Lifashian

| Lifashian | |

|---|---|

| sá gulká lífasyása | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [[sɑː ˈguɬkɑː ˈliːfæʃɑːsæ]] |

| Created by | Lili21 |

| Date | Apr 2019 |

| Setting | Alt-Earth |

| Ethnicity | Lifashians (lífasyi) |

| Native speakers | 5,000,000 (2021) |

Indo-European

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Dár Lífasyám |

| Regulated by | National Lifashian Language Board so Majalis Gulkáhs Dárahs Lífasyám |

Lifashian, natively referred to as (at) lífasyátat or (sá) gulká lífasyása, is an Indo-European language, an isolate inside the family, spoken in an alternate timeline of Earth in the northeastern corner of Asia Minor, i.e. the historical region of Pontus and neighboring areas across the Pontic Alps into the Armenian highlands. It is the official language of the former Soviet republic of Dár Lífasyám, spoken by the majority of its population. Lifashian is the native language of about five million people in the world, the majority of which in Dár Lífasyám and neighboring areas in Eastern Turkey; a small Lifashian diaspora is found mostly in Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan, as well as in some Western European countries.

Lifashian developed on its own, distinctly from other Indo-European languages, although it is definitely closer to the Anatolian languages, particularly the Luwian subgroup, than to other languages in the family, despite sharing some traits with Armenian and Greek. Its vocabulary has a substantial number of inherited roots, but through millennia the language absorbed many loanwords, especially from Persian and Arabic (through the former), and to smaller extents from its neighbours Armenian, the Kartvelian languages and Turkish, as well as from Greek and Russian. Long-term Genoese colonization and reciprocal contacts also introduced many Ligurian loans, as well as forming one of the main ethnic minorities in the country, Lifashian Ligurians, which had a marked influence on the culture of coastal urban areas.

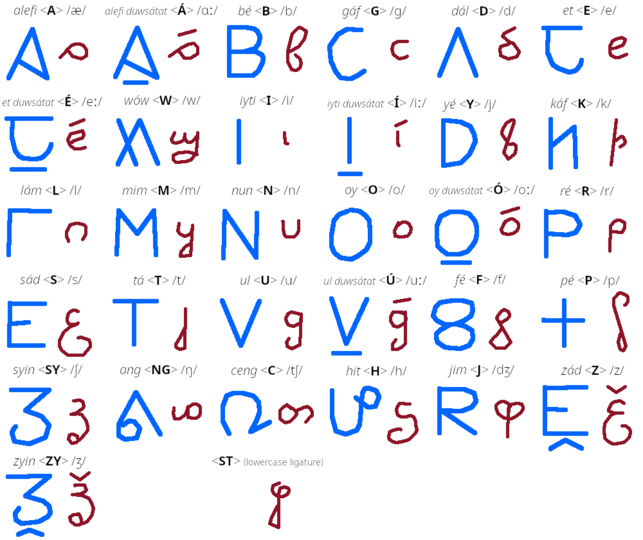

It is written in the Lifashian alphabet, a bicameral script ultimately related to other ancient scripts of Asia Minor like the Lydian alphabet.

Orthography

Lifashian has been written since ancient times in its own alphabet; initially a derivative of other ancient scripts of Asia Minor (possibly from the Lydian alphabet, which it shares most of the alphabetical order with), it later further modified the ancient letters, which became the modern majuscules, and developed its own set of minuscule letters, which are today most often very different from the majuscules. Cursive minuscules (not in the table below) are furthermore often quite different from both sets.

The common sequence /ŋn/ is written as mm.

Letter names are acrophonic (except for ang for ng, which cannot start a word[1]), and mostly taken from the Persian names of Arabic letters, although a few names are earlier and correspond to Syriac names (most notably syin for sy). The names for vowels except alefi (or non-acrophonic elefi, which is the form used in the word for "alphabet", elefibáté) are likely Lifashian inventions, but with a Greek influence in et (e) and iyti (i), as well as in using duwsátat (big) for the names of long vowels. Lifashian inventions are also ang (ng) and the following letter ceng (c).

All letter names are neuter even if they are all first declension nouns (sixth in the case of alefi and iyti).

Phonology

Consonants

Standard Lifashian - which is based on a polished, late 19th century register of the Trapezuntine dialect - has the following 21 consonants. The consonant inventory itself is close to the ones of many European languages, as well as quite similar to neighboring Turkish.

| → PoA ↓ Manner |

Labial and Labiodental |

Alveolar | Palatal and Alveolo-Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosives | Voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| Voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||

| Affricates | Voiceless | tʃ | ||||

| Voiced | dʒ | |||||

| Fricatives | Voiceless | f | s | ʃ | h | |

| Voiced | z | ʒ | ||||

| Laterals | l | |||||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Approximants | w | j | ||||

In contemporary Lifashian all 21 consonants are considered to be native, but etymologically the phonemes /z ʒ/ are found only in loans from New Persian and Arabic through Persian (starting from ca. the 9th century CE), Ligurian (starting from the 12th century), or later and less prominent sources.

The [ɲ] phone is sometimes considered to be a phoneme, and is recognized as a distinct sound by speakers, but it is phonemically analyzed as /nj/. While any underlying /sj/ is also realized as [ʃ], the latter is not just a phone but a phoneme, as it occurs in environments where an underlying /sj/ would be impossible: /ʃ/ is a common coda, but /j/ cannot occur in a coda after another consonant.

Old Lifashian used to have a /ð/ phoneme which was inconsistently written as d or l in the early stages of Lifashian writing (around the 7th century), but already by the beginning of the 9th century all words that were written with alternating d or l are consistently written with l. Lifashian /ð/ in fact merged with /l/ unless before consonants (or after n), where it merged with /d/; this is easily noticed from the fact that [ð] from multiple loanword sources before the spread of Islam is reflected as /l/: see for example Greek given names such as Δηϊδάμεια > Lilamiyá or Θουκυδίδης > Fókílil (but Δρυάδα > Driálá[2] for a preconsonantal example) or general nouns such as δελφῖνος > lalfín and στάδιον > sitálam. Later in Lifashian history, foreign [ð] is borrowed as /d/, or indirectly as /z/ from Arabic through Persian; see for example δημοκρατία > dimokratíyá.

Vowels

Modern standard Lifashian has a ten-vowel system with five phonemes whose main distinction is of length, and length and quality for low vowels.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i iː | u uː |

| Mid | e eː | o oː |

| Low | æ | ɑː |

In the speech of young urban Lifashians there is a noticeable ongoing sound change in the high vowels, where the vowels are being restructured with long ones being front and short ones being back, and then distinguishing them for roundedness. Therefore, the high vowels of those speakers ae [iː yː ɯ u], result of the [i] → [ɯ] and [uː] → [yː] shifts.

Hamza

Peculiar of Lifashian vowels is hamzá (/ˈhæŋzɑː/, also written as hangzá according to pronunciation), a phenomenon referred to with the Arabic word for a similar-sounding but unrelated phoneme. Lifashian hamzá is in fact closer to Danish stød or the Latvian broken tone, and its origins reach back to Proto-Indo-European, reflecting an original *h₁ in some positions. Hamza is not represented orthographically.

Hamza may occur on any vowel, either long or short, as long as it is stressed (either primarily or in compounds)[3]. Hamza on short vowels is always realized as creaky voice or pharyngealization, while hamza on long vowels, for many speakers, is phonetically closer to a broken tone, with a full glottal stop interrupting the sound, before a short echo of the vowel:

- elemi "I eat" /ˈeˤlemi/ [ˈeˤlemi]

- élaha "I ate" /ˈeːˤlæhæ/ [ˈeɁĕlæhæ]

- lúlasyam "twelve" (masc.) /ˌluːˤˈlæʃæm/ [ˌluɁŭˈlæʃæm]

Minimal pairs distinguished by hamza include the forms of some verbs whose root has hamza and the non-singular endings were originally stressed on an ending that absorbed the root vowel, such as mulúti /muˈluːˤti/ "he/she/it speaks" vs. mulúti /muˈluːti/ "they speak". A lexical minimal pair, possibly the first one explained to Lifashian students, is lú /luːˤ/ "two (masc.)" (from PIE *dwoh1) and lú /luː/ "hill" (probably from Akkadian dû, itself from Sumerian).

Historical phonology

Lifashian is peculiar due to its phonological development, as among Indo-European languages it preserves laryngeals as consonants in many environments. *h₂ is frequently preserved as /h/, or - in original codas - by lengthening and colouring a preceding vowel; *h₃ is usually reflected as /f/, or - in niche cases - as /w/ or /ɡ/. *h₁, meanwhile, is the least accurately preserved of the three laryngeals, usually as hamza (although there are some cases of hamza from other laryngeals, mostly due to dissimilation). Some examples:

- PIE *h₁esh₂ṛ-om > ehorm /ˈeˤhorm/ "blood"

- PIE *h₂éwis > hawis /ˈhæwis/ "bird"

- PIE *wḷg-k-eh₂ > gulká /ˈgulkɑː/ "tongue; language", cfr. the non-coda laryngeal in the plural form *wḷg-k-eh₂es > gulkehes /ˈgulkehes/

- PIE *h₃eḱtōw > fastú /fæʃˈtuː/ "eight"

- PIE *h₃ésth₁-om > festam /ˈfeˤʃtæm "bone"

- PIE *déh₃-ts > left /left/ "gift"

- PIE *h₃dónts > gelont /ˈgelont/ "tooth" through intermediate *(h)w(ǝ)dónt-.

The /f/ realization for the reflex of *h₃ is a later development in most dialects; however, dialects in the Bádwer province still have a different /χ/ phoneme - /leχt/ for standard /left/, /eχˈront/ for standard /ˈgelont/ - as do the dialects from the western part of Mengikás province, which have /xʷ/ (or /ʍ/ in some areas) instead, cf. /xʷǝˈlont/, /ˈxʷasto/ "eight", /ˈxʷeˤstɐm/ "bone".

Morphology

Nouns

Lifashian nouns distinguish two numbers (hamári, sg. hamár) – singular (enikás) and plural (pilifuntikás) – and four cases (pitósi, sg. and pl.) – nominative (lónamsyás or in older literature onomastikás), genitive (gyenikás), dative (dotikás), and accusative (eytiatikás).

Of these cases, the genitive is only found in the plural and in a few singular nominals, but not in nouns themselves. The PIE genitive singular has been replaced in nouns, by a form called the possessive, which is an adjective with nominal declension; Lifashian shares this feature with the Luwian group and Lydian.

Nouns can belong to three different genders (jensi, sg. jens), as in most IE languages, but not Anatolian ones: masculine (turéssyás), feminine (ninfasyás), or neuter (udeterás).

Nouns can be categorized as following one of six different declensions (kilisi, sg. and pl.); in most cases, each declension (except the fourth) only contains nouns of a single gender.

All declensions are productive, although the majority of contemporary loanwords is assigned to one of the first three. Historically, the termination (and not the noun class) of the original word determines the declension, with original -e words being mostly assigned to the neuter fifth declension unless explicitely animate (mostly given names or nouns referring to humans borrowed from Ligurian), in which case they are either masculine or feminine fourth declension nouns. Words ending in a back rounded vowel or in a voiced stop in the donor language in most cases end in -i and are sixth declension nouns; this is again mostly noticeable in the plethora of Ligurian loans (such as e.g. Lig. mandillo [mãˈdilu] borrowed as mangdili [mæŋˈdili] "handkerchief").

Words which ended in voiced stops or sonorants in the donor language typically also show an -i (and are therefore sixth declension nouns) in Lifashian, but this is not the case for most such words borrowed in the last century (as e.g. jáz "jazz").

Nearly every noun, whether native or borrowed, is declined according to one of the six declensions; however, transcriptions of foreign anthroponyms and toponyms are indeclinable whenever they do not end in one of the typical endings of the declensions. See e.g. toponyms such as Peru "Peru", Konggo "Congo", or Wanwátu "Vanuatu".

While the declensions are generally tied to grammatical gender, this is sometimes overridden by natural gender. Most notably, the agent noun-forming suffixes -éc and -tél are epicene and form first declension nouns that can take either masculine or feminine concord (articles and adjectives) depending on the actual referent; many nouns which refer to humans obey such rules no matter which declension they belong to (as e.g. hulamá "scientist"). In some cases, neuter gender is an option too, as with nesfertél, traditionally either masculine or feminine for "messenger", nowadays frequently used as a neuter noun with the meaning of "messenger, chat program", a calque from English[4].First declension neuters also include nouns in -pít-tél, which are often calques of Greek nouns in -λόγιον, such as syahtapíttél (clock) and hámorpíttél (calendar).

Other nouns that denote people, especially if borrowed, are also epicene nouns, such as hartís (citizen (the ending only is borrowed)), kosmonawt (astronaut), pangk (punk), syahír (poet); in some dialects, inherited helbart (child) is used as epicene too (but the standard has the feminine form helbartá). A select number of inherited nouns do not refer to people but have a different grammatical gender than the one of its declension, most notably napat (night) and the plurale tantum haréni (mind), which are feminine first declension nouns.

1st declension (masculine)

The first declension (kilisi hancás) of Lifashian contains most masculine nouns, inherited or borrowed. The nominative singular, citation form, ends in -as, -s, -sy, or has no ending.

In all following tables, the hyphen in the possessive form marks the place for the inflectional endings. In the nominative, the possessive forms are e.g. mísyahs (masculine), mísyaha (feminine), mísyaham (neuter).

|

|

|

Note that a very small number of borrowings may end in vowels and be declined according to this declension when they refer to male humans or animals, such as e.g. pasyá "governor" (from Ottoman Turkish), whose gen.sg. is pasyáé, dat.sg. pasyáí and so on. This is true for -á nouns when this vowel is also stressed; otherwise, they take the appropriate gender concord but are declined as second declension nouns.

2nd declension (feminine)

The second declension (kilisi sfétás) contains most feminine nouns. Their citation form always ends in -á.

|

|

3rd declension (neuter)

The third declension (kilisi tartás) contains nearly all neuter nouns, and its forms in the genitive and dative are identical to the first declension. Its citation form ends in -am for all native words and some borrowings, or in a vowel plus -n in other borrowings. Such -n was often part of the stem in the donor language, but has been treated as an inflection in Lifashian.

|

|

4th declension (masculine, feminine)

Words of the fourth declension (kilisi pitúrtás) are either masculine or feminine. Their citation form ends in -é.

|

|

5th declension (neuter)

The fifth declension (kilisi penftás), mostly unproductive (although the common derivational suffix -né, marking collective nouns, belongs to this declension), contains neuter nouns whose lemma forms end in -é. They are clearly distinct from 4th declension ones.

|

6th declension (masculine)

Words of the sixth declension (kilisi géstás) are predominantly masculine, ending in -i in their citation form; its plural forms are the same as in the first declension. Some borrowings are also included in this declension.

|

|

Articles

The articles follow their own particular declension. Note that masculine and neuter articles have the same forms in the genitive and dative.

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |

| Nominative | so | at | sá | tí | tá | tás |

| Genitive | — | tyám | tásam | |||

| Dative | tási | tasyé | tós | tábi | ||

| Accusative | tom | at | tám | tás | tá | tás |

Usage of the article

The definite article is generally used in most cases, a lot more when compared to English.

Personal names are not used with articles in the standard language, but it is a prominent feature of Western dialects (in the provinces of Elenasyahr and Kawéy, and parts of Milesyihars province, as well as in the (mostly extinct) dialects of the Sinope area), which have greater Greek influence and use articles in front of names anywhere except for vocative phrases; e.g. tási Syáhpúrí tom námirom eléha. "I gave Syáhpúr the book."

However, even in the standard language, an article is used in front of pluralized given names to denote a group of more people defined from one of them, often (depending on context) "X and their family", e.g. tás Freyánehes "Freyáná and her family/friends/colleagues/etc."

Another structure that has a parallel formation in Greek, the genitive interposed between the article and noun, is found to this day in official, formal written Lifashian, as well as in certain speech forms (fixed phrases or official speeches such as Presidential speeches or court verdicts); e.g. at tyám Lífasyám mulúman (Parliament of the Lifashians).

Titles (adpositions) follow the proper names they refer to and are not used with any article (e.g. Iyústinyanos iluhan rómeyás "Roman Emperor Justinian (I)"), unless they include an adjective not part of the title itself, in which case this usually precedes the noun (e.g. Nikoláy 2. so ejesiyás iluhan russyás "Nicholas II, the last Tsar of Russia").

Titles however regularly use possessives or other determinatives (e.g. Syáhpúr barté minso "my brother Syáhpúr").

As for placenames:

- All names of countries and territories require the definite article, except for those constructed as Dár + genitive of an ethnonym[5], or Persianized placenames ending in -(V)stán, which are never accompanied by articles.

Originally collective (fifth declension) toponyms do not use articles in the standard, but they are sometimes used in more colloquial registers, e.g. (at) Midihafnené (Mesopotamia), (at) Selné Syené (Côte d'Ivoire). - Cities do not require an article unless it is part of their name, except when using adjectives. Placenames which are pluralia tantum, especially of Greek origin, generally always require an article (e.g. tás Afénehes "Athens", tás Sirákusehes "Syracuse").

Non-nativized foreign placenames which include an article do not substitute it with the Lifashian one, see e.g. u-Portu "Porto", Andóra-la-Welyá "Andorra la Vella", l-Ákwilá "L'Aquila", but cf. nativized sá Ispézá "La Spezia". Most Arabic placenames, however, are nativized without the article, e.g. Káhirá "Cairo". - Hydronyms always use articles, e.g. so Úruti (Euphrates).

Possessives

Pronominal possessives follow the same declension of articles, as they are diachronically formed from the pronominal genitive attached to an article; they still have a genitive singular form inherited from PIE, unlike standalone articles. Note that the neuter singular has a -t- inserted before the article. The possessives are:

minso (mintat, minsá, mintí, mintá, mintás) "my, mine" - tuso "your (sg.), yours (sg.)" - suso "his/her(s)/their(s)" - nósso "our, ours" - usso "your (pl.), yours (pl.)"

As an example, only the declension of minso is given here:

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |

| Nominative | minso | mintat | minsá | mintí | mintá | mintás |

| Genitive | mintosy | mintassyá | mintyám | mintásam | ||

| Dative | mintási | mintasyé | mintós | mintábi | ||

| Accusative | mintom | mintat | mintám | mintás | mintá | mintás |

Pronouns

Lifashian pronouns are divided in three declensional paradigms: third-person pronouns follow the same declension as the articles (in fact, Lifashian articles are PIE third-person pronouns, while third person pronouns are the same forms preceded by le- (from the PIE emphatic particle *de)); the singular and plural first- and second-person pronouns have their own declensions, one in the singular and one in the plural.

Among first- and second-person pronouns, many of their forms have changed from PIE due to analogy, especially in the nominative and accusative.

Pronouns, demonstratives, interrogatives and correlatives still have genitive singular forms.

| First person | Second person | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular (I) | Plural (we) | Singular (you) | Plural (you) | |

| Nominative | mek | gis | tuk | yús |

| Genitive | mém | onsom | tet | usom |

| Dative | mew | onsyém | tew | usyém |

| Accusative | me | nó | to | yó |

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |

| Nominative | leso | lét | lesá | letí | letá | letás |

| Genitive | letosy | letassyá | letyám | letásam | ||

| Dative | letási | letasyé | letós | letábi | ||

| Accusative | letom | lét | letám | letás | letá | letás |

Note that contemporary Lifashian is said to have lost the T-V distinction, uniquely in its area of the world; previously, the second-person plural pronoun yús was used as the respectful form in both singular and plural.

This loss is a recent phenomenon that started in the early 1980s. There still is a noticeable generational divide, with T-V distinction being still commonly found among speakers born not later than the late 1950s; it is less common among people born in the 1960s and early 70s, and usually only used with older people.

Even in formal contexts, the remnants of T-V distinction are usually manifest in the use of turésysuás (Mr.) or ninfásuása (Ms.) with either the surname or - even more often - the given name. Using both the surname and given name is generally limited to written legal texts. It is not uncommon even for contemporary politicians or other prominent people to be mentioned in Lifashian newspapers with turésysuás/ninfásuása and their given name.

As in Russian (and possibly because of Russian influence), "X and I" is expressed through the first person plural plus sya (with) and the other name (in dative case because of the preposition); for example, "Scheherazade and I" would be expressed as gis sya Syahrzádehí.

This has given rise to an informal distinction between gis used as an exclusive first-person pronoun and an inclusive pronoun gis syam usyém (often contracted in speech to [ɡiʃæm(u)ˈʃeːm]).

Demonstratives

The two demonstratives - that can also be used as adjectives - distal hiˤn and proximal hiˤsy are declined as follows:

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interrogatives and correlatives

The interrogatives pis, pil "who, what" have their own declension, however similar to the first and second nominal ones.

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |

| Nominative | pis who? |

pil what? |

pá | peys | pá | pás |

| Genitive | pesy | pám | ||||

| Dative | pesyém | pábi | ||||

| Accusative | pim | pil | pam | pás | pá | pás |

The feminine singular and plural forms are generally used in indirect questions only instead of the interrogative adjective piyos, see for example:

- Mé memana, sya pábi tásam dánestélám lesit esyim. "I don't remember which ones among the professors I have spoken with."

The interrogative adjective piyos "which?" has a different declension, which has similarities to the one of the article in the singular nominative, and with nominal ones in other forms:

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |

| Nominative | piyos | piyat | piyá | piyí | piyá | piyehes |

| Genitive | piyosy | pissyá | piyásam | |||

| Dative | piyási | pissyehi | piyábi | |||

| Accusative | piyom | piyat | piyam | piyás | piyá | piyás |

The interrogative pronoun-adjective pihác? "how much?" and the corresponding correlative yosác "as much" follow nominal declensions (first for the pronouns and the masculine adjective, second and third respectively for the feminine and neuter, cf. the forms pihátá, pihátom)

The interrogatives/correlatives pop "when", pade "where", pé "how", pómat "why?" and yámat "because" are adverbials.

Adjectives

Adjectives follow a declension very similar to articles, although with slightly different endings, as they were originally articles attached to the end of (declined) nouns. The adjectival terminations are:

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |

| Nominative | -ás | -átat | -ása | -ésti | -(e)tá | -éssyes |

| Genitive | — | -átsám | ||||

| Dative | -étsim | -átasyé | -óstós | -áwtábi | ||

| Accusative | -átam | -átat | -ántam | -ástás | -(e)tá | -ástás |

Pronominal adjectives - such as polc "many" (f. poltá, n. poltom), somals "all" (f. somalá, n. somalom), himbi (f. himbá, n. himbim) "both" - follow nominal declensions, and have possessive forms. The pronominal adjective máˤn (f. máˤná, n. máˤnt) "no", however, is declined like the demonstrative hiˤn.

Nominalized adjectives have a special possessive form in -áh- for all genders. In older Lifashian, there were three forms (-ah- (masculine), -áh- (feminine), -eh- (neuter)), a distinction that eventually collapsed in favour of the feminine form (which has a long vowel like most nominative forms of the adjective) sometime around the mid-18th century across the whole Lifashian-speaking area.

Numerals

Cardinal numerals

Lifashian cardinal numerals are inflected for case only in the forms from 1 to 4 (and numbers ending in the digits 1-4), which also agree in gender with the noun, as well as 100 and 1000; however, while 1-4 have their own peculiar declensions, hundreds and thousands decline as nouns.

The numeral "one" has genitive singular forms instead of possessives.

The declension of 1-4 is as follows:

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Numerals from 5 to 10 are indeclinable:

| Digit(s) | Numeral |

|---|---|

| 5 | pembi |

| 6 | gésy |

| 7 | sutom |

| 8 | fastú |

| 9 | nún |

| 10 | lasyam |

The numerals 11-19 are compounds of the base numeral plus lasyam; however, due to historical reasons, the latter root may take three different forms: -lasyam after vowels, -tasyam after voiceless consonants, and -dasyam after all other consonants. In the case of 11-14, the first component is declined.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Digit(s) | Numeral |

|---|---|

| 15 | pembilasyam |

| 16 | géstasyam |

| 17 | sutondasyam |

| 18 | fastúlasyam |

| 19 | núndasyam |

The other numerals 20-99 follow the same overall rules:

|

|

100 is syandom and, unlike most other cardinals, it is declined for case and number as a third declension noun (with the stem syand- and accent on the ending). It does not combine with tens and units, and the number of hundreds may either be written separately or conjoined; conjoined writing is preferred in the formal language.

| Digit(s) | Numeral |

|---|---|

| 100 | syandom |

| 101 | syandom nyé m, syandom nyá f, syandom nyam n |

| 157 | syandom sutompembisyát |

| 200 | luyóˤsyandá |

| 300 | tírsyandá |

| 400 | pitórsyandá |

| 500 | pembisyandá |

| 600 | géssyandá |

| 700 | sutossyandá |

| 800 | fastúsyandá |

| 900 | núnsyandá |

Similarly, 1000 is the neuter noun hesyarom, also declined as a regular third declension noun. In the standard language, stress is on the first syllable of the stem. Unlike with hundreds, thousands are never written conjoined, e.g. 2000 luyó hesyará, 4896 pitór hesyará fastúsyandá gésynússyát.

Ordinal numerals

Ordinal numerals are regular adjectives. "First" and "second" are formed from roots different from the cardinals, while the others are formations from the same roots.

| Digit(s) | Numeral |

|---|---|

| 1st | hancás (first of many) farterás (first of two) |

| 2nd | sfetás (second of many) halyás (second of two) |

| 3rd | tartás |

| 4th | pitúrtás |

| 5th | penftás, dial. pembitás or pembutás |

| 6th | géstás |

| 7th | sutammás |

| 8th | fastumás |

| 9th | númmás |

| 10th | lasmás |

Adverbial numerals

Adverbial numerals are indeclinable adverbs meaning "X times". Numerals from 1 to 4 included are special forms, the others are regularly formed with the suffix -mát , an original suffixless locative (cfr. Skr. māti, A-Gr. μῆτις):

| English | Lifashian | English | Lifashian | English | Lifashian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| once | somi | 11 times | somi lasyammát | 111 times | syandommát somi lasyammát |

| twice | lis | 22 times | lis lílástimát | 200 times | luyóˤsyandámát |

| 3 times | ters | 33 times | ters tiresyámmát | 300 times | tírsyandámát |

| 4 times | pitrás | 44 times | pitrás pitóresyámmát | 400 times | pitórsyandámát |

| 5 times | pembimát | 55 times | pembipembisyámmát | 500 times | pembisyandámát |

| 6 times | gésymát | 66 times | gésyigéssyámmát | 600 times | géssyandámát |

| 7 times | sutommát | 77 times | sutonsutonsyámmát | 700 times | sutossyandámát |

| 8 times | fastúmát | 88 times | fastúfastúsyámmát | 800 times | fastúsyandámát |

| 9 times | númmát | 99 times | núnnússyámmát | 900 times | núnsyandámát |

| 10 times | lasyammát | 100 times | syandommát | 1000 times | hesyarmát |

Distributive numerals

Distributive numerals are generally regularly formed with the suffix -ír (possibly from -*ih₂-ros), with the exception of the first three numerals. They are adjectives, but are declined as nouns of the first (masculine), second (feminine), or third (neuter) declension. They are most commonly translated as "X each".

| English | Lifashian | English | Lifashian | English | Lifashian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one each | seméh (seméhá, seméhom) |

11 each | seméh lasymír | 111 each | syandír seméh lasymír |

| two each | liséh | 22 each | liséh lílástír | 200 each | luyóˤsyandír |

| three each | teréh | 33 each | teréh tiresyátír | 300 each | tírsyandír |

| four each | pitórír | 44 each | pitórír pitóresyátír | 400 each | pitórsyandír |

| five each | pembír | 55 each | pembipembisyátír | 500 each | pembisyandír |

| six each | gésyír | 66 each | gésyigéssyátír | 600 each | géssyandír |

| 7 each | sutonír | 77 each | sutonsutonsyátír | 700 each | sutossyandír |

| 8 each | fastúwír | 88 each | fastúfastúsyátír | 800 each | fastúsyandír |

| 9 each | núnír | 99 each | núnnússyátír | 900 each | núnsyandír |

| 10 each | lasymír | 100 each | syandír | 1000 each | hesyarír |

Distributive numerals (in the neuter plural, except for "one") are those used in spoken multiplication, e.g. lis liséhá pitór séti "two times two equals four" (lit.: twice (adverbial) two (distributive neuter pl.) are four (cardinal neuter)).

The related relational adjectives in -ónwás denote something "of X units", "consisting of X of something", e.g. hars hesyarírónwás "a village inhabited by 1000 people"; pulukam teréhónwátat "a three-part flag (a triband)"; elot pembírónwás "a group of five people, quintet".

Collective numerals

Collective numerals are used in order to count pluralia tantum or collective nouns. They have the form of fifth declension nouns used in the plural only (except for "one"); however, they do not decline for gender.

All collective numerals are regularly formed by adding -é (or -né after vowels) to the cardinal stem (hence without the endings for syandom and compounds), the neuter stem in the case of 4 (pitóré), with the exception of the irregular 1 (nyané), 2 (liyé), and 3 (teré).

Verbs

The verbal system of Lifashian is quite archaic among Indo-European languages: while overall morphological complexity has been reduced, notably through the use of analytic tenses, the system of synthetic verbs shows a late PIE stage where each root is independently conjugated in each tense-aspect combination, and the same root may have multiple primary formations; only verbs which are derived or borrowed with the addition of a secondary formant may be said to have a regular conjugation. Otherwise, a primary present formation can correspond to different past formations, or viceversa: see for example the root past eseraha which can mean either "I tied" (as past of serámi "I tie"), "I joined, built" (as past of serémi "I join, build"), or "I presented" (as past of the aorist form sisara "I present").

Endings

The following table lists the endings used in Lifashian verbs:

| 1SG | 2SG | 3SG | 1PL | 2PL | 3PL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endings (present)[6] |

-(á)mi | -(e)si | -(e)ti | -(a)mas | -(e)ti | -áti |

| Secondary endings (past) |

-(a)ha | -(a)ta | -a -Ø |

-(a)mát | -(a)dó | -ír -r |

| Perfect endings (aorist) |

-a -he |

-ta | -e | -me | -te | -é |

| Subjunctive endings (subj. and imperative) |

-m | -di | -tu | -we | -te | -tu |

Present

The Lifashian present formations are categorized as follows:

- class I (athematic verbs): root plus any personal suffix, without the -á- extension for the first person singular. This includes consonant-final roots (such as frál-mi "I become", dey-mi "I nurse", or with an epenthetic vowel eˤle-mi "I eat"[7]), but in many cases the Lifashian root ends in a long vowel and reflects an original laryngeal (such as mulú-mi "I say, speak" (PIE *mléwh₁mi)). The borrowed verbs siré-mi "I like" and guré-mi "I write" are also part of this class.

- class II (simple thematic): root plus extended personal suffixes. Overall the most common class, including e.g. syúp-ámi "I sleep", ber-ámi "I carry", hú-ámi "I touch", seˤl-ámi "I listen, hear", tarp-ámi "I dance".

- class III (nasal infix), athematic class with a stressed -ne- suffix inserted into the root in the singular and a -n- before the last consonant in the plural. Includes many common verbs, such as e.g. pure<ne>s-mi, pure<n>s-mas "I/we ask", sye<ne>l-mi, sye<n>la-mas "I/we have to", u<ne>l-mi, u<n>da-mas "I/we wash", tu<ná>-mi, tu<ná>-mas "I/we can" (less regular due to an original root-final laryngeal, still present in the root tuh-, cf. root past a-tú-m).

- class IV (reduplicated athematic), similar to class I but with a reduplicated initial, such as most notably le-lú-mi "I give", ge-wíl-mi "I watch, look at, gaze".

- class V (reduplicated thematic), similar to class II but with a reduplicated initial, e.g. si-syej-ámi "I hold", si-ll-ámi "I sit"[8].

- class VI (-númi verbs), adding -nú- in the singular or -nu- in the plural to the root. In Lifashian they were more commonly generalized than in other IE languages. Examples include istá-nú-mi "I raise", tarf-nú-mi "I turn", di-nú-mi "I feed, nurture, nourish", lor-nú-mi "I dream".

- class VII (-émi), the most regular formation, adds -é- to the root. An original primary formation (PIE *-é-ye-) is the second most common class, including common verbs such as e.g. pur-é-mi "I do, make", syál-é-mi "I fall", gil-é-mi "I see", far-é-mi "I tempt, allure, entice".

- class VIII (-iyámi), a regular formation that adds -iy- to the root, from secondary PIE *-eye-. It includes many common verbs, and was analogically extended to form the past -iyam class, a Lifashian innovation. Class VII verbs include e.g. native pít-iy-ámi "I count, reckon" as well as various verbs formed from borrowed nominals such as bón-iy-ámi "I build", cóc-iy-ámi "I cradle", salát-iy-ámi "I pray".

The imperative uses the same stem as the present, but with the subjunctive/imperative endings, except for the second person singular which has no ending. The first person singular imperative is never used.

Some verbs may indeed have irregularities that are not tied to the class system. For example, the common verb eynemámi "I take, get, seize, grasp" - which is a PIE prefixed verb whose unprefixed form is not attested in Lifashian - has stem allomorphy due to its stress placement: the two personal endings that are stressed (first person singular and third person plural) are added to the stem eynem-, while the others to the stem etinem-: eynemámi, etinemesi, etinemeti, etinemmas (contraction of older and more formal etinememas), etinemeti, eynemáti.

Aorist and Perfect

In Lifashian, the terms aorist and perfect are used for two (usually, but not always) synonymous forms, but they do not correspond to the PIE (or even Ancient Greek or Sanskrit) forms. In fact, the Lifashian aorist is the continuation of the PIE perfect, while the Lifashian perfect is a periphrastic form.

The aorist is used only with a limited number of roots: most of them have a present meaning (as with the PIE stative), but some of them have shifted meaning and are purely past tense forms. There are two aorist classes:

- class I (root), same as the corresponding PIE class, used for only two roots: inherited gyal-he "I know", and the lone Lifashian innovation lá-he "I have" (< *(s)leh₂g-h₂e, root láh-).

- class II (reduplicated), with a reduplicated initial, including the majority of aorists, e.g. ti-stá-he "I stand", le-lób-a "I love [a person]", si-sar-a "I present".

Aorists have two sets of endings, diachronically derived from the same ones depending on whether the initial laryngeal of the suffix is kept (cf. tistáhe (< *stestóh₂h₂e) and lelóba (< *lelowbʰh₂e)).

The perfect is a more recent formation. It is formed with a generalized past participle in -it (-t for vowel-ending roots)[9], formed starting from a past verb (with exceptions), and the appropriate form of the present copula:

- Mek tom filmom gilémi. "I see the film" (present); mek tom filmom lersyit (e)syim. "I have seen the film"

- Letasyé gortás poltás gurét e(sti). "(S)he has written her many letters."

In the spoken language and in informal writing, when used as auxiliary for the perfect, the present singular forms of the copula are syim, syi, e.

Certain verbs may have irregular or multiple participles, most notably frálmi, farhálm (I become, became, also used as passive auxiliary), which has the historically contracted participle frálit as an auxiliary, and uncontracted farhelit as a standalone verb. Certain meanings may be conveyed by different roots and it is possible for a different root from the past and present to be preferred in the perfect: while "I do" and "I did" is most commonly purémi and parm, the preferred participle for "done" is deˤt (actually cognate with English "do"), and not parit.

Past

Much like the present and aorist, the formation of the past in Lifashian reflects the original PIE past classes. Lifashian also uses an augment in front of all past verbs, with two possible forms: e- if the stem vowel is e or i, a- otherwise.

The four past classes are:

- class I (root athematic): more common than in other modern IE languages, it is simply formed by the root plus the suffixes. Forms other than the first person singular and third plural show extensive consonant assimilation. Plural forms often have different stems, reflecting PIE zero-grade. Examples: e-lersy-aha, e-lors-mát "I saw, we saw"; a-lúh-ha, a-lú-mát (underlying form a-luh-mát) "I, we created, made, prepared", é-ˤl-aha, e-deˤ-mát "I, we ate".

- class II (root thematic): overall the most common; class I and II together correspond to the vast majority of verbs in Lifashian. Root thematic past verbs generally have the same, regular forms in all persons. Examples: e-ber-aha "I brought", e-denah-ha "I ran".

Roots that belong to the present class VIII (-iyámi) keep the -iy- suffix in the past; see a-bón-iy-ha "I built", a-cóc-iy-ha "I cradled", e-pít-iy-ha "I counted". - class III (s-past, sigmatic): corresponding to Greek sigmatic aorist. Overall not as common as in other IE languages, but still represented. The added s is often obscured by consonant assimilation. See a-lúw-s-aha "I loved", e-gíj-aha (underlying e-gil-s-aha, from PIE *e-wéyd-s-h₂o) "I watched".

- class IV (reduplicated): very rare. The root is often quite obscured due to the stressed reduplication, zero-grade, and consonant assimilation. The few examples include e-lelah-ha "I had", or the literary a-gúk-ha "I said" (cf. Gr. εἶπον).

Pluperfect

The Lifashian pluperfect is an analytic tense, formed much like the analytic perfect, with the -it participle but with the past tense of esyim.

Example:

- Mek mey tom Rósom hóle safarom etinemit astám. "I had already travelled to Russia."

Future

The Lifashian future is a generally regular formation for all roots. It is an innovation formed by adding -(e)gi- to the root (or stem for class VIII presents) followed by the past endings (but no ending for the 3rd person singular); the future-forming suffix is likely a grammaticalized contraction of the root gil- "to see".

- Examples: paregiha "I will do", paregita, paregi, paregimát, paregidó, paregír

- denggiha "I will run", denggita, denggi, denggimát, denggidó, denggír

In colloquial Lifashian, the present alone is commonly used with a future meaning.

Subjunctive

The Lifashian subjunctive continues the PIE optative, but with its own distinct endings, which are a mix of secondary and imperative endings. It is formed by adding, to the root:

- For roots conjugated according to the present classes II, V, or VIII: -ó- in all persons;

- For all other roots: -ew- (stressed) in the singular forms, -í- in the plural ones (stressed on the ending).

The synthetic subjunctive is only used in the present. Examples:

- beróm (cf. pres. ind. berámi, class II), beródi, berótu, berówe, beróte, berótu.

- elewm (cf. pres. ind. elemi, class I), elewdi, elewtu, elíwe, elíte, elítu.

The subjunctive is used after most conjunctions, such as ent "in order to, cf. Latin ut". Example: Pambúgim ent somalam túnayam húóm. "I'll stay in order to hear the entire speech."

The copula, uniquely, uses the suppletive stem es(a)- for all forms.

Conditional

The conditional (also called hypothetical) is used to form conditional sentences; unlike e.g. Romance languages, but like neighboring Turkish and Azerbaijani, the Lifashian conditional is used in the protasis, e.g. Paláng sahét láseha, mey tám Ispániyam wakánsom etinenggim. "If I had enough money, I'd go on holiday in Spain."

The conditional is formed by adding -se- to the root with the past endings. Examples:

- berseha (root ber-) "if I brought", berseta, berse, bersemát, bersedó, berser.

There is also a past conditional (cf. "if I had had"), which is formed with the -it participle and the conditional of esyim, e.g. berit búseha "if I had brought". See e.g. Letám résy mé det búse, tám mosábakam esejmát. "Had she not been injured, we'd have won the match."

Compound verbs

A large part of contemporary Lifashian verbs is made up of compound verbs, not unlike Iranian languages, formed by a lexical element (often, but not always, borrowed) and a conjugable verb which provides little to no meaning; Lifashian also has nominal compound verbs, which are actually fixed collocations as the nominal is regularly declined in the accusative; however, such nouns are never used with articles in these fixed collocations, which often look like sentences with two objects.

The most common verbs used to form compounds are purémi "I do", lelúmi "I give", eynemámi "I take", and berámi "I bring". Other verbs include sisyejámi "I hold", esyim (the copula), or benámi "I go".

The lexical element is often an invariable adverbial element which may correspond to the stem of an adjective (either a native adjective - cf. ulmarstás "forgotten" and ulmarst purémi "I forget" - or a borrowed one - cf. tamízás "clean" and tamíz purémi "I clean") or a borrowed stem (from nouns, participles, or verb stems), such as in emansip purémi "I emancipate" (ultimately from French, through Russian), ámóht berámi "I teach" (from Persian), or espéti lelúmi "I wait" (from Ligurian).

Copula

| Present | Past | Perfect | Pluperfect | Future (1) | Future (2) | Subjunctive | Conditional | Past conditional | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1SG | esyim | astáha | búhit (e)syim | búhit astáha | present of frálmi "I become" |

buhegiha, búgiha | esam | búseha | búhit búseha |

| 2SG | esyi | astáta | búhit (e)syi | búhit astáta | buhegita, búgita | esadi | búseta | búhit búseta | |

| 3SG | esti | astá | búhit e(sti) | búhit astá | buhegi, búgi | estu | búse | búhit búse | |

| 1PL | somé | astamát | búhit somé | búhit astamát | buhegimát, búgimát | eswe | búsemát | búhit búsemát | |

| 2PL | iste | astadó | búhit iste | búhit astadó | buhegidó, búgidó | este | búsedó | búhit búsedó | |

| 3PL | séti | astár | búhit séti | búhit astár | buhegír, búgír | estu | búser | búhit búser |

All forms of the present, past, and subjunctive which begin with e- or a- form contractions with the preceding negative particle mé: mésyim, mésyi, mésti..., méstáha, méstáta, méstá...; mésam, mésadi, méstu...

Prepositions

(introduction TBA)

ep + dative sg./genitive pl. case "on"; + accusative case "onto". Also used for islands and riverside areas (see first example):

- So hars Muskuy ep tási hafní Muskuy esti. "The city of Moscow is on the Moscow river."

- So syorón ep tási selái syúpeti. – The cat is sleeping on the table.

- Góhará ng Kawádi ep Kufrom wakánsom etinemit séti. "Góhará and Kawádi have gone to Cyprus on holiday."

for + dative case: "for", "in favour of"

- For tew pótt alúhha. – I cooked dinner for you.

- Husein for tási heldúbatí mulúcam lefit e. – Husein voted for (in favour of) the proposal.

hó + accusative case: "from"

- So tulay nyam enseytorm hó tom ongim hewi bereti. – The boy is bringing a jar from the kitchen.

- Hó Dárom Hayám frádagi syari benggim. – I'm coming back from Armenia tomorrow.

lá + accusative case: marks an inanimate (or non-human neuter) ergative:

- Lá tom námirom mek polté kenitastasy ámóht eberaha. "The book taught me many new things."

- Deynepati lá at ígam so lúkéc apara ene hó tom hérom efersa. "Yesterday night the ice made the driver slide off the road."

lémí + dative case: "in the presence of"

- Tenúi hisési námirí lémí tasyé syárlúkétí sahwon amulúmát. "We had a talk about this book in the presence of the author."

li + dative sg./genitive pl. case: "behind" (state), "after" (in time); + accusative case "behind" (motion)

- Hin syorón li tasyé pardehí esti. "That cat is behind the curtain."

- Li tási tórwétí sá serwáná eyesa. "After the storm came the calm."

- Bé li at larun ng mém espéti lelú. "Go behind the tree and wait for me."

marw + accusative case: "as", "like", "being a(n)"; also used for languages (see third example)

- Nye syanangé marw nyam tákom esti. – a popular saying; (lit.) "A friend is like a jewel."

- Marw méliwútátam, histam lalimam mé sirémi. – Being an atheist, I do not like this wording.

- Parwáná mehwesi marw faransótátam mulúti, wate marw inggrízyátam. – Parwáná speaks good French, [but] bad English.

mey + dative sg./genitive pl. case "in", "inside of" (state); + accusative case "to", "in", "inside of" (motion)

- Sunuté minso nung mey tási lewírní esti. – My son is at (in the) school now.

- Duhaté minsá nung mey at lewírné benti. – My daughter is going to school now.

midi + dative sg./genitive pl. case "between", "among" (state); + accusative case "between", "among" (motion)

- Midihafnené sá dejá midi lúsy hafnenám esti. – Mesopotamia is the land between two rivers.

- Midi tás bóás benáti. – They walk between the cows and bulls.

nil + dative sg./genitive pl. case "at" (state); + accusative case "to", "at" (motion)

- Iréné siréti ene merpehi nil tási gulestái panesti. – "Iréné likes to spend the morning in the park."

- Nung nil tom bázárom benámi. – I'm going to the market now.

peli + dative sg./genitive pl. case "under" (state); + accusative case "under", "below" (motion)

- So syorón peli tási selái syúpeti. – The cat is sleeping under the table.

- So mús peli at selán gacewam eynemeti. – The mouse flees under the table.

pire + dative sg./genitive pl. case "in front of" (state), "before" (in time); + accusative case "in front of" (motion)

- Lámá minsá pire tasyé hettehí esti. – My house is in front of the church.

- Mé gyalhe at jahán pire ontarendórí. – I don't know [how] the world [was] before the Internet.

- So sów pire tám hettam benti. – The priest is walking [up to] in front of the church.

sya + dative case: "with"

- Helbenámi sya tasyé piwehí! – "I'll come with beer!"

- So helbart lámiyétam sya tós angurnyétuwi abóniya. – "The child built a little house with the toy bricks."

tenúe + dative case: "because of"

- Mánt mé elersyaha tenúe tasyé líssyehí. "I could not see anything because of the rain."

tenúi + dative case: "concerning, about"

- Syihámrey tenúi tós taruwi lífasyóstós syaismánsyóstós mulúgimát. "Today we will talk about contemporary Lifashian literature."

(more to be added)

Syntax

Word order

The unmarked word order in Lifashian is SOV:

- So syorón tom músom éla.

DEF.MASC.SG.NOM. cat.NOM.SG. DEF.MASC.SG.ACC. mouse-ACC.SG. eat.PAST-IND.3SG.

The cat ate the mouse.

Marked word orders are possible, usually for emphasis. For example, the particle le (< PIE *de), always in second position in a VS(O) construction, shifts focus to the subject:

- Esyim le mek.

be.PRES.IND.1SG. EMPH_PARTICLE. 1SG.NOM.

It's me.

Split ergativity

Lifashian has an animacy-based split ergativity, traced back to an areal feature of ancient Anatolia, possibly to the Hurro-Urartian languages. In Lifashian, all neuter nouns unless explicitely referring to people and all non-neuters not referring to people, animals, or certain personified concepts[10], exhibit this feature when agents of transitive verbs. In those sentences, the patient is still in the nominative and agrees with the verb, while the agent is preceded by the particle lá (which requires accusative case). For example, with the verb kúrhíyámi (I assault, attack, haunt, critique):

- Fikarás sutás kúrhíyámi. (I critique, am against his/her/theirSG opinions.)

- Lá yádás mintás kúrhíyámi. (My memories haunt me.)

Even so, there is a prohibition against using inanimate agents for certain verbs that may imply volition: e.g. a sentence such as *lá tom népom ebelem "the vase hit me" is still ungrammatical, and so it has to be reformulated by explicitely marking the non-volitive action implied, i.e. so néps asyájat ng mek belit farhálm. "the vase fell and I was hit". Note the use of the passive in this standard sentence, but in colloquial registers the absolutive alignment is still used even without lá, i.e. so néps asyájat ng mek ebelem.

Relative clauses

Relative clauses in Lifashian are constructed in two ways, both with the conjunction (in one case)/particle (in the other) ene.

The first method consists in an adjoined, nonreduced, relative clause:

- Mek tám ninfam deyhámrey elersyaha ene (lesá) lámam ebena.

1SG.NOM. DEF.FEM.SG.ACC. woman-ACC.SG. yesterday. see.PAST-IND.1SG. REL. (3SG.FEM.NOM.) home-ACC.SG. go.PAST-IND.3SG.

The woman I saw yesterday went home.

The second method, a probable Kartvelian influence due to a similar construction being also found in Georgian, consists in embedding ene with a resumptive pronoun in the relative clause. In this case, the two sentences are separated by a comma:

- Mek ene letám deyhámrey elersyaha, sá ninfá lámam ebena.

1SG.NOM. REL. 3SG.FEM.ACC. yesterday. see.PAST-IND.1SG.

The woman I saw yesterday went home.

As in Georgian, the head noun can be in the relative clause; unlike the case with conjunctive ene, a resumptive pronoun must be used in this case.

- Mek ene tám ninfam deyhámrey elersyaha, lesá lámam ebena.

1SG.NOM. REL. DEF.FEM.SG.ACC. woman-ACC.SG yesterday. see.PAST-IND.1SG.

The woman I saw yesterday went home.

PIE dual

The PIE dual is not continued anywhere as a standalone category in Lifashian, but it left its mark in certain oppositions where constructions denoting dual number are treated differently from both singular and plural. These include:

- Two different ordinals for "first" and "second": hancás and ispétás used for three or more things, farterás and halyás used for exactly two things;

- The construction himbi lú for "all two" (lit. "both two"), while quantities from three onwards use "all", i.e. somals teri, somals pitúri, somals pembi and so on;

- The form lilásti for twenty (an original dual) vs. tiresyát, pitóresyát, and so on, continuing PIE plurals.

Vocabulary

Through its history at the crossroads of Europe and Asia and the long contact between languages resulting from the millennia through which the Lifashians were always subjects of foreign powers, the vocabulary of Lifashian has been enriched and shaped by the absorption of plenty of loanwords, which certainly dates back to Lifashian prehistory. The vast majority of loanwords, also, are considered to be fully integrated in the language, helped by the fact that all of them (except some proper nouns) are transcribed into the Lifashian script and are adapted to fit native morphology.

The share of loanwords is not uniform in the Lifashian vocabulary. First of all, the vast majority of borrowed words in any stage of the language are nouns, and the number of borrowed adjectives with no corresponding noun, while not small on its own, is far smaller. Borrowed verbs are a very small number, and nearly all of them are formed through the suffix -íy- that also served to form verbs from other parts of speech. Note that in more recent times (from the 18th century onwards), nearly all new verbs that have entered Lifashian are compound verbs, and new compound verbs have also displaced full verbs; the verbal part of compound verbs, which contributes little meaning of its own, is nearly always a native Lifashian (PIE-inherited) root. The only very common Lifashian verbs which are loanwords and do not have the -íy- suffix are gurémi (I write) and sirémi (I like), both loanwords from Armenian.

Moreover, loanwords are not evenly distributed in terms of frequency; all function words are native, inherited from Proto-Indo-European, as are many of the most commonly used words, so that the most basic forms of the language contain mostly native roots. However, very basic words are not always native, sometimes due to semantic drift that has caused loanwords to fit into the other meaning. Almost as a counterpoint to basic words being mostly inherited roots, nearly all Lifashians carry given names that are borrowed: most of them from Middle Persian, while Western names are typically borrowed through Medieval Greek or through Ligurian; Islamic theophoric names are borrowed from Arabic.

Among borrowings, the most ancient layer was borrowed in the Lifashian prehistory, and some of them are of disputed etymology. However, while not all words attributed to those sources may effectively be loanwords, there definitely is a prehistorical layer of borrowings that likely dates back to the first coming of Lifashians into eastern Anatolia, consisting of loanwords attributed to ancient languages of the Near East: Hurrian, Urartian, and Akkadian. Nearly all of proposed etymologies attributed to these languages belong to (or originally entered the language in) the semantic fields of animals, plants, agriculture, and early technology; some examples are syorón "cat", lesp "honey", tufné "box" (from Akkadian), henjá "apple", syelur "plum", probably neht "bed" (from Hurrian), hér "road" (attributed to Urartian). The names of the first six planets[11] - excluding Earth - are also likely Akkadian-mediated loans of ancient Mesopotamian words. Words generally attributed to Indo-European Anatolian languages are most likely to be influenced, areal, or calques, as the phonological shape does not always support the hypothesis of direct borrowing.

A few dozen words are generally categorized as Iranian loans, being either early loans from Proto-Iranian or mediated by other unspecified languages: such words include mirajé "rice", súftá "milk", possibly nársé "woman".

The largest share of loanwords into Lifashian comes from Persian, and they were borrowed from different dialects of Persian at different times in the space of nearly 2000 years. Persian loanwords are found in every semantic field, from many everyday words (seasons, e.g. tábestán "summer", bahár "spring"); words related to general urban life (syahr "city", meydán "square"); knowledge (námé "book"; dánesy "knowledge"); agriculture (zardálá "apricot"), to more abstract concepts (firdáws "paradise", yádi "memory, remembrance"). More abstract concepts, ethnonyms, and Islam-related words come from Arabic but in the vast majority of cases they entered Lifashian through Persian, so they are usually considered of Persian origin too; such words include e.g. Dár "home (used as "homeland" or with a genitive as "country of", cf. Dár Lífasyám but also Dár Hayám (Armenia), Dár Pársyám (Iran, sometimes referring to Greater Iran) and even Dár Ondúhám (a possible name for Earth, literally "home of the people")", táj "jewel", haylá "family", akbar(syás) "great".

Dating back to the first millennium CE are also likely most Armenian loans, which also cover many semantic fields, but more everyday words than Persian loans; they include the previously mentioned gurémi "to write" and sirémi "to like", but also e.g. órén "rule; law", tatum "pumpkin", tulay "boy", yo "yes", hamár "number". Also from the early first millennium (around the time of the earliest attestations of Lifashian) are the Aramaic loans, introduced alongside Syriac Christianity and generally limited to that semantic field, such as hettá "Church; a church", násrey "Christian", mahmolítá "baptism", sów "priest", Esyuh Misyihów "Jesus Christ"; there are also a few Aramaic loans not strictly related to Christianity, such as lap "paper".

Greek loanwords belong to two layers: a smaller, earlier one with more varied semantic fields (kawnás "blue", ninfá "woman", falem "room", istíryás "rigid") and a later one, generally used in scientific terms as e.g. linguistics (kilisi "declension", pitosi "grammatical case", oristikás "indicative (mood)").

During the Middle Ages and Early Modern Era, during Genoese rule, various Ligurian terms entered the Lifashian language: many of these relate to administration or commerce (paláng "money", dyugangá "customs", bitégá "shop", pázyi "government palace"), nautical terms (rutá "route", lengtarná "lighthouse", istíwá "hold"), but also a few general words (jastémá "blasphemy", lélwá "ivy", dupostás "indigenous", mangdili "handkerchief") as well as certain foodstuffs, although these were probably introduced later, from the Ligurians settled on the Lifashian coast (tuki "sauce", sézyá "cherry", fyugasá "(Genoese) focaccia").

The most recent substantial layer of loanwords is from Russian, which includes most words that have entered the language in the 20th century. They are mostly modern concepts, such as haladilnik "fridge", milíciyá (Militia, police (until 2005)), poyist "train" (but kárbáné, itself ultimately a loanword from Middle Persian, has been the preferred term since the 1960s, and virtually the only term after independence), tilivizar "TV set" (but note the calque lúrgiltá, used for "television" as a medium or technology). However, a very large number of 20th century neologisms, and especially since Lifashian independence in 1991 (which has markedly influenced the language in the following decades due to the increasing Lifashian patriotism, as for the first time the Lifashian state is an independent country not ruled by any foreign power), has been composed of calques, often from Russian, Greek, or internationalisms. Some calques from Greek or internationalisms were already coined during the 19th century, as e.g. lámadánesy "ecology". Calques or semantic calques include syaselman (council, committee; coined in the 19th century as a calque of Greek συνέδριον; later acquired the sense of “Soviet” as a semantic calque of Russian совет); halhámor (update, calqued from French ajourner), jámehtuwá (socialism); calques or partial calques from English are particularly common in words about computers and IT, such as píttorm “computer”, embentél “drive”, páwehiksy “firewall”, rakomíyás “digital”; sometimes, the new meanings have been added to preexisting words, as in the case of gort “file”, previously just “document” (itself one of the dubious Akkadian loans) or hesyow “account”, previously just “register”. In fact, it is extremely rare for new words to be borrowed, and not calqued or somehow adapted, into Lifashian.

Some words introduced in recent years are actually loanwords: for example, the new Lifashian currency introduced in 2002 is the zenuíng, named after the Genovino (Lig. zenoín), an old Genoese coin, and its subdivision is the sódi (ultimately cognate with Italian soldo); similarly, the Lifashian police reformed in 2005 is named dárigán after one of the court guard formations of the Sasanian Empire (despite modern Dár Lífasyám itself only being briefly – and negligibly - part of the Sasanian Empire).

Days and months

|

|

|

Dár Lífasyám is one of the few countries in the world that does not use the Gregorian calendar, and notably it is the only one that reverted to its national calendar after using the Gregorian one for seven decades (during the Soviet period).

The current Lifashian calendar is the Solar Hijri (Iranian) calendar but counting years since (Gregorian/Julian) 1917, the year of the October Revolution; the month names are mostly the Persian ones also used in Iran, which were the ones traditionally used by the Lifashians before adopting the Gregorian calendar in 1918: the Lifashian names are slightly different from the current Iranian ones as they were mostly borrowed in Lifashian prehistory, from Early Middle Persian; three of the month names (Khordad, Aban, and Dey) are old calques rather than borrowings.

The Iranian calendar had been unofficially used all throughout the Soviet era, and the shift from the Gregorian calendar to it (with the year numbering change) was approved in 1992, right after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and Lifashian independence; the calendar entered official use on Nowruz 77 (21 March 1993). In Dár Lífasyam, 20 March 1993 was followed by 1 farwardín 77.

Years before 1917 are counted backwards and marked in writing with the abbreviation p.R., "before the Revolution" (pire tasyé Rewalúciyehí); 1916 is 1 p.R. in the Lifashian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is unofficially used in international (and non-Greater Iranian) contexts, but historical dates e.g. in school textbooks are always cited and learned in the Lifashian calendar only; it is also used by the ethnic minority of the Lifashian Ligurians and by the Roman Catholic Church in Dár Lífasyám, which uses it to determine the dates of Catholic holidays; the dates of Orthodox holidays (by the Lifashian Syriac Orthodox Church, the largest religious denomination in the country, which is non-Chalcedonian) are similarly determined using the Julian Calendar. Interestingly, as the Julian calendar was first spread during the Middle Ages and Early Modern Era, during the period of Genoese rule over Dár Lífasyám, the Gregorian (and Julian) month names in Lifashian are derived from Ligurian.

In Dár Lífasyám, the weekend is actually referred to as the beginning of the week (syawacárs) as Saturday and Sunday are the first two days of the week in the Lifashian calendar.

Lifashian public holidays

Public holidays and other festivities - which, in Dár Lífasyám, are for the most part the same as in the Soviet era - were realigned either based on the date of the historical event they are based on, or on what day of the Solar Hijri calendar they fell on in 1992.

- Nowruz (Nawróz): 1-4 frawortín; Nowruz is the main holiday in Dár Lífasyám and it is celebrated by all ethnic groups of the country. A broader two-week period of Nowruz holidays is the general holiday season in the country and all schools are closed during those days, much like Christmas holidays in Western countries.

- Day of the International (hámor Kútebénesyáhs): 11 and 12 ardowhist (celebration of International Workers' Day; the days correspond to Gregorian 1/2 May in most years)

- Victory Day (hámor Sejmahs): 19 ardowhist (commemorating the Victory over Nazi Germany on 9 May 1945 / 19 ardowhist 29)

- Day of Peace and Freedom in the World (hamor Serwánáhs ng Ázáditáhs mey Dejehí), often referred to by left-wing parties as Day of the Liberation from Colonialism and Imperialism (hámor Hótarpetiyéhs hó tam Mostahmartuwam ng Iluhántuwam): 24 liftá (introduced in 1999; the date commemorates the birth of Ernesto "Che" Guevara on 14 June 1928 / 24 liftá 12)

- Day of the Renaissance (hámor Anajencáhs): 26 amartát (commemorating the death of Dótfaren Lilháti, a prominent poet and philosopher of the Lifashian Renaissance, on 17 August 1646 / 26 amartát 271 p.R.)

- Day of the Constitution (hámor Syadúbmahs) : 14 ksyahrbér (commemorating the signing of the Lifashian Constitution on 5 September 1992 / 14 ksyahrbér 76)

- Day of the Revolution (hámor Rewalúciyahs otúbriha): 16 hehnsúns (commemorating the October Revolution on 7 November 1917 / 16 hehnsúns 1)

- Day of the Memory of Lenin (hámor yádihs Leninahs): 1 bohman (commemorating the death of V.I. Lenin on 21 January 1925 / 1 bohman 8). Reintroduced in 1995.

- International Women's Day (hámor kútebénesyás tásam ninfehám): 18 isfendárm (corresponds to 9 March in most years, but the date was fixed on the occurrence in 1992)

The Day of the Paris Commune (hámor komúnahs Parízyihs) on 27 isfendárm, commemorating the uprising of the National Guard of Paris on 18 March 1871 / 27 isfendárm 46 p.R., had been reintroduced in 1998 after being a holiday in the early Soviet era; however, after three years, it was removed from the list of public holidays as it was deemed too close to Nowruz anyway; the Day of the Renaissance was instituted to replace it.

Members of the three main religious confessions of Dár Lífasyám (Orthodox Christians, Muslims, and Catholics) celebrate as de facto "religious public holidays" the main religious holidays of their faith: Christmas (Libajencá) and Easter (Zátegi) for Christians and Eid al-Adha (Hedekorbán) and Eid al-Fitr (Hedolfetr) for Muslims. According to national laws, everyone has the right to get days off work on the dates of their religion's main holidays; municipalities with particular minorities can decide to declare local public holidays on those days. The dates of these holidays are calculated using the Julian calendar for Eastern Orthodox Christians, the Gregorian one for Catholics, and the Islamic calendar for Muslims. Lifashian Christians celebrate Christmas on the same date as Theophany, using the Gregorian date (as do Armenians), corresponding to 16 or 17 lefón depending on the year in the Lifashian calendar.

Time and date

Dates are numerically represented as year-month-day with leading zeros omitted, e.g. 105-1-20. The officially preferred written form is 105, 20 frawortín, but the alternative 20 frawortín 105 is also commonly used and accepted. Day and month names are never capitalized.

Time is expressed officially with the 24-hour clock. In writing, hours and minutes are separated by a colon or by a lowercase letter sy (standing for syaht(i) "hour(s)"), e.g. 11:23 or 11sy23 (cf. Latin script notations such as 11h23). In speech, 24-hour times are spoken as 11 syahti 23 (nyastasyam syahti tisyardílásti), with a masculine numeral for the hours (implying masculine syaht) and a feminine one for the minutes (implying feminine dakíká).

In speech, unless precision is needed, a form of 12-hour clock is used, however it is never written unless each word is spelled. A hour is generally divided into quarters (and/or, mostly among older people or in rural areas, thirds) and each quarter, half, or third always refers to the following hour, as in the following examples:

- 9:00 – nún syahti

- 9:15 – pitórisyása lasyam, literally "a quarter of [hour] ten"; note how fractions are always feminine, implying istísá "part".

- 9:20 – tírisyása lasyam "a third of [hour] ten"

- 9:30 – keltása lasyam "half ten"

- 9:40 – luwá tírisyéssyes lasyam "two thirds of [hour] ten"

- 9:45 – tisyar pitórisyéssyes lasyam "three quarters of [hour] ten"; often contracted in speech as *tisy-pitórsyes

Hours are always represented by cardinal numerals, and they decline (or are invariable) accordingly, as in e.g. 12:30 keltása nyasy, 13:30 keltása lúsy, 14:30 keltása taryóm, 15:30 keltása pitrám, 22:30 keltása nyastasyam, 23:30 keltása lústasyam.

In order to disambiguate in speech between a.m. and p.m., tassyá merpehi "of the morning" and tosy wisferé "of the evening" are used respectively; sometimes, tassyá beltehi, literally "of the light", is preferred for p.m. hours before dusk.

Kinship terms

Lifashian has one of the most complex kinship terminology systems among Indo-European languages. It has an obligatory distinction of age among siblings and parallel cousins, and a distinction in the treatment of parallel and cross cousins.

- máté "mother", faté "father"

- bárté "older brother", hanité "younger brother"

- eláté "older sister", súsyáté "younger sister"

- sombalbás "sibling; sibling from the same mother" (adj.); cognate with Greek ἀδελφός

- aunts: tatéyá "mother's sister", mámenyé "father's sister"

- uncles: tatáy "father's brother", húhas "mother's brother"

- parallel cousins: tambárté "older male first cousin", tahani "younger male first cousin", taleláté "older female first cousin", tússyá "younger female first cousin"

- cross cousins: húhsyís "mother's brother's son", húhsyená "mother's brother's daughter"; mámesyís "father's sister's son", mámesyená "father's sister's daughter"

Texts

Schleicher's Fable (So masy ng tí esyúi)

- Nyé masy, pesy hawláná ne astá, elersya esyúás; nyé nyam arikam karetántám etenga, nyé nyim tangtom duwsátam ebera, nyé lengom nyim turésyom ebera.

- So masy tós esyúwi amulú: «Mintat syardém duwsom résy mewi puréti, pimbe turésyom, esyúám lúkétom, gilémi.»

- Tí esyúi tási masyí amulúr: «Hú, a masy! Mintá syardéa duwsom résy ósmi puréti, pimbe histom gilémas: nyé turésy, so kirius, et tosy masyé hawlánam eynemeti. Dán máná hawláná ha tosy masyé esti.»

- Histom esela, so masy gacewam ham at peliné etinema.

- [ɲeː mæʃ peʃ hæu̯ˈlɑˤːnɑː ne æʃˈtɑː eˈlerʃæ eˈʃuː.ɑːs . ɲeː ɲæm ˈærikæm kæreˈtɑːntɑːm eˈteŋæ . ɲeː ɲim ˈtæŋtom duu̯ˈsɑːtæm eˈberæ . ɲeː ˈleˤŋom ɲim tuˈreːʃom eˈberæ]

- [so ˈmæʃ toːs eˈʃuːwi amuˈluːˤ . minˈtæt ʃærˈdeːm duu̯som ˈreːʃ mewi puˈreːti . ˈpimbe tuˈreːʃom . eˈʃuːɑːm luːˈkeːtom . ɡiˈleːmi]

- [tiː eˈʃuː.i tɑːsi ˈmæʃiː amuˈluːr . huː æ ˈmæʃ . minˈtɑː ʃærˈdeː.æ duu̯som ˈreːʃ oːsmi puˈreːti . ˈpimbe ˈhistom ɡiˈleːmæs . ɲeː tuˈreːʃ . so ˈkirjus . et toʃ ˈmæʃeː hæu̯ˈlɑˤːnæm ei̯ˈnemeti . dɑˈn ˈmɑˤːnɑː hæu̯ˈlɑˤːnɑː hæ toʃ ˈmæʃeː eʃˈti]

- [ˈhistom eˈselæ so ˈmæʃ ɡaˈtʃewæm hæm at ˈpelineː etiˈnemæ]

Notes

- ^ The conjunction ng (and) itself is a partial exception, as it represents spoken /oŋ/, or /-ŋ/ after vowels, and is not a standalone word.

- ^ This form is attested in early Lifashian; later Lifashian borrowed an -adá suffix from Medieval Greek, so that the modern form of this name has been archaized as Driádá.

- ^ Some extremely conservative inland dialects have hamza on unstressed vowels too; in the standard, it sometimes occurs in careful speech in some prefixes and words derived from those, such as efter "higher" /eˤfˈter/, from the prefix eˤp-.

- ^ See also, for a similar process where grammatical gender is productively used in semantic loans, robbán, an originally Arabic loan which means "navigator" as a masculine first declension noun, but in recent decades has gotten the new meaning (calqued from English) of "web browser" as a neuter third declension noun. In this case, the feminine form (female navigator) is different, robbánetá.

- ^ Five countries: Dár Lífasyám, Dár Hayám (Armenia), Dár Pársyám (Iran), Dár Turkám (Turkey), and Dár Yúniyám (Greece).

- ^ The vowel added between brackets is the one used in the thematic classes.

- ^ Synchronically irregular due to consonant assimilation: eˤlemi, eˤtsi, eˤti, deˤmas, deˤte, déˤti.

- ^ From PIE *sísd-oh₂-mi; the synchronic root is sel-, as shown in derivations such as selt "seat", syaselman "council", farseléc "president" (the latter two calqued from Greek).

- ^ Other participle forms did not survive as verbal forms, although there are traces in Lifashian. The present active participle ended up being the nominalizing derivational suffix -éc (< *-ent-s), while the *-wo-s past active participle remains in some nouns as well as in relic adverbs or expressions such as mé hentibúwot "despite" (-wot being a relic proto-Lifashian ablative *-wōt, a case that disappeared from modern Lifashian).

- ^ For example, seasons are considered animate, as are some feelings and happenings (e.g. "peace", "war"), as well as entities constituted by people (e.g. "the State", "government", other similar metonymies)

- ^ Nów, Istérá, Nilkéri, Morlók, Nenórs.