User:Chrysophylax/Creating an Indo-European Conlang: Difference between revisions

Chrysophylax (talk | contribs) |

Tag: Undo |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

The family is also one of the largest language family in the world in terms of native speakers. Languages as different as English (365 million), Latin (few to none), Ancient Greek (few to none), Hindi-Urdu(361 million), Russian (162 million), Welsh (720,000), and Armenian (6 million) all belong to this gigantic, sprawling family. | The family is also one of the largest language family in the world in terms of native speakers. Languages as different as English (365 million), Latin (few to none), Ancient Greek (few to none), Hindi-Urdu(361 million), Russian (162 million), Welsh (720,000), and Armenian (6 million) all belong to this gigantic, sprawling family. | ||

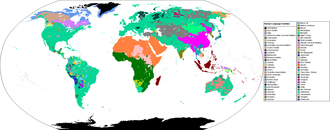

[[File:Primary Human Language Families Map.png|thumbnail| | [[File:Primary Human Language Families Map.png|thumbnail|Distribution of the world's language families with Indo-European in cyan]] | ||

All in all, Indo-European languages offer the conlanger ample material from which to draw upon when engaging in lighthearted linguogenesis, what with detailed grammars, lexica, recordings, dissertations, and so on. Whether it be [[Aarlaansk]] (a descendant of Latin in northwestern Europe), [[Harākti]] (a sibling of Hittite), '''Gutiskar''' (Germanic), '''Syrunian''' (a Levantine descendant of Latin), '''Thorian''' (a close relative of the Greek family), '''Quadian''' (an 'old Germanic' language) or belonging to a whole new branch entirely as '''Alkalic''', '''Nṛtranya''' (a language drawn from a 'reconstructed PIE'-lexicon based on mostly Proto-Germanic words then taken down through Sanskrit-y sound changes) or [[Dhannuá]] (a melangemischung of Celtic, Italic, and Germanic elements), Indo-European-derived languages don't seem to be ceasing in popularity or creativity any time soon. | All in all, Indo-European languages offer the conlanger ample material from which to draw upon when engaging in lighthearted linguogenesis, what with detailed grammars, lexica, recordings, dissertations, and so on. Whether it be [[Aarlaansk]] (a descendant of Latin in northwestern Europe), [[Harākti]] (a sibling of Hittite), '''Gutiskar''' (Germanic), '''Syrunian''' (a Levantine descendant of Latin), '''Thorian''' (a close relative of the Greek family), '''Quadian''' (an 'old Germanic' language) or belonging to a whole new branch entirely as '''Alkalic''', '''Nṛtranya''' (a language drawn from a 'reconstructed PIE'-lexicon based on mostly Proto-Germanic words then taken down through Sanskrit-y sound changes) or [[Dhannuá]] (a melangemischung of Celtic, Italic, and Germanic elements), Indo-European-derived languages don't seem to be ceasing in popularity or creativity any time soon. | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

#Recommended introductory reading | #Recommended introductory reading | ||

::* [[ | ::* [[wikipedia:Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European language]] at Wikipedia | ||

::* Donald Ringe's ''From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic'' (2006), ISBN 9780199284139 | ::* Donald Ringe's ''From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic'' (2006), ISBN 9780199284139 | ||

::* Mallory, JP; Adams, DQ ''The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World'' (2006), ISBN 9780199296682 | ::* Mallory, JP; Adams, DQ ''The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World'' (2006), ISBN 9780199296682 | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

If you find that making romlangs, germlangs, slavlangs, sinolangs, celtlangs just a bit too constraining, the option of making up your own base on which to experiment further on is a safe bet for fun! The reasons for engaging in diachronic conlanging with PIE as point of origin are many and varied - just like the results. By building your own branch of the Indo-European tree you'll have lots of exciting moments dealing with concepts like common innovations, isoglosses, borrowings, conservatism-innovation, and so on. | If you find that making romlangs, germlangs, slavlangs, sinolangs, celtlangs just a bit too constraining, the option of making up your own base on which to experiment further on is a safe bet for fun! The reasons for engaging in diachronic conlanging with PIE as point of origin are many and varied - just like the results. By building your own branch of the Indo-European tree you'll have lots of exciting moments dealing with concepts like common innovations, isoglosses, borrowings, conservatism-innovation, and so on. | ||

This chapter assumes a basic understanding of concepts such as [[ | This chapter assumes a basic understanding of concepts such as [[wikipedia:phoneme|phoneme]], [[wikipedia:allophone|allophone]], [[wikipedia:Ablaut|ablaut]], [[wikipedia:Word order|word order]], and so on. | ||

===The processes of change and their effects=== | ===The processes of change and their effects=== | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

===Forging a phonology=== | ===Forging a phonology=== | ||

Proto-Indo-European is commonly accepted to have had the following vowel and consonant inventory | Proto-Indo-European is commonly accepted to have had the following vowel and consonant inventory with some minor disagreements on the phonemicity of *a | ||

{| class="greentable" | {| class="greentable" | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

|- | |- | ||

!rowspan="2" colspan="2"| | !rowspan="2" colspan="2"| | ||

!rowspan="2"|[[ | !rowspan="2"|[[wikipedia:labial consonant|Labial]] | ||

!rowspan="2"|[[ | !rowspan="2"|[[wikipedia:coronal consonant|Coronal]] | ||

!colspan="3"|[[ | !colspan="3"|[[wikipedia:dorsal consonant|Dorsal]] | ||

!rowspan="2"|[[ | !rowspan="2"|[[wikipedia:Laryngeal theory|Laryngeal]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

!<small>palatal</small> | !<small>palatal</small> | ||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

!<small>labial</small> | !<small>labial</small> | ||

|- | |- | ||

!colspan="2"|[[ | !colspan="2"|[[wikipedia:Nasal stop|Nasal]] | ||

| align=center | *{{PIE|m}} | | align=center | *{{PIE|m}} | ||

| align=center | *{{PIE|n}} | | align=center | *{{PIE|n}} | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

!rowspan="3"|[[ | !rowspan="3"|[[wikipedia:Plosive consonant|Plosive]] ||<small> | ||

[[ | [[wikipedia:Voiceless consonant|voiceless]]</small> | ||

| align=center | *{{PIE|p}} | | align=center | *{{PIE|p}} | ||

| align=center | *{{PIE|t}} | | align=center | *{{PIE|t}} | ||

| Line 77: | Line 77: | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

!<small>[[ | !<small>[[wikipedia:Voiced consonant|voiced]]</small> | ||

| align=center | (*{{PIE|b}}) | | align=center | (*{{PIE|b}}) | ||

| align=center | *{{PIE|d}} | | align=center | *{{PIE|d}} | ||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

!<small>[[ | !<small>[[wikipedia:aspiration (phonetics)|aspirated]]</small> | ||

| align=center | *{{PIE|bʰ}} | | align=center | *{{PIE|bʰ}} | ||

| align=center | *{{PIE|dʰ}} | | align=center | *{{PIE|dʰ}} | ||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

!colspan="2"|[[ | !colspan="2"|[[wikipedia:fricative consonant|Fricative]] | ||

| | | | ||

| align=center | *{{PIE|s}} | | align=center | *{{PIE|s}} | ||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

| align=center | {{PIE|*h₁, *h₂, *h₃}} | | align=center | {{PIE|*h₁, *h₂, *h₃}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

!colspan="2"|[[ | !colspan="2"|[[wikipedia:liquid consonant|Liquid]] | ||

| | | | ||

| align=center | {{PIE|*r, *l}} | | align=center | {{PIE|*r, *l}} | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

!colspan="2"|[[ | !colspan="2"|[[wikipedia:Approximant|Approximant]] | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

| | | | ||

|} | |} | ||

You have many options available in the treatment of the vowels and consonants; already in Proto-Indo-European we discern a trend towards either engaging in af/fricativisation or not of the 'palatovelars'. This important isogloss divides Indo-European into two broad swaths: Centum and Satem. Cf. | {| class="greentable" | ||

|+ '''PIE vowels''' | |||

! rowspan=1| | |||

! colspan=1| [[w:Front vowel|Front]] | |||

! colspan=1| [[w:Back vowel|Back]] | |||

|- align=center | |||

! [[w:Close vowel|Close]] | |||

| *{{PIE|i}} | |||

| *{{PIE|u}} | |||

|- align=center | |||

! [[w:Mid vowel|Mid]] | |||

| *{{PIE|e}} *{{PIE|ē}} | |||

| *{{PIE|o}} *{{PIE|ō}} | |||

|- align=center | |||

! [[w:Open vowel|Open]] | |||

| a* ā* | |||

| | |||

|} | |||

You have many options available in the treatment of the vowels and consonants; already in Proto-Indo-European we discern a trend towards either engaging in af/fricativisation or not of the 'palatovelars'. This important isogloss divides Indo-European into two broad swaths: Centum and Satem. Cf. reconstructed PIE [[wikt:Appendix:Proto-Indo-European/ḱm̥tóm#Proto-Indo-European|*(d)ḱm̥tóm]] and its descendants [[wikt:centum#Latin|centum (Latin)]] & [[wikt:शत#Sanskrit|śatá (Sanskrit)]]. | |||

===Melting morphology=== | ===Melting morphology=== | ||

While Proto-Indo-European is reconstructed as having a somewhat complex morphology both for nouns and verbs, almost all descendants strongly simplified the systems. | |||

===Smithing smooth sentences syntactically=== | ===Smithing smooth sentences syntactically=== | ||

| Line 128: | Line 147: | ||

==Creating a descendant of a modern language chapter== | ==Creating a descendant of a modern language chapter== | ||

<!--My contribewshins [[User:Ceige|Ceige]] ([[User talk:Ceige|talk]]) 11:16, 3 February 2014 (CET) --> | |||

===Step Vån: Becoming the Farseer=== | |||

''Or the prophet, depending on your belief system. Or a Jedi, depending on your fandom.'' | |||

Creating a descendant of a modern language almost always involves predicting the future to whatever degree. Sometimes, this is less pronounced, especially if your goal is to imagine English if Japan took over the United States of America, in which case, while you can still play the prophet, there's less of a need since you're knee-deep in fantasy as is. | |||

Another factor is time. How far in the future is your descendent? Is it English spoken in 100 years in New Zealand (New Zullunish, presumably), or is it English spoken in the year 4320, after assimilating Chilean Spanish and Palestinian Arabic into it, on the planet El-Kzæm? The further ahead in the future, the more liberal your changes can be, but you'll still have to pay attention to what you're doing to make things neat - it's just a slightly different focus though, with more creative freedom, as you can now say, for example, that -në is the English genitive ending, and make up a long and twisted tale explaining this. | |||

When your language is only 230 years different from its ancestor, though, it becomes harder to explain how English adopted the Russian -skaya adjective ending as a perfect verb marker. | |||

===Step Tøui: Peering into the Crystal Ball=== | |||

''... and which brand of protective goggles will give you the best run for your money.'' | |||

Now that you're thinking like a fortune teller, a wizard, or an ethically-challenging supercomputer given more control of human life than is safe, it's time to thing about your focus. | |||

* Younger languages generally require more thought about phonology, vocabulary and style, and ''then'' the results on grammar. | |||

* Older languages generally require a goal to work towards - e.g. make a change to the language, and ''then'' explain it and see if it fits. | |||

...''however'', that said, you can use either method for either language. There's no strict rules, they're purely recommmendations to help make things more efficient. For example, making an older language using the guide for younger languages could take you on a very long journey where you might lose your place. You might want that, actually. With younger languages, you might have a specific goal, and find it easier to explain changes away after you've made them - but this might get unrealistic fast (for example, South Australian English /fa:st/ isn't going to turn into /hi:çþ/ overnight without a ''very'' good explanation). | |||

===Step Frei: Interpreting the Visions=== | |||

''"In 5 years time, I see you as a generous fisherman - oh, wait, I meant I see you getting eaten by a shark and having your house looted, mah bad!"'' | |||

You want to know the context of your future language, both the things that you want to be in the context, and things that should naturally be part of the context. | |||

For example: Spanish in North America in the year 2200AD (SpanNA), during the reign of Immortal Overlord Obama. | |||

What do we want? | |||

* Spanish 200 years later | |||

* Probably some English influence on vocabulary and grammar too | |||

What do we need to keep in mind? | |||

* Will English influence SpanNA's phonology? | |||

** On a similar note, how will English evolve phonologically over that 200 years, and how will it influence SpanNA? | |||

* What sort of community is it? | |||

** Are they open to learners? (affects purity) | |||

** Are they monolingual, bilingual, trilingual? Do they codeswitch a lot? (affects purity) | |||

** Do they see their own language as a standard, or do they consider another variety of Spanish as "correct"? (affects whether the language follows after another related one, or looks for its own identity) | |||

... and so on. | |||

Basically, you want to make sure that the future you're seeing is complete and internally rather consistent with what you want. Injecting fantasy to oil the gears of creativity is OK, but even good fantasy tales need consistency! | |||

====Semistep Frei-poñt-vån: Don't worry, everyone goes through this stage!==== | |||

''うそだよ'' | |||

Here's some common things that can affect any language, for any number of reasons (half the fun is pretending you know why!): | |||

* [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenition Lenition] and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fortition Fortition]. Lenition is why we say "three" in English instead of "tree". Fortition is why Germans say "drei" instead of "threi". On the other hand, '''fortition ''then'' lenition''' is why Germans say "Wasser" instead of "Water". | |||

* Vowel changes, such as [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_phonology#Devoicing devoicing], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Vowel_Shift diphthongisation] and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vowel_harmony vowel harmony]. | |||

* [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_language Palatalisation] and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_Arrernte_language#Phonology Labialisation] | |||

* A combination of some or all of the above, such as in French, German and Irish. | |||

===Step Fwå: Comparing Ancestor with Descendent=== | |||

''AKA when you find out that your Chihuahua is possessed by your great grandfather's vengeful spirit.'' | |||

A good step towards finding a codified version of your dream descendant language is to compare what you have so far with the original language via translating passages from it. A quick ad hoc example: | |||

: English (normal): ''Today I had eggs and ham on my pizza. It was amazing.'' | |||

: English (hypothetical descendent): ''Tsdää, åå dån hev jeg ån hem on måå petsa. Ben määz'' | |||

From this, I can compare all the changes from the original language word by word, see how it all flows together, see if I've accidentally missed something or converted a word wrongly (irregularities are fine as long as you're happy with justifying them), and ultimately I can make sure I can appreciate the evolution that's taken place. | |||

==Chapter on sibling-makery, e.g., Harākti== | ==Chapter on sibling-makery, e.g., Harākti== | ||

[[Category:Guides]] | [[Category:Guides]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:30, 13 August 2020

| ||||||||||||||

Foreword

The moniker “Indo-European languages” represent one of the most studied (if not the most) language families of the world; quite a few of history's great cultural hegemons have been part of this family, a fact which is most storngly noticed when one surveys the amount of research.

The family is also one of the largest language family in the world in terms of native speakers. Languages as different as English (365 million), Latin (few to none), Ancient Greek (few to none), Hindi-Urdu(361 million), Russian (162 million), Welsh (720,000), and Armenian (6 million) all belong to this gigantic, sprawling family.

All in all, Indo-European languages offer the conlanger ample material from which to draw upon when engaging in lighthearted linguogenesis, what with detailed grammars, lexica, recordings, dissertations, and so on. Whether it be Aarlaansk (a descendant of Latin in northwestern Europe), Harākti (a sibling of Hittite), Gutiskar (Germanic), Syrunian (a Levantine descendant of Latin), Thorian (a close relative of the Greek family), Quadian (an 'old Germanic' language) or belonging to a whole new branch entirely as Alkalic, Nṛtranya (a language drawn from a 'reconstructed PIE'-lexicon based on mostly Proto-Germanic words then taken down through Sanskrit-y sound changes) or Dhannuá (a melangemischung of Celtic, Italic, and Germanic elements), Indo-European-derived languages don't seem to be ceasing in popularity or creativity any time soon.

As the Indo-European family has an abundance of material written on it, while making the task easier for the conlanger when it comes to deriving new words, it also enforces a modicum of accountability; the Indo-European topic-focus conlang, while completely plausible, sure does have some explaining to do. Basically, it's a lot harder to just make things up out of thin air. On the other hand, you are presented with a wealth of already existing linguistic resources with which to play; a prefabricated sandbox of joy; a themed linguistic LEGO® set with hundreds of manuals and configurations available that resonate across continents.

It is useful to read some literature on the Indo-European family and its reconstructed last common ancestor Proto-Indo-European (commonly referred to as PIE). By reading about the proto-language one comes to a greater understanding of many irregularities in the modern descendants. E.g., English's “difficult” strong verbs: sing, sang, sung; spring, sprang, sprung; give, gave, given, or Latin's rare reduplicating verbs, e.g., disco, didici ; tango, tetigi. Not only are these processes all understandable when viewed from an Indo-European point of view; they also provide lots of ideas for the conlanger!

While ultimately not 'super' necessary for the conlanger who's creating a descendant of Modern English as spoken by a mix of Ameri-Russo-Japanese space explorers 200 years from now on the moon of Titan, it is quite useful to familiarise oneself with many of the concepts discussed in Indo-European linguistics when guiding conlangs through a linguistic conhistory.

- Recommended introductory reading

- Proto-Indo-European language at Wikipedia

- Donald Ringe's From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (2006), ISBN 9780199284139

- Mallory, JP; Adams, DQ The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (2006), ISBN 9780199296682

- Various books on Proto-Indo-European with "introduction" in their titles.

As you familiarise yourself more and more with the Indo-European languages, you start stumbling onto a few questions regarding your conlang — do I want my own branch? my own descendant of an already existing branch? a contact language between two branches? a descendant of a specific language? — these are all valid questions and options available to you when crafting it.

When creating a descendant, looking at how the language you're basing your conlang on developed compared to its siblings can be a helpful exercise in determining general trends and may even spark some ideas for your own language!

On the other hand, if you choose to innovate a whole new language based on PIE itself you have a the delightful task of deciding in which direction to take it. Again, reviewing languages you personally enjoy and their history can be quite a powerful tool when it comes to ideogenesis.

If you feel like joining la grande famille in terms of both nat- and conlangs, you've stumbled onto the right place,

— User:Chrysophylax, editor.

nota bene: this page is a living document and is prone to sudden changes at any time. If you wish to find a previous version, please use the history tab. When linking to people outside of the wiki, it is recommended that you link directly to the version you are seeing as the state of the document cannot be guaranteed for the future.

A whole new world: creating your own PIE-derived language

If you find that making romlangs, germlangs, slavlangs, sinolangs, celtlangs just a bit too constraining, the option of making up your own base on which to experiment further on is a safe bet for fun! The reasons for engaging in diachronic conlanging with PIE as point of origin are many and varied - just like the results. By building your own branch of the Indo-European tree you'll have lots of exciting moments dealing with concepts like common innovations, isoglosses, borrowings, conservatism-innovation, and so on.

This chapter assumes a basic understanding of concepts such as phoneme, allophone, ablaut, word order, and so on.

The processes of change and their effects

The primary driving force of linguistic change is […] […]these interact in many ways making […] In the next three parts we will discuss them separately […]

Forging a phonology

Proto-Indo-European is commonly accepted to have had the following vowel and consonant inventory with some minor disagreements on the phonemicity of *a

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Laryngeal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| palatal | plain | labial | |||||

| Nasal | *m | *n | |||||

| Plosive | *p | *t | *ḱ | *k | *kʷ | ||

| voiced | (*b) | *d | *ǵ | *g | *gʷ | ||

| aspirated | *bʰ | *dʰ | *ǵʰ | *gʰ | *gʷʰ | ||

| Fricative | *s | *h₁, *h₂, *h₃ | |||||

| Liquid | *r, *l | ||||||

| Approximant | *y [j] | *w | |||||

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | *i | *u |

| Mid | *e *ē | *o *ō |

| Open | a* ā* |

You have many options available in the treatment of the vowels and consonants; already in Proto-Indo-European we discern a trend towards either engaging in af/fricativisation or not of the 'palatovelars'. This important isogloss divides Indo-European into two broad swaths: Centum and Satem. Cf. reconstructed PIE *(d)ḱm̥tóm and its descendants centum (Latin) & śatá (Sanskrit).

Melting morphology

While Proto-Indo-European is reconstructed as having a somewhat complex morphology both for nouns and verbs, almost all descendants strongly simplified the systems.

Smithing smooth sentences syntactically

Loaning lexica - word borrowing between PIE dialects

Differentiation - ideas for creating siblings

Creating a descendant of a modern language chapter

Step Vån: Becoming the Farseer

Or the prophet, depending on your belief system. Or a Jedi, depending on your fandom.

Creating a descendant of a modern language almost always involves predicting the future to whatever degree. Sometimes, this is less pronounced, especially if your goal is to imagine English if Japan took over the United States of America, in which case, while you can still play the prophet, there's less of a need since you're knee-deep in fantasy as is.

Another factor is time. How far in the future is your descendent? Is it English spoken in 100 years in New Zealand (New Zullunish, presumably), or is it English spoken in the year 4320, after assimilating Chilean Spanish and Palestinian Arabic into it, on the planet El-Kzæm? The further ahead in the future, the more liberal your changes can be, but you'll still have to pay attention to what you're doing to make things neat - it's just a slightly different focus though, with more creative freedom, as you can now say, for example, that -në is the English genitive ending, and make up a long and twisted tale explaining this.

When your language is only 230 years different from its ancestor, though, it becomes harder to explain how English adopted the Russian -skaya adjective ending as a perfect verb marker.

Step Tøui: Peering into the Crystal Ball

... and which brand of protective goggles will give you the best run for your money.

Now that you're thinking like a fortune teller, a wizard, or an ethically-challenging supercomputer given more control of human life than is safe, it's time to thing about your focus.

- Younger languages generally require more thought about phonology, vocabulary and style, and then the results on grammar.

- Older languages generally require a goal to work towards - e.g. make a change to the language, and then explain it and see if it fits.

...however, that said, you can use either method for either language. There's no strict rules, they're purely recommmendations to help make things more efficient. For example, making an older language using the guide for younger languages could take you on a very long journey where you might lose your place. You might want that, actually. With younger languages, you might have a specific goal, and find it easier to explain changes away after you've made them - but this might get unrealistic fast (for example, South Australian English /fa:st/ isn't going to turn into /hi:çþ/ overnight without a very good explanation).

Step Frei: Interpreting the Visions

"In 5 years time, I see you as a generous fisherman - oh, wait, I meant I see you getting eaten by a shark and having your house looted, mah bad!"

You want to know the context of your future language, both the things that you want to be in the context, and things that should naturally be part of the context.

For example: Spanish in North America in the year 2200AD (SpanNA), during the reign of Immortal Overlord Obama. What do we want?

- Spanish 200 years later

- Probably some English influence on vocabulary and grammar too

What do we need to keep in mind?

- Will English influence SpanNA's phonology?

- On a similar note, how will English evolve phonologically over that 200 years, and how will it influence SpanNA?

- What sort of community is it?

- Are they open to learners? (affects purity)

- Are they monolingual, bilingual, trilingual? Do they codeswitch a lot? (affects purity)

- Do they see their own language as a standard, or do they consider another variety of Spanish as "correct"? (affects whether the language follows after another related one, or looks for its own identity)

... and so on.

Basically, you want to make sure that the future you're seeing is complete and internally rather consistent with what you want. Injecting fantasy to oil the gears of creativity is OK, but even good fantasy tales need consistency!

Semistep Frei-poñt-vån: Don't worry, everyone goes through this stage!

うそだよ

Here's some common things that can affect any language, for any number of reasons (half the fun is pretending you know why!):

- Lenition and Fortition. Lenition is why we say "three" in English instead of "tree". Fortition is why Germans say "drei" instead of "threi". On the other hand, fortition then lenition is why Germans say "Wasser" instead of "Water".

- Vowel changes, such as devoicing, diphthongisation and vowel harmony.

- Palatalisation and Labialisation

- A combination of some or all of the above, such as in French, German and Irish.

Step Fwå: Comparing Ancestor with Descendent

AKA when you find out that your Chihuahua is possessed by your great grandfather's vengeful spirit.

A good step towards finding a codified version of your dream descendant language is to compare what you have so far with the original language via translating passages from it. A quick ad hoc example:

- English (normal): Today I had eggs and ham on my pizza. It was amazing.

- English (hypothetical descendent): Tsdää, åå dån hev jeg ån hem on måå petsa. Ben määz

From this, I can compare all the changes from the original language word by word, see how it all flows together, see if I've accidentally missed something or converted a word wrongly (irregularities are fine as long as you're happy with justifying them), and ultimately I can make sure I can appreciate the evolution that's taken place.