Luthic

This article is private. The author requests that you do not make changes to this project without approval. By all means, please help fix spelling, grammar and organisation problems, thank you. |

| Luthic | |

|---|---|

| Lûthica | |

Flag of the Luthic-speaking Ravenna | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ] |

| Created by | Lëtzelúcia |

| Date | 2023 |

| Setting | Alternative history Italy |

| Native to | Ravenna; Ferrara and Bologna |

| Ethnicity | Luths |

| Native speakers | 149,500 (2020) |

Indo-European

| |

Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | Italy (recognised by the Luthic Community of Ravenna) |

| Regulated by | Council for the Luthic Language |

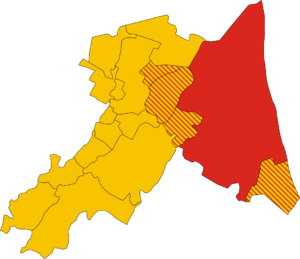

The areas where Luthic (red and orange) is spoken. | |

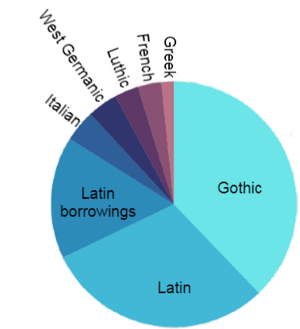

Luthic (/ˈluːθ.ɪk/ LOOTH-ik, less often /ˈlʌθ.ɪk/ LUTH-ik, also Luthish; endonym: Lûthica [ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ] or Rasda Lûthica [ˈʁaz.dɐ ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ]) is an Italic language that is spoken by the Luths, with strong East Germanic influence. Unlike other Romance languages, such as Portuguese, Spanish, Catalan, Occitan and French, Luthic has a large inherited vocabulary from East Germanic, instead of only proper names that survived in historical accounts, and loanwords. About 250,000 people speak Luthic worldwide.

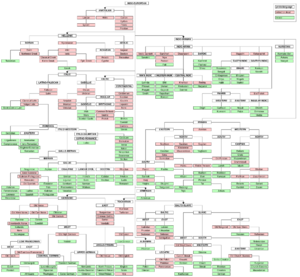

Luthic is the result of a prolonged contact among members of both regions after the Gothic raids towards the Roman Empire began, together with the later West Germanic merchants’ travels to and from the Western Roman Empire. These connections, the interactions between the Papal States and the conquest by the Germanic dynasties of the Roman Empire slowly formed a creole as a lingua franca for mutual communication.

As a standard form of the Gotho-Romance language, Luthic has similarities with other Italo-Dalmatian languages, Western Romance languages and Sardinian. The status of Luthic as the regional language of Ravenna and the existence there of a regulatory body have removed Luthic, at least in part, from the domain of Standard Italian, its traditional Dachsprache. It is also related to the Florentine dialect spoken by the Italians in the Italian city of Florence and its immediate surroundings.

Luthic is an inflected fusional language, with four cases for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative); three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter); and two numbers (singular, plural).

Classification

Luthic is an Indo-European language that belongs to the Gotho-Romance group of the Italic languages, however Luthic has great Germanic influence; where the Germanic languages are traditionally subdivided into three branches: North Germanic, East Germanic, and West Germanic. The first of these branches survives in modern Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Elfdalian, Faroese, and Icelandic, all of which are descended from Old Norse. The East Germanic languages are now extinct, and Gothic is the only language in this branch which survives in written texts; Luthic is the only surviving Indo-European language with extensive East Germanic derived vocabulary. The West Germanic languages, however, have undergone extensive dialectal subdivision and are now represented in modern languages such as English, German, Dutch, Yiddish, Afrikaans, and others.

Among the Romance languages, its classification has always been controversial, for example, it is one of the Italo-Dalmatian languages and most closely related to Istriot on the one hand and Tuscan-Italian on the other. Some authors include it among the Gallo-Italic languages, and according to others, it is not related to either one. Although both Ethnologue and Glottolog group Luthic into a new language group, the Gotho-Romance (opere citato) family is still somewhat dubious.

Luthic has been influenced by Italian, Frankish, Gothic and Langobardic since its first attestation, the great influence of these languages on the vocabulary and grammar of Modern Luthic is widely acknowledged. Most specialists in language contact do consider Luthic to be a true mixed language. Luthic is classified as a Romance langauge because it shares innovations with other Romance languages such as Italian, French and Spanish.

| Biblical Gothic | Crimean Gothic¹ | Luthic | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| ahtau /ˈax.tɔː/ | athe /ˈa.te/ | attau [ˈat.tɔ] | eight |

| baur /bɔr/ barn /barn/ |

baar /bar/ *ba(a)rn /barn/? |

baure [ˈbɔ.ɾe] barnȯ [ˈbaɾ.no] |

child |

| brōþar /ˈbroː.θar/ | bruder /'bru.der/ | broþar [ˈbɾo.θɐr] | brother |

| wair /wɛr/ | fers /fers/ | vaere [ˈvɛ.re] | wer- |

| handus /ˈhan.dus/ | handa /ˈan.da/ | hando [ˈhan.du] (archaic or obsolete) | hand |

| haubiþ /ˈhɔː.βiθ/ | hoef (for *hoeft) /oft/ | hauviþȯ [ˈhɔ.vi.θo] (archaic or obsolete) | head |

| qiman /ˈkʷi.man/ | kommen /'ko.men/ | qemare [kᶣeˈma.ɾe] | to come |

| hlahjan /'hlax.jan/ | lachen /'la.xen/ (/'la.ɣen/?) | clahare [klɐˈha.ɾe] | to laugh |

| augō /ˈɔː.ɣoː/ | oeghene /ˈo.ɣe.ne/ | augonȯ [ˈɔ.ɣ˕o.no] | eye |

- ¹ Discussions cover the different versions of Busbecq’s report, including scribal emendation and errors in printing and subsequent corrections. It seems that Busbecq’s understanding and documentation of Crimean Gothic were influenced by his Flemish background and possibly by German. He obtained his information from a Crimean Greek source who was knowledgeable in Crimean Gothic. The individual from Crimea who supplied the language information was either originally Greek or fluent in Crimean Gothic but more proficient in Greek than their own native language. In both cases, it’s likely that the pronunciation of Crimean Gothic words was influenced to some extent by the phonetics of the Greek language spoken in that area and time.

History

The Luthic philologist Aþalphonso Silva divided the history of Luthic into a period from 500 AD to 1740 to be “Mediaeval Luthic”, which he subdivided into “Gothic Luthic” (500–1100), “Mediaeval Luthic” (1100–1600) and “late Mediaeval Luthic” (1600–1740).

An additional period was later created by Lucia Giamane, from c. 325 AD to 500 AD to be called “Proto-Luthic”, which she believes to be an Vulgar Latin ethnolect, spoken by the early Goths during its period of co-existence with the Roman Empire, no written records from such an early period survive, and if any ever existed, it was fully lost during the Gothic War (376–382) and during the Sack of Rome (410). Proto-Luthic ultimately is the result of the Romano-Germanic culture.

The term Romano-Germanic describes the conflation of Roman culture with that of various Germanic peoples in areas successively ruled by the Roman Empire and Germanic “barbarian monarchies”. These include the kingdoms of the Visigoths (in Hispania and Gallia Narbonensis), the Ostrogoths (in Italia, Sicilia, Raetia, Noricum, Pannonia, Dalmatia and Dacia), the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in Sub-Roman Britain, and finally the Franks who established the nucleus of the later “Holy Roman Empire” in Gallia Aquitania, Gallia Lugdunensis, Gallia Belgica, Germania Superior and Inferior, and parts of the previously unconquered Germania Magna. Additionally, minor Germanic tribes – the Vandals, the Suebi, the Burgundians, the Alemanni, and later the Lombards − also established their kingdoms in Roman territory in the West.

Romano-Germanic cultural contact begins as early as the first Roman accounts of the Germanic peoples. Roman influence is perceptible beyond the boundaries of the empire, in the Northern European Roman Iron Age of the first centuries AD. The nature of this cultural contact changes with the decline of the Roman Empire and the beginning Migration period in the wake of the crisis of the third century: the “barbarian” peoples of Germania Magna formerly known as mercenaries and traders now came as invaders and eventually as a new ruling elite, even in Italy itself, beginning with Odoacer’s rise to the rank of Dux Italiae in 476 AD.

The cultural syncretism was most pronounced in Francia. In West Francia, the nucleus of what was to become France, the Frankish language was eventually extinct, but not without leaving significant traces in the emerging Romance language. In East Francia on the other hand, the nucleus of what was to become the kingdom of Germany and ultimately German-speaking Europe, the syncretism was less pronounced since only its southernmost portion had ever been part of the Roman Empire, as Germania Superior: all territories on the right hand side of the Rhine remain Germanic-speaking. Those parts of the Germanic sphere extends along the left of the Rhine, including the Swiss plateau, the Alsace, the Rhineland and Flanders, are the parts where Romano-Germanic cultural contact remains most evident.

Early Germanic law reflects the coexistence of Roman and Germanic cultures during the Migration period in applying separate laws to Roman and Germanic individuals, notably the Lex Romana Visigothorum (506), the Lex Romana Curiensis and the Lex Romana Burgundionum. The separate cultures amalgamated after Christianisation, and by the Carolingian period the distinction of Roman vs. Germanic subjects had been replaced by the feudal system of the Three Estates of the Realm.

With a renewed close attention to the history and literature of ancient Rome in the 12th century, the mediaeval aristocracy saw itself mirrored in the accounts of ancient Roman nobility. Some made doubtful claims to direct descent from Roman aristocracy. In the 19th century, German, Luth and French mediaevalists worried about the origins of the great mediaeval families. Did the great families descend from the aristocracy of the Roman Empire or from the barbarian chieftains who invaded the Roman Empire between 400 and 600? Did the families originate in the Latin or Germanic world? Both, it seems. Mediaeval Western Europe was an amalgam of Roman and ‘Barbarian’ bloodlines. The cultural and genetic influence of the Visigoths, Franks, et al. is readily apparent in the socio-cultural and political framework of Mediaeval Europe. In spite of this, the legacy of Rome, both social-cultural and genetic pervaded every aspect of Mediaeval society – this was of course greatly assisted by the mediaeval Church.

The initial trouble for the later Roman Empire came from East Germanic speakers, with various tribal groups such as the Vandals and Burgundians traversing Europe. However, it was the Goths who notably contributed to the linguistic record of the East Germanic languages. Originating from the lower Vistula, they migrated to present-day Ukraine. Later, facing pressure from the Huns, they moved into the Balkans and eventually into Western Europe. Among them, the Visigoths settled in Spain, shaping its post-Roman state, while the Ostrogoths became custodians of the last Roman emperors in Italy. By the eighth century, linguistic assimilation into Romance-speaking populations had largely absorbed the Goths of Spain and Italy. Wulfila, a prominent Christian missionary and later bishop of the Visigoths, translated the Bible into Gothic while they resided in the northeast Balkans, providing a significant linguistic record of Gothic and East Germanic. A small group of Ostrogoths left in Crimea resurfaced in the sixteenth century through a wordlist compiled by Ogier de Busbecq, the Holy Roman Emperor’s ambassador to the Sublime Porte. However, these Crimean Gothic speakers disappeared linguistically shortly after Busbecq documented their vocabulary.

Gothic Luthic

The earliest varieties of a Luthic language, collectively known as Gothic Luthic or “Gotho-Luthic”, evolved from the contact of Latin dialects and East Germanic languages. A considerable amount of East Germanic vocabulary was incorporated into Luthic over some five centuries. Approximately 1,200 uncompounded Luthic words are derived from Gothic and ultimately from Proto-Indo-European. Of these 1,200, 700 are nouns, 300 are verbs and 200 are adjectives. Luthic has also absorbed many loanwords, most of which were borrowed from West Germanic languages of the Early Middle Ages.

Only a few documents in Gothic Luthic have survived – not enough for a complete reconstruction of the language. Most Gothic Luthic-language sources are translations or glosses of other languages (namely, Greek and Latin), so foreign linguistic elements most certainly influenced the texts. Nevertheless, Gothic Luthic was probably very close to Gothic (it is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text corpus). These are the primary sources:

- Codex Luthicus (Ravenna), two parts: 87 leaves

- It contains scattered passages from the New Testament (including parts of the gospels and the Epistles), from the Old Testament (Nehemiah), and some commentaries. The text likely had been somewhat modified by copyists. It was written using the Gothic alphabet, an alphabet used for writing the Gothic language. It was developed in the 4th century AD by Ulfilas (or Wulfila), a Gothic preacher of Cappadocian Greek descent, for the purpose of translating the Bible.

- Codex Ravennas (Ravenna), four parts: 140 leaves

- A civil code enacted under Theodoric the Great. The code covered the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy, but mainly Ravenna, as Theodoric devoted most of his architectural attention to his capital, Ravenna. Codex Ravennas was also written using the Gothic alphabet. The text likely had been somewhat modified by copyists. Together with four leaves, fragments of Romans 11–15 (a Luthic–Latin diglot).

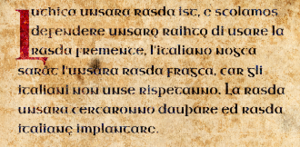

Mediaeval Luthic

In the mediaeval period, Luthic emerged as a separate language from Gothic. The main written language was Latin, and the few Luthic-language texts preserved from this period are written in the Latin alphabet. From the 7th to the 16th centuries, Mediaeval Luthic gradually transformed through language contact with Old Italian, Langobardic and Frankish. During the Carolingian Empire (773–774), Charles conquered the Lombards and thus included northern Italy in his sphere of influence. He renewed the Vatican donation and the promise to the papacy of continued Frankish protection. Frankish was very strong, until Louis’ eldest surviving son Lothair I became Emperor in name but de facto only the ruler of the Middle Frankish Kingdom.

After the fall of Middle Francia and the rise of Holy Roman Empire, Louis II conquered Bari in 871 led to poor relations with the Eastern Roman Empire, which led to a lesser degree of the Greek influence present in Luthic.

English: “Luthic is our language, and we must defend our right to use it freely, Italian will never be our language, as the Italians don’t respect us”

Late Mediaeval Luthic

Fraugiani e Narri hanno rasda fre.

“Lords and jesters have free speech.”

Following the first Bible translation, the development of Luthic as a written language, as a language of religion, administration, and public discourse accelerated. In the second half of the 17th century, grammarians elaborated grammars of Luthic, first among them Þiudareico Bianchi’s 1657 Latin grammar De studio linguæ luthicæ.

De Studio Linguæ Luthicæ

De Studio Linguæ Luthicæ (English: On Study of the Luthic Language) often referred to as simply the Luthicæ (/lʌˈθiˌki, lʌθˈaɪˌki/ lu-THEE-KEE), is a book by Þiudareico Bianchi that expounds Luthic grammar. The Luthicæ is written in Latin and comprises two volumes, and was first published on 9 September 1657.

Book 1, De grammatica

Book 1, subtitled De grammatica (On grammar) concerns fundamental grammar features present in Luthic. It opens a collection of examples and Luthic–Latin diglot lemmata.

Book 2, De orthographia

Book 2, subtitled De orthographia (On orthography), is an exposition of the many vernacular orthographies Luthic had, and eventual suggestions for a universal orthography.

Etymology

The name of the Luths is hugely linked to the name of the Goths, itself one of the most discussed topics in Germanic philology. The autonym is attested as 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰 (gutþiuda) (the status of this word as a Gothic autonym prior to the Ostrogothic period is disputed) on the Gothic calendar (in the Codex Ambrosianus A): þize ana gutþiudai managaize marwtre jah friþareikeikeis. However, on the basis of parallel formations in Germanic (svíþjóð; angelþēod) and non-Germanic (Old Irish cruithen-tuath) indicates that it means “land of the Goths, Gothia”, instead of a more literal translation “Gothpeople”. The first element however may be also the same element attested on the Ring of Pietrossa ᚷᚢᛏᚨᚾᛁ (gutanī). Roman authors of late antiquity did not classify the Goths as Germani. While the Gutones, the Pomeranian precursors of the Goths, and the Vandili, the Silesian ancestors of the Vandals, were still considered part of Tacitean Germania, the later Goths, Vandals, and other East Germanic tribes were differentiated from the Germans and were referred to as Scythians, Goths, or some other special names. The sole exception are the Burgundians, who were considered German because they came to Gaul via Germania. In keeping with this classification, post-Tacitean Scandinavians were also no longer counted among the Germans, even though they were regarded as close relatives. The word for Luthic is first attested as 𐌻𐌿𐌸𐌹𐌺𐍃 (luþiks) on the Codex Luthicus, named after so. The name was probably first recorded via Greco-Roman writers, as *Luthae, a formation similar to Getae, itself derived from *leuhtą. Ultimately meaning the lighters. 𐌻𐌿𐌸𐌹𐌺𐍃 is probably a corruption *leuhtą, *leuthą, *Luthae, influenced by gothus, then reborrowed via a Germanic language, where *-th- > -þ-.

Geographical distribution

Luthic is spoken mainly in Emilia-Romagna, Italy, where it is primarily spoken in Ravenna and its adjacent communes. Although Luthic is spoken almost exclusively in Emilia-Romagna, it has also been spoken outside of Italy. Luth and general Italian emigrant communities (the largest of which are to be found in the Americas) sometimes employ Luthic as their primary language. The largest concentrations of Luthic speakers are found in the provinces of Ravenna, Ferrara and Bologna (Metropolitan City of Bologna). The people of Ravenna live in tetraglossia, as Romagnol, Emilian and Italian are spoken in those provinces alongside Luthic.

According to a census by ISTAT (The Italian National Institute of Statistics), Luthic is spoken by an estimated 250,000 people, however only 149,500 are considered de facto natives, and approximately 50,000 are monolinguals.

Status and usage

As in most European countries, the minority languages are defined by legislation or constitutional documents and afforded some form of official support. In 1992, the Council of Europe adopted the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages to protect and promote historical regional and minority languages in Europe.

Luthic is regulated by the Council for the Luthic Language (Luthic: Gafaurdo faul·la Rasda Lûthica [ɡɐˈfɔɾ.du fɔl‿lɐ ˈʁaz.dɐ ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ]) and the Luthic Community of Ravenna (Luthic: Gamaenescape Lûthica Ravennae [ɡɐˌmɛ.neˈska.fe ˈlu.tʰi.xɐ ʁɐˈvẽ.nɛ]). The existence of a regulatory body has removed Luthic, at least in part, from the domain of Standard Italian, its traditional Dachsprache, Luthic was considered an Italian dialect like many others until about World War II, but then it underwent ausbau.

Diglossia and code-switching

Luthic is recognised as a minor language in Ravenna. Italy’s official language is Italian, as stated by the framework law no. 482/1999 and Trentino Alto-Adige’s special Statute, which is adopted with a constitutional law. Around the world there are an estimated 64 million native Italian speakers and another 21 million who use it as a second language. Italian is often natively spoken in a regional variety, not to be confused with Italy’s regional and minority languages; however, the establishment of a national education system led to a decrease in variation in the languages spoken across the country during the 20th century. Standardisation was further expanded in the 1950s and 1960s due to economic growth and the rise of mass media and television (the state broadcaster RAI helped set a standard Italian).

Code-switching between Luthic, Emilian dialects and Italian is frequent among Luthic speakers, in both informal and formal settings (such as on television).

Education

Education in Italy is free and mandatory from ages six to sixteen, and consists of five stages: kindergarten (scuola dell’infanzia), primary school (scuola primaria), lower secondary school (scuola secondaria di primo grado), upper secondary school (scuola secondaria di secondo grado), and university (università). Although mostly in Italian, education is Luthic has been implemented in 2018 by Ravenna University. In 2018, the Italian secondary education was evaluated as below the OECD average. Italy scored below the OECD average in reading and science, and near OECD average in mathematics. Mean performance in Italy declined in reading and science, and remained stable in mathematics. Trento and Bolzano scored at an above the national average in reading. Compared to school children in other OECD countries, children in Italy missed out on a greater amount of learning due to absences and indiscipline in classrooms. A wide gap exists between northern schools, which perform near average, and schools in the South, that had much poorer results. The 2018 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study ranks children in Italy 16th for reading. Compared to school children in other OECD countries, children in Italy missed out on a greater amount of learning due to absences and indiscipline in classrooms.

Most of the Luths also speak Italian, this is commoner for Luth elders, and most of the Luth elders may speak only Italian because of the influence from the Fascist period, as the Fascist government endorsed a stringent education policy in Italy aiming at eliminating illiteracy, which was a serious problem in Italy at the time, as well as improving the allegiance of Italians to the state. The Fascist government’s first minister of education from 1922 to 1924 Giovanni Gentile recommended that education policy should focus on indoctrination of students into Fascism and to educate youth to respect and be obedient to authority. In 1929, education policy took a major step towards being completely taken over by the agenda of indoctrination.> In that year, the Fascist government took control of the authorization of all textbooks, all secondary school teachers were required to take an oath of loyalty to Fascism and children began to be taught that they owed the same loyalty to Fascism as they did to God. In 1933, all university teachers were required to be members of the National Fascist Party. From the 1930s to 1940s, Italy’s education focused on the history of Italy displaying Italy as a force of civilization during the Roman era, displaying the rebirth of Italian nationalism and the struggle for Italian independence and unity during the Risorgimento. In the late 1930s, the Fascist government copied Nazi Germany’s education system on the issue of physical fitness and began an agenda that demanded that Italians become physically healthy. Intellectual talent in Italy was rewarded and promoted by the Fascist government through the Royal Academy of Italy which was created in 1926 to promote and coordinate Italy’s intellectual activity.

Films and music

Most films and songs are in vernacular Italian, Luthic is seldom spoken in television and radio. Some educational shows hosted by the Luthic Community of Ravenna and Ravenna University are often in Standard Luthic.

Written media

Luthic is mostly found as written media, However newspapers usually use Italian and reserve Luthic for sarcastic commentaries and caricatures. Headlines in Luthic are common. The letter to the editor section often includes entire paragraphs in Luthic. Many newspapers also regularly publish personal columns in Luthic. Most comedies are written in Luthic. Comic books are often written in Luthic instead of Italian. In novels and short stories, most of the Luth authors, write the dialogues in their Luthic dialects.

Luthic regarded as an Italian dialect

Luthic lexicon is discrepant from those of other Romance languages, since most of the words present in Modern Luthic are ultimately of Germanic origin. The lexical differentiation was a big factor for the creation of an independent regulatory body. There were many attempts to assimilate Luthic into the Italian dialect continuum, as in recent centuries, the intermediate dialects between the major Romance languages have been moving toward extinction, as their speakers have switched to varieties closer to the more prestigious national standards. That has been most notable in France, owing to the French government’s refusal to recognise minority languages. For many decades since Italy’s unification, the attitude of the French government towards the ethnolinguistic minorities was copied by the Italian government. A movement called “Italianised Luthic Movement” (Luthic: Movimento Lûthicae Italianegiatae; Italian: Movimento per il Lutico Italianeggiato) tried to italianase Luthic’s vocabulary and reduce the inherited Germanic vocabulary, in order to assimilate Luthic as an Italian derived language; modern Luthic orthography was affected by this movement.

Almost all of the Romance languages spoken in Italy are native to the area in which they are spoken. Apart from Standard Italian, these languages are often referred to as dialetti “dialects”, both colloquially and in scholarly usage; however, the term may coexist with other labels like “minority languages” or “vernaculars” for some of them. Italian was first declared to be Italy's official language during the Fascist period, more specifically through the R.D.l., adopted on 15 October 1925, with the name of Sull'Obbligo della lingua italiana in tutti gli uffici giudiziari del Regno, salvo le eccezioni stabilite nei trattati internazionali per la città di Fiume. According to UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, there are 31 endangered languages in Italy.

Standard Luthic

The basis of Standard Luthic was developed by the popular language spoken by the Ravennese people, whose was highly influenced by Gothic, together with other East Germanic substrate, such as Vandalic and Burgundian and other ancient West Germanic languages, mainly Frankish and Langobardic. Standard Luthic orthography was further influenced by Italian. Increasing mobility of the population and the dissemination of the language through mass media such as radio and television are leading to a gradual standardisation towards a “Standard Luthic” through the process of koineization.

Alphabet

Luthic has a shallow orthography, meaning very regular spelling with an almost one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds. In linguistic terms, the writing system is close to being a phonemic orthography. The most important of the few exceptions are the following (see below for more details):

- The letter c represents the sound /k/ at the end of words and before the letters a, o, and u but represents the sound /t͡ʃ/ before the letters e and i.

- The letter g represents the sound /ɡ/ at the end of words and before the letters a, o, and u but represents the sound /d͡ʒ/ before the letters e and i. It also represents the sound /ŋ/ before c, q or g.

- The letter r represents the sound /ʁ/ onset or stressed intervocalic, /ɾ/ when intervocalic or nearby another consonant or at the end of words and /ʀ/ if doubled.

- The cluster sc /sk/ before the letters e and i represents the sound /ʃ/, geminate if intervocalic.

- The spellings ci and gi before another vowel represent only /t͡ʃ/ or /d͡ʒ/ with no /i/ ~ /j/ sound.

- Unless c or g precede stressed /i/ (pharmacia /pʰɐɾ.mɐˈtʃi.ɐ/ ‘pharmacy’, biologia /bjo.loˈdʒi.ɐ/ ‘biology’), these may be optionally spelt as cï and gï' (pharmacïa, biologïa).

- The spelling qu and gu always represent the sounds /k/ and /ɡ/.

- The spelling ġl and ġn represent the palatals /ʎ/ and /ɲ/ retrospectively; always geminate if intervocalic.

The Luthic alphabet is considered to consist of 22 letters; j, k, w, x, y are excluded, and often avoided in loanwords, as tacċi vs taxi, cċenophobo vs xenofobo, geins vs jeans, Giorque vs York, Valsar vs Walsar:

- The circumflex accent is used over vowels to indicate irregular stress.

- The digraphs ⟨ae, au, ei⟩ are used to indicate stressed /ɛ ɔ i/ retrospectively.

- In VCC structures and some Italian borrowings, the digraphs are not found.

- The overdot accent is used to over ⟨a, o⟩ to indicate coda /a o/.

- The letter o always represents the sound /u/ in coda.

- The overdot is also used over ⟨c, g⟩ to indicate palatalisation.

- The diaeresis accent is used to distinguish from a digraph or a diphthong.

- The letter ⟨s⟩ can symbolise voiced or voiceless consonants. ⟨s⟩ symbolises /s/ onset before a vowel, when clustered with a voiceless consonant (⟨p, f, c, q⟩), and when doubled (geminate); it symbolises /z/ when between vowels and when clustered with voiced consonants.

| Letter | Name | Historical name | IPA | Diacritics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A, a | a [ˈa] | asga [ˈaz.ɡɐ] | /ɐ/ or /a/ | â, ȧ |

| B, b | bi [bi] | baerca [ˈbɛɾ.kɐ] | /b/ or /ʋ/ | — |

| C, c | ci [ˈt͡ʃi] | caunȯ [ˈkɔ.no] | /k/, /t͡ʃ/ or /x/ | ċ |

| D, d | di [ˈdi] | dago [ˈda.ɣ˕u] | /d/ or /ð̞/ | — |

| E, e | e [ˈɛ] | aeqqo [ˈɛk.kʷu] | /e/ or /ɛ/ | ê |

| F, f | effe [ˈɛf.fe] | faeho [ˈfɛ.hu] | /f/ or /p͡f/ | — |

| G, g | gi [ˈd͡ʒi] | geva [ˈd͡ʒe.vɐ] | /ɡ/, /d͡ʒ/, /ɣ˕/ or /ŋ/ | ġ |

| H, h | acca [ˈak.kɐ] | haġlo [ˈhaʎ.ʎu] | /h/ or /ç/ | — |

| I, i | i [ˈi] | eisso [ˈis.su] | /i/ or /j/ | ï |

| L, l | elle [ˈɛl.le] | lago [ˈla.ɣ˕u] | /l/ | — |

| M, m | emme [ˈẽ.me] | manno [ˈmɐ̃.nu] | /m/ | — |

| N, n | enne [ˈẽ.ne] | nauþo [ˈnɔ.θu] | /n/ | — |

| O, o | o [ˈɔ] | oþalȯ [oˈθa.lo] | /o/, /u/ or /ɔ/ | ô, ȯ |

| P, p | pi [ˈpi] | paerþa [ˈpɛɾ.t͡θɐ] | /p/ or /f/ | — |

| Q, q | qoppa [ˈkʷɔp.pɐ] | qaerþa [ˈkᶣɛɾ.t͡θɐ] | /kʷ/ | — |

| R, r | erre [ɛˈʀe] | raeda [ˈʁɛ.ð̞ɐ] | /ʀ/, /ʁ/ or /ɾ/ | — |

| S, s | esse [ɛsˈse] | sauila [ˈsɔj.lɐ] | /s/, /t͡s/ or /z/ | — |

| T, t | ti [ˈti] | teivo [ˈti.vu] | /t/ or /θ/ | — |

| Þ, þ | eþþe [ˈɛθ.θe] | þaurno [ˈθɔɾ.nu] | /θ/ or /t͡θ/ | — |

| U, u | u [ˈu] | uro [ˈu.ɾu] | /u/ or /w/ | û, ü |

| V, v | vi [ˈvi] | viġna [ˈviɲ.ɲɐ] | /v/ | — |

| Z, z | zi [ˈt͡si] | zetta [ˈt͡sɛt.tɐ] | /t͡s/ or /d͡z/ | — |

Luthic has geminate, or double, consonants, which are distinguished by length and intensity. Length is distinctive for all consonants except for /d͡z/, /ʎ/, /ɲ/ , which are always geminate when between vowels, and /z/, which is always single. Geminate plosive and affricates are realised as lengthened closures. Geminate fricatives, nasals, and /l/ are realised as lengthened continuants. When triggered by Gorgia Toscana, voiceless fricatives are always constrictive, but voiced fricatives are not very constrictive and often closer to approximants.

Phonology

There is a maximum of 8 oral vowels, 5 nasal vowels, 2 semivowels and 41 consonants; though some varieties of the language have fewer phonemes. Gothic, Frankish, northern Suebi, Langobardic, Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish (Roman Gaul) influences were highly absorbed into the local Vulgar Latin dialect. An early form of Luthic was already spoken in the Ostrogothic Kingdom during Theodoric’s reign and by the year 600 Luthic had already become the vernacular of Ravenna. Luthic developed in the region of the former Ostrogothic capital of Ravenna, from Late Latin dialects and Vulgar Latin. As Theodoric emerged as the new ruler of Italy, he upheld a Roman legal administration and scholarly culture while promoting a major building program across Italy, his cultural and architectural attention to Ravenna led to a most conserved dialect, resulting in modern Luthic.

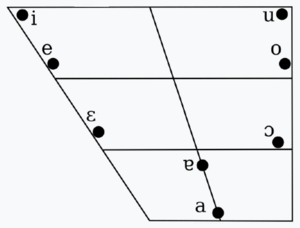

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| Close | i | ĩ | u | ũ | ||

| Close-mid | e | ẽ | o | õ | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɐ | ɐ̃ | ɔ | ||

| Open | a | |||||

Notes

When the mid vowels /ε, ɔ/ precede a nasal, they become close [ẽ] rather than [ε̃] and [õ] rather than [ɔ̃].

- /i/ is close front unrounded [i].

- /u/ is close back rounded [u].

- /e/ is close-mid front unrounded [e].

- /o/ is close-mid back rounded [o].

- /ɛ/ has been variously described as mid front unrounded [ɛ̝] and open-mid front unrounded [ɛ].

- /ɔ/ is somewhat fronted open-mid back rounded [ɔ̟].

- /ɐ/ is near-open central unrounded [ɐ].

- /a/ has been variously described as open front unrounded [a] and open central unrounded [ä].

Diphthongs and triphthongs

| Rising | je | jɛ | jo | jɔ | jɐ | ju |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| we | wɛ | wo | wɔ | wɐ | wi |

| Falling | ej | ɛj | oj | ɔj | ɐj |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ew | ɛw | ow | ɔw | ɐw |

| Rising | jwo |

|---|

| Falling | jɛj | jɔj | jɐj |

|---|---|---|---|

| wɛj | wɔj | wɐj |

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | (ŋʷ) | ||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p, pʰ | t, tʰ | k, kʰ | kʷ | ||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ɡʷ | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s θ | ʃ | ç | (x) | (h) | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʁ | ||||||

| Affricate | voiceless | (p͡f) | t͡s (t͡θ) | t͡ʃ | |||||

| voiceless | d͡z | d͡ʒ | |||||||

| Approximant | semivowel | j | w | ||||||

| lateral | l | ʎ | |||||||

| Gorgia Toscana | (ʋ) | (ð̞) | (ɣ˕) | ||||||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||||

| Trill | ʀ | ||||||||

Notes

- Nasals:

- Plosives:

- /p/, /pʰ/ and /b/ are purely labial.

- /t/, /tʰ/ and /d/ are laminal dentialveolar [t̻, t̻ʰ, d̻].

- /k/ and /ɡ/ are pre-velar [k̟, ɡ̟] before /i, e, ɛ, j/.

- /kʷ/ and /ɡʷ/ are palato-labialised [kᶣ, ɡᶣ] before /i, e, ɛ, j/.

- Affricates:

- /p͡f/ is bilabial–labiodental and is only found as a common allophone.

- /t͡θ/ is dental and is only found as a common allophone.

- /t͡s/ and /d͡z/ are dentalised laminal alveolar [t̻͡s̪, d̻͡z̪].

- /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are strongly labialised palato-alveolar [t͡ʃʷ, d͡ʒʷ].

- Fricatives:

- /f/ and /v/ are labiodental.

- /θ/ is dental.

- /s/ and /z/ are laminal alveolar [s̻, z̻].

- /ʃ/ is strongly labialised palato-alveolar [ʃʷ].

- /x/ is velar, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /ʁ/ is uvular, but in anlaut is in free variation with [h].

- /h/ is glottal, but is in free variation with [x ~ ʁ], /h/ is palatal [ç] nearby /i, e, ɛ, j/. Word initial /h/ is often dropped off.

- Approximants, flap, trill and laterals:

- /ʋ/ is labiodental, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /ð̞/ is dental, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /j/ and /w/ are always geminate when intervocalic.

- /ɾ/ is alveolar [ɾ].

- /ɣ˕/ is velar, and only found when triggered by Gorgia Toscana.

- /ʀ/ is uvular [ʀ], but is in free variation with alveolar [r].

- /l/ is laminal alveolar [l̻].

- /ʎ/ is alveolo-palatal, always geminate when intervocalic.

Historical phonology

The phonological system of the Luthic language underwent many changes during the period of its existence. These included the palatalisation of velar consonants in many positions and subsequent lenitions. A number of phonological processes affected Luthic in the period before the earliest documentation. The processes took place chronologically in roughly the order described below (with uncertainty in ordering as noted).

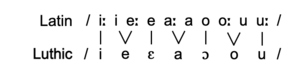

Vowel system

The most sonorous elements of the syllable are vowels, which occupy the nuclear position. They are prototypical mora-bearing elements, with simple vowels monomoraic, and long vowels bimoraic. Latin vowels occurred with one of five qualities and one of two weights, that is short and long /i e a o u/. At first, weight was realised by means of longer or shorter duration, and any articulatory differences were negligible, with the short:long opposition stable. Subtle articulatory differences eventually grow and lead to the abandonment of length, and reanalysis of vocal contrast is shifted solely to quality rather than both quality and quantity; specifically, the manifestation of weight as length came to include differences in tongue height and tenseness, and quite early on, /ī, ū/ began to differ from /ĭ, ŭ/ articulatorily, as did /ē, ō/ from /ĕ, ŏ/. The long vowels were stable, but the short vowels came to be realised lower and laxer, with the result that /ĭ, ŭ/ opened to [ɪ, ʊ], and /ĕ, ŏ/ opened to [ε, ɔ]. The result is the merger of Latin /ĭ, ŭ/ and /ē, ō/, since their contrast is now realised sufficiently be their distinct vowel quality, which would be easier to articulate and perceive than vowel duration.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː ĩː | u uː ũː | |

| Mid | e eː ẽː | o oː õː | |

| Open | ä äː ä̃ː |

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ɪ iː ĩː | ʊ uː ũː | |

| Mid | ε eː ẽː | ɔ oː õː | |

| Open | ä äː ä̃ː |

Unstressed a resulted in a slightly raised a [ɐ]. In hiatus, unstressed front vowels become /j/, while unstressed back vowels become /w/.

In addition to monophthongs, Luthic has diphthongs, which, however, are both phonemically and phonetically simply combinations of the other vowels. None of the diphthongs are, however, considered to have distinct phonemic status since their constituents do not behave differently from how they occur in isolation, unlike the diphthongs in other languages like English and German. Grammatical tradition distinguishes “falling” from “rising” diphthongs, but since rising diphthongs are composed of one semiconsonantal sound [j] or [w] and one vowel sound, they are not actually diphthongs. The practice of referring to them as “diphthongs” has been criticised by phoneticians like Alareico Villavolfo.

Cluster smoothing

Clusters such as -p.t- -k.t- -x.t- are always smoothed to -t.t-.

- Latin aptus [ˈäp.t̪us̠ ~ ˈäp.t̪ʊs̠] > Luthic atto [ˈat.tu]

- Latin āctuālis [äːk.t̪uˈäː.lʲis̠ ~ äːk.t̪uˈäː.lʲɪs̠] > Luthic attuale [ɐtˈtwa.le]

- Gothic ahtau [ˈax.tɔː] > Luthic attau [ˈat.tɔ]

- Gothic nahts [naxts] > Luthic natto [ˈnat.tu]

This is also valid for other CC clusters with similar manner or place.

Absorption of nasals before fricatives

This is the source of such alterations as modern Standard Luthic fimfe [ˈfĩ.(p͡)fe] “five”, monþo [ˈmõ.(t͡)θu] “mouth” versus Gothic 𐍆𐌹𐌼𐍆 [ˈɸimɸ] “id.”, 𐌼𐌿𐌽𐌸𐍃 [ˈmunθs] “id.” and German fünf [fʏnf] “id.”, Mund [mʊnt] “id.”.

Monophthongization

The diphthongs au, ae and oe [au̯, ae̯, oe̯] were monophthongized (smoothed) to [ɔ, ɛ, e] by Gothic influence, as the Germanic diphthongs /ai/ and /au/ appear as digraphs written ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ in Gothic. Researchers have disagreed over whether they were still pronounced as diphthongs /ai̯/ and /au̯/ in Ulfilas' time (4th century) or had become long open-mid vowels: /ɛː/ and /ɔː/: 𐌰𐌹𐌽𐍃 (ains) [ains] / [ɛːns] “one” (German eins, Icelandic einn), 𐌰𐌿𐌲𐍉 (augō) [auɣoː] / [ɔːɣoː] “eye” (German Auge, Icelandic auga). It is most likely that the latter view is correct, as it is indisputable that the digraphs ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ represent the sounds /ɛː/ and /ɔː/ in some circumstances (see below), and ⟨aj⟩ and ⟨aw⟩ were available to unambiguously represent the sounds /ai̯/ and /au̯/. The digraph ⟨aw⟩ is in fact used to represent /au/ in foreign words (such as 𐍀𐌰𐍅𐌻𐌿𐍃 (Pawlus) “Paul”), and alternations between ⟨ai⟩/⟨aj⟩ and ⟨au⟩/⟨aw⟩ are scrupulously maintained in paradigms where both variants occur (e.g. 𐍄𐌰𐌿𐌾𐌰𐌽 (taujan) “to do” vs. past tense 𐍄𐌰𐍅𐌹𐌳𐌰 (tawida) “did”). Evidence from transcriptions of Gothic names into Latin suggests that the sound change had occurred very recently when Gothic spelling was standardised: Gothic names with Germanic au are rendered with au in Latin until the 4th century and o later on (Austrogoti > Ostrogoti).

Palatalisation

Early evidence of palatalized pronunciations of /tj kj/ appears as early as the 2nd–3rd centuries AD in the form of spelling mistakes interchanging ⟨ti⟩ and ⟨ci⟩ before a following vowel, as in ⟨tribunitiae⟩ for tribuniciae. This is assumed to reflect the fronting of Latin /k/ in this environment to [c ~ t͡sʲ]. Palatalisation of the velar consonants /k/ and /ɡ/ occurred in certain environments, mostly involving front vowels; additional palatalisation is also found in dental consonants /t/, /d/, /l/ and /n/, however, these are often not palatalised in word initial environment.

- Latin amīcus [äˈmiː.kus̠ ~ äˈmiː.kʊs̠], amīcī [äˈmiː.kiː] > Luthic amico [ɐˈmi.xu], amici [ɐˈmi.t͡ʃi].

- Gothic giba [ˈɡiβa] > Luthic geva [ˈd͡ʒe.vɐ].

- Latin ratiō [ˈrä.t̪i.oː] > Luthic razione [ʁɐˈd͡zjo.ne]

- Latin fīlius [ˈfiː.li.us̠ ~ ˈfiː.lʲi.ʊs̠] > Luthic fiġlo [ˈfiʎ.ʎu].

- Latin līnea [ˈliː.ne.ä ~ ˈlʲiː.ne.ä] , pugnus [ˈpuŋ.nus̠ ~ ˈpʊŋ.nʊs̠], ācrimōnia [äː.kriˈmoː.ni.ä ~ äː.krɪˈmoː.ni.ä] > Luthic liġna [ˈliɲ.ɲɐ], poġno [ˈpoɲ.ɲu], acremoġna [ɐ.kɾeˈmoɲ.ɲɐ].

Labio-velars remain unpalatalised, except in monosyllabic environment:

- Latin quis [kʷis̠ ~ kʷɪs̠] > Luthic ce [t͡ʃe].

- Gothic qiman [ˈkʷiman] > Luthic qemare [kʷeˈma.ɾe ~ kᶣeˈma.ɾe].

In some cases, palatalisation occurs word initially, mainly if /kn/ is the initial cluster:

- Gothic knōþs [knoːθs] > Luthic ġnode [ˈɲo.ð̞e].

- Gothic kunnan [ˈkunːan], influenced by Latin (co)gnōscere [koŋˈnoːs̠.ke.re ~ kɔŋˈnoːs̠.kɛ.rɛ] and later Langobardic *knājan */ˈknaːjan/ > Luthic ġnoscere [ɲoʃˈʃe.ɾe]

- Langobardic *knohha /ˈknoxːa ~ ˈknɔxːa/ > Luthic ġnocco [ˈɲɔk.ku].

It may not happen if intervocalic:

- Gothic kēlikn [ˈkeːlikn] > Luthic celecna [t͡ʃeˈlek.nɐ].

- Gothic auknan [ˈɔːknan] > Luthic aucnare [ɔkˈna.ɾe].

Lenition

The Gotho-Romance family suffered very few lenitions, but in most cases the stops /p t k/ are lenited to /b d ɡ/ if not in onset position, before or after a sonorant or in intervocalic position as a geminate. A similar process happens with /b/ that is lenited to /v/ in the same conditions. The non-geminate rhotic present in Latin is simplified to /ɾ ʁ/. The unstressed labio-velar /kʷ/ delabialises before hard vowels, as in:

- Gothic ƕan [ʍan] > *[kʷɐn] > Luthic can [kɐn].

- Latin nunquam [ˈnuŋ.kʷä̃ː ~ ˈnʊŋ.kʷä̃ː] > Luthic nogca [ˈnoŋ.kɐ].

Luthic is further affected by the Gorgia Toscana effect, where every plosive is spirantised (or further approximated if voiced). Plosives, however, are not affected if:

- Geminate.

- Labialised.

- Nearby another fricative.

- Nearby a rhotic, a lateral or nasal.

- Stressed and anlaut.

Fortition

In every case, /j/ and /w/ are fortified to /d͡ʒ/ and /v/, except when triggered by hiatus collapse. The Germanic /ð/ and /xʷ ~ hʷ ~ ʍ/ are also fortified to /d/ and /kʷ/ in every position; which can be further lenited to /d͡z/ and /k ~ t͡ʃ/ in the environments given above. The Germanic /h ~ x/ is fortified to /k/ before a rhotic or a lateral, as in:

- Gothic hlaifs [ˈhlɛːɸs] > Luthic claefo [ˈklɛ.fu].

- Gothic hriggs [ˈhriŋɡs ~ ˈhriŋks] > Luthic creggo [ˈkɾeŋ.ɡu].

Coda consonants with similar articulations often sandhi, triggering a kind of syntactic gemination, it also happens with oxytones:

- Ed þû, ce taugis? [e‿θˈθu | t͡ʃe ˈtɔ.d͡ʒis].

- La cittâ stâþ sporca [lɐ t͡ʃitˈta‿sˈsta‿sˈspoɾ.kɐ].

Regarding the absorption of nasals before fricatives, voiceless fricatives are often fortified to affricates after alveolar consonants, such as /n l ɾ/, or general nasals:

- Il monþo [i‿mˈmõ.t͡θu].

- L’inferno [l‿ĩˈp͡fɛɾ.nu].

- La salsa [lɐ ˈsal.t͡sɐ].

- L’arsenale [l‿ɐɾ.t͡seˈna.le].

Deletion

In some rare cases, the consonants are fully deleted (elision), as in the verb havere, akin to Italian avere, which followed a very similar paradigm and evolution:

- 1st person indicative present: Latin habeō, Gothic haba, Luthic hô, Italian ho.

- 2nd person indicative present: Latin habēs, Gothic habais, Luthic hais, Italian hai.

- 3rd person indicative present: Latin habet, Gothic habaiþ, Luthic hâþ, Italian ha.

Vowels other than /a/ are often syncopated in unstressed word-internal syllables, especially when in contact with liquid consonants:

- Latin angulus [ˈäŋ.ɡu.ɫ̪us̠ ~ ˈäŋ.ɡʊ.ɫ̪ʊs̠] > Luthic agglo [ˈaŋ.ɡlu].

- Latin speculum [ˈs̠pɛ.ku.ɫ̪ũː ~ ˈs̠pɛ.kʊ.ɫ̪ũː] ~ Luthic speclȯ [ˈspɛ.klo].

- Latin avunculus [äˈu̯uŋ.ku.ɫ̪us̠ ~ äˈu̯ʊŋ.kʊ.ɫ̪ʊs̠] > Luthic avogclo [ɐˈvoŋ.klu].

Phonotactics

Luthic allows up to three consonants in syllable-initial position, though there are limitations. The syllable structure of Luthic is (C)(C)(C)(G)V(G)(C)(C). As with English, there exist many words that begin with three consonants. Luthic lacks bimoraic (diphthongs and long vowels), as the so-called diphthongs are composed of one semiconsonantal (glide) sound [j] or [w].

| C₁ | C₂ | C₃ |

|---|---|---|

| f v p b t d k ɡ | ɾ | j w |

| s | p k | ɾ l |

| s | f t | ɾ |

| z | b | l |

| z | d ɡ | ɾ |

| z | m n v d͡ʒ ɾ l | — |

| p b f v k ɡ | ɾ l | — |

| ɡ | n l | — |

| pʰ t tʰ kʰ d | ɾ | — |

| θ | v ɾ | — |

| kʷ ɡʷ t͡s t͡ʃ d͡ʒ ʃ h ð ʁ ɲ l ʎ | — | — |

CC

- /s/ + any voiceless stop or /f/;

- /z/ + any voiced stop, /v d͡ʒ m n l ɾ/;

- /f v/, or any stop + /ɾ/;

- /f v/, or any stop except /t d/ + /l/;

- /f v s z/, or any stop or nasal + /j w/;

- In Graeco-Roman words origin which are only partially assimilated, other combinations such as /pn/ (e.g. pneumatico), /mn/ (e.g. mnemonico), /tm/ (e.g. tmesi), and /ps/ (e.g. pseudo-) occur.

As an onset, the cluster /s/ + voiceless consonant is inherently unstable. Phonetically, word-internal s+C normally syllabifies as [s.C]. A competing analysis accepts that while the syllabification /s.C/ is accurate historically, modern retreat of i-prosthesis before word initial /s/+C (e.g. miþ isforza “with effort” has generally given way to miþ sforzȧ) suggests that the structure is now underdetermined, with occurrence of /s.C/ or /.sC/ variable “according to the context and the idiosyncratic behaviour of the speakers.”

CCC

- /s/ + voiceless stop or /f/ + /ɾ/;

- /z/ + voiced stop + /ɾ/;

- /s/ + /p k/ + /l/;

- /z/ + /b/ + /l/;

- /f v/ or any stop + /ɾ/ + /j w/.

| V₁ | V₂ | V₃ |

|---|---|---|

| a ɐ e ɛ | i [j] u [w] | — |

| o ɔ | i [j] | — |

| i [j] | e o | — |

| i [j] | ɐ ɛ ɔ | i [j] |

| i [j] | u [w] | o |

| u [w] | ɐ ɛ ɔ | i [j] |

| u [w] | e o | — |

| u [w] | i | — |

The nucleus is the only mandatory part of a syllable and must be a vowel or a diphthong. In a falling diphthong the most common second elements are /i̯/ or /u̯/. Combinations of /j w/ with vowels are often labelled diphthongs, allowing for combinations of /j w/ with falling diphthongs to be called triphthongs. One view holds that it is more accurate to label /j w/ as consonants and /jV wV/ as consonant-vowel sequences rather than rising diphthongs. In that interpretation, Luthic has only falling diphthongs (phonemically at least, cf. Synaeresis) and no triphthongs.

| C₁ | C₂ |

|---|---|

| m n l ɾ | Cₓ |

| Cₓ | — |

Luthic permits a small number of coda consonants. Outside of loanwords, the permitted consonants are:

- The first element of any geminate.

- A nasal consonant that is either /n/ (word-finally) or one that is homorganic to a following consonant.

- /ɾ/ and /l/.

- /s/ (though not before fricatives).

Prosody

Luthic is quasi-paroxytonic, meaning that most words receive stress on their penultimate (second-to-last) syllable. Monosyllabic words tend to lack stress in their only syllable, unless emphasised or accentuated. Enclitic and other unstressed personal pronouns do not affect stress patterns. Some monosyllabic words may have natural stress (even if not emphasised), but it is weaker than those in polysyllabic words.

- rasda (ʀᴀ-sda ~ ʀᴀs-da) /ˈʁa.zdɐ ~ ˈʁaz.dɐ/;

- Italia (i-ᴛᴀ-lia) /iˈta.ljɐ];

- approssimativamente (ap-pros-si-ma-ti-va-ᴍᴇɴ-te) /ɐp.pɾos.si.mɐ.θi.vɐˈmen.te/.

Compound words have secondary stress on their penultimate syllable. Some suffixes also maintain the suffixed word secondary stress.

- panzar + campo + vaġno > panzarcampovaġno (ᴘᴀɴ-zar-ᴄᴀᴍ-po-ᴠᴀ-ġno) /ˌpan.t͡sɐɾˌkam.poˈvaɲ.ɲu/;

- broþar + -scape > broþarscape (ʙʀᴏ-þar-sᴄᴀ-pe) /ˌbɾo.θɐɾˈska.fe/.

Secondary stress is however often omitted by Italian influence. Tetrasyllabic (and beyond) words may have a very weak secondary stress in the fourth-to-last syllable (i.e. two syllables before the main or primary stress).

Research

Luthic is a well-studied language, and multiple universities in Italy have departments devoted to Luthic or linguistics with active research projects on the language, mainly in Ravenna, such as the Linguistic Circle of Ravenna (Luthic: Creizzo Rasdavitascapetico Ravennai; Italian: Circolo Linguistico di Ravenna) at Ravenna University, and there are many dictionaries and technological resources on the language. The language council Gafaurdo faul·la Rasda Lûthica also publishes research on the language both nationally and internationally. Academic descriptions of the language are published both in Luthic, Italian and English. The most complete grammar is the Grammatica ġli Lûthicae Rasdae (Grammar of the Luthic Language) by Alessandro Fiscar & Luca Vaġnar, and it is written in Luthic and contains over 800 pages. Multiple corpora of Luthic language data are available. The Luthic Online Dictionary project provides a curated corpus of 35,000 words.

History

The Ravenna School of Linguistics evolved around Giovanni Laggobardi and his developing theory of language in linguistic structuralism. Together with Soġnafreþo Rossi he founded the Circle of Linguistics of Ravenna in 1964, a group of linguists based on the model of the Prague Linguistic Circle. From 1970, Ravenna University offered courses in languages and philosophy but the students were unable to finish their studies without going to Accademia della Crusca for their final examinations.

- Ravenna University Circle of Phonological Development (Luthic: Creizzo Sviluppi Phonologici giȧ Accademiȧ Ravennȧ) was developed in 1990, however very little research has been done on the earliest stages of phonological development in Luthic.

- Ravenna University Circle of Theology (Luthic: Creizzo Theologiae giȧ Accademiȧ Ravennȧ) was developed in 2000 in association with the Ravenna Cathedral or Metropolitan Cathedral of the Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ (Luthic: Cathedrale metropolitana deï Osstassi Unsari Siġnori Gesosi Christi; Italian: Cattedrale metropolitana della Risurrezione di Nostro Signore Gesù Cristo; Duomo di Ravenna).

Phonological development

Phonological development refers to how children learn to organize sounds into meaning or language (phonology) during their stages of growth.

Phoneme inventory and phonotactics

Word-final consonants are rarely produced during the early stages of word production. Consonants are usually found in word-initial position, or in intervocalic position. At 6 months, infants are also able to make use of prosodic features of the ambient language to break the speech stream they are exposed to into meaningful units, e.g., they are better able to distinguish sounds that occur in stressed vs. unstressed syllables. This means that at 6 months infants have some knowledge of the stress patterns in the speech they are exposed and they have learned that these patterns are meaningful.

10 months

Most consonants are word-initial only: They are voiced stops /d/, /b/ and the nasal /m/. A presence of voiceless stops is also found as /t/, /p/ and rarely /k/; who can be allphones of each other. A preference for a front place of articulation is present. Clicks are also present, although mostly for imitative suckling sounds.

Babbling becomes distinct from previous, less structured vocal play. Initially, syllable structure is limited to CVCV, called reduplicated babbling. Consonant clusters are still absent. Children’s first ten words appear around month 12, and take CVCV format, such as mama “mother”, papa “father” and dada “give me!”.

21 months

More phones now appear: the nasal /n/, the voiceless fricative /t͡ʃ/, who can be an allphone of /t ~ d/; as voice is still not a distinctive feature, and the liquid /l/. The preference for front articulation is still present, triggering palatalisation.

24 months

Fricatives may appear: /f ~ v/ and /s/ (who can be further palatalised to /ʃ/), primarily at intervocalic position. Voice may become a distinctive feature at this stage. Onomatopoeiae are also produced, such as /aw aw/ for dog’s barking; /ow/, or preferably /aj/ for denoting pain. Production of trisyllabic words begins, such as C₁VC₂VC₃V. Consonant clusters are now present and are often subject to consonant harmony, such as -mb-, -nd- and -dɾ-; however voiced-voiceless clusters are still rare, such as -mp- and -tɾ-.

30 months

Approximately equal numbers of phones are now produced in word-initial and intervocalic position. Additions to the phonetic inventory are the voiced stop /ɡ/ and a few consonant clusters. Co-articulations are perceived, such as labio-velar plosives and the aspirated plosive series. Alveolars and bilabials are the two most common places of articulation. Labiodental and postalveolar production increases throughout development, while velar production decreases. Luthic lenitions also become evident, as more fricatives and approximants are produced. Children develop syllabic segmentation awareness earlier than phonemic segmentation awareness.

Word processes

These phonological processes may happen within a range of 3 to 6 years.

- Nasal assimilation: non-nasal sounds often become nasal sound due to a nasal sound in the word [ˈʁɛn.dɐ] > [ˈnen.nɐ];

- Weak syllable deletion: word-initial and word-terminal unstressed syllables are often omitted [bɐˈna.nɐ] > [ˈna.nɐ];

- Coda deletion: omission of general coda consonant and the final consonant in the word [kɐɾ] > [kɐ], [ˈbɾo.θɐɾ] > [ˈbɾo.θɐ] ([ˈbɾo]);

- Consonant harmony: a target word consonant takes on features of another target word consonant , [kɐn] > [kɐŋ], [ˈstɛk.kɐ] > [ˈstɛt.tɐ] ([ˈstɛt ~ ˈstɛ]);

- Coalescence: adjacent consonants are merged into one with similar features [ˈzbaf.fu] > [ˈvaf.fu];

- Cluster reduction: consonant clusters are often simplifed into a single consonant [oˈʁek.klɐ] > [oˈʁel.lɐ] ([ˈʁel.lɐ]);

- Velar fronting: velar plosives are often replaced by alveolar ones nearby a front vowel [ki] > [ti];

- Stopping or affrication: fricatives are often fortified nearby a front vowel [si] > [ti ~ t͡ʃi];

- Gliding: taps and liquids are replaced by a glide [ˈka.ɾu] > [ˈka.wu], [ˈaʎ.ʎo] > [ˈaj.jo].

6 years

Children produce mostly adult-like segments. Their ability to produce complex sound sequences and multisyllabic words continues to improve throughout middle childhood.

Typology

Luthic has right symmetry, as other VO languages (verb before object) like English.

| Correlation | VO language | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Adposition type | prepositions | of..., than..., on... |

| Order of noun and genitive | noun before genitive | father + of John |

| Order of adjective and standard of comparison | adjective before standard | taller + than Bob |

| Order of verb and adpositional phrase | verb before adpositional phrase | slept + on the floor |

| Order of verb and manner adverb | verb before manner adverb | ran + slowly |

| Order of copula and predicative | copula before predicate | is + a teacher |

| Order of auxiliary verb and content verb | auxiliary before content verb | want + to see Mary |

| Place of adverbial subordinator in clause | clause-initial subordinators | because + Bob has left |

| Order of noun and relative clause | noun before relative clause | movies + that we saw |

WALS

The Atlas of Language Structures (WALS) is a large database of structural (phonological, grammatical, lexical) properties of languages gathered from descriptive materials (such as reference grammars) by a team of 55 authors.

| WALS | Luthic | Italian¹ | Romanian¹ | English | German | Icelandic¹ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headed | Mixed | Mixed | Mixed | Mixed | Mixed | Mixed | |

| Typology | Analytic (partially) | Analytic (partially) | Analytic (partially) | Analytic (partially) | Analytic (partially) | Analytic (partially) | |

| Isochrony | Syllable | Syllable | Stress | Stress | Stress | Syllable | |

| Pro-drop | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Mostly (colloquial) | No | |

| Consonant Inventories | 1A | Large | Average | Average | Average | Average | Average |

| Vowel Quality Inventories | 2A | Large (7-14) | Average (5-6) | Large (7-14) | Large (7-14) | Large (7-14) | Large (7-14) |

| Consonant-Vowel Ratio | 3A | Moderately high | Average | Average | Low | Low | Low |

| Voicing in Plosives and Fricatives | 4A | In both plosives and fricatives | In both plosives and fricatives | In both plosives and fricatives | In both plosives and fricatives | In both plosives and fricatives | In both plosives and fricatives |

| Voicing and Gaps in Plosive Systems | 5A | None missing in /p t k b d g/ | None missing in /p t k b d g/ | None missing in /p t k b d g/ | None missing in /p t k b d g/ | None missing in /p t k b d g/ | None missing in /p t k b d g/ |

| Uvular Consonants | 6A | Uvular continuants only | None | None | None | Uvular continuants only | None |

| Glottalised Consonants | 7A | No glottalised consonants | No glottalised consonants | No glottalised consonants | No glottalised consonants | No glottalised consonants | No glottalised consonants |

| Lateral Consonants | 8A | /l/, no obstruent laterals | /l/, no obstruent laterals | /l/, no obstruent laterals | /l/, no obstruent laterals | /l/, no obstruent laterals | /l/, no obstruent laterals |

| The Velar Nasal | 9A | No initial velar nasal | No velar nasal | No velar nasal | No initial velar nasal | No initial velar nasal | No initial velar nasal |

| Vowel Nasalisation | 10A | Contrast present | Contrast absent | Contrast absent | Contrast absent | Contrast absent | Contrast absent |

| Front Rounded Vowels | 11A | None | None | None | None | High and mid | High and mid |

| Syllable Structure | 12A | Complex | Moderately complex | Moderately complex | Complex | Complex | Complex |

| Fixed Stress Locations | 14A | No fixed stress | No fixed stress | No fixed stress | No fixed stress | No fixed stress | Initial |

| Weight-Sensitive Stress | 15A | Right-oriented: One of the last three | Right-edge: Ultimate or penultimate | Right-edge: Ultimate or penultimate | Right-oriented: One of the last three | Right-oriented: One of the last three | Fixed stress (no weight-sensitivity) |

| Weight Factors in Weight-Sensitive Stress Systems | 16A | Lexical stress | Lexical stress | Lexical stress | Long vowel or coda consonant | Coda consonant | No weight |

| Rhythm Types | 17A | Undetermined | Undetermined | Undetermined | Trochaic | Trochaic | Trochaic |

| Absence of Common Consonants | 18A | All present | All present | All present | All present | All present | All present |

| Presence of Uncommon Consonants | 19A | ‘Th’ sounds | None | None | ‘Th’ sounds | None | ‘Th’ sounds |

| Fusion of Selected Inflectional Formatives | 20A | Exclusively concatenative | Exclusively concatenative | Exclusively concatenative | Exclusively concatenative | Exclusively concatenative | Exclusively concatenative |

| Exponence of Tense-Aspect-Mood Inflection | 21B | TAM+agreement | TAM+agreement | TAM+agreement | Monoexponential TAM | Monoexponential TAM | Monoexponential TAM |

| Inflectional Synthesis of the Verb | 22A | 4-5 categories per word | 4-5 categories per word | 4-5 categories per word | 2-3 categories per word | 2-3 categories per word | 2-3 categories per word |

| Locus of Marking in the Clause | 23A | Double marking | Double marking | Double marking | Dependent marking | Dependent marking | Dependent marking |

| Locus of Marking in Possessive Noun Phrases | 24A | Dependent marking | Dependent marking | Dependent marking | Dependent marking | Dependent marking | Dependent marking |

| Locus of Marking: Whole-language Typology | 25A | Inconsistent or other | Inconsistent or other | Inconsistent or other | Dependent-marking | Dependent-marking | Dependent-marking |

| Zero Marking of A and P Arguments | 25B | Non-zero marking | Non-zero marking | Non-zero marking | Non-zero marking | Non-zero marking | Non-zero marking |

| Prefixing vs. Suffixing in Inflectional Morphology | 26A | Strongly suffixing | Strongly suffixing | Strongly suffixing | Strongly suffixing | Strongly suffixing | Strongly suffixing |

| Reduplication | 27A | No productive reduplication | No productive reduplication | No productive reduplication | No productive reduplication | No productive reduplication | No productive reduplication |

| Case Syncretism | 28A | Core and non-core | Core and non-core | Core and non-core | Core cases only | Core and non-core | Core and non-core |

| Syncretism in Verbal Person/Number Marking | 29A | Syncretic | Syncretic | Syncretic | Syncretic | Syncretic | Syncretic |

- ¹ Some features and values are stipulated due to lack of resources.

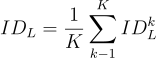

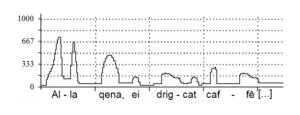

Information rate

The concept of “information density” relates to how languages convey semantic information within the speech signal. Essentially, a language is considered dense if it uses fewer speech elements to convey a given amount of semantic meaning compared to a sparser language. Units such as features or articulatory gestures involve complex multidimensional patterns (such as gestural scores or feature matrices) that are unsuitable for computing average information density during speech communication. In contrast, each speech sample can be described in terms of discrete sequences of segments or syllables, which are potential candidates, although their exact significance and role in communication remain uncertain. Therefore, this study opts to utilise syllables for both methodological and theoretical reasons.

Assuming that for each text Tk, composed of σk(L) syllables in language L, the over-all semantic content Sk is equivalent from one language to another, the average quantity of information per syllable for Tk and for language L is calculated as in 1.

Since Sk is language-independent, it was eliminated by computing a normalised information density (ID) using Vietnamese (VI) as the benchmark. For each text Tk and language L, IDkL resulted from a pairwise comparison of the text lengths (in terms of syllables) in L and VI respectively.

Next, the average information density IDL (in terms of linguistic information per syllable) with reference to VI is defined as the mean of IDkL evaluated for the K texts.

| Language | IDL | Syllabic rate | Information rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | 0.91 | 6.19 | 1.08 |

| French | 0.74 | 7.18 | 0.99 |

| Italian | 0.72 | 6.99 | 0.96 |

| Spanish | 0.63 | 7.82 | 0.98 |

| German | 0.79 | 5.67 | 0.90 |

| Luthic | 0.81 | 6.45 | 0.97 |

| Vietnamese | 1 (reference) | 5.22 | 1 (reference) |

Another factor is the syllabic complexity index, being measured in two ways: type and token.

- Type complexity: considers each unique syllable only once when calculating the average complexity.

- Token complexity: takes into account the frequency of occurrence of each unique syllable in the corpus by weighting the complexity accordingly.

| Language | Syllable inventory size | Type complexity | Token complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | 7,931 | 3.70 | 2.48 |

| French | 5,646 | 3.50 | 2.21 |

| Italian | 2,719 | 3.50 | 2.30 |

| Spanish | 1,593 | 3.30 | 2.40 |

| German | 4,207 | 3.70 | 2.68 |

| Luthic | 4,129 | 3.60 | 2.40 |

The Handbook of Luthic Linguistics, Culture and Religion

Aena lettura essenziale summȧ importanzȧ, inu andarogiugga.

“An essential lecture, of the highest importance, without equivalents.”

In 2012, a collaboration of the Circle of Linguistics, the Circle of Phonological Development and the Circle of Theology resulted in The Handbook of Luthic Linguistics, Culture and Religion (Luthic: Il Handobuoco Rasdavitascapeticae, Colturae e Religioni Lûthicae) initiated in 2005 by Lucia Giamane, designed to illuminate an area of knowledge that encompasses both general linguistics and specialised, philologically oriented linguistics as well as those fields of science that have developed in recent decades from the increasingly extensive research into the diverse phenomena of communicative action.

Mnemonics

A mnemonic device (/nɪˈmɒnɪk/ nih-MON-ik) or memory device is any learning technique that aids information retention or retrieval in the human memory, often by associating the information with something that is easier to remember.

A Luthic mnemonic verse or mnemonic rhyme is a mnemonic device for teaching and remembering Luthic grammar. Such mnemonics have been considered by teachers to be an effective technique for schoolchildren to learn the complex rules of Luthic accidence and syntax. Mnemonics may be helpful in learning foreign languages, for example by transposing difficult foreign words with words in a language the learner knows already, also called “cognates” which are very common in Romance languages and other Germanic languages. A useful such technique is to find linkwords, words that have the same pronunciation in a known language as the target word, and associate them visually or auditorially with the target word; such tecniques have been applied into Luthic learning for children, Italian and other dialleti speakers.

A Luthic rhyme for remembering the masculine nominative singular, masculine accusative singular and neuter nominato-accusative singular is given by many teachers during school first years:

buono: veġlȯ vessare

buonȯ: veġlȯ stare

ac e buonȯ? veġlȯ mangiare!

Translated it into English as follows:

good: I want to be

in a good place: I want to be in

but what about a good food? I want to eat!

The Ravenna University Circle of Phonological Development also found out that mnemonics can be used in aiding children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other neurodevelopmental disorders, patients with memory deficits that could be caused by head injuries, strokes, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis and other neurological conditions, however, in the case of stroke patients, the results did not reach statistical significance.

Grammar

Luthic Grammar is the body of rules describing the properties of the Luthic language. Luthic words can be divided into the following lexical categories: articles, nouns, adjectives, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, and interjections.

Nouns

Luthic grammar is almost typical of the grammar of Romance languages in general. Cases exist for personal pronouns (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), and unlike other Romance languages (except Romanian), they also exist for nouns, but are often ignored in common speech, mainly because of the Italian influence, a language who lacks noun cases. There are three basic classes of nouns in Luthic, referred to as genders, masculine, feminine and neuter. Masculine nouns typically end in -o, with plural marked by -i, feminine nouns typically end in -a, with plural marked by -ae, and neuter nouns typically end in -ȯ, with plural marked by -a. A fourth category of nouns is unmarked for gender, ending in -e in the singular and -i in the plural; a variant of the unmarked declension is found ending in -r in the singular and -i in the plural, it lacks neuter nouns:

Examples:

| Definition | Gender | Singular nominative | Plural nominative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Son | Masculine | Fiġlo | Fiġli |

| Flower | Feminine | Bloma | Blomae |

| Fruit | Neuter | Acranȯ | Acrana |

| Love | Masculine | Amore | Amori |

| Art | Feminine | Crafte | Crafti |

| Water | Neuter | Vadne | Vadni |

| King | Masculine | Regġe | Regġi |

| Heart | Neuter | Haertene | Haerteni |

| Father | Masculine | Fadar | Fadari |

| Mother | Feminine | Modar | Modari |

Declension paradigm in formal Standard Luthic:

| Number | Case | o-stem m | a-stem f | o-stem n | i-stem unm | r-stem unm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | nom. | dago | geva | hauviþȯ | crafte | broþar |

| acc. | dagȯ | geva | hauviþȯ | crafte | broþare | |

| dat. | dagȧ | gevȧ | hauviþȧ | crafti | broþari | |

| gen. | dagi | gevae | hauviþi | crafti | broþari | |

| Plural | nom. | dagi | gevae | hauviþa | crafti | broþari |

| acc. | dagos | gevas | hauviþa | craftes | broþares | |

| dat. | dagom | gevam | hauviþom | craftivo | broþarivo | |

| gen. | dagoro | gevaro | hauviþoro | craftem | broþarem |

A small class of quasi-irregular nouns is found, itself being a variant of the unmarked class. The nominative forms always are oxytones and hide their consonant stem -d-. These are often called d-stem:

| Number | Case | d-stem unm | d-stem unm | d-stem unm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | nom. | piê | fê | -tâ |

| acc. | piede | fede | -tade | |

| dat. | piedi | fedi | -tadi | |

| gen. | piedi | fedi | -tadi | |

| Plural | nom. | piedi | fedi | -tadi |

| acc. | piedes | fedes | -tades | |

| dat. | piedivo | fedivo | -tadivo | |

| gen. | piedem | fedem | -tadem |

Pronouns

Luthic, like Latin and Gothic, inherited the full set of Indo-European pronouns: personal pronouns (including reflexive pronouns for each of the three grammatical persons), possessive pronouns, both simple and compound demonstratives, relative pronouns, interrogatives and indefinite pronouns. Each follows a particular pattern of inflection (partially mirroring the noun declension), much like other Indo-European languages. Although Luthic inherited a paradigm extremely close to Gothic (and Common Germanic), the Italic influence is visible in the genitive and plural formations.

| PIE | Latin | Gothic | German | Luthic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *u̯ei̯ nom, *n̥s acc | nōs nom/acc | 𐍅𐌴𐌹𐍃 nom, 𐌿𐌽𐍃 acc | wir nom, uns acc | vi nom, unse acc |

| Number | Case | 1st person | 2st person | 3rd person | reflexive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | |||||

| Singular | nom. | ic | þû | is | ia | ata | — |

| acc. | mic | þuc | inȯ | ina | ata | sic | |

| dat. | mis | þus | iȧ | iȧ | iȧ | sis | |

| dat. | meina | þeina | eis | isae | eis | seina | |

| Singular | nom. | vi | gi | eis | isae | ia | — |

| acc. | unse | isve | eis | isas | ia | sic | |

| dat. | unsis | isvis | eis | eis | eis | sis | |

| gen. | unsara | isvara | eisôro | eisâro | eisôro | seina | |

Pronouns often a clitic with imperative or after non-finite forms of verbs, being applied as enclitics.

| Number | Case | 1st person | 2st person | 3rd person | reflexive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | |||||

| Singular | acc. | mi | þi ti¹ di² |

lȯ | la | lȯ | si |

| dat. | mi | þi ti¹ di² |

ġli | ġle | ġli | si | |

| gen. | — | — | ne | ne | ne | ne | |

| Plural | acc. | ci | vi | los | las | la | si |

| dat. | ci | vi | li | li | li | si | |

| gen. | — | — | ne | ne | ne | ne | |

- ¹ before voiceless fricatives or sonorants

- ² before voiced fricatives or sonorants

- These forms are often ignored or regarded as hypercorrection, commoner in Italian influenced sociolects.

| Number | Case | 1st person | 2st person | 3rd person | reflexive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | |||||

| Singular | nom. | io | þû | is | ia | ata | — |

| acc. | me | þe | inȯ | ina | ata | sic | |

| dat. | mi | þi | iȧ | iȧ | iȧ | sis | |

| dat. | meina | þeina | eis | isae | eis | seina | |

| Singular | nom. | nôi | vôi | eis | isae | ia | — |

| acc. | nôi | vôi | eis | isas | ia | sic | |

| dat. | ci | vi | eis | eis | eis | sis | |

| gen. | nosâra | vosâra | eisôro | eisâro | eisôro | seina | |

- These forms are also common in everday speech due to Italian influence. Nevertheless, both declension paradigmata are considered to be correct. Main differences are emphasised.

| Number | Case | 1st person singular | 2st person singular | 3rd person singular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | meino | meina | meinȯ | þeino | þeina | þeinȯ | seino | seina | seinȯ |

| acc. | meinȯ | meina | meinȯ | þeinȯ | þeina | þeinȯ | seinȯ | seina | seinȯ | |

| dat. | meinȧ | meinȧ | meinȧ | þeinȧ | þeinȧ | þeinȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | |

| gen. | meini | meinae | meini | þeini | þeinae | þeini | seini | seinae | seini | |

| Plural | nom. | meini | meinae | meina | þeini | þeinae | þeina | seini | seinae | seina |

| acc. | meinos | meinas | meina | þeinos | þeinas | þeina | seinos | seinas | seina | |

| dat. | meinom | meinam | meinom | þeinom | þeinam | þeinom | seinom | seinam | seinom | |

| gen. | meinoro | meinaro | meinoro | þeinoro | þeinaro | þeinoro | seinoro | seinaro | seinoro | |

| Number | Case | 1st person singular | 2st person singular | 3rd person singular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | unsar | unsara | unsarȯ | isvar | isvara | isvarȯ | seino | seina | seinȯ |

| acc. | unsare | unsara | unsarȯ | isvare | isvara | isvarȯ | seinȯ | seina | seinȯ | |

| dat. | unsari | unsarȧ | unsarȧ | isvari | isvarȧ | isvarȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | seinȧ | |

| gen. | unsari | unsarae | unsari | isvari | isvarae | isvari | seini | seinae | seini | |

| Plural | nom. | unsari | unsarae | unsara | isvari | isvarae | isvara | seini | seinae | seina |

| acc. | unsares | unsaras | unsara | isvares | isvaras | isvara | seinos | seinas | seina | |

| dat. | unsarivo | unsaram | unsarom | isvarivo | isvaram | isvarom | seinom | seinam | seinom | |

| gen. | unsarem | unsararo | unsaroro | isvarem | isvararo | isvaroro | seinoro | seinaro | seinoro | |

The pronouns unsar, isvar have an irregular declension, being declined like an unmarked adjective in the masculine gender and marked in the other genders. Every possessive pronoun is declined like an o-stem adjective for masculine and neuter gender, while its feminine counterpart is declined as an a-stem adjective

Interrogative and indefinite pronouns are indeclinable by case and number:

| Interrogative pronouns | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|---|

| What | ce | ce | ce |

| Who | qo | qa | qȯ |

| Whom | ci | ci | ci |

| Which | carge | carge | carge |

| Whose | cogio | cogia | cogiȯ |

| Indefinite pronouns | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Each | caso | casa | casȯ |

| Every | cargiso | cargisa | cargisȯ |

| Whoever/Whatever | þecargiso | þecargisa | þecargisȯ |

The relative pronoun ei is fully indeclinable, it is sometimes called “common relative particle”.

Luthic has a Proximal-Medial-Distal demonstrative system:

| Number | Case | Proximal | Medial | Distal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | so | sa | þata | este | esta | estȯ | giaeno | giaena | giaenȯ |

| acc. | þȯ | þa | þata | este | esta | estȯ | giaenȯ | giaena | giaenȯ | |

| dat. | þammo | þisae | þammo | esti | estȧ | estȧ | giaenȧ | giaenȧ | giaenȧ | |

| gen. | þis | þisae | þis | estis | estae | esti | giaeni | giaenae | giaeni | |

| Plural | nom. | þi | þae | þa | esti | estae | esta | giaeni | giaenae | giaena |

| acc. | þos | þas | þa | estes | estas | esta | giaenos | giaenas | giaena | |

| dat. | þom | þam | þom | estivo | estam | estom | giaenom | giaenam | giaenom | |

| gen. | þisaro | þisara | þisaro | estem | estaro | estoro | giaenoro | giaenaro | giaenoro | |

Articles

Luthic articles are used similarly to the English articles, a and the. However, they are declined differently according to the number, gender and case of their nouns.

| Number | Case | Indefinite | Definite | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Singular | nom. | aeno | aena | aenȯ | il | la | lata, ata |

| acc. | aenȯ | aena | aenȯ | lȯ | la | lata, ata | |

| dat. | aenȧ | aenȧ | aenȧ | lȧ | lȧ | lȧ | |

| gen. | aeni | aenae | aeni | ġli, i | ġli, i | ġli, i | |

| Plural | nom. | aeni | aenae | aena | ġli, i | lae | la |

| acc. | aenos | aenas | aena | los | las | la | |

| dat. | aenom | aenam | aenom | lom | lam | lom | |

| gen. | aenoro | aenaro | aenoro | loro | loro | loro | |

Adjectives