [result-noun] | |||

In Aryan, personal enclitics are positioned after the first word of a proposition (Wackernagel's Law) | |||

... | |||

the verb either starts or ends the clause... tendence to follow SOV | |||

*the finite verb loses accent in an independent clause, except when in first position (always has accent in dependent clause) | |||

*absolute construction | |||

*subject is ommitted | |||

*na pʰaírīt mai | |||

*pʰaírīt mai na? | |||

h<sub>5</sub>ígōm, mayás, mai | |||

_(negation=subject/int.pronoun/accented verb)-_()-_(unaccented verb) | |||

The most comprehensive summary available on PIE morphosyntax was written by Matthias Fritz in Indo-European Linguistics (Michael Meier-Brügger, 2003), pp. 238-276. | |||

Winfred Philipp Lehmann’s Proto-Indo-European Syntax (1974) | |||

morphological cylce (Hock and Joseph, 1996) | |||

Szemerényi 1957: 119; Kuryłowicz 1964: 233; Rasmussen 1999: Meier-Brügger | |||

-ōm/mi | |||

-āṓm/-mā | |||

*pʰaír- | |||

-ōm / *-mi (perfective) | |||

*-āṓm / *-āmi (perfective) | |||

í (animated nouns) | |||

ì (inanimate nouns) *neuter nouns and vocatives have recessive accent | |||

Aryan has a complex system of accent loss | |||

As Greek neuter nouns possess recessive accent (especially the monosyllabic ones, which when accented, carry a circunflex) | |||

*paid- ... *p∅dás | |||

*p∅dás > páds > póds | |||

*p∅dás > *póds > pēs, πούς | |||

*p∅dasyás > *pedés > pedis, ποδός | |||

iacio ((H)yéh₁k-yoh₂) | |||

iaceo (*(H)ih₁k-éh₁yoh₂) | |||

aeykīōm > (H)yéh₁k-yoh₂ | |||

əi̯Hk > heyk /hei̯k/ > (H)yeh1(k) | |||

-éh₁- passive/stative (intransitive) suffix > -éh₁mi, -éh₁si, -éh₁ti | |||

-ye- transitive suffix > -yoh₁, -yesi, -yeti | |||

-éh₁-ye- passive/stative transitive suffix | |||

-é-ye- causative transitive suffix | |||

-eh₂- (nominal suffix) | |||

-yé- intransitive suffix > -yóh₂, -yési, -yéti | |||

-eh₂-yé- frequentative suffix | |||

- | |||

*h₂er-éh₁mi "I am arranging" > *h₂reh₁-yoh₁ "I am counting, thinking" | |||

Latin reor "I think" < PIE *h₂réh₁-yoh₁ "I count" | |||

*h₂er- "fix/put in order" | |||

*h₂reh₁ "think"< *h₂er- (“to join; to prepare”) + *-éh₁ | |||

==Syntax== | |||

It goes without saying that orthographic implications are disregarded. In French, for example, the past participle agrees in gender and number if the direct object precedes it (e.g. ''ils auraient hérité la maison'' "they would have inherited the house" et ''ils l'auraient héritée'' "they would have inherited it (the house)"), but the choice between ''-é'', ''-ée'', and ''-ées'' in the participle is ultimately irrelevant phonetically speaking. | |||

почему? | |||

I am still here | |||

Je suis encore ici | |||

Ich bin noch hier | |||

Я '''все''' ещё здесь | |||

Hic adhuc sum | |||

absolutive of "that" yields "if" | |||

Ich dachte, dass ich der Einzige war, der darüber nachdachte | |||

Я думал я один кто об этом подумал... | |||

sie sagen, dass morgen will ich arbeiten, um Geld zu verdienen; ich, wer wusste nichts darüber | |||

ils disent que demain je veux travailler pour gagner d'argent; moi, qui n'y savais rien pas | |||

Subordinate clause... in German, Russian, Latin, and Greek: | |||

:''Sie sagen, dass morgen will ich arbeiten, um Geld zu verdienen.'' | |||

:''Они говорят, что завстра я хачу работат, чтобы зарабатывать деньге.'' | |||

:''Illi dicent me cras laborare volo ut pecuniam meream.'' | |||

:They say I want to work tomorrow in order to earn money. | |||

The hypothetical in French is marked by the imperfect indicative, whereas in Portuguese by the imperfect subjunctive; in German by an auxiliary verb linking the infinite form, while in English the bare preterite states the sense; and Russian applies a conditional/optative particle of subjunctive mood in conjunction with the past tense: | |||

: ''Il serait ennuyeux si ils nous '''reconnaissaient''''' [French] | |||

: ''Seria irritante se eles nos '''reconhecessem''''' [Portuguese] | |||

: ''Es wäre ärgerlich, wenn sie uns '''erkennen würden''''' [German] | |||

: ''It would be annoying if they '''recognized''' us'' [English] | |||

: ''было бы досадно, если '''бы''' они нас '''узнали''''' [Russian] | |||

Ancient indo-european languages, furthermore ... general use of imperfect subjunctive in Latin, while present and aorist optatives in Greek's protasis and apodasis respectively: | |||

: ''molestus esset si nos '''recognoscerent''''' [Latin] | |||

: ''εἴη ὀχληρός ἄν, εἰ ἡμᾶς '''ἐπιγνοῖεν''''' [Greek] | |||

: ... [Sanskrit] | |||

An areal feature of Standard Average Euroepan is the [...] The perfect in West Germanic Languages such as English and German requires a past participle to be modified by either the verb "to be" or "to have": | |||

: ''ich bin ins Haus '''gewesen''''' [German] | |||

: ''I have '''been''' in the house'' [English] | |||

What determines the use of "to be" or "to have" is the distinction between "motionless" and "motive" verbs, as seen in French and German: | |||

: ''je '''suis''' allé à la maison'' [French] | |||

: ''ich '''bin''' nach Hause gegangen'' [German] | |||

In German, the auxiliary ''werden'' is obligatory in the passive voice: | |||

''Ich werde gezwungen, die Wahrheit zu zählen'' [German] | |||

[...] | |||

: ''als ob du auf der Flucht gewesen wärst'' | |||

: ''as if you had been on the run'' | |||

[...] | |||

: ''er lehnte es ab, sich zu der sogennanten Affäre zu beschreiben'' | |||

===Implications of agreement=== | |||

There is a tendence for heavy agreement to lead to lax syntax. Vide the Latin sentence, wherein cases reprove ambiguity: | |||

: ''Maenala trānsieram latebrīs horrenda ferārum'' [Latin<ref name=Ovidius>Ovidius; [https://hypotactic.com/latin/index.html?Use%20Id=met1 Metamorphoses]; 1.216</ref>] | |||

:: "I had travelled over horrendous Maenalus, through the lairs of beasts" | |||

Oddities in agreement, on the other hand, reveal oddities in syntax. In Portuguese, for example, the relative determiner ''cujo/cuja'' necessarily precedes the noun, yet the equivalent genderles expression ''ao qual'' allows the noun to be farther away into the clause. Likewise, in French, the relative determiner ''dont'' doesn't agree with the noun, and therefore can be separated as well. Compare the translation of "the man whose existence I do not know" in both instances and languages: | |||

(1) ''o homem '''cuja existência''' eu não conheço'' [Portuguese] | |||

: ''l'homme '''dont''' '''l'existence''''' je ne connais pas [French] | |||

(2) ''o homem '''ao qual''' eu não conheço a '''existência''''' [Portuguese] | |||

: ''l'homme '''dont''' je ne connais pas '''l'existence''''' [French] | |||

===Enclitics=== | |||

[...] | |||

By examining a large corpus of hellenic texts, Jakob Wackernagel stated in his essay how enclitics in Greek sentences are mostly located in the second position<ref name=Wackernagel>Jakob Wackernagel (1892); [https://archive.org/details/indogermanischef01berluoft/page/332/mode/2up ''Über ein Gesetz der indogermanischen Worstellung'']</ref>. For example, he contrasted specifically the accusative of the first-person pronoun in the isolated (''ἐμέ'') and enclitic (''με'') forms: | |||

<blockquote>Besonders belehrend sind aber die paar Inschriften mit ''ἐμέ''. Zweimal steht dieses ''ἐμέ'' auch an zweiter Stelle: IGA. 20,8 (Korinth) ''᾿Απολλόδωρος ἐμὲ ἀνέθ[ηκε]'' und Gazette archéol. 1888 S. 168 ''Μεναΐδας ἐμ’ ἐποί(ϝ)εςε Χαρόπ(ι)''. Aber sechsmal steht ''ἐμέ'' anders: Klein S.39 ''Ἐξηκίας ἔγραψε κἀπόηςε ἐμέ'' (Vers?) 5. 40 ''Ἑξηκίας ἔγραψε κἀ(ι)ποίης᾽ ἐμέ'' (Vers?). S.''ΟῚ Χαριταῖος ἐποίηςεν ἔμ᾽ εὖ''. 8. 82 ''Ἑρμογένης ἐποίηςεν ἐμέ''. 8.85 ''Ἑρμογένης ἐποίηςεν ἐνέ'' (liess ''ἐμέ''). S. 85 ''Σακωνίδης ἔγραψεν ἐμέ''. Diese Stellen zeigen, dass die regelmässige Stellung von ''με'' hinter dem ersten Wort nicht zufällig und dass sie durch seine enklitische Natur bedingt ist. [Vgl. noch die Nachträge.]</blockquote> | |||

===?=== | |||

A riddle in German: | |||

: ''Der Vater ist noch nicht geboren,'' | |||

: ''der Sohn ist schon auf dem Dache.''<ref name=Aarne>Anti Aarne (1918-1920); [https://digitalisate.sub.uni-hamburg.de/recherche/detail?tx_dlf%5Bdouble%5D=0&tx_dlf%5Bid%5D=48996&tx_dlf%5Bpage%5D=32&tx_dlf_navigation%5Baction%5D=main&tx_dlf_navigation%5Bcontroller%5D=Navigation&cHash=7cd75d7f3224787416091debb4db9c9a Vergleichende Rätselforschungen]</ref> | |||

:: The father is not yet born, | |||

:: the son is already on the roof. | |||

A riddle in French: | |||

: ''Blanc est le champ,'' | |||

: ''noire est la semmence,'' | |||

: ''l'homme qui le semme,'' | |||

: ''est de très grand science.''<ref name=Aarne>Anti Aarne (1918-1920); [https://digitalisate.sub.uni-hamburg.de/recherche/detail?tx_dlf%5Bdouble%5D=0&tx_dlf%5Bid%5D=48996&tx_dlf%5Bpage%5D=32&tx_dlf_navigation%5Baction%5D=main&tx_dlf_navigation%5Bcontroller%5D=Navigation&cHash=7cd75d7f3224787416091debb4db9c9a Vergleichende Rätselforschungen]</ref> | |||

:: White is the field, | |||

:: black is the seed, | |||

:: the man who seeds it, | |||

:: is of great science. | |||

dd | |||

imperfect: I am running [action started but not halted, not necessarily intended to be completed] | |||

imperfective: I am running [action started but not halted, has yet to be completed] | |||

perfect: I have run [action started and halted, not necessarily completed] | |||

perfective: I have run [action started and completed] | |||

*the syntax of a language is marked by its idiosyncratic constructions | |||

il semblerait qu'ils se soient intensifiés | |||

parece (por hypóthese) que eles se intensificaram | |||

movement verbs and cases: cubitum ire *as French and German treat it in the european sprachbund | |||

eo domum | |||

end goal: accusative | |||

*h2iyṓm dámam | |||

[[w:Standard average european||europoid]] | |||

какой-то сказал | |||

in dem Anfang, hat Gott die Erde und den Himmel geschaffen | |||

Männer, deren Kinder gestorben haben, | |||

der Schicksal dessen, der gelitten habt | |||

der Schicksal derer, die gelitten haben | |||

Ja vot tut ... | |||

==Sample text== | |||

==References== | |||

Einleitung in die Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft (Pott) | |||

hermann hirt Indogermanische Grammatik | |||

Franz Bopp | |||

Schleicher | |||

Calvert Watkins | |||

Jochem Schindler | |||

Helmut Rix | |||

Kuryłowicz | |||

Boisacq : É. Boisacq, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque. Heidelberg, 1916. | |||

Brugmann, Griech. Gram?: Griechische Grammatik, | |||

Chantraine, GH: Grammaire homérique. | |||

Chantraine, Morphologie : Morphologie historique du grec. 1947. 2nd ed. 1961. | |||

Chantraine, Formation ` La formation des noms en grec ancien | |||

CIL : Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. | |||

Collitz-Bechtel, D: Sammlung griechischer Dialektinschriften. 1884— 1915 | |||

Egli, Heteroklisie im Griechischen: J. Egli, Heteroklisie im Griechischen, mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Fälle von Gelenkheteroklisie. Dissert. Zürich | |||

Ehrlich, Betonung ` Untersuchungen über die Natur der griechischen Betonung. 1912 | |||

Ernout-Meillet, Dictionnaire étym.: Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine | |||

Evidence for Laryngeals : Evidence for Laryngeals — Work papers of a conference in Indo—European linguistics on May 7 and 8, 1959. Edited by Werner Winter. Austin, Texas, 1960 | |||

Frisk, GEW ` Griechisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. Heidelberg 1954 | |||

Kuryłowicz, A pophonie ` L'apophonie en indo-européen. 1956. | |||

Kuryłowicz, Accentuation *: L'accentuation des langues indo—européennes. 2nd ed. 1958. | |||

Leumann-Hofmann :M. Leumann-]. B. Hofmann, Lateinische Grammatik, 5th ed. 1926-8 | |||

Meillet, Zz£roduction 9: Introduction a l'étude comparative des langues indo-européennes. 8th ed. 1937 | |||

Pokorny : Pokorny, /wdogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. 1948- | |||

Wackernagel (-Debrunner), AzGr. : Altindische Grammatik | |||

Bergaige, Abel; Du Rôle de la dérivation dans la déclinaison indo-européenne: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k57721099.texteImage# | |||

Bergaige, Abel; Essai sur la construction grammaticale considérée dans son développement historique, en sanscrit, en grec, en latin, dans les langues romanes et dans les langues germaniques: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5803410m/f6 | |||

> | |||

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.322486/mode/2up | |||

https://archive.org/details/sanskritgrammari00whituoft/page/xx/mode/2up?view=theater | |||

https://archive.org/details/AGrammarOfModernIndo-european/page/n1/mode/2up?view=theater&q=determiner | |||

*Behaghel, Otto (1932), ''Deutsche Syntax'' | |||

*Brugmmann, Karl (1925), ''Die syntax des einfachen satzes im indogermanischen'' | |||

*Brugmmann; Delbrück (1889), ''Grundriss der vergleichenden grammatik der indogermanischen sprachen'' | |||

*Benveniste, Émile (1935), ''Les Origines de la Formation des Noms en Indo-Européen'' | |||

*Collinge, N. E. (1985), ''The Laws of Indo-European'' | |||

*Jespersen , Otto (1924), ''The Philosophy Of Grammar'' | |||

*Priscianus (6th Century), ''Institutiones Grammaticae'' | |||

*Sütterlin, Ludwig (1908), ''Die Lehre von der Lautbildung'' | |||

*Sommerstein, Alan (1973), ''Sound Pattern of Ancient Greek'' | |||

*Thomasus Erfordiensis (13th Century), ''Tractatus de Modis Significandi seu Grammatica Speculativa'' | |||

*Kortlandt. Frederik H.H. (1983). “Proto-Indo-European Verbal Syntax”. In: Journal of Indo-European Studies 11, 307–324. | |||

*https://www.academia.edu/37684312/On_the_origin_of_grammatical_gender | |||

The Precursors of Proto-Indo-European (Kloekhorst, Pronk | |||

Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon (Derksen) | |||

Etymological Dictionary of the Hittite Inherited Lexicon (Kloekhorst) | |||

Etymological Dictionary of Latin (de Vaan) | |||

Etymological Dictionary of Greek (Beekes) | |||

Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic (Kroonen) | |||

A Concise Etymological Sanskrit Dictionary (Mayrhofer) | |||

The Indo-European Languages (Kapović) | |||

Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics 1, 2, 3 (Klein, Joseph, Fritz) | |||

The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European (Mallory, Adams) | |||

https://www.academia.edu/117830047/Stop_Borrowing_Anatolian_Indo_European_Stops_Voice_and_Northwest_Semitic_Loans_With_Notes_on_Ugaritic_grd%C5%A1_ztr_d%C4%A1%E1%B9%AF_and_Other_Words | |||

https://archive.org/details/bomhardtheoriginsofprotoindoeuropean/page/n1/mode/2up | https://archive.org/details/bomhardtheoriginsofprotoindoeuropean/page/n1/mode/2up | ||

Latest revision as of 20:32, 7 February 2026

| Aryan | |

|---|---|

| *Airás | |

Models of indo-european migrations hypothesizing the proto-language to pertain to a range between 7000 to 4000 BC | |

| Pronunciation | [əi̯ˈrəs] |

| Created by | Veno |

| Setting | Caucasus Mountains |

| Era | c.10,000–8,000 BC |

Pangaean Code

| |

Early form | Transitional Dialect

|

Map of areas where Aryan is believed to have once been spoken | |

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

Aryan (*Ai̯ri̯áh0, [əi̯ˈri̯əʔ]), also referred to as Pre-Proto-Indo-European, is an ab interiori language depicting the transition from Paleolithic Codes to Proto-Indo-European (PIE). There are no historical records of its existence, or comparative data to support it; rather, it is an abductive experiment based on the hypothesis of Transitional Dialects.

In most of known History, indo-european speaking populations have been widespread in Eurasia, bearing fruits from civilizations such as those of the Roman Empire, the Hellenistic City-States, and the Rigvedic Tribes. Memorable personalities who spoke natively dialects from those areas include the roman general Julius Caesar (speaker of Latin), the macedonian king Alexander the Great (speaker of Ancient Greek), the nazi chancellor Adolf Hitler (speaker of German), the french emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (speaker of Corsican), the british physicist Isaac Newton (speaker of English), the italian renascentist Leoanardo da Vinci (speaker of Tuscan Italian), the indian ascetic Gautama Buddha (speaker of Prakrit), et cetera. Also, due the trajectory of the linguistic stock along the millenia, some of the most culturally influential works of Literature have been yielded, such as the Vulgate, the Iliad, and the Vedas. As of the 21st Century, half of the world's population speaks 454 indo-european languages[1], with the Americas, Europe, Iran, Pakistan, and India being today the centers of native speakers due the Indo-European Migrations and European Colonialism.

Naturally, the origin of the indo-european family has attracted the curiosity of thousands of researchers in the last centuries, since William Jones' presidential discourse to the Asiatic Society in 1786[2], which famously addressed the similarity between Sanskrit and european languages. Further works that [...]

In the hybrid model, Aryan must have been spoken somewhere near the Caucasus Mountains in compliance with the Armenian Hypothesis, which in its current form holds that the speakers of "Pre-Proto-Indo-European" pertained to the genepool of the Caucasian Hunter-Gatherers (CHG)[3], who would eventually contribute to the formation of the Yamnaya Culture and the dispersion of "Core Proto-Indo-European" as detailed in the Kurgan Hypothesis. The age of the language is more controversial, being set between 12,000 and 10,000 years Before Present (BP), or the double of its daughter-language's, to coincide with the notion of Linguistic Modernity.

Etymology

The word *Ai̯ri̯áh0 is influenced but not based on the Indo-Iranian ethnonym *Áryas "Aryan", as the root *h5ir "member/comrade" comes from Pangaean ʕihr "racial person".

History

Development from Paleolithic Codes

The story of Aryan starts with the transition from Atomism to Double Articulation, or from the Pangaean Code to Neolithic dialects (circa 12,000 BP). Noticeable is the influence of the Diluvian and Hyperborean Codes, which triggered several sound changes:

- Weak (plosive) stops become aspirated/murmured preceding a laryngeal consonant, as strong (ejective/implosive) stops gain plosive qualities in the same position.

| Weak Voiceless Stop before laryngeal |

Strong Voiceless Stop before laryngeal |

Weak Voiced Stop before laryngeal |

Strong Voiced Stop before laryngeal |

|---|---|---|---|

| /kH/→/kh/ | /kʼH/→/k/ | /gH/→/gɦ/ | /ɠH/→/g/ |

| /pH/→/ph/ | /pʼH/→/p/ | /bH/→/bɦ/ | /ɓH/→/b/ |

| /tH/→/th/ | /tʼH/→/t/ | /dH/→/dɦ/ | /ɗH/→/d/ |

- The production of aspirated/murmured series contaminates the regular sounds, whose qualities of WEAK and STRONG are rearranged to accomodate Aspiration/Breathy Voice instead of Ejection/Implosion.

| Weak Voiceless Stop | Weak Voiced Stop | Strong Voiceless Stop | Strong Voiced Stop |

|---|---|---|---|

| /k/→/k/ | /g/→/g/ | /kʼ/→/kh/ | /ɠ/→/gɦ/ |

| /p/→/p/ | /b/→/b/ | /pʼ/→/ph/ | /ɓ/→/bɦ/ |

| /t/→/t/ | /d/→/d/ | /tʼ/→/th/ | /ɗ/→/dɦ/ |

- Relative articulated sounds when stops transform into Diluvian consonant clusters following former examples of aspiration/breathy voice.

| Retracted before Laryngeal |

Retracted | Advanced before Laryngeal |

Advanced |

|---|---|---|---|

| /k̠H/→/khph/ | /k̠/→/kp/ | /k̟H/→/khth/ | /k̟/→/kt/ |

| /p̠H/→/phth/ | /p̠/→/pt/ | /p̟H/→/phkh/ | /p̟/→/pk/ |

| /t̠H/→/thkh/ | /t̠/→/tk/ | /t̟H/→/thph/ | /t̟/→/tp/ |

| /g̠H/→/gɦbɦ/ | /g̠/→/gb/ | /g̟H/→/gɦdɦ/ | /g̟/→/gd/ |

| /b̠H/→/bɦdɦ/ | /b̠/→/bd/ | /b̟H/→/bɦgɦ/ | /b̟/→/bg/ |

| /d̠H/→/dɦgɦ/ | /d̠/→/dg/ | /d̟H/→/dɦbɦ/ | /d̟/→/db/ |

| /k̠ʼH/→/kp/ | /k̠ʼ/→/khph/ | /k̟ʼH/→/kt/ | /k̟ʼ/→/khth/ |

| /p̠ʼH/→/pt/ | /p̠ʼ/→/phth/ | /p̟ʼH/→/pk/ | /p̟ʼ/→/phkh/ |

| /t̠ʼH/→/tk/ | /t̠ʼ/→/thkh/ | /t̟ʼH/→/tp/ | /t̟ʼ/→/thph/ |

| /ɠ̠H/→/gb/ | /ɠ̠/→/gɦbɦ/ | /ɠ̟H/→/gd/ | /ɠ̟/→/gɦdɦ/ |

| /ɓ̠H/→/bd/ | /ɓ̠/→/bɦdɦ/ | /ɓ̟H/→/bg/ | /ɓ̟/→/bɦgɦ/ |

| /ɗ̠H/→/dg/ | /ɗ̠/→/dɦgɦ/ | /ɗ̟H/→/db/ | /ɗ̟/→/dɦbɦ/ |

- Sonorants, contrary to the stop series, remain conserved when onset; however, they collapse as voiced codas.

| Voiceless Sonorant(I) |

Voiced Sonorant(I) |

Voiceless Sonorant(II) |

Voiced Sonorant(II) |

|---|---|---|---|

| /j̥/→/j̥/~/j/ | /j/→/j/ | /w̥/→/w̥/~/w/ | /w/→/w/ |

| /n̥/→/n̥/~/n/ | /n/→/n/ | /m̥/→/m̥/~/m/ | /m/→/m/ |

| /l̥/→/l̥/~/l/ | /l/→/l/ | /r̥/→/r̥/~/r/ | /r/→/r/ |

- The positive and negative forms of the sonorants still follow a Diluvian paradigm.

| Retracted Voiceless Sonorant |

Retracted Voiced Sonorant |

Advanced Voiceless Sonorant |

Advanced Voiced Sonorant |

|---|---|---|---|

| /j̠̊/→/j̥/~/j/ | /j̠/→/j/ | /j̟̊/→/j̥/~/j/ | /j̟/→/j/ |

| /n̠̊/→/kn/ | /n̠/→/kn | /n̟̊/→/pn/ | /n̊/→/pn/ |

| /l̠̊/→/l̥/~/l/ | /l̠/→/l/ | /l̟̊/→/l̥/~/l/ | /l̟/→/l/ |

| /ẘ̠/→/w̥/~/w/ | /w̠/→/w/ | /ẘ̟/→/w̥/~/w/ | /w̟/→/w/ |

| /m̠̊/→/dm/ | /m̠/→/dm/ | /m̟̊/→/gm/ | /m̟/→/gm/ |

| /r̠̊/→/r̥/~/r/ | /r̠/→/r/ | /r̟̊/→/r̥/~/r/ | /r̟/→/r/ |

- Within the turbulents, clicks are exchanged by plosive equivalents, and uvular laryngeals turn velar.

| Labiodental Click | Dental Click | Alveolar Click |

|---|---|---|

| /ʘ̪/→/dʷ/ | /ǀ/→/dʲ/ | /ǁ/→/t͡ɬ/ |

| Voiceless Uvular Laryngeal | Voiced Uvular Laryngeal |

|---|---|

| /χ/→/x/ | /ʁ/→/ɣ/ |

- Complex and long vowels are reduced to their basic and short versions.

| Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|

| /i/→/i/ | /ɨ/→/i/ | /u/→/u/ |

| /y/→/u/ | /ʉ/→/u/ | /ɯ/→/i/ |

| /e/→/e/ | /ɪ/→/e/ | /o/→/o/ |

| /ø/→/o/ | /ʊ/→/o/ | /ɤ/→/e/ |

| /e̞/→/i/ | /ə/→/ə/ | /o̞/→/u/ |

| /ɛ/→/e/ | /ɐ/→/a/ | /ɔ/→/o/ |

| /æ/→/e/ | /a/→/a/ | /ɒ/→/o/ |

| Special cases |

|---|

| HVHC > HVC |

| CHVHC > CVC |

| CHVH > CVH |

| /ʕɨ̀ː/→/əi̯/ |

| /V̰/→/Vː/~/aV/ |

| /V̤/ > /Vː/~/Va/ |

In Morphology, Aryan introduced a series of innovations by mixing and developing peculiarities from different Paleolithic Codes. The Hyperborean nominative -s for example was probably borrowed via another caucasian substrate, which completely assumed the role of epenthetic root (next to Aryan *-ar) in the construction "ROOT1 ROOT2". Primordial [ˈn̠ʕih ˈə] "old" would therefore yield *knīás "old" (=*knih1 *ás) [PIE *sénos "old"]. Furthermore, this development culminated into the Indo-European Ablaut. That is: when the accent falls into the epenthetic root, the first root suffers a phonetic change influenced by the interaction between laryngeals and vowels, which fuse into diphthongs or long vowels. This effect is considered a reflex of Umlaut in the Pangaean Code, where guttural fricatives can alternate between their vocalic equivalents and even modify the qualities of the nucleus.

| Stress in first root |

Stress in second root |

|---|---|

| HV́C-R | VVC-Ŕ |

| CV́C-R | C∅C-Ŕ |

| CV́H-R | CVV-Ŕ |

| Codex | Aryan | PIE |

|---|---|---|

| ˈhuhd-ə "water" | *h1úd-ar "water" | *wód-r̥ "water" |

| ˈhuhd ˈə "water-like" | *wid-rás "aquatic" | *ud-rós "aquatic" |

| ˈkhuħ-ə "sound" | *kʰúh2-as "sound" | *ḱléw-os "fame" |

| ˈkhuħ ˈə "sound-like" | *kʰaw-ás "sound-maker" | *ḱlu-ós "famous" |

Development into Indo-European Languages [...]

Some tendences include the aspirated velars of Aryan becoming the PIE palatal series (*Kʰ ⇒ *Ḱ); ....

https://en.wiktionary.org/w/index.php?title=Category:Proto-Indo-European_roots&from=A

- bʰeyh₂-

| Codex | Aryan | PIE | Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| k̠- | *kʰpʰ- | *ǵʰ-d | 1. *ǵʰewd- "to pour", *ǵʰed- "to defecate", *ḱh₂d- "to fall" |

| -k̠ | *-kp | *-kw | 1. *leykʷ- "to leave" |

| k- | *kʰ- | *ḱ | 1. *ḱe "this" |

| -k | |||

| k̟- | *kʰtʰ- | *ḱ-s | 1. *(s)ker-, *(s)kelH, *sek-, *ḱes-, *kh₂eyd- "to cut"; 3. *gleyH- "to stick", *bʰreyH- "to cut" |

| -k̟ | *-kt | *p-ḱ | 1. *peh₂ḱ- "to join", *peh₂ǵ- "to attach"; 2. *leyp- "to stick", *leyǵ- "to bind"; 3. *bʰendʰ- "to bind", *deh₁- "to bind" |

| g̠- | *gʰbʰ- | *gʰ-bʰ | 1. *(s)pregʰ- "sprinkle", *glewbʰ- "split", *bʰeh₂g- "to divide"; 3. *bʰeyd- "to split", *deh₂- "to divide" |

| -g̠ | -gb | *h₁éǵʰ "out" | |

| g- | |||

| -g | |||

| g̟- | *gʰdʰ- | *gʰ-dʰ | *gʰedʰ- "to join", *bʰendʰ- "to bind" |

| -g̟ | *-gd | *ǵ/∅ | ʕihg̟ ⇒ *h5igd- ⇒ *leǵ- "to gather" |

| k̠ʼ- | *kp- | *bʰ-g, *k-p | *bʰeg- "break", *bʰreg- "break", *bʰrew- "break", *bʰrews- "break", *kelh₂- "break", *(s)kep- "break", *Hrewp- "break" [may be from *Hrew- "tear out"] |

| -k̠ʼ | *-kʰpʰ | *w-ǵ | *lewǵ- ~ *weh₂ǵ- ~ *wreh₁ǵ- "to break" |

| kʼ- | |||

| -kʼ | |||

| k̟ʼ- | kt- | ||

| -k̟ʼ | -kʰtʰ | *ǵʰ/dʰ ~ *∅/dʰ | ʕihk̟ʼ ⇒ *h5ikʰtʰ- ⇒ *dʰerǵʰ- "to be firm" ~ *dʰer- "to support" |

| ɠ̠- | *gb- | *kʷ ~ *(s)k | ɠ̠ʕih ⇒ *gbih1- ⇒ *kʷelh1- "to turn around"; ɠ̠ʕihr ⇒ *gbair- > *(s)ker- "to bend" [semantic transition from "shrink/wither" to "bend/turn around"] |

| -ɠ̠ | |||

| ɠ- | |||

| -ɠ | |||

| ɠ̟- | *gd- | *gʰ/∅ ~ *ḱ/∅ | ɠ̟ʕih ⇒ *gdih1- ⇒ *gʰreh1- "to grow (plants)"; ɠ̟ʕihr ⇒ *gdair- ⇒ *ḱer- "to grow" |

| -ɠ̟ | *-gʰdʰ | *gʰ/dʰ | hohɠ̟ "growing fire" ⇒ *hogʰdʰ- ⇒ *dʰegʷʰ- "to burn" |

| p̠- | *pʰtʰ- | *bʰ/gʷ | *bʰegʷ- "flee", *bʰewg- "flee" |

| -p̠ | |||

| p- | *pʰ- | *bʰ- | *bʰer- "bear" |

| -p | |||

| p̟- | *pʰkʰ- | *bʰ/gʰ ~ *p/ḱ ~ *p/k | p̟ʕih ⇒ *pʰkʰih1- ⇒ *gʰabʰ- ~ *gʰeh₁bʰ- ~ *kap- "to seize", *peḱ- "to pluck" |

| -p̟ | |||

| b̠- | |||

| -b̠ | |||

| b- | |||

| -b | |||

| b̟- | |||

| -b̟ | |||

| p̠ʼ- | *pt- | ||

| -p̠ʼ | *-pʰtʰ | *bʰ-dʰ | *bʰedʰ- "dig" |

| pʼ- | *p- | *p | *per- "go through", *pel- "drive", *pent- "pass", *pes- "penis" |

| -pʼ | *-pʰ | *bʰ | *bʰerH- "pierce" |

| p̟ʼ- | |||

| -p̟ʼ | |||

| ɓ̠- | |||

| -ɓ̠ | |||

| ɓ- | |||

| -ɓ | |||

| ɓ̟- | *bʰ- | *bʰ | *bʰed- "improve" |

| -ɓ̟ | |||

| t̠- | |||

| -t̠ | |||

| t- | |||

| -t | |||

| t̟- | |||

| -t̟ | |||

| d̠- | |||

| -d̠ | |||

| d- | |||

| -d | |||

| d̟- | |||

| -d̟ | |||

| t̠ʼ- | |||

| -t̠ʼ | |||

| tʼ- | |||

| -tʼ | |||

| t̟ʼ- | |||

| -t̟ʼ | |||

| ɗ̠- | |||

| -ɗ̠ | |||

| ɗ- | |||

| -ɗ | |||

| ɗ̟- | |||

| -ɗ̟ | |||

| ʘ̠- | |||

| -ʘ̠ | |||

| ʘ- | *dʷ- | *bʰ- | *bʰed- "improve", *bʰil- "lovely" |

| -ʘ | |||

| ʘ̟- | |||

| -ʘ̟ | |||

| ǀ̠- | |||

| -ǀ̠ | |||

| ǀ- | |||

| -ǀ | *bʰeyh₂- "to shake" | ||

| ǀ̟- | |||

| -ǀ̟ | |||

| r- | 3. *bʰuH- "to be" | ||

| -r |

*bʰerǵʰ- "ascend"

- *bʰegʷ- "to flee" < *-pʰtʰ "to escape" < …

- *bʰerǵʰ- "to rise up " < *pk- "to eject" (?)

- *bʰil "good" < *dʷih1

*ǵʰes- "hand", *ǵʰey- "winter" (earlier lexical transition from "autumn", with similar use of English "fall"),

*gʷʰer- "warm" [from *gʰbʰōr- "glow"], *bʰeh₃g- "bake/roast" [from *gʰbʰor- "kindle"]

- temh1

kpih1 > bʰeg-; h5ikʰpʰ > weh2ǵ- ∅

r is added when the laryngeal is modified (h2 > h1)

l is added when the laryngeal is erased (h1 > ∅)

∅ (H) > r (H̥) > l (∅)

*bʰewdʰ “to be awake”

- *bʰeyd ~ *delh1 “to split”

- *deh2y- ~ *bʰeh2g- "to divide"

- *deh3 "to give"

‘’’D lemmas’’’

dewh1 (*deh3)

>

daim "to build" (*dem)

daik "to take" (*deḱ)

daipʰkʰ "to lead" (*dewk)

when two voiced consonants in a root, they becomes aspirated

In a root with a cluster, if there is no consonant as coda except:

-a laryngeal, the laryngeal is erased and the second element of the cluster becomes the coda.

- *gʰedʰ- (PIE) < ((*gʰed-)) < *gʰdʰih1- (Aryan) < g̟ʕih (Codex)

-a liquid, the liquid is incorporated and the first element of the cluster becomes the coda.

- *(s)pregʰ- ~ *sper- (PIE) < ((*bregʰ-)) < * gʰbʰair (Aryan) < g̠ʕihr (Codex)

exception: roots with longs vowels [dʰuh2- < pʰtʰūh1- (**pʰūt)]

h1egóM < aikṓm < aku ˈᴇːʔ > *ēh0 (Aryan) > *ih2 (PIE) uˈħihurk̟ʼ-a > *h2úrkʰtʰa > *h2ŕ̥tḱoes

- i and *u disappear before sonorants

mur, mrás > mer as PIE only accepts thorn clusters...

The language is demonstrared using two modern Indo-European languages (German and Russian) and two ancient ones (Latin and Greek).

mobile roots:

-*r "quality"

-*m "result"

-*dʰ "fixation"

NOTE: PIE neuter particle *-om derives from Aryan *(_)-am, which forms result nouns

origin of PIE declensions:

(_)-as Hysterokinetic:

- kʰúh2as > (*ḱléwos) > *ḱléwos

- kʰuh2ásyas > (*ḱlewésyos) > *ḱléwesos

(∅)-ás Hysterokinetic:

- pdás > *pád∅s (*pods) > *pṓds

- pdasyás > *padás∅s (*pedés) > *pedés

- (á)-as Acrostatic:

- pkáih1as > (*ǵʰéyos) > *ǵʰéyos

- pkáih1asyas > (*ǵʰéyosyos) > *ǵʰéyosyo

- (a)-ás Acrostatic:

- pkaisás > (*ǵʰoysós) > *ǵʰoysós

- pkaisásyas > (*ǵʰoysésyos) > *ǵʰoysósyo

ptár > ph2tḗr ptsaryás > ptryás (pətrés)> ph2trés

What marks a Transitional Dialect:

- the presence of mobile roots

p̠hṵh "fume" > *pʰtʰawimás (*pʰtʰūh1-*más) "smoke" > *dʰuh2mós (*dʰewh2-*mós)

- Hu, *u, *uH, *HuH > *we, *u, *ew, *we

Inheritances: huhg̠ > *h1ugp > *wegʷ ɦuhd > *h4ud > *sweyd

- ud > *úd

p̟ʼhuh > *pkuh > *ǵʰew pʼhuh > *puh > *plew Borrowings:

- h2ekʷ

-

- Hū, *ū, *ūH, *HūH> h2ew, ew, ewh2, h2ew

Inheritances: p̠hṵh > *pʰtʰawi > *dʰewh2 krhṳh > *GRuia > *krewh2 Borrowings: -phu- [Diluvian] > *po > *peh3 -

- Ho, o, oH, HoH > *h3e, e, *eh3, *Hew

Inheritances: kʼhohr > *kohr > *kerh3 (variant *ker from *kor) hoħd > *h1od > *h3ed ħoħd > *h2od > *h3ed ... > *poh2 > *peh3 (*puH) pʰol > bʰel "shine"

- h1oh1 > *h1ews

Borrowings: pohar [Diluvian] > *pawar (*paw-(a)-ar) > *péh2wr̥ (pew-r̥)

- h1engʷ < *h1ew-ǵenh1-yéti

-

- Hō, ō, ōH, HōH > *h3u, h3, *uh3, *Hu

Inheritances: Borrowings: -

- Ha, *a, *aH, *HaH > *h2e, *h2, *eh2, *h2e

Inheritances: phah > *pʰah > *bʰeh2 Borrowings: -

- ā > ...

Inheritances: Borrowings: -

- a > *e/o

Inheritances: ə > *(á)as > *(é)os Borrowings: -

- He, *e, *eH, HeH > *h1e, *h1, *eh1, *h1e

Inheritances: heħd > *h1ed > *h1ed Borrowings: -

- Hē, *ē, *ēH, HēH > ...

Inheritances: Borrowings: -

- Hi, i, iH, HiH > *ye, *i, *ey, *ye

Inheritances: Borrowings: -

- Hī, ī, īH, HīH > h1ey, ey, eyh1, h1ey

Inheritances: ʕii̯h > *ī > *h1ey Borrowings: +

- ew > eh3 [see: *gdew > deh3]

- aw > ew [see: kʰaw-ás > ḱlew]

+ h4- > s-

heħʘ̪ > h1eh2dʷ [nominative *séh2dʷ (=**h1éh2dʷ-as)] > *sweh2dʷ- > suavis there can only be one laryngeal in a root... except when former clicks.

*meh2dʷ (=**h1eh2dʷ-más) > *médʰu [*mélid, a variation]

dʷ- > *b-~bʰ-, -dʷ > -d dʲ- > *s~*sw-, -dʲ > -di

- h2oh2dʲ-, *h2óh2dʲam "hatred"

? > *ak "sharp" borrowing

- dʲairgʰ > *swergʰ... "be ill"

sour < *sūrós (*sweh2-rós) < *dʲāyrás (=*dʲeh2-rás)

h2isṓm/aísmi, h2isṓmas/aísmas > *h1ésmi, *h1smós h2isḗs/aíssi, h2isḗtas/aístas > *h1ési, *h1sté (*h1stés 2P.DUAL) h2isī́t/aísti, h2isī́nt/aísant> *h1ésti, *h1sénti

- /ə/ > */e/ when pretonic or tonic polysyllabic [exception: o-derivation]

- /ə/ > */o/ when postonic or tonic monosyllabic (*pʰ∅rás > *pʰárs >*pʰórs > *pʰṓr) [exception: o-derivation] *monosyllabic words without pithc accept /e/ instead (*swa > *swe)

- /əi̯/ > */e/, */aː/ when result of zero-grade (*gain- >*g∅n-tás > *gnaitás > *gnātós, as in Latin gnātus and Greek -γνητός)

- /ai̯/ > */ai̯/

- kʰpʰ-

- kp- > *kʷʰ-

- kn- > *sn-

- h2i (TD) > *h1e (PIE)

an original click as onset inverts the laryngeals: ǁheħp > tɬeh1p> seh1p an original click as coda preserves both laryngeals: heħʘ̪ > *h1eh2dʷ > sweh2d həħǁ > *h1ah2t͡ɬ > *sent

When an <e> is introduced in adjectives, the accent falls n̠ʕih > *knaiás > *sénos "old" compare

- sādú > *swādús "sweet"

- sādú méh2dʷ

- swādús médʰu~mélid

Primordial elements transitioned into particles in Aryan. That is: Aryan roots could be changed back then. Those were the mobile roots. For example: *dʷ survived as PIE *-id, which was a particle used to indicate comestibles.

- pʰrás

laryngeals turn into vowels and vice-versa

- mai > *meh1

?we are searching for a single voiceless plosive before a voiced one? ?"Aryan doesn't accept initial voiced clusters of original implosives? As if **dbíoh1 > *díopʰ "?

h1uC ~ h1oC > uj ~ oj h1aC ~ h1əC > aj ~ i h1iC ~ h1eC > ī ~ ej Cuh1 ~ Coh1 > uj ~ oj Cah1 ~ Cəh1 > aj ~ i Cih1 ~ Ceh1 > ī ~ ej - h2uC ~ h2oC > aw ~ ow h2aC ~ h2əC > ā ~ i h2iC ~ h2eC > aj ~ ej Cuh2 ~ Coh2 > aw ~ ow Cah2 ~ Cəh2 > ā ~ i Cih2 ~ Ceh2 > aj ~ ej - h3uC ~ h3oC > ū ~ ow h3aC ~ h3əC > wa ~ u h3iC ~ h3eC > ī ~ je Cuh3 ~ Coh3 > ū~ ow Cah3 ~ Cəh3 > wa ~ u Cih3 ~ Ceh3 > iw ~ ew

| Sanskrit | Avestan | O.C.S. | Lithuanian | Albanian | Armenian | Hittite | Tocharian | Greek | Latin | Goidelic | Gothic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >*p | p; pʰ | p; f | p | p | p | h; w | p; pp | p | p / pt | p | ∅ | f; β |

| >*t | x x | |||||||||||

| >*k | x x | |||||||||||

| >*ḱ | x x |

p pt p ∅ f; b [β] [C 6] f; v, f[C 2]

thorn clusters, *sD, *sR, ? *ts, ? Bartholomae's law...

| PIE | Indo-Iranian | Balto-Slavic | Alb. | Arm. | Anatol. | Toch. | Greek | Italic | Celtic | Germanic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanskrit | Avestan | O.C.S. | Lith. | Hitt. | Latin | Old Irish | Gothic | English | |||||||

| normal | C+[j] [C 1] | normal | -C- [C 2] [C 1] | ||||||||||||

| *p | p; ph [pʰ] [C 3] | p; f [C 4] | p | h; w [C 5] |

p, pp | p | pt | p | ∅ | f; b [β] [C 6] |

f; v, f[C 2] | ||||

| *t | t; th [t̪ʰ] [C 3] | t; θ[C 4] | t | tʿ [tʰ] | t, tt; z [ts] [C 7] |

t; c [c] [C 7] |

t | s; tt/ss[C 5] | t | t | th [θ] | þ [θ]; d [ð]; [C 6] |

th; d; [C 6] | ||

| *ḱ | ś [ɕ] | s | š [ʃ] | th [θ]; k[C 8] |

s | k, kk | k; ś [ɕ][C 8] |

k | c [k] | c [k] | ch [x] | h; g [ɣ] [C 6] |

h; ∅;[C 2] y [C 6] | ||

| *k | k; c [t͡ɕ]; [C 7] kh [kʰ] [C 3] |

k; c [tʃ]; [C 7] x[C 4] |

k; č [tʃ]; [C 7] c [ts][C 9] |

k | k; q [c][C 9] |

kʿ [kʰ] | |||||||||

| *kʷ | k; s; [C 7] q [c][C 9] |

ku, kku | p; t; [C 7] k[C 10] |

qu [kʷ]; c [k] [C 11] |

ƕ [ʍ]; gw, w [C 6] |

wh; w [C 6] | |||||||||

| *b | b; bh [C 3] | b; β [C 12] | b | p | b | pt | b | b [b] | -[β]- | p | |||||