Weddish: Difference between revisions

(→Others: I was gonna add each letter, but this is just easier.) |

m (small stuff) |

||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

| '''ז''' <tt>/z/</tt> | | '''ז''' <tt>/z/</tt> | ||

| '''זש''' <tt>/ʒ/</tt> | | '''זש''' <tt>/ʒ/</tt> | ||

| | | '''ר''' <tt>/ʁ/</tt> | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

| '''ל''' <tt>/l/</tt> | | '''ל''' <tt>/l/</tt> | ||

| '''י''' <tt>/j/</tt> | | '''י''' <tt>/j/</tt> | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 177: | Line 177: | ||

When necessary to avoid confusion, <tt>/u/</tt> can be precisely specified with a '''וּ''', called a '''šurek'''. <tt>/i/</tt> can be invoked as '''יִ''', that is a '''yud xirek'''. | When necessary to avoid confusion, <tt>/u/</tt> can be precisely specified with a '''וּ''', called a '''šurek'''. <tt>/i/</tt> can be invoked as '''יִ''', that is a '''yud xirek'''. | ||

==== Others ==== | ==== Others ==== | ||

Yiddish has many loanwords from Hebrew and Aramaic which are written using the Hebrew abjad in the Semitic way. Weddish, however, writes these words out according to its own orthographic conventions. | Yiddish has many loanwords from Hebrew and Aramaic which are written using the Hebrew abjad in the Semitic way. Weddish, however, writes these words out according to its own orthographic conventions. There are times when it is necessary to use the ancient letters, especially in religious settings. | ||

{| {{Table/bluetable}} | {| {{Table/bluetable}} | ||

! Lošn Koydeš Letter | ! Lošn Koydeš Letter | ||

| Line 196: | Line 196: | ||

|} | |} | ||

There is also a highly ornate style of writing Weddish, called '''xtiv qoydeš''' (holy writing, abbr. x"q) | There is also a highly ornate style of writing Weddish, called '''xtiv qoydeš''' ("holy writing", abbr. x"q) where letters are used not as an alphabet, but as an abjad. Vowels may or may not be written in this style. When written, they are written as diacritical marks ("points") around the consonants. In this style, '''v''' is written as '''ו''' and '''y''' as '''י'''. Vowels are as follows, with the '''א''' written as necessary: | ||

{| {{Table/bluetable}} | {| {{Table/bluetable}} | ||

! Standard | ! Standard | ||

| Line 250: | Line 250: | ||

== Phonotactics == | == Phonotactics == | ||

Weddish phonotactics are inherited from Yiddish, which | Weddish phonotactics are inherited from Yiddish, which are quite permissive on the world scale<ref>http://wals.info/chapter/12</ref>. While they do not rise to the level of Georgian or Salish, they are nevertheless difficult for English speakers. Gemination only becomes phonemic across word boundaries. Consonant clusters are spontaneously broken up across syllables in order to make codas less complicated and, if necessary, onsets more so. | ||

=== Syllabic Consonants === | === Syllabic Consonants === | ||

Liquids and fricatives may | Liquids and fricatives may be said syllabically. Syllabic consonants occur at the end of a word. In an unstressed syllable, syllabic sonorants and syllables with a reduced vowel are indistinguishable. In stressed syllables, no vowel is written, the onset and coda are optional or may consist of a single stop. | ||

=== Onsets === | === Onsets === | ||

| Line 827: | Line 827: | ||

=== Formality === | === Formality === | ||

=== Particles === | === Particles === | ||

By far the most commonly occurring particle is '''v-''', which is like a verbal comma. Yiddish - like English - has the word and/'''un'''. Weddish, however, only uses that word to connect clauses. '''v-''' is a return to Hebrew, though typically not at the start of sentences. | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Languages]][[Category:Conlangs]][[Category:Germanic languages]][[Category:Semitic languages]][[Category:A posteriori]] | [[Category:Languages]][[Category:Conlangs]][[Category:Germanic languages]][[Category:Semitic languages]][[Category:A posteriori]] | ||

Revision as of 03:24, 14 February 2014

| Weddish | |

|---|---|

| Vediš | |

| Pronunciation | [/ˈve(ː).dɪʃ/] |

| Created by | Robert Murphy |

| Date | 2013 |

| Setting | Jewish intermarriage / Systematic Theology |

| Native speakers | 0.01 (2014) |

Indo-European

| |

| Sources | Yiddish |

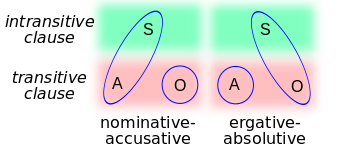

Weddish (Weddish: װעדיש, X"Q: וֶדִש, Romanization: Vediš) is a constructed, a posteriori, naturalistic auxlang, made from Yiddish with heavy influences from Hebrew, English, German, and some Basque. It has ergative-absolutive morphosyntactic alignment and a pervasive yet symbolic use of the dual. It is meant to promote the institution of marriage, foster better communication between persons, and improve the tenor of Systematic Theological discussions. It is well-suited as an auxlang for Jewish intermarriage.

The language was created in 2013 by Robert Murphy as part of an assignment at Covenant Theological Seminary for Professor Jerram Barrs.

Philosophy

First and foremost, there is the Creator-Creature distinction. That means, God is wholly other than the Universe. Second, human beings are made in the image of God. This means that we are persons -- like God is -- and our agency is our single-most important feature. Third, we reflect the image of God as females and males. The marriage bond is God-created and a fundamental part of our identity in this life. Hence it is, that we may divide the world into: actors, non-actors, and actions. Stated grammatically, this list becomes: ergative nouns, absolutive nouns, and verbs. Furthermore, ergative nouns may be divided up into married and non-married actors, which we will mark with the dual or not.

We have said that ontologically speaking, there are ultimately only two (God and not-God). However, the 800lb. gorilla in the room -- philosophically speaking -- is abstraction. Since before Pythagoras, abstract nouns (such as numbers, "goodness", etc.) had been held by the Greeks to be ontic. Westerns betray their affinity to Greek ideal, classifying humanity as homo sapiens - "thinking man". We seek to disenthrall ourselves from this metaphysic and banish abstract nouns from our language. Numerals are adjectives. Infinity is that which we cannot see the end of. Universals are the same as aggregates ("all" is the same as "sum" ... but not "some"!).

The Language Creation Society (as fine institution) waves a flag of the Tower of Babylon. Unlike the hubristic man of the initial chapters In the Land of Invented Languages (Arika Okrent's chronicle), we do not believe we can undo by human effort what God has done. Our aim is for Jews and Christians to discuss the truth better. The status of English as a lingua franca, German as a language of science, and Hebrew as a holy language suggests that an Indo-European language is still the best option for an a posteriori auxlang. Rather than compete with those vital languages, however, it seems most prudent to build upon a base off them all at once, utilizing a language that is already as eclectic as English, yet built off German and Hebrew. That language is Yiddish.

Phonology

Weddish has 25 consonantal sounds, which is typologically average [1], and common in Europe as well as the Middle East. English speakers will find it to be common, apart from the lack of /w/ and the ubiquity of /x/ (like the ch in Bach or loch). Weddish has 6 vowels, which is also average[2], as is the resulting consonant-to-vowel ration[3]. This is typologically equivalent to Yiddish and Hebrew, but far less than German or English.

| Consonant phonemes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labial | Alveolar | Post-Alveolar | Dorsal | Glottal | ||||

| Nasals | מ /m/ | נ /n/ | * /ŋ/ | |||||

| Stops | voiceless | פ /p/ | ט /t/ | ק /k/ | א /ʔ/ | |||

| voiced | ב /b/ | ד /d/ | ג /g/ | |||||

| Fricatives | voiceless | פֿ /f/ | ס /s/ | ש /ʃ/ | כ /x/ | ה /h/ | ||

| voiced | װ /v/ | ז /z/ | זש /ʒ/ | ר /ʁ/ | ||||

| Affricates | voiceless | צ /ts/ | טש /tʃ/ | |||||

| voiced | דז /dz/ | דזש /dʒ/ | ||||||

| Approximants | ל /l/ | י /j/ | ||||||

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | י /i/~/ɪ/ | ו /u/~/ʊ/ | |

| Mid | ע /e/~/ɛ/ | /ə/ | אָ /o/~/ɔ/ |

| Low | אַ /ɐ/~/ä/ |

| +y | +w | |

|---|---|---|

| a | ײַ = ay | אַו = aw |

| e | ײ = ey | |

| o | ױ = oy | אָו = ow |

Voices is contrasted in both plosives and fricatives, like Yiddish and English[4]. Vowel nasalization and rounding are not phonemic[5]

There are several issues in the pronunciation of individual sounds. The rhotic of Weddish is either alveolar or uvular[6] and may be anything from a flap, to a trill, to an actual approximant. No R-colors vowels are permitted. Words that begin with a vowel are separated from a prior open syllable by a glottal stop. The velar nasal only occurs when an "n" is assimilated in place of articular before or after an "x", "k", or "g", in a syllable coda[7]. ng is pronounced /ŋg/, not just /ŋ/. L is typically dark (aka "velarized") except before i. Ayen is always romanized e, but signifies the schwa in unaccented syllables.

In the dialect of the Americas, central vowels retain a color of their original/short form. Elsewhere, they are all central, except /a/ before glottals and /ɪ/ before labials. Another dialect difference is that c and dž are pronounced /θ/ and /ð/[8]. However, the rhotic is still not retroflex!

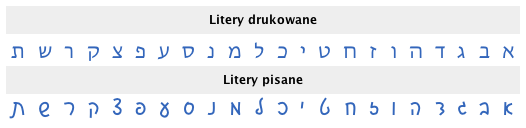

Orthography

Weddish written in the Hebrew alphabet, after the standard of YIVO Yiddish. There is a one-to-one correspondence between grapheme and phoneme, except for three digraphs and one trigraph. Weddish also has its own Romanization scheme, largely Slavic in appearance. In it, /ʃ/ is written š, /ʒ/ is written ž, /j/ is written y, /ts/ is written c, /tʃ/ is written č, /dʒ/ is written dž, and /ʁ/ is written r.

If the syllable after a diphthong begins with a vowel, the off-glide of the diphthong is doubled as the onset of that next syllable, without being written again. Thus zeyer is pronounced /zey.yer/.

As in Hebrew, five letters have "final" forms, when they occur at the end of a word. These forms do not affect pronunciation at all.

| Initial/Medial | מ | נ | פֿ | צ | כ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final | ם | ן | ף | ץ | ך |

Alphabetical order is alef, alef pasex, alef komac, beys, (veys,) giml, dalet, dalet zayen, dalet zayen šin, hey, vov, gvovayin, šurek, zayen, zayen šin, (xes,) tes, tes šin, yud, yud xirik, gyudayin, gyudayin pasex, vov yud, xof, (xof dageš,) lamed, mem, nun, samex, ayen, pey, fey, cadek, kuf, reyš, (sin,) šin (, tav, sav).

When necessary to avoid confusion, /u/ can be precisely specified with a וּ, called a šurek. /i/ can be invoked as יִ, that is a yud xirek.

Others

Yiddish has many loanwords from Hebrew and Aramaic which are written using the Hebrew abjad in the Semitic way. Weddish, however, writes these words out according to its own orthographic conventions. There are times when it is necessary to use the ancient letters, especially in religious settings.

| Lošn Koydeš Letter | בֿ | ח | כּ | שׂ | ת | תֿ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equivalent | װ | כ | ק | ס | ט | ס |

There is also a highly ornate style of writing Weddish, called xtiv qoydeš ("holy writing", abbr. x"q) where letters are used not as an alphabet, but as an abjad. Vowels may or may not be written in this style. When written, they are written as diacritical marks ("points") around the consonants. In this style, v is written as ו and y as י. Vowels are as follows, with the א written as necessary:

| Standard | X"Q | Roman. |

|---|---|---|

| אַ | אַ | a |

| אָ | אָ | o |

| ע | אֶ | e |

| י | אִ | i |

| ו | אֻ | u |

| ײ | אֵ | ey |

| ײַ | אֱ | ay |

| ױ | אֹ | oy |

| אָו | אֳ | ow |

| אַו | אֲ | aw |

| ø | אְ | /ə/ or syllabic |

Phonotactics

Weddish phonotactics are inherited from Yiddish, which are quite permissive on the world scale[9]. While they do not rise to the level of Georgian or Salish, they are nevertheless difficult for English speakers. Gemination only becomes phonemic across word boundaries. Consonant clusters are spontaneously broken up across syllables in order to make codas less complicated and, if necessary, onsets more so.

Syllabic Consonants

Liquids and fricatives may be said syllabically. Syllabic consonants occur at the end of a word. In an unstressed syllable, syllabic sonorants and syllables with a reduced vowel are indistinguishable. In stressed syllables, no vowel is written, the onset and coda are optional or may consist of a single stop.

Onsets

| Onset Consonant Clusters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | g | d | dz | dž | h | v | z | ž | t | č | y | x | l | m | n | s | p | f | c | k | r | š | ||

| b | bg | bd | by | bl | br | |||||||||||||||||||

| g | gv | gz | gy | gl | gn | gr | ||||||||||||||||||

| d | dv | dz | dy | dl | dn | dr | ||||||||||||||||||

| dz | dzv | dzy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| dž | džy | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| h | hy | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| v | vy | vl | vr | |||||||||||||||||||||

| z | zb | zg | zv | zy | zl | zm | zn | zr | ||||||||||||||||

| ž | žb | žg | žv | žy | žl | žm | ||||||||||||||||||

| t | tv | ty | tx | tl | tm | tn | c | tf | tk | tr | č | |||||||||||||

| č | čv | čy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| y | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | xv | xy | xl | xm | xn | xs | xc | xk | xr | xš | ||||||||||||||

| l | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| m | my | ml | mr | |||||||||||||||||||||

| n | ny | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| s | sd | sv | st | sč | sy | sx | sl | sm | sn | sp | sf | sk | sr | |||||||||||

| p | pv | pt | py | px | pl | pn | ps | pf | pk | pr | pš | |||||||||||||

| f | fy | fl | fr | |||||||||||||||||||||

| c | cd | cv | cy | cl | cn | cr | ||||||||||||||||||

| k | kd | kv | kt | ky | kx | kl | kn | ks | kr | |||||||||||||||

| r | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| š | šv | št | šč | šy | šx | šl | šm | šn | šp | šf | šk | šr | ||||||||||||

There are three-consonant clusters allowed that begin with s or š plus a voiceless stop plus a liquid: spl, spr, str, skr, skl, špl, špr, štr, škl, and škr but not stl or štl.

American's should take care with dr, tr, štr, and str not to "africatize" the cluster.

Codas

Final t's and c's devoice any other code consonants. In writing, it may look like there are therefore combinations not possible on the chart below, but they are pronounced devoiced.

| Coda Consonant Clusters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | g | d | dz | dž | h | v | z | ž | t | č | y | x | l | m | n | s | p | f | c | k | r | š | ||

| b | bd | bdz | bz | bž | ||||||||||||||||||||

| g | gd | gdz | gz | gž | ||||||||||||||||||||

| d | dz | dž | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| dz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| dž | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| h | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| v | vz | vž | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| z | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ž | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| t | tx | c | č | |||||||||||||||||||||

| č | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| y | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | xt | xs | xp | xk | xš | |||||||||||||||||||

| l | lb | lg | ld | ldz | ldž | lv | lz | lž | lt | lč | lx | lm | ln | ls | lp | lf | lc | lk | lš | |||||

| m | mb | md | mdz | mdž | =mdz | =mdž | =mps | mp | =mpf | =mpš | ||||||||||||||

| n | ng | nd | ndz | ndž | =ndz | =ndž | nt | nč | =nkx | =nc | nc | nk | =nč | |||||||||||

| s | st | sč | sp | sc | sk | |||||||||||||||||||

| p | pt | pč | ps | pf | pc | pk | pš | |||||||||||||||||

| f | ft | fč | fs | fp | fc | fk | fš | |||||||||||||||||

| c | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| k | kt | kč | kx | ks | kf | kc | kš | |||||||||||||||||

| r | rb | rg | rd | rdz | rdž | rv | rz | rž | rt | rč | rx | rm | rn | rs | rp | rf | rc | rk | rš | |||||

| š | št | šs | šp | šk | ||||||||||||||||||||

There are also liquids plus stop plus homorganic, alveolar fricative: lps, lbz, lks, lgz, rps, rbz, rks, rgz.

Suprasegmentals

Stress is predicable, if one knows the root of a word. The first syllable of the root receives primary stress, with secondary stresses proceeding out like ripples on a pond to every other syllable, forwards and backwards. (The major exception is the dual, which moves the stress of a word with an odd number of syllables.) The default rhythm of Weddish is trochaic: stressed-unstressed. Neither vowel length nor stress is phonemic. Long vowels indicate stress. If the word is long, one of the first three syllables must have primary stress. Prefixes and suffixes all have an underlying vowel which is expressed or repressed in order to maintain the rhythm pattern. Two syllables with reduced vowels may not follow each other. Polar and interrogative questions are both marked by a rising tone at the end of the utterance.

Syntax

| Weddish וועדיש | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progress: 43% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| fusional | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alignment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ergative-Absolutive | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head direction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Initial | Mixed | Final | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Primary word order | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Subject-verb-object | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tonal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Declensions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conjugations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Genders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Verbs conjugate according to... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Voice | Mood | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Person | Number | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tense | Aspect | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Weddish aims to appeal to English speakers. While the verbal-system is somewhat new, the noun-system should be easy. Nouns are not inflected, but pronouns do have unique forms that show what part of speech they can be. Like German, however, articles do inflect. Like Hebrew, there are two noun genders. The masculine is most often animate, while the feminine is not. Adjectives do not inflect unless substantive.

Purposefully chosen to stimulate thinking, Weddish has an ergative-absolutive morphosyntactic alignment. Most languages in the world consider the actor of transitive verb and the subject of an intransitive verb to be equivalent. The object of a transitive verb is special in these systems. It can be promoted to the subject via the passive voice. Normally, it must come after the verb. Weddish treats the object of a transitive verb and the subject of a transitive verb the same, called the "absolutive case". Actors of transitive verbs are specially in Weddish, called the "ergative case".

It would be tempting to classify Weddish as VSO (subject-veb-object) like Hebrew, but that's not quite right. It is, in fact, a V2 language, which means the verb always wants to come second. (Discourse particles and few other things do not count towards calculating where "second" is, and entire phrases are taken as a whole when counting this place.) Because core cases are marked almost solely by word order, the actor of a transitive verb (the ergative case) must come before the verb, i.e. first in the sentence.

The V2 Principle is carried throughout Weddish, to the point where it might be labeled a "head second" language. This is not a recognized typology, since languages are either head-initial, head-final, or mixed. In compound nouns, the head is second. For auxiliary verbs, the head verb is second. For nouns with attributive modifiers, the article comes first, but adjectives come after the noun, making it head-second as well.

Number

English, Hebrew, Yiddish and many other languages have two numbers: singular and plural. Weddish (like Arabic) has three: singular, dual, and plural. Obviously, the dual is for two of something, and the plural therefore means three or more. However, in regards to persons, the dual is used on married people, even if only one of them is being spoken about. Exceptions can be made in every case except the ergative, which is reserved for the spouses to use on each other. This distinction does not apply in the third person for people not present.

Weddish also distinguishes whether actions were done as individuals or all as a group. It also possible to add "associates" of a noun to it.

Copula

The verb "to be", "to become", and "to have" are all copulas in Weddish. That means they all use only the absolutive case, never the ergative. However, "to be" and "to have" are more like "to equal" and "to exist". "I have shoes" is literally "Shoes exist to me". This can be easier for Far East Asians to learn than Westerners.

Morphology

Case

| Genitive | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| פֿון/fun | |||

| Dative | Ablative | Partitive | Equative |

| ל־/l- | ב־/b- | מ־/m- | ק־/k- |

By default, all nouns are in the absolutive case. But, if they are placed before the verb, then they are said to be in the ergative case, though their morphology is unchanged. The only exception is the masculine singular/dual definite article changes in the ergative case. Linguists call these two case the "core cases" of a language, since they are fundamental. There are five additional cases --- called "non-core" cases --- in Weddish that are also very important. Unlike many languages that have suffixing case marking, Weddish has prefixing. This is because they are derived from Hebrew Inseparable Prepositions (IP's). Phrases in the non-core cases either relate to the verb (and are hence, adverbial), or are in a noun phrase. In relation to nouns, the core cases are all seen as greater specificity within the genitive case.

Non-core cases all fall under the umbrella term "genitive". The generic genitive is not a case per se, but a preposition (meaning, a separable preposition). An expression like dos line fun gelt/the love of money is even more ambiguous in Weddish than in English. It may mean the love belonging to money, the love in/by money, the love from/composed of money, or the love as/according to money. After a genitive phrase has been established or is implicitly understood, the phrase may be into a compound noun using the "head-second" structure.

| Definite | Indefinite | Anarthrous | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m.sg/dl | f.sg/dl | n/pl | sg/dl | ||

| Erg. | der | dos | di | a(n) | ø |

| Abs. | dem | ||||

| Dat. | lem | ler | li | lawn | l- |

| Abl. | bem | bos | bi | bawm | b- |

| Part. | mem | mos | mi | mawm | m-/min |

| Eq. | kem | kos | ki | kawm | k- |

The definite article is always determined. In the following hierarchy, if an article is any of these, it is also all those to the left:

- Identifying --> Anaphoric --> Well-Known --> Par Excellence --> Monadic

Number

Weddish verbs conjugate for three numbers (singular, dual, and plural), but nouns inflect eleven different ways! However, these myriad ways can be easily understood as the optional adding of "associates" to a noun, and distinguishing between masses of individuals and collectives (one forest vs. many trees). The following table is color-coded to show verb conjugation in the singular (light background), dual (purple), and plural (brown).

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distributive | פֿרײַנד fraynd a friend |

פֿרינדײַים frindayim two friends each |

פֿרײַנדין frayndin friends each |

| Collective | געפֿרינדײַים gefrindayim a couple of friends |

געפֿרײַנדין gefrayndin a group of friends | |

| Distributive Associative |

פֿרײַנדז frayndz a friend and associates each |

פֿרינדײַיםז frindayimz two friends and associates each |

פֿרײַנדינז frayndinz friends and associates each |

| Collective Associative |

געפֿרײַנז gefrayndz a group of a friend and associates |

געפרינדײַימז gefrindayimz a group of two friends and associates |

געפֿרײַנדינז gefrayndinz a group of friends and associates |

The dual ending is unique, in that is shifts the accent pattern of the root to itself. It may be written -áyim to indicate that shift. This shift triggers vowel reduction of of the previous syllable, if it is a diphthong (cutting it down to its first vowel).

Forms lacking the collective plural endings are automatically distributive.

Pronouns

Independent Personal

Absolutive independent personal pronouns are most commonly used with ø-copula clauses to show predication. Such sentences are distinguished from those with the "to be" verb, which show absolute identity, as opposed to mere attribution. Gu Yidiš/We are Jewish vs. Big Džonzez/We are (the) Jones's.

| Ergative | Absolutive | Dative | Ablative | Partitive | Equative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | sg | ix | mix | mir | bix | mix | kix |

| dl | nanxu | gu | gir | bug | ming | kowg | |

| pl | undz | mir | undz | bu | minu | ku | |

| 2 | sg | du | dix | dir | bed | mind | ked |

| dl | stu | stuk | stire | bist | minst | kist | |

| pl | ir | ayx | ayx | bikm | mint | kat | |

| 3 | m.sg | er | 'im | inen | bo | mino | ko |

| f.sg | zi | es | aya | ba | mina | ka | |

| dl | bera | hura | hav | bav | minav | 'kav | |

| n/pl | zey | cey | čire | bouč | minč | kač | |

Interrogative

| Erg. | Abs. | Gen. | Dat. | Abl. | Part. | Eq. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons. | mi | ver | vermenc | vermen | bimi | mimi | komi |

| Impers. | ma | vos | fun vos | vu | vi | vat | ven |

The interrogative pronouns do not inflect for person, number, or gender. Linguists would say they are animate and inanimate, though Weddish grammar calls them "personal" and "impersonal". They are identical to the relative pronoun (just as in English) and must match their antecedent in animacy, but not in case. Instead (just as in English) they indicate their new role in the relative clause.

Affixes

Like Hebrew, Weddish uses enclitic forms of pronouns to indicate several things. On verbs, pronominal suffixes mark the absolutive argument of the clause. On nouns, they mark a genitive relationship. Pronominal prefixes are used exclusively on transitive verbs to mark the ergative argument, and are obligatory. Weddish is not pro-drop, and an affix on both ends is required on transitive verbs. Remember, there are no ambi-transitive verbs in Weddish. Use of the independent personal pronouns when the person has been specified on either end of the verb is considered emphatic.

| Person | # | Suffix | Prefix |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | sg | -(n)i | ni- |

| dl | -(u)g | gu- | |

| pl | -(n)u | na- | |

| 2 | sg | -(e)d | de- |

| dl | -(e)st | sti- | |

| pl | -ti | ta- | |

| 3 | m.sg | -o | ro- |

| f.sg | -a | ya- | |

| dl | -av* | ø | |

| n/pl | -(ay/i)č | čay- |

Verbs

Weddish verbs do not conjugate for tense, only aspect.

Aspect Ablaut

| Perfective | Imperfective |

|---|---|

| -ei- | -i- |

| -au- | -ai- |

| -ou- | -u- |

| -e- | -a- |

| -o- | -oi- |

Voices

- Causative: š/že-

- Reflexive: hit/hid-

- Antipassive: V-u

- Mixed

Non-finite

- participle -ing

- infinitive absolute: u-V

- infinitive construct: ge-

Incorporation

On the Mithun scale[10], Weddish does type-I and type-II noun incorporation. This means 1) I picked berries -> I berry-picked, and 2) I washed his face -> I face-washed him.

Derivation

Compounding

When the relationships between nouns is genitive, and it has already been stated or can easily be implied, compound nouns may be formed. For example, a field for football/soccer may become fusbolfeld. (Note the loss of abstraction suffixes.) Suppose it was an Australian rules football field. Would could make fusbolfeldeoystralie. Lastly, If one wanted to add that it is mgroz/composed of grass, this could become פֿוסבאָלפֿעלדעאויסטראליעגראָז/fusbolfeldeoystraliegroz. Words with greater than four parts are deemed colloquial. Word order is "head second", with the first specifier coming at the very front.

Abstract Nouns

All nouns in Weddish are inherently concrete. Two levels of abstraction are possible through suffixation. The first signifies the practice of one or more persons. The second signifies the understanding of the practice. Both are available in both genders, with the masculine form referring to a person (of either gender), however, the "practice"-form occurs much more often in the masculine and the "understanding"-form occurs much more often in the feminine. Remember, this are no truly abstract nouns in Weddish, for they do not exist.

| Suffix | "Tennis" | gloss | "Peace" | gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ø | a tennis | a game of tennis | a šolem | a season of peace |

| -ay | dos tenisayo | his tennis game | šolemaya | her (practice of) peace |

| dem tenisayt | the tennis player | dem šolemayt | the peacemaker | |

| -šaft | dos tenisšafte | the game of tennis / "tennisology" | šolemšafte | peace know-how |

| a tenisšaft | a tennisologist | a šolemšaft | a student of peace |

Discourse

Formality

Particles

By far the most commonly occurring particle is v-, which is like a verbal comma. Yiddish - like English - has the word and/un. Weddish, however, only uses that word to connect clauses. v- is a return to Hebrew, though typically not at the start of sentences.

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/1

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/2

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/3

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/4

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/11

- ^ As in Hebrew, uvular may be seen as the most prestigious form: http://wals.info/chapter/6

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/9

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/19

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/12

- ^ Mithun, Marianne. 1984. The Evolution of Noun Incorporation. Language, Vol. 60, No. 4. pp. 847-894.