Attian

This article is a featured language. It was voted featured thanks to its level of quality, plausibility and usage capabilities.

Etu ethnema ta etu anzan uʾummen. Maye ta goyotita, ta ethahama, veta vemaguma, uʾunme mumnayyir. |

The creator of this language has moved on from this language. No further editing, other than marginal corrections, will occur in the foreseeable future. Watch out for inconsistencies and enjoy the page. |

| Attian | |

|---|---|

| Athnai | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [aθ'nai̩] |

| Created by | Waahlis |

| Native to | Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia |

| Native speakers | 61,000 (2012) |

Attamian

| |

Early form | |

Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | Academia ta Athnai |

| Language codes | |

| CLCR | qat |

Map picturing the Agartha region in Transcaucasia, crossing the borders of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. | |

Attian (Attian Hevriti: אתנְי, Latin: Athnai, /aθ'nai̩/) is a constructed, a priori and naturalistic language in the Attamian family of languages, descended from the hypothetical Proto-Attamian language. It has no other purpose than to be an excellent display of my personal debauchery and pleasures.

The language is being created by the user and administrator Waahlis of Linguifex. Obviously, and almost self-evidently, it has no native speakers and is not the official language anywhere else than in an office.

Background

Naturalism nowadays implies the creation of fictional settings, to legitimate the choice of vocabulary, semantics and pragmatics. I will for once actually do such a thing, implementing the language into the modern world of Caucasus. Perhaps then I can justify a few loan words.

Attian (Attian Hevriti: אתנְי, Latin: Athnai, /aθˈnai̩/) is an Attamian language spoken in the Caucasus, across the borders of Georgia, Armenia and Turkey. It is not known to have any transparent genetic connections to any other language, despite a number of attempts of classification.

The language has been documented in the Caucasus since at least the 9th century AD, with the discovery of the Hayastani documents, (Attian: Egrava ta Hayaztan, חגרְוְ טְ חְיְזטְן) a Greek transcript of the languages in an around the Transcaucasian settlements. The now fragile documents were written by the Byzantine Greek philosopher Antenor Erevanon, in an effort to investigate the ethnic diversity i the region:

The number of speakers of the language is unknown, but the numbers are estimated to be fairly low. Influence by neighboring languages, such as Armenian, Georgian and enclaves of Greek, Hebrew and Qafesona speakers threaten the language by the inclusion of loanwords, but the greatest threat is from the universal English language, as more and more Attians acquire internet and television, featuring the language.

Phonology

- For more information, go to Attian/Phonology

This is the complete consonant and vowel phoneme inventories of the Attian language, they are the sounds with minimal pairing effect on lexemes. The language is notable for missing one of the conventional plosive series among consonants, missing a phonemic distinction of the complete bilabial place of articulation. It also differentiates four pairs of rounded and unrounded vowels.

Please note that the bolded letters are orthographic representations.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Consonants

The Attian consonants undergo a number of phonological processes, all of which are completely phonemic.

Voicing

The phonemes /s/, /ç/, /k/, /r̥/ and /h/ are all voiced when following a voiced consonant, preceeding /w/, or when in intervocalic position.

Labiovelar coarticulation

The labiovelar coarticulation, or simply labiovelarisation, is a process which only applies to the velar stops, that is /ŋ/, and /ɡ/. The velar stops are coarticulated with their labial analogue when followed by a rounded vowel. This causes the phonemes /ŋ͡m/, /k͡p/ and /ɡ͡b/.

Other situations producing the labiovelars, and especially the nasal one, are collisions of /ŋ/ and /n/, no matter the order. In addition, the combinations /n/ or /ŋ/ + /w/ grants the labiovelar nasal /ŋ͡m/.

| ugga | amnva | gva ugga giga | ||

| /uɡˈɡø/ → /uˈɡ͡bø/ | /aŋˈna/ → /aˈŋ͡ma/ | /ɡwa uɡˈɡø ˈɡiɡø/ → [ɡwa uˈɡ͡bø ˈkiɡ͡bø] | ||

| fish | you; thou | I fish fish |

Aspiration

The two plosives /t/ and /d/ are aspirated into /tʰ/ and /dʰ/ intervocalic positions.

| Part of a series on the |

| Attian language |

|---|

|

| Main |

|

Attian |

| Vocabulary |

|

Derivations |

| Contionary |

|

Verbs |

| IPA |

|

IPA for Attian |

Aspiration only applies should the plosives occur as a coda, or onset in an unstressed syllable. This implies that any aspiration due to external sandhi, i.e. if the preceeding word ends with a vowel, is impossible.

| adina | yetai | |

| /aˈdina/ → [aˈðina] | /ˈjɛtai̩/ → [ˈjɛtʰai̩] | |

| meal | small eye; peeking Tom |

Other

The glottal fricative /h/, has an irregular effect if preceding or following hetero-organic plosives. The hetero-organic plosive is geminated, or doubled, and the glottal fricative is deleted from speech.

Vowels

This is the vocalic phoneme inventory of the Attian language. All of the following phonemes are phonemic, however, due to severe allophony in most dialects, the inventory is somewhat larger. The Attian language has 10 basic vowels, whereof four rounded and six unrounded.

| Front | Near- front | Central | Near- back | Back | ||

| Close |

| |||||

| Near-close | ||||||

| Close-mid | ||||||

| Mid | ||||||

| Open-mid | ||||||

| Near-open | ||||||

| Open | ||||||

Vowel reduction

There is a slight reduction of /u/ and /ɛ/ in open coda to /ʊ/ and /ə/ respectively.

Diphthongs

There is an amount of phonemic diphthongs in the Attian language. They non-syllabic elements [i̯] and [u̯] are heavily allophonic with /j/ and /w/ respectively, and most often simplified as such.

| Rising | Falling | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ya | [ja] | ay | [aj] | ||||

| ye | [jɛ] | ey | [ɛj] | ||||

| yi | [ji] | iy | [ij] | ||||

| yo | [jo] | oy | [oj] | ||||

| yu | [ju] | uy | [uj] | ||||

| va | [wa] | av | [aw] | ||||

| ev | [wɛ] | ev | [ɛw] | ||||

| vi | [wi] | iv | [iw] | ||||

| vo | [wo] | ov | [ow] | ||||

| vu | [wu] | uv | [uw] | ||||

Vowel allophony

- For more information, go to Attian/Phonology

Dialectal or colloquial variances in the Attian language includes vowel allophony. When subjects to stress, vowels may change their quality:

- Preceding palato-velar or glottal consonants. This retracts articulation of front vowels, and leaves back vowels unaffected.

- Preceding rhotic consonants, i.e. /r̥/. Vowels preceding the rhotic become supradentalised if back, and unaffected if front vowels.

- In a stressed syllable. The language has a moraic stress system, thus distinguishing the weight of syllables - the heavier the syllable, the greater chance of being stressed.

Phonotactics

C = Consonant

N = Nasal stop

V = Vowel or Diphthong

The Attian language's phonotactics, are quite restricted. The syllable structure is different whether in initial or medial position, and it has a great impact on the lexical stress.

Initial syllables does not require an onset of any kind, but does require a coda consisting of at least one consonant. Medial or final syllables, dubbed General, may however only have codae consisting of one consonant and one nasal, or two successive nasal stops.

Attian possesses a moraic stress system which similarly to Latin follows a dreimorengesetz, three-morae-rule, which in this case dictates that the third mora is always stressed. Since onsets are moraic in Attian, the initial syllable accounts for three morae quite often. Thus, the stress is always on the first or second syllable.

| Initial Syllable Structure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (C) | (C) | V | C | (C) |

| General | ||||

| (C) | V | (C)/(N) | (N) | |

This construction gives a language quite restricted in the number of onsets possible, in comparison to for example English phonotactics and phonology. In addition to this, only some of the possible clusters are actually present as onsets in the language. One should remember however, that all diphthongs belong to the vowel category. They increase the weight, but can still be in both coda and nucleus.

The coda consonant may be any consonant but ⟨j⟩ - final ⟨j⟩ simply does not occur. All roots inherited from Proto-Attamian lost the ⟨j⟩ in coda position.

Since the language is a rather fusional one, speakers should be wary of agglutinating morphemes. Should an affix be agglutinated to a stem, the affix normally loses its epenthic vowel. This occurs if a diaresis arises, or if the affix' consonant(s) is in compliance with the phonotactics.

Combinatorics

| This section is of the Attian article is in need of improvement of content, orthography or perspective. It will be done soon. |

Syllable codas

These are the syllables allowed in coda position in both syllable and lexeme.

| Codas | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finals | Codas | |||||||||||

| (none) | n | ŋ | t | d | k | g | s | ɹ | y | w | ||

| Monophthong nuclei |

a | a | an | aŋ | at | ad | ak | ag | as | aɹ | aj | aw |

| ɛ | ɛ | ɛn | ɛŋ | ɛt | ɛd | ɛk | ɛg | ɛs | ɛɹ | ɛy | ɛw | |

| e | e | en | eŋ | et | ed | ek | eg | es | eɹ | ey | ew | |

| ə | ə | ən | əŋ | ət | əd | ək | əg | əs | əɹ | əy | əw | |

| i | i | in | iŋ | it | id | ik | ig | is | iɹ | ij | iw | |

| ɤ | ɤ | ɤn | ɤŋ | ɤt | ɤd | ɤk | ɤg | ɤs | ɤɹ | ɤy | ɤw | |

| u | u | un | uŋ | ut | ud | uk | ug | us | uɹ | uy | ||

| ø | ø | øn | øŋ | øt | ød | øk | øg | øs | øɹ | øy | øw | |

| œ | œ | œn | œŋ | œt | œd | œk | œg | œs | œɹ | œy | œw | |

| o | o | on | oŋ | ot | od | ok | og | os | oɹ | oy | ow | |

| Diphthong nuclei |

aj | aj | ajn | ajŋ | ajt | ajd | ajk | ajg | ajs | ajɹ | aj | |

| ɛj | ɛj | ɛjn | ɛjŋ | ɛjt | ɛjd | ɛjk | ɛjg | ɛjs | ɛjɹ | ɛj | ||

| ej | ej | ejn | ejŋ | ejt | ejd | ejk | ejg | ejs | ejɹ | ej | ||

| əj | əj | əjn | əjŋ | əjt | əjd | əjk | əjg | əjs | əjɹ | əj | ||

| ij | ij | ijn | ijŋ | ijt | ijd | ijk | ijg | ijs | ijɹ | ij | ||

| ɤj | ɤj | ɤjn | ɤjŋ | ɤjt | ɤjd | ɤjk | ɤjg | ɤjs | ɤjɹ | ɤj | ||

| uj | uj | ujn | ujŋ | ujt | ujd | ujk | ujg | ujs | ujɹ | uj | ||

| øj | øj | øjn | øjŋ | øjt | øjd | øjk | øjg | øjs | øjɹ | øj | ||

| œj | œj | œjn | œjŋ | œjt | œjd | œjk | œjg | œjs | œjɹ | œj | ||

| oj | oj | ojn | ojŋ | ojt | ojd | ojk | ojg | ojs | ojɹ | oj | ||

| aw | aw | aŋ͡m | aŋ͡m | awt | awd | awk | awg | awɹ | aw | |||

| ɛw | ɛw | ɛŋ͡m | ɛŋ͡m | ɛwt | ɛwd | ɛwk | ɛwg | ɛwɹ | ɛw | |||

| ew | ew | eŋ͡m | eŋ͡m | ewt | ewd | ewk | ewg | ewɹ | ew | |||

| əw | əw | əwn | əŋ͡m | əwt | əwd | əwk | əwg | əwɹ | əw | |||

| iw | iw | iŋ͡m | iŋ͡m | iwt | iwd | iwk | iwɹ | iw | ||||

| ow | ow | oŋ͡m | oŋ͡m | owt | owd | owk | owg | owɹ | ow | |||

| uw | uw | uŋ͡m | uŋ͡m | uwt | uwd | uwk | uwg | |||||

| øw | øw | øŋ͡m | øŋ͡m | øwt | øwd | øwk | øwg | øwɹ | øw | |||

| œw | œw | œŋ͡m | œŋ͡m | œwt | œwd | œwk | œwg | œwɹ | œw | |||

| ow | ow | oŋ͡m | oŋ͡m | owt | owd | owk | owg | owɹ | ow | |||

Consonant clusters

These are the consonant clusters allowed in syllable boundaries, and the results of non-allowed combinations.

| Consonant clusters | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finals | Primary | |||||||||||||

| n | ŋ | t | d | k | g | θ | s | x | h | ɹ | j | w | ||

| Secondary | n | nː | ŋ͡m | nt | nd | ŋk | ŋg | nθ | ns | ŋx | nː | nɹ | nj | ŋ͡m |

| ŋ | ŋ͡m | ŋː | nt | nd | ŋk | ŋg | nθ | ns | ŋx | ŋː | ŋɹ | ŋj | ŋ͡m | |

| t | tː | tː | θk | θk | tθ | ts | kx | tː | tɹ | tj | tw | |||

| d | ðg | ðg | dː | dː | dð | dz | dɣ | dː | dɹ | dj | dw | |||

| k | kn | kŋ | xt | xt | kː | kː | ks | kx | kː | kɹ | kj | kw | ||

| g | gn | gŋ | ɣd | ɣd | gː | gː | gz | gɣ | gː | gɹ | gj | gw | ||

| θ | θn | θŋ | θː | θs | θː | θɹ | θj | θw | ||||||

| s | st | st | sk | sk | sθ | sː | sx | sː | sɹ | sj | sw | |||

| x | xt | xt | xs | xː | xː | xr | xj | xw | ||||||

| h | nː | ŋː | tː | dː | kː | gː | θː | sː | xː | hː | ɹː | jː | wː | |

| ɹ | ɹn | ɹŋ | ɹt | ɹd | ɹk | ɹg | ɹθ | ɹs | ɹː | ɹː | ɹj | ɹw | ||

| j | jn | jŋ | jt | jd | jk | jg | jθ | js | jx | jː | jɹ | jː | jw | |

| w | ŋ͡m | ŋ͡m | wt | wd | wk | wg | wθ | ws | wx | wː | wɹ | wj | wː | |

Vowel clusters

The Attian language allows 12 phonemic diphthongs. Any other clusters of vocalic phonemes form diaereses. Inserting an epenthic glottal stop between these vowels is a common occurrence, or in some dialects, the glottal fricative /h/.

Exceptions to this are the allophonic diphthongs [e̯a], [oʊ̯], [ɛi̯] and [a̯ɑː], which arises as a consequence of stressed monophthongs. For more information, see the following section on stress.

Suprasegmentals

Stress

Attian's system of lexical stress is different to that of for example English. Unlike English, Attian possesses a moraic stress system which similarly to Latin follows a dreimorengesetz, three-morae-rule, which in this case dictates that the third mora is always stressed.

The Attian phonotactics establish the following syllable structure:

| Initial Syllable Structure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (C) | (C) | V | C | (C) |

| General | ||||

| (C) | V | (C)/(N) | (N) | |

Attian morae

The weight of an Attian syllable is determined out of three circumstances, each of which represent one mora. As it happens, the morae correspond to the three universal syllable segments:

- A syllable onset. (ω)

- An onset is built up by consonants before the nucleus. The weight is not affected by the number of consonants.

- A nucleus. (ν)

- The nucleus is mandatory and always composed of a diphthong or a vowel.

- A syllable coda. (κ)

- A coda is composed of the consonants after the nucleus. The weight is not affected by the number of consonants.

The conclusions are:

- A syllable may be realised at the most as (ω + ν + κ). Each of these represent one mora, three altogether.

- The phonotactics say that an initial syllable is realised minimally as VC, thus always receiving a syllable coda, (ν + κ), giving two morae altogether.

- The minimal syllable possible is the sole nucleus, (ν), and it only occurs finally.

This leaves four possible combinations:

- (ω + ν + κ)

- (ω + ν)

- (ν + κ)

- (ν)

Compare the following:

| Word | zema | atna | ethnema | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈzɛŋ͡m.ø/ | /at.ˈna/ | /ɛθ.ˈnɛŋ͡m.ø | ||||||

| Syllables | zem | a | at | na | eth | nem | a | ||

| Segments | (ω + ν + κ) | (ν) | (ν + κ) | (ω + ν) | (ν + κ) | (ω + ν + κ) | (ν) | ||

| Morae | 1 + 1 + 1 | + 1 | 1 + 1 | + 1 + 1 | 1 + 1 | + 1 + 1 +1 | + 1 | ||

| Translation | house | dog | language | ||||||

Due to the restrictions in the phonotactics, a word may only be stressed on the first or second syllable, depending on where the third mora lies. The first syllable always totals at least two morae, and the second at least one.

This makes it possible to formulate a law to describe the Attian stress pattern:

- If a word starts with a consonant, the first syllable is stressed. Should the word start with a vowel, the second syllable is stressed.

Notes

This also grants that stress is not phonemic, as it does not differentiate any minimal pairs. Nor is it lexic, but the stress changes should any affixes be attached to the word. There are however a few words that do not follow the basic stress patterns - a few loan words. Examples:

- gorizi - /kor.ˈiz.i/ not /ˈkor.iz.i/

- girl - from Greek "κορίτσι".

- gentagona - /k͡pœn.ˈtag.on.a/ not /ˈk͡pœn.tag.on.a/

- pentagons - from Greek "πεντάγωνα".

Effect on vowels

- For more information, go to Attian/Phonology.

The Attian stress affects and reinforces the vowel phonemes' articulation. Should the syllable nucleus consist of a diphthong, it remains unaffected.

Prosody

Morphology

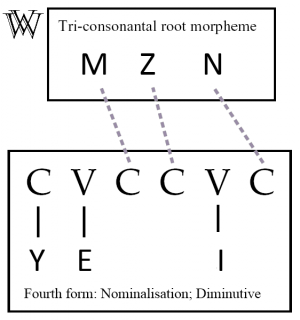

Radicals

The Attian language has an uncommon nonconcatenative morphology, where roots, or radicals, are inserted in a verb template. A root consists of a set of bare [w:consonant|]]s (usually two), which are fitted into a discontinuous pattern to form words.

The radicals of the Attian lexicon and the corresponding paradigms are used to form verbal and nominal inflection, derivation and miscellaneous grammatical functions, similarly to Arabic, Hebrew and other Semitic languages.

These roots, or radicals, have an inherent meaning, which may be altered slightly depending on the vowels inserted between the bare consonants. Here are a few examples:

- m-n - concerns vision.

- θ-n - relating to speech.

- g-ʾ - associated with horizontal movement.

The vowels or morphemes, called transfixes, are used in the formation of actual words from the abstract consonantal roots, or radicals. A large majority of these consonantal roots are biliterals, consisting of two radical consonants (although there are a number of uniliterals, and an amount of triliterals).

The Attian language distinguishes four different kinds of radicals:

- Uniliterals - Uniliterals consist of one, single consonant and are very uncommon. They only appear as particles or articles.

- Biliterals - Biliterals are composed of two consonants, and is the biggest group of radicals. It is divided into two types:

- Single biliterals - Single biliterals are the most common radicals in the Attian language. They consist of two bare consonants.

- Double biliterals - The double biliterals are derived from single biliterals. The two radicals are compressed into a consonant cluster, and a third radical is added.

- Triliterals - Triliterals are few, but also consist of derivations of biliterals. They have three bare consonants.

Vowel patterns

The Attian patterns of transfixes, "vowel patterns", are plentiful and most often rather irregular. The patterns are diverse for nouns, but the verbs have more standardised forms; see the section on verbal inflexion.

Some forms do not exist in combination with certain radicals - should the semantics or phonotactics forbid. At times, the meaning of some vowel patterns may coincide and create synonyms. One example is ethnema, thenma and thina, all meaning "language".

| Approximation of common transfixation patterns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | ||

| Alienable | C₁aC₂a | eC₁iC₂a | C₁iC₂a | C₁aC₂a |

| Inalienable | C₁eC₂i | eC₁C₂i | C₁aC₂i | uC₁C₂a |

| Abstract | aC₁iC₂a | eC₁iC₂a | C₁iC₂a | C₁eC₂a |

| Concrete | aC₁C₂a | eC₁iC₂a | C₁aC₂u | aC₁C₂u |

Above is a table of gender contrasting with characteristics. It displays a few of the vowel patterns, at least those that are predictable in form and meaning. Below are a few applications of the patterns on a few roots.

| √th-n + CaCu | √g-m + CeCa | √g-n + eCiCa | ||

| thagu | gema | egina | ||

| Related to speech | Related to arrival | Related to knowledge | ||

| mouth | arrival | wit |

Since the Attian language utilises transfixes, the glossing is made with a slash ⟨ / ⟩ following the translated word, and the glossing thereafter.

Nouns

The language inflects according to four different cases, patientive (pat), agentive (agt), instrumental (ins) and locative (loc) through radical patterns. In addition, there are three different numbers, collective (col), singular (sg) and plural (pl), where the absolutive collective is the citation form. Number is presented differently to other languages with consonantal roots, i.e. Afro-Asiatic languages, and is formed through mainly regular vowel apophony.

Finally, there are three genders the masculine (m), feminine (f) and neuter (n). The masculine and feminine are not distinguished in the plural declension and in the plural verb conjugations, instead called the common (c) gender.

Gender

As previously stated, there are three genders, the masculine (m), feminine (f) and neuter (n), where the masculine and feminine may syncretise into the common gender (c or m/f) in complex inflections. Gender plays important roles in both nominal and verbal inflections, since verbs conjugate according to gender as well.

It is important to note that while verbs agree according to gender, valency decides what argument the verb agree with. Intransitive verbs agree with the subject, transitives with the object, and ditransitives get their direct object incorporated, and then agree with the gender of the direct object. Further information is found later on the page under "Verbs".

Case

Core cases

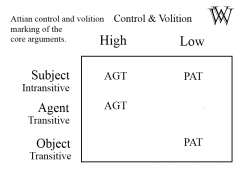

The Attian language is an active-stative language with fluid subjects, dependent upon semantic volition or control. This means that it marks the object of a transitive verb and the subject of a intransitive verb the same - with the patientive case - and mark the agent of the transitive separately, with the agentive case. The fluid subtype however, declares that the subject of an intransive verb, may be marked like the agent of the transitive, if the subject has sufficient control over the action.

Patientive

The patientive, or undergoing case, (pat) is the case used to indicate both the subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a transitive verb, in addition to being used for the citation form of nouns.

The patientive is marked inflectionally on the noun, but the since Attian possesses no patientative personal pronouns, but rather enclitic pronouns, these are used to mark the object of a transitive verb, and subject of a low-control intransitive verb. In addition, the usage has been expanded, and the enclitic pronouns also serves as a possessive suffix, when agglutinated to nouns.

| ginann | amnva ginann | eta anthva atna mina | |||||||||||

| /ˈɡinanː/ | /a'ŋ͡ma ˈɡinanː/ | /ɛtˈa anˈθwa atˈna ˈŋina/ | |||||||||||

| gina | -nn | amn | -va | gina | -nn | eta | anth | -va | atn | -a | mina | ||

| trip/ind.dyn.1.f.sg | -pat.1.sg | you/1.m.sg | -m.agt | trip/ind.dyn.1.f.sg | -pat.1.sg | this/prox.sg.m | man/m.sg. | -m.agt | dog/m.sg. | -m.pat | see/ind.dyn.1.m.sg | ||

| I trip | You trip me | This man sees a dog | |||||||||||

Using just the patientive enclitic on mediopassive verbs gives a reflexive or passive meaning. With the mediopassive voice, the reflexive usage is normally implied when the subject is the patient. In colloquial speech however, the distinction between passive and reflexive is most often blurred.

| thunann | gva thuna | ta myayu dune | ta myau dune | |||||||||||||

| /ˈθunanː/ | /ˈɡwa ˈθuna/ | /ŋjaju ˈdune/ | /ˈŋjau̩ ˈdune/ | |||||||||||||

| thuna | -nn | g | -va | thuna | ta | mya | -yu | dune | ta | mya | -u | dune | ||||

| speak/med.gn.m.sg | -pat.1.sg | I.1.sg.m | -m.agt | speak/med.gn.m.sg | the.def.n | cat/n.sg | -pat.3.sg | eat/med.dyn.n.sg | the.def.n | cat/n.sg | -n.agt | eat/med.dyn.n.sg | ||||

| I speak of myself or I am being spoken of | I am being spoken of | The cat is eating itself

|

The cat is being eaten | |||||||||||||

Agentative

The agentative (agt) case is used to mark the subject, or agent, of transitive verbs. However, intertwined with the Attian language's distinction on control and volition, there is a slight intentional distinction on intransitives, marking high control intransitives through the agentative argument. Confer the difference betweem the English intransitives "He tripped" and "He talked". In Attian, the former argument would be marked with the patientative case, since he is undergoing the verb, and the latter would be marked with the agentative, since he is in full control of his actions and the agent of the verb.

Being a fluid-S language, however, the simple "He tripped", might be marked with the agentative, should he intentionally have done so. Most often, this conveys a slight semantic shift, and "He tripped" might be interpreted as "He's faking a fall". Some verbs are are inherently high control, for example, the dynamic action "to cook", zama, can hardly be performed unintentionally, likewise is the word for "to talk", thana, somewhat difficult to perform involuntarily, except for sleep-talking.

The semantic shift is illustrated below with the word "to breathe", which may be interpreted differently, depending on whether marked with the patientive enclitic pronoun, or the agentive personal.

| himamn | amnva hima | hamamn! | amnva ham! | |||||||||

| /ˈhiŋ͡møŋ͡m/ | /aŋ͡mˈa ˈhiŋ͡mø/ | /ˈhaŋ͡møŋ͡m/ | /aŋ͡mˈa haŋ/ | |||||||||

| hima | -mn | amn | -va | hima | ham | -amn | amn | -va | ham | |||

| breath/ind.dyn.m.sg | -pat.2.sg | you/.2.m.sg | -m.agt | breathe/ind.dyn.m.sg | breathe/dir.pos.m.sg | -pat.2.sg | you/.2.m.sg | -m.agt | breathe/dir.pos.m.sg | |||

| You are breathing. (involuntarily, subconciously) |

You are breathing. (intentionally, "breathing heavily") |

Breathe! (as in "to start breathing") |

Breathe! (as in "calm down") | |||||||||

When high-control intransitives are marked with the agentive case - as in the case "to cook" - the direct object may be left unmentioned, granted that the gnomic aspect is used. This implies the cooking of something, instead of directly mentioning it. If there is doubt whether an action is performed intentionally or involuntarily, the agentive is generally used.

| minim azmim | minim ta mithra izmim | ta ramva aramia | ||||||||||

| /ˈŋiniŋ azˈŋiŋ/ | /ˈŋiniŋ ta ˈŋiθr̥a izˈŋiŋ/ | /ta ˈraŋ͡ma ˈr̥iŋej/ | ||||||||||

| minim | azmim | minim | va | mithr | -a | izmim | va | ram | -va | rimey | ||

| you/agt.1.c.pl | cook/ind.neu.c.pl | you/agt.1.c.pl | the.def.n | squirrel/n.sg | -n.pat | cook/ind.dyn.c.pl | the.def.n | bird/n.sg. | -m.agt | fly/ind.stat.n.sg | ||

| You cook (something) | You are cooking a squirrel | The bird flies | ||||||||||

Instrumental

Instrumental proper

The instrumental (ins) case serves a number of purposes in the Attian language. Primarily, it is used to indicate that a noun is the instrument or means by or with which an action is conducted.

| gva va gramma gennan gira | |||||||

| /ɡwa wa ˈkr̥aŋ͡mø ˈk͡pœœnːan ˈɡira/ | |||||||

| g | -va | va | gramm- | -a | kvenn | -an | gira |

| I.1.sg.m | -m.agt | the.def.n | letter.n.sg | -pat.n.sg | pen.m.sg | -m.ins | write/ind.dyn.m.sg |

| I write the letter with a pen | |||||||

| atva utagavun aggim | inaratrin nurimni | |||||||

| /atˈwa utˈaɡøwun aɡˈɡiŋ/ | /inˈaratr̥in ˈnuriŋ͡mi/ | |||||||

| at | -va | ⟨u⟩tagav⟨un⟩ | aggim | inaratra | -in | nurimn | -mni | |

| we/1.c.pl | m.agt | ⟨n.ins⟩boat/n.col⟨n.ins⟩ | go/ind.gn.c.pl | happiness/f.sg | -f.ins.sg | gladden/med.dir.c.pl | -2.pat.f.pl | |

| We go by boat | Let happiness make you glad! - Attian saying. | |||||||

Inanimate subjective instrumental

On subject of control in the Attian verbs, inanimate agents of transitive verbs: subjects such as "the knife" in the sentence "The knife slices the bread" could impossibly be marked with the agentive case, since the subject has no control of its actions. Nor is it experiencing the slicing, and can as such not be marked with the patientive. Instead a construction with the mediopassive and instrumental used.

Of course if desired, the agent can be reintroduced, which means a switch from passive to active.

| gva rega amagvan gava | uvanun tutann | ||||||||||

| /ˈɡwa ˈr̥ɛɡa aŋˈaɡwan ˈɡøwa/ | /uˈwana ˈtutanː/ | ||||||||||

| g | -va | ury | -a | a- | magv | -an | gava | ⟨u⟩vaun⟨un⟩ | tuta | -nn | |

| I.1.sg.m | -m.agt | bread/col.n. | -n.pat | m.ins- | knife/col.m. | -m.ins | cut/ind.neu.m.sg | ⟨n.ins⟩stone/n.col⟨n.ins⟩ | hit/med.dyn-stat.m.sg | --pat.1.sg | |

| I cut bread with knifes | I am hit with stones | ||||||||||

Marking the inanimate noun with the agentive is incorrect. This is a distinction quite well known in natural languages, and even the Proto-Indo-European language is supposed to have made the distinction.

| vanev ittimann | vanun tutinn | yatva vanum titann | |||||||||||||

| /ˈwanɛw itˈtiŋanː/ | /ˈwanun ˈtutinː/ | /ˈjatwa ˈwanuŋ ˈtitanː/ | |||||||||||||

| vana | -ev | ittim | -ann | vana | -un | tuti | -nn | yat | -va | vana | -um | tita | -nn | ||

| stone/n.pl. | -n.pl.agt | hit/ind.dyn.n.pl | --m.pat.1.sg | stone/n.pl | -n.pl.ins | hit/med.dyn-stat.m.sg | --m.pat.1.sg | someone/m.sg | -m.agt | stone/n.pl | -n.pl.ins | hit/ind.dyn.m.sg | --m.pat.1.sg | ||

| *Stones hit me | I am hit with stones | Some guy hits me with stones | |||||||||||||

Comitative instrumental

The Attian instrumental also bears comitative and quantitative senses, indicating actions in company with other subjects, amounts, as well as lacking:

| amnayya gan? | gva amnan imgimna | gvayya yarmunan | ||||||||||||||||

| /aˈŋ͡majːa ɡøn/ | /ɡwa aˈŋ͡man iŋˈɡiŋ͡ma/ | /ˈɡwajːa ˈjar̥ŋunan/ | ||||||||||||||||

| amn | -a | -yya | g | -an | g | -va | amn | -an | imgim | -na | g | -va | -yya | yarm | -un | -an | ||

| you/2.sg.c | -c.pat.sg | -cop.act.ind.stat | I/1.sg.m | -m.ins | I/1.sg.m | -m.agt.sg | you/2.sg.c | -m.ins | make/act.ind.dyn.c.pl | --pat.3.n.sg | I/1.sg.m | -m.agt.sg | -cop.act.ind.stat | hair/n.sg | -n.ins | -n.neg | ||

| Are you with me? | I make it with you. | I am with no hair. or I have no hair. | ||||||||||||||||

Animate subjective instrumental

The last use of the instrumental, similarly to Russian and in part to English is to reintroduce a subject in a passive clause, very similarly to the adpositional phrase "by me" in English, as in "He was killed", and later; "He was killed by me". Using the instrumental with a reflexive mediopassive gives a reinforced statement, confer the Spanish disjunct prepositional pronouns:

- Me lavo - «I wash myself»

- A mí me lavo - «As for myself, I wash myself»

| gva muni minan? | mumnayyiz gan | ethunann gan | |||||||||||

| /ɡwa ˈŋ͡muni ˈŋinan/ | /ˈmuŋ͡majːiz ˈɡøn/ | /ˈθunanː ɡøn/ | |||||||||||

| g | -va | muni | min | -an | mumnayyiz | g | -an | thuna | -nn | g | -an | ||

| I/1.sg.m | -m.agt.sg | see/med.ind.dyn.c.sg | you/2.pl.c | -m.ins | discover/medpcp | I/1.sg.m | -m.ins | talk/med.ind.dyn.c.sg | --m.pat.1.sg | I/1.sg.m | -m.ins | ||

| I'm seen by you |

. |

Discovered by me | Me, I speak of myself. | ||||||||||

Locative

Locative proper

- See also: Attian possession

The locative case (loc) vaguely corresponds to the English spatial prepositions of "by", "at", "in", and "on". However, the Attian locative also bears a temporal usage, similarly to English "in an hour", "today", "after three o'clock". The Attian language does not have adpositions in the traditional sense, to control the exact location of the locative, but rather proclitics. These will be marked green.

| Amnayya azimat? | ʔineyna enazamut. | amagyat | |||||||||||

| /aˈŋ͡majːa azˈiŋ͡mat/ | /ˈʔinɛjna ɛnˈazaŋut/ | /aŋaɡˈjat/ | |||||||||||

| amna | -yya | azima | -t | ʔiney | -na | en- | azama | -ut | am- | agy | -at | ||

| you/2.sg.c.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | home/sg.n | -n.loc | lie/act.ind.stat.n.sg | -it/n.pat.3.sg | below.locp- | house/2.sg.c | -n.loc | after/behind.locp- | hour/f.sg | -f.loc | ||

| Are you at home? | It lies below the house. | In an hour | |||||||||||

Lative locative

Related to location is movement, and the locative can through a construction with the lative particle ‹a› /a/, transform the locative meaning to a lative or translative one. Before a null-onset, it is pronounced /aɦ/.

The particle and the proclitic adpositions will be marked green.

| Gam a azimat! | ʔinena a enazamut. | Ann erʔit. | |||||||||||||

| /ɡøŋ aɦazˈiŋat/ | /ˈʔinɛna aɦ ɛnˈazaŋut/ | /anː erˈʔit/ | |||||||||||||

| gam | a | azima | -t | ʔine | -na | a | en- | azama | -ut | a- | -nn | erʔi | -t | ||

| come/act.dir.pos.m | latp | home/sg.f | -f.loc | lay/act.ind.dyn.n.sg | -it/n.pat.3.sg | latp | below.locp- | house/n.sg | -n.loc | latp | -m.pat.1.sg | anger/f.sg | -f.loc | ||

| Come home! | Put it below the house. | I am getting angry. | |||||||||||||

Possessive locative

The third purpose of the locative case is that it is also the main tool to express possession, a construction very close to the Celtic and Finnish equivalents, confer:

- Minulla on talo - I have a house (literally: There is a house at me)

This is the one of the ways of expressing alienable possession in Attian, and it is as such never used for inalienable constructions.

| gat azamayya | Manim gat azamayya! | ||||||||

| /ˈɡ͡bøt aˈzaŋajːa/ | /ˈŋ͡mønin ˈɡ͡bøt aˈzaŋajːa/ | ||||||||

| g | -at | azama | -yya | emin | g | -āt | azama | -yya | |

| I/1.sg.m | -c.loc | home/sg.n.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | see/act.dir.pos.c.pl | I/1.sg.m | -c.loc | home/sg.n.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | |

| My house | Behold my house! | ||||||||

| azamayya gat ta trasino | Atnvayya gat girgemn. | ||||||||||||

| / aˈzaŋajːa ˈɡ͡bøt wa taˈtr̥asino/ | / atˈŋ͡majːa ˈɡ͡bøt ˈɡirɡemn/ | ||||||||||||

| azama | -yya | g | -at | ta | trasino | atn | -va | -yya | g | -at | girge | -mn | |

| home/sg.n.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | I/1.sg.m | -f.loc | def art.n | green(n.sg.pat) | dog/sg.n | -agt.n.sg | -cop.act.ind.stat | I/1.sg.m | -f.loc | see/act.ind.dyn.n.sg | -you.m.pat.2.sg | |

| My green house | My dog barks at you. | ||||||||||||

Number

Several's more than one

Singular

The singular (sg) number is the most basic form of most nouns, and marks individual nouns, counting "one". It is completely corresponding to the English equivalent. The singular patientive is the citation form of all nouns in the Attian language. The singular inflects according to three genders, masculine, feminine and neuter.

In the locative the vowel is dependent on gender, granting an ⟨a⟩ or a ⟨u⟩ if masculine/feminine or neuter respectively. Final vowels are assimilated.

| Patientive | Agentive | Instrumental | Locative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | -∅ | -va | -an | -Vt |

| Feminine | -∅ | -vi | -in | -Vt |

| Neuter | -∅ | -u | -un | -Vt |

| Examples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patientive | Agentive | Instrumental | Locative | Meaning | |

| Masculine | magra | magarva | magran | magrat | knife |

| Feminine | tazu | tazvi | tazan | tazat | horse |

| Neuter | thena | thenu | thenun | thenut | speech |

Collective

The collective (col) number of nouns indicates an unspecified, indefinite, general nominal amount. The introduction of this number into the language was meant to tie in with the genereic aspect of the verbs. In English, nouns of this kind most often receives a plural marking, such as "people say stupid things" or "birds can fly". Unlike other languages with the collective number, it is not the least marked and basic number, but it is still widely used. The collective inflects according to two genders, common and neuter.

Please note that collective nouns always agree with the third person plural of nouns, and that pronouns do not inflect to the number. The following table details the three vowel classes and their declension in the collective number.

- The collective is primarily formed through an insertion of either an /a/ or /u/ initially, depending on vowel class. If the noun has a null-onset, the initial vowel is assimilated.

| Patientive | Agentive | Instrumental | Locative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common | a-V | a-ia | a-an | a-Vt |

| Neuter | u-V | u-ey | u-un | u-Vt |

| Examples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patientive | Agentive | Instrumental | Locative | Meaning | |

| Masculine | amagra | amagria | amagran | amagrat | knife |

| Feminine | atazu | atazia | atazan | atazat | horse |

| Neuter | uthena | utheney | uthenun | uthenat | speech |

Plural

The plural (pl) number refers to any objects counting more than "one", that is "several". It corresponds well to the English plurals. The plural formation is radically (...) different to the collective and singular:

- Initial vowels are deleted.

- If no initial vowel, it grants either an /i/ or /u/, depending on gender, after the first radical

- The penultimate vowel of triliterals and quadriliterals are deleted.

The plural inflects according to two genders, common and neuter.

| Patientive | Agentive | Instrumental | Locative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common | -im | -ay | -an | -at |

| Neuter | -um | -ev | -un | -ut |

| Examples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patientive | Agentive | Instrumental | Locative | Meaning | |

| Masculine | migrim | migray | migran | migrat | knife |

| Feminine | tizim | tizay | tizan | tizat | horse |

| Neuter | thunum | thunev | thunun | thunut | speech |

Animacy

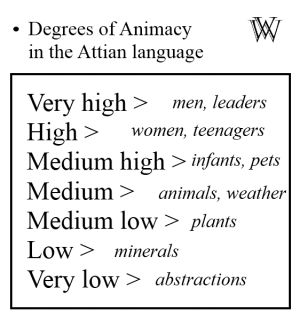

Just as the Attian language makes a difference regarding gender, a fairly strong distinction in animacy[*] is made, mainly for semantical and grammatical reasons, since there is no morphological distinction.

The Attian animacy dictates that no inanimate objects may stand in the agentative case. Inanimate nouns are perceived as incapable of actually performing deliberate actions. Inanimates that are the subjects of an action are therefore most often marked with the instrumental case. This construction forces the speaker to directly name an animate agent, use a passive construction, or to use an indefinite pronoun. Inanimate, or less animate nouns also have a lesser probability to be compatible with verbs connected with higher degrees of animacy, like the words for "to talk", "to think" and "control".

There are several different degrees of animacy, which at times also intertwine with salency. The grading goes from Very high to Very low and spans 7 degrees. The top and most animate nouns are humans, and especially men and leaders. Women normally rank as at least as animate as men, but they can in certain circumstances be degraded to indicate inferiority. The least animate substantives are minerals, abstraction and in part; plants.

Don't blame the stone

Below is an example of someone hit with stones. Here, the subject impossibly could be marked with the agentive, taking their inanimacy in regard. Instead, you may put the subject in the instrumental case, and mediopassivise the verb. Alternatively the subject is degraded to an oblique, and a new subject is introduced.

| vanev ittimann | vanun tutinn | yatva vanum titann | |||||||||||||

| /ˈwanɛw itˈtiŋanː/ | /ˈwanun ˈtutinː/ | /ˈjatwa ˈwanuŋ ˈtitanː/ | |||||||||||||

| vana | -ev | ittim | -ann | vana | -un | tuti | -nn | yat | -va | vana | -um | tita | -nn | ||

| stone/n.pl. | -n.pl.agt | hit/ind.dyn.n.pl | --m.pat.1.sg | stone/n.pl | -n.pl.ins | hit/med.dyn-stat.m.sg | --m.pat.1.sg | someone/m.sg | -m.agt | stone/n.pl | -n.pl.ins | hit/ind.dyn.m.sg | --m.pat.1.sg | ||

| *Stones hit me | I am hit with stones | Some guy hits me with stones | |||||||||||||

Both verbs and nouns have different inherent animacy. Both the type of noun and verb are thus essential to interpret whether it can be the in the agentative case. Some verbs are more inherently animate than others in the Attian language, determining whether inanimate subjects may perform them; the word "to speak", thana, is used unexclusively for humans. Less animate subjects cannot perform this verb and are therefore coupled with another, more appropriate, one. Please note that only because inanimate nouns are less likely to perform more animate actions, more animate nouns may act out inanimate verbs.

Below is table with example nouns and verbs with their respective animacy. Please note that the first two degrees most often intertwine. It is common for slightly sexistic or separatistic speakers to use work-arounds when speaking about women or children: Instead of saying that they are capable, they would say they can do (it). In other terms; stative or generic verbs describing characteristics are less likely to be used with women. They have to satisfy with the appropriate dynamic verb.

| Degrees of Animacy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very High | High | Medium high | Medium | Medium low | Low | Very low |

| man | women, children | infants, pets | animals, weather | plants | minerals | abstractions |

| to talk | to communicate | to bark, to be noisy | to be green | to be heavy | to be complicated | |

Possession

Attian possession is quite complicated, and there are no less than five equally standard ways of expressing it. Which one to chose is highly dependent upon the alienablilty, and thus animacy, of the possessed object.

The alienability bears the meaning that objects or traits that can be removed from your possession are alienable, whilst objects that are inherent, traits, or if it's the origin of an object are inalienable, and always connected to you. A few English examples:

| English equivalents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alienable | Inalienable | ||

| Example | Comment | Example | Comment |

| My book | The one I bought. | My book | The one I wrote. |

| The family's house | Her arm | ||

| Our dog | The man's appearance | ||

| Her look | Her temporary look. | His impatience | |

| The girl's hair | My mother | ||

The distinction leads to two different types of possession, one which shows alienable possession, and one that indicates inalienable. Possession ties in with the animacy, as well as the active-stative morphosyntactic alignment.

The inalienable possession is indicated through suffixing the patientative enclitic pronouns to the noun stem, if the possessor is personal. If not, the locative is used on the possessor, without any adpositions.

| nathinn | an anna mihat | an emni anthat | ||||||||||

| /ˈnaθinː/ | /anˈanːa ˈŋiɦat/ | /an ɛˈŋ͡mi anˈθat/ | ||||||||||

| nathi | -nn | an | anna | miha | -at | an | emni | natha | -at | |||

| hand/sg.f.pat | --m.pat.1.sg | the.def.f | mother/sg.f.pat | girl/sg.f | -f.loc | the.def.f | appearance/sg.f.pat | man/sg.m | -m.loc} | |||

| My hand | The girl's mother | The man's appearance | ||||||||||

Alienable possession on the other hand can be marked quite differently, or rather not marked at all. Alienable possession is expressed throught the verb thama - own or control, which is equivalent to to have in English.

| Gva etiza thimay | Nihva atna ethimey | Tim nithay mānrum ithmayim | |||||||||

| /ɡwa ɛtˈiza ˈθiŋaj/ | /ˈnihwa atˈna ɛθiŋej/ | /tiŋ ˈniθaj ŋ͡mønr̥uŋ iθˈŋajiŋ/ | |||||||||

| gva | etiza | thimay | nihva | atna | ethimey | tim | nithay | mānrum | ithnayim | ||

| I/1.sg.m.agt | horse/f.sg.pat | control/ind.stat.m.sg | girl/f.sg.agt | dog/n.sg.pat | control/ind.stat.f.sg | def art.pl.m.agt | man/m.pl.agt | book/n.pl.pat | control/ind.stat.c.pl | ||

| I own a horse. | The girl has a dog. | The men have books | |||||||||

This ties in with animacy - alienable possession is not possible for inanimate nouns, since they are not perceived to be able to control or own anything. Instead, this is circumvented throughother expressions, most often with the instrumental and a copula. This is a common way of expression for animate nouns as well, but the previous example is impossible for inanimate ones.

| atnan māthmayya | māgrin mānthayya | |||||||||

| /atˈnan ˈŋøθŋajːa/ | /ˈŋøgrin ˈŋønθajːa/ | |||||||||

| atn | -an | mathma | -yya | magra | -in | mantha | -yya | |||

| dog/sg.n | -n.ins | leash/n.sg.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | knife/sg.n | -n.ins | handle/n.sg.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | |||

| The dog has a leash / A leash is with the dog | The knife has a handle / A handle is with the knife | |||||||||

Pronouns

The Attian pronouns are somewhat different to to other nouns but are still derived from radicals, most often biliterals. They decline to the singular and plural numbers only but the personal pronouns or third person demonstratives do not inflect to the patientive case, a function replaced by enclitic pronouns. The first and second person distinguish the masculine and feminine in the singular, whilst the plural ones only have the common gender. The third person has a three way distinction, with masculine, feminine and neuter.

There are no proper third person personal pronouns, this role is fulfilled by the demonstratives instead.

Personal pronouns

The personal pronouns are different to other nouns, in that they do not decline to the collective number, nor the patientative case, a role instead covered by the enclitic pronouns. The first and second person singular pronouns do however decline differently depending the masculine and feminine gender. The neuter gender is not semantically distinct in the first persons.

| Personal pronouns | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number → | Singular | Plural | ||||

| Person → | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | ||

| Case ↓ | Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | ||

| Agentive | gva | egvi | amnva | emnvi | atva | minia |

| Instrumental | gan | egin | amnan | emnin | atan | minan |

| Locative | gat | egāt | amnat | emnat | atat | minat |

Enclitic pronouns

The enclitic pronouns are a complement to the personal pronouns in that they are only declined in the patientive case. The enclitic patientive pronouns are, other than marking that the subject or object is the patient of an action, also used to mark inalienable possession.

- The initial vowel is an epenthic one, and it is deleted when the clitic is added to a word ending in another vowel.

The etymology for the enclitics are divided; the second person clitics are derived from the second person personal pronouns, and the root √m-n, to see. The first and third person clitics are different in that they are believed to be derived from the lative uniradical √n, at something.

| Enclitic pronouns | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person → | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |||||

| Number ↓ | Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

| Case → | Patientive | |||||||

| Singular | -ann | -enn | -amn | -emn | -ana | -eni | -ana | |

| Plural | -anim | -enim | -amna | -emni | -anum | -enum | -anum | |

Demonstratives

The demonstrative pronouns function as demonstratives, determiners, and third person personal pronouns. There is no distinction made, what so ever.

The feminine demonstrative pronouns have been subjected to loaning, explaining the diverseness in roots. However, the remaining roots are derived from the root √t, which is translated as one, pertaining to unity.

Distal demonstratives

The distal demonstratives, in Attian grammar sometimes called functional articles or normal demonstratives imply a relatively far distance way from the speaker, similarly to the English deictic "that". The demonstratives have a range of functions:

- The instrumental forms transform verbal nouns to adverbs after verbs.

- The locative forms transform nouns to locational or directional adverbs after verbs.

| Distal demonstrative pronouns | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person → | 3rd | |||||

| Number → | Singular | Plural | ||||

| Case ↓ | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

| Dependent | aʾ- | eʾ- | aʾ- | aʾ- | eʾ- | aʾ- |

| Independent | ah | eh | ah | ahaʾ | ehiʾ | ahaʾ |

| Instrumental | ahan | ehin | ehen | anni | enni | henu |

| Locative | ahat | ehit | ehet | atti | etti | hetu |

Proximal demonstratives

The proximal demonstratives signify a close distance of the deictic and the speaker, equivalent to the English demonstrative "this", and it is marked through prefixing an ⟨e-⟩ to the stems of the distal demonstratives. Any collisions with vowels conclude in the deletion of the original vowel. This has led to a great deal of irregularity in the proximals.

| Proximal demonstrative pronouns | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person → | 3rd | |||||

| Number → | Singular | Plural | ||||

| Proclitic | ||||||

| e- | ||||||

| Case ↓ | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

| Agentive | eta | en/eva | etu | etim | evim | etev |

| Instrumental | etan | en | etun | etan | en | etun |

| Locative | etat | evat | etut | etat | evat | etun |

These demonstratives are however quite archaic, and are being replaced by the previously complementive proclitic ⟨e-⟩. They are still valid as pronouns, but rarely determine frases, instead replaced by the proclitic, which is added to the modified noun. Unless the word starts in a vowel, in that case, the demonstratives are preferrable.

| etu nema | enema | ||||||

| /ɛˈtʊ ˈnɛŋ͡mø/ | /ɛˈnɛŋ͡mø/ | ||||||

| e- | tu | nem | -a | e- | nem | -a | |

| prox- | this/det.prox.pat.sg.n | noun/sg.n | -pat.n.sg | prox- | noun/sg.n | -pat.n.sg | |

| «this noun» | «this noun» | ||||||

Interrogative and relative pronouns

The Attian language interrogative and relative pronouns are invariable in a number respect, but do at least differ from each other, unlike in English. The interrogative pronoun is derived from the √t root similar to the first person plural and demonstratives. The relative pronouns come from the root √y-y (existence).

The masculine and feminine has conflated into the common gender, and the declension is essentially in the collective number template.

| Pronoun→ | Interrogative | Relative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case ↓ | Common | Neuter | Common | Neuter |

| Patientive | ti | te | yi | ye |

| Agentive | atia1 | utey | ayia2 | uyey3 |

| Instrumental | atan | utun | ayan | uyun |

| Locative | ati | uti | ayi | uyi |

- Usually abbreviated to tya.

- Usually abbreviated to aya.

- Usually abbreviated to uye

Relative pronouns

Disjunctive pronouns

Reciprocal pronouns

Adjectives and adverbs

The Attian language lacks simple modifiers in the traditional English sense. Adjectives and adverbs do not exist. Instead, nouns and verbs are modified through the use of nouns.

Adjectives

Adverbs

Attian adverbs are remains of system of cognate accusatives which modiied verbal phrases. Now, it is a fairly simple system using a demonstrative and a noun.

Verbs

Verbal components

Attian is an agglutinating and nonconcatenative language. Agglutination means that affixes each express a single meaning, and they usually do not merge with each other or affect each other phonologically, and nonconcatenative means that certain functions of the verb are expressed through changes in the stem. Each verb is formed by primarily changing the stems form, and secondarily by adding prefixes or suffixes to the verb stem. The components of an Attian verb occur in the following order:

| negator | evidentiality circumfix | VERB STEM | evidentiality circumfix | (copula) | patientive |

|---|

Tense

The first thing you need to know about the Attian language and its verbs, is that there is no morphological distinction of tense. Whilst the language is rather agglutinative and very synthetic, temporal tense is marked through the addition of adverbs, which themselves in practice are nouns. There are a multitude of adverbs describing different tenses and points of occurrence, and many have several meanings. Below is a sample:

| Word | Primary meaning | Temporal meaning | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| anza | אנזְ | morning/early | past | n |

| agmā | אגםְ | evening/late | future | n |

| mēgā | מֵגְ | time/timely | present | n |

| -igimā | יגִםְ- | that comes | reiterative | - |

| mēgigime | מֵגִגִםֵ | time that comes/again | reiterative present | n |

| -itiya | יטִיְ- | that waits | "relative" | - |

| mēgitiye | מֵגִטִיֵ | time that waits/today | hodiernal | n |

| anzitiye | אנזִטִיֵ | morning that waits/yesterday | hesternal | n |

| agmitiye | אגמִטִיֵ | evening that waits/tomorrow | crastinal | n |

- Please note that as with all adverbs, the definite article is compulsory, as well as the instrumental case. As with all words with an onset, the definite article is inverted.

Gender and number

The Attian verbs conjugate per gender and the two numbers singular (sg) and plural (pl). Nouns in the collective number count as plural. There are three genders in the singular; the masculine (m) feminine (f) and neuter (n). In the plural conjugation, the masculine and feminine are conflated, into the common (c) gender.

Mood and Voice

There are 3 different moods in the Attian language, the indicative, interrogative and directive moods. The directive mood, equivalent to the English imperative, conjugates according to gender, number and polarity. That is, whether the statement is negative or positive.

Concerning voices, there are two of them, equally used, and with a slight semantic difference in both usage and meaning. These are the active, and the mediopassive.

Indicative

The indicative mood (ind) is used for factual statements and positive beliefs, for example, "Mikhail doesn't like apples." or "Dimitriy eats apples." All clauses Attian language does not categorise as another mood are classified as indicative. It is the most commonly used mood and is found throughout all languages.

Interrogative

The interrogative mood (int) is used for interrogative clauses, that is, questions. It is a widely used mood, and is also peculiar in that it encompasses many conditional uses. It does thus describe a hypothetical state of affairs, or an uncertain event, that is dependent on another set of circumstances, although mainly used for asking questions.

Deontic

The deontic (deo), or directive (dir) mood, refers to a mood that indicates how the world ought to be, according to certain norms, expectations, speaker desire, et. c. A sentence containing the deontic modal generally indicates some action that would change the world so that it becomes closer to the standard or ideal. This includes commands, orders, wishes and promises.

Similar in many ways to the imperative mood in English, the Attian deontic is by far more versatile. Whilst the English mood is rather restricted to commands, the deontic replaces many clauses otherwise expressed through modal verbs. It is generally divided into three parts:

- Commissive (the speaker's commitment to do something, like a promise or threat): "I shall help you."

- Directive (commands, requests, etc.): "Come!", "Let's go!", "You've got to taste this curry!"

- Volitive (wishes, desires, etc.): "If only I were rich!"

The diverse definition of the mood implicates that usage of it is less rude than when expressing commands and wished through the English imperative.

Active voice

In Attian, as well as in many nominative-accusative languages, the active voice is used in a clause whose subject expresses the agent of the main verb. That is, the subject does the action designated by the verb. This is the default voice of the language, but it is still far less commonly used than the English active.

Mediopassive voice

Attian has another voice than the active; the mediopassive. In contrast to the active, a sentence in which the subject has the role of patient or theme is called a passive sentence, is expressed in the passive voice. In addition, should the passive encompass reflexive meanings, it is called the mediopassive.

The mediopassive is a catch-all diathesis which describes a multiple of equivalent English functions. The mediopassive has passive, reflexive, ergative, stative and reciprocal meanings, and is certainly at least as commonly used as the simple active. In many cases, the mediopassive may implicate a complete semantic shift - a change in meaning.

To provoke a reflexive or passive meaning from a verb, one may use the patientive with the mediopassive without introducing the agent of the clause. With the mediopassive voice, the reflexive usage is normally implied when the subject is the patient, and when using the agentive pronoun or noun the verb is perceived as passive. In colloquial speech however, the distinction between passive and reflexive is most often blurred, and the patientive takes on both uses.

| thuninn | gva thuni | ta myana dunu | ta myau dunu | |||||||||||||

| /ˈθuninː/ | /ˈɡwa ˈθuni/ | /taˈŋjana ˈdunʊ/ | /taˈŋjau̩ ˈdunʊ/ | |||||||||||||

| thuni | -nn | g | -va | thuni | ta | mya | -ana | dunu | ta | mya | -u | dunu | ||||

| speak/med.dyn-stat.m.sg | -pat.1.sg | I.1.sg.m | -m.agt | speak/med.dyn-stat.m.sg | the.def.n | cat/n.sg | -pat.3.sg | eat/med.dyn-stat.n.sg | the.def.n | cat/n.sg | -n.agt | eat/med.dyn-stat.n.sg | ||||

| I speak of myself or I am being spoken of | I am being spoken of | The cat is eating itself

|

The cat is being eaten | |||||||||||||

As a tie-in with the very prevalent animacy in the language, the mediopassive well may be used to form ergatives. Since the Attian agent must be animate, this circumvention eliminates the agent, leaving the inanimate in the patientive similar to a reflexive or passive. The ergative works with animates as well, but the application on inanimates is more common.

| ta munehna guthu | raiaya vuhu | |||||

| /ta ˈŋunɛhna ˈguθʊ/ | /r̥aˈi̩aja ˈwuhʊ/ | |||||

| ta | munehna | guthu | raia | -ya | vuhu | |

| the.def.n | window/n.sg.pat | break/med.dyn-stat.n.sg | head/n.sg.pat | -m.pat.3.sg | turn/med.dyn-stat.n.sg | |

| The window broke | His head turns | |||||

| ta tata zuzim | ta genan gunun | |||||

| /taˈtata ˈzuziŋ/ | /taˈɡ͡bœnan ˈgunun/ | |||||

| ta | tata | zuzim | ta | genan | gunun | |

| the.def.n | dad/m.sg.pat. | move/med.dyn.c.sg | the.def.n | song/n.sg.pat | sung/med.dyn.n.sg | |

| «The dad moves»

|

«*The song sung» | |||||

Somewhat interestingly, but foremost confusingly, perhaps amazingly, the mediopassive has an affect on semantics, most often through the forming of statives, or rather predicatives. Attian does have a stative aspect, which forms true statives - confer the dynamic "I hang my coat on the chair", versus the stative "I hang on the wall". Predicatives instead form expressions similar to "I am famous" or "It is wild". This is also the only slight adjectival distinction in the language, since the mediopassive can only confer a predicative meaning of traits, and not of objects. Thus, sentences like "I am hungry" are possible, but "It is hunger" is not viable to construct through the mediopassive.

- Predicative arguments always use the agentive case.

| emnvi muna | atnva tune | gva muga | minia urrim | |||||||||||

| /ɛˈŋ͡mi ˈŋ͡muna/ | /atˈŋ͡ma ˈtunɛ/ | /gwa ˈŋuɡ͡bø/ | /ˈŋinia ur̥ˈr̥iŋ/ | |||||||||||

| emn | -vi | muna | atn | -va | tune | g | -va | muga | min | -ia | urrim | |||

| You.2.sg.f | -m.agt | see/med.neu.c.sg | dog/.sg.n | -n.agt | rage/med.neu.n.sg | I.1.sg.m | -m.agt | do/med.neu.c.sg | We.1.pl.c | -c.agt | lead/med.dyn-stat.c.pl | |||

| «You are famous» | «The dog is wild» | «I am done»

|

«We are first» | |||||||||||

Aspect

The Attian verbal system is based mostly on the aspectual distinctions, of which there are 4. Depending on what verbal template is being used, the verbs aspects may be limited, extended or replaced. There are however still only four basic aspects.

Neutral

The neutral, or sometimes gnomic or generic, aspect (gen, neu, gn) is an Attian aspect which expresses general truths, aphorisms and empiric facts. The neutral or gnomic aspect stands in opposition with the episodic aspects which are defined for a certain time. Whilst the Attian neutral aspect is applicable to all tenses, it is most often used without a tense marker. Thus, it differs to the imperfective aspect, which can be expressed when the neutral aspect is coupled with an adverb denoting tense.

The neutral aspect is also often coupled with the collective number, signifying undefined amounts of subjects. The collective number still counts as plural in conjugations, however.

| Arru armey remnum. | Anaria adnim anzan uyatan ta atan. | ||||||||

| /ar̥ˈr̥ʊ ar̥ˈŋɛj ˈr̥ɛŋ͡muŋ/ | /anˈaria adˈniŋ anˈsan uˈjatan taˈtan/ | ||||||||

| arru | armey | remnum | anaria | adnim | anzan | uyatan | ta | atan | |

| all/det.inv. | bird/n.col.agt | fly/ind.neu.n.pl | person/c.col.agt | eat/ind.neu.c.pl | past.det | game/n.col.pat | def.art.n | one/n.sg.ins | |

| All birds fly. | People used to only eat game. | ||||||||

Stative and dynamic

The stative aspect (stat) is an Attian aspect used on verbs to express a stative perspective of a verb, if any. The aspect marks verb with an inherent sort of property, sometimes permanent, nevertheless marking a state. Most statives are intransitive.

The dynamic (dyn) aspect on the other hand signifies an action, perceptual, physical or the like, and they differ from statives in that they imply movement or a undefined duration. Confer the difference between stative and the opposing dynamic verbs:

- You are hanging (from a cliff) - stative

- You are hanging (a painting on the wall) - dynamic

The stative aspect is only distinguished in the active voice. In the mediopassive, it merges with the dynamic aspect. The mediopassive in itself is a common substitute for the stative aspect.

| Emnvi ta azama ethiri. | Ta azama thirey. | Ta azama thuru. | |||||||||

| /ɛˈŋ͡mi tasˈaŋa ɛθˈiri/ | /tasˈaŋa ˈθirɛj/ | /tasˈaŋa ˈθurʊ/ | |||||||||

| emnvi | ta | azmu | ethiri | ta | azmu | thirey | ta | azmu | thuru | ||

| you/2.sg.f.agt | the/def.art.n.sg | house/n.sg.pat | burn/ind.dyn.f.sg | the/def.art.n.sg | house/n.sg.pat | burn/ind.stat.f.sg | the/def.art.n.sg | house/n.sg.pat | burn/med.dyn-stat.f.sg | ||

| You burn the house. | The house burns. | The house is being burned. | |||||||||

Momentane

The momentane aspect (mom), also known as the "aspect of the past" is a peculiar aspect in the Attian language. It indicates that an occurrence is sudden and short-lived, and occurs at a specific and perfective point of time. Confer:

- The mouse squeaked. - non-momentane

- The mouse squeaked once. - momentane

| Tu titann | Tu ʾattann | Tu nitatur ʾatatur? | ||||||||||

| /tʊ ˈtitanː/ | /tʊ ˈʔatːanː/ | /tʊ ˈnitatur̥ ˈʔatatur̥/ | ||||||||||

| tu | tita | -ann | tu | ʾatta | -ann | tu | nitat | -ur | ʾatat | -ur | ||

| he/3.m.sg.agt | hit/ind.dyn.m.sg | -pat.1.m.sg. | he/3.m.sg.agt | hit/ind.mom.m.sg | -pat.1.m.sg. | he/3.m.sg.agt | hit/int.dyn.m.sg | -or/coo.conj. | hit/int.mom.m.sg | -or/coo.conj. | ||

| He hit me. | He hit me once. | Did he hit [you] once or several times?/Did he beat or strike [you]? | ||||||||||

The momentane does however shine on a different area - most of the time, the momentane works like a perfective, signifying past events, similarly to a preterite or a perfect tense and compound tense. This grants that the past tense is sometimes implied when using the momentane aspect.

It also signifies actions performed very quickly, especially in the present time.

| Ta amguh vite ta anzan. | Ta amguh vite. | |||||||||

| /taŋˈɡuɦ ˈwitɛ tanˈsan/ | /taŋˈɡuɦ ˈwitɛ/ | |||||||||

| ta | amguh | vite | ta | anzan | ta | amguh | vite | |||

| the/def.art.n.sg | mouse/n.sg.pat | squeak/ind.dyn.n.sg | the/def.art.n.sg | morning/n.sg.ins | the/def.art.n.sg | mouse/n.sg.pat | squeak/ind.dyn.n.sg | |||

| The mouse squeaked (in the past). (formal) | The mouse squeaked (or squeaks, will squeak). (colloquial) | |||||||||

| Ta amguh ʾevte. | Ta amguh ʾevte atmegan | ||||||||

| /taŋˈɡuɦ ˈʔɛwtə/ | /taŋˈɡuɦ ˈʔɛwtə atˈŋ͡mœɡ͡bøn/ | ||||||||

| ta | amguh | hevte | ta | amguh | hevte | at- | -mēgān | ||

| the/def.art.n.sg | mouse/n.sg.pat | squeak/ind.mom.n.sg | the/def.art.n.sg | mouse/n.sg.pat | squeak/ind.mom.n.sg | the/def.art.n.sg - | time/n.sg.ins | ||

| The mouse squeaked. | The mouse squeaks/squeaked rapidly today. | ||||||||

Evidentiality

Not who, not what, not where nor when. But how.

A feature not previously used in examples, although almost essential to everyday communication in Attian, is evidentiality. The definition can be cited as the indication of the nature of evidence for a given statement; that is, whether evidence exists for the statement and/or what kind of evidence exists. Simply put; it marks the source of information the speaker has for his or her statement.

There are four evidentials in the Attian language, in addition to the use of no evidential at all. These are:

- Visual - used when there is visual evidence often by the speaker himself, that something has occurred.

- Nonvisual - used when there is other evidence than visual to support an occurrence. This might be sensory, olfactory or auditory evidence or the like.

- Hearsay - when an occurrence only can be confirmed through hearsay and that it may not necessarily be accurate.

- Quotative - the quotative has a higher degree of certainty then the hearsay evidential, used when citing a second or third hand source. Most often believed to be accurate and not open for interpretation.

The process in Attian is known as embedding. The evidentials are proper biliteral roots conveying their inherent information and are circumfixed on the conjugated verb. At times, they can be circumfixed on adverbs, adjectives and nouns as well.

Visual and nonvisual

Evidentials in Attian are typically used to convey information in the past tense, although it is not granted. Especially the visual and nonvisual evidentials have this implication.

| An anithariaʾ u amnat megizin ta uhdhan | Azayya ta meterat | ||||||||||||||||

| /an anˈiθari̩aʔ ʊ aŋ͡mˈøt ˈŋ͡mœɡizin ta uhˈðan/ | /aˈzajːa taˈtɛra/ | ||||||||||||||||

| an | anithariaʾ | u | amnat | ⟨me⟩ | egizi | ⟨in⟩ | ta | uhdhan | aza | -ayya | ta | ⟨me⟩ | tera | ⟨at⟩ | |||

| the/def-art.f.sg.agt | police/f.sg.agt | from.latp | we/1.c.pl.loc | ⟨evid.vis⟩ | go/ind.dyn.f.sg | ⟨evid.vis⟩ | the/def-art.n.sg | side/n.sg.ins | outside.locp | ind.cop | the/def-art.n.sg | ⟨evid.nonvis⟩ | cold/n.sg.pat | ⟨evid.nonvis⟩ | |||

| The police went past us | It is cold outside. | ||||||||||||||||

| Or: I saw the police go past us | Or: It is cold outside, I felt. | ||||||||||||||||

Hearsay and quotative

The hearsay (hear) and quotative (quot) evidentials denot when an occurrence only can be confirmed only through hearsay and that it may not necessarily be accurate, or when used when citing a second or third hand source. Most often believed to be accurate and not open for interpretation. Compare the difference in the English phrases "It is said" and "I was told".

| Amnva ta tenia theminan. | Ta aruzayya mugayyir ta themegan | ||||||||||||||

| /aŋ͡mˈa taˈtɛni̩a ˈθɛŋinan/ | /ta arˈusaʝːa ˈŋuɡaʝːir̥ tanˈθɛŋ͡mœɡ͡bønan / | ||||||||||||||

| amnva | ta | tania | the- | mina | -an | ta | aruz | -ayya | -mugayyir | -tan | ⟨the⟩ | megan | ⟨an⟩ | ||

| you/2.m.sg.agt | def.art.n.sg. | movie/n.sg.pat | ⟨evid.hear⟩ | see/ind.dyn.m.sg | ⟨evid.hear⟩ | def.art.f.ins | rice/n.sg.pat | -cop.ind. | done/pcp.med | def.art.n.ins | ⟨evid.hear⟩ | present/n.sg.ins | ⟨evid.hear⟩ | ||

| It is said you saw that movie. | The rice is supposed to be done now! | ||||||||||||||

| Magaziniyya an ʾatemay | An aʾahagman niʾat thiya ʾagumeyamn | ||||||||||||||

| /ˈŋ͡møɡ͡bøziniʝːa anˈʔatɛŋ͡møj/ | /anˈaʔahaɡŋan ˈniʔat ˈθiʝa ʔaɡuŋ͡mœʝaŋ͡m/ | ||||||||||||||

| magazi | -ni | -yya | an | ⟨ʾa⟩ | tema | ⟨y⟩ | an | aʾahagman | niʾat | thiya | ⟨ʾa⟩ | gume | ⟨ey⟩ | -amn | |

| shop/f.sg.ins | -prox.f.sg | -cop.ind. | def.art.f.pat | ⟨evid.quot⟩ | good/f.sg.pat | ⟨evid.quot⟩ | def.art.f.ins | deprivation/f.sg.ins | sleep/f.sg.loc | sickness/f.sg.pat | ⟨evid.quot⟩ | go/ind.dyn.m.sg | ⟨evid.quot⟩ | -you/2.m.sg.pat | |

| This shop is great, I was told. | The sleep deprivation makes you sick, they say. | ||||||||||||||

Control and volition

Verbal patterns for single biradicals

| Verb | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| √m-n | mana | to see | |||||||||||

| Verbal noun | |||||||||||||

| menim | |||||||||||||

| Participles | |||||||||||||

| Active | menayyim | ||||||||||||

| Mediopassive | munayyir | ||||||||||||

| Evidentials | |||||||||||||

| Visual | me-in | Nonvisual | me-at | ||||||||||

| Hearsay | the-an | Quotative | ʾa-ay | ||||||||||

| Person | Singular | Plural | |||||||||||

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Common | Neuter | |||||||||

| Active | |||||||||||||

| Indicative | Neutral | mana | emani | mene | amnim | menum | |||||||

| Dynamic | mina | emini | mine | imnim | minum | ||||||||

| Stative | minay | eminey | miney | imnayim | mineyum | ||||||||

| Momentane | ʾamna | eʾamni | ʾemne | ʾamnim | ʾemnum | ||||||||

| Interrogative | Neutral | nimana | nemani | nemen | nimanim | nimnum | |||||||

| Dynamic | niman | enimin | nimen | nimēnim | nimenum | ||||||||

| Stative | nimnay | enimney | nimney | nimnayim | nimneyum | ||||||||

| Momentane | ʾaman | eʾamin | ʾamen | ʾamnim | ʾemenum | ||||||||

| Directive | Positive | mān | emin | men | mānim | menum | |||||||

| Negative | minin | emanin | menni | amani | amenu | ||||||||

| Mediopassive | |||||||||||||

| Person | Common | Neuter | Common | Neuter | |||||||||

| Indicative | Neutral | muna | mune | munim | munum | ||||||||

| Dyn-stat | muni | munu | umnim | umnum | |||||||||

| Momentane | uʾamna | uʾumne | uʾumnim | uʾomnum1 | |||||||||

| Interrogative | Neutral | numana | numene | numanim | numnum | ||||||||

| Dyn-stat | numan | numrn | numenim | numonum1 | |||||||||

| Momentane | ʾuman | ʾumen | ʾumnim | humonum1 | |||||||||

| Directive | Positive | mun | mon | munim | munum | ||||||||

| Negative | munin | munni | amuni | amunu | |||||||||

| Notes | |||||||||||||

| 1. ⟨o⟩ appears from vowel dissimilation. | |||||||||||||

Numerals

The Attian language is peculiar in many aspects, although its numerals are rather extreme. Interesting both to linguists and mathematicians, the language has a trivigesimal number system, that is, base 23.

| Attian | PAt | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ata | 1 | *aḱáʔ | ||||||||

| 2 | mi | 2 | *eŋʷíʔ | ||||||||

| 3 | etha | 3 | *aydáʔ | ||||||||

| 4 | teshi | 4 | *ḱeśíʔ | ||||||||

| 5 | nethi | 5 | *netʰíʔ | ||||||||

| 6 | metha | 6 | *eŋʷáydaʔ | ||||||||

| 7 | veni | 7 | *u̯ayníʔ | ||||||||

| 8 | hati | 8 | *ʔaḱáʔ | ||||||||

| 9 | naha | 9 | *naʔáʔ | ||||||||

| 10 | dani | A | *ǵaníʔ | ||||||||

| 11 | nati | B | *naḱíʔ | ||||||||

| 12 | thatshi | C | *daḱśíʔ | ||||||||

| 13 | atrai | D | *aǵr̥áɪ̯iʔ | ||||||||

| 14 | miveni | E | *eŋʷiu̯ayníʔ | ||||||||

| 15 | nagi | F | *naɡʷíʔ | ||||||||

| 16 | mihati | G | *eŋʷíʔaḱiʔ | ||||||||

| 17 | zevim | H | *saypʰíŋʷ | ||||||||

| 18 | minaha | J | *eŋʷínaʔaʔ | ||||||||

| 19 | tani | K | *ḱaníʔ | ||||||||

| 20 | midani | L | *eŋʷíǵaniʔ | ||||||||

| 21 | thaveni | M | *dau̯éyníʔ | ||||||||

| 22 | minati | N | *eŋʷínaḱiʔ | ||||||||

| 23 | naram | 10 | *nar̥ʷáŋʷ | ||||||||

| 24 | atagu naram | 11 | *aḱáʔgʷuʔ nar̥ʷáŋʷ | ||||||||

| 30 | venigu naram | 17 | *u̯ayníʔgʷuʔ nar̥ʷáŋʷ | ||||||||

| 46 | minaram | 20 | *eŋʷínar̥ʷáŋʷ | ||||||||

| 100 | migu teznaram | 48 | *ŋʷígʷuʔ ḱeśnar̥ʷáŋʷ | ||||||||

| 529 | nagim | 100 | *naɡʷíŋʷ | ||||||||

Syntax

Vocabulary

Swadesh

Swadesh list for some of the Attamian languages.