Ris: Difference between revisions

| Line 607: | Line 607: | ||

{{Gloss | {{Gloss | ||

|phrase = | |phrase = thuo trema | ||

|IPA = / | |IPA = /ˈtʰʉ̩ːɔ ˈtreːma/ | ||

|morphemes = | |morphemes = thu-o tre-{{blue|ma}} | ||

|gloss = to want-IND.PRFV.1.SG.M wheat.IV-{{blue|PAT}}.SG | |gloss = to want-IND.PRFV.1.SG.M wheat.IV-{{blue|PAT}}.SG | ||

|translation = I want a grain of wheat. | |translation = I want a grain of wheat. | ||

| Line 615: | Line 615: | ||

{{Gloss | {{Gloss | ||

|phrase = | |phrase = mnio mna koupar | ||

|IPA = /ˈmnɪ̩ːɔ | |IPA = /ˈmnɪ̩ːɔ mna ˈkʊːpar/ | ||

|morphemes = | |morphemes = mni-o mna koupar-{{blue|∅}} | ||

|gloss = to see-IND.PRFV.1.SG.M ram.I.{{blue|PAT}}.SG | |gloss = to see-IND.PRFV.1.SG.M one ram.I.{{blue|PAT}}.SG | ||

|translation = I see a ram. | |translation = I see a ram. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 624: | Line 624: | ||

{{Gloss | {{Gloss | ||

|phrase = imbrouas pagma? | |phrase = imbrouas pagma? | ||

|IPA = / | |IPA = /ˈɪːmpʼrwas ˈpaːkma/ | ||

| morphemes = im-rou-as pag-{{blue|ma}} | | morphemes = im-rou-as pag-{{blue|ma}} | ||

| gloss = to hold-SUBJ.PRFV-2.SG.M time.IV-{{blue|PAT}}.SG | | gloss = to hold-SUBJ.PRFV-2.SG.M time.IV-{{blue|PAT}}.SG | ||

Revision as of 19:09, 23 October 2013

This article is a construction site. This project is currently undergoing significant construction and/or revamp. By all means, take a look around, thank you. |

| Ris | |

|---|---|

| Rhánzi ris | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [/ˈr̥ʰand͡z͎ɪ rɪs͎/] |

| Created by | – |

| Native to | Italy, Cyprus; Sicily |

| Native speakers | 301,486 (2012) |

Menmer languages

| |

Early form | Proto-Men

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ri |

| ISO 639-2 | ri |

| ISO 639-3 | qri |

Ris is my attempt to unite the sketchy constructed languages of mine; those lost forever in incomprehensible grammar, unsatisfying aesthetics and cumbersome phonologies. They stand united by the one shared feature - their relationship to the Greek language; my greatest influence no matter the language.

The Ris language, ῤανζι ρις /r̥ʰand͡z͎ɪ rɪs͎/, is a language isolate, and is thus not known to be related to any extant language. Ris has a normal-sized inventory of consonants and a fair amount of allophony. It is a fusional language and is morphosyntactically active-stative and with a fluid subject. The morphology is evenly split between nominal and verbal inflections.

Information

The Ris language, ῤανζι ρις /r̥ʰand͡z͎ɪ rɪs͎/, is a constructed language, but does have a fictional background set in the real world. It is spoken on Sicily and on Cyprus and has about 300,000 native speakers. Or 1. Depends on how you count.

Grammatically speaking, the Ris language is morphologically fusional with a few agglutinative characteristics. It has enclitic pronouns representing the core arguments of agent and patient.

It also has an unsusual morphosyntactic alignment; the active-stative one, in the fluid subject subtype. This implies a system of control and volition, closely tied to a distinction in animacy.

Phonologically and phonaesthetically, the language is modelled after Greek. Other influences are native American languages, the Shona language and to certain degree Swedish.

Phonology

Consonants

The following is the inventory of consonants in the Ris language. There are 18 contrastive consonants.

| Consonants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Denti-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||

| plain | apical | |||||||

| Nasals | plain | m /m/ | n /n/ | [ŋ] | ||||

| Plosives | aspirated | bh /pʰ/ | th /tʰ/ | kh /kʰ/ | [ʔ] | |||

| unvoiced | p /p/ | t /t/ | k /k/ | |||||

| ejective | b /pʼ/ | d /tʼ/ | g /kʼ/ | |||||

| Fricatives | unvoiced | s /s ~ s̺/ | h /ç ~ x ~ h/ | |||||

| voiced | z /d͡z ~ d͡z̺ ~ z̺ ~ z̺/ | [ʝ] | ||||||

| Trills | aspirated | r /r̥ʰ/ | ||||||

| voiced | r /r/ | |||||||

| Approximants | ou, u /w/ | i /j/ | ||||||

| Laterals | l /ʎ/ | |||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Ris |

|---|

|

| Main |

| Vocabulary |

| Contionary |

| IPA |

|

Waahlis |

Consonant allophony

Allophony is common to many consonants, and sandhi forces them to be realised different in different environments.

The glottal fricative

The phoneme /h/, the so called glottal fricative, is in free variation with the unvoiced palatal fricative /ç/ as well as the unvoiced velar fricative /x/.

| ἒντρο | ||||

| hentro | ||||

| /ˈhɛntrɔ/ | = | /ˈxɛntrɔ/ | = | /ˈçɛntrɔ/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am normal, okay | ||||

The velar fricative is the most common one, but the phones are all affected by palatalisation from front vowels, producing the palatal fricative [ç].

| ὐο | ἠστιμι | |||||

| hyo | héstimi | |||||

| /ˈhʉ̩.ɔ/ | = | [ˈhʉ̩.ɔ] | /ˈheːs͎tɪmɪ/ | → | [ˈçeːs͎tɪmɪ] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to leave .ind.m. | pride .f | |||||

Palatalisation

Palatalisation applies to velar consonants and occurs due to two main factors:

- Internally: Front vowels and the palatal approximant, /j/, tend to palatalise preceding consonants if the syllable is stressed.

- C[-pal, +velar] → C[+pal, -velar] / _V[+front, +stress]

- Externally: A final near-close near-front vowel, /ɪ/, palatalises the initial consonant of the following word.

| ρακι | τη | ἠστιμι | τι κατέρριστουας? | |||||||||||

| raki | té | héstimi? | ti katérristouas? | |||||||||||

| /ˈrakɪ/ | → | [ˈracɪ] | /ˈteː/ | → | [ˈteː] | /ˈheːstɪmɪ/ | → | [ˈçeːstɪmɪ] | /ˈtɪ kaˈtɛrrɪstwas/ | → | [ˈtɪ caˈtɛrrɪstwas̟] | |||

| root .in.gen | how | pride. .f.pat | What are you writing? | |||||||||||

Phonological processes

Vowels

There are 7 vowel phonemes in the Ris language. In Ris, the system of vowels are known as ptégna i rhaki - 'the hollow triangle', due to their symmetrical places of articulation.

All vowels may be long, but the phonemes /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ change their quality when long; they are then pronounced /eː/ and /oː/ respectively.

| Front | Near-front | Central | Near-back | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | short | y /ʉ/ | ||||

| long | ý /ʉː/ | |||||

| Near-close | short | i /ɪ/ | ou /ʊ/ | |||

| long | í /ɪː/ | oú /ʊː/ | ||||

| Close-mid | é /eː/ | ó /oː/ | ||||

| Mid | ||||||

| Open-mid | e /ɛ/ | o /ɔ/ | ||||

| Near-open | ||||||

| Open | short | a /ä/ | ||||

| long | á /äː/ | |||||

Other than that, my vowels are rather simple. No mystics quirks at all. Well, that's if you choose to ignore the vowel harmony and umlaut process in the Damian dialect. Makes it a tad more interesting, in my opinion.

Orthography

Ris is primarily written in the Latin alphabet, but the original alphabet was in fact Greek. In its classical and modern form, the alphabet has 24 letters, ordered from alpha to omega; or ai mḗ otḗma in Ris. The below table shows the two alphabets and the Ris names for the letters, as well as the pronunciation in Standard Ris and the colloquial Ouis dialect.

| Orthography | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek | Latin | Pronunciation | |||

| Ris | Ouis | ||||

| Α α | άλπα | A a | ai | /a/ | |

| Β β | βήτα | B b | bou | /b/ | /β/ |

| Γ γ | γάμμα | G g | gou | /g/ | /ɣ/ |

| Δ δ | δέλτα | D d | da | /d/ | /ð/ |

| Ε ε | έψιλαν | E e | egnás | /ɛ/ | |

| Ζ ζ | ζήτα | Z z | za | /d͡z ~ d͡z͎ ~ z ~ z͎/ | |

| Η η | ήτα | Ē ē | etḗma | /eː/ | /eɪ̯/ |

| Θ θ | θήτα | Th th | tha | /tʰ/ | /θ/ |

| Ι ι | ιότα | I i | iou | /ɪ/ | |

| Κ κ | κάππα | K k | kau | /k/ | |

| Λ λ | λάπτα | L l | la | /l/ | |

| Μ μ | μύα | M m | ḗma | /m/ | |

| Ν ν | νύα | N n | ḗna | /n/ | |

| Ξ ξ | ξία | X x | ḗxa | /ks͎ ~ gz͎/ | |

| Ο ο | ομίκραν | O o | ognás | /ɔ/ | |

| Π π | πία | P p | pau | /p/ | |

| Ρ ρ | ρό | R r | ría | /r/ | /ɹ/ |

| 'Ρ ῤ | ῤαυ | Rh rh | rhau | /r̥ʰ/ | /r/ |

| Σ σ ς | σίγμα | S s | sa | /s͎/ | |

| Τ τ | τάυ | T t | tau | /t/ | |

| Υ υ | ύψιλαν | Y y | hytḗma | /ʉ/ | /ʏ/ |

| Φ φ | φία | Ph ph | pha | /pʰ/ | /f/ |

| Χ χ | χία | Kh kh | kha | /kʰ/ | /x/ |

| Ψ ψ | ψία | Ps ps | ḗpsa | /ps͎/ | |

| Ω ω | ώμεγα | Ō ō | otḗma | /oː/ | /oɪ̯/ |

Diacritics

The Ris alphabets, both the Latin and Greek one, use a few different diacritics to modify the pronunciation. There are five diacritics that mark the following:

- A stressed vowel in a syllable.

- A long vowel in a syllable.

- An aspirated vowel; preceded by /h/. Can also mark the phoneme /r̥ʰ/.

- A stressed, aspirated vowel.

- A long, aspirated vowel.

The use of aspiration here does not refer to the co-articulating process, but rather that the vowel is preceded by an /h/, a "glottal fricative".

Stressed vowels

Stressed vowels are marked with an acute accent, <´>, in the Latin script. In the Greek alphabet, the diacritic is the acute accent as well, only slightly different; <΄>. These mark that the syllable with the vowel is to be stressed, and thus articulated stronger, than other syllables.

| File:Greek acute.png | File:Greek grave.png | File:Latin eta.png |

| Acute | Grave | Eta |

| File:Greek asper.png | File:Greek asper acute.png | File:Latin eta acute.png |

| Spiritus asper | Asper acute | Eta acute |

Long vowels

Long vowels are vowels pronounced vowels articulated for a longer period of time. These get a grave accent in the Greek alphabet, <`>, and a macron in the Latin script, <¯>. Long vowels grave accent in the Greek script when stressed. In the Latin alphabet, however, the stressed long vowels get a second acute accent above the macron, <' ̄́'>.

As previously mentioned, all vowels can be long vowels, but there are two vowels that change their quality when elongated; the /ɛ/ and /ɔ/. These are raised to /eː/ and /oː/ respectively. In the Latin script these are marked as expected, <ē> and <ō>. However, in the Greek script, they are replaced by the letters eta <η> and omega <ω> respectively.

Aspiration

Aspiration, when a vowel is preceded by /h/, is marked by a so-called dasia in the Greek script, <῾>. In the Latin manner of style though, the letter <h> precedes the vowel, as it does phonetically.

In the Greek script, the dasia can be combined with the acute and grave accent, producing <῞> and <῝>.

The dasia can also be placed on the Greek ro sign, <ρ>. The pronunciation of <ῤ> becomes /r̥ʰ/, an aspirated voiceless alveolo-dental trill.

Morphology

- Main article: Ris morphology

Grammar

Number

Ris has three numbers, all of which are equally common in the language. The Ris numbers are different to those of English, instead using a so-called collective-singulative distinction.

The distinction infers that the basic form of a noun is the collective, which is indifferent to the number and unmarked. However, in Ris, the collective form has an additional meaning, and can also signify duals. It is thus the singulative that most often goes unmarked.

Singulative

The singulative (sg) denotes one, single noun, and roughly corresponds to the English equivalent of singular. A singulative noun is a single item, either of a collective noun or even a mass noun.

- thuo trema

/ˈtʰʉ̩ːɔ ˈtreːma/

thu-o tre-ma

to want-IND.PRFV.1.SG.M wheat.IV-PAT.SG

I want a grain of wheat.

- mnio mna koupar

/ˈmnɪ̩ːɔ mna ˈkʊːpar/

mni-o mna koupar-∅

to see-IND.PRFV.1.SG.M one ram.I.PAT.SG

I see a ram.

- imbrouas pagma?

/ˈɪːmpʼrwas ˈpaːkma/

im-rou-as pag-ma

to hold-SUBJ.PRFV-2.SG.M time.IV-PAT.SG

Do you have a minute?

Dual-collective

The dual-collective number (dc) is a special number to the Hrasic language. The dual-collective primarily marks the collective sense, whereas English uses the plural. It does however also signify two nouns, a pair, in certain contexts.

Plurative

The plurative (pl) marks when there are multiple nouns, but more than two. It does not have the collective sense that the English equivalent does.

Gender

There are two genders in the Ris language, the animate (an) and inanimate (inan). The animate gender includes only living animals and insects, as well as supernaturals like spirits and deities. The inanimate gender mainly denotes non-living objects, abstractions as well as flowers and microorganisms.

In the 2nd and 3rd person singular personal pronouns as well as verbs, the animate splits into a feminine (f.an) and masculine (m.an) animate gender. These mark only natural gender.

Morphosyntax

Morphosyntactic alignment and core cases

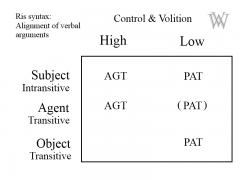

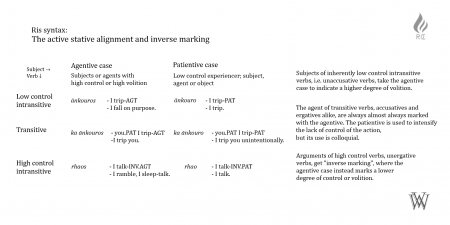

Ris possess an originally active-stative alignment, which means that the two arguments of transitive verbs, the subject and object, are marked with the agentive case and patientive case respectively. The agent of an intransitive verb, however, can be marked with either. The agentive and patientive cases denote a different degree of control and volition with the arguments. Depending on the intransitive verb, different cases would be used.

It later developed the so-called fluid-S subtype, which infers that any intransitive verb can use both the patientive and agentive cases, wich each grant a different degree of control of the verb.

Patientive case

The patientive, or undergoing case, (pat) is the case used to indicate both the subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a transitive verb, in addition to being used for the citation form of nouns.

The patientive is used on low control agents, and experiencers of actions - neither of which have much influence on the verb. Colloquially, the patientive can be used on agents of transitive verbs to indicate a degree of innocence, lack of control of the event.

- Ānkouro.

/ˈaːŋkʊrɔ/

ānkour-∅-o

to trip.ACT-IND.PRFV-PAT.1.SG

I fell.

- Mīthrani hentai inistin.

/ˈmɪːθranɪ ˈçɛntaj ˈɪnɪstɪn/

mīthra-ni in-ist-in

squirrel_soup.III-PAT.DC okay.ADF.PAT exist-ACT-IND.IPFV-3.PAT.DC

Okay squirrel soups exist.

- Tagērras kērax.

/ˈtageːrras ˈkeːraks/

tagēr-r-as kērax-∅

hit.ACT-IMP.PRFV-2.SG.AGT bird.I-PAT.SG

Hit the bird.

- Anēr, ouinēstra teskho...

/ˈaneːr wɪˈneːstra ˈtɛskʰɔ/

anēr-∅ ouinēstra-∅ teskh-∅-o

mother.I-VOC.SG window.II-PAT.SG smash.ACT-IND.PRFV-PAT.1.SG

Mother, I happened to smash the window...

Agentive case

The agentative (agt) case is used to mark the subject, or agent, of transitive verbs. The agentive marks high control, volitional agents of verbs.

- Mau katēro kterma.

/maw kaˈteːrɔ ˈktɛrma/

mau katēr-∅-o kterma-∅

1.AGT.SG writeACT-IND.PRFV-IN.PAT.1.SG letter.III-PAT.SG

I am writing a letter.

- He tethoūris.

/ˈhɛ tɛˈtʰʊːrɪ/

he te~thoūr-is

2.AGT.SG IND.ITR~run.ACT-1.AGT.SG

He is running around.

- Ānkouros...!

/ˈaːŋkʊros/

ānkour-∅-os

trip.ACT-IND.PRFV-AGT.1.SG

I purposely trip...!

Unaccusatives, unergatives and inversion of cases

Not all intransitive verbs are marked as described above. This only applies to Ris unaccusative verbs. The Ris unergative verbs instead inverse the marking, using the agentive as a default, low-control marking, and the patientive for high-control subjects.

An unaccusative verb is a verb that has an experiencer as its subject, that is; the syntactic subject is not a semantic agent. When the subject is marked with the agentive, the agency, control and volition is increased, and it in effect becomes unergative. It gives a sense of intent, and trying.

- Ekrasi mākhina.

/ˈɛkrasːi maːˈkʰɪna/

ekras-∅-i mākhina-∅

crash.ACT-IND.PRFV-PAT.3.SG

The car crashed.

- Anēr psānisti.

/ˈaneːr psaːˈnɪstɪ/

anēr-∅ psān-ist-ɪ

mother.I-PAT.SG cry.ACT-IND.IPVF-PAT.3.SG

Mother cries.

- Ngaos.

/ŋgaˈos/

nga-∅-os

sleep.ACT-IND.PRFV-AGT.1.SG

I am trying to sleep.

Unergatives are intransitive verbs and have a semantic agent as their subject. When the subject is marked with the agentive case, the verb almost unaccusative, lowering the volition, control and agency with the syntactic subject. In the gloss, unergatives have the letters inv} before the casees. Thus, an unergative with a subject in the agentive conveys a feeling of involuntary actions, or trying.

- He gāmi!

/hɛ gaːˈmi/

he gām-∅-i

3.PROX.MA.SG to come.ACT-IND.IMPV-INV.PAT.3.SG

He's coming!

- Antiou rhaistos...

/ˈantjʊ r̥ʰaˈɔs/

anti-ou rha-ist-os

night.IV-LOC.DC talk.ACT-IND.IPVF-INV.AGT.1.SG

I sleep-talk in the night.

- Ti rhās?

/tɪ ˈr̥ʰaːs/

ti rha-∅-as

what.PAT.SG talk.ACT-IND.PRFV-INV.AGT.2.SG

What are you trying to say?

- Kinizas, kinizas!

/kɪnɪˈd͡zas kɪnɪˈd͡zas/

kiniz-∅-as

drive.ACT-IND.PRFV-INV.AGT.2.SG

You're driving, you're driving! (How is it possible?)

Case

There are 7 grammatical cases in Ris. Most of these are rather common to the Indo-European languages.

Instrumental

Instrumental proper

The instrumental (ins) case serves a number of purposes in the Ris language. Primarily, it is used to indicate that a noun is the instrument or means by or with which an action is conducted.

- Thērouna nasērrhan.

/tʰeːˈrʊna naˈseːr̥ʰːan/

thēr-∅-ouna nasēr-rhan

go.ACT-IND.PRFV-AGT.1.SG boat.III-INS.SG

We go by boat.

- Napsantan as...

/naˈpsantan as/

napsa-ntas-n as

learn.ACT-PCP-INS.SG this.PROX.3.SG

By learning this...

- Ankis mia skhasto igan mia.

/ˈancɪs mʊ ˈsxastɔ ˈɪkʼan mʊ/

ankis-∅ mou skha-ist-o i

elbow.III-PAT.DC my.GEN.1.SG scratch.ACT-IND.IPFV-INV.PAT.1.SG nail.II-INS.DC my.GEN.1.SG

I scratch my shoulders with my nails.

Inanimate subjective instrumental

Marking the inanimate noun with the agentive is incorrect. This is a distinction quite well known in natural languages, and even the Proto-Indo-European language is supposed to have made the distinction.

On subject of control in the Ris verbs, inanimate agents of transitive verbs: subjects such as "the knife" in the sentence "The knife slices the bread" could impossibly be marked with the agentive case, since the subject has no control of its actions. Nor is it experiencing the slicing, and can as such not be marked with the patientive. Instead a construction with the mediopassive and instrumental used.

Of course if desired, the agent can be reintroduced, which means a switch from passive to active.

- Lemner me tagī.

/ʎɛmˈnɛr mɛ taˈkʼɪː/

lemn-er me tagi-∅-i

stone.II-AGT.SG me.1.PAT.SG hit.ACT-IND.PRFV-3.AGT.SG

*A stone hit me.

- Entagio lemnanta.

/ˈɛntakʼjɔ ʎɛmˈnanta/

en-tagi-∅-o lemn-anta

MED.hit.IND-PRFV-1.SG.PAT stone.III-INS.PL

I am hit with stones.

- Tagias me lemnanta.

/ˈtakʼjas mɛ ʎɛmˈnanta/

tagi-∅-as me lemn-anta

hit.ACT.IND-PRFV-2.SG.AGT me.1.PAT.SG stone.II-INS.PL

You hit me with stones.

- Kinis lanērrha pāni.

/cɪˈnɪ ʎaˈnɛr̥ʰːa paːˈnɪ/

kin-∅-is lanēr-rha pāni-∅

cut.ACT-IND.PRFV-3.INV.AGT.SG knife.III-AGT.SG bread.III-PAT.SG

*A knife cuts the bread.

- Inkini lanērrhan pāni.

/cɪˈnɪ ʎaˈnɛr̥ʰːan paːˈnɪ/

kin-∅-is lanēr-rhan pāni-∅

MED.cut-IND.PRFV-3.INV.PAT.SG knife.III-INS.SG bread.III-PAT.SG

The bread was cut with a knife.

Comitative instrumental

The Ris instrumental also bears comitative and quantitative senses. It indicates actions in company with other subjects, amounts, as well as lacking things:

- Indroua mena?

/ˈɪndrwa mɛˈna/

in-r-oua me-na

be.ACT-SUBJ.PRFV-2.PAT.SG me.1-INS.SG

Are you with me?

- As arrhos ena.

/as ˈar̥ʰːɔs ɛˈna/

as-∅ arrh-∅-os e-na

it.3.PROX-PAT.SG make.ACT-IND.PRFV-1.AGT.SG s/he.1-INS.SG

I'm making it with him/her. - Ne nenisto na issigan nai.

/nɛ nɛˈnɪstɔ na ˈɪsːɪgan naj/

⟨ne⟩ nen-ist-o ⟨na⟩ issig-an nai

⟨VB.NEG⟩ not_be.ACT-IND.IPFV-1.PAT.SG ⟨VB.NEG⟩ hair.IV-INS.DC NOM.NG

I have no hair / I am not with no hair.

Animate subjective instrumental

The last use of the instrumental, similarly to Russian and in part to English is to reintroduce a subject in a passive clause. The usage is very similar to the adpositional phrase "by me" in English, as in "He was killed", and later; "He was killed by me".

Please note, that this formation, although grammatically correct, is considered quite rude by most speakers. The subjective instrumental is reserved for inanimates for most speakers, and an active verb is used for animate subjects.

- Enmnīnta ouena

/ɛnˈmnɪnta wɛˈna/

en-mnīo-nta oue-na

MED-to_see-PCP 1.EXC-INS.DC

Seen by the two of us.

- Atai eniniskhanta ērrhasterrhan

/ˈataj ɛnɪnɪsˈxanta eːˈr̥ʰːastɛr̥ʰːan/

atai en-ino-iskha-nta ērrho-aster-rhan

they.3.PAT.PL MED-to_be-CAU.CES-PCP to_love-AG-INS.SG

They were killed by the lover. - Ērrhastera atai iniskhis

/eːˈr̥ʰːastɛra ˈataj ɪnɪsˈxɪs /

ino-iskha-∅-is atai ērrho-aster-a

to_love-AG-AGT.SG they.3.PAT.PL to_be.ACT-IND.PRFV-1.AGT.SG

The lover killed them.

Locative

Locative proper

- See also: Ris possession

The locative case (loc) vaguely corresponds to the English spatial prepositions of "by", "at", "in", and "on". However, the Ris locative also bears a temporal usage, similarly to English "in an hour", "today", "after three o'clock".

The Ris language does have adpositions in the traditional sense, to control the exact location of the locative.

| Amnayya azimat? | ʔineyna enazamut. | amagyat | |||||||||||

| /aˈŋ͡majːa azˈiŋ͡mat/ | /ˈʔinɛjna ɛnˈazaŋut/ | /aŋaɡˈjat/ | |||||||||||

| amna | -yya | azima | -t | ʔiney | -na | en- | azama | -ut | am- | agy | -at | ||

| you/2.sg.c.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | home/sg.n | -n.loc | lie/act.ind.stat.n.sg | -it/n.pat.3.sg | below.locp- | house/2.sg.c | -n.loc | after/behind.locp- | hour/f.sg | -f.loc | ||

| Are you at home? | It lies below the house. | In an hour | |||||||||||

Lative locative

Related to location is movement, and the locative can through a construction with the lative particle ‹a› /a/, transform the locative meaning to a lative or translative one. Before a null-onset, it is pronounced /aɦ/.

The particle and the proclitic adpositions will be marked green.

| Gam a azimat! | ʔinena a enazamut. | Ann erʔit. | |||||||||||||

| /ɡøŋ aɦazˈiŋat/ | /ˈʔinɛna aɦ ɛnˈazaŋut/ | /anː erˈʔit/ | |||||||||||||

| gam | a | azima | -t | ʔine | -na | a | en- | azama | -ut | a- | -nn | erʔi | -t | ||

| come/act.dir.pos.m | latp | home/sg.f | -f.loc | lay/act.ind.dyn.n.sg | -it/n.pat.3.sg | latp | below.locp- | house/n.sg | -n.loc | latp | -m.pat.1.sg | anger/f.sg | -f.loc | ||

| Come home! | Put it below the house. | I am getting angry. | |||||||||||||

Possessive locative

The third purpose of the locative case is that it is also the main tool to express possession, a construction very close to the Celtic and Finnish equivalents, confer:

- Minulla on talo - I have a house (literally: There is a house at me)

This is the one of the ways of expressing alienable possession in Ris, and it is as such never used for inalienable constructions.

| gat azamayya | Manim gat azamayya! | ||||||||

| /ˈɡ͡bøt aˈzaŋajːa/ | /ˈŋ͡mønin ˈɡ͡bøt aˈzaŋajːa/ | ||||||||

| g | -at | azama | -yya | emin | g | -āt | azama | -yya | |

| I/1.sg.m | -c.loc | home/sg.n.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | see/act.dir.pos.c.pl | I/1.sg.m | -c.loc | home/sg.n.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | |

| My house | Behold my house! | ||||||||

| azamayya gat ta trasino | Atnvayya gat girgemn. | ||||||||||||

| / aˈzaŋajːa ˈɡ͡bøt wa taˈtr̥asino/ | / atˈŋ͡majːa ˈɡ͡bøt ˈɡirɡemn/ | ||||||||||||

| azama | -yya | g | -at | ta | trasino | atn | -va | -yya | g | -at | girge | -mn | |

| home/sg.n.pat | -cop.act.ind.stat | I/1.sg.m | -f.loc | def art.n | green(n.sg.pat) | dog/sg.n | -agt.n.sg | -cop.act.ind.stat | I/1.sg.m | -f.loc | see/act.ind.dyn.n.sg | -you.m.pat.2.sg | |

| My green house | My dog barks at you. | ||||||||||||

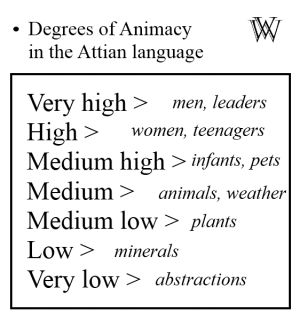

Animacy

Just as the Ris language makes a difference regarding gender, a fairly strong distinction in animacy[*] is made, mainly for semantical and grammatical reasons, since there is no morphological distinction.

The Ris rules of animacy dictates that no inanimate objects may stand in the agentative case. Inanimate nouns are perceived as incapable of actually performing deliberate actions. Inanimates that are the subjects of an action are therefore most often marked with the instrumental case. This construction forces the speaker to directly name an animate agent, use a passive construction, or to use an indefinite pronoun. Inanimate, or less animate nouns also have a lesser probability to be compatible with verbs connected with higher degrees of animacy, like the words for "to talk", "to think" and "control".

There are several different degrees of animacy, which at times also intertwine with salency. The grading goes from Very high to Very low and spans 7 degrees. The top and most animate nouns are humans, and especially men and leaders. Women normally rank as at least as animate as men, but they can in certain circumstances be degraded to indicate inferiority. The least animate substantives are minerals, abstraction and in part; plants.

Don't blame the stone

Below is an example of someone hit with stones. Here, the subject impossibly could be marked with the agentive, taking their inanimacy in regard. Instead, you may put the subject in the instrumental case, and mediopassivise the verb. Alternatively the subject is degraded to an oblique, and a new subject is introduced.

| vanev ittimann | vanun tutinn | yatva vanum titann | |||||||||||||

| /ˈwanɛw itˈtiŋanː/ | /ˈwanun ˈtutinː/ | /ˈjatwa ˈwanuŋ ˈtitanː/ | |||||||||||||

| vana | -ev | ittim | -ann | vana | -un | tuti | -nn | yat | -va | vana | -um | tita | -nn | ||

| stone/n.pl. | -n.pl.agt | hit/ind.dyn.n.pl | --m.pat.1.sg | stone/n.pl | -n.pl.ins | hit/med.dyn-stat.m.sg | --m.pat.1.sg | someone/m.sg | -m.agt | stone/n.pl | -n.pl.ins | hit/ind.dyn.m.sg | --m.pat.1.sg | ||

| *Stones hit me | I am hit with stones | Some guy hits me with stones | |||||||||||||

Both verbs and nouns have different inherent animacy. Both the type of noun and verb are thus essential to interpret whether it can be the in the agentative case. Some verbs are more inherently animate than others in the Ris language, determining whether inanimate subjects may perform them; the word "to speak", thana, is used unexclusively for humans. Less animate subjects cannot perform this verb and are therefore coupled with another, more appropriate, one. Please note that only because inanimate nouns are less likely to perform more animate actions, more animate nouns may act out inanimate verbs.

Below is table with example nouns and verbs with their respective animacy. Please note that the first two degrees most often intertwine. It is common for slightly sexistic or separatistic speakers to use work-arounds when speaking about women or children: Instead of saying that they are capable, they would say they can do (it). In other terms; stative or generic verbs describing characteristics are less likely to be used with women. They have to satisfy with the appropriate dynamic verb.

| Degrees of Animacy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very High | High | Medium high | Medium | Medium low | Low | Very low |

| man | women, children | infants, pets | animals, weather | plants | minerals | abstractions |

| to talk | to communicate | to bark, to be noisy | to be green | to be heavy | to be complicated | |

Possession

Possession is a complicated subject in Ris grammar. There are about seven different constructions to indicate ownership, depending on context. The primary parameters is the alienability of the possessed, but also the animacy of the possessor.

Predicative possession

Copula and dative

Copula and locative

Copula and instrumental

Transitive construction

Adnominal possession

Genitive construction

Locative construction

Dative construction

Samples

- thýo hā́ katḗrrazas

- tḗ rhánzatha

- gytḗra ouārathí ērikí

- inḗ gýtē mna.

- Atḗ, inḗ gytḗn ~ Atḗ, inḗ gýtē ne!