Aeranir: Difference between revisions

(→Vowels) |

|||

| Line 312: | Line 312: | ||

|- style="text-align:center;" | |- style="text-align:center;" | ||

! Mid-open | ! Mid-open | ||

| | | æ<br>/ɛ/ | ||

! rowspan="2" | | ! rowspan="2" | | ||

| | | ꜵ<br>/ɔ/ | ||

|- style="text-align:center;" | |- style="text-align:center;" | ||

! Open | ! Open | ||

Revision as of 13:22, 12 October 2019

| Aeranir | |

|---|---|

| coeñar inderis | |

| coeñar aerānir | |

| Pronunciation | [[Help:IPA|[[ˈcʰøː.ɲar ˈɪ̃n.t̪ɛ.rɪs̠], [ˈcʰøː.ɲar ɛːˈraː.nɪr]]]] |

| Created by | Limius |

| Setting | Avrid |

| Native to | Telrhamir, Iscaria, Aeranid Empire |

| Ethnicity | Aeran |

Maro-Ephenian

| |

Early forms | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Aeranid Empire |

Recognised minority language in | |

Aeranir, also known as coeñar aerānir (language of the Aerans), or coeñar inderis (language of the capital), is an Iscaric language in the Maro-Ephenian language group. It was originally spoken by the Aerans, developed in the deserts of Northern Iscaria in the city of Telrhamir, and spread with the expanse of the Aeranid Empire throughout Ephenia, as well as parts of Eubora and Syra. It later developed into the Aeranid languages, such as Dalot, Ilesse, Iscariano, Îredese, S'entigneis, and Tevrés. It is still used throughout Ephenia as a language of theology, science, medicine, literature, and law.

Aeranir had been standardised into Classical Aeranir by the time of the Early Empire, around the second millennia BNIA by the writer and educator Limius. The period before that is generally referred to as Old Aeranir. The language spoken between the 15th and 12th centuries BNIA is generally referred to Late Aeranir. This shift is marked by several grammatical and phonetic shifts. After that period, Aeranir began to splinter off into the various Aeranid languages. A form of Classical Aeranir called New Aeranir or Medieval Aeranir remained in use in official writings even after this period.

Aeranir is a highly infective and fusional language, with three distinct genders, nine cases, two aspects, four moods, three persons, two or three voices, and two numbers.

History

Old Aeranir

The oldest attested form of Aeranir is Old Aeranir, which was spoken in the kingdom of Telrhamir circa 2300 BNIA. It is attested mostly in inscriptions found in and around the Great Desert, and in some early remaining Aeranid literary works. Old Aeranir lacked many of the verb-forms found in Classical Aeranir, such as the potential and causative moods, and the passive voice (which was marginal even in Classical Aeranir). Old Aeranir had an additional declension class, the i-stem declension, which merged with the consonant-stems in Classical Aeranir. Proto-Iscaric diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/, as well as initial /gn/ and non-affricate /ts/ were retained in Old Aeranir, and it is believed that Classical /ɛː ɔː øː yː/ remained diphthongs /ai au oi ui/ (and were thus written ai au oi ui, as opposed to Classical ae au oe ȳ). In general, Old Aeranir lacked much of the vowel diminishing that characterised Classical Aeranir.

Classical Aeranir

A standardised form of the language arouse in the time of the Early Empire, created conciously by the prominent grammarians, writers, and orators of the time. This formed the basis of what was taught in the Telrhamiran axēs system. One of the most prominent of these figures was Limius (who was known in their day as Lēctica Prīstus Limius Vestil Oscānus Fellentīmā Motā Soniae) who is credited with first marking diminished vowels in writing.

Phonology

Consonants

The following is a table of phonemes in Aeranir. This analysis is based on Classical Aeranir, as it was used during the hight of the Aeranid Empire. The phonology, especially the number of vowel phonemes, varied greatly time, but this is seen as the standard version of the language.

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dental | lateral | post- alveolar |

plain | labial | plain | labial | |||||

| Nasal | m /m/ |

n /n/ |

ñ /ɲ/ |

||||||||

| Stop | aspirated | p /pʰ/ |

t /t̪ʰ/ |

tl /tɬʰ/ |

ȥ /ts̠ʰ/ |

c /kʰ/ |

cu /kʷʰ/ |

q /qʰ/ |

qu /qʷʰ/ |

||

| plain | b /p/ |

d /t̪/ |

g /k/ |

gu /kʷ/ |

|||||||

| Fricative | f /f/ |

δ /ð/ |

s /s̠/ |

γ /ɣ/ |

h /h/ | ||||||

| Trill | voiceless | rh /r̥/ |

|||||||||

| voiced | r /r/ |

||||||||||

| Approximate | v /ʋ/ |

l /l/ |

i /j/ |

||||||||

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dental | lateral | post- alveolar |

plain | labial | ||||

| Nasal | m /m/ |

n /n/ |

ñ /ɲ~j̃/ |

|||||

| Stop | voiceless | p /p/ |

t /t̪/ |

tl /tɬ/ |

ȥ /ts̠/ |

tz /c/ |

c, q /k/ |

cu, qu /kʷ/ |

| voiced | b /b/ |

d /d̪/ |

z /ɟ/ |

g /g/ |

gu /gʷ/ | |||

| Fricative | f /f/ |

s /s̠/ |

||||||

| Trill | r /r/ |

|||||||

| Approximate | l /l/ |

|||||||

Notes on consonants

- The sequences /ps/, /ks/, and /qs/ are written in the romanisation as ψ, x, and ξ respectively, to reflect native orthography.

- The voiceless stops are aspirated alophonically in the onset of stressed syllables.

- The nasal consonant /n/ assimilates to the place of articulation of the following stop, so that /nkʰ/ or /nqʷʰ/ for example become /ŋkʰ/ and /ɴʷqʷʰ/. Before fricatives, /n/ is deleted, and the proceeding vowel is lengthened and nasalised. These processes apply between word boundries as well. Word final /n/ as part of case and personal markers is elided before a word starting with a vowel, fricative, approximate, or before a pausa.

- The phoneme /ɣ/ has the greatest variance of all Aeranid phonemes, varying between dialects and even between individual speakers from [ɰ~ɣ~ʁ~ʀ~ɢ~ʕ~ɦ~Ø]. It often served as a shibboleth for discerning one's origins or social circles.

- The velar, labio-velar, and labio-uvular consonants /kʰ/, /k/, /kʷʰ/, /kʷ/, and /qʷʰ/ are palatalised before front vowels and /j/ to [cʰ], [c], [kᶣʰ], [kᶣ], and [qᶣʰ] respectively. Futhermore, dental consonants /n/, /tʰ/, and /t/ are palatalised before /j/ to [ɲ], [cʰ], and [c]. The glottal fricative /h/ is also palatalised to [ç] before high front vowels and /j/. Some dialects also palatalise the postalveolar consonants /s̠/ and /ts̠ʰ/ to [ɕ] and [tɕʰ] before front vowels and /j/. In dialects were /ɣ/ is velar, it is often palatalised to [ʝ] in the same enviorments as the other velar consonants.

- The labialised consonants /kʷʰ/, /kʷ/, and /qʷʰ/ are pronounced as truly labialised, rather than a sequence of two consonants, i.e. /kʰw/, /kw/, /qʰw/. The voiced labiovelar stop only occurs after a nasal consonant.

- All consonants, with the exception of /ʋ/, can be geminated between vowels. This is denoted orthographically by doubling of the first letter of the phoneme, i.e. ⟨cc⟩, ⟨ff⟩, ⟨rrh⟩, etc. The palatal approximate /j/ is always geminated to [jː] between vowels, but is written with a simple ⟨i⟩. Fricative /hː/ is usually realised as [çː], however in dialects with uvular or pharyngeal articulation of /ɣ/, it is usually backed to match that articulation. In dialects that palatalise /s̠/ and /ts̠ʰ/, [çː] often becomes [ɕː], merging in some environments with /s̠ː/.

- The lateral approximate /l/ has two allophones in Classical Aeranir; [l] before close front vowels, /j/, and when geminated, and [ɫ] elsewhere.

- The affricate /ts̠ʰ/ is in most cases pronounced less retracted than fricative /s̠/, and may be closer to a purely alveolar [tsʰ].

Vowels

Vowels in Aeranir underwent the greatest amount of change throughout time. Although the standard is considered to me Classical Aeranir as it was spoken in the 17th and 16th centuries bnia, this should not be seen in the context of a sliding historical spectrum. Below are listed three somewhat representative samples that provide a broad overview of general changes.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i • ī /i/ • /iː/ |

u • ū /u/ • /uː/ | |

| Mid | e • ē /e̞/ • /e̞ː/ |

o • ō /o̞/ • /o̞ː/ | |

| Open | a • ā /a/ • /aː/ |

||

| Diphthongs | iu /iu̯/ ei /ei̯/ |

ai • au /ai̯/ • /au̯/ |

ui /ui̯/ oi • ou /oi̯/ • /ou̯/ |

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | rounded | |||

| Close | i • ī /ɪ/ • /iː/ |

y • ȳ /ʏ/ • /yː/ |

u • ū /ʊ/ • /uː/ | |

| Mid-close | ē /eː/ |

oe /øː/ |

ō /oː/ | |

| Mid-open | e • ae /ɛ/ • /ɛː/ |

o • au /ɔ/ • /ɔː/ | ||

| Open | a • ā /a/ • /aː/ | |||

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | round | |||

| Close | i /i/ |

(y) (/y/) |

ë /ɨ/ |

u /u/ |

| Mid-close | e /e/ |

(œ) (/ø/) |

o /o/ | |

| Mid-open | æ /ɛ/ |

ꜵ /ɔ/ | ||

| Open | a /a/ |

|||

Notes on vowels

- Orthographic a and e represent the same sound, the ultra short front open vowel [æ]. The difference is that velar consonants before e are palatalised, whilst they are maintained before a.

- The short high rounded vowel /ʏ/ is a loan from Dalitian, and is not found in any native words, or words dating back to Old Aeranir. It is usually realised as [ɪ], and is only rounded in educated speech.

| PME | Old | Classical | Late |

|---|---|---|---|

| *uHi | → ui /ui̯/ | → y /yː/ | → i /i/ |

| *iHu | → iu /iu̯̯/ | ||

| *ey, *ehi, *ēy, *hey | → ei /ei̯/ | → ī /iː/ | |

| *iH | → ī /iː/ | ||

| *i | → i /i/ | → i /ɪ/ | → e /e/ |

| *oy, *oHi, *eħʷi, *ōy, *Hoy, *ħʷey |

→ oi /oi̯/ | → oe /øː/ | |

| *eh, *ē | → e /eː/ | → e /eː/ | |

| *e | → e /e/ | → e /ɛ/ | → ĕ /ɛ/ |

| *eħi, *ħey | → ai /ai̯/ | → ae /ɛː/ | |

| *ow, *oHu, *ōw, *How, *ħʷew, *ew, *ehu, *ēw, *hew |

→ ou /ou̯̯/ | → ū /uː/ | → u /u/ |

| *uH | → ū /uː/ | ||

| *u | → u /u/ | → u /ʊ/ | → o /o/ |

| *oH, *ō, *ħʷeH, *ħʷē, *eħʷ |

→ o /oː/ | → o /oː/ | |

| *o, *ħʷe | → o /o/ | → o /ɔ/ | → ŏ /ɔ/ |

| *eħu, *ħew | → au /au̯̯/ | → au /ɔː/ | |

| *eħ, *ħē | → ā /aː/ | → ā /aː/ | → a /a/ |

| *H̩ | → a /a/ | → a /a/ |

- Most non-intial short vowels in Proto-Iscairc were reduced to /i/ by the time of Old Aeranir. Many of these were then further reduced in Classical Aeranir (as discussed above), to the vowels represented by diaeresis. These merged in Late Aeranir to a schwa, but this schwa was deleted in many environments.

- Old Aeranir diphthongs /ei̯/ and /ou̯̯/ may have been realised as hightened pure vowels [eː~e̝ː] and [oː~o̝ː]. Before other vowels, /ei̯/ becomes simple [e] in Classical Aeranir. Likewise, Classical /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ rise to [e] and [o] before another vowel. These were then simplified into glides [j] and [w] in Late Aeranir.

- There are two realisations of high short vowels /ɪ/ and /ʊ/ before another vowel, depending on whether the proceeding syllable it light or heavy. Following a light syllable, the become glides [j] and [w]. Follwing a heavy syllable, an anaptyctic vowel is inserted, becoming [ɪj] and [ʊw]. These vowels are not represented in the orthography.

- Some peripheral dialects of Late Aeranir retained rounded front vowels /y/ and /ø/, while in most, including the speech of Telrhamir, they merged with their plain counterparts /i/ and /e/ respectively.

Stress

Syllable stress in Old Aeranir fell uniformly on the first syllable of a word. However, by the time of Classical Aeranir, stress had shifted to a more complex paradigm, generally falling on the penult (the second to last syllable) or the antipenult (the third to last syllable). Which one was determined by the weight of the penult.

Syllables are divided into one of two categories, or weights. These are light syllables and heavy syllables. A light syllable contains a maximum of one short vowel, alone or proceeded by a consonant or consonant cluster, while a heavy syllable may contain a long vowel, a coda consonant, or both. If the penult of a word is heavy, it is stressed. If not, the antipenult is stressed.

Nouns

Gender

Aeranir nouns are divided into three genders, all of which are directly inherited from late Proto-Maro-Ephenian. These known as the temporary (t), cyclical (c), and eternal (e) genders. The gender of a noun effects the adjectives and verbs that refer to it.

ēs

COP.3SG.T

ar[d]

wumbo(T)

-s

-NOM.SG

rhai

small

-us

-T.NOM.SG

'It's a small wumbo.'

sa

COP.3SG.C

tlān

flower(C)

-a

-NOM.SG

rhai

small

-a

-C.NOM.SG

'It's a small flower.'

se

COP.3SG.E

nātl

shell(E)

-un

-NOM.SG

rhai

small

-un

-E.NOM.SG

'It's a small shell.'

The gender of most nouns can be easily inferred from its ending. Furthermore, there is often overlap between meaning and gender. Animate living beings and small, breakable objects are often temporary, while abstract concepts, natural processes, or seasonal plants are usually cyclical, and large, durable, inanimate objects are most likely eternal. However, some nouns have no relation to their gender. Personal names are either temporary or cyclical; eternal names are reserved for gods.

Case

Nouns in Aeranir have a series of different forms, called cases of the noun, which have different functions or meanings. For example, the word for 'king' is rēs when subject of a verb, but rēnin when it is the object:

- augēs rēs 'the king sees (someone)' (nominative case)

- augēs rēnin '(someone) sees the king' (accusative case)

There are a total of nine cases for most nouns in Aeranir. Outside of the nominative and accusative, they are as the following:

- Vocative: rēne iō!: 'o king!'

- Essive: seū rēnū: 'as this king'

- Instrumental: seōrun rēnerun: 'using this king'

- Genitive: sī rēnis: 'of this king'

- Dative: seō rēnī: 'to/for this king'

- Ablative: seā rēnī: 'from/by this king'

- Locative: sīs rēnīs: 'at/with the king'

Sometimes the same endings, e.g. -ī and -ēs, are used for more than one case. Since the function of a word in Aeranir is shown by ending rather than word order, in theory requor rēnī could mean either 'I return to the king' or 'I return from the king.' In practice, however, such ambiguities are rare.

Declensions

Class I

| salva c. book, tome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||||

| word | ending | word | ending | ||

| Primary prīstūmus |

Nominative | salva | -a | salvar | -ar |

| Accusative | salvan | -an | salvae | -ae | |

| Vocative | salva | -a | salvar | -ar | |

| Existential soniāmus |

Essive | salvau | -au | salvur | -ur |

| Instrumental | salvārun | -ārun | salvōs | -ōs | |

| Genitive | salvae | -ae | salvābus | -ābus | |

| Directive satūmus |

Dative | salvō | -ō | salvāna | -āna |

| Ablative | salvā | -ā | salvās | -ās | |

| Locative | salvīs | -īs | salvā | -ā | |

Class II

| bernus t. storm, chaos |

nātlun e. shell, carapace | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | ||||||

| word | ending | word | ending | word | ending | word | ending | ||

| Primary prīstūmus |

Nominative | bernus | -us | bernur | -ur | nātlun | -un | nātlunt | -unt |

| Accusative | bernun | -un | bernī | -ī | |||||

| Vocative | berne | -e | bernur | -ur | |||||

| Existential soniāmus |

Essive | bernū | -ū | bernur | -ur | nātlū | -ū | nātlur | -ur |

| Instrumental | bernōrun | -ōrun | bernōs | -ōs | nātlōrun | -ōrun | nātlōs | -ōs | |

| Genitive | bernī | -ī | bernōbus | -ōbus | nātlī | -ī | nātlōbus | -ōbus | |

| Directive satūmus |

Dative | bernō | -ō | bernōna | -ōna | nātlō | -ō | nātlōna | -ōna |

| Ablative | bernā | -ā | bernōs | -ōs | nātlā | -ā | nātlōs | -ōs | |

| Locative | bernīs | -īs | bernā | -ā | nātlīs | -īs | nātlā | -ā | |

Pronouns

Personal Pronouns

| First person | Second person | Reflexive | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular I |

plural we |

singular you |

plural y'all |

singular/plural himself/herself/ itself/themselves | |||||||||

| full | clitic | full | clitic | full | clitic | full | clitic | full | clitic | ||||

| Primary prīstūmus |

Nominative | aecū | te | eōs | ī | hanae | ne | rōs | er | cē | ce | ||

| Vocative | |||||||||||||

| Accusative | tē | eon | nē | ron | |||||||||

| Existential soniāmus |

Essive | tōs | eor | nōs | rō | cū | |||||||

| Genitive | tī | īster | nī | rester | cī | ||||||||

| Directive satūmus |

Dative | tivī | īvīs | nivī | urvīs | civī | |||||||

| Ablative | tētē | eōvōs | nēnē | rōvōs | cēcē | ||||||||

Possessive pronouns

Possessive pronouns in Aeranir distinguish between many more different types of possession than ordinary nouns, which use only the genitive to mark possession, ownership, association, etc. Pronouns distinguish both alienable and inalienable possession, and may also mark the degree of control the possessor has over the possessee.

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | reflexive | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proximal | distal | medial | |||||||||

| singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | ||

| inalienable | tī teī |

īster | nī neī |

rester | sī seī |

seōδus | ūlī | ūlōδus | ustī | ustōδus | cī ceī |

| alienable | tuius | eius | nuius | ruius | sīrius | sūrius | ūluius | ūlurius | ustuius | usturius | cuius |

| subjective | tēteius | īvīsius | nēneius | urvīsius | seārius | seōsius | ūlārius | ūlōsius | ustārius | ustōsius | cēceius |

| objective | tivius | eōvōsius | nivius | rōvōsius | seōrius | seōnārius | ūlōrius | ūlōnārius | ustōrius | ustōnārius | civius |

Objects of inalienable possession are marked with the genitive of a personal or demonstrative pronoun. These include body parts, kinship and familiarity terms, personal attributes, emotions, or thoughts. These pronouns generally proceed the possessee, although that is not always the case, especially in poety. Singular pronouns tī, nī, cī, sī, ustī, and ūlī may be appear as tei, nei, cei, sei, usti, ūli before words starting with a vowel, and te, ne, ce, se, ust, ūl before words starting with i.

se

this

-[ī]

-T.GEN.SG

indus

head

-Ø

-NOM.SG

'this one's head'

Alienable possession, including essentially all other categories, is marked via possessive adjectives. These adjective may appear either before or after the possessee, but usually come afterwards. Oftentimes, the different use of alienable/inalienable pronouns may hint at a difference in meaning. The word indus, for example, may mean 'head,' but also 'capital' or 'leader.' With inalienable pronouns, however, it always means 'head,' versus with alienable pronouns, it means 'capital,' or 'leader' because while a head is inalienable, a capital or leader is not. However, this might not always be the case, depending on the possessor and context.

'My capital is telrhamir'

'It's (the Aeranid Empire's) capital is telrhamir'

Verbs

Conjugation

Agreement

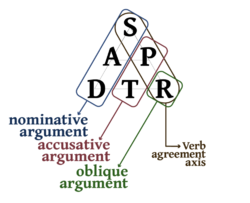

Verbs in Aeranir are conjugated to agree with the number, the person, and in the third person singular, the gender of the most oblique argument given a word's valency, as defined by the DGA pyramid[1]. Here, S represents the subject of an intransitive verb, such as 'the person' in 'the person laughed.' A represents the agent of a transitive verb (also occasually called the subject), or the person or thing that does the action of the verb, such as 'the child' in 'the child reads the book.' D marks the donor, a special type of agent, who gives something or does a the action of a verb for the benefit of another, such as ‘the senator’ in ‘the senator gave the cat some milk.’ These are collectively called the nominative argument, and are expressed usually with the nominative case, but also occasionally with the genitive case in dependant clauses.

P represents the patient of a transitive verb, or the person or thing towhich the verb is done, also called the direct object, such as ‘the book’ in ‘the child reads the book.’ T represents the theme, or the object that is given to someone or something, such as ‘the milk’ in ‘the senator gave the cat some milk.’ These two roles make up the accusative argument, which is marked with the accusative case. Finally, R represents the recipient, or the person who recieves the theme from the donor, or benefits from the donor's action, with a ditransitive verb, also commonly called the indirect object, such as 'the cat' in 'the senator gave the cate some milk.'

Aeranir verbs conjugate their endings to agree with the most oblique argument in a clause. That means the subject of an intransitive verb (e.g. claudiȥ; 'I laugh'), the patient of a transitive verb (e.g. augente; 'I look at you'), or the recipient of a ditransitive verb (e.g. ȥavīȥe salvae; 'you all gave me the books'). It should be noted that a verb in the active voice must always have the maximum number of arguments according to its inherent transitivity. This means, for example, that one can never say 'John eats.' Because 'to eat' is transitive, there must be a patient, or direct object, e.g. 'John eats food.' However, there are a number of valancy dropping operations available in Aeranir to allow various arguments to be dropped, which are discussed in the section on voice.

Additional arguments can be expressed with pronominal clitics attached to the end of a verb in independant clauses and to the beginning in dependant ones (e.g.augente; 'I look at you,' ȥāvīȥe salvae; 'you all gave me the books'), however these are not considered part of a verbs conjugation, and are optional, especially if the information can be assumed or is known between speakers.

Number of Conjugations

| Aspect → | Imperfective | Perfective | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood → Voice ↓ |

Indicative | Subjunctive | Desiderative | Potential | Indicative | Subjunctive | Desiderative | Potential |

| Active | aedaȥ They love me |

aedet They should love me |

aedārit They want to love me |

aedātaȥ They can love me |

aedāvī They loved me |

aedēvī They should have loved me |

aedāruī They wanted to love me |

aedātāvī They could have loved me |

| Middle | aedor I love |

aedeō I should love |

aedārō I want to love |

aedātor I can love |

aedāvō I loved |

aedēvō I should have loved |

aedāruō I wanted to love |

aedātāvō I could have loved |

| Passive | aedālō I am loved |

aedēlō I should be loved |

aedārēlō I want to be loved |

aedātālō I can be loved |

aedāvēlō I was loved |

aedēvēlō I should have been loved |

aedāruēlō I wanted to be loved |

aedātāvēlō I could have been loved |

| Causative | aedātiȥ They let me love them |

aedātiat They should let me love them |

aedātīrit They want to let me love them |

aedāssītaȥ They can let me love them |

aedātīvī They have let me love them |

aedātiāvī They should have let me love them |

aedātīruī They wanted to let me love them |

aedāssītāvī They could have let me love them |

Principle Parts

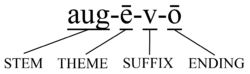

The verb in Aeranir is primarily made of three parts: stem, theme, and ending, with an optional forth category, the suffix, for forming the perfective. The stem carries the semantic content of the word, and can also be conjugated to carry modal imformation. The theme describes how the stem interacts with the ending, and can also be changed, along with the stem and endings, to express a variety of different grammatical meanings. Endings indicate the voice, aspect, person, number, and gender of the most oblique argument in the DGA scheme.

| Active | Middle | Passive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperfective | Perfective | Imperfective | Perfective | Imperfective | Perfective | |||

| Singular | 1st Person | -iȥ/-it | -ī | -or/-ō | -ō | -ēlō | -ēlō | |

| 2nd Person | -in | -in | -istī | -iste | -ēlāstī | -ēlāste | ||

| 3rd Person | temporary | -is | -is | -erur | -ere | -ēlārur | -ēlāre | |

| cyclical | -a | -a | -erra | -ēlārra | ||||

| eternal | -ī | -e | -erur | -ēlārur | ||||

| Plural | 1st Person | -imus | -ime | -imur | -imur | -ēlāmur | -ēlāme | |

| 2nd Person | -itis | -ite | -itur | -itur | -ēlātur | -ēlāte | ||

| 3rd Person | -enȥ/-end | -end | ||||||

The way in which a verb will conjugate can be determined from how it forms the following five constructions:

- the active idicative imperfective first person singular

- the active imperfective accusative infinitive

- the active perfective participle

- the active desiderative imperfective first person singular

- the active indicative perfective first person singular

These five forms are refered to as a verb's reference forms. They are often shortend to first person singular (1p.sg), accusative infinitive (acc.inf), perfective participle (pfv.ptcp), desiderative first person singular (des.1p.sg), and perfective first person singular (pfv.1p.sg) respectively.

The first two of these reference forms determines a verb's base theme vowel, or what vowel is used in its indicative imperfective forms. There are four main thematic classes; one weak or null class, wherein the ending is applied directly to the stem, and three strong classes, wherein a thematic vowel is inserted between the stem and the ending.

| t-stem | s-stem | |

|---|---|---|

| -m- | → -mbt- | → -s-* |

| -n- | → -nt- | |

| -ñ- | → -ñgt- | |

| -p- | → -bt- | → -ψ- |

| -t- | → -ss- → -s-** |

→ -ss- → -s-** |

| -tl- | ||

| -ȥ- | ||

| -c- | → -gt- | → -x- |

| -cu- | ||

| -q- | → -qt- | → -ξ- |

| -qu- | ||

| -b- | → -bt-* | → -ψ-* |

| -d- | → -s-* | → -s-* |

| -g- | → -gt-* | → -x-* → -s-† |

| -s- | → -st- | → -ss- → -s-** |

| -r- | → -st- → -s-** → -rt-†† |

→ -ss- → -s-** → -rr-†† |

| -l- | → -s-** → -lt-†† |

→ -s-** → -ll-†† |

| -v- | → -ut-‡ → -ct-*†† → -qt-*†† |

→ -ur-‡ → -x-*†† → -ξ-*†† |

| -i- | → -ct-* → -qt-*†† |

→ -x-* → -ξ-*†† |

| -gh- | ||

| -V- | → -Vt- | → -Vr- |

| Ending | Theme | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| -ā- | -ē- | -ī- | |

| -iȥ | → -aȥ | → -eȥ | → -iȥ |

| -is | → -ās | → -ēs | → -īs |

| -a | → -a | → -ea | → -ia |

| -ī | → -ae | → -ī | → -ī |

| -imus | → -āmus | → -ēmus | → -īmus |

| -or | → -or | → -eor | → -ior |

| -ēlō | → -ālō | → -ēlō | → -iēlō |

The second two determine a verbs's t-stem and s-stem. These stem alterations are used for further conjugation, the t-stem forming the active and middle perfective participles, the causative voice, and the potential mood, and the s-stem forming the desiderative. The t- and s-forms often are identical, however meaning is useally further differentiated by thematic vowels, so completely identical forms are rare.

The final form determines how a verb with form the perfective aspect. Generally, there are three main strategies for this: the application of suffix -u- directly after the stem (e.g. oeliȥ ("I work") → oeluī ("I worked")), the appication of the suffix -v- after a theme vowel (e.g. aedaȥ ("they love me") → aedāvī ("they loved me")), or no suffix, with lengthening of the root vowel (e.g. legiȥ ("I choose") → lēgī ("I chose")). It should be noted that the perfective is always followed by weak endings.

Occassionally, a thematic vowel, weak or strong, may be inserted before the t- or s-stem. This is most common in verbs with a base thematic -ā-, which often functions as a part of the stem (e.g. aedaȥ → aedātus ("that loved") aedārit ("they want to love me") vs. mavaȥ ("I wander") → mautus ("that wandered") maurit ("I want to wander)). This may occur with other theme classes, although it should be noted that -ē- is never used, and is always replaced with -ī-.

Aspect

Aeranir verbs have two basic aspects, which express how the verb extends over time. Aspect differs from tense in that it deals with the completion or continuity of an action or state, rather than the absolute timeframe inwhich it took place. Each aspect may be in any voice and/or mood. Aspect is expressed primarily through endings, and secondarily through the suffix, as discussed above.

Imperfective

The imperfective aspect describes a situation viewed with interior composition. It describes ongoing, habitual, or repeated situations, rather or not they occured in the past, present, or future. The imperfective aspect is considered the most basic, unmarked aspect of a verb. The stem is uninflected, and endings are attached directly to the verb's basic theme vowel.

Pefective

The perfective aspect in Aeranir describes situations viewed with exterior composition, which is to say actions which are completed and viewed as a unified whole, whether thet take place in the past present, or future, although this construction is very rarely used in for the future.

There are a variety of different strategies to form the perfective. Many of them involve the suffix, which takes the form of -v- between vowels and -u- after consonants. All of them take the perfective endings.

- Attachment of the suffix directly to the stem.

- Attachment of the suffix after base thematic vowel.

- praeffiliaȥ ("they are paying me") → praeffiliāvī ("they payed me")

- augeȥ ("they are looking at me") → augēvī ("they looked at me")

- No suffix; perfective endings attached directly to the stem, with root vowel lengthening.

Mood

Indicative

The indicative mood is the baseline grammatical mood in Aeranir. It is used in declarative statements, to express statements or facts, of what the speaker considers true or known. It is the least marked mood of a verb, taking endings directly to the base theme vowel, stem, or suffix.

Subjunctive

The subjunctive mood (subj) has numerous, but genreally speaking is used to express such nuances as 'would,' 'should,' or 'may.' It can be used to refer to information that the speaker is unsure about, such as hearsay, or for theoretical or hypotherical situations. It is often found in subordinate clauses, annd may be used for conditional statements (e.g. if..., when...).

| Type | Change | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Verbs | -ø- → -ē- | mendiȥ → mendet | |

| -ē- → -ā- | mendēlō → mendālō | ||

| Strong Verbs |

a-stem | -ā- → -ē- | aedaȥ → aedet aedālō → aedēlō |

| i-stem | -ī- → -iā- | saepiȥ → saepiat | |

| -iē- → -iā- | saepiēlō → saepiālō | ||

| e-stem | -ē- → -eā- | cōreȥ → cōreat cōrēlō → cōreālō | |

Forming the subjunctive

The subjunctive is formed by shifting a verb's base theme vowel, as described by the table to the left. This shift happens after the stem, but may be either before or after the suffix, depending on whether or not there is a theme vowel before the suffix in the indicative. So the perfective of aedēs ("they should love it") is aedēvis (from indicative aedāvis) but saepiās ("they should cut it") is saepuēs (from indicative saepuis), not **aedāvēs or **saepēvis. Although these forms are occasionally found in non-standard writing, they are considered incorrect my grammaticians.

The imperfective subjunctive uses the 1st person sungular -it instead of -iȥ, and -ō instead of -or: paciȥ, pacior ("they take me, I take") become paciat, paciō ("they should take me, I should take").

The 1st person subjunctive perfective in verbs that have no theme vowel before the suffix and does not extend the root vowel is identical to the indicative, and the mood must be inferred through conext: saepuī may be either "they cut me" or "They should cut me." The 3rd person active cyclical singulars in verbs with base theme vowels -ī- and -ē- are also identical, e.g. both pacia ("they take it/they should take it"), augea ("they see it/they should see it").

Uses of the subjunctive

The subjunctive has numerous uses, ranging from what potentially might be true to what the speaker wishes or commands should happen. It is often translated with 'should', 'could', 'would', 'may' and so on, but in certain contexts it is translated as if it were an ordinary indicative verb.

One use of the subjunctive is the speculative subjunction, used when the speaker imagines what potentially may, might, would, or could happen in the present or future or might have happened in the past. Negation for this type uses mū.

aug

see

-eārur

-MID.SUBJ.3SG.E

se

this

-un

-E.NOM.SG

oel

job

-iun

-NOM.SG

stēr

hard

-ē

-ADV

'This job seems difficult.'

moei

please

-ea

-SUBJ.3SG.C

oscul

Little.Oscus

-an

-ACC.SG

ȥat

gift

-ū

-ESS.SG

salv

book

-a

-NOM.SG

'Little Oscus may like a book as a gift.'

The subjunctive may also be used as the optative subjunctive, expressing what the speaker wishes may happen, or wishes had happened. These expresses a weaker or more generalised desire, as opposed to the desiderative mood. Negation for this type uses mū.

c

come

-iāvis

-PFV.SUBJ.3SG.T

mū

NEG

se

this

-us

-T.NOM.SG

inder

capital

-ī

-DAT.SG

bern

storm

-us

-NOM.SG

'If only this storm hadn't come to the capital!'

The jussive subjunctive can be used for commands or suggestions for what should happen. It is less direct and far more common than the imperative. Negation for this type uses mīm.

v

go

-en

-SUBJ.2SG

hān

temple

-ō

-DAT.SG

e[x]

against

vec

curse

-ō

-DAT.SG

ven

win

-iend

-GER

-ō

-DAT

'You should go to the temple to prevail against the curse.'

Perhaps the most common use of the subjunctive is the conditional subjunctive. When the subjunctive is used in a subordinate clause (with the verb moving to the final position), it may carry the meaning 'if, when, should, etc..' This can be used both in finite verb forms, and with participles, the former being more popular in Old inscriptions and the later in Classical ones. Negation for this type uses mīm.

Desiderative

The desiderative is used primarily to express wants or desires. While the subjunctive may be used for this as well (see optative subjunctive), the desiderative is considered less abstract or wishful, signalling concrete and actionable wants. It is formed from the s-stem of a verb, with no theme vowel between it and the ending, and using the secondary first person singular and third person plural markers (e.g. -it and -end vs. primary -iȥ and -enȥ). Verbs generally follow three patterns to form the s-stem;

- -s- is appended to the root, causing no other alteration to the root.

- -s- is appended after a theme vowel, causing -s- to become -r-.

- praeffiliaȥ ("they are paying me") → praeffiliārit ("they want to pay me")

- augeȥ ("they are looking at me") → augerit ("they want to look at me")

- -s- is appended to the root, causing some alteration to the root, and perhaps the -s- augment as well.

Potential

The potential mood indicates that, in the opinion of the speaker, one has the ability or capability to do something. It should not be confused with the subjunctive mood, which may be used to express that something is likely or possible to occur. The potential always deals with ability. It may be formed from the t-stem of a verb, plus the thematic vowel -a- (as opposed to the causative voice, which is formed with the t-stem plus the thematic vowel -i-). Like the desiderative, there are three main paradigms by which the t-stem of a verb is formed;

- -t- is appended to the root, causing no other alteration to the root.

- -t- is appended after a theme vowel.

- praeffiliaȥ ("they are paying me") → praeffiliātaȥ ("they can pay me")

- augeȥ ("they are looking at me") → augitaȥ ("they can look at me")

- -t- is appended to the root, causing some alteration to the root, and perhaps the -t- augment as well.

It should be noted that in the causative voice of the potential mood, the first -t- augment often dissimilates to -s/ss-;

- augitiȥ ("they let me look at it") → **augitītaȥ → augissītaȥ ("they can let me look at it")

- reqtiȥ ("they let me return it") → **reqtītaȥ → reξītaȥ ("they can let me return it")

Voice

Active

Middle

The middle voice (also called the mediopassive voice) is in the middle between the active and the passive voices, as the subject often cannot be categorised as either agent or patient but may have elements of both. The middle voice is usually inherently intransitive, and transitive or ditransitive verbs conjugated into the middle voice usually become intransitive themselves. It is formed by attaching the middle verb endings to the root of a verb.

Uses of the middle voice

The meaning of a verb in the middle voice often depends on the context of the sentence and the lexical properties of the word itself. In its most basic sense, it may be used simply as a valancy decreasing operation. As transitive verbs require an object in the active voice (because transitive verbs must agree with the object), the middle voice may be used merely to omit an object, to highlight the subject or some other part of the sentence, or to simply make a blanket statement.

- aedaȥ 'they love me' (active) → aedor 'I love' (middle)

- legis 'theyi choose themj' (active) → legerur 'theyj choose' (middle)

Animacy can play a major role in the meaning of a verb in the middle voice. Verbs with more animate subjects, such as people, animals, gods, etc., may be interpreted as more towards an active meaning, whilst less animate subjects, like inanimate objects or possessions, may be interpreted as more passive in meaning.

aug

see

-ērur

-MID.3SG.T

se

this

-us

-T.NOM.SG

ar[d]

wumbo

-s

-NOM.SG

(more animate)

'That wumbo sees'

aug

see

-ērra

-MID.3SG.C

se

this

-a

-C.NOM.SG

salv

book

-a

-NOM.SG

(less animate)

'That book is seen'

Sometimes, it may have a reflexive meaning, or the sense of doing something for ones own benefit.

nesc

wash

-iȥ

-ACT.1SG

vomin

river

-īs

-LOC.SG

(active voice)

'They wash me in a river'

nesc

wash

-or

-MID.1SG

vomin

river

-īs

-LOC.SG

(middle voice)

'I washed (myself) in a river'

hastid

sacrifice

-ēs

-ACT.3SG.T

osc

Oscus

-us

-NOM.SG

abr

fish

-un

-ACC.SG

(active voice)

'Oscus sacrificed a fish'

hastid

sacrifice

-ērur

-MID.3SG.T

osc

Oscus

-us

-NOM.SG

abr

fish

-ōrun

-INSTR.SG

(middle voice)

'Oscus sacrificed a fish (for their benefit)'

Another important use of the middle voice is the experiential middle voice. When used with sensory verbs the middle voice may be used to differentiate experiential, nonvolitional sensation (see, hear, smell, feel, know, etc.), as opposed to active, volitional sensation (look, listen, sniff, touch, understand, etc.) Often times, the object of the sensory verb will be expressed using an oblique case, usually the ablative.

īd

hear/listen

-ēs

-ACT.3SG.T

=te

=1SG.NOM

pon

voice

-un

-ACC.SG

garīn

friend

-ī

-GEN.SG

gellē

happily

(active voice)

'I like to listen to (my) friend's voice'

īd

hear/listen

-eor

-MID.1SG

pon

voice

-ā

-ABL.SG

garīn

friend

-ī

-GEN.SG

gellē

happily

(middle voice)

'I like to hear (my) friend's voice'

Passive

The passive voice in Aeranir shares many traits with the middle voice, and often times the distinction between the two can be subtle, nuanced, or obscure. The passive was rare in Old Aeranir and even in the Classical period remained unusual, with the middle voice still preferred for passive clauses. It only began to rise in popularity in Late Aeranir. In its most basic form, the grammatical subject (nominative argument) expresses the theme or patient of the main verb – that is, the person or thing that undergoes the action or has its state changed. This is opposed to the active voice, where the nominative argument expresses the agent of a transitive clause or subject of an intransitive one, and the middle voice, which has traits of both.

Uses of the passive

Unlike the middle voice, the passive is not used for verbal complements, and it cannot take the agent of a verb as its subject. It is never used in verbal complements.

tet

drink

-erur

-MID.3SG.E

se

this

-un

-E.NOM.SG

tīn

tea

-Ø

-NOM.SG

iūs

well

'This tea tastes good (lit. 'it drinks well').'

tet

drink

-ēlārur

-PAS.3SG.E

se

this

-un

-E.NOM.SG

tīn

tea

-Ø

-NOM.SG

iūs

well

'This tea is drunk often.'

While the agent may be dropped in a passive clause, it may also be included, using the ablative case.

praescend

rebuild

-uēlāre

-PFV.PAS.3SG.E

ūl

yonder

-un

-E.NOM.SG

cav

Cava

-ā

-ABL.SG

īliān

Ilianus

-ā

-C.ABL.SG

hān

temple

-un

-NOM.SG

'This temple was rebuilt by Cava Iliana.'

The passive can also be especially with intransitive verbs to form denote an unspecified/generic subject. This structure may is used to make general statements or observations. Negation for this type uses mū.

miqu

die

-ītur

-MID.3PL.T

'They are dead/dying.'

miqu

die

-iēlātur

-PAS.3PL.T

'There are people dead/dying.'

mūδ

not.enough

-erra

-MID.3SG.C

(se

(this

-a)

-C.NOM.SG)

ard

wumbo

-ina

-DAT.PL

inder

capital

-is

-GEN.SG

alt

water

-a

-NOM.SG

'This is not enough water for the people of the capital.'

mūδ

not.enough

-ēlārra

-PAS.3SG.C

ard

wumbo

-ina

-DAT.PL

inder

capital

-is

-GEN.SG

alt

water

-a

-NOM.SG

'There is not enough water for the people of the capital.'

Similarly, the passive can be used to form the aversive passive, denoting an undesirable even or outcome.

cōmer

home

-ī

-DAT

requ

return

-ent

-IPFV.PTCP

-us

-T.NOM.SG

fur

fall

-uēlō

-PFV.PAS.1SG

soper

snow

-ī

-ABL.SG

'Walking home I got snowed on.'