Aeranir

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

| Aeranir | |

|---|---|

| coeñar aerānir coeñar inceris | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈk̟øː.ɲar ˈɪ̃ŋ̟.k̟ɛ.rɪs̠] [ˈk̟øː.ɲar ɛːˈraː.nɪr] |

| Created by | Limius |

| Setting | Avrid |

| Native to | Telrhamir, Iscaria, Aeranid Empire |

| Ethnicity | Aeran |

Maro-Ephenian

| |

Early forms | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Aeranid Empire |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| CLCR | qco |

Aeranir, also known as coeñar aerānir (language of the Aerans), or coeñar inceris (language of the capital), is an Iscaric language in the Maro-Ephenian language group. It was originally spoken by the Aerans, developed in the deserts of Northern Iscaria in the city of Telrhamir, and spread with the expanse of the Aeranid Empire throughout Ephenia, as well as parts of Eubora and Syra. It later developed into the Aeranid languages, such as Dalot, Ilesse, Iscariano, Îredese, S'entigneis, and Tevrés. It is still used throughout Ephenia as a language of theology, science, medicine, literature, and law.

Aeranir had been standardised into Classical Aeranir by the time of the Early Empire, around the second millennia BNIA by the writer and educator Limius. The period before that is generally referred to as Old Aeranir. The language spoken between the 15th and 12th centuries BNIA is generally referred to Late Aeranir. This shift is marked by several grammatical and phonetic shifts. After that period, Aeranir began to splinter off into the various Aeranid languages. A form of Classical Aeranir called New Aeranir or Medieval Aeranir remained in use in official writings even after this period.

Aeranir is a highly inflective and fusional language, with three distinct genders, nine cases, two aspects, four moods, three persons, two or three voices, and two numbers.

History

Periodisation

The Aeranir language is descended from Proto-Iscaric, a theoretical reconstruction, which is in turn descended from Proto-Maro-Ephenian. This makes Aeranir a member of the Maro-Ephenian language family, along with Talothic, Fyrdan, and Marian. Because neither of these two proto-languages are attested in writing, it can be difficult to say when they were spoken, and when one transitioned into the other, but scholars generally agree that there was something that could be called Proto-Iscaric around the end of the 4th millennium BCA.

Proto-Iscaric was spoken by numerous Maro-Ephenian tribes which settled in Iscaria at the end of the 4th millennium. This evolved into numerous attested Iscaric languages, of which the language of the Aerans, who settled the region known as Aes, was but one. The oldest evidence of their language is found dating well after the founding of their most famous city, Telhramir, around 2500 BCA. This phase of the language, from around then to the later years of the Aeranid Kingdom, is known as Old Aeranir (called coeñar accuiha aerānir or aerānir accuiha by Classical and Golden Age sources).

Phonology

Consonants

The following is a table of phonemes in Aeranir. This analysis is based on Classical Aeranir, as it was used during the hight of the Aeranid Empire. The phonology, especially the number of vowel phonemes, varied greatly time, but this is seen as the standard version of the language.

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | lateral | plain | labial | plain | labial | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||||||

| Stop | p | t | k | kʷ | q | qʷ | |||

| Affricate | ts | tɬ | |||||||

| Fricative | f | s | h | ||||||

| Liquid | r | l | j | w | ɦ | ||||

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | lateral | plain | labial | plain | labial | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||||

| Stop | aspirated | (pʰ) | (tʰ) | kʰ | qʰ | |||||

| plain | p | t | k | kʷ | q | qʷ | ||||

| voiced | (b) | (d) | (g) | |||||||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tɬ | |||||||

| voiced | (dz~z) | |||||||||

| Fricative | f | s | h | |||||||

| Liquid | ʋ | r | l | j | ɦ | |||||

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | lateral | plain | labial | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | c | k | kʷ | |

| voiced | b | d | ɟ | g | |||

| Affricate | ts | tɬ | |||||

| Fricative | f | s | |||||

| Liquid | r | l | j | ||||

Notes on consonants

- The clusters /rh/, /nh/, and /lh/ vary greatly between dialects; [rɦ nɦ ɫɦ ~ rg ŋg ɫg ~ ʀː ŋː ʟː].

- The sequence /ks/ is written in the romanisation as x.

- The nasal consonant /n/ assimilates to the place of articulation of the following stop, so that /nk/ or /nqʷ/ for example become /ŋk/ and /ɴʷqʷ/. Before fricatives, /n/ is deleted, and the proceeding vowel is lengthened and nasalised. These processes apply between word boundries as well. Word final /n/ as part of case and personal markers is elided before a word starting with a vowel, fricative, approximate, or before a pausa. It often served as a shibboleth for discerning one's origins or social circles.

- The velar, labio-velar, and labio-uvular consonants /k/, /kʷ/, /q/, and /qʷ/ are palatalised before front vowels and /j/ to [k̟], [kᶣ], [k̠] and [k̠ᶣ] respectively. Futhermore, dental consonants /n/ and /t/ are palatalised before /j/ to [ɲ̟], and [tʲ]. The glottal fricative /h/ is also palatalised to [ç] before high front vowels and /j/. Some dialects also palatalise the postalveolar consonants /s/ and /ts/ to [ɕ] and [tɕ] before front vowels and /j/.

- The labialised consonants /kʷ/, and /qʷ/ are pronounced as truly labialised, rather than a sequence of two consonants, i.e. /kw/, /qw/. The voiced labiovelar stop only occurs after a nasal consonant.

- All consonants, with the exception of /ʋ/, can be geminated between vowels. This is denoted orthographically by doubling of the first letter of the phoneme, i.e. ⟨cc⟩, ⟨ff⟩, ⟨hh⟩, etc. The palatal approximate /j/ is always geminated to [jː] between vowels, but is written with a simple ⟨i⟩. Fricative /hː/ is usually realised as [çː]. In dialects that palatalise /s/ and /ts/, [çː] often becomes [ɕː], merging in some environments with /sː/.

- The lateral approximate /l/ has two allophones in Classical Aeranir; [l] before close front vowels, /j/, and when geminated, and [ɫ] elsewhere.

- The fricative /s/ is often pronounced further back in the mouth, closer to [s̠].

- The phoneme /h/ has two distinct allophones following the nasal /n/. When this cluster occurs natively within a word, /h/ is voiced and velarised to [g]. Nasal /n/ is likewise velarised to [ŋ]. Dialectically, the cluster /ŋg/ may be fortified to [gː] or lenited to [ŋː]. Before front vowels and /j/, these may appear as [ɲʝ], [ŋ˖g˖], [g˖ː], or [ŋ˖ː]. When the cluster /nh/ occurs where /h/ was once word initial, as result of a prefix, the nasal is deleted and the preceding vowel nasalised and lengthened, as with fricatives /s/ and /f/.

Vowels

Vowels in Aeranir underwent the greatest amount of change throughout time. Although the standard is considered to me Classical Aeranir as it was spoken in the 17th and 16th centuries bnia, this should not be seen in the context of a sliding historical spectrum. Below are listed three somewhat representative samples that provide a broad overview of general changes.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | u | uː | ||

| Mid | e | eː | o | oː | ||

| Open | a | aː | ||||

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | ɪ | iː | ʏ | yː | ʊ | uː | ||

| Mid-close | eː | øː | oː | |||||

| Mid-open | ɛ | ɛː | ɔ | ɔː | ||||

| Open | a | aː | ||||||

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | round | |||

| Close | i | (y) | u | |

| Mid-close | e | (ø) | o | |

| Mid-open | ɛ | ɔ | ||

| Open | a | |||

Notes on vowels

- The short high rounded vowel /ʏ/ is mostly a loan from Dalitian, and is not found in many native words, or words dating back to Old Aeranir. It is usually realised as [ɪ], and is only rounded in educated speech.

| PME | Old | Classical | Late |

|---|---|---|---|

| *u[r₂, r₃, h]i | → ui /ui̯/ | → y /yː/ | → i /i/ |

| *i[r₂, r₃, h]u | → iu /iu̯̯/ | ||

| *ey, *ehi, *ēy, *hey | → ei /ei̯/ | → ī /iː/ | |

| *i[r₂, r₃, h] | → ī /iː/ | ||

| *i | → i /i/ | → i /ɪ/ | → e /e/ |

| *oy, *o[r₂, r₃, h]i, *er₃i, *ōy, *[r₂, r₃, h]oy, *r₃ey |

→ oi /oi̯/ | → oe /øː/ | |

| *eh, *ē | → e /eː/ | → e /eː/ | |

| *e | → e /e/ | → e /ɛ/ | → è /ɛ/ |

| *er₂i, *r₂ey | → ai /ai̯/ | → ae /ɛː/ | |

| *ow, *o[r₂, r₃, h]u, *ōw, *[r₂, r₃, h]ow, *r₃ew, *ew, *ehu, *ēw, *hew |

→ ou /ou̯̯/ | → ū /uː/ | → u /u/ |

| *u[r₂, r₃, h] | → ū /uː/ | ||

| *u | → u /u/ | → u /ʊ/ | → o /o/ |

| *o[r₂, r₃, h], *ō, *r₃e[r₂, r₃, h], *r₃ē, *er₃ |

→ o /oː/ | → o /oː/ | |

| *o, *r₃e | → o /o/ | → o /ɔ/ | → ò /ɔ/ |

| *er₂u, *r₂ew | → au /au̯̯/ | → au /ɔː/ | |

| *er₂, *r₂ē | → ā /aː/ | → ā /aː/ | → a /a/ |

| *[r̥₂, r̥₃, h̥] | → a /a/ | → a /a/ |

- Most non-intial short vowels in Proto-Iscairc were reduced to /i/ by the time of Old Aeranir. Many of these were then further reduced in Classical Aeranir (as discussed above), to the vowels represented by diaeresis. These merged in Late Aeranir to a schwa, but this schwa was deleted in many environments.

- Old Aeranir diphthongs /ei̯/ and /ou̯̯/ may have been realised as hightened pure vowels [eː~e̝ː] and [oː~o̝ː]. Before other vowels, /ei̯/ becomes simple [e] in Classical Aeranir. Likewise, Classical /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ rise to [e] and [o] before another vowel. These were then simplified into glides [j] and [w] in Late Aeranir.

- There are two realisations of high short vowels /ɪ/ and /ʊ/ before another vowel, depending on whether the proceeding syllable it light or heavy. Following a light syllable, the become glides [j] and [w]. Follwing a heavy syllable, an anaptyctic vowel is inserted, becoming [ɪj] and [ʊw]. These vowels are not represented in the orthography.

- Some peripheral dialects of Late Aeranir retained rounded front vowels /y/ and /ø/, while in most, including the speech of Telrhamir, they merged with their plain counterparts /i/ and /e/ respectively.

Stress

Syllable stress in Old Aeranir fell uniformly on the first syllable of a word. However, by the time of Classical Aeranir, stress had shifted to a more complex paradigm, generally falling on the penult (the second to last syllable) or the antipenult (the third to last syllable). Which one was determined by the weight of the penult.

Syllables are divided into one of two categories, or weights. These are light syllables and heavy syllables. A light syllable contains a maximum of one short vowel, alone or proceeded by a consonant or consonant cluster, while a heavy syllable may contain a long vowel, a coda consonant, or both. If the penult of a word is heavy, it is stressed. If not, the antipenult is stressed.

Dialects

- Pēcilia Cūvae

- The pēcilia cūvae ('Cuvan swing') refers to the particular musical quality of the Aeranir spoken in the Aes city of Cuva (cūva) during the classical and golden age of Aeranid civilisation. It was likened in the earliest records to the pēcilia traecōvus ('talothic swing'), and occasionally referred to as the pōnus traeceus ('talothic voice'). However, by the golden age, Talothic had lost its distinct melodious accent, and the these terms fell out of use. This is believed to be the reason that citizens of Cuva were called traeceolar ('little taloths'), and is the origin of the name of the city Triggiolari, founded as Traeceolar.

- Rather than the stress-accent of standard capitoline Aeranir, the speech of Cuva is marked by a distinctive pitch accent. Pitch in Cuva begins low, and then rises until a kernel mora, after which it immediately falls. Placement of the kernel mora generally falls on the third to last mora. However, the way morae are counted is somewhat complex. A short vowel, either proceeded by a consonant or consonant cluster, or bare, counts as one mora, and a long vowel of (spurious) diphthong counts as two. On top of that, coda consonants, rather singletons or clusters, also count as a mora. So, for example, each syllable of the word āctās is three morea; a-a-c.ta-a-s

- Pitch accent manifests differently depending on where the kernel falls. Then the kernel falls on a vowel, there is a downstep before it; e.g. āctās: a-a-c.ta-a-s /àák.tààs/ [ǎːk.tàːs].

Syntax

Word order

Aeranir is generally verb-initial in independent clauses, and verb-final in dependant clauses, including non-finite clauses using the infinitive, participle, gerund, etc.. These rules may be violated in poetry, however it is much more common to violate the former than the later.

qurra

read-3SG.C

Rāscānus

Rascanus-NOM.SG

salvan

book-ACC.SG

'Rascanus is reading a book'

Rāscānus

Rascanus-NOM.SG

salvan

book-ACC.SG

qurrea

read-SUBJ.3SG.C

'should Rascanus be reading a book...'

sircuīva

tell-PFV.3SG.C

īliō

Ilius-DAT.SG

Rāscānus

Rascanus-NOM.SG

salvan

book-ACC.SG

qurrīhā

read-INF

'Rascanus told Ilius that he was reading a book'

Nominal clitics attach to the end of verbs in independent clauses, and the beginning of verbs in dependant clauses.

taetue

drink-PFV.3SG.E

ne

=2SG

tīn

tea-ACC.SG

'You drank the tea'

tīn

tea-NOM.SG

ni

2SG=

taesun

drink-PFV.PTCP-E.NOM.SG

'The tea you drank'

Word order is much more free for nouns and noun phrases. Adjectives and genitives may either proceed or follow a noun (e.g. formun cōmus or cōmus formun, both 'the warm house;' umae menter or menter umae, both 'my mother's sibling'), although they adjectives generally follow, whilst genitives generally proceed. Prepositions always proceed their noun, whilst postpositions, which are far less common, always follow.

Due to agreement in gender, case, and number between nouns and adjectives, additional nouns may be inserted between a noun and its adjective without changing the meaning, in what is called hyperbaton:

ȳrē

listen-IMP

arte

person-VOC.SG

tihī

1SG.PRO-DAT

iūre

good-T.VOC.SG

'Listen to me good fellow!'

Nouns

Gender

Aeranir nouns are divided into three genders, all of which are directly inherited from late Proto-Maro-Ephenian. These known as the temporary (t), cyclical (c), and eternal (e) genders. The gender of a noun effects the adjectives and verbs that refer to it.

ēs

COP.3SG.T

ars

wumbo(T)-NOM.SG

raius

small-T.NOM.SG

'It's a small wumbo'

sa

COP.3SG.C

tlāna

flower(C)-NOM.SG

raia

small-C.NOM.SG

'It's a small flower'

sī

COP.3SG.E

nātlun

shell(E)-NOM.SG

raiun

small-E.NOM.SG

'It's a small shell'

The gender of most nouns can be easily inferred from its ending. Furthermore, there is often overlap between meaning and gender. Animate living beings and small, breakable objects are often temporary, while abstract concepts, natural processes, or seasonal plants are usually cyclical, and large, durable, inanimate objects are most likely eternal. However, some nouns have no relation to their gender. Personal names are either temporary or cyclical; eternal names are reserved for gods.

Case

Nouns in Aeranir have a series of different forms, called cases of the noun, which have different functions or meanings. For example, the word for 'king' is rēs when subject of a verb, but rēnin when it is the object:

- auhēs rēs 'the king sees (someone)' (nominative case)

- auhēs rēnin '(someone) sees the king' (accusative case)

There are a total of nine cases for most nouns in Aeranir. Outside of the nominative and accusative, they are as the following:

- Vocative: rēne iō!: 'o king!'

- Essive: seū rēnū: 'as this king'

- Instrumental: seōrun rēnerun: 'using this king'

- Genitive: sī rēnis: 'of this king'

- Dative: seō rēnī: 'to/for this king'

- Ablative: seā rēni: 'from/by this king'

- Locative: sīs rēnīs: 'at/with the king'

Sometimes the same endings, e.g. -ī and -ēs, are used for more than one case. Since the function of a word in Aeranir is shown by ending rather than word order, in theory requor rēnī could mean either 'I return to the king' or 'I return from the king.' In practice, however, such ambiguities are rare.

Uses of the cases

Genitive

The use of the genitive case in subordinate clauses has changed throughout the history of Aeranir, and even within the span of time referred to as 'Golden Age Aeranir,' usage was shifting. In Classical and Golden Age Aeranir the genitive could be used with the active voice to mark the subject of the verb, whilst in the middle voice it marked the object. The later is similar to the use of the genitive as a partitive object in Talothic. Some believe this similarity to be the inherited from Proto-Maro-Ephenian, whilst others claim that it is a case of parallel evolution or mutual influence.

tzilla

cat-NOM.SG

artis

person-GEN.SG

auhita

see-PFV.PTCP-C.NOM.SG

'The cat the person saw'

ars

person-NOM.SG

tzillae

cat-GEN.SG

auhitūnus

see-PFV.PTCP-T.NOM.SG

'The person who saw the cat'

The use of genitive objects dwindled in later Golden Age and Late Aeranir, being replaced by the accusative case with the active voice, or the ablative case with the middle voice, as in independent clauses. However, it remained used to mark the subject of dependent clauses, and in Late Aeranir even began to replace the nominative case in independent ones.

Ablative

- Ablative of motion implies movement away from or out of an object:

furuis

fall-PFV-T.3SG

pālā

tree-ABL.SG

'They fell from the tree'

- Agentive ablative marks the agent by whom the action of a passive verb in performed:

īcēlāre

eat-PFV-PASS-E.3SG

pannun

bread-NOM.SG

Traetiā

Traetius-ABL.SG

cnōtun

last-E.NOM.SG

'The last of the bread was eaten by Traetius'

Declensions

Class I

| salva c. book, tome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||||

| word | ending | word | ending | ||

| Primary prīstūmus |

Nominative | salva | -a | salvar | -ar |

| Accusative | salvan | -an | salvae | -ae | |

| Vocative | salva | -a | salvar | -ar | |

| Existential soniāmus |

Essive | salvau | -au | salvur | -ur |

| Instrumental | salvārun | -ārun | salvōs | -ōs | |

| Genitive | salvae | -ae | salvābus | -ābus | |

| Directive satūmus |

Dative | salvō | -ō | salvāna | -āna |

| Ablative | salvā | -ā | salvās | -ās | |

| Locative | salvīs | -īs | salvā | -ā | |

Class II

| pernus t. storm, chaos |

nātlun e. shell, carapace | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | ||||||

| word | ending | word | ending | word | ending | word | ending | ||

| Primary prīstūmus |

Nominative | pernus | -us | pernur | -ur | nātlun | -un | nātlunt | -unt |

| Accusative | pernun | -un | pernī | -ī | |||||

| Vocative | perne | -e | pernur | -ur | |||||

| Existential soniāmus |

Essive | pernū | -ū | pernur | -ur | nātlū | -ū | nātlur | -ur |

| Instrumental | pernōrun | -ōrun | pernōs | -ōs | nātlōrun | -ōrun | nātlōs | -ōs | |

| Genitive | pernī | -ī | pernōvus | -ōvus | nātlī | -ī | nātlōvus | -ōvus | |

| Directive satūmus |

Dative | pernō | -ō | pernōna | -ōna | nātlō | -ō | nātlōna | -ōna |

| Ablative | pernā | -ā | pernōs | -ōs | nātlā | -ā | nātlōs | -ōs | |

| Locative | pernīs | -īs | pernā | -ā | nātlīs | -īs | nātlā | -ā | |

Pronouns

Personal Pronouns

| First person | Second person | Reflexive | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular I |

plural we |

singular you |

plural y'all |

singular/plural himself/herself/ itself/themselves | |||||||||

| full | clitic | full | clitic | full | clitic | full | clitic | full | clitic | ||||

| Primary prīstūmus |

Nominative | aecū | te | eōs | ī | hanae | ne | rōs | er | cē | ce | ||

| Vocative | |||||||||||||

| Accusative | tē | eon | nē | ron | |||||||||

| Existential soniāmus |

Essive | tōs | eor | nōs | rō | cū | |||||||

| Genitive | tī | īster | nī | rester | cī | ||||||||

| Directive satūmus |

Dative | tihī | īvīs | nivī | urvīs | civī | |||||||

| Ablative | tētē | eōvōs | nēnē | rōvōs | cēcē | ||||||||

Third person pronouns

| Singular | Plural | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporary | Cyclical | Eternal | Temporary | Cyclical | Eternal | ||

| Primary prīstūmus |

Nominative | us | va | um | ur | var | ūns |

| Vocative | |||||||

| Accusative | um | vam | vī | vae | |||

| Existential soniāmus |

Essive | ū | vau | ū | ur | vur | ur |

| Instrumental | urun | vārun | urun | vēs | vōs | vēs | |

| Genitive | vis | vae | vis | vus | vāvus | vus | |

| Directive satūmus |

Dative | vī | vō | vī | vina | vāna | vina |

| Ablative | vit | vā | vit | vēs | vās | vēs | |

| Locative | vis | vīs | vis | vā | vā | vā | |

Demonstrative pronouns

Demonstratives underwent a great deal of change during the latest stages of Classical Aeranir, and much of the older forms were preserved in Golden Age Aeranir alongside their newer counterparts. The Classical Aeranir distal and medial demonstratives were formed from the third person pronoun us, va, un plus a suffix. This produced a variety of irregular forms, which were regularised in early Golden Age Aeranir. However, which stem was taken to become the new regular form varied between times, locations, and speakers. Generally, two stems were predominant for each demonstrative; with the medial varying between ust- and unt- and the distal between ūl- and ull-. Eventually, the former of the two became more common, although the latter remained in marginal use, even into the Aeranid languages.

| seus, sea, seun this, this one (proximal) |

ustus, usta, untun that of yours (medial) |

ūlus, ūla, ūllun that, that one (distal) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |||||||||||||

| Temporary | Cyclical | Eternal | Temporary | Cyclical | Eternal | Temporary | Cyclical | Eternal | Temporary | Cyclical | Eternal | Temporary | Cyclical | Eternal | Temporary | Cyclical | Eternal | |

| Nominative | seus | sea | seun | seur | sear | seunt | ustus | usta | untun | urtur | urtar | untunt | ūlus | ūla | ullun | ullur | ullar | ullunt |

| Accusative | seun | sean | sī | seae | untun | untan | vītī | vītae | ullun | ullan | vīlī | vīlae | ||||||

| Vocative | sē | sea | seur | sear | uste | usta | urtur | urtar | ūle | ūla | ullur | ullar | ||||||

| Essive | seū | seau | seū | seur | ūtū | ūtau | ūtū | urtur | ūlū | ūlau | ūlū | ullur | ||||||

| Instrumental | seōrun | seārun | seōrun | seōs | untōrun | untārun | untōrun | vēstōs | ullōrun | ullārun | ullōrun | vēlōs | ||||||

| Genitive | sī | seae | sī | seōvus | seāvus | seōvus | vistī | vistae | vistī | vustōvus | vustāvus | vustōvus | vīlī | vīlae | vīlī | vūlōvus | vūlāvus | vūlōvus |

| Dative | seō | seōna | seāna | seōna | vītō | vintōna | vintāna | vintōna | vīlō | villōna | villāna | villōna | ||||||

| Ablative | seā | seōs | seās | seōs | vistā | vēstōs | vēstās | vēstōs | vīlā | vēlōs | vēlās | vēlōs | ||||||

| Locative | sīs | seā | vistīs | vātā | vīlīs | vālā | ||||||||||||

Even after the new regular demonstratives had been widely adopted, the old ones continued to be used for stylistic purposes, and where considered more proper for official writing, speech, and communication.

In Classical Aeranir, demonstratives could stand for a person or thing, but also a place—there was no distinction between 'this' and 'here.' However, in Golden Age Aeranir, another one of the old stems was generalised to create dedicated locative pronouns vistus, vista, vistun 'there (near you),' and vīlus, vīla, vīlun 'there (far away).' By analogy, the proximal locative demonstrative viseus, visea, viseun 'here' was also created. These were used along side the regular demonstratives to express location.

Possessive pronouns

Possessive pronouns in Aeranir distinguish between many more different types of possession than ordinary nouns, which use only the genitive to mark possession, ownership, association, etc. Pronouns distinguish both alienable and inalienable possession.

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | reflexive | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proximal | distal | medial | |||||||||

| singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | ||

| inalienable | tī te |

īster | nī ne |

rester | sī se |

seōvus | ūlī | ūlōvus | ustī | ustōvus | cī ce |

| alienable | tuius | eius | nuius | ruius | seius | ūleius | usteius | cuius | |||

Objects of inalienable possession are marked with the genitive of a personal or demonstrative pronoun. These include body parts, kinship and familiarity terms, personal attributes, emotions, or thoughts. These pronouns generally proceed the possessee, although that is not always the case, especially in poety. Singular pronouns tī, nī, cī, sī, ustī, and ūlī may be appear as tei, nei, cei, sei, usti, ūli before words starting with a vowel, and te, ne, ce, se, ust, ūl before words starting with i.

se

this-T.GEN.SG

incus

head-NOM.SG

'this one's head'

Alienable possession, including essentially all other categories, is marked via possessive adjectives. These adjective may appear either before or after the possessee, but usually come afterwards. Oftentimes, the different use of alienable/inalienable pronouns may hint at a difference in meaning. The word indus, for example, may mean 'head,' but also 'capital' or 'leader.' With inalienable pronouns, however, it always means 'head,' versus with alienable pronouns, it means 'capital,' or 'leader' because while a head is inalienable, a capital or leader is not. However, this might not always be the case, depending on the possessor and context.

ēs

COP.3SG.T

incus

head-NOM.SG

telūhramir

mesa-ESS.SG=hram-GEN.PL

tuius

mine-T.NOM.SG

'My capital is Telhramir'

ēs

COP.3SG.T

ūlae

that_one's-C.GEN.SG

(tlānae

(flower-GEN.SG

aerānihae)

Aeranid-C.GEN.SG)

incus

head-NOM.SG

telūrhamir

mesa-ESS.SG=rham-GEN.PL

'Its (the Aeranid Empire's) capital is Telrhamir'

Adverbs

Adverbs in Aeranir are used to modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs indicating time, manner, or place. Most adjectives are formed from nouns or adjectives, although they can be derived from some verbs, especially stative verbs. There are a variety of different formulation strategies, depending on the class of the noun/adjective/verb.

- formus ("warm" 1st-2nd declension adjective) → formē ("warmly")

- aerās ("an Aeran" 3rd declension noun) → aerāne ("like an Aeran")

- raelis ("a child" 3rd declension i-stem noun) → raeliter ("like a child")

- vȳlēs ("three days from now" 4th declension noun) → vȳlē ("every three days")

- sacus ("a pin" 5th declension noun) → saciter ("sharply, like a pin")

One of the most notable uses of the adverbial form is with verbs like ficitz ("it makes me"), fitz ("I become"), and caitz ("I change into"). Adverbs can be used to denote the result of a change of state in such a clause.

fīx

make.PFV-3SG.T

prīstus

first-NOM.SG

pāliōne

provincial_governor-ADV

Boezymiae

Boezymia-GEN.SG

'The First Senator made them provincial governor of Boezymia'

sa

COP-3SG.C

Īliō

Ilius-DAT.SG

qūria

power-NOM.SG

tzillē

cat-ADV

cainnī

change_form-GER-GEN

'Ilius has the power to turn into a cat'

Verbs

Conjugation

Agreement

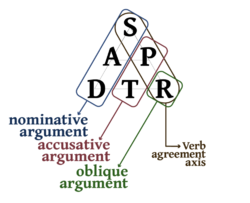

Verbs in Aeranir are conjugated to agree with the number, the person, and in the third person singular, the gender of the most oblique argument given a word's valency, as defined by the DGA pyramid[1]. Here, S represents the subject of an intransitive verb, such as 'the person' in 'the person laughed.' A represents the agent of a transitive verb (also occasually called the subject), or the person or thing that does the action of the verb, such as 'the child' in 'the child reads the book.' D marks the donor, a special type of agent, who gives something or does a the action of a verb for the benefit of another, such as ‘the senator’ in ‘the senator gave the cat some milk.’ These are collectively called the nominative argument, and are expressed usually with the nominative case, but also occasionally with the genitive case in dependant clauses.

P represents the patient of a transitive verb, or the person or thing towhich the verb is done, also called the direct object, such as ‘the book’ in ‘the child reads the book.’ T represents the theme, or the object that is given to someone or something, such as ‘the milk’ in ‘the senator gave the cat some milk.’ These two roles make up the accusative argument, which is marked with the accusative case. Finally, R represents the recipient, or the person who recieves the theme from the donor, or benefits from the donor's action, with a ditransitive verb, also commonly called the indirect object, such as 'the cat' in 'the senator gave the cate some milk.'

Aeranir verbs conjugate their endings to agree with the most oblique argument in a clause. That means the subject of an intransitive verb (e.g. clautitz; 'I laugh'), the patient of a transitive verb (e.g. auhente; 'I look at you'), or the recipient of a ditransitive verb (e.g. tzavī'r salvae; 'you all gave me the books').

mollī

leak-3SG.E

cōmus

house-NOM.SG

'The house is leaking'

requis

return-3SG.C

te

=1SG

coptin

hat-ACC.SG

nuiun

2SG.POS.PRO-T.ACC.SG

'I'm giving back your hat'

imptās

send-POT.3SG.T

ne

=2SG

mu

=INTERR

sōlī

clothing-ACC.PL

nomī

new-IPFV.PTCP-T.ACC.SG

Sētīlī

Setil-DAT.SG

'Can you send Setil the new clothes?'

It should be noted that a verb in the active voice must always have the maximum number of arguments according to its inherent transitivity. This means, for example, that one can never say 'John eats.' Because 'to eat' is transitive, there must be a patient, or direct object, e.g. 'John eats food.' However, there are a number of valancy dropping operations available in Aeranir to allow various arguments to be dropped, which are discussed in the section on voice.

Additional arguments can be expressed with pronominal clitics attached to the end of a verb in independant clauses and to the beginning in dependant ones (e.g.auhente; 'I look at you,' tzāvī'r salvae; 'you all gave me the books'), however these are not considered part of a verbs conjugation, and are optional, especially if the information can be assumed or is known between speakers.

Number of Conjugations

| Aspect → | Imperfective | Perfective | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood → Voice ↓ |

Indicative | Subjunctive | Desiderative | Potential | Indicative | Subjunctive | Desiderative | Potential |

| Active | aehatz They love me |

aehet They should love me |

aehārit They want to love me |

aehātatz They can love me |

aehāvī They loved me |

aehēvī They should have loved me |

aehāruī They wanted to love me |

aehātāvī They could have loved me |

| Middle | aehor I love |

aeheō I should love |

aehārō I want to love |

aehātor I can love |

aehāvō I loved |

aehēvō I should have loved |

aehāruō I wanted to love |

aehātāvō I could have loved |

| Passive | aehālō I am loved |

aehēlō I should be loved |

aehārēlō I want to be loved |

aehātālō I can be loved |

aehāvēlō I was loved |

aehēvēlō I should have been loved |

aehāruēlō I wanted to be loved |

aehātāvēlō I could have been loved |

| Causative | aehātitz They let me love them |

aehātiat They should let me love them |

aehātīrit They want to let me love them |

aehāssītatz They can let me love them |

aehātīvī They have let me love them |

aehātiāvī They should have let me love them |

aehātīruī They wanted to let me love them |

aehāssītāvī They could have let me love them |

Conjugation formation

| ipfv | A-grade | I-grade | E-grade | Null-grade | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strong | weak | strong | weak | strong | weak | strong | weak | ||

| act | ind | root-ā-act.ipfv | root-ī-act.ipfv | root-ē-act.ipfv | root-act.ipfv | ||||

| subj | root-ē-act.ipfv | root-iā-act.ipfv | root-eā-act.ipfv | root-ē-act.ipfv | |||||

| des | root-s-act.ipfv | root-ār-act.ipfv | root-s-act.ipfv | root-er/īr-act.ipfv | root-s-act.ipfv | root-er/īr-act.ipfv | root-s-act.ipfv | root-er-act.ipfv | |

| pot | root-tā-act.ipfv | root-ātā-act.ipfv | root-tā-act.ipfv | root-itā/ītā-act.ipfv | root-tā-act.ipfv | root-itā/ītā-act.ipfv | root-tā-act.ipfv | root-itā-act.ipfv | |

| mid | ind | root-ā-mid.ipfv | root-ī-mid.ipfv | root-ē-mid.ipfv | root-mid.ipfv | ||||

| subj | root-ē-mid.ipfv | root-iā-mid.ipfv | root-eā-mid.ipfv | root-ē-mid.ipfv | |||||

| des | root-s-mid.ipfv | root-ār-mid.ipfv | root-s-mid.ipfv | root-er/īr-mid.ipfv | root-s-mid.ipfv | root-er/īr-mid.ipfv | root-s-mid.ipfv | root-er-mid.ipfv | |

| pot | root-tā-mid.ipfv | root-ātā-mid.ipfv | root-tā-mid.ipfv | root-itā/ītā-mid.ipfv | root-tā-mid.ipfv | root-itā/ītā-mid.ipfv | root-tā-mid.ipfv | root-itā-mid.ipfv | |

| pas | ind | root-ā-pas.ipfv | root-ī-pas.ipfv | root-ē-pas.ipfv | root-pas.ipfv | ||||

| subj | root-ē-pas.ipfv | root-iā-pas.ipfv | root-eā-pas.ipfv | root-ā-pas.ipfv | |||||

| des | root-s-pas.ipfv | root-ār-pas.ipfv | root-s-pas.ipfv | root-er/īr-pas.ipfv | root-s-pas.ipfv | root-er/īr-pas.ipfv | root-s-pas.ipfv | root-er-pas.ipfv | |

| pot | root-tā-pas.ipfv | root-ātā-pas.ipfv | root-tā-pas.ipfv | root-itā/ītā-pas.ipfv | root-tā-pas.ipfv | root-itā/ītā-pas.ipfv | root-tā-pas.ipfv | root-itā-pas.ipfv | |

| caus | ind | root-tī-act.ipfv | root-ātī-act.ipfv | root-tī-act.ipfv | root-itī/ītī-act.ipfv | root-tī-act.ipfv | root-itī/ītī-act.ipfv | root-tī-act.ipfv | root-itī-act.ipfv |

| subj | root-tiā-act.ipfv | root-ātiā-act.ipfv | root-tiā-act.ipfv | root-itiā/ītiā-act.ipfv | root-tiā-act.ipfv | root-itiā/itiā-act.ipfv | root-tiā-act.ipfv | root-itiā-act.ipfv | |

| des | root-tier-act.ipfv | root-ātier-act.ipfv | root-tier-act.ipfv | root-itier/ītier-act.ipfv | root-tier-act.ipfv | root-itier/ītier-act.ipfv | root-tier-act.ipfv | root-itier-act.ipfv | |

| pot | root-sītā-act.ipfv | root-āsītā-act.ipfv | root-sītā-act.ipfv | root-issītā/īsītā-act.ipfv | root-sītā-act.ipfv | root-issītā/īsītā-act.ipfv | root-sītā-act.ipfv | root-issītā-act.ipfv | |

| pfv | A-grade | I-grade | E-grade | Null-grade | |||||

| strong | weak | strong | weak | strong | weak | strong | weak | ||

| act | ind | root-act.pfv | root-u/āv-act.pfv | root-act.pfv | root-u/īv-act.pfv | root-act.pfv | root-u/ēv-act.pfv | root-act.pfv | root-u-act.pfv |

| subj | root-ē-act.pfv | root-uē/ēv-act.pfv | root-ē-act.ipfv | root-uē/iāv-act.pfv | root-ē-act.pfv | root-uē/eāv-act.pfv | root-ē-act.pfv | root-uē-act.pfv | |

| des | root-su-act.pfv | root-āru-act.pfv | root-su-act.pfv | root-eru/īru-act.pfv | root-s-act.pfv | root-eru/īru-act.pfv | root-su-act.pfv | root-eru-act.pfv | |

| pot | root-tāv-act.pfv | root-ātāv-act.pfv | root-tāv-act.pfv | root-itāv/ītāv-act.pfv | root-tāv-act.pfv | root-itāv/ītāv-act.pfv | root-tāv-act.pfv | root-itāv-act.pfv | |

| mid | ind | root-mid.pfv | root-u/āv-mid.pfv | root-mid.pfv | root-u/īv-mid.pfv | root-mid.pfv | root-u/ēv-mid.pfv | root-mid.pfv | root-u-mid.pfv |

| subj | root-ē-mid.pfv | root-uē/ēv-mid.pfv | root-ē-mid.pfv | root-uē/iā-mid.pfv | root-ē-mid.pfv | root-uē/eā-mid.pfv | root-ē-mid.pfv | root-uē-mid.pfv | |

| des | root-su-mid.pfv | root-āru-mid.pfv | root-su-mid.pfv | root-eru/īru-mid.pfv | root-su-mid.pfv | root-eru/īru-mid.pfv | root-su-mid.pfv | root-eru-mid.pfv | |

| pot | root-tāv-mid.pfv | root-ātāv-mid.pfv | root-tāv-mid.pfv | root-itāv/ītāv-mid.pfv | root-tāv-mid.pfv | root-itāv/ītāv-mid.pfv | root-tāv-mid.pfv | root-itāv-mid.pfv | |

| pas | ind | root-pas.pfv | root-u/āv-pas.pfv | root-pas.pfv | root-u/īv-pas.pfv | root-pas.pfv | root-u/ēv-pas.pfv | root-pas.pfv | root-u-pas.pfv |

| subj | root-pas.pfv | root-uē/ēv-pas.pfv | root-pas.pfv | root-uē/iāv-pas.pfv | root-pas.pfv | root-uē/eā-pas.pfv | root-pas.pfv | root-uē-pas.pfv | |

| des | root-su-pas.pfv | root-āru-pas.pfv | root-su-pas.pfv | root-eru/īru-pas.pfv | root-su-pas.pfv | root-eru/īru-pas.pfv | root-su-pas.pfv | root-eru-pas.pfv | |

| pot | root-tāv-pas.pfv | root-ātāv-pas.pfv | root-tāv-pas.pfv | root-itāv/ītāv-pas.pfv | root-tāv-pas.pfv | root-itāv/ītāv-pas.pfv | root-tāv-pas.pfv | root-itāv-pas.pfv | |

| caus | ind | root-tīv-act.pfv | root-ātīv-act.pfv | root-tīv-act.pfv | root-itīv/ītīv-act.pfv | root-tīv-act.pfv | root-itīv/ītīv-act.pfv | root-tīv-act.pfv | root-itīv-act.pfv |

| subj | root-tiāv-act.pfv | root-ātiāv-act.pfv | root-tiāv-act.pfv | root-itiāv/ītiāv-act.pfv | root-tiāv-act.pfv | root-itiāv/itiāv-act.pfv | root-tiāv-act.pfv | root-itiāv-act.pfv | |

| des | root-tieru-act.pfv | root-ātieru-act.pfv | root-tieru-act.pfv | root-itieru/ītieru-act.pfv | root-tieru-act.pfv | root-itieru/ītieru-act.pfv | root-tieru-act.pfv | root-itieru-act.pfv | |

| pot | root-sītāv-act.pfv | root-āsītāv-act.pfv | root-sītāv-act.pfv | root-issītāv/īsītāv-act.pfv | root-sītāv-act.pfv | root-issītāv/īsītāv-act.pfv | root-sītāv-act.pfv | root-issītāv-act.pfv | |

Principle Parts

The verb in Aeranir is primarily made of three parts: root, theme, and ending, with an optional forth category, the suffix, for forming the perfective. The root and theme combine to form the stem. The root carries the semantic content of the word, and can also be conjugated to carry modal imformation. The theme describes how the stem interacts with the ending, and can also be changed, along with the stem and endings, to express a variety of different grammatical meanings. Endings indicate the voice, aspect, person, number, and gender of the most oblique argument in the DGA scheme.

| Active | Middle | Passive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperfective | Perfective | Imperfective | Perfective | Imperfective | Perfective | |||

| Singular | 1st Person | -itz/-it | -ī | -or/-ō | -ō | -ēlō | -ēlō | |

| 2nd Person | -in | -in | -istī | -ist | -ēlāstī | -ēlast | ||

| 3rd Person | temporary | -is | -is | -erur | -ere | -ēlārur | -ēlāre | |

| cyclical | -a | -a | -era | -ēlāra | ||||

| eternal | -ī | -e | -erur | -ēlārur | ||||

| Plural | 1st Person | -imus | -ime | -imur | -imur | -ēlāmur | -ēlāme | |

| 2nd Person | -itis | -ite | -itur | -itur | -ēlātur | -ēlāte | ||

| 3rd Person | -intz/-int | -int | -intur | -intur | -ēlantur | -ēlante | ||

The way in which a verb will conjugate can be determined from how it forms the following five constructions:

- the active idicative imperfective first person singular

- the active imperfective accusative infinitive

- the active perfective participle

- the active desiderative imperfective first person singular

- the active indicative perfective first person singular

These five forms are refered to as a verb's reference forms. They are often shortend to first person singular (1p.sg), accusative infinitive (acc.inf), perfective participle (pfv.ptcp), desiderative first person singular (des.1p.sg), and perfective first person singular (pfv.1p.sg) respectively.

The first two of these reference forms determines a verb's base theme vowel, or what vowel is used in its indicative imperfective forms. There are four main thematic classes; one weak or null class, wherein the ending is applied directly to the stem, and three strong classes, wherein a thematic vowel is inserted between the stem and the ending.

| t-stem | s-stem | |

|---|---|---|

| -m- | → -mpt- | → -s-* |

| -n- | → -nt- | |

| -ñ- | → -ñct- | |

| -p- | → -pt- | → -ps- |

| -t- | → -ss- → -s-** |

→ -ss- → -s-** |

| -tl- | ||

| -tz- | ||

| -c- | → -ct- | → -x- |

| -cu- | ||

| -q- | → -qt- | → -qs- |

| -qu- | ||

| -s- | → -st- | → -ss- → -s-** |

| -r- | → -st- → -s-** → -rt-†† |

→ -ss- → -s-** → -rr-†† |

| -l- | → -s-** → -lt-†† |

→ -s-** → -ll-†† |

| -v- | → -ut-‡ → -ct-*†† → -qt-*†† |

→ -ur-‡ → -x-*†† → -qs-*†† |

| -i- | → -ct-* → -qt-*†† |

→ -x-* → -qs-*†† |

| -h- | ||

| -V- | → -Vt- | → -Vr- |

| Ending | Theme | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| -ā- | -ē- | -ī- | |

| -itz | → -atz | → -etz | → -itz |

| -is | → -ās | → -ēs | → -īs |

| -a | → -a | → -ea | → -ia |

| -ī | → -ae | → -ī | → -ī |

| -imus | → -āmus | → -ēmus | → -īmus |

| -or | → -or | → -eor | → -ior |

| -ēlō | → -ālō | → -ēlō | → -iēlō |

The second two determine a verb's t-stem and s-stem. These stem alterations are used for further conjugation, the t-stem forming the active and middle perfective participles, the causative voice, and the potential mood, and the s-stem forming the desiderative. The t- and s-forms often are identical, however meaning is useally further differentiated by thematic vowels, so completely identical forms are rare.

The final form determines how a verb with form the perfective aspect. Generally, there are three main strategies for this: the application of suffix -u- directly after the stem (e.g. oelitz ("I work") → oeluī ("I worked")), the appication of the suffix -v- after a theme vowel (e.g. aehatz ("they love me") → aehāvī ("they loved me")), or no suffix, with lengthening of the root vowel (e.g. lecitz ("I choose") → lēcī ("I chose")). It should be noted that the perfective is always followed by weak endings.

Occassionally, a thematic vowel, weak or strong, may be inserted before the t- or s-stem. This is most common in verbs with a base thematic -ā-, which often functions as a part of the stem (e.g. aehatz → aehātus ("that loved") aehārit ("they want to love me") vs. mavatz ("I wander") → mautus ("that wandered") maurit ("I want to wander)). This may occur with other theme classes, although it should be noted that -ē- is never used, and is always replaced with -ī-.

Aspect

Aeranir verbs have two basic aspects, which express how the verb extends over time. Aspect differs from tense in that it deals with the completion or continuity of an action or state, rather than the absolute timeframe inwhich it took place. Each aspect may be in any voice and/or mood. Aspect is expressed primarily through endings, and secondarily through the suffix, as discussed above.

Imperfective

The imperfective aspect describes a situation viewed with interior composition. It describes ongoing, habitual, or repeated situations, rather or not they occured in the past, present, or future. The imperfective aspect is considered the most basic, unmarked aspect of a verb. The stem is uninflected, and endings are attached directly to the verb's basic theme vowel.

Pefective

The perfective aspect in Aeranir describes situations viewed with exterior composition, which is to say actions which are completed and viewed as a unified whole, whether thet take place in the past present, or future, although this construction is very rarely used in for the future.

There are a variety of different strategies to form the perfective. Many of them involve the suffix, which takes the form of -v- between vowels and -u- after consonants. All of them take the perfective endings.

- Attachment of the suffix directly to the stem.

- Attachment of the suffix after base thematic vowel.

- No suffix; perfective endings attached directly to the stem, with root vowel lengthening.

Mood

Indicative

The indicative mood is the baseline grammatical mood in Aeranir. It is used in declarative statements, to express statements or facts, of what the speaker considers true or known. It is the least marked mood of a verb, taking endings directly to the base theme vowel, stem, or suffix.

Subjunctive

The subjunctive mood (subj) has numerous, but genreally speaking is used to express such nuances as 'would,' 'should,' or 'may.' It can be used to refer to information that the speaker is unsure about, such as hearsay, or for theoretical or hypotherical situations. It is often found in subordinate clauses, annd may be used for conditional statements (e.g. if..., when...).

| Type | Change | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Verbs | -ø- → -ē- | meñitz → meñet | |

| -ē- → -ā- | meñēlō → meñālō | ||

| Strong Verbs |

a-stem | -ā- → -ē- | aehatz → aehet aehālō → aehēlō |

| i-stem | -ī- → -iā- | sēpitz → sēpiat | |

| -iē- → -iā- | sēpiēlō → sēpiālō | ||

| e-stem | -ē- → -eā- | cōretz → cōreat cōrēlō → cōreālō | |

Forming the subjunctive

The subjunctive is formed by shifting a verb's base theme vowel, as described by the table to the left. This shift happens after the stem, but may be either before or after the suffix, depending on whether or not there is a theme vowel before the suffix in the indicative. So the perfective of aehēs ("they should love it") is aehēvis (from indicative aehāvis) but sēpiās ("they should cut it") is sēpuēs (from indicative sēpuis), not **aehāvēs or **sēpēvis. Although these forms are occasionally found in non-standard writing, they are considered incorrect my grammaticians.

The imperfective subjunctive uses the 1st person sungular -it instead of -itz, and -ō instead of -or: pacitz, pacior ("they take me, I take") become paciat, paciō ("they should take me, I should take").

The 1st person subjunctive perfective in verbs that have no theme vowel before the suffix and does not extend the root vowel is identical to the indicative, and the mood must be inferred through conext: saepuī may be either "they cut me" or "They should cut me." The 3rd person active cyclical singulars in verbs with base theme vowels -ī- and -ē- are also identical, e.g. both pacia ("they take it/they should take it"), auhea ("they see it/they should see it").

Uses of the subjunctive

The subjunctive has numerous uses, ranging from what potentially might be true to what the speaker wishes or commands should happen. It is often translated with 'should', 'could', 'would', 'may' and so on, but in certain contexts it is translated as if it were an ordinary indicative verb.

One use of the subjunctive is the speculative subjunction, used when the speaker imagines what potentially may, might, would, or could happen in the present or future or might have happened in the past. Negation for this type uses mū.

auheārur

see-MID.SUBJ.3SG.E

seun

this-E.NOM.SG

oeliun

job-NOM.SG

stērē

hard-ADV

'This job seems difficult'

moeiea

please-SUBJ.3SG.C

Osculan

Little.Oscus-ACC.SG

tzānū

gift-ESS.SG

salva

book-NOM.SG

'Little Oscus may like a book as a gift'

The subjunctive may also be used as the optative subjunctive, expressing what the speaker wishes may happen, or wishes had happened. These expresses a weaker or more generalised desire, as opposed to the desiderative mood. Negation for this type uses mū.

ciāvis

come-PFV.SUBJ.3SG.T

mū

NEG

seus

this-T.NOM.SG

incerī

capital-DAT.SG

pernus

storm-NOM.SG

'If only this storm hadn't come to the capital!'

The jussive subjunctive can be used for commands or suggestions for what should happen. It is less direct and far more common than the imperative. Negation for this type uses mīm.

ven

go-SUBJ.2SG

hānō

temple-DAT.SG

ē

against

vecō

curse-DAT.SG

veniennō

win-GER-DAT

'You should go to the temple to prevail against the curse'

Perhaps the most common use of the subjunctive is the conditional subjunctive. When the subjunctive is used in a subordinate clause (with the verb moving to the final position), it may carry the meaning 'if, when, should, etc..' This can be used both in finite verb forms, and with participles, the former being more popular in Old inscriptions and the later in Classical ones. Negation for this type uses mīm.

Desiderative

The desiderative is used primarily to express wants or desires. While the subjunctive may be used for this as well (see optative subjunctive), the desiderative is considered less abstract or wishful, signalling concrete and actionable wants. It is formed from the s-stem of a verb, with no theme vowel between it and the ending, and using the secondary first person singular and third person plural markers (e.g. -it and -end vs. primary -itz and -entz). Verbs generally follow three patterns to form the s-stem;

- -s- is appended to the root, causing no other alteration to the root.

- -s- is appended after a theme vowel, causing -s- to become -r-.

- -s- is appended to the root, causing some alteration to the root, and perhaps the -s- augment as well.

Potential

The potential mood indicates that, in the opinion of the speaker, one has the ability or capability to do something. It should not be confused with the subjunctive mood, which may be used to express that something is likely or possible to occur. The potential always deals with ability. It may be formed from the t-stem of a verb, plus the thematic vowel -a- (as opposed to the causative voice, which is formed with the t-stem plus the thematic vowel -i-). Like the desiderative, there are three main paradigms by which the t-stem of a verb is formed;

- -t- is appended to the root, causing no other alteration to the root.

- -t- is appended after a theme vowel.

- -t- is appended to the root, causing some alteration to the root, and perhaps the -t- augment as well.

It should be noted that in the causative voice of the potential mood, the first -t- augment often dissimilates to -s/ss-;

- auhititz ("they let me look at it") → **auhitītatz → auhissītatz ("they can let me look at it")

- reqtitz ("they let me return it") → **reqtītatz → reqsītatz ("they can let me return it")

Voice

Active

Middle

The middle voice (also called the mediopassive voice) is in the middle between the active and the passive voices, as the subject often cannot be categorised as either agent or patient but may have elements of both. The middle voice is usually inherently intransitive, and transitive or ditransitive verbs conjugated into the middle voice usually become intransitive themselves. It is formed by attaching the middle verb endings to the root of a verb.

The meaning of a verb in the middle voice often depends on the context of the sentence and the lexical properties of the word itself. In its most basic sense, it may be used simply as a valancy decreasing operation. As transitive verbs require an object in the active voice (because transitive verbs must agree with the object), the middle voice may be used merely to omit an object, to highlight the subject or some other part of the sentence, or to simply make a blanket statement.

- aehatz 'they love me' (active) → aehor 'I love' (middle)

- lecis 'theyi choose themj' (active) → lecerur 'theyj choose' (middle)

Animacy can play a major role in the meaning of a verb in the middle voice. Verbs with more animate subjects, such as people, animals, gods, etc., may be interpreted as more towards an active meaning, whilst less animate subjects, like inanimate objects or possessions, may be interpreted as more passive in meaning.

auhērur

see-MID.3SG.T

seus

this-T.NOM.SG

ars

wumbo-NOM.SG

(more animate)

'That wumbo sees'

auhēra

see-MID.3SG.C

sea

this-C.NOM.SG

salva

book-NOM.SG

(less animate)

'That book is seen'

Sometimes, it may have a reflexive meaning, or the sense of doing something for ones own benefit.

vascit

wash-ACT.1SG

vominis

river-LOC.SG

(active voice)

'They wash me in a river'

vascor

wash-MID.1SG

vominis

river-LOC.SG

(middle voice)

'I washed (myself) in a river'

hastās

sacrifice-ACT.3SG.T

Oscus

Oscus-NOM.SG

aprun

fish-ACC.SG

(active voice)

'Oscus sacrificed a fish'

hastārur

sacrifice-MID.3SG.T

Oscus

Oscus-NOM.SG

aprōrun

fish-INSTR.SG

(middle voice)

'Oscus sacrificed a fish (for their benefit)'

Another important use of the middle voice is the experiential middle voice. When used with sensory verbs the middle voice may be used to differentiate experiential, nonvolitional sensation (see, hear, smell, feel, know, etc.), as opposed to active, volitional sensation (look, listen, sniff, touch, understand, etc.) Often times, the object of the sensory verb will be expressed using an oblique case, usually the ablative.

ȳrēs

hear/listen-ACT.3SG.T

te

=1SG.NOM

ponun

voice-ACC.SG

carīnī

friend-GEN.SG

hellē

happily

(active voice)

'I like to listen to (my) friend's voice'

ȳreor

hear/listen-MID.1SG

ponā

voice-ABL.SG

carīnī

friend-GEN.SG

hellē

happily

(middle voice)

'I like to hear (my) friend's voice'

The middle voice may also be used with a variety of verbal compliments—usually adverbs—which describe the quality of the subject, or the result of the action. Often times such constructions may be expressed in English as adjective to verb, e.g. 'easy to love'.

qurrera

read-MID.3SG.C

salva

book-NOM.SG

hēs

matters-NOM.SG

collēcta

gather-PFV.PTCP-C.NOM.SG

aplīdiāna

of_Avrid-C.NOM.SG

iūs

well

'The book "Collected Matters of Avrid" is a good read' (lit. '~reads well')

taetuere

drink-PFV.MID.3SG.E

tīn

tea-NOM.SG

īvīs

1PL.PRO-DAT

lȳrīs

time-LOC.SG

saltīs

pass-PFV.PTCP-T.LOC.SG

ni

2SG=

fictun

make-PFV.PTCP-E.NOM.SG

satun

pour-PFV.PTCP-E.NOM.SG

iūs

well

'The tea you made us last time was delicious' (lit. '~drank well')

Passive

The passive voice in Aeranir shares many traits with the middle voice, and often times the distinction between the two can be subtle, nuanced, or obscure. The passive was rare in Old Aeranir and even in the Classical period remained unusual, with the middle voice still preferred for passive clauses. It only began to rise in popularity in Late Aeranir. In its most basic form, the grammatical subject (nominative argument) expresses the theme or patient of the main verb – that is, the person or thing that undergoes the action or has its state changed. This is opposed to the active voice, where the nominative argument expresses the agent of a transitive clause or subject of an intransitive one, and the middle voice, which has traits of both.

Uses of the passive

Unlike the middle voice, the passive is not used for verbal complements, and it cannot take the agent of a verb as its subject. It is never used in verbal complements.

taeterur

drink-MID.3SG.E

seun

this-E.NOM.SG

tīn

tea-NOM.SG

iūs

well

'This tea tastes good' (lit. 'it drinks well')

taetēlārur

drink-PAS.3SG.E

seun

this-E.NOM.SG

tīn

tea-NOM.SG

iūs

well

'This tea is drunk often'

While the agent may be dropped in a passive clause, it may also be included, using the ablative case.

praestrōcuēlāre

rebuild-PFV.PAS.3SG.E

ūlun

yonder-E.NOM.SG

Cavā

Cava-ABL.SG

Īliānā

Ilianus-C.ABL.SG

hānun

temple-NOM.SG

'This temple was rebuilt by Cava Iliana'

The passive can also be especially with intransitive verbs to form denote an unspecified/generic subject. This structure may is used to make general statements or observations. Negation for this type uses mū.

miquientur

die-MID.3PL.T

'They are dead/dying.'

miquiēlantur

die-PAS.3PL.T

'There are people dead/dying'

mūhera

not.enough-MID.3SG.C

(sea)

(this-C.NOM.SG)

artina

wumbo-DAT.PL

inceris

capital-GEN.SG

alta

water-NOM.SG

'This is not enough water for the people of the capital'

mūhēlāra

not.enough-PAS.3SG.C

artina

wumbo-DAT.PL

inceris

capital-GEN.SG

alta

water-NOM.SG

'There is not enough water for the people of the capital'

Similarly, the passive can be used to form the aversive passive, denoting an undesirable event or outcome. The affecting action may happen directly to the subject, or to another person or thing.

cōmerī

home-DAT

requintus

return-IPFV.PTCP-T.NOM.SG

furuēlō

fall-PFV.PAS.1SG

sopere

snow-ABL.SG

'Walking home I got snowed on'

miquīvēlast

die-PFV-PAS.2SG

apiesterā

master-ABL.SG

'Your master has died on you' (i.e., died and it negatively affects you)

In some uses of the aversive passive, the subject of the sentence may be difficult to ascertain. For example, the sentence furuī pālā 'I fell from the tree' can be expressed in using the aversive passive, because the action is undesirable. However, the straight aversive passive, furuēlō pālā, is ambiguous; it could mean either 'I fell from the tree' (using the ablative of motion) or 'The tree fell on me' (using the agentive ablative).

In the first interpretation, the first person argument is the semantic subject of the clause, whilst in the second it is the tree. In order to emphasise that the semantic subject and syntactic arguments are the same (i.e. it is I who fell from the tree), the reflexive pronoun cē may be used; e.g. furuī pālā ('I fell from the tree') → furuēlō cē pālā ('I fell from the tree, and it negatively affected me' lit. 'I fell myself from the tree').

Causative

Non-finite forms

The infinitive

| Imperfective | Perfective | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| accusative | oblique | meaning | accusative | oblique | meaning | |

| Active | aehāhā -hā |

aehāri -ri |

to love (someone) |

aehāhī -hī |

aehārī -rī |

to have loved (someone) |

| Middle | aehāssi -ssi |

aehāiēs -iēs |

to love | aehāssī -ssī |

aehāiērī -iērī |

to have loved |

| Passive | aehātus sinhā PFV.PTCP + sinhā |

aehātus fiēs PFV.PTCP + fiēs |

to be loved | aehātus fūhī PFV.PTCP + fūhī |

aehātus fiērī PFV.PTCP + fiērī |

to have been loved |

| Causative | aehātīhā -tīhā |

aehātīri -tīri |

to make (someone) love (someone) |

aehātīhī -tīhī |

aehātīrī -tīrī |

to have made (someone) love (someone) |

The infinitive in Aeranir is a special verbal form used to form complement clauses.

Uses of the infinitive

The infinitive in Aeranir can be used to report indirect speech, hearsay, speculation, or sensation.

pēra

pass-PFV.3SG.C

tihī

1SG.PRO-DAT

incerī

capital-DAT.SG

ni

2SG=

cīhī

come-PFV.INF

'They told me that you'd come to the capital'

ȳrēva

hear-PFV.3SG.C

te

=1SG

Mussā

Mussa-ABL.SG

Limī

Limius-GEN.SG

carīnōvus

friend-GEN.PL

quo

=and

neme

newly

cōmus

home-ACC.SG

strōcēhā

build-INF

'I heard from Mussa that Limius and their friends are building a new house'

The gerund

The gerund in Aeranir is a infinite verb form which displays characteristics of both a noun and a verb. It declines for a limited scope of cases (although not for gender nor number), but can take object and adjunct arguments like a verb. It usually has an adverbial/adjectival meaning, and never agrees with the main verb.

Forming the gerund

- Null-grade verbs: root-innū; e.g. taetihan ('to drink') → taetinnū ('whilst drinking').

- A-grade verbs: root-annū; e.g. iuvāhan ('to write') → iuvannū ('whilst writing').

- I-grade verbs: root-iennū; e.g. cītīhan ('to cut') → cītiennū ('whilst cutting').

- E-grade verbs: root-ennū; e.g. aquēhan ('to be open') → aquennū ('whilst open').

Uses of the gerund

The meaning of the gerund changes depending on its case. The essive and locative can be used to indicate temporal action in relation to the main action of a sentence. The essive indicates simultaneous action, i.e. two actions that cooccur. This may be relayed in English via the conjunction 'whilst.'

murran

wall-ACC.SG

travannū

walk-GER.ESS

pērintur

converse.PFV-MID.3PL

pāliō

governor-NOM.SG

mater

senator-NOM.SG

'Whilst they walked along the wall, the governor and senator conversed'

This overlaps with certain uses of the imperfective participle (see § uses of the participle), e.g. murran travantur pērintur pāliō mater is synonymous with the above example. In contrast, the locative gerund is used to show actions beginning at the same time. This may be relayed with English 'when' or 'as.'

pāsillan

fireword-ACC.SG

cītiennīs

cut-GER.LOC

auhēva

see-PFV-C.3SG

sartī

knife-GEN.SG

tūī

mine-T.GEN.SG

cōrēssī

break-PFV.MID.ACC.INF

'As I (began to) cut the firewood, I saw that my knife was broken'

This differs from usage of the perfective participle, which signals the main action starting at the end of the dependant one, i.e. pāsillan cīsus auhēva sartī tūī cōrēssī 'having cut the firewood I saw that my knife was broken.'

In addition, the essive gerund may be used with the verb rēhan ('to do') in order to express an attempt, goal, or aim. In the perfective aspect, this is usually interpreted as a failed attempt.

rēvō

do-PFV-MID.1SG

salvan

book-ACC.SG

ā

over

vitlās

life-ABL.PL

Īliānōvus

Ilian-GEN.PL

iuvannū

write-GER.ESS

'I tried (but failed) to write a book about the lives of the Ilians.'

The genitive and dative cases of the gerund are used to express aim, goal, or purpose. The genitive gerund marks the purpose or use of a noun, whilst the dative gerund marks the purpose of a verb or action.

pea

grow-C.3SG

cūran

herb-ACC.SG

vecunt

illness-ACC.PL

inceris

head-GEN.SG

moñennī

heal-GER.GEN

'They grow an herb for healing illnesses of the head'

serue

order-PFV.E.3SG

te

=1SG

Caescārin

Caescar-ACC.SG

mumae

mother-ACC.PL

ūī

their-T.ACC.PL

sihinnō

sate-GER.DAT

pāliōna

post-DAT.PL

'I ordered Caescar to the boarder to appease their parents'

Furthermore, the dative gerund may be used with the middle voice of the verb rēhan ('to do') in a similar way to the essive, however in this case denoting intent, plans, will, or conjecture.

reor

do-MID.1SG

cartō

dance-DAT.SG

cur

with

Mussiō

Mussius-DAT.SG

vannō

go-GER-DAT

'I intend to go to the dance with Mussius'

reāvere

do-MID.SUBJ.PFV-3SG

seō

this-DAT.SG

scericca

undertaker-NOM.SG

ciennō

come-GER-DAT

'The undertaker should have come here (they planned to do so)'

The ablative and instrumental cases of the gerund can be used to express cause, i.e. 'by doing x,' or 'because x.' The ablative generally marks unintentional or natural causes, whilst the instrumental marks intentional cause.

tlānae

flower-ACC.PL

ustae

that(medial)-C.ACC.PL

quo

=and

peannā

plant-GER-ABL

rēve

do-PFV-E.3SG

cōmus

house-ACC.SG

pūterē

beautiful-ADV

'By planting all these flowers you've made the house beautiful'

ustam

that(medial)-C.ACC.SG

prī

before

tētē

1SG-ABL

harēnam

paper-ACC.SG

matrī

senator-DAT.SG

iminnōrun

send-GER-INSTR

restērāvist

assure-PFV-MID.2SG

pāliōnū

governor-ESS.SG

gaeticae

Gaetica-GEN.SG

'By sending the senator that letter before me, you've assured your place as governor of Gaetica'

Semantics

Temporal expressions

The ancient Aerans divided the day from noon to noon into one hundred lammar (sg. lamma) of equal length, roughly 14.4 minutes long. The daytime was divided into sixteen lȳrar (sg. lȳra), and night into four or five volar (sg. vola) depending on the season. Time was kept on a device called a lammāriun, a type of clock. Early lammāriunt only measured lammar, and one had to consult an almanac (lȳrāriun) to determine the length and starting time of each lȳra or vola on a given day.

The verb spurhan ('to hang (trans.)') is used to denote spending or taking time;

spurra

hang-MID.C.3SG

sau

only

īma

one-C.NOM.SG

lamma

lamma-NOM.SG

āmātiō

market-DAT.SG

vannō

go-GER-DAT

'It only takes one lamma to get to the market'

qurrintus

read-PTCP-T.NOM.SG

spūrint

hang.PFV-3PL

te

=1SG

volae

vola-ACC.PL

mōrī

three-C.ACC.PL

'I spent three volar reading'

To denote the amount of time spent on an action, without regard for whether or not the activity was completed or reached its end goal (i.e. atelic action) the essive case is used. To signify the amount of time spent or necessary to spend to complete an activity (i.e. telic action) the instrumental case is used.

iūvint

write.PFV-3PL

te

=1SG

harēnae

letter-ACC.SG

īmau

one-C.ESS.SG

lȳrau

lyra-ESS.SG

'I wrote letters for an hour'

iūva

write.PFV-C.3SG

te

=1SG

harēna

letter-ACC.SG

īmārun

one-C.INSTR.SG

lȳrārun

lyra-INSTR.SG

'I wrote the letter in an hour'

Possession

There are a number of different strategies in Aeranir to signify possession. Aeranir lacks a possession verb analogous to English 'to have,' and instead usually signifies possession through different types of existential clauses. For example, the sentence 'I have a friend' can be expressed by the sentence ēs carīnus tihī, which literally means 'there is a friend to me.'

The case of the possessor changes depending its relationship with the possessed:

- Locative case: used for personal possessions that are currently on the person;

ēs

COP-T.3SG

iarius

spear-NOM.SG

taurātīs

soldier-LOC.SG

lit. 'at the soldier is a spear'

'The soldier has a spear (on them)'

- Dative case: used for personal possessions that are not currently on the person, or for affiliation with persons or people;

sintz

COP-T.3PL

iariur

spear-NOM.PL

vulhur

many-T.NOM.PL

taurātiō

soldier-DAT.SG

lit. 'to the soldier are many spears'

'The soldier has many spears (at home)'

sintz

COP-T.3PL

menterur

sibling-NOM.PL

tihī

1SG-DAT

octzuin

six

lit. 'to me are six siblings'

'I have six siblings'

- Ablative case: used for parts of a whole, or body parts;

sī

COP-E.3SG

incus

head-NOM.SG

iūrun

good-E.NOM.SG

nēnē

1SG-ABL

lit. 'from you is a good head'

'You have a good head (i.e. are smart)'

For metaphorical possession or possession of abstract concepts, such as leadership, power, knowledge, etc., any of these three may be used, for different rhetorical purposes. For example, using the locative implies an immediacy to the possession; that it is in hand, ready to be used. Using the dative implies that the possession is not immediate, but rather something that can be drawn upon, perhaps too vast to 'carry' on one person. This can be more humble or polite than the locative. Using the locative implies that the trait is a fundamental, inalienable, and inherent part of the possessor, rather than something gained or worked for.

Conditionals

Aeranir has a number of ways of expressing conditional sentences, depending on the type of condition, as well as the register of speech. Colloquial or spontaneous speech tends to favour the use of finite dependant clauses for the protasis (conditional clause, as opposed to the apodosis, or consequence), where as practiced or refined speech, or writing, tend to favour non-finite dependant clauses (this represents a general trend in writing to 'nominalise' all but the most central verb in a sentence, and sometimes the central verb too is made non-finite).

sopis

snow-NOM.SG

furea

fall-SUBJ.C.3SG

requeō

return-MID.SUBJ.1SG

cōmerī

home-DAT.SG

(more informal)

'If it snows I'm going home'

soperis

snow-GEN.SG

furentīs

fall-SUBJ.PTCP-T.LOC.SG

requeō

return-MID.SUBJ.1SG

cōmerī

home-DAT.SG

(more formal)

'If it snows I'm going home'

When a non-finite clause is used for a conditional, the verb of the protasis usually appears in the locative case (an expression of time-is-space metaphor), unless the two clauses share an argument (e.g. subject, object, etc.) in which case the protasis takes the same case marking as the shared argument.

Conditional sentences in Aeranir are formed purely through juxtaposition—that is, the placing of two clauses side by side, the verb of the protasis moved to clause-final position or put into a non-finite form to mark it as dependant. No conjunctive particles like 'if' or 'when' are required. The protasis takes the subjunctive mood, whilst the mood of the apodosis indicates the certainty of the conclusion. Aspect, meanwhile, can be used to indicate the certainty of the condition. This distinction may be approximated in English by 'if' versus 'when'

| Protasis certain | Protasis uncertain | |

|---|---|---|

| Apodosis certain | if [perfective aspect] then [indicative mood] e.g. intlae furītīs mollintz tahrer—'when it rains, the shingles will leak' |

if [imperfective aspect] then [indicative mood] e.g. intlae furentīs mollintz tahrer—'if it rains, the shingles will leak' |

| Apodosis uncertain | if [perfective aspect] then [subjunctive mood] e.g. intlae furītīs mollent tahrer—'when it rains, the shingles might leak' |

if [imperfective aspect] then [subjunctive mood] e.g. intlae furentīs mollent tahrer—'if it rains, the shingles might leak' |

Numbers

| # | Cardinal | Ordinal | Adverbial | # | Cardinal | Ordinal | Adverbial | # | Cardinal | Ordinal | Adverbial | # | Cardinal | Ordinal | Adverbial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | īmus | prīstus | temper | 11 | īnhīntur | īnhīnsus | īnhīntin | 21 | calhier īmus | calhitus prīstus | calhin temper | 120 | octzāculhier | octzāculhitus | octzāculhin |

| 2 | sēr | metzumnus | vēriēs | 12 | verhīntur | verhīnsus | verhīntin | 22 | calhier sēr | calhitus metzumnus | calhin vēriēs | 140 | nāculhier | nāculhitus | nāculhin |

| 3 | morier | moritus | moriēs | 13 | prōhīntur | prōhīnsus | prōhīntin | 30 | calhier qehentzier | calhitus qehēnsus | calhin qehen | 160 | nāquenculhier | nāquenculhitus | nāquenculhin |

| 4 | quatlur | quallus | quatziēs | 14 | quatlāhīntur | quatlāhīnsus | quatlāhīntin | 40 | verculhier | verculhitus | verculhin | 180 | nātlicculhier | nātlicculhitus | nātlicculhin |

| 5 | quiquier | quiqtus | quiquin | 15 | quihīntur | quihīnsus | quihīntin | 50 | verculhier qehentzier | verculhitus qehēnsus | verculhin qehen | 200 | tammīttler | tammīttus | tammīttziēs |

| 6 | octzuer | octzūmus | octzuin | 16 | octzāhīntur | octzāhīnsus | octzāhīntin | 60 | prōculhier | prōculhitus | prōculhin | 220 | tammīttler calhier | tammīttus calhitus | tammīttziēs calhin |

| 7 | nāier | nāntus | nāhin | 17 | nāhīntur | nāhīnsus | nāhīntin | 70 | prōculhier qehentzier | prōculhitus qehēnsus | prōculhin qehen | 240 | tammīttler verculhier | tammīttus verculhitus | tammīttziēs verculhin |

| 8 | nāquemur | nāquemmus | nāquemin | 18 | sērēsculhier | sērēsculhitus | sērēsculhin | 80 | quatlāculhier | quatlāculhitus | quatlāculhin | 260 | tammīttler prōculhier | tammīttus prōculhitus | tammīttziēs prōculhin |

| 9 | nātlittzier | nātlittzitus | nātlittzin | 19 | īmāculhier | īmāculhitus | īmāculhin | 90 | quatlāculhier qehentzier | quatlāculhitus qehēnsus | quatlāculhin qehen | 280 | tammīttler quatlāculhier | tammīttus quatlāculhitus | tammīttziēs quatlāculhin |

| 10 | qehentzier | qehēnsus | qehen | 20 | calhier | calhitus | calhin | 100 | quicculhier | quicculhitus | quicculhin | 400 | mīttler | mīttus | mīttziēs |

| # | Cardinal | Ordinal | Adverbial | # | Cardinal | Ordinal | Adverbial | # | Cardinal | Ordinal | Adverbial | # | Cardinal | Ordinal | Adverbial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 800 | vermīttler | vermīttus | vermīttziēs | 16,000 | verittuer | verittūtus | verittuin | 320,000 | verōtluar attuer | verōtluus attūtus | verōtlua attuin | 6,400,000 | verictzuōner | verictzuōnitus | verictzuō |

| 1,200 | prōmīttler | prōmīttus | prōmīttziēs | 24,000 | prōttuer | prōttūtus | prōttuin | 480,000 | prōtluar attuer | prōtluus attūtus | prōtlua attuin | 9,600,000 | prōctzuōner | prōctzuōnitus | prōctzuō |

| 1,600 | quatlāmīttler | quatlāmīttus | quatlāmīttziēs | 32,000 | quatlāttuer | quatlāttūtus | quatlāttuin | 640,000 | quatlōtluar attuer | quatlōtluus attūtus | quatlōtlua attuin | 12,800,000 | quatlictzuōner | quatlictzuōnitus | quatlictzuō |

| 2,000 | quimīttler | quimīttus | quimīttziēs | 40,000 | quiquittuer | quiquittūtus | quiquittuin | 800,000 | quiqōtluar attuer | quiqōtluus attūtus | quiqōtlua attuin | 16,000,000 | quictzuōner | quictzuōnitus | quictzuō |

| 2,400 | octzāmīttler | octzāmīttus | octzāmīttziēs | 48,000 | octzāttuer | octzāttūtus | octzāttuin | 960,000 | octzōtluar attuer | octzōtluus attūtus | octzōtlua attuin | 19,200,000 | vulhiāhur | vulhiātus | vulhiāhin |

| 2,800 | nāmīttler | nāmīttus | nāmīttziēs | 56,000 | nāttuer | nāttūtus | nāttuin | 1,120,000 | nōtluar attuer | nōtluus attūtus | nōtlua attuin | 22,400,000 | nōctzuōner | nōctzuōnitus | nōctzuō |

| 3,200 | nāquemīttler | nāquemīttus | nāquemīttziēs | 64,000 | nāquemittuer | nāquemittūtus | nāquemittuin | 1,280,000 | nāquemōtluar attuer | nāquemōtluus attūtus | nāquemōtlua attuin | 25,600,000 | nāquemictzuōner | nāquemictzuōnitus | nāquemictzuō |

| 3,600 | nātlimīttler | nātlimīttus | nātlimīttziēs | 72,000 | nātlittzittuer | nātlittzittūtus | nātlittzittuin | 1,440,000 | nātlittzōtluar attuer | nātlittzōtluus attūtus | nātlittzōtlua attuin | 28,800,000 | nātlictzuōner | nātlictzuōnitus | nātlictzuō |

| 4,000 | tamittuer | tamittūtus | tamittuin | 80,000 | tamōtluar attuer | tamōtluus attūtus | tamōtlua attuin | 1,600,000 | tamictzuōner | tamictzuōnitus | tamictzuō | 32,000,000 | tamōtluar octzuōner | tamōtluus octzuōnitus | tamōtlua octzuō |

| 8,000 | attuer | attūtus | attuin | 160,000 | ōtlua attuer | ōtlua attūtus | ōtlua attuin | 3,200,000 | octzuōner | octzuōnitus | octzuō | 64,000,000 | ōtlua octzuōner | ōtlua octzuōnitus | ōtlua octzuō |

Late Aeranir inovations

Applicative voices

Whilst Classical Aeranir was more permissive of adding additional arguments to a clause, so long as the verb's core transitivity were met. Late Aeranir, however, tended to be more restrictive, and required valency increasing operations to express benefactive, comitative, and locative meanings. These applicative morphemes take the form of verbal prefixes.