Lifashian: Difference between revisions

m →Verbs |

|||

| Line 418: | Line 418: | ||

The past augment is '''e''' if the root vowel (or first vowel of the root) is a front vowel (e.g. ''berámi'' "I carry", ''eberam'' "I carried"), '''a''' otherwise. | The past augment is '''e''' if the root vowel (or first vowel of the root) is a front vowel (e.g. ''berámi'' "I carry", ''eberam'' "I carried"), '''a''' otherwise. | ||

====Nasal infix verbs==== | ====Nasal infix verbs==== | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ '''''pinesmi'' (√pisy-) "I mark"''' | |+ '''''pinesmi'' (√pisy-) "I mark"''' | ||

| Line 443: | Line 442: | ||

|} | |} | ||

Note that the second person singular present ends in '''-si'''; in the example, it is ''-syi'' due to assimilation to the previous consonant. | Note that the second person singular present ends in '''-si'''; in the example, it is ''-syi'' due to assimilation to the previous consonant. | ||

====Copula==== | ====Copula==== | ||

The first conjugation in Lifashian is the most common, the one with the most regularized verbal formations, and (by means of the suffix ''-iy-'') the main productive one. Nearly all verbs ending in ''-ámi'' in the first person singular of the present (the citation form) belong to it. | The first conjugation in Lifashian is the most common, the one with the most regularized verbal formations, and (by means of the suffix ''-iy-'') the main productive one. Nearly all verbs ending in ''-ámi'' in the first person singular of the present (the citation form) belong to it. | ||

Revision as of 19:25, 19 March 2020

| Lifashian | |

|---|---|

| sá lommá lífasyása | |

| Pronunciation | [[sɑː ˈlɔŋnɑː ˈliːfæʃɑːsæ]] |

| Created by | Lili21 |

| Date | Apr 2019 |

| Setting | Alt-Earth |

| Ethnicity | Lifashians (lífasyi) |

| Native speakers | 6,200,000 (2016) |

Indo-European

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Dár Lífasyám |

| Regulated by | National Lifashian Language Board so Majalis Lommehi Dáré Lífasyám |

Lifashian, natively referred to as (at) lífasyátat or (sá) lommá lífasyása, is an Indo-European language, an isolate inside the family, spoken in an alternate timeline of Earth[1] in the northeastern corner of Asia Minor, i.e. the historical region of Pontus and neighboring areas across the Pontic Alps into the Armenian highlands. It is the official language of the former Soviet republic of Dár Lífasyám, spoken by the majority of its population.

Lifashian developed on its own, distinctly from other Indo-European languages, despite sharing some traits with the Anatolian languages, Armenian, and Greek. Its vocabulary has a substantial number of inherited roots, but through millennia the language absorbed many loanwords, especially from Persian and Arabic (through the former), and to smaller extents from its neighbours Armenian, the Kartvelian languages and Turkish, as well as from Greek and Russian.

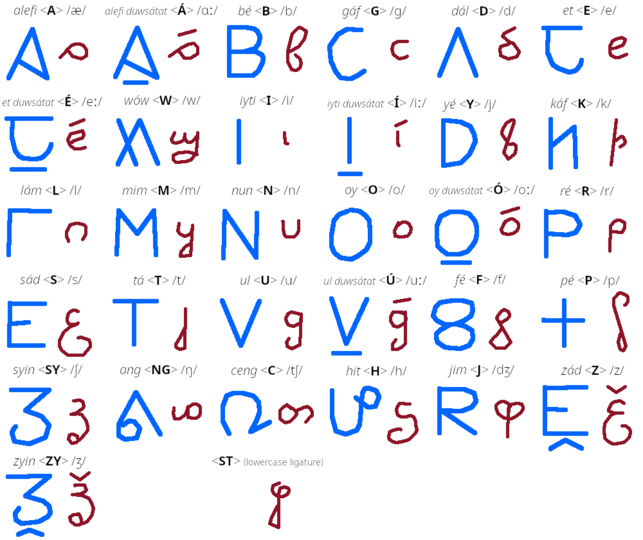

It is written in the Lifashian alphabet, a bicameral script ultimately related to other ancient scripts of Asia Minor like the Lydian alphabet.

In external history and setting, Lifashian is meant to be a more serious reboot of Wendlandish, though belonging to a different IE branch and being located in another area of Eurasia.

Orthography

Lifashian has been written since ancient times in its own alphabet; initially a derivative of other ancient scripts of Asia Minor (possibly from the Lydian alphabet, which it shares most of the alphabetical order with), it later further modified the ancient letters, which became the modern majuscules, and developed its own set of minuscule letters, which are today most often very different from the majuscules. Cursive minuscules (not in the table below) are furthermore often quite different from both sets.

The common sequence /ŋn/ is written as mm.

Phonology

Consonants

The consonants of modern and literary Lifashian are the following ones:

| → PoA ↓ Manner |

Labial and Labiodental |

Alveolar | Palatal and Alveolo-Palatal |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Plosives | Voiceless | p | t | k | (q) | (Ɂ) | |

| Voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||

| Affricates | Voiceless | tʃ | |||||

| Voiced | dʒ | ||||||

| Fricatives | Voiceless | f | s | ʃ | (x) | h | |

| Voiced | z | ʒ | (ɣ) | ||||

| Laterals | l | ||||||

| Trill | ɹ | ||||||

| Approximants | w | j | |||||

The phonemes /q Ɂ x ɣ/ only occur in Perso-Arabic words, but except for careful formal speech most speakers merge the former with /k/, do not pronounce /Ɂ/, and merge the latter two with /h/. The main minority of Dár Lífasyám, Laz speakers, are prone to using them more except for the glottal stop.

The consonants /z ʒ/ were also introduced from Persian and do not appear in native words, but also due to their prominence in Russian loans they are distinguished by virtually every speaker.

Vowels

Modern standard Lifashian has a ten-vowel system with five phonemes whose main distinction is of length, and length and quality for low vowels.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i iː | u uː |

| Mid | e eː | o oː |

| Low | æ | ɑː |

In the speech of young urban Lifashians there is a noticeable ongoing sound change in the high vowels, where the vowels are being restructured with long ones being front and short ones being back, and then distinguishing them for roundedness. Therefore, the high vowels of those speakers ae [iː yː ɯ u], result of the [i] → [ɯ] and [uː] → [yː] shifts.

Hamza

Peculiar of Lifashian vowels is hamzá (/ˈhæŋzɑː/, also written as hangzá according to pronunciation), a phenomenon referred to with the Arabic word for a similar-sounding but unrelated phoneme. Lifashian hamzá is in fact closer to Danish stød or the Latvian broken tone, and its origins reach back to Proto-Indo-European, reflecting an original *h₁ in some positions. Hamza is not represented orthographically.

Hamza may occur on any vowel, either long or short, as long as it is stressed (either primarily or in compounds). Hamza on short vowels is always realized as creaky voice or pharyngealization, while hamza on long vowels, for many speakers, is phonetically closer to a broken tone, with a full glottal stop interrupting the sound, before a short echo of the vowel:

- elemi "I eat" /ˈeˤlemi/ [ˈeˤlemi]

- élom "I ate" /ˈeːˤlom/ [ˈeɁĕlom]

- lúlasyam "twelve" (masc.) /ˌluːˤˈlæʃæm/ [ˌluɁŭˈlæʃæm]

Minimal pairs distinguished by hamza include the forms of some verbs whose root has hamza and the non-singular endings were originally stressed on an ending that absorbed the root vowel, such as mulúti /muˈluːˤti/ "he/she/it speaks" vs. mulúti /muˈluːti/ "they speak".

Morphology

Nouns

Lifashian nouns distinguish two numbers (hamári, sg. hamár) – singular (enikás) and plural (pilifuntikás) – and four cases (pitósi, sg. and pl.) – nominative (lónamsyás or in older literature onomastikás), genitive (gyenikás), dative (dotikás), and accusative (eytiatikás).

Nouns can belong to three different genders (jensi, sg. jens): masculine (bátursyás), feminine (ninfasyás), or neuter (udeterás).

Nouns can be categorized as following one of six different declensions (kilisi, sg. and pl.); in most cases, each declension only contains nouns of a single gender.

1st declension (masculine)

The first declension (kilisi piristómás) of Lifashian contains most masculine nouns, inherited or borrowed. The nominative singular, citation form, ends in -as, -s, -sy, or has no ending.

|

|

|

|

2nd declension (feminine)

The second declension (kilisi spétás) contains most feminine nouns. Their citation form always ends in -á.

|

|

3rd declension (neuter)

The third declension (kilisi tírisyás) contains nearly all neuter nouns, and its forms in the genitive and dative are identical to the first declension. Its citation form ends in -am for all native words and some borrowings, or in a vowel plus -n in other borrowings. Such -n was often part of the stem in the donor language, but has been treated as an inflection in Lifashian.

|

|

4th declension (masculine, feminine)

Words of the fourth declension (kilisi pitórisyás) are either masculine or feminine. Their citation form ends in -é.

|

|

5th declension (neuter)

The fifth declension (kilisi pembisyás), mostly unproductive, contains neuter nouns whose lemma forms end in -é. They are clearly distinct from 4th declension ones.

|

6th declension (masculine)

Words of the sixth declension (kilisi syússyás) are predominantly masculine, ending in -i in their citation form; its plural forms are the same as in the first declension. Some borrowings are also included in this declension.

|

|

Verbs

Regular verbs

The first conjugation in Lifashian is the most common, the one with the most regularized verbal formations, and (by means of the suffix -iy-) the main productive one. Nearly all verbs ending in -ámi in the first person singular of the present (the citation form) belong to it.

| Present | Past | |

|---|---|---|

| 1SG | syúpámi | asyúpam |

| 2SG | syúpesi | asyúpes |

| 3SG | syúpeti | asyúpet |

| 1PL | syúpamas | asyúpame |

| 2PL | syúpete | asyúpete |

| 3PL | syúpáti | asyúpát |

The past augment is e if the root vowel (or first vowel of the root) is a front vowel (e.g. berámi "I carry", eberam "I carried"), a otherwise.

Nasal infix verbs

| Present | Past | |

|---|---|---|

| 1SG | pinesmi | epísyam |

| 2SG | pinessyi | epísyes |

| 3SG | pinesti | epísyet |

| 1PL | pinsmas | epísyame |

| 2PL | pinste | epísyete |

| 3PL | pinsyéti | epísyát |

Note that the second person singular present ends in -si; in the example, it is -syi due to assimilation to the previous consonant.

Copula

The first conjugation in Lifashian is the most common, the one with the most regularized verbal formations, and (by means of the suffix -iy-) the main productive one. Nearly all verbs ending in -ámi in the first person singular of the present (the citation form) belong to it.

| Present | Past | |

|---|---|---|

| 1SG | esyim | astám |

| 2SG | esyi | astás |

| 3SG | esti | astát |

| 1PL | somé | astame |

| 2PL | ste | astate |

| 3PL | séti | astát |

Syntax

Vocabulary

Texts

Schleicher's Fable (So masy aw tí esyúi)

- Nyé masy, pesy hawláná ne astát, elerset esyúás; nyé nyam arabam karetántám etenget, nyé nyim tangtom duwsátam eberet, nyé lengom nyim báturom eberet.

- So masy tós esyúwi amulút: «Mintat syardém duwsom résy mewi puréti, pimbe báturom, esyúám lúkétom, wilémi.»

- Tí esyúi tási masyí amulút: «Hú, a masy! Mintá syardéa duwsom résy ósmi puréti, pimbe histom wilémas: nyé bátur, so kirius, et tosy masyé hawlánam eynemeti. Dán méat hawlánehi ha tosy masyé esti.»

- Histom ahút, so masy gacewam ham at peliné etinemat.

- [ɲeː mæʃ peʃ hæu̯ˈlɑˤːnɑː ne æʃˈtɑːt eˈlerʃet eˈʃuː.ɑːs . ɲeː ɲæm ˈæræbæm kæreˈtɑːntɑːm eˈteŋet . ɲeː ɲim ˈtæŋtom duu̯ˈsɑːtæm eˈberet . ɲeː ˈleˤŋom ɲim ˈbɑːturom eˈberet]

- [so ˈmæʃ toːs eˈʃuːwi amuˈluːˤt . minˈtæt ʃærˈdeːm duu̯som ˈreːʃ mewi puˈreːti . ˈpimbe ˈbɑːturom . eˈʃuːɑːm luːˈkeːtom . wiˈleːmi]

- [tiː eˈʃuː.i tɑːsi ˈmæʃiː amuˈluːt . huː æ ˈmæʃ . minˈtɑː ʃærˈdeː.æ duu̯som ˈreːʃ oːsmi puˈreːti . ˈpimbe ˈhistom wiˈleːmæs . ɲeː ˈbɑːtur . so ˈkirjus . et toʃ ˈmæʃeː hæu̯ˈlɑˤːnæm ei̯ˈnemeti . dɑˈn ˈmeː.æt hæu̯ˈlɑˤːnehi hæ toʃ ˈmæʃeː eʃˈti]

- [ˈhistom aˈhuːt so ˈmæʃ ɡaˈtʃewæm hæm at ˈpelineː etiˈnemæt]