Verse:Chlouvānem Inquisition: Difference between revisions

m (→Health) |

m (→Names) |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

* ''chlouvānumi murkadhāni bhælā'' - the designation in official documents, "Land of the Chlouvānem Inquisition". | * ''chlouvānumi murkadhāni bhælā'' - the designation in official documents, "Land of the Chlouvānem Inquisition". | ||

In other Calemerian languages, there often is a distinction between the country (usually called Chlouvānem land) and the Inquisition. For example, in [[Skyrdagor]] the Chlouvānem people are called ''Snovanem'' and their country is ''Snovanemszikt'', but the Inquisition as a political body is often called ''Murkadanavi''. In [[Cerian]], Chlouvānem people are called ''Imúnigúronen'' (from the [[Iscegon]] phrase ''in mutenen ingúron'' "Eastern invaders", a term applied to many other peoples in Western history but revitalized in the Early Modern Age and applied to the Chlouvānem - the easternmost hostile people they knew about) and their country is ''Imúnigúroná'', but the Inquisition is either '' | In other Calemerian languages, there often is a distinction between the country (usually called Chlouvānem land) and the Inquisition. For example, in [[Skyrdagor]] the Chlouvānem people are called ''Snovanem'' and their country is ''Snovanemszikt'', but the Inquisition as a political body is often called ''Murkadanavi''. In [[Cerian]], Chlouvānem people are called ''Imúnigúronen'' (from the [[Iscegon]] phrase ''in mutenen ingúron'' "Eastern invaders", a term applied to many other peoples in Western history but revitalized in the Early Modern Age and applied to the Chlouvānem - the easternmost hostile people they knew about) and their country is ''Imúnigúroná'', but the Inquisition is either ''šá Murocadána'' or ''šan sévíson Imúnigúronen'' (literally Chlouvānem Church). | ||

==Chlouvānem ethnicity== | ==Chlouvānem ethnicity== | ||

Revision as of 16:29, 6 April 2017

| Native name | Chlouvānumi murkadhānāvīyi bhælā |

|---|---|

| Capital (and largest city) |

Līlasuṃghāṇa |

| Ethnic groups | Chlouvānem 96,6% Bronic 0,8% Skyrdegan 0,6% Others 2% |

| Religion | Yunyalīlti 100% |

| Nationwide official language | Chlouvānem |

| Other languages | Various local vernaculars Cerian (regional, Northwest) Auralian (regional, Northwest) |

| Demonym | Chlouvānem |

| Area | TBA — around 14,400,000 km2 (5,560,000 mi2) |

| Population | 1,469,829,096 (35.02.ᘔƐ.66012) (4E ᘔƐ (13110) census) |

| Population density | TBA — about 101/km2 (262/mi2) |

| Government | Elective theocracy |

Great Inquisitor

|

Hæliyoušāvi Dhīvajhūyai Lairė |

Baptist

|

Huliāchlærimāvi Lænkæša Martayinām |

| Currency | Inquisitorial Talān (murkadhānāvīyi talān) |

| Drives on the | left |

The Chlouvānem Inquisition (natively Murkadhānāvi; see below for other names) is a country on the planet of Calémere. With a population of 1.469 billion people[1] it is also its most populated country (counting about 17,8% of the total Calemerian population). It is a federally organized theocracy, consisting of 156 dioceses (juṃšañāñai) with a large degree of autonomy; the dioceses are mostly a contiguous territory extending throughout the whole continent of Márusúturon (Mārṣūtram in the Chlouvānem language), covering about 40% of it; some dioceses are entirely insular in the neighboring seas, though the islands of Kāyīchah are much closer to Védren, effectively making the Inquisition a transcontinental country. The Inquisition covers approximately 14.4 million square kilometers (about 8% of the land areas on Calémere), which makes it also the largest country on the planet.

Counted as separate entities are also many territories - mostly islands with military bases or scientific stations - across the planet; the most notable of those is the Lalla Kehamyuita (“High North”), jointly governed with Askand, Skyrdagor, and Brono, which is a large but almost uninhabited territory consisting of the whole part of Eastern Márusúturon north of the 68th parallel north.

Capital of the Inquisition is the holy city of the Yunyalīlta, Līlasuṃghāṇa, in the southern part of the Great Chlouvānem Plains.

While the consolidation of the Inquisition as a single state is fairly recent, the Inquisition as a body was formed in the Great Plains at the beginning of the Second Era as a churchlike body run by the Inquisitors (murkadhānai, literally “black hands”, due to many early rituals requiring the use of lunīla berries and their pitch-black unedible juice), the preachers of the Yunyalīlti religion.

Chlouvānem peoples — a métis ethnicity formed by interracial breeding of various prehistoric peoples of the Great Plain, most prominently the Ur-Chlouvānem[2], a Lahob population who had migrated from Northern Evandor across the vast steppes of Márusúturon before reaching the Plains, as well as the Ancient Kūṣṛmāthi, founders of the first urban civilization on the continent — in the next two thousand years preached their religion and expanded throughout most of the continent, assimilating local peoples but creating numerous countries that were held together by their common religion and the use of Classical Chlouvānem as a lingua franca among the other vernaculars that developed from it. The beginning of the Fourth Era was marked by the formal unification of all Chlouvānem countries into a single country, where religious and civil government coincide.

The Chlouvānem Inquisition is today the main superpower of the Eastern Bloc on Calémere, ideologically contrasted to the secular and plurireligious West (despite it being the only major theocracy and despite many prominent Eastern countries not being even Yunyalīlti) and the leading technological innovator on the planet. It is a highly developed country following a religion-driven regionally planned economy with a strong focus on environmental-friendly policies; it consistently ranks in the highest places when it comes to human development and quality of life, and has the second-lowest income inequality on the planet, after the fellow Yunyalīlti country of Brono. On the social side, though, the Inquisition implements a strict monoreligious policy, with non-Yunyalīlti people (heretics) being most often either converted or legally persecuted and killed en masse.

Despite formal peace being strived for and kept by both sides, the relations between the Inquisition and the West remain tense, particularly due to the former’s repeated calls to holy war; the last such conflict (called the East-West Global War), ninety years ago during the reign of the extremely radical Great Inquisitor Kælahīmāvi Nāʔahilūma Martayinām, ended in a white peace when the conquest-bound Chlouvānem armies were forced to retreat and leave the then-economically collapsed West due to a near-implosion of the Inquisition due to a series of revolts, particularly in the annexed territories of Brono and Greater Skyrdagor.

Names

The name of the Inquisition in Chlouvānem is Murkadhānāvi, meaning "of the Inquisitors", where "Inquisitor", murkadhāna, translates to "black hand". The Inquisitors originally were the first preachers of the Yunyalīlta after the Chlamiṣvatrā[3] Lelāgṇyāviti, and their hands were black due to the liturgical use of lunīla berries. These berries, commonly growing all throughout the wetter eastern half of the Lāmiejāya plain (as a climatic/cultural region, thus including also the Jade Coast and its basins), are not edible but have a dense pitch-black juice that was used in many shamanic rituals - often reinterpreted and passed into early Yunyalīlti ones - and also as a common black dye.

The Inquisition was founded by these preachers as a kind of guild in order to better guard and preserve liturgical texts and set up scientific orders studying the world - in fact, monasteries and temples were the centers of science for two millennia, and even today most of the largest libraries in the whole planet are those of Yunyalīlti temples. The Inquisition then gained political power and became a sovranational organization that had influence on every forming Chlouvānem realm - not unlike the Church in European history - until the beginning of the Fourth Era when all Chlouvānem nations were united under a single government - the Inquisition.

In Chlouvānem, there is thus no distinction between the Inquisition as a country and as a political organization, being both called murkadhānāvi. The country is however also often referred to as:

- murkadhāni bhælā “Land of the Inquisition”;

- chlouvānumi bhælā "Chlouvānem land";

- chlouvānumi murkadhāni bhælā - the designation in official documents, "Land of the Chlouvānem Inquisition".

In other Calemerian languages, there often is a distinction between the country (usually called Chlouvānem land) and the Inquisition. For example, in Skyrdagor the Chlouvānem people are called Snovanem and their country is Snovanemszikt, but the Inquisition as a political body is often called Murkadanavi. In Cerian, Chlouvānem people are called Imúnigúronen (from the Iscegon phrase in mutenen ingúron "Eastern invaders", a term applied to many other peoples in Western history but revitalized in the Early Modern Age and applied to the Chlouvānem - the easternmost hostile people they knew about) and their country is Imúnigúroná, but the Inquisition is either šá Murocadána or šan sévíson Imúnigúronen (literally Chlouvānem Church).

Chlouvānem ethnicity

The ethnic definition of Chlouvānem is very broad: popular usage, converted into a legal definition, defines as Chlouvānem everyone who:

- is a follower of the Yunyalīlta;

- is part of a cultural group entirely based on Yunyalīlti practices of Chlouvānem tradition, or has been considerably influenced by it (inherently linked with being Yunyalīlti believers);

- is part of a cultural group linguistically in a state of diglossia with a local, regional “word” (bhælāmaiva[4]) and Classical Chlouvānem, the latter inherently tying said cultural group to all other Yunyalīlti ones with similar characteristics.

Being a follower of the Yunyalīlta is, in most cases, enough to make the other two points true, and inside the borders of the Inquisition that’s almost always the case; in fact all Yunyalīlti who are not originary of either Brono, Fathan, Ikalurilut (countries with overwhelming Yunyalīlti religious majority), of Greater Skyrdagor (where about a quarter of the population is Yunyalīlti, up to 54% in the country of Goryan), or of a few other traditional minorities around the world (most notably Holenagic Yunyalīlti) and live in the Inquisition are Chlouvānem.

In fact, during the reign of Great Inquisitor Nāʔahilūma, no such distinction was included in censuses, as the only possible distinction to be done among humans was either Yunyalīlti or heretic.

The Chlouvānem ethnicity and culture were historically born through interbreeding of various peoples in prehistoric times, to the point that different ethnicities came to identify as one; there are various theories on why among all of those languages Chlouvānem - the last one to come there chronologically - came to be the dominant one, but most probably there was a religious background, namely that it was the first language of the Chlamiṣvatrā, and the language she spoke the most during her predication[5].

Demographics

Due to this extremely broad definition of ethnicity and due to the governmental policies extremely hostile towards non-Yunyalīlti, the Chlouvānem Inquisition is unique for its size and population as 96,6% of the population is ethnically Chlouvānem; it is to be noted, anyway, that this broad definition allows inside of it extremely large cultural variations, often also shaped by climate and environment and not just because of different cultural substrata.

That 3,4% of non-Chlouvānems is mostly due to three factors:

- Titular ethnicities of “ethnic dioceses”, a few dioceses where there often is a local indigenous pre-Chlouvānem language with legal recognition there. These titular ethnicities are rather small because, like all other Chlouvānemized peoples, they have interbred with Chlouvānems and taken cultural influences, as well as converted to the Yunyalīlta, and the “purest” form of their culture mostly survived in remote valleys or plateaus; in fact, in most ethnic dioceses the local titular ethnicity does not count for more than 10% of the population, with the majority of people having origins in both that ethnicity and in not-better-defined Chlouvānem;

- People of Western (Evandorian) origin in the Northwestern coastal dioceses, which were formerly colonies of Evandorian powers (some small lands of Auralia, Ceria, and the late Kingdom of Bankráv). Auralian, Cerian, Majo-Bankravian, and Nordulic are all minority official languages in parts of this area. Still, most of them have cut ties with their ancestral homeland and they're becoming part of mainstream Chlouvānem culture, even though with this regional influence.

- Some ethnically and linguistically Bronic or Skyrdegan peoples near the borders with Brono and Greater Skyrdagor.

Distribution

The population of the Inquisition is very unequally distributed throughout the national territory. The eastern part of the Lāmiejāya-Lāmberah plain, together with the neighboring Jade Coast and its surroundings, is the most densely populated area on the whole of Calémere, and similar densities may be found in coastal Haikamotė, Hirakaṣṭė, and Kainomatā dioceses in the East. On the other hand, there are many mostly rural areas as well as sparsely populated areas such as the taiga in the far Northeast, the Southern rainforest, and most high mountain chains; the most notable example is perhaps the arid belt of deserts and semi-deserts with little population due to a widespread lack of reliable water sources.

Many of the most important cities of the Inquisition are on or near the shores of the Flæmvasta Sea (flæmvasta ga jariā) - the huge marginal sea bordered by the Jade Coast, the eastern part of the Plain, the Near East, and parts of the Far East: among the most important ones there are Līṭhalyinām, Līlta, Talliė, Huñeibāma, Līlikanāna, and Ehalihombu from east to west, plus the capital Līlasuṃghāṇa that lies inland but in the tidal Lulūnīkam lake (lulūnīkam ga gėrisa), and Lāltaṣveya which lies on the Lāmiejāya delta.

Largest cities

| No. | City[6] | Diocese | Population12 (4E ᘔƐ) | Population10 (4E 131) | Tribunal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Līlasuṃghāṇa (*) | Nanašīrama | 9Ɛ.42.535 | 29,698,169 | Jade Coast Area |

| 2 | Ilėnimarta (*) | Kanyāvālna | 56.2Ɛ.ᘔ69 | 16,484,913 | Jade Coast Area |

| 3 | Līṭhalyinām (*) | Latayūlima | 44.ᘔ0.Ɛᘔ9 | 13,148,337 | Jade Coast Area |

| 4 | Līlta (*) | Mīḍhūpraṇa | 3Ɛ.48.691 | 11,792,845 | Jade Coast Area |

| 5 | Cami (*) | Haikamotė | 3ᘔ.03.475 | 11,452,121 | Northern Far East |

| 6 | Līlikanāna | Āturiyāmba | 31.09.215 | 9,222,641 | Southern Far East |

| 7 | Mamaikala | Sūmrakāñca | 24.08.133 | 6,981,303 | Namaikęeh / Northern Plain |

| 8 | Galiākina | Galiākñijātia | 21.ᘔᘔ.350 | 6,445,932 | Jade Coast Area |

| 9 | Līlekhaitė | Hūnakañjātia | 16.6ᘔ.501 | 4,621,393 | Near East |

| 10 | Naiṣambella (*) | Yayadalga | 16.12.310 | 4,503,612 | Southern Far East |

| 11 | Lāltaṣveya | Aṣasārjātia | 14.Ɛ5.199 | 4,218,309 | Eastern Plain |

| 12 | Yāmbirhālih | Ārvaghoṣa | 14.55.0Ɛᘔ | 4,093,774 | Jade Coast Area |

| 13 | Lūlunimarta | Ogiñjātia | 13.40.Ɛ6ᘔ | 3,817,090 | South |

| 14 | Kuma Nīmāliša | Ndejukisa | 11.ᘔ0.656 | 3,443,106 | West |

| 15 | Yotachuši | Hachitama | 10.74.425 | 3,138,653 | East |

The largest metropolitan area in the Inquisition is the one extending mainly on central-eastern Haikamotė diocese, centered on Cami, with a population of 43,357,289 (1.26.2Ɛ.03512) people according to the most accepted definition.

Population growth

Compared to other developed nations, the Inquisition also has a relatively high fertility rate, with a median of 2.2 children per woman; despite infant mortality sharply declining in the last hundred years (to the point that the Inquisition has one of the lowest rates on the planet) and better economic conditions, the fertility rate has not declined that much due to a traditional preference for large families and need for workers in the agricultural sector.

As this has been cause of growing concern in some areas, especially the already overpopulated parts of the nation where the largest cities lie, the government has introduced a program of colonization, offering economic benefits to those from the main populated areas who, once reached age of majority (end of the 16th year), settle in “development areas”, dioceses with large thinly-populated areas. The Inquisitorial fertility rate has also been a source of concern in some countries, as some politicians there have spoken of a “Chlouvānem plan” for world colonization: this is particularly prominent in Ikalurilut, as it has seen many Chlouvānem immigrants in the last three decades and now ethnic Chlouvānems have risen from 3% to 17% of its population.

Immigrants to the Inquisition mostly come from Dabuke lands in northeastern Védren and western Márusúturon (the latter areas bordering with Chlouvānemized Dabuke lands part of the Inquisition); due to the widespread instability, poverty, and often war in these areas of the world, many displaced people flee these lands and because of geographical proximity the closest “safe” areas are the Western dioceses of the Inquisition. Due to most Dabuke people being animists and to Western Chlouvānem culture being born as a hybrid between “mainstream” (or Plains) Chlouvānem and the former Eastern Dabuke cultures, they’re often easily converted and integrated into it.

Skin colour

As predictable given the métis origins of the Chlouvānem people and their cultural-based ethnicity, skin colour is fairly unimportant in Chlouvānem society, as it has (even on ID cards) much like the same value as hair or eye colour. Different skin colours are however interesting in their distribution, and often it is a sign of a certain geographical origin.

Calemerian skin colours, in Chlouvānem usage, are grouped in eight major definitions, none of them coming even close to an absolute majority (unless the flugasniė and hailaxniė groups are taken as a single one).

Small numbers in brackets after the definitions roughly indicate its range in the Von Luschan chromatic scale. Note that the chlebmæxhliniė type does not occur on Earth and is therefore not represented there.

- the naleimurkaniė group (36-34) is the darkest skin colour of all, and in the Inquisition it is typical in the Eastern Islands as well as a few areas in the West and along the southernmost coasts. About 7% of all Chlouvānem belong to this group.

- the lallamurkaniė group (33-28) is the typical black skin, and is legally the relative majority among Chlouvānem people[7], with 28% of the population. It is common all throughout the nation, but from the Plain it increases the further West one goes, up to more than 90% in some of the westernmost dioceses.

- the flugasniė group (27-23) is the one most people on Calémere frequently associate with Chlouvānem people, as it is the relative majority in nearly all of their heartlands; the mid-high skin colour in this range (24, 25, 26) is probably the most common overall there. It is legally the third-largest, with 24% of all Chlouvānem.

- the hailaxniė group (18-20) is another stereotypically Chlouvānem-only skin colour, relative majority in many areas of the Plain, in the southern rainforests, and in the East. It is legally the second-largest, with 26% of all Chlouvānem, but popular usage hardly distinguishes it from the flugasniė group.

- the chlebmæxhliniė group (off-scale, closest to 18 or 20 but much more yellowish and somewhat greenish) is the rarest of all Calemerian colours, and second rarest in the Inquisition with 2,5% of all people (it is to be noted though that Chlouvānem with this skin colour are the majority of all such Calemerian humans), mostly in the northwestern outback - though nowadays nowhere the majority.

- the niværeniė group (15-17 plus 21 and 22) is the colour of “dark-skinned whites”, not particularly common in the Inquisition as it amounts only to 4,5% of the population, mainly in the inland West and scattered among major cities in the rest of the nation.

- the julkniė group (7-9 plus 12-14, though more peachlike) is a light skin colour mostly common in the Northeast and parts of the East, as well as scattered elsewhere; it amounts to 6% of all Chlouvānem.

- the vindraniė group (11 and lower) is the colour of “whites”: despite being fairly common on Calémere it is hardly native to the lands of the Inquisition, apart from the taiga in the far Northeast and the islands off the Northeastern coast, as well as the northwestern dioceses which were formerly colonies of Western powers; being those historically sparsely populated areas, ancestral people of those areas are few and as such it is the rarest group, amounting to only 2% of all Chlouvānem.

Health

The Inquisition has the fourth-highest median life expectancy on Calémere (after Brono, Karynaktja, and Holenagika), with ~71.3 (5Ɛ.412) years for males and ~74.8 (62.ᘔ12) for females[8]; life expectancy has grown noticeably in the last century after the newest progresses in science were able to finally defeat or find easy cures to many common tropical diseases that historically plagued large parts of the territory.

The main health issue among Chlouvānem people is considered to be the suicide rate. Suicide (demikaudaranah) is the leading cause of death for people under 4012 and has grown to become a serious problem. The rate is very high due to the social pressure inherent in Chlouvānem culture, which has often led people, especially young workers and students, to be easily ashamed for even minor mistakes or failures and Chlouvānem society not being particularly tolerant of this. Due to the Yunyalīlti worldview valuing the community more than the individual, suicide has historically been considered the most honourable way to die, and part of a process of natural selection, as the dead’s place in the community will be taken by someone better suited.

These reasons have also led, especially among young people (particularly the age range from 1212 to 2212) to the popularity of "suicidal games" (demikaudarfildoe, pl. -fildenī): actual plannings of mass suicides masked as games. This has been a particularly hot topic in the news since in 4E ᘔ7 (12710) 43 young people committed suicide on the same day across the diocese of Kainomatā; while many such games have been stopped and the organizers often executed, some of them periodically pop out and it has been estimated that many hundreds of all yearly suicides of young people in that age range is due to these phenomena. Parts of the society, though, haven't condemned these games as much as the government did, with people even referring to them as a kind of "needed help" in order to find a simple and right way to do it.

Nowadays, even some of the most traditionalist people have recognized that suicides in the Inquisition are a serious problem as suicide rates, particularly among people aged 1612 to 2412, have continued to rise yearly for the last 15 years, and many failed attempts have led to people frequently becoming paralyzed or with other serious injuries and thus incapable to lead a normal life. Many suicide hotlines have been set up by local governments in order to give assistance and some dioceses have begun to provide psychological visits for free to “vulnerable subjects”, and there have been cases of employers being convicted and serving 2+6+2 months prison sentences[9] for instigation to suicide (demikaudarīlgis) - there have been however pressures towards Inquisitors in order to give harsher sentences for such crimes, including a full 7+7 sentence[10]; anti-suicide politics have also resulted in more surveillance near bridges at night and especially many lifeguards being employed all night long along beaches after many people committed suicide by drowning themselves into the sea or lakes; anyway, the results are still hard to see as, despite governmental efforts, popular opinion still sees suicide as an honorable act.

Geography

Climate

Flora and fauna

Political subdivisions

In the Inquisition there are three major levels of local administration: the diocese, the circuit, and the parish.

The highest level is the diocese (juṃšañāña), comparable to a federate state; their head is a bishop (juṃša). Many dioceses in an area with shared economical and cultural characteristics are grouped in an administrative unit called tribunal (camimaivikā), which intervenes in common regional economic planning and is as well an important statistic unit.

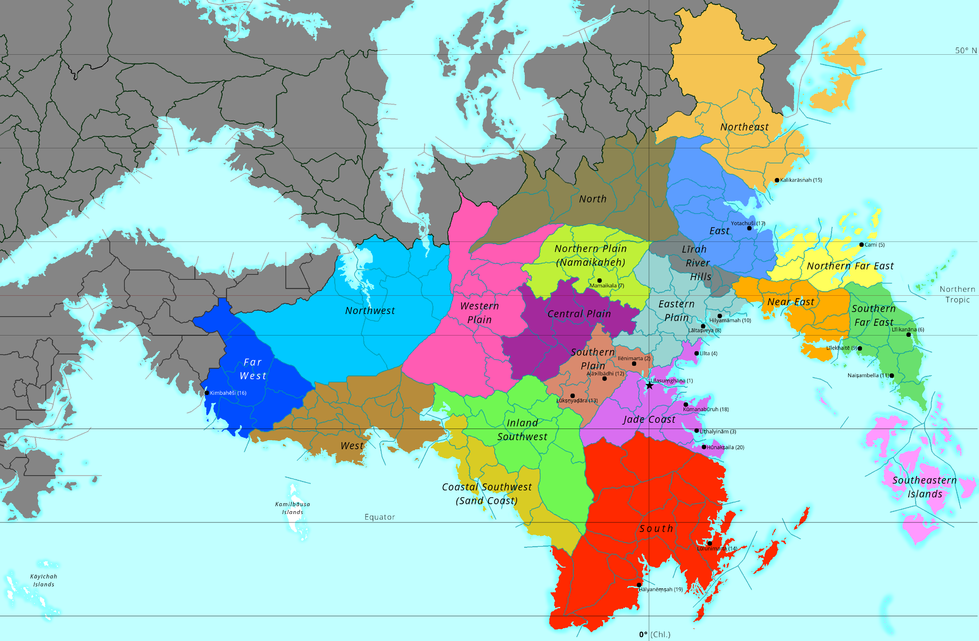

There are in total 156 dioceses in the Inquisition, divided into 18 tribunals (but two dioceses are not part of any tribunal, both insular dioceses between the rest of the Inquisition and the continent of Védren): Jade Coast Area (16, lilac in the map above), Eastern Plain (10, dark light blue), Namaikęeh - Northern Plain (7, brown), Central Plain (9, violet), Western Plain (7, golden orange), Inland Southwest (8, earth green), Coastal Southwest (6, deep green), South (14, light blue), Near East (6, pale orange), Southern Far East (7, red), Far Eastern Islands (6, grayish blue), Northern Far East (9, yellow), East (9, light green), Northeast (9, orange), North (10, dark light blue), Near West (6, purple), Northwest (7, light blue), and West (10, dark blue). Population of the dioceses ranges from 1.67.ᘔƐ.ᘔ0212 (55,717,346) (Haikamotė in the Northern Far East) to 7.21712 (12,403) (the Nukahucė islands, a remote chain of coral atolls part of the Far Eastern Islands tribunal but somewhat isolated from them). Diocese area ranges from 908,924 km2 (Kehamijāṇa, the northernmost diocese, almost entirely consisting of sparsely-populated taiga) to 208 km2 (the Nukahucė islands)[11].

Some dioceses consist of two separate administrative units with a single religious head - these are mostly newer developments, where effectively a new "state" has been created for all matters except the most strictly religious ones. Depending on the diocese, these separate units may be called provinces (ṣramāṇa) - for larger but less densely populated areas - or quaestorship (ṭūmma) - for smaller, mostly urban areas. Quaestorships are a special kind of administrative division, as they are only divided in municipalities, but they are normally counted as cities statistically - for example the capital city of the Inquisition, Līlasuṃghāṇa, is listed as the nation's largest city, with 9Ɛ,4 raicė/29.8 million inhabitants - there is however no such entity as the city of Līlasuṃghāṇa, but only its quaestorship. There are in total six quaestorships in the Inquisition: Līlasuṃghāṇa (diocese of Nanašīrama), Ilėnimarta (diocese of Kanyāvālna), Līṭhalyinām (Latayūlima), Līlta (Mīdhūpraṇa), Cami (Haikamotė), and Naiṣambella (Yayadalga); apart from the latter (counting 16,1 raicė/4.5 million people), all other ones have more than 36 raicė (~10.4 million) inhabitants and are the five largest cities of the country.

The next local level is the circuit (lalka), whose denomination changes in some dioceses — including hālgāra (district) and others — without major differences in competences (though it should be noted that competences of circuits or equivalent administrations are not centralized, but defined by the diocese or province).

The lowest level of local administration is the "municipality" one — whose names are in most dioceses either parish (mānai), city (marta), or sometimes village (poga). The distinction between them is mostly of population, with municipalities above a certain population (in many dioceses 40.00012 (82,944) people) being considered cities. The distinction between villages and parishes is more blurry and varies more between each diocese, with villages usual ly being independent municipalities whose populations are either very small in size compared to nearby ones, or located in sparsely populated areas. Clusters of nearby mid-small parishes often form an entity called inter-parish territory (maimānāyuseh ṣramāṇa), sharing between them some basic services like recycling, local transport, or fire protection.

While the lowest independent division is the parish (including cities and villages), a minor area in a parish may be recognized as a hamlet (mūrė) (note that some dioceses use the term for village (poga) instead), which for cities is usually a borough (martauseh poga, literally "urban village"). Note that cities may also have hamlets: boroughs are usually defined as such if many of them form a large contiguous urban area; smaller inhabited places in rural areas administered by a city are still hamlets.

Large uninhabited or extremely sparsely populated areas are often not assigned to any municipality, but are administered by the circuit and defined as an extra-parish territory (šrimāṇāyuseh ṣramāṇa).

History

Law and politics

The Inquisition’s political and legal systems are both based exclusively on religious law: the laws of the country are based on the interpretations given by the Inquisition to the holy books that collect the speeches the Chlamiṣvatrā gave, as well as on a few more later writings. Particularly important in the legal system are the Books of Law, which are the non-dogmatic book periodically revised to collect landmark sentences.

Charges and bodies of the Inquisition

The Great Inquisitor

The Great Inquisitor (camimurkadhāna) may be roughly described as a kind of elective absolute monarch. Her powers are both political and religious (but note that there’s no difference between them in the Chlouvānem view) and include:

- being the head of state and head of both legislative and executive power: it is the Great Inquisitor that ultimately has the final judgement on all things (with only a few small but important exceptions) that the Inquisitorial Conclave (murkadhānumi lanedāmeh, the “parliament”) and the Table of Offices (flušamaili eṇāh, the “government”) do, and she could block everything if she thinks it is necessary. In an extreme case (that, however, still happens sometimes), the Great Inquisitor could write a law and force the Inquisitorial Conclave to approve it without any edit.

- if necessary, she has the power (and obligation) to write Encyclicals (yaivjātietadhulta, pl. -dholtiė) or Thematic Letters (nañjātitadhulta); the former are meant for all Yunyalīlti dioceses on the planet; the latter only for those that are a part of the Inquisition as a country. These are documents where opinions or ethico-social themes are given, often containing indications for local governments on how to deal with them.

- she is the head of a few Offices (sg. flušamila, pl. flušameliė) with “religious” powers - that means those that affect the whole Yunyalīlti religious community and not just those in the Inquisition as a country.

- personally act as religious leader in the most important Yunyalīlti religious celebrations.

The Great Inquisitor is controlled by the Baptist (brausamailenia) as well as by the Inquisitorial Conclave, and may be forced to resign if four fifths of the Inquisitorial Conclave and the absolute majority of the Prefects (Inquisitors that lead one of the Offices) vote for it. While rare, this has happened for the last time 84 years ago with the ending of the regime of Great Inquisitor Kælahīmāvi Nāʔahilūma Martayinām after the failed conquest of the West and near-implosion of the country during the East-West War, that the Great Inquisitor herself’s policies had started.

Any Chlouvānem female starting from the age of 2212 may become Great Inquisitor; the youngest Great Inquisitor ever was younger than that as this norm didn’t exist back then (Kuliajulāvi Lañekaica, 2112 years and three months old at her election in 3E 103 (3E 14710)), but the current Great Inquisitor, Hæliyoušāvi Dhīvajhūyai Lairė, was elected four years ago (in 4E ᘔ9 / 4E 12910) at the age of 2212 years and four months, becoming the youngest Great Inquisitor since the 22-years-norm exists.

The Great Inquisitor is elected by the Conclave of Bishops (juṃšumi lanedāmeh) every 1012 years, but there’s no limit to the times a Great Inquisitor may be reëlected and she may resign whenever she wants to; often in the past Great Inquisitors remained in charge for their whole life, but today resigning is becoming increasingly common. The longest serving Great Inquisitor was Mæmihūmiāvi Kañeñuikah Læhimausa who served for 4ᘔ12 (58) years, from 4E 41 until her death 4E 8Ɛ (49-107).

The Great Inquisitor resides in the Blue Halls (kāmilai kamelьšītai) of the Inquisitorial Palace (murkadhānāvīyi amaha) in Līlasuṃghāṇa.

The Baptist

The Baptist (brausamailenia) is the second-highest charge in the Inquisition, and may be described as a kind of vice-president. The Baptist is chosen by the Great Inquisitor before her consacration, and the consacration procedures cannot begin before a Baptist is chosen.

Unlike any other Inquisitorial charge, the Baptist can be elected even among non Inquisitors, as monks and even deacons (but not other laypeople) are eligible; as for all other participants in the Conclave, 2212 is the minimum age and, since 4E 56, it is not limited to females, even though no non-cis female person has ever been Baptist. The Great Inquisitor, however, may decide do keep the previous Baptist - this happens frequently and, in fact, the current Baptist Huliāchlærimāvi Lænkæša Martayinām was chosen by the previous Great Inquisitor, Kælidañcāvi Læñchlīñchlė Mæmihūmia.

The Baptist does not have any large powers per se, but has to assist the Great Inquisitor in all of her tasks and may carry out tasks of the Great Inquisitor on her behalf when she can’t do them: by extension, it is the Baptist who acts as ad interim head of state with all of the Great Inquisitor’s powers when there’s a vacant seat. Some interpretations give the Baptist an even greater importance, especially a symbolic one, as for she’s the nearest one to the Great Inquisitor she’s the first to be able to point out abuse of power and stop blasphemous acts by the latter.

The only major limit the Baptist has is that cannot be directly elected as Great Inquisitor: she first has to refuse the charge and wait at least five years before being eligible.

The Baptist resides in the White Halls (pāṇḍai kamelьšītai) of the Inquisitorial Palace.

The Inquisitorial Conclave

The Inquisitorial Conclave (murkadhānumi lanedāmeh) is a body similar to a parliament, that has a part of the legislative power. There is a total of 612 High Inquisitors (lallamurkadhāna, pl. -dhānai), elected as follows:

- Each diocese of the Yunyalīlti world elects - usually it’s the Bishop who chooses them - two High Inquisitors;

- Every “independent” diocese - thus those that form the country of the Inquisition - elects one additional High Inquisitor;

Independent dioceses elect, in addition to the standard three, one additional High Inquisitor at 36 raicė (~10.4 million) inhabitants, plus one more every further 50 raicė (~14.9 million). Thus, the diocese of the Nukahucė islands, the least populated, with only 7.21712 (12,403) inhabitants, elects three High Inquisitors just as the diocese of Marṇadeša with 4Ɛ.28.Ɛ11 (14,737,981) inhabitants. The most populated diocese, Haikamotė, with 167 raicė (~55.7 million) inhabitants, elects seven High Inquisitors.

- The six quaestorships - Līlasuṃghāṇa, Ilėnimarta, Līlta, Līṭhalyinām, Cami, and Naiṣambella - each elect an additional High Inquisitor (aside from those already elected by the diocese: as Cami is in Haikamotė diocese, this diocese effectively elects eight High Inquisitors).

- 36 additional High Inquisitors - mostly monks - are elected by the Great Inquisitor herself. They remain in charge even if the Great Inquisitor changes, but the latter may remove them as she wishes. The Great Inquisitor who elects them may only remove them in exceptional circumstances (offences or evident indisposition or inadequacy), otherwise she may only propose their removal, which must be accepted by the majority of the Conclave.

The functions of the Inquisitorial Conclave are similar to those of a parliament. High Inquisitors are grouped based on their specializations and these groups discuss themes and write laws, which must be then approved by the whole Conclave. Themes are usually proposed by the Great Inquisitor or by the Table of Offices: High Inquisitors have the task of transform these into laws and integrate them into the Books of Law - even though the final decision is always the one of the Great Inquisitor.

Differently from a pure parliamentary system, the Inquisitorial Conclave is still inferior to the Great Inquisitor, even if it can remove her from charge with the help of the Prefects (four fifths of the Conclave and the absolute majority of the Prefects must vote for it). The Great Inquisitor can interrupt and lead the activities of High Inquisitors. The Inquisitorial Conclave meets in the Lelāh[12] Halls (lelūmi kamelьšītai) of the Inquisitorial Palace.

The Table of Offices

The Table of Offices (flušamaili eṇāh) is the closest thing in the Inquisition to a government. It is composed by a High Prefect (lallaflušamelīs) nominated by the Great Inquisitor and a variable number of Prefects (flušamelīs, pl. flušamelīye) - some chosen by the Great Inquisitor and some by the High Prefect - who lead the various Offices (flušamila, pl. flušameliė), bodies acting like ministries.

The Offices administer every branch of the Inquisition, thus including both the public administration of the Chlouvānem Inquisition and the Yunyalīlti clergy in the whole of Calémere. Generally, the Offices with a more religious and international theme, as the Office of Liturgy (brauslaijyī flušamila - which administers the Inquisitorial Tribunals (judicial organs), by collecting and publishing the most important and canonical interpretations of the Sacred Books), or the Office of Clergy (līltanorīnumi flušamila - which trains and offers sustainment to non-monastic clergy members), all have Prefects chosen by the Great Inquisitor, while those that only impact the Inquisition as a country, as the Office of Agriculture (chlæcāmiti flušamila), have Prefects chosen by the High Prefect.

Every Prefect has the right to prepare proposals for laws on a theme administered by the Office she or he runs; these proposals are then often discussed together with the rest of the Table and then presented to the Great Inquisitor and the Inquisitorial Conclave.

The Table of Offices is the assembly of the High Prefect and all of the Prefects, with often the Great Inquisitor herself present; it meets in the Dragon Hall (kaṃšāvi kamelьšītah) of the Inquisitorial Palace. All members still gathers around a table, though today it’s actually many single tables around a room. The original table around which the first meeting was held, around the mid Second Era, is kept in the Museum of Chlouvānem History in the same ward.

The Offices are all separate buildings located in various parts of the city of Līlasuṃghāṇa; most of them are in the central ward, Kahėrimaila, but a few of them are located in other wards (like Haifuriāmāh, Kālīleyālka, and the Kvælskiñšvålten).

Economy

Science, technology, infrastructure

Transport

The three main means of transport throughout the Inquisition are train, plane, and ships; cars, boats, and especially bicycles are however common local means of transport.

Road

Uniquely for such a large and high-income country, car ownership rates throughout the Inquisition are relatively low, with ~129 four-wheeled road motor vehicles every 1000 people[13]. This low rate - the lowest among developed countries on Calémere - is explained by several factors:

- Most major cities have extremely thorough and developed mass transit systems, and city growth has meant that parking spaces are few and rarer. Most dioceses with major metropolitan areas have thus introduced laws requiring people to prove they have off-street parking for any car being bought;

- Many areas in the Inquisition - including fairly large metropolitan areas like Lūlunimarta or Tariatindė - do not have roads linking them to the rest of the nation;

- As a measure to fight pollution, ownership taxes are very high, particularly in the most urbanized dioceses. Fuel - while mostly being ethanol as a byproduct of sugarcane lavoration - is also more expensive than in most other countries; it should be noted, however, that about 45% of all private vehicles are electric-powered.

Road vehicles are thus mostly trams, buses (and especially electric trolleybuses inside cities) and taxis for local transport; in most cities, bicycles, rickshaws, and cycle-rickshaws are the most common means of private transports - according to a 4E ᘔ9 (129) survey, there are four times as many bicycles than cars in the quaestorship of Līlasuṃghāṇa.

Trams are a common sight in most medium- and large-sized cities, where they often act as the most local form of transport in a network with subways and suburban railways. Many medium-sized cities also have hybrid tram/subway systems, with more central areas having a subway-like service with concurrent lines, while in the suburbs it becomes a large capacity tram service, fed by bus lines or, increasingly often in newer-built areas, cycling paths.

Rail

The train network is however the backbone of people- and freight transport in the Inquisition. Major cities all have suburban railways and, often, large subway networks, that efficiently cover large areas of territory and form the main links among communities in that area; the area of Līlasuṃghāṇa, capital of the Inquisition, has the largest subway system on Calémere, with 1,778 km of lines in operation, operating inside a large suburban railway network that extends on four different dioceses (Nanašīrama, Kāṃradeša, Lgraṃñælihaikā, and Talæñoya).

Most subway systems have at least one or more heavy rail lines - Līlasuṃghāṇa and Cami both have eight - and many other light metro lines; in a few cases there are monorail lines (with a particularly famous one being the 12 km long Waterfront Line in Lūlunimarta) and rack railways (like the Jungle Hills Line in the Līlasuṃghāṇa subway network).

People movers are also common, especially in large cities as a minor link between subway lines — a few early ones were extremely light metro lines; newer ones are rubber-tired AGTs but are still popularly treated as parts of the railway network.

The Inquisition has a railway length of about 450,000 km, linking all mainland dioceses, including steppes and rainforests; many island dioceses also have local railway systems. About 95% of the network uses the standard Chlouvānem gauge (2.2 pā, ~1,488 mm — usually called danidani ga khlatimas “two-two gauge”), but narrower gauges are used for local mountainous lines and, in some cities, for light metro lines, especially in some networks which have very narrow turns (as in the Pamahīnėna Subway). Some local lines in the North still use the Skyrdagor gauge of 1.31.3 pā (1.37.310). (~1,380 mm), even though adaptation to the Chlouvānem gauge has often been proposed - also because many countries in Greater Skyrdagor are changing their lines to Chlouvānem gauge too. Fixed block signalling is used in most of the network, but a few suburban lines near Līlasuṃghāṇa and the Cami Coastal Loop use moving block signalling, as do also many subway lines in Līlasuṃghāṇa, Ilėnimarta, Galiākina, Cami, Lūlunimarta, Huñeibāma, and Līlekhaitė.

Most of the network is nationalized, managed by local branches of the Mutada (murkadhānāvīyi tammilīltumi darañcamūh, "Inquisitorial Railway Group", also called mutacamūh), but there are some local lines, especially when part of subway networks, which are privately managed.

Train services range from those of suburban importance to high-speed, often overnight, links between cities; a few major cities are linked by high-speed maglev lines that in a few cases may operate at speeds up to 680 km/h. Railway lines are common even in rural areas, with in fact most settlements being located near railways, and rail lines being the most common means of passenger transport overall. Railway stations are also major meeting points in cities and towns, usually lying in a major square; in small towns they’re often surrounded by the main services like bars, post offices, banks, and a few shops; the most important stations in large cities are true shopping malls or even multifunctional buildings with offices and hotels.

Freight transport is also dominated by railways, giving rise to large freight depots even inside cities, even though they have often been closed, converted to public parks, and rebuilt outside the city as city growth circled them (this has happened most notably in Līlasuṃghāṇa, Ilėnimarta, and Līlikanāna, but not for example in Līlta which still has a mid-sized freight depot close to the city center).

Air and Water

Air transport is often limited to large distances, but many small towns in the rainforest, on islands, or in other sparsely populated areas often have their own airfields, with regular flights to bigger macroregional centers. Seaplane airports are particularly common in the rainforest and by islands, with some major cities having a seaplane airport usually for regional flights and a major (inter-)national airport.

Ships are a major freight transport method and also very frequently used for passenger traffic where there’s the opportunity to drastically cut travel distance - one of the main passenger ship routes being for example Taitepamba-Līlikanāna on the opposite shores of the Flæmvasta Sea. Ships are also obviously the main means of transport in insular areas.

Boats are very commonly used on rivers and are - together with railways, where present - the main method of transport in the southern rainforest and in the far northern taiga. Inside metropolitan areas with many waterways or on lakes - like Yāmbirhālih, Pamahīnėna, and to a lesser extent also Līlasuṃghāṇa - there often are boat lines connecting various settlements.

Culture

Notes

- ^ Throughout this article, quantities will be specified primarily in the decimal system, despite Chlouvānem using a duodecimal one; dates will be the main exception, first marked in duodecimal system as native Chlouvānem people do - for example, the current year is 4E Ɛ1 (4E 133). Census figures will also be provided in tables as duodecimal numbers. Unmarked numbers are base 10, unless they are expressed using Calemerian measurement units; base 12 numerals have commas and full stops reversed compared to English usage.

- ^ Usually just referred to as Chlouvānem in any other case where there's no distinction to be made; called (o)dældādumbhīñe "(proto-)language-bearers" in Chlouvānem historical anthropology.

- ^ Often translated as "Great Prophet" or "Great Master"; literally "Golden Master".

- ^ Broad legal term that encompasses all regional languages in the Inquisition, whether daughter languages of Chlouvānem or not.

- ^ It is however widely thought that the Chlamiṣvatrā spoke a Chlouvānem dialect that was not the one of the majority of people and that came to be Classical Chlouvānem, on the basis of some religious terminology like most notably lillamurḍhyā, which would have been lilāmmūrḍhiyā (morphemically lil-ān-mūg-ḍhiyā) in the "standard" dialect.

- ^ An asterisk after the city name denotes it is a quaestorship (ṭūmma).

- ^ In popular usage, the two following groups - flugasniė and hailaxniė - are considered a single one and therefore that one is considered majoritary.

- ^ Calemerian humans live on average less years than humans of Earth, note though than one Calemerian year lasts about 609,6 days on Earth.

- ^ A mild sentence in Inquisition justice, consisting of two months of forced work, six months of prison detention (including socially helpful jobs), and two months of house arrest.

- ^ Seven months of forced work plus seven months of prison detention. Note that 14 months is the length of the Calemerian year.

- ^ Land area only.

- ^ The lelāh is a sacred flower in Yunyalīlti symbology.

- ^ The sample size used was larger, and the original data is expressed as 16812 four-wheeled road motor vehicles every 100012 people (literally 224 every 1,728 people). For comparison, in 2014 there were 797 motor vehicles every 1000 people in the U.S.