Alska

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

| Alska | |

|---|---|

| Alska | |

| Pronunciation | ['alska] |

| Created by | Darthme |

| Setting | Scandinavia/The Baltic States |

| Native speakers | No Census Data (2013) |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia |

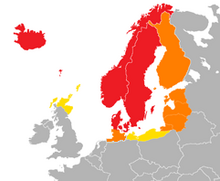

A map showing Alska's intended area of use. Red represents the countries which speak languages Alska was based on, Orange represent countries whose languages are not related to Alska, but which may interact frequently with Alska-speakers. Yellow areas are parts of countries that may encounter Alska speakers, but would not normally frequently interact with them. | |

Background

Alska ['alska] is a Western Scandinavian language created for the purposes of enhancing mutual intelligebility across the main scandinavian languages, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian. Icelandic and Faroese are represented in the orthography and three-gender system of the language as well as the use of the letter (ð), but most of the main vocabulary is made up of mainland Scandinavian words. It is designed to be mutually intelligible to all Scandinavians without borrowing too heavily from any one language.

Also, as a small note, primary stress will be marked in IPA with (') as usual, but secondary stress will be marked with (.) because it is annoying to insert the (ˌ) mark every other syllable.

Phonology

| Letter | Pronunciation | Further information |

|---|---|---|

| a | [a]/[ɑ] | |

| á | [aʊ] | corresponds to (av) as in Danish havnen |

| b | [b] | |

| d | [d] | |

| ð | [ð] | pronounced somewhere in between Icelandic (ð) and (d) in Danish (mad), (gade), (flåd) |

| e | [ɛ]/[e] | |

| é | [ei:] | Icelandic (ei), Swedish (ej) |

| f | [f] | |

| g | [g] | |

| h | [h] | |

| i | [ɪ]/[i:] | |

| í | [ai:] | corresponds with (ej)/(ei) in Danish/Norwegian, as well as certain instances of (eg) in Danish |

| j | [j] | |

| k | [k] | |

| l | [l] | |

| m | [m] | |

| n | [n] | |

| o | [ɔ]/[o] | |

| p | [p] | |

| r | [ɾ] | tapped in all positions |

| s | [s] | |

| t | [t] | |

| u | [u] | often realized as [ʉ] by many speakers |

| v | [v] | |

| y | [y:] | pronounced almost like German (ü) |

| ø | [ø] | may also represent [œ], but the distinction is not made in Alska |

| å | [o:] |

Consonants

| Phonemes | Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | p b | t d | k g | |||||

| Affricate | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ (ŋg) | |||||

| Fricative | f v | s | ɕ tɕ | (ç) | h | |||

| Approximant | ɾ | j | ||||||

| Lateral approximant | l |

- (sj)/(kj) represent [ɕ], but (kj) may also be realized as [ç] by some speakers.

- (tj) represents [tɕ]

- (ng) represents [ŋ], which occurs mostly as a word-final sound. Some speakers tend to realize (ng) as [ŋg] in its word final position, and [ŋ] elsewhere.

I.e: (betydning - meaning) [bɛ'ty:d.nɪŋg] - (betydningen - the meaning) [bɛ'ty:d.nɪŋ.en]

Vowels

| Phonemes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | |

| Closed | i y | u ʊ |

| Mid-closed | e ø | o |

| Mid-open | ɛ | ɔ |

| Open | a | ɑ |

Vowel Length

There is no reliable way to determine vowel length, however, if a vowel precedes a double consonant such as (tt), it is safe to assume it will be short. A notable exception is for certain adjectives which gain a double consonant from inflection. The vowels in these adjectives will retain the same quality as before the inflection. The vowels (å) and (ø) cannot change in length. Likewise, the letters (á), (é), and (í) cannot become short because they represent diphthongs.

Stress

Alska uses stress to differentiate words instead of a pitch accent like Norwegian and Swedish do.

Stress usually falls on the first syllable of a word. Words that do not follow this pattern are usually loanwords, which follow their original pronunciation rules when adopted, although the spelling is often changed to help integrate them into Alska.

The prefixes (for-), (be-), and (u-) are unstressed, and primary stress falls on the syllable after them.

- forstå [foɾ'sto:] - to understand

The endings (-tion), (-ti/tik), (-aner), and (-ør) are receive primary stress, even if there is another syllabe after them (for example, the plural ending)

- politikkar [pɔlɪ'tɪk.aɾ] - politicians

Grammar

Nouns

There are three grammatical genders in Alska: Masculine, Feminine, and Neuter. Each gender is distinguished by a different enclitic article when a noun is definite. Likewise, each gender has its own indefinite article. The three endings are (-en) for the Masculine, (-an) for the Feminine, and (-et) for the Neuter. Additionally, (-er/ar) is the most commonly used plural marker.

Definite vs. Indefinite

Whether a noun is definite or not is decided by the use of an enclitic article in the form of a suffix. These articles can be seperated from the noun and used in a sentence to transform them into indefinite articles.

For example:

| Singular | Indefinite Plural | Definite | Definite Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| feminine: | |||

| jinte | jintar | jintan | jintana |

| girl | girls | the girl | the girls |

| masculine: | |||

| dríng | drínger | dríngen | dríngerne |

| boy | boys | the boy | the boys |

| neuter: | |||

| hus | huse | huset | husene |

| house | houses | the house | the houses |

Articles

While definiteness can be determined by an enclitic article, demonstrative articles are also used, which show definiteness, but are not attached to their noun. All genders are represented, expect for in the plural, when the article (de) is always used regardless of gender.

| Gender | Demonstrative article | Indefinite Article |

|---|---|---|

| Masculine | den | en |

| Feminine | dan | an |

| Neuter | det | et |

| Plural | de |

There are no plural forms for indefinite articles, as the are only ever used to refer to singular things. (denne), (danne) (dette) are all used for this/that, these, or those; one only has to switch between them due to a noun's gender.

It should be mentioned that the distinction bewteen (den) and (dan) is not always clear. Most mainland Scandinavians tend to pronounce them almost the same since they are used to only distinguishing between two grammatical genders in their native languages. Even in some cases in Icelandic, the Masculine and Feminine are pronounced the same, and are only clearly seperate in writing as (-inn) and (-in).

With this in mind, both (den) and (dan) tend to be pronounced [dɛn]. Likewise, if an emphasis is being put on the word, it can be pronouned as [den]. This happens when the speaker is talking about a specific object, similar to the difference between saying the car and that car in English. This is also true for the indefinite forms (en)/(an)

Personal Pronouns

Personal pronouns change depending on the case they are used in. (Nominative, Accusative, or Genitive) Possessive Pronouns change depending on the gender of the noun they possess.

| Case | 1st person | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |||

| Nominative | jíg | vi | ||

| Accusative | míg | oss | ||

| Genitive | min / mina / mit / mine | vår /våre | ||

| Case | 2nd person | |||

| Singular | Plural | |||

| Nominative | du | i | ||

| Accusative | díg | ig | ||

| Genitive | din / dina / dit / dine | iger / ige | ||

| Case | 3rd person | |||

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural | |

| Nominative | han | hun | det | de |

| Accusative | ham | hun | det | de |

| Genitive | hans | hinnes | dettes | deres |

The possessive pronouns (min) and (din) change based on gender, but their plural versions, (iger) and (vår) do not distinguish gender, only plurality.

Also, it is important to remember that (han) changes to (ham) in the Accusative, but back to (hans) in Genitive.

There is no true Gentitive case in Alska, only possessive pronouns. There is no Dative case at all.

Adjectives

Adjectives in Alska are inflected for gender and number, in the same mode as nouns are made definite with (-e), (-a) and (-t). The plural ending is always (-e), adjectives do not inflect for gender in the plural. If a noun is masculine or feminine, and is indefinite, the adjective does not have to be inflected. If the noun is neuter, a (-t) must be added even if the noun is indefinite. If the noun is indefinite and plural, the noun must be inflected.

Here are some examples:

| Singular | Indefinite Plural | Definite | Definite Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| feminine: | |||

| an smuk jinte | smukke jintar | dan smukka jinte | smukke jintana / de smukke jintar |

| a pretty girl | pretty girls | the pretty girl | the pretty girls |

| masculine: | |||

| en vak dríng | vakke drínger | den vakke dríng | vakke dríngerne / de vakke drínger |

| a handsome boy | handsome boys | the handsome boy | the handsome boys |

| neuter: | |||

| et gult hus | gule huse | det gult hus | gule husene / de gule huse |

| a yellow house | yellow houses | the yellow house | the yellow houses |

It is important to notice that some adjectives gain a double consonant when they are in their definite forms: (vak - vakke)/(smuk - smukke). This would not happen if these adjectives were inflected for neuter gender: (smuk - smukt)/(vak - vakt). Other adjectives do not gain a double consonant, such as (gul). This does not change the pronunciation of the vowel proceeding the double consonant, although many times double consonants indicate a short vowel before them.

Comparative

The comparative form of adjectives is formed by adding (-er)/(-ara) to the adjective. The word 'enn' precedes the noun being compared. The adjective is inflected for the gender of the first noun being compared. One may also use the construction X er mer ___ enn Y. In this case, the adjective does not inflect for gender.

For example:

- den man er stérker enn danne jinte - the man is stronger than that girl.

- danne jinte er mer stérk enn denne man. - that girl is stronger than that man.

If something is being compared on the same level, (så) is used before the adjective, and (som) is used after. Additionally, the adjective is not inflected, as the two nouns being compared are of equal status. It is also acceptable to say X er ____ som Y. Once again, in this construction, the adjective does not inflect, although this implies a slight difference: using this construction means that X has an attribute like Y, but does not necessarily imply that the two are on the same level exactly.

- danne jinte er så stérk som danne jinte - that girl is (just) as strong as that girl.

- det hus er pént som det hus (derover) - the house is pretty like that house (over there).

If something is being compared as less than another noun, (mintre)/(mintra) is used before the adjective, and (som) is used after. The adjective is inflected normally for the gender of the first noun. (This can also be acheived by saying X er ikke så ____ som Y)

- det hus er mintre smukt enn dette hus - the house is less beautiful than that house.

- den man er ikke så store som denne man - the man is not so large as that man.

Irregular Adjectives

Irregular adjectives are normal until they reach the comparative stage. Instead of adding the suffix 'ere', these irregular adjectives are usually put into the comparative by changing the entire word (compare to English 'good', 'better', 'best')

Here is an example of an irregular adjective being used comparatively.

- det hus er godt - the house is good

- det hus er bettre - the house is better

- det hus er (det) beste - the house is (the) best

- dette hus er bettre en det hus - this house is better than that house

Superlative

The superlative form of an adjective is used when saying something is the 'best'. For regular adjectives, the superlative ending is '-est'. Irregular verbs usually end in '-est', but it is part of the stem, or root. In other words, the adjective changes twice, once for comparative, again for superlative, and the superlative version ends in '-est'.

Here is a table showing regular and irregular adjectives in their three forms:

| Regular Adjective | Comparative | Superlative | Meaning | Irregular Adjective | Comparative | Superlative | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stérk | stérkere | stérkest | strong | god | bettre | beste | good |

| lang | langere | langest | long, tall | makket | mere | mest | much |

| ung | ungere | ungest | young | gamell | eltre | eltest | old |

| kold | koldere | koldest | cold | lille | småler | smålest | little, small |

- (smål) by itself is the plural version of (lille)

Numbers

| Number | Cardinal | Ordinal |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | null | |

| 1 | en | vørste |

| 2 | to | annen |

| 3 | tre | trede |

| 4 | fjir | fjerde |

| 5 | fimm | fimmte |

| 6 | sex | sjett |

| 7 | syv | syvente |

| 8 | åtte | åttente |

| 9 | ni | niente |

| 10 | ti | tiente |

| 11 | ellfu | ellfte |

| 12 | tolfu | tolfte |

| 13 | treten | tretante |

| 14 | fjirten | fjyrtente |

| 15 | fimmten | fimmtente |

| 16 | sejksten | sejkstente |

| 17 | sytten | syttente |

| 18 | atten | attente |

| 19 | nitten | nittente |

| 20 | tjyve | tjyvente |

| 21 | tjyveen | tjyveente |

| 22 | tjyveto | tjyvetoente |

| 30 | treti | tretiente |

| 31 | tretien | tretiente |

| 40 | fjyrti | fjyrtiente |

| 50 | fimmti | fimmtiente |

| 60 | sexti | sextiente |

| 70 | syvti | syvtiente |

| 80 | jåtti | jåttiente |

| 90 | niti | nitiente |

| 100 | hundre | hundrete |

Forming numbers higher than 19 works on the same principles as English, except the hyphen is not used to seperate the numbers: (Tjyve) and (En) combined make (Tjyveen) - (Twenty-one). Numbers with hundreds and thousands work the same way.

Ordinal numbers are formed by suffixing either (-ente) or (-te) to the number in question, except for the numbers 1 to 4, which are irregular in their ordinal versions.

Interrogatives

| Interrogatives | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Alska | |||||||||

| who | vem | |||||||||

| what | vad | |||||||||

| where | vor | |||||||||

| why | vorfor | |||||||||

| how | vorden | |||||||||

| when | vornår | |||||||||

| which | vilke / vilka / vilket | |||||||||

- vornår is the interrogative version of når, which is used for other time-statements.

Adverbs

Adverbs are not distinguished from adjectives, and are not inflected. They can be placed before or after a verb, although they are generally placed after.

Examples:

- han kan løpe - he can run

- han kan løpe hurtig - he can run quickly (lit. he runs fast)

- han løper god - he runs well (lit. he runs good)

- han kan god løbe - he is up for running / he would like to run (right now)

When using the adjective (god) as an adverb, it is important to recognize the difference between placing (god) before or after the verb. When placed after the verb, it indicates that the subject does the verb well. However, when placed before the verb, it changes the meaning of the entire sentence. (god) now indicates that the subject would like to perform the verb, or is receptive to the idea of doing the verb's action. See the last example above for clarification.

(god) may still be used before the verb, but it must be used in a different construction where the main verb becomes a sort of infinitive gerund and (er) becomes the main verb in the sentence. This form is often used in the vernacular over example 3 above:

- han er god til at løpe - he is good at running (lit. he is good at to run)

Verbs

Verbs in the infinitive form are accompanied by 'ett', and 'e' on the end. For example: Kyk - Cook, ett Kyke - to cook. There are almost no irregular verbs, and conjugation of most verbs is done by adding the suffix '-r' to the infinitive.

'-r' is used for all pronouns

- Jeg kyker i dag - I cook today/I'm cooking today

- Du kyker i dag - You cook today/You're cooking today

Er is used only in the context of 'to be', not as an auxiliary verb, as in English 'I am writing'. In Alska this would be Jeg skriver, NOT Jeg er ett skrive.

Verbs appear in their full infinitive form in a sentence when another primary verb is being used, often preceded by for, but not always. The verb+e version of the infinitive can appear after a modal verb.

Here is an example of all three forms:

- Jeg skriver - I write

- Jeg vil skrive - I want to write

- Jeg skriver over for ett kyke - I write about cooking

Past Tense

Past tense of verbs is usually done through suffixing, although a small portion of them go through stem vowel changes.

The suffixes for most words are '-dde', or '-te'.

| Verb | Present | Past | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| ett Skrive | skriver | skrivte | to write |

| ett Kyke | kyker | kykte | to cook |

| ett Lufe | lufer | lufte | to run |

| ett Finne | finner | finnedde | to find |

| ett Spise | spiser | spisedde | to eat |

| ett Gå | går | gir | to go |

Irregular Past Tense

There is a very short list of verbs that undergo a stem-vowel change for their past tense form, although there is order to this and if one learns what each vowel changes to, they must simply remember the specific word it occurs in.

| Vowel | Changes To |

|---|---|

| a | e |

| e | a |

| i | u |

| o/å/ø | i |

| u | o |

Here is a table showing the stem vowel changes for certain verbs:

| Verb | Present | Past Tense | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| ett Gå | går | gir (gikk in some dialects) | to go |

| ett Vere | er | var | to be |

| ett Hive | hiver | huver | to heave, lift |

Note how the '-r' is not changed, even when the verb is in the past tense.

Forming Commands

Forming commands in Alska is quite simple. When one wants to form a command, such as 'give me that', they need only to move the verb to the beginning of the sentence. The verb being used as a command stays in its present tense conjugation, and will always stay in that form no matter what tense the rest of the sentence is in.

This rule applies in English, also: One might say, 'give me that' in the present tense, but later say, 'I told him to give me it.' Notice how the commanding verb is the same, even though the speaker of the sentence is referring to the actual command in the past tense.

Additionally, when referring to one's self in a command statement, the accusative form of the personal pronouns must be used.

Here are some examples:

- Giver mig det - Give me that (Jeg - Mig)

- Holder dette - Hold this

- Hjelper mig hiver den! - Help me lift this!

Notice how in all of these statements, the second person is never acknowledged (du). It is understood that you are telling another person to perform an action, so no form of du needs to be used in the sentence. However, if you were to use the verb ett Måe - (Must) in the statement, du would have to be used:

- Snaker med han - Speak with him

- Du må snaker med han - You must speak with him

Past Participle

The past participle form of a verb always comes with the verb ha - to have. Ha is always conjugated in the present tense, but the verb main verb is always in the past tense. Past participle forms retain the same suffixes they had in their regular past tense form.

For example:

- Jeg har gir till Alsland - I have gone to Alsland (before)

The main verb, or the verb in the past tense, does not have to be in any specific place in the sentence as long as it is after ha; It is just as acceptable to say Jeg har till Alsland gir

Syntax

Syntax in Alska has a rather straightfoward SVO pattern, like most Germanic langauages. Also like most Germanic languages is the switch to VSO for interrogative statements.

- Jeg vil lufe - I want to run

- Vil jeg lufe? - (Do) I want to run?

Notice how there is no auxiliary verb in the second example. Translated literally, it means 'Want I run?'.

Cases

Alska has 4 grammatical cases: Nominative, Accusative, Dative, and Genitive.

Nominative

Nominative Case is used to show the subject of a sentence, although there is no case marking for this case in Alska.

Accusative

Accusative Case shows the direct object of a sentence, and once again there are no case markings for it.

While there is no direct marking on the noun, pronouns do change to conform to Accusative case.

- jeg - mig

- du - dig

Dative

Dative Case shows the indirect object of a sentence, and is the one case where case marking occurs. The indefinite and definite articles undergo a vowel shift, from 'e' to 'a'.

- en/et - an/at

- *den/det - dan/dat

Genitive

Genitive Case shows possession of a noun by another entity, and is the only case that has in-depth rules.

Possession can be shown in two ways: with a possessive pronoun or in an 'of the' phrase. Using a possessive pronoun is more common in speech, although there are situations where an 'of the' phrase would be more accurate.

When showing possession with a pronoun, one simply puts the pronoun in front of the noun being possessed. For example:

- minn skole - my school

- ditt hus - your hus

Notice how the syntax here is exactly like English. This is by far the easiest way to use Genitive case. Also notice how 'dinn' changes to 'ditt'. This is because 'hus' is neuter in gender. This change applies to most possessive pronouns when they own a neuter word.

There is no actual 'of the' phrase in Alska, instead the noun being possessed is made definite and put in front of a possessive pronoun:

- skolen minn - the school (of) me

- huset hans - the house (of) his/his house

'Hans' and 'huns' are the only two pronouns that do not undergo the 'tt' change when possessing a neuter noun. They are also used instead of 'sinn

'Sinn' is used for the first kind of possession, and hans/huns is used for the second.

When a proper noun is possessing something, the suffixes '-s', or '-es' are used. '-s' is suffixed onto proper nouns, such as names and places, and '-es' is suffixed onto regular nouns. If the noun is definite, the genitive suffix comes after the enclitic article. This happens in both types of possession:

- Alslands fylger/Flygene alslands - Alslands women/the women of Alsland

- Kattenes ball/Ballet kattenes - The cat's ball/The ball of the cat

Ja and Ju

In Alska there are two affirmative words: Ja, which is used for regular yes/no answers, and Ju, which is used for negative questions.

Negative Questions are formed when ikke is used. Observe the difference between these two questions:

- Vil du lufer med mig? - Do you want to run with me?

- Vil du ikke lufer med mig? - Don't you want to run with me?

The answer to the first question would be Ja, while Ju would have to be used in the second question if the person does in fact want to go running.

This helps with the confusion that occurs with negative questions. For example, in English, the question 'don't you want to run with me?' is not seen as an inherently negative statement, but when one separates 'don't', the statement's implied meaning changes. Now it becomes 'do you not want to run with me?'. Answering yes to this question would mean that you do not want to run. However, if you do want to run, you would have to clarify the statement: 'Yes, I do want to run with you.'

The use of Ju eliminates the need for this confusion.

Examples

Here is the Lord's prayer translated from English into Alska:

| English | Alska |

|---|---|

| Our Father in heaven, | Vår Féðer i himmell, |

| hallowed be your name. | helige er din Nán. |

| Your kingdom come, | din kongdøm kommer, |

| your will be done, | din will skal gøres, |

| on earth as it is in heaven. | på jorden som det er i himmell. |

| Give us this day our daily bread, | giv oss vår daglig brød, |

| and forgive us our debts, | og tillgiv oss våre skulder, |

| as we also have forgiven our debtors. | ligesom vi har tilgiveðe våre skuldmen. |

| And lead us not into temptation, | og led oss ikke i på frissthellse, |

| but deliver us from evil. | men fremlév oss fra onda. |

Notes:

- while (féðer) is the 'proper' word for (father), it is usually replaced by (far) in common speech.

- (nán) is pronounced exactly the sae as Danish (navn), but may be confusing to some because of its drastically changed orthography)

- (will) is the noun version of (vil) - (to want, will), and borrows it's orthography from English to prevent confusion.

Here is a table which compares words in Alska to their Scandinavian equivalents as well as German, and shows their English meaning:

| Alska | Danish | Norwegian | Swedish | Icelandic | German | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| man | mand | mann | man | maður | Mann | man |

| fot | fod | fot | fot | fót | fuß | foot |

| land | land | land | land | land | Land | land, country |

| himmell | himmel | himmel | himmel | himinn | Himmel | sky, heaven |

| sku | sko | sko | sko | skór | Schuh | shoe |

| ljys | lys | lys | ljus | ljós | Licht | light |

| live | liv | liv | liv | líf | Leben | life |

| tir | dyr | dyr | djur | dýr | Tier | animal |