Chlouvānem: Difference between revisions

| Line 1,108: | Line 1,108: | ||

[[Category:A priori]] | [[Category:A priori]] | ||

[[Category:Artlangs]] | [[Category:Artlangs]] | ||

[[Category:Calémere]] | |||

[[Category:Lahob languages]] | [[Category:Lahob languages]] | ||

[[Category:Fusional languages]] | [[Category:Fusional languages]] | ||

Revision as of 22:05, 25 August 2017

| Chlouvānem | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [[Help:IPA|[[c͡ɕʰɴ̆ɔʊ̯ˈʋaːnumʲi dɛɴ̆ˈdaː], also [c͡ɕʰɴ̆oː-]]]] |

| Created by | Lili21 |

| Date | Dec 2016 |

| Setting | Calémere |

| Ethnicity | Chlouvānem |

| Native speakers | 1,450,000,000 (4E Ɛ1) |

Lahob

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | lands of the Inquisition, Brono, Fathan, Ikalurilut, Gorjan (regional) |

| Regulated by | Inquisitorial Office of the Language (dældi flušamila) |

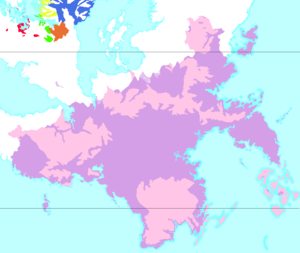

Chlouvānem, natively chlouvānumi dældā ("language of the Chlouvānem people"), is the most spoken language on the planet of Calémere (Chl.: Liloejāṃrya). It is the official language of the Inquisition (murkadhāna) and its country, the Chlouvānem lands (chlouvānumi bhælā[1]), and a lingua franca in many areas of the eastern part of the continent of Evandor. Despite the fact that local vernaculars in most of the Inquisition are in fact daughter languages of Chlouvānem or creoles based on it, the chlouvānumi dældā is a fully living language as every Chlouvānem person is bilingual in it and in the local vernacular, and in fact in the last half century the Chlouvānem language itself has been replacing some vernaculars as internal migrations have become more and more common. About 1,4 billion people on the planet define themselves as native Chlouvānem speakers, more than for any other Calémerian language.

→ See Chlouvānem lexicon for a list of common words.

External History

Chlouvānem is the ninth radically restructured version of Laceyiam; I started creating it in late November 2016 as I found some parts of my conworld which were too unrealistic to work - and as such by changing the whole conworld I had to change the language. I took that opportunity to change some things in the grammar that, while I liked them and they worked well, I wanted to do in some different way — mainly this arises from my love of more complex inflection patterns. As such, compared to Laceyiam, Chlouvānem has much more influences from Sanskrit and Lithuanian (which always were my main influences anyway); other natlangs that influenced me a lot are Russian, Adyghe, Latvian, Old Norse (and to a lesser extent also Danish and Icelandic), Proto-Indo-European, (Biblical) Hebrew, Latin, and Japanese, while its actual in-world use is inspired by Arabic. Still it is an a priori language and, despite having much in common with all of these (particularly with the IE ones), is also strikingly different (the Austronesian morphosyntactic alignment, morphological expression of evidentiality and more broadly the particular emphasis on moods probably being the most noticeable things). Moreover, I tried to create a language very different from my native language (Italian) while keeping many - not so apparent - similarities.

The morphology of Chlouvānem is very different from Laceyiam, though many words are still the same (like smrāṇa (spring), junai (foot), jāyim (girl), saṃhāram (boy)).

As I mentioned before, Chlouvānem is the latest version of the conlang for my main conculture. I started sketching conlangs back when I was 9 or 10 but only started interesting myself into linguistics seven years later - in 2014 - and since then I started doing more "serious" conlangs (the earlier ones were little more than relexified Italian). Ideally, Chlouvānem is the refined version of all of these languages, but except for a few recurring words (like maila (water) or hulin (woman)) it is only comparable to those languages I have been creating since July 2015.

Chlouvānem is mainly thought for my conworld, but more than any other conlang of mine it is quite on the border between an art- and a heartlang.

Variants

Chlouvānem as spoken today is the standardized version of the literary language of the early-mid Second Era Lāmiejāya plain, the one in which most sacred texts of the Yunyalīlta are written. Since then, the language has been kept alive for more than 1500 years and counting in a diglossic state with many descendant and creole languages developing in the areas that gradually came under Chlouvānem control, and Classical Chlouvānem is in fact a major defining factor of Chlouvānem ethnicity, enabling the existence of a single cultural area spread across half a continent despite the individual areas each having their own vernaculars.

Pronunciations

It’s not easy to define “dialects” for Chlouvānem, due to this history: all true dialects of Chlouvānem eventually developed into distinct vernaculars, and today’s regional variations are as such defined as “pronunciations” of Chlouvānem, in some cases moderately divergent from the standard one. Chlouvānem sources refer to them as bhælāyāṃsai “land-sounds”, but they do not only vary in pronunciation. Each major geographic area of the Inquisition has its own pronunciation; present-day standard Chlouvānem is based on the pronunciation in the city of Līlasuṃghāṇa around 4E 60, but the local pronunciation has somewhat diverged, so that the city where the traditional pronunciation is closest to the standard is Galiākina, some 300 km further west. Local pronunciations are typically divided in six major groups by geographic areas:

- Jade Coast, Rainforest, and Eastern Plain (lūṇḍhyalėnei nanayi no naleidhoyi no), including pronunciations of the eastern part of the Lāmiejāya plain, the Jade Coast, and its interior (the main Chlouvānem heartlands and the northern parts of the rainforest). Standard Chlouvānem is one of these.

- Western Plain and Sand Coast (samvāldhoyi chleblėnei no), including the whole western part of the Lāmiejāya plain and the Sand Coast in the central-western Inquisition.

- Far Eastern (lallanaleiyutei), including the Far Eastern part of the Inquisition (both mainland and insular); the dioceses of the so-called Near East are frequently considered a transitional zone between this and the Eastern Plain pronunciation group.

- Eastern (naleiyutei), in the Chlouvānem East (the former Kans-Tsan area).

- Northeastern (kehamnaleiyutei), in the Northeast of the Inquisition; note that the most remote areas (the far northern taiga and the insular part), due to continuous and relatively recent immigration, have a pronunciation still closer to Standard Chlouvānem.

- Western (samvālyutei), in the Western dioceses and in the coasts of the desert. As these were formerly Dabuke areas, they use distinctly more Dabuke terms than all other speakers.

Areas that do not fit in any of these groupings are often recent colonizations (or “Chlouvānemizations”), like e.g. the northern coast on the Skyrdegan Inner Sea, that do not have a truly distinct pronunciation, being a mix of speakers from different areas and tending to be very close to Standard Chlouvānem.

Vernaculars

Local vernaculars of the Inquisition (bhælāmaivai, sg. bhælāmaiva, literally “land word(s)”) are, linguistically, the daughter languages of Classical Chlouvānem. They are the result of normal language evolution with, in most areas, enormous influences by substrata.

Actually, only a bit more than half of the Inquisition has a vernacular that is a true daughter language - most areas conquered in the last 600 years, thus since the sixth or seventh century of the Third Era, speak a creole language, where lexicon is almost completely Chlouvānem but grammar still shows huge semplifications and analytic constructions and some traits odd for Chlouvānem and those languages that developed in the heartlands. Most of the Eastern languages, however, are thought to have origined as creoles.

The main division for local vernaculars - or Chlouvānem languages - is the one in groups, as few of them are standardized and large areas are dialect continua where it is extremely difficult to determine which dialects belong to a particular language and which ones do not. Furthermore, most people speak of their vernacular as “the word of [village name]”, and always refer to them as local variants of the same Chlouvānem language, without major distinctions from the national language which is always Classical Chlouvānem. Individual “languages” are thus simply defined starting from the diocese they’re spoken in, so for example the Nanašīrami language includes all dialects spoken in the diocese of Nanašīrama, despite those spoken in the eastern parts of the diocese being closer to those spoken in Takaiyanta than to the Nanašīrami dialect of Līlasuṃghāṇa.

Note that the word maiva, in Chlouvānem, only identifies a language spoken in a certain area which is typically considered to belong to a wider language community, independent of its origin. It does not have any pejorative meaning, unlike examples like e.g. lingua vs. dialetto in Italian.

The main divisions are:

- Eastern Plain/Jade Coast (naleidhoyi lūṇḍhyalėnei no maivai) — spoken in most of the Lāmiejāya Plain, in the Jade Coast and its interior, and the northern part of the southern rainforest;

- Western Plain (samvāldhoyi maivai) — spoken in the westermost parts of the Lāmiejāya Plain;

- Jungle Language (nanaimaiva) — spoken throughout the southern rainforest;

- Northern Plain (kehaṃdhoyi maivai) — spoken in the northern part of the Lāmiejāya Plain (the upper basin of the Lāmberah river);

- Near Eastern (mūtiānaleiyutei maivai) — spoken in the Near East, or the parts of the Central East west of the Kārmādhona mountains;

- Far Eastern (lallanaleiyutei maivai) — spoken in the Far East (east of the Kārmādhona mountains) and in the eastern islands;

- Kaṃsatsāni (kaṃsatsāni maivai) — spoken in the historic region of Kaṃsatsāna (the Eastern Tribunal);

- Sand Coast (chleblėnei maivai) — spoken on the Sand Coast (west of the Lāmiejāya plain) and by communities in the southern Salt Desert;

- Ajāṣṭri-Mbusakitvi (ajāṣṭri-mbusakitvi maivai) — spoken in the dioceses of Ajāṣṭra and Mbusakitva, west of the Salt Desert. They are often grouped (especially in common speech) with the other Western languages, but those have a clear creole origin not recognizable in Ajāṣṭri and Mbusakitvi.

The other languages were all born as creoles:

- Northeastern (kehamnaleyutei maivai) — various creoles spoken in the Near Northeast;

- Western (samvālyutei maivai) — creoles spoken in the West, with extensive Dabuke influence;

- Najlājātei (najlājātei maiva) — creole spoken in the diocese of Najlājātia, an endorheic basin nestled between the mountains and the desert in the northwestern Inquisition;

- Kāyīchi (kāyīchi maiva) — creole spoken in the insular diocese of Kāyīchah, off the coasts of Védren. It is the least Chlouvānemized creole, as it has substantial influences both from indigenous Vedrenic languages and Cerian, due to the history of these islands, settled in part by Chlouvānem people (by the then-independent Lūlunimarti Republic) and in part by Cerians with Vedrenic slaves, and long fought between the two countries due to their strategic importance.

Many other areas, most notably the North and the far Northeast, do not have a local vernacular, due to Chlouvānem presence there being recent and those areas being either previously almost uninhabited (the far Northeast) or with lots of different ethnicities (the North). The main vernaculars that are actually languages that do not have Chlouvānem origin (and are commonly referred to as dældā instead of maiva) are:

- Basaumi (Bazá), the most spoken, in the ethnic diocese of Tūnambasā, the westernmost on the mainland, where it is the native language of 78% of all inhabitants;

- Hūnakañumi (Huwən-aganь-sisaat), in the mountainous areas of Hūnakañjātia ethnic diocese in the Near East (note that most of the diocese, including the city of Līlekhaitė, 10th largest in the Inquisition, mostly speaks the local Near Eastern language, derived from Chlouvānem)

- Tumidumi (sokaw y ee-tumið), in the ethnic diocese of Tumidajātia in the Near East - mostly spoken in the hills and mountains;

- Kotayumi (kotaii šɔt), in a few mountain villages in Kotaijātia ethnic diocese, Near East;

- Tendukumi (tənduk sisod) in Tendukijātia ethnic diocese, Near East — by percentage of people in its native area, it is the second most spoken, being the native language of 29% of people there, though it is the least populated diocese in that area.

- Tanomali (nzɛk pɔb) on Tanomaliė island, the southernmost of the Eastern Islands.

Historical dialects

Phonology - Yāṃstarlā

Consonants - Hīmbeyāṃsai

Chlouvānem has a large consonant inventory, with 47 different consonants, divided into seven categories: labials, dentals, palatalized dentals, retroflexes, palatals, velars, and laryngeals. The Chlouvānem term for "consonant" is hīmbeyāṃsa, a compound of hīmba (colour) and yāṃsa (sound).

| → PoA ↓ Manner |

Labials hærṣokæh |

Dentals aṣṭrūkæh |

Retroflexes āḍhyāsūkæh |

Palatals dehāṃlūdvyūkæh |

Velars bhyodilūdvyūkæh |

Laryngeals diṇḍhūkæh | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain pūdræh |

Palatalized pindehāṃlūdvyūkæh | |||||||

| Nasals | m mʲ | n | nʲ | ɳ | ɲ | ɴ | ||

| Stops | Unvoiced | p pʰ | t̪ t̪ʰ | tʲ tʲʰ | ʈ ʈʰ | k kʰ | ʔ | |

| Voiced | b bʱ | d̪ d̪ʱ | dʲ dʲʱ | ɖ ɖʱ | g gʱ | |||

| Affricates | Unvoiced | c͡ɕ c͡ɕʰ | ||||||

| Voiced | ɟ͡ʑ ɟ͡ʑʱ | |||||||

| Fricatives | f | s | sʲ | ʂ | ɕ | ɦ | ||

| Approximants | ʋ | j | ʀ ʀʲ ɴ̆ ɴ̆ʲ | |||||

There are only a few instances of consonant allophony, mostly due to the large number of phonemic consonants. The following ones apply to standard Chlouvānem:

- All dentals are allophonically palatalized before /i iː i̤/, thus the palatalized/plain contrast is neutralized there.

- Coda /ʀ/ is diphthongized to [ɐ̯].

- /ɴ/ has two different realizations depending on context: [ɴ] before other laryngeals, and nasalization of the preceding vowel anywhere else.

- Word-final /n/ is realized as [ŋ] after high vowels, and as vowel nasalization after the other ones.

- Nasals, except /ɴ/ before non-laryngeals, assimilate to the PoA of the following consonant, except for /j/ (note that /ɴj/ does not exist).

Not proper of standard Chlouvānem but so widespread it is now by far the most common pronunciation is also the fall of /j/ and /ʋ/ before /i iː i̤/ or /u uː ṳ/ respectively, e.g. in yinām /jinaːm/ [iˈnaːm] (protection, refuge) or vurāṇa /ʋuʀaːɳa/ [uˈʀaːɳa] (a kind of small-sized reptile)[2]. This also leads to phonetic hiatuses, like in Kāyīchah /kaːjiːc͡ɕʰaɦ/ [kaːˈiːc͡ɕʰaɦ] (an insular diocese between Mārṣūtram and Vedren) or the common given name Martayinām /maʀtajinaːm/ [maɐ̯ta.iˈnaːm].

A similarly widespread but not standard allophony is the use of either [ɻ] or [ɽ] for /ʀ/ before /ɖ ɖʱ/, as in larḍhīka (girl, maid) /ɴ̆aʀɖʱiːka/ [ɴ̆aɻˈɖʱiːka].

Pronouncing /ʀʲ/ as [ʐ] or [ʑ] is also a fairly common thing across the East and Northeast; it is nearly universal among young people and in certain areas (most notably the area of the Padeikoli Gulf, including most of the diocese of Padeikola, coastal areas of Lågnemba, and the northern third of Hachitama) it is the norm, with [ʀʲ] being found only as a gerontolectal feature. The palatalized stops are also often pronounced with a noticeable sibilant release, especially in the eastern part of the Jade Coast among younger speakers.

There are also lots of regional variations for /ɦ/ at the end of a word, with a particularly common realization being [χ] (as in e.g. Līlasuṃghāṇa and Galiākina), like lilah /ɴ̆ʲiɴ̆aɦ/ [ˈɴ̆ʲiɴ̆aχ] (I/(s)he/it/they live(s)).

Vowels - Camiyāṃsai

The vowel inventory of Chlouvānem is fairly large too, consisting of 25 phonemes: 14 monophthongs, 9 diphthongs, and 2 syllabic consonants.

Phonetically, there are also nasal vowels, but they are phonemically /Vɴ/ or (word-finally) /Vn/ sequences. On the contrary, breathy-voiced vowels may phonetically surface as [Vh] or [Vχ] in some contexts (most notably before stops) in some pronunciations — e.g. tąkis /tɑ̤kis/ (a kind of herb) pronounced in Cami as [ˈtaxkʲis].

The term for vowel is camiyāṃsa, from cami (great, large, important) and yāṃsa (sound), as these sounds are necessary in building syllables.

| → Backness ↓ Height |

Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Oral | i iː | u uː | |

| Br.-voiced | i̤ | ṳ | ||

| High-mid | Oral | e eː | ||

| Br.-voiced | e̤ | |||

| Low-mid | ɛ | ɔ | ||

| Low | Oral | a aː | ||

| Br.-voiced | ɑ̤ | |||

| Diphthongs | Oral | aɪ̯ eɪ̯ eɐ̯ | ɔə̯ | aʊ̯ ɔu̯[3] |

| Br.-voiced | a̤ɪ̯ e̤ɪ̯ | a̤ʊ̯ | ||

| Syllabic consonants | ʀ̩ ʀ̩ː | |||

Allophones of vowels in standard Chlouvānem rarely diverge much from their IPA representation; as Chlouvānem (and most of its descendants, which are the true native languages for the majority of Chlouvānem speakers) are syllable-timed languages, vowels are barely (if at all) reduced in unstressed syllables. The most notable differences are:

- /ɛ/ lowers to [æ] before /ʀ/;

- /ɔ/ is realized as [oː] word-finally (though very rare);

- /u/ is moderately fronted - usually to [ʉ] - after palatalized consonants and /j/ (explaining why /y/ or similar vowels are usually borrowed as /ju/).

Prosody

Stress

Stress in Chlouvānem is not phonemic and usually predictable, determined by long vowels and verbal roots:

- The last long vowel in a word is stressed, unless it is word-final ė;

- Verbal roots always carry either the main stress or secondary stress (depending on the previous rule);

- In words with no long vowels, the third-to-last syllable is stressed, unless the fourth-to-last is the stressed part of a verbal root;

- Compound words have secondary stress on each vowel that would have primary stress if it were an isolated word, except if immediately preceding another (primarily or secondarily) stressed vowel; in that case, the stress moves one syllable backwards unless it would lead to another such situation of consecutive stress (e.g. */ˌSSˌSˈSS/ → /ˌSSSˈSS/ and not **/ˌSˌSSˈSS/).

Some examples of stress placement:

- dilṭha "desert" [ˈdʲiɴ̆ʈʰa]

- upānāraḍa "seminary" [upaːˈnaːʀaɖa]

- ñulge "to crawl (monodirectional)" [ˈɲuŋge]

- ñogė "(s)he/it crawls" [ˈɲogeː]

- ñuganāja "we crawled" [ˌɲugaˈnaːɟ͡ʑa]

- driturkye "[I've been told that] (it) was done against you" [ˈdʀʲituˤkje]

- sågnstrausis "tunnel" [sɔgnˈstʀaʊ̯sʲis]

- sågnstraustammikeika "tunnel railway station" [ˌsɔgnstʀaʊ̯sˌtammʲiˈkeɪ̯ka]

Words with unpredictable stress often have regional variations. For example, tandayena "spring (season)" is stressed as [tandaˈjena] in most of the East and Northeast but as regular [tanˈdajena] almost anywhere else (in this particular case, the irregular stress is actually closer to the etymology, as it is a borrowing from a Kans-Tsan compound word).

Intonation

Phonotactics

The maximum possible syllable structure is 「[((C1)C2)C3]」(j)V「(C4(C5))」.

The nucleus is formed by V - which can be any vowel, diphthong, or syllabic consonant - and an optional preceding /j/.

The onset may contain up to three consonants: C3 is notated differently because phonetically there always is one, as phonemically vowel-initial syllables are always pronounced with a preceding [ʔ]. Any consonant bar /N/ can appear in this position; C2 can be any other consonant except aspirated or breathy-voiced stops (with a single exception) or /ʔ/, but, if C3 is a stop, no stop can be in this position. If C3 is /ɴ̆/ , then C2 may be /c͡ɕʰ/. C1 may be a sibilant, /ʋ/, or a nasal agreeing in PoA with the following consonant. Note that ss-, vv-, ll- and lьl- are all valid onsets under these rules.

In codas, C4 may be may be any consonant except /ʔ c͡ɕ ɟ͡ʑ/ or all aspirated or breathy-voiced stops. C5 may be /n m s/, or also one of /t d k g/ if C4 is one of /ɴ̆ ʀ/.

In absolute word-final position, only C4 is possible, and the only possible consonants are /m n nʲ p t tʲ k s sʲ ɦ ɴ̆ ɴ̆ʲ/. Interjections are an exception, as some other consonants are found there, e.g. hār! "ouch!" [ˈɦaːɐ̯], hųf! "phew!" [ˈɦṳf].

Morphophonology

Vowel alternations

Ablaut

Chlouvānem morphology uses a system of ablaut alternations in its vowels, most notably for some verbs, for the ablauting declension of nouns (5h), and for many derivations. Every normal ablaut pattern has a base grade (the one given in citation forms), a middle grade, and a strong grade.

The patterns of regular ablaut are the following:

- i-ablaut: base i or ī — middle e — strong ai

- u-ablaut: u/ū — o (ą) — au

- u>i-ablaut: u/ū — i — au

- ṛ-ablaut: ṛ — ar — ār

A few roots have the so-called inverse ablaut, where the vowels get simplified in the middle grade, and there is no strong grade:

- i-type inverse ablaut: base ya (or ьa) — middle i

- ei-type inverse ablaut: base ei — middle i

- u-type inverse ablaut: base va — middle u

Lengthening

Lengthening alternations, which originate in Proto-Lahob, substitute a vowel with its lengthened form. There are many apparently irregular cases, due to the huge vowel shifts that happened between Proto-Lahob (PLB) and Chlouvānem. Note that PLB *î represents /ɨ/ or /ɨ̯/.

Lengthening as a type of vowel alternation is the so-called diachronic lengthening, as the results are largely determined by what those vowels were in PLB:

- a → ā

- a → ū (PLB *o → *ō)

- i → ī

- i → æ (PLB *ej → *ēj)

- i → au (PLB *aî → *āî)

- u → ū

- e → ьa (PLB *e → *ē)

- e → ai (PLB *aj → *āj)

- o → au (PLB *aw → *āw)

- o → ei, but → ou after l (PLB *ow → *ōw)

- æ → ьau (PLB *ew → *ēw)

- oe → ai (PLB *oj → *ōj)

- ṛ → ar

Another, different type of lengthening, is synchronic lengthening, which is a saṃdhi change; it only applies to a, i, u, ṛ, and e, turning them into ā, ī, ū, ṝ, and ė respectively.

Vowel saṃdhi

Vowel saṃdhi in Chlouvānem is often fairly logical, though sometimes the results are influenced by Proto-Lahob phonology.

Similar vowels (thus /a i e u ʀ̩/ only diverging in quantity or phonation) merge in these ways:

- short + short = long (e.g. a + a → ā)

- long + short = long (and viceversa) (e.g. ā + a → a)

- oral + breathy-voiced = breathy-voiced (a + ą → ą)

- breathy-voiced + oral = /VɦV/, written with the breathy-voiced character followed by the oral one (e.g. ą + a → ąa)

The only exception to this pattern is the sequence ė + e which becomes ege.

Dissimilar vowels merge in these ways. ṛ and ṝ become semivowels wherever needed, and i and u become y and v before other vowels; ī and ū turn to iy and uv respectively.

Other changes are:

- e and o always continue PLB *aj and *aw regardless of etymology, so when followed by vowels the results are ayV and avV respectively. Similarly, with ai and au the results are āyV and āvV;

- æ and ea both become ev and oe becomes en when followed by another vowel;

- All other ones simply turn their second element into the corresponding semivowel (e.g. ei → ey, but ov → av).

- a: a-i → e ; a-u → o ; a-e → ai ; a-o → au

- ā: ā-i and ā-e → ai ; ā-u and ā-o → au

- a or ā and a following long vowel (or æ or å) get an epenthetic y (before ī, ė, æ) or v (before ū, å).

- When preceded by a, other diphthongs get a prothetic y if their first element is front and a prothetic v if it is back. æ turns to ya.

With present singular exterior verbal terminations, the first person -u gets an epenthetic -v- after vowel-final roots, while second person -i and third person -ė get an epenthetic -y-.

Consonant alternations

Palatalizations

Palatalization in morphemes (noted as ь) produces different results depending on the preceding consonant:

- If the preceding consonant has a phonemic palatalized counterpart, the result is the palatalized consonant (e.g. /t/ + ь → /tʲ/)

- Velars shift to palatals (e.g. k + ь → c);

- h + ь → š

- The glottal stop remains unchanged;

- All other consonants get a /j/ glide (written y).

Internal saṃdhi

Note: for simplicity, ь will be treated as a stand-alone consonant in all the following examples.

Saṃdhi assimilations are fairly straightforward, and usually it’s the second consonant in a row the one that matters. The most basic rules are:

- Nasals assimilate to the PoA of any following consonant except for y (no assimilation occurs) and s (all become ṃ, phonetically realized as vowel nasalization).

- All stops assimilate in voicing to a following stop; if the first one is aspirated, then aspiration shifts to the second one. Dentals also assimilate to adjacent (preceding or following) retroflexes.

In stop saṃdhi, a few further changes apart from basic voicing and retroflex assimilation occur. Note that any such combination also applies to aspirated stops and, for dentals, palatalized ones. In voiceless stops:

-pṭ- → -fṭ- ; -pc- → -ṃc-

-tp- → -tt- ; -tc- → -cc- ; -tk- → -kt-

-ṭp- → -ṭṭ- ; -ṭc- → -cc- ; -ṭk- → -kṭ-

-cp- → -cc- ; -ct- → -kt- ; -cṭ- → -ṣṭ- ; -ck- → -šk-

-kp- → -pp- ; -kc- → -cc-

Doubled stops and the combinations -pt-, -pk- , -kt-, and -kṭ- remain unchanged.

Voiced stops mostly mirror voiceless assimilations (doubling saṃdhi already applied - all nasal + stop clusters are underlyingly a geminate stop):

-bḍ- → -ṇḍ- ; -bj- → -ṃj- ; -bg- → -lg-

-db- → -nd- ; -dj- → -ñj- ; -dg- → -gd-

-ḍb- → -ṇḍ- ; -ḍj- → -ñj- ; -ḍg- → --gḍ- → -rḍ-

-j + any other stop, also aspirated ones → -jñ-

-gb- → -mb- ; -gḍ- → -rḍ- ; -gj- → -ñj-

Doubled stops become a nasal+stop sequence; -bd-, and -gd- remain unchanged.

-d(h)n- and -ḍ(h)ṇ- from any origin further assimilate to -nn- and -rṇ- respectively.

h, wherever it is followed by a consonant (apart from ь), disappears, leaving its trace as breathy-voiced phonation on the preceding vowel (e.g. maih-leilė → mąileilė). Vowels change as such:

- i, ī → į

- u, ū → ų

- e, ė, æ, ea → ę

- all other monophthongs, or oe → ą

- ai, ei, au → ąi, ęi, ąu respectively.

Sibilants trigger various different changes:

- Among themselves, -s s- remains ss (but simplified to s if the latter is followed by a consonant other than y or ь), but any other combination becomes kṣ (e.g. naš-sārah → nakṣārah).

- ṣ, if followed by a dental stop, turns it into ṭ or ṭh according to aspiration (e.g. paṣ-dhokam → paṣṭhokam).

- s or š plus any voiced stop, or ṣ followed by any non-dental voiced stop, disappear but synchronically lengthen the previous vowel (e.g. kus-drāltake → kūdrāltake).

- Dental stops followed by ṣ or š result in a palatal affricate (e.g. prāt-ṣveya → prācveya).

Note that the two roots lih- and muh- behave, before consonants (with a few exceptions, e.g. the verbal infinitive), as if they were *lis- and *mus-.

If the first sound which undergoes saṃdhi is already part of a cluster, a few more assimilations may occur. In a nasal-stop + stop sequence, usually the first stop gets cancelled, but nasals do not assimilate entirely to the stop:

- m becomes ṃ;

- Other nasals do not assimilate at all.

Note that the combinations -mpt-, -mpk-, -lkt-, -lkṭ-, -mbd-, -lgd-, and -lgḍ- all remain unchanged; doubled stops are degeminated (like -mpp- > -mp-).

If the sound before the stop sequence is l or r, nothing happens and assimilations are normal. If the sound is a sibilant (note that they cannot precede voiced stops), assimilations are as usual.

More complex clusters are avoided by means of epenthetic vowels; still, Chlouvānem does feature some long clusters like e.g. /gnstʀ/ in the word sågnstrausis (tunnel)

Doubling saṃdhi

In a few cases of consonant doubling due to saṃdhi, there are irregular results:

- -y y- → -jñ-

- Note that this does not happen in a few morphemes usually with -ai y- (e.g. vīvai-yoṭ- vīvaiyoṭ-), and aiy also happens as a valid root sequence in a few toponyms - like Kaiya (ward of Līlasuṃghāṇa, famous for its artistic buildings and nightlife) or the diocese of Takaiyanta (on the Jade Coast).

- -v v- → -gv-

- -r r- → -rl-

- any doubled voiced stop (also due to assimilation of other stops) → homorganic nasal + voiced stop (e.g. -b b- → -mb-)

Epenthetic vowels

Epenthetic vowels are usually discussed together with saṃdhi. They are often used in verbal conjugations, as no Chlouvānem word may end in two consonants. The epenthetic vowel used depends on the preceding consonant:

- u is inserted after labials;

- e is used after retroflexes (except ṣ), r, and h;

- a is used after ɂ;

- i is used after all other consonants, including all palatalized ones.

Writing system - Jīmalāṇa

Chlouvānem has been written since the late First Era in an abugida called Chlouvānaumi jīmalāṇa ("Chlouvānem script", the noun jīmalāṇa is actually a collective derivation from jīma "character"), developed with influence of the script used for the ancient Kūṣṛmāthi language. The orthography for Chlouvānem represents how it was pronounced in Classical times, but it's completely regular to read in all present-day local pronunciations. The Chlouvānem alphabet is distinguished by a large number of curved letter forms, arising from the need of limiting vertical lines as much as possible in order to avoid tearing the leaves on which early writers wrote. Straight vertical or horizontal lines are in fact present in a few letters (mostly the rarer ones, such as independent vowels) but they have been written as straight lines only since typewriting was invented. Being an abugida, vowels (including diphthongs) are mainly represented by diacritics written by the consonant they come after (some vowel diacritics are actually written before the consonant they are tied to, however); a is however inherent in any consonant and therefore does not need a diacritic sign. Consonant clusters are usually representing by stacking the consonants on one another (with those that appear under the main consonant sometimes being simplified), but a few consonants such as r and l have simplified combining forms. The two consonants ṃ and ь are written with diacritics, as they can't appear alone. There are also special forms for final -m, -s, and -h due to their commonness; other consonants without inherent vowels have to be written with a diacritic sign called priligis (deleter), which has the form of a dot above the letter.

The romanization used for Chlouvānem avoids this problem by giving each phoneme a single character or digraph, but it stays as close as possible to the native script. Aspirated stops and diphthongs are romanized as digraphs and not by single letters; geminate letters, which are represented with a diacritic in the native script, are romanized by writing the consonant twice - in the aspirated stops, only the first letter is written twice, so /ppʰ/ is <pph> and not *<phph>. The following table contains the whole Chlouvānem alphabet as it is romanized, following the native alphabetical order:

| Letter | m | p | ph | b | bh | f | v | n | t | th |

| Sound | /m/ | /p/ | /pʰ/ | /b/ | /bʱ/ | /f/ | /ʋ/ | /n/ | /t̪/ | /t̪ʰ/ |

| Letter | d | dh | s | ṇ | ṭ | ṭh | ḍ | ḍh | ṣ | ñ |

| Sound | /d̪/ | /d̪ʱ/ | /s/ | /ɳ/ | /ʈ/ | /ʈʰ/ | /ɖ/ | /ɖʱ/ | /ʂ/ | /ɳ/ |

| Letter | c | ch | j | jh | š | y | k | kh | g | gh |

| Sound | /c͡ɕ/ | /c͡ɕʰ/ | /ɟ͡ʑ/ | /ɟ͡ʑʱ/ | /ɕ/ | /j/ | /k/ | /kʰ/ | /g/ | /gʱ/ |

| Letter | ṃ | ɂ | h | r | l | ь[4] | i | ī | į | u |

| Sound | /ɴ/ | /ʔ/ | /ɦ/ | /ʀ/ | /ɴ̆/, [ŋ] | /ʲ/ | /i/ | /iː/ | /i̤/ | /u/ |

| Letter | ū | ų | e | ė | ę | o | æ | a | ā | ą |

| Sound | /uː/ | /ṳ/ | /e/ | /eː/ | /e̤/ | /ɔ/ | /ɛ/ | /a/ | /aː/ | /ɑ̤/ |

| Letter | ai | ąi | ei | ęi | ea | oe | au | ąu | å | ou |

| Sound | /aɪ̯/ | /a̤ɪ̯/ | /eɪ̯/ | /e̤ɪ̯/ | /eɐ̯/ | /ɔə̯/ | /aʊ̯/ | /a̤ʊ̯/ | /ɔ/ (see below) | /ɔʊ̯/ |

| Letter | ṛ | ṝ | ||||||||

| Sound | /ʀ̩/ | /ʀ̩ː/ |

Some orthographical and phonological notes:

- /n/ [ŋ] is written as <l> before <k g kh gh n>. Note that in many local varieties <lk lkh lg lgh> are actually [ɴq ɴqʰ ɴɢ ɴɢʱ], with the stop assimilating to <l> and not vice-versa, and thus analyzed as /ɴ̆k ɴ̆kʰ ɴ̆g ɴ̆gʱ/.

Letter names are formed following these simple rules, which depend by phoneme type:

- Voiceless unaspirated stops and fricatives are phoneme + /uː/ (pū, tū, fū, sū...) except for <ɂ> which is aɂū. Voiceless aspirated stops are phoneme + /au̯/ (phau, thau...).

- Voiced unaspirated stops and fricatives are phoneme + /iː/ (bī, vī, dī...), while aspirated ones use /ai̯/ (bhai, dhai...). This latter diphthong is also used for yai, hai, and lai.

- Nasals and <r> use /ei̯/ (mei, nei, rei...), but <ṃ> is, uniquely, nālkāvi.

- Short unrounded vowels are vowel + /t/ + vowel (iti, ete...); short rounded ones have /p/ instead of /t/ (upu, opo).

- Long vowels are vowel + /n/ if unrounded (īn, ėn, ān), or /m/ if rounded (ūm). Oral diphthongs all have diphthong + /m/ + first element (aima, eime...).

- Breathy-voiced vowels are vowel + /ɦ/ + vowel (įi, ųu, ęe, ąa). Breathy-voiced diphthongs are diphthong + /ɦ/ + oral second element (ąihi, ęihi, ąuhu).

o and å

In today's standard Chlouvānem, the letters o and å are homophones, being both pronounced /ɔ/: their distribution reflects their origin in Proto-Lahob (PLB), with o deriving from PLB *aw and *ow, and å from either *a umlauted by a (lost) *o in a following syllable, or, most commonly, from the sequences *o(ː)wa, *o(ː)fa, *o(ː)wo, or *o(ː)fo.

Most Chlouvānem sources, however, classify å as a diphthong: Classical Era sources nearly accurately describe it as /ao̯̯/, later monophthongized to /ʌ/ or /ɒ/ and merged with /ɔ/ - in fact, most daughter languages have the same reflex for both o and å.

It should be noted that in the present day a spelling-based difference between those two letters is becoming more common: in Līlasuṃghāṇa å is increasingly often /oː/, and this is spreading in many other areas - due to mass media influence, there's not a true areal pattern; while it is spreading faster in major urban areas (e.g. in Cami, about 3500 km away from Līlasuṃghāṇa) not all of them do, including some of the closest ones (e.g. Līṭhalyinām, 450 km south of the capital).

Notes on romanization

The romanization here used for Chlouvānem is adapted to English conventions, with a few adjustments made to better reflect how written Chlouvānem looks on Calémere:

- Even if the Chlouvānem script uses scriptio continua and marks minor pauses (e.g. comma and semicolon) with a space between the sentences and a punctuation mark with following space, every word is divided when romanized, including particles. The only eẋceptions to this are compound verbs, which are written as a single word nevertheless (e.g. yųlakemaitiāke "to be about to eat" not *yųlake maitiāke). English punctuation marks are used in basic sentences, including a distinction between comma and semicolon. In longer texts, particularly in the "examples" section, : will be used to mark a comma-like pause (a space in the native script) and ।। will be used for a full-stop-like pause (written very similarly to ।। in the native script).

- As the Chlouvānem script does not have lettercase, no uppercase letters are used in the romanization, except to disambiguate cases like lairė (noun: sky, air) and Lairė (female given name), and for proper nouns written in isolation.

Morphology - Maivāndarāmita

→ Main article: Chlouvānem morphology

Chlouvānem morphology (maivāndarāmita) is complex and synthetic, with a large number of inflections. Six parts of speech are traditionally distinguished: nouns, adjectives, verbs, pronouns, numerals, and particles.

Syntax

Constituent order

Like most other Lahob languages, the preferred word order in Chlouvānem is SOV, and the language is almost completely head-final. The word order could however be better defined as topic-comment, but in less common styles it is perfectly possible, thanks to case inflections, to greatly deviate from this standard order.

The subject - whatever agrees with the verb - is usually the topic, but there can be another explicitely stated topic (denoted by the particle mæn) which gets precedence on the subject (triggered by the verb), as in the third of the following examples:

- yąloe lį ulguta - The food has been bought by me. (food.DIR.SG. 1SG.ERG. buy.PERF-3SG.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.)

- lili yąlenu ulgutaṃte - I have bought food. (1SG.DIR. food-ACC.SG. buy.PERF-1SG.EXTERIOR-AGENT.)

- liliā ñæltah mæn yąloe lį ulguta - My sister, I bought the food [for her]. (1SG.GEN. sister.DIR.SG. TOPIC. food.DIR.SG. 1SG.ERG. buy.PERF-3SG.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.)

The topic-comment structure of Chlouvānem sentences is an analysis that derives from the fact that, in normal speech, the subject always comes first in the sentence except for unmarked topics, or temporal complements topicalized through word order, as in:

- flære prājamne lili lārvājuṣom pīdhvu.

- yesterday. evening-LOC.SG. 1SG.DIR. temple-DAT.SG. go.MULTIDIR.PAST-IND.1S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.

- Yesterday [in the] evening I went to the temple.

Use of the topic

The topic is explicitely marked with mæn if it does not coincide with the subject and does not have any syntactical role in the sentence. Some common structures where explicit topics are always used rank among the most basic sentences:

- lili mæn māmimojendeh fliven "I am 21 (1912, Chlouvānem age)/20 years old (English age)"[5], glossed: 1SG.DIR. TOPIC. nineteenth12.PARROT.DIR.SG. go.MONODIR-IND.PRES.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.

- lili mæn ñæltion unde "I have two sisters", glossed 1SG.DIR. TOPIC. sister-DIR.DUAL. be-IND.PRES.3D.EXTERIOR.PATIENT. — the verb "to have" is always translated by this construction.

- lili mæn kite domani tītya [ulīran] "in my house there are eight rooms", glossed 1SG.DIR. TOPIC. house-LOC.SG. room-.GEN.SG. eight. [be-IND.PRES.3P.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.]

Two different topics are also commonly used in contrasts:

- rūdakis mæn tadadrā lili mæn yąlė "[my] husband has cooked, but I eat" - husband.DIR.SG.TOPIC. prepare.IND.PERF.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT. 1SG.DIR. TOPIC. eat-IND.PRES.1S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.

Note how neither "husband" nor "I" agree with the verbs, and note how different formulations change meanings:- rūdakis mæn tęvis tadadrā lili mæn yąlė - main interpretation: "as for the husband, he [=someone else, could be the husband's husband] has cooked for him, but it is me who eats" // other possible interpretation: "as for the husband, he [=as before] has cooked him, but it is me who eats / and I eat him [=either of them]".

- rūdakis mæn tadadrā sama lili yąlute "[my] husband has cooked, and I eat" - unlike in the sentence where "lili" is the topic, here it's explicit that the husband cooked for the speaker. The sentence lili mæn rūdakei tadadrā sama yąlute may be interpreted with the same meaning, but the topics are different: with the previous one, the conversation is supposed to continue about the husband; in the second one, it's all about the speaker. Note that the agent-trigger voice in the second verb is of vital importance: the sentence lili mæn rūdakei tadadrā sama yąlu means "it is me my husband has cooked, and [now] he eats me".

- Another possible interpretation of lili mæn rūdakei tadadrā sama yąlute is "[my] husband has cooked for me, and now I eat", which is the same as lili rūdakei takædadrā sama yąlute, but the latter is a plain neutral statement.

Topics also mark context: as a good example, the Chlouvānem translation of Schleicher's fable begins as: yanekai mæn bhadvęs udvī leilam voltām mišote, ūtarnu cūllu khulьsusu, spragnyu ūtrau dumbhasusu no, lilu kimęe dumbhasusu no. Here "horses" is the topic and has no syntactical role in the sentence, as the subject is the agent voltām (sheep) and the three objects are the patients khulьsusah (the pulling one) and two different dumbhasusah (the carrying one). The topic makes it clear that these latter are nouns referring to horses - it would still be grammatical to use [...] khulьsusu yaneku, spragnyu ūtrau dumbhasusu yaneku no, lilu kimęe dumbhasusu yaneku no, but the sentence would sound strange to Chlouvānem ears - compare the possible English translation "[...] a sheep saw one horse that was pulling a heavy wagon, one horse that was carrying a big load, and one horse that was carrying a man quickly".

As such, topics usually avoid repetition and anaphora, acting much like folders where different paper sheets (= the sentences) are contained, e.g. nāmñė mæn švai chlouvānumi maichleyutei, jariāmaile lilah, soramiya mušigėrisilīm tora bu sama ñikumi viṣam haloe līlas væl. nenėhu līlasuṃghāṇa ga camimarti haloe gṇyāvire - "talking about nāmñai[6], [they're] animals of the Southern [part of the] Chlouvānem lands, [they] live in seawater but sometimes [they can be found] in tidal lakes too, and another name for [their] cubs is "līlas". From this [name] comes the name of the capital, Līlasuṃghāṇa."

Finally, certain sentences act as answers for different questions due to different implications depending on whether there's an explicit topic or not:

- lili mæn lunai tadarė "I'm preparing tea", topicalized, clearly answers a question like yananū ejulā darire? "what's going on here?".

- lili lunāyu tatedaru "I'm preparing tea" answers yavita lunāyu tatedarė? "who is preparing tea?", with the meaning of "no one but me is preparing tea".

- With a question like yananū sąi darė? "what are you doing?", both become synonyms as they introduce the new topic lili (due to the previous one being yananū? because of patient-trigger voice); the same question in agent-trigger voice, sāmi yananūyu darite?, would be answered with the non-topicalized form.

Noun phrase

Non-triggered arguments

Non-triggered arguments require a specific case to distinguish their role when they're not triggered by the voice:

- Patient → accusative case

- Agent → ergative case

- Benefacted → direct + nali

- Antibenefacted → direct + fras

- Location → locative case

- Instrument → instrumental case

- Dative argument → dative case

Stative cases as nominal tense

The three stative cases of Chlouvānem (translative, exessive, essive) express nominal tense in certain situations, most notably in copulative sentence, where the translative case conveys a future meaning and the exessive a past one:

- lili rahėllilan — I am a will-be-doctor = I am studying in order to become a doctor

- liliā kaleya mæn gu ninejñairau ša nanū aveṣyotāran lallāmahan camimurkadhānan gīti — as for my best friend[7], I could not believe it, that she was the Great Inquisitor-elect (note the use of the highly respectful (not translated) formula "Her Most Excellent Highness, the Great Inquisitor").

- tami tamiāt šulañšenat — he is her former husband.

The expression of tense is also notable when the expression of state refers to a cause; this is particularly common with the exessive and essive cases:

- saminat tamiā ḍhuvah — having been a child (lit. "as a former child", "from being a child"), (s)he remembers that.

- lūlunimartyęs nunūt dældāt tarliru — being from Lūlunimarta, I understand that language. Note that nunūt dældāt here is exessive case but only because it's an argument of the verb tṛlake, without implying tense.

- bunān samin pa maišildente — as he's going to be a father (lit. "as a will-be-father"), he's learning about children.

Note that, like for participles, tense is relative to the main verb.

Miscellaneous uses of cases

Purpose may be expressed not only with a subjunctive verb, but also with either a translative or a dative noun.

Translative case is used generally with a purpose directly affecting the trigger:

- murkadhānan kaminairīveyu. "I am studying [in order to become] an Inquisitor."

- tąsь lapi nadaidanan peithegde. "(s)he is going out with him/her to get to know him/her."

Dative case is used generally when the purpose is something else, or is the result of a subsequent (unstated) action:

- maivnaviṣye maivauti khloute. "I am searching in the dictionary [in order to find] the words."

- lgrån mayābyom rāmīran. "Grapes are harvested for wine." (Wine is not the direct result of harvesting, thus dative is used instead of translative).

Ablative case is used in order to state comparisons:

- dāneh dulmaidanų nanū lalla. "Dāneh is taller than Dulmaidana."

- faliā ñæltah tąu chloucæm pūnė. "Your sister works better than him/her."

- nenė naviṣya yaivų nanū ñæñuchleh. "This book is the most beautiful." (literally "more beautiful than all")

It is also used as reason when it's an abstract noun:

- tami kairų hånyadaikah moe. "(s)he was happy for love."

- maidaudių ḍūkirek. "(s)he died because of his/her ambition."

Possession may be also expressed with the genitive case (topic marking is the most common way, but in some cases this may be needed syntactically; there is a verb cārake translating as "to have, possess", but it's fairly literary and high-styled). "To be" may or may not be present:

- kvyāti giṣṭarah lalāruṇa (væl) "The hero has a young lalāruṇa." (literally "of the hero is the young lalāruṇa")

- pogi gu cūllanagdha "My village does not have a velodrome." (literally "of my village is no velodrome")

Verb phrase

Use of tenses: Past vs. Perfect

Past and perfect are the two Chlouvānem (morphological) tenses that are used to refer to past actions. Their meanings may be summarized this way:

- The past tense always refers to the past, but it isn’t always perfective;

- The perfect “tense” is always perfective, but it isn’t always past - and when it does, it has an impact on the present.

These theoretical meanings may be translated into practice as this: the past is most commonly used to express something that happened in the past and does not influence the present, or it is not meaningful to the time of the action.

- tammikeika flære lį yųlekpan.

- train_station.DIR.SG. yesterday. 1SG.ERG. eat-IND.PAST.3S.EXTERIOR-LOC.

- Yesterday I ate at the station.

- palias jāyim junirek.

- face.DIR.SG. girl.DIR.SG. paint-IND.PAST.3S.INTERIOR.

- The girl painted her [own] face.

In an appropriate context, however, the same verb form can carry an imperfective meaning:

- tammikeika flære lį yųlopan væse, nanā tammi tadāmek.

- train_station.DIR.SG. yesterday. 1SG.ERG. eat-IND.PAST.3S.EXTERIOR-LOC. while. , that.DIR.PARROT. train.DIR.SG. arrive-IND.PAST.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR

- Yesterday I ate at the station.

- jāyim mæn palias junirek, mbu nenichladireti meinei muṣkemālchek.

- girl.DIR.SG. TOPIC. face.DIR.SG. paint-IND.PAST.3S.INTERIOR. , but. hurry-SUBJ.IMPF.3S.INTERIOR. mother-ERG.SG. ask-INF-run.MULTID-IND.PAST.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR.

- The girl was painting her [own] face, but her mother kept asking her to hurry.

Generally this imperfective meaning is assumed by other words in the sentence, usually væse (while), but commonly also mbu (but) with a related sentence understood to be imperfective. Out of context, imperfective past is usually expressed with an analytic construction:

- tammikeika flære lį yųlasusąpan moe.

- train_station.DIR.SG. yesterday. 1SG.ERG. eat-PART.PRES.EXTERIOR-PARROT.DIR-LOC. be.IND.PAST.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR.

- Yesterday I was eating at the station.

The main use of the perfect is expressing something that happened in the past but is still impacting the present; this is a difference very similar to the one between simple past and present perfect in English, and as such the perfect is usually translated that way. Compare, for example:

- palias jāyim junirek - “the girl painted her [own] face”. Past tense here expresses a generic action: the girl may have painted her face ten years or five minutes ago, but that is irrelevant to the situation. In this particular sentence, the girl’s face may be understood to have now been cleaned, or that she may have cleaned and painted her face again many times - but, actually, whether she did or didn’t is now irrelevant. The actual time when she did it only becomes relevant if it is expressed (e.g. palias jāyim flære junirek “the girl painted her [own] face yesterday”) and then it is understood that her face isn’t painted anymore.

- palias jāyim ujunirā - “the girl has painted her [own] face”. Perfect “tense” here focusses not on the action, but on its result. The girl finished painting her face, and it may be seen that her face is still painted - when she did is still irrelevant, but it happened sufficiently close in time that the result of that action may still be seen.

The Chlouvānem perfect, however, has a broader use than the English one, compare:

- flære dašajildek - “yesterday it rained”. Past tense, implied meaning is that there’s nothing that may indicate that yesterday it rained, or it doesn’t influence the speaker in any way.

- flære dašejilda - *yesterday it has rained. Perfect tense; while wrong in English, this construction is possible - and, in fact, is frequently heard - though it often only makes sense in a broader context. For example, in a sentence like “yesterday it rained and the path collapsed, so we [two] can’t walk there”, English uses both times a simple past, while Chlouvānem uses the perfect, as the path is still not walkable due to the rain: flære menni dašejilda līlta viṣeheṣṭvirā no, āñjulā gu pepeithnāyou ša.

Note that the “impact on the present” meaning and the use of evidentials are independent from each other. Using a first inferential, for example, does not change the implications given by the use of perfect or past, though the actual interpretation is often heavily dependent from context:

- palias jāyim junirekvan - “apparently, the girl painted her [own] face”. Past tense: it can be assumed that the girl painted her own face sometime in the past; e.g. the girl is now painting her face, and given the way she does it, it’s reasonable to believe it’s not her first time.

- palias jāyim ujuniritena - “apparently, the girl has painted her [own] face”. Perfect “tense”: it can be assumed that the girl now has a painted face, but the speaker has not seen her; e.g. in her room there are face painting colours open or that look like they’ve been recently used.

Second inferential changes the speaker’s deduction, but not the implications given by tenses:

- palias jāyim junirekvammū - “apparently, the girl painted her [own] face, but probably didn’t”. Past tense: as before, but while she, or something she did, had made the speaker believe she had already painted her face at least once in the past, the way she’s doing it makes think that she probably never did.

- palias jāyim ujuniritenamū - “apparently, the girl has painted her [own] face, but probably didn’t”. Perfect “tense”: as before; highly dependent on context. For example, there are face painting colours out of place, but it’s unlikely she did paint her face - e.g. it may not be a logical time to do it, or too little colour seems to have been used.

The Chlouvānem perfect is however also used where English would use past perfect or future perfect, as the “impact on the present” is understood to be on the time the main action in the sentence takes place, thus something that happened earlier is considered to have an impact on it:

- tammikeika flære lį uyųlapan, utiya nanā tammi tadāmek.

- train_station.DIR.SG. yesterday. 1SG.ERG. eat-IND.PERF.3S.EXTERIOR-LOC. , then. that.DIR.PARROT. train.DIR.SG. arrive-IND.PAST.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR.

- I had [already] eaten at the station yesterday when the train arrived.

- tammikeika lį uyųlapan, utiya nanā tammi tafluniṣya.

- train_station.DIR.SG. 1SG.ERG. eat-IND.PERF.3S.EXTERIOR-LOC. , then. that.DIR.PARROT. train.DIR.SG. arrive-IND.FUT.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR.

- I will have [already] eaten at the station when the train arrives.

Note that in the latter example, English uses future perfect and present simple respectively, while Chlouvānem uses perfect and future; the future in the second clause is necessary to give the future perfect meaning to the first one.

Still, note that out of context both pluperfect and future perfect may be expressed analytically, by using the perfect participle plus the past or future tense of gyake (to be).

A notable exception to this use is with so-called “chained actions”, when the second one is a direct consequence of the first and the first one is usually still ongoing; the second one is therefore only a momentane happening inside the broader context of the first, and thus the choice between present and past is once again dependent on the impact on the present. Note that in such cases the two verbs are usually connected with no instead of sama. Compare:

- dašajildo līlta vīheṣṭvirek no - “it rained, and the path collapsed”. Past tense: the path has since been repaired and it is walkable.

- dašejilda līlta viṣeheṣṭvirā no - “it has rained, and the path has collapsed”. Perfect “tense”: the path is not walkable due to it having collapsed.

Both the past and the perfect are independent from verbal aspect:

- marte mīmīšviyek kite lįnek no - "(s)he kept being seen in the city, and [therefore] remained at home" ((s)he has since gone out of home).

- marte mīšimīšveya kite ilįna no - "(s)he has kept being seen in the city, and [therefore] she has remained at home" (actual meaning dependent on a broader context, e.g. āñjulā tatantepepeithnaiṣyes "you can find him/her there" (potential agent-trigger future of tatāpeithake (ta-tad-peith-) "to find (frequentative)")).

The optative mood

The Chlouvānem optative has two main uses: as an expression for wishes (in exclamations), and as a form roughly corresponding to the English verbs "should" and "ought to". Due to these meanings, it is also a common form of polite imperative.

The use of optative forms, given this explanation, is fairly clear; some examples follow.

- tami paṣalīleinė! "may (s)he survive!"

- pū glidemæh āñjulā jeivau! "if only I had been there!"

- samin nanea domane gu tiaineran ša. "the kids shouldn't stay in that room."

- yąlenų ānat kārvātiu valtfårsadreinite. "after a meal you ought to burn (lit. "to turn on") incense[8]."

- lālis yacė nami, tamaireinildṛši spa. "please sit down."

The subjunctive mood

The subjunctive mood has a variety of uses, most commonly when followed or introduced by a certain particle. The bare subjunctive, however, has a supine meaning:

- šuteitieldā, yaivei tamišīti. "it has been put there for everybody to look at it."

- luvāmom dāmek yambrānu lgutītite. "(s)he went to the market to buy pears."

Some verbs, such as nīdhyuʔake (to call for), usually require the subjunctive:

- nītedhyuʔek karthāgo bīdrīti. "(s)he called for Carthage to be destroyed."

The verbs for "to study" (pāṭṭaruke, pāṭṭarudṛke, kaminairīveke) and "to learn" (interior forms of mišake; nairīveke) only need a supine-meaning subjunctive when they mean "in order to know something, in order to be able to". With the meaning "in order to become something", a noun in translative case is used:

- fildenī āndṛke munatiam ejulā kaminairīveyu. "I study here in order to be able to create games."

- fildenāndarlilan kaminairīveyu. "I study in order to become a game creator."

Verbs like lelke (to choose (stem: len-)), its synonym vāgdulke (vād-kul-), or mulke (to know how to (stem: mun-, highest grade ablaut in the present) can use invariably the subjunctive or the infinitive; usually, the subjunctive is used when there is a stated subject that is different from an impersonal phrase:

- tami jilde maunalieh. "we know how to do it."

- yakaliyātamei āndrīti elena. "it has been chosen to have it built by Your honorable company."

- tami šubīdṛke lenanājate. "we decided to tear it down."

Positional verbs

Positional verbs are among the most complex features of Chlouvānem grammar. In order to build verbs such as "to stay", "to be seated", and "to lie", Chlouvānem uses a base which is then prefixed with a locative particle, building verbs meaning "to stay on", "to stay under", "to stay in", and so on. There are 26 prefixes for each of the three verbs:

| Prefix | To stay (tiā-/tim-) | To be seated (mirt-) | To lie (ut-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generic position (ta-) | tatiāke (tatimu; tatimau; taʔatimum) |

tamirte (tamertu; tamirtau; temirtim) |

tokte (tautu; totau; toʔutim) |

| On(to), above (ān-) | āntiāke | āmmirte | ānukte |

| Under, below (šu-) | šutiāke | šumirte | šūkte |

| In the middle of, between (khl-) | khlatiāke | khlumirte | khlukte |

| Together with, among (gin-) | gintiāke | gimmirte | ginukte |

| Within inside (nī-) | nītiāke | nīmirte | nyukte |

| Near (ū(b)-) | ūtiāke | ūmirte | ūbukte |

| Far (bis-) | bistiāke | bismirte | bisukte |

| Physically attached; mounting an animal/a bike (tad-) | tandiāke | tadmirte | tadukte |

| Hanging from; upside down (įs-) | įstiāke | įsmirte | įsukte |

| In(to), inside (na(ñ)-) | natiāke | namirte | nañukte |

| Outside, outwards (kau-) | kautiāke | kaumirte | kavukte |

| Opposite to; somewhere else (viṣ-) | viṣṭyāke | viṣmirte | viṣukte |

| Around (kami-) | kamitiāke | kamimirte | kamyukte |

| Behind (prь-) | pritiāke | primirte | priukte |

| In front of (mai-) | maitiāke | maimirte | mayukte |

| In a corner; on a border; at the limits of (vai-) | vaitiāke | vaimirte | vayukte |

| Next to; alongside (ėle-) | ėletiāke | ėlemirte | ėlayukte |

| In the center of (lā(d)-) | lātiāke | lāmirte | lādukte |

| On the left (vyā-) | vyātiāke | vyāmirte | vyokte |

| On the right (māha-) | māhatiāke | māhamirte | māhokte |

| Facing; towards (pid-) | pindiāke | pidmirte | pidukte |

| Facing inside; near the center; mot.: convergent (nalь-) | nalьtiāke | nalьmirte | naliukte |

| Facing outside; far from the center; mot.: divergent (vād-) | vāndiāke | vādmirte | vādukte |

These basic forms have static meanings, and are always intransitive exterior verbs.

Their causative forms translate the English verbs "to put", "to seat" and "to lay" respectively, and are transitive when exterior and intransitive (middle) when interior. Verbs equivalent to English to remain are formed by attaching these prefixes to the verb lįnake for the analogues of -tiā/-tim (e.g. tatiāke → lįnake; āntiāke → āṃlįnake; šutiāke → šulįnake and so on), while for the others (to remain seated; to remain lying) the construction lįnake + positional infinitive is used (e.g. tamirtelęnu "I remain seated").

Note that -tiā verbs all have their basic (present/imperative, subjunctive, hypothetical) stem in -tim-: tatimu, ėletimu, kautimu...

These verbs all use two different place arguments: actual position, which requires locative case, and relative position, requiring exessive case. The latter often denotes non-inclusion in the mentioned place. Some examples:

- jñūmat māhatimu.

tree-EX.SG. stand.right.of.IND.PRES-1SG.EXT.PATIENT.TRG.

I'm standing to the right of the tree. - domañe vaimertu.

room-LOC.SG. be.seated.in.corner.IND.PRES-1SG.EXT.PATIENT.TRG.

I'm sitting in a corner of the room. - domanat vaimertu.

room-EX.SG. be.seated.in.corner.IND.PRES-1SG.EXT.PATIENT.TRG.

I'm sitting in a corner outside the room. - jñūmat ūnime priotu.

tree-EX.SG. street-LOC.SG. lie.behind.IND.PRES-1SG.EXT.PATIENT.TRG.

I'm lying in the street, behind the tree.

Positional prefixes as derivational affixes

Positional prefixes are commonly used as derivational affixes, often with only a figurative representation of the positional meaning. Some examples:

- mai- (in front of) is often used for something done in advance, or to someone. It is also used for iteratives (e.g. maimilge "to keep hearing" (but also "to hear in advance"))

- ān- (above) and na(ñ)- (in, inside) may be used as intensives (but cam- is more common) or inceptives.

- šu- (down, below) (and also kau (outside), especially for states) may be used with a terminative meaning.

The root męlь- (to give) is a good example for this: from the basic verb męlike we can find derivations such as primęlike (to give back (exterior), to return (interior)), maimęlike (to prepare), āmmęlike (to dedicate oneself (mentally) to), namęlike (to dedicate oneself (physically) to), or šumęlike (to renounce). An inceptive/terminative pair is pugle (to sleep) → nampugle (to fall asleep) and kaupugle (to wake up).

Positions without positional verbs

Positional prefixes may be used to express positions without position verbs. There are three possible strategies.

The morphologically easiest is to simply attach the positional prefix in front of the verb and express that position with the locative, so for example we have:

- lilea domane nateyašu "I read in my room".

- lilea domane natekillieh "we talk in my room".

However, while always correct, there may be some ambiguities because of the use of positional prefixes as derivational ones: the latter example shows one of these ambiguities, as nakulke means both "to talk (in somewhere)" and "to begin to talk/speak". Another strategy, correct but more proper in formal writings than in speech, is to use the appropriate positional verb as a homofocal adverbial. This has the advantage of showing the type of position:

- lilea domane nañollie yašute "I read while laying in my room" (note that "to lay in one's room" idiomatically means "to lay on the bed").

- lilea domane namerlie killięte "we talk while sitting in my room".

The third, and most colloquial strategy, is to put the position as the derived noun (in -timas / -mirtas / -utis) in the locative and the location in the genitive:

- liliai domani nañutie yašute "I read while laying in my room" (lit. "in a sitting position in the inside of my room").

- liliai domani namirte killięte "we talk while sitting in my room".

Note that some locations are often expressed with the last one anyway, especially if they're idiomatic — a notable example being yųljavyī ūtime/ūmirte "standing/sitting in the kitchen", as yųljavyāh originally meant "fire for [cooking] food" and while it later was extended to "kitchen" the location is still expressed as such ("in the kitchen" = "near the fire").

Motion verbs - Duldaradhūvī

Along with positional verbs, motion verbs (sg. duldaradhūs, pl. duldaradhūvī) are another complex but essential part of Chlouvānem grammar. Motion verbs can be monodirectional (tūtugirdaradhūs, -ūvī) or multidirectional (tailьgirdaradhūs, -ūvī), and all verbs come in pairs, each member of a pair being used in different contexts.

Historically, most of the multidirectional verbs (except the "suppletive" peithake, pūrṣake, and dulde) have been derived as iterative forms of the original Proto-Lahob verbs (continued by the monodirectionals), as in PLB *mudʱ- → mudh- vs. *máw-re-dʱ- → mordh-.

The motion verbs of Chlouvānem are:

| Meaning | Monodirectional verb (root) | Multidirectional verb (root) |

|---|---|---|

| to go, to walk | flulke (flun-) | peithake |

| to go with a vehicle (trans.) (except small boats, bikes, and airplanes) |

vaske | pūrṣake |

| to ride, to mount (trans.) | nūkkhe (nūkh-) | nærkhake |

| to go towards, to be directed to (monodir.) to move (multidir.)[9] |

girake | dulde (duld-) |

| to run | mṛcce | mālchake |

| to swim | lįke | lærṣake |

| to fly | mugdhe (mudh-) | mordhake |

| to float in the air to go with a balloon or zeppelin |

yaṃške (yaṃš-/iṃš-) | īraške |

| to float on water to go with a small boat, to row |

uṭake | arṭake |

| to run (trans.) (e.g. river, water)[10] |

buñjñake | — |

| to roll | pṝke | pārlake |

| to climb | nittake | nėrpake |

| to jump | mųke | mårṣake |

| to crawl | ñulge (ñug-) | ñoerake[11] |

| to fall | heṣṭvake | — |

| to carry, bring (on foot) (trans.) | dumbhake | dårbhake |

| to carry, bring (using a vehicle) (trans.) | tulьje | lerjike |

| to pull (trans.) | khulike | kharliake |

Monodirectional verbs are used when there's movement in a single direction, or when the destination is the focus of the verb:

- jāyim tarlāmahom fliven - the girl walks to school.

- keikom vasau - I went to the park [using a vehicle].

- liliā ñæltai kitom jaje janāyų iliha - my sisters have swum home in the igarapé from the port.

This last example shows all three cases used for location complements: dative (in lative use) for directions (= tarlāmahom, keikom, kitom), locative for where the action takes place (jaje), and ablative for origins (janāyų).

Multidirectional verbs have different uses:

- Generic or habitual actions:

- jāyim tarlāmahom peithė - the girl regularly walks to school.

- saminą liliā ñæltai jaje lærṣayivė - when they were children, my sisters regularly swam in the igarapé.

- Movement inside a specific location (in locative case, or expressed through locative trigger voice), without any specified direction:

- marte peithalieh - we walk around the city.

- jaja lærṣėpan - as for the igarapé, someone is swimming in there.

- Gnomic or potential meanings:

- gūṇai mordhīran - birds [can] fly.

- spragnyæh lalāruṇai pāmveh lilu en nanū dårbhīrante - large lalāruṇai can carry more than three people.

- (in the past or perfect) completed movements: movement to a place and then returning back.

- liliā buneya galiākinom mordhek - my older sister went to Galiākina by plane [and came back].

- liliā buneya galiākinom mudhek - my older sister went to Galiākina by plane [but she's still there {or at least she was at the time relevant to the topic}].

Except for this last meaning, multidirectional verbs are never used in the perfect.

In auxiliary constructions, monodirectional verbs are never used as habituals (infinitive + ñeaʔake), while multidirectional ones are never used as progressives (p.part + gyake):

- liliā buneya galiākinom mordhakeñeaʔek - my older sister regularly went to Galiākina by plane.

- liliā buneya galiākinom mugdhyąte moe - my older sister was flying to Galiākina.

Origin prefixes

Positional prefixes are used with motion verbs in order to more specifically state direction; as they get a directional meaning, most of these prefixes also have a corresponding origin prefix:

| "Lative" prefix | "Ablative" prefix | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| ta- | tų- | Generic direction |

| ān- | yana- | Above |

| šu- | šer- | Under |

| khl- | kelь- | In the middle of, together with |

| gin- | ją- | In a group; among |

| nī- | ani- | Within inside |

| ū(b)- | yom- | Near, close |

| bis- | bara- | Far |

| tad- | tasi- | Attached to; on an animal |

| įs- | hos- | Hanging |

| na(ñ)- | neni- | Inside |

| kau- | kuvi- | Outside |

| viṣ- | vyeṣa- | Opposite; somewhere else |

| kami- | kįla- | Around |

| prь- | paro- | Behind |

| mai- | mīram- | In front of |

| vai- | vea- | In a corner |

| ėle- | ora- | Next to |

| lā(d)- | lo(d)- | In the center |

| vyā- | veši- | Left |

| māha- | mege- | Right |

| nalь- | (vād-) | Convergent, inwards |

| vād- | (nalь-) | Divergent, outwards |

| be- | ter- | On the surface |

| gala- | hali- | Through |

| naš- | — | Completely, to the end |

| paṣ- | Further ahead, beyond | |

| sam- | Towards the next (object/goal) | |

| vod- | Avoiding |

These verbs have a peculiarity, as all prefixes except for ta-/tų- make the verb transitive but with a default “common” voice: that is, the agent-trigger is not marked on the verb and only case makes it clear:

- jāyim ñariū āmfliven “the girl walks up the mountain” (agent-trigger)

- ñariah jāyimei āmfliven "the mountain is walked up by the girl" (patient-trigger)

Other examples are:

- jñūm prifliven "someone goes behind the tree" (lit. *the tree is being gone behind)

- lālia ñæltah kitu yomfluṃsusah "my sister is approaching from home"

When there is a prefix expressing relative position and one expressing direction, the most important one is always the one closest to the root; the other one (usually the relative position) is normally expressed with the appropriate case, as in the verb vodūmṛcce "to run nearer (to something) while avoiding (something else)":

- sāmiā kita nanāt ūnimat vodūbamṛca "your house has been approached by running while avoiding that street".

Arguments usually change from the non-prefixed forms: for example vaske (to drive) is transitive and its patient is the means of transport, while the patient of khlavaske (to go with [by vehicle]) is the person with whom the agent goes.

ta-/tes- prefixed verbs are always intransitive, and the transitive forms may be done only by deriving an additional applicative verb (usually mainly a stylistic exercise in poetry), as in taflulke "to arrive (on foot)" → nartaflulke "to reach (on foot)":

- jaṃšom taflå "I arrive to the party"

- jaṃšā nartafliven "the party is [being] reached"

To wear, put on, take off

Chlouvānem does not have a single verb for "to wear", "to put on", or "to take off" when related to clothing: instead, there are seven different verbs depending on the part of the body for "to wear" and "to put on", and seven more (paired with these) for "to take off".

Despite the apparent complexity of such a system, they are completely regular and built in a logical way, with "lative" prefixes for the wear/put on verb and "ablative" for the take off one:

| Clothing type/body part | To wear/to put on | To take off | Related root |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any clothing bandaged around the body, plus most things worn around the trunk (Most generic verb, but does not cover all other meanings) |

kamikyāke | kįlakyāke | ukyā "trunk" |

| Shoes, socks, anything else on the feet and/or ankles | kamijunaike | kįlajunaike | junai "foot" |

| Head and neck (hats, caps, tiaras, necklaces...) | āṃlāṇṭake | yanalāṇṭake | lāṇṭam "head" |

| Hands, wrists (gloves, bracelets...) | kamidhānake | kįladhānake | dhāna "hand" |

| Legs (except bandaged-around clothing that also covers the trunk) Trousers, pants |

nampājike | nenipājike | pājya "leg" |

| Something with (long) sleeves | āṃskaglake | yanaskaglake | skaglas "blanket" |

| Blankets (not worn) | kamiskaglake | kįlaskaglake |

Note that the sense of "to wear" is most usually translated with patient-trigger voice - e.g. pāṇḍah jūnekah tę kamikyāyė "(s)he wears white robes" - while "to put on" with agent-trigger voice pāṇḍu jūneku kamitekyāyė "(s)he puts/is putting on white robes".

A few more specific verbs exist, like for example the pair kamilāṇṭake/kįlalāṇṭake, used for putting on/taking off a lāṇṭepenai (colloquially just penai), a kind of net made of Calemerian juta (lāriṭa) usually worn by adolescent girls (traditionally it was worn by unmarried women) with "cotton" hair (bhadvausiñe, or how Chlouvānem people call "Afro-textured hair").

Case agreement with participles and adverbials

Chlouvānem participles and adverbials are inflected for voice. For participles, the cases in the participial clause do not vary; the voice identifies which role the noun in the main clause has in the participial clause. The participial clause has thus the same marker as in a normal patient-trigger-voice clause. Some examples follow:

- lilei priemęlьcāh fluta - the bag which has been given back by the person

- fluta pritėmęlьcāh lila - the person who has given back the bag

- fluta dhurvāneiti prikevemęlьcāh lila - the person for whose benefit the bag has been given back to the police

- fluta ītulom prituremęlьcāh lila - the person for whose misfortune the bag has been given back to the thief

- håmarṣūvī nīpanutsusah fluta - the bag in which the keys lie

- fluta priūsyemęlьcāh lila - the person who has been given back the bag

- fluta demie maihei priūsyemęlьcāh lila - the person who has been given back the bag by his/her own daughter

- ītulas lāṇṭamñe lilei utuñjąmea fluta - the bag with which the thief has been hit on the head by the person

For adverbials, it's different. These rules obviously do not apply to heterofocal adverbials, as the trigger of the main clause does not have any role in the other; on the other hand, homofocal adverbials mark the cases as if the trigger were in the clause the adverbial refers to. Compare the first example here with the penultimate of the adjectives:

- flutu demie maihei priūsyemęllīse lila hånyadaikah moe. - the person, having been given back the bag by his/her own daughter, was happy.

- ālīce guṃslūte liliā pamih uyūṭarau rileyekte. - my finger, having been cut that way, needed an operation.

- panaʔetatimu læmilāṇe arūppumei ilaklīsetū læmьlila menire pifreṣṭasyiṣya. - the driver, being disadvantaged as (his/her) championship rival has taken pole position, will have to take some risks tomorrow.

Relative clauses and equivalents

Chlouvānem relative clauses are nonreduced and built in a correlative structure: both clauses are independent, with the relative clause defining the shared noun with a relative pronoun (the te- column of the table of correlatives) while the main clause uses the corresponding distal one (nanā (ateni in Archaic Chlouvānem) and variations).

The structure is thus as follows:

- tėvita jāyim sęi mešė nanā jāyim liliā buneya.

- which_person.REL.DIR. girl.DIR.SG. 2S.ERG. see-IND.PRES.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT. that.DIR. girl.DIR.SG. 1S.GEN. older_sister.DIR.SG.

- My older sister is the girl that you see.

It should be noted that, when relative clauses are about things or people (thus requiring the relativizers tejāmi or tėvita), this strategy is commonly only used for free relative clauses, while bound relative clauses are most commonly built by using verbal participles.

The example sentence “My older sister is the girl that you see” in normal speech is:

- sęi mekṣusam jāyim liliā buneya.

- 2S.ERG. see-PART.PRES.EXTERIOR.PATIENT-LOTUS.DIR. girl.DIR.SG. 1S.GEN. older_sister.DIR.SG.

In a free relative clause, the correlative structure is the most common one, with sentences such as:

- tejāmiau mešute nanāt gu tarliru ša.

- which_thing.REL-ACC. see-IND.PRES.1S.EXTERIOR-AGENT. that-EXESS. NEG- know-IND.PRES.1S.INTERIOR. -NEG.

- I don’t know/understand what I see.

With all other relativizers, the correlative structure is usually the only solution; place (tėjulā) and manner (tėlīce) may use participles in locative-trigger or instrumental-trigger instead, but still the correlative structure is preferred:

- liliā ñæltah tėmiya līlekhaitom tesmudhiṣya ātiya tami lairkeikom khlavasiṣyalį.

- 1S.GEN. sister.DIR.SG. when.REL. Līlekhaitė-DAT. depart_with_plane-IND.FUT.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT. then. 3S.DIR.PARROT. airport-DAT.SG. go_with.IND.FUT.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT-1S.ERG.

- When my sister takes the plane to Līlekhaitė, I will go with her to the airport.

- tami tėmena tū kulekte ātmena gu tarliru ša.

- 2S.DIR. why.REL. 3S.ACC. say-IND.AOR.3S.EXTERIOR-AGENT. that_reason. NEG- know-IND.PRES.1S.INTERIOR. -NEG.

- I don’t know why (s)he said it.

Conditional sentences

Conditional sentences in Chlouvānem grammar are those generally introduced by the particle pū, meaning "if". There are two general categories of conditional sentences: real and hypothetical.

Real sentences are those where the sentence expresses an implication that is always true. These sentences are generally in the indicative mood; note that in real, just like in hypothetical, sentences, mārim (then) is optionally used in order to introduce the second clause:

- pū nāmvite (mārim) tåh ryukaši. "if you hit him/her/it, you hurt him/her/it."

- pū yañšu udhyuʔeste tafluniṣya. "if you have called her [honorific], she will come."

Hypothetical sentences are those where the result may be or might have been true if the condition gets/would have been fulfilled. There are two main possibilities:

- Present conditions, where the condition either might be fulfilled or just can't at all. They are similar in structure to real sentences with present tense conditions, but, if the condition is fulfillable, they differ in the fact that the condition, is not likely to happen, or is used as a warning. The condition (pū-clause) is always in the imperfective subjunctive; the second clause may be in the indicative (carrying an implicate result) or in the subjunctive (implying a wish):

- lili mæn pū nanū nūlastān gīti samvaru kitu lgutevitaṃte. "if I had more of money, I'd buy (perf. aspect) a bigger house."

- lili mæn pū nanū nūlastān gīti chloucæm lilatiam. "if I had more money, I'd live (impf. aspect) better."

- pū nanū pāṭṭarudrīderi nanū tṛliriṣyari/tṛlirdia. "if you two study more, you two would know/understand more." Note that in such a sentence there's no difference between using a future (e.g. tṛliriṣyari here) or a present indicative (tṛlirdia here).

- pū liliā bunā gėrisa gīti tami liliā bunā gu gīti ša. "if my father were a lake, he wouldn't be my father."

- Unfulfillable past conditions, where the condition could have been fulfilled in the past but wasn't. The pū-clause is always in perfective subjunctive, while the other may be either imperfective or perfective depending on the meaning.

- mei tati pū kulevitaṃte yaiva gātarah gīti. "if I had said 'yes', everything would be different (now)."