Chlouvānem: Difference between revisions

| Line 760: | Line 760: | ||

The same strategy is used for attributes — ''kamilire fluta'' "blue bag" or "bag that is blue", including participial-like structures such as the following ones: | The same strategy is used for attributes — ''kamilire fluta'' "blue bag" or "bag that is blue", including participial-like structures such as the following ones: | ||

: ''lilei '''priemęlia''' fluta'' - the bag which has been given back by the person | : ''lilei '''priemęlia''' fluta'' - the bag which has been given back by the person (literally: "by the person it has been given back, the bag") | ||

: ''flutu '''pritēmęlia''' lila'' - the person who has given back the bag | : ''flutu '''pritēmęlia''' lila'' - the person who has given back the bag | ||

: ''flutu dhurvāneiti '''prikevemęlia''' lila'' - the person for whose benefit the bag has been given back to the police | : ''flutu dhurvāneiti '''prikevemęlia''' lila'' - the person for whose benefit the bag has been given back to the police | ||

Revision as of 11:18, 2 March 2018

| Chlouvānem | |

|---|---|

| chlǣvānumi dældā | |

| Pronunciation | [[Help:IPA|c͡ɕʰɴ̆ɛːˈʋaːnumʲi dɛɴ̆ˈdaː]] |

| Created by | Lili21 |

| Date | Dec 2016 |

| Setting | Calémere |

| Ethnicity | Chlouvānem |

| Native speakers | 1,450,000,000 (3874 (642410)) |

Lahob

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | lands of the Inquisition, Brono, Fathan, Qualdomailor, Gorjan (regional) |

| Regulated by | Inquisitorial Office of the Language (dældi flušamila) |

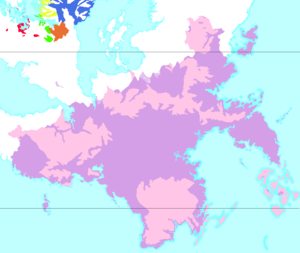

Chlouvānem, natively chlǣvānumi dældā ("language of the Chlouvānem people"), is the most spoken language on the planet of Calémere (Chl.: Liloejāṃrya). It is the official language of the Inquisition (murkadhāna) and its country, the Chlouvānem lands (chlǣvānumi babhrām[1]), the main lingua franca across vast areas of Márusúturon - most importantly Brono, Fathan, Qualdomailor, and all other countries of the former Kaiṣamā, and, due to cultural exchanges and influences in the last seven hundred years, also a well known language in Greater Skyrdagor.

It is the Yunyalīlti religion's liturgical language.

The language currently known as Chlouvānem was first attested about 2400 years ago in documents from the Lällshag civilization, as the language of a Lahob-speaking people that settled in the southern part of the Lāmiejāya-Lāmberah plain, particularly near Lūlunīkam Lake. Around year 4000 of the Chlouvānem calendar (itself an adaptation of the Lällshag one), the Chlamiṣvatrā, the great Prophet of the Yunyalīlta, lived and taught her doctrine in the Chlouvānem language, paving the way for it to gain the role of most important language and lingua franca in the at the time massively linguistically fragmented lower Plain. While the Chlamiṣvatrā's language is what we now call "Archaic Chlouvānem" (chlǣvānumi sārvire dældā), most of the Yunyalīlti doctrine as we now know it is in the later stage of Classical Chlouvānem (chlǣvānumi lallapårṣire dældā), a koiné developed in the mid-5th millennium. Since then, for nearly two millennia, this classical language has been kept alive as the lingua franca in the Yunyalīlti world, resulting in the state of diglossia that persists today.

Despite the fact that local vernaculars in most of the Inquisition are in fact daughter languages of Chlouvānem or creoles based on it, the chlǣvānumi dældā is a fully living language as every Chlouvānem person is bilingual in it and in the local vernacular; in the last half century there have been instances where the classical language itself has been replacing some vernaculars due to internal migrations, both forced and voluntary ones. About 1,4 billion people on the planet define themselves as native Chlouvānem speakers, more than for any other Calémerian language.

Chlouvānem (not counting separately its own daughter languages) is by far the most spoken of the Lahob languages (more than 99.98% of Lahob speakers), and the only one of the family to have been written before the contemporary era. It is, however, the geographical outlier of the family, due to the almost 10,000 km long migration of the Ur-Chlouvānem from the Proto-Lahob homeland at the northern tip of Evandor. Chlouvānem, due to its ancientness, still retains much of the complex morphology of Proto-Lahob, but its vocabulary has been vastly changed by language contact, especially after the Chlouvānem settled in the Plain, where they effectively became a métis ethnicity by intermixing with neighboring peoples. Still, it is possible to find lots of cognates between it and its distant relatives, even with the same meanings, like the words for "lake" (gērisa, cf. Łaȟoḇszer hetłi, < PLB *gegriso) or "worm" (tūlum, exactly the same as PLB *tūlum, cf. Łaȟ. and Łokow toł) - or even how one of the Tundra Pwaɬasd-speaking tribes is known as gěɬowupěn, which has exactly the same origin (and meaning - "golden clan") as the word chlǣvānem.

→ See Chlouvānem lexicon for a list of common words.

External History

Chlouvānem is what I - lilie21 - consider my main conlang, as it is the spiritual descendant of all conlangs I've created focussing the most on. Actually my earliest conlangs were not really conlangs, just some strange-sounding, often natlang-mimicking relexes of Italian; it was only when I was 17 that I found myself randomly reading about Ancient Greek online and that ignited in me the flame of love for linguistics - after a few months, I discovered conlanging sites and started making conlangs that were actually something more worthy of the name of "conlang", i.e. made starting from even the slightest hint of linguistic knowledge, and therefore not a relex (by the way, the first conlang I did this way was Valdimelic, which is in some way echoed in Qualdomelic).

With time, the spiritual ancestors of Chlouvānem eventually became more and more fixed at least on certain, basic characteristics (e.g. the use of Austronesian alignment, or some 90% of the phonemic inventory), but I was refining those languages more and more every version.

Chlouvānem itself is the ninth radically restructured version of Laceyiam; I started creating it in late November 2016 as I found some parts of my conworld which were too unrealistic to work - and as such by changing the whole conworld I had to change the language. I took that opportunity to change some things in the grammar that, while I liked them and they worked well, I wanted to do in some different way — mainly this arises from my love of more complex inflection patterns. As such, compared to Laceyiam, Chlouvānem has much more influences from Sanskrit and Lithuanian (which always were, together with Persian, my main influences anyway); other natlangs that influenced me a lot are Russian, Adyghe, Latvian, Old Norse (and to a lesser extent also Danish and Icelandic), Old Church Slavonic, Proto-Indo-European, (Biblical) Hebrew, Latin, and Japanese, while its actual in-world use is inspired by Arabic. Still it is an a priori language and, despite having much in common with all of these (particularly with the IE ones), is also strikingly different (the Austronesian morphosyntactic alignment, morphological expression of evidentiality and more broadly the particular emphasis on moods probably being the most noticeable things... oh, and the duodecimal number system, obviously). Moreover, I tried to create a language divergent from general Western European IE languages while keeping many - not so apparent - similarities, and, most importantly, I always tried not to just copy features from natlangs, but adapt them in some way, so that the influence is crystal clear but the actual feature works in a somewhat different way. I don't know if I've always succeeded in doing this, but at least this was - and still is - one of my main guidelines.

The morphology of Chlouvānem is very different from Laceyiam, though many words are still the same (like smrāṇa (spring), junai (foot), jāyim (girl), saṃhāram (boy)). The name of the people in the language itself used to have -ou- too, but then I changed historical phonology just enough that it caused that to become -ǣ-. Still I kept -ou- in the English name as I had used it too much and for too long in order to change it so easily.

Chlouvānem is mainly thought for my conworld, but more than any other conlang of mine it is quite on the border between an art- and a heartlang.

Variants

Chlouvānem as spoken today is the standardized version of the literary language of the mid-5th millennium Lāmiejāya plain, the one in which most sacred texts of the Yunyalīlta are written. Since then, the language has been kept alive for more than 1500 years and counting in a diglossic state with many descendant and creole languages developing in the areas that gradually came under Chlouvānem control, and Classical Chlouvānem is in fact a major defining factor of Chlouvānem ethnicity, enabling the existence of a single cultural area spread across half a continent despite the individual areas each having their own vernaculars.

Pronunciations

It’s not easy to define “dialects” for Chlouvānem, due to this history: all true dialects of Chlouvānem eventually developed into distinct vernaculars, and today’s regional variations are as such defined as “pronunciations” of Chlouvānem, in some cases moderately divergent from the standard one. Chlouvānem sources refer to them as babhrāyāṃsai “land-sounds”, but they do not only vary in pronunciation. Each major geographic area of the Inquisition has its own pronunciation; present-day standard Chlouvānem is based on the pronunciation in the city of Līlasuṃghāṇa around year 6350, but the local pronunciation has somewhat diverged, so that the city where the traditional pronunciation is closest to the standard is Galiākina, some 300 km further west. Local pronunciations are typically divided in six major groups by geographic areas:

- Jade Coast, Rainforest, and Eastern Plain (lūṇḍhyalēnei nanayi no naleidhoyi no), including pronunciations of the eastern part of the Lāmiejāya plain, the Jade Coast, and its interior (the main Chlouvānem heartlands and the northern parts of the rainforest). Standard Chlouvānem is one of these.

- Western Plain and Sand Coast (samvāldhoyi chleblēnei no), including the whole western part of the Lāmiejāya plain and the Sand Coast in the central-western Inquisition.

- Far Eastern (lallanaleiyutei), including the Far Eastern part of the Inquisition (both mainland and insular); the dioceses of the so-called Near East are frequently considered a transitional zone between this and the Eastern Plain pronunciation group.

- Eastern (naleiyutei), in the Chlouvānem East (the former Toyubeshi area).

- Northeastern (kehamnaleiyutei), in the Northeast of the Inquisition; note that the most remote areas (the far northern taiga and the insular part), due to continuous and relatively recent immigration, have a pronunciation still closer to Standard Chlouvānem.

- Western (samvālyutei), in the Western dioceses and in the coasts of the desert. As these were formerly Dabuke areas, they use distinctly more Dabuke terms than all other speakers.

Areas that do not fit in any of these groupings are often recent colonizations (or “Chlouvānemizations”), like e.g. the northern coast on the Skyrdegan Inner Sea, that do not have a truly distinct pronunciation, being a mix of speakers from different areas and tending to be very close to Standard Chlouvānem.

Vernaculars

Local vernaculars of the Inquisition (babhrāmaivai, sg. babhrāmaiva, literally “land word(s)”) are, linguistically, the daughter languages of Classical Chlouvānem. They are the result of normal language evolution with, in most areas, enormous influences by substrata.

Actually, only a bit more than half of the Inquisition has a vernacular that is a true daughter language - most areas conquered in the last 600 years, thus since the late 6th millennium, speak a creole language, where lexicon is almost completely Chlouvānem but grammar still shows huge semplifications and analytic constructions and some traits odd for Chlouvānem and those languages that developed in the heartlands. Most of the Eastern languages, however, are thought to have origined as creoles.

The main division for local vernaculars - or Chlouvānem languages - is the one in groups, as few of them are standardized and large areas are dialect continua where it is extremely difficult to determine which dialects belong to a particular language and which ones do not. Furthermore, most people speak of their vernacular as “the word of [village name]”, and always refer to them as local variants of the same Chlouvānem language, without major distinctions from the national language which is always Classical Chlouvānem[2]. Individual “languages” are thus simply defined starting from the diocese they’re spoken in, so for example the Nanašīrami language includes all dialects spoken in the diocese of Nanašīrama, despite those spoken in the eastern parts of the diocese being closer to those spoken in Takaiyanta than to the Nanašīrami dialect of Līlasuṃghāṇa - which has, however, lots of common points with the Lanamilūki Valley dialects of Talæñoya to the south.

Note that the word maiva, in Chlouvānem, only identifies a language spoken in a certain area which is typically considered to belong to a wider language community, independent of its origin. It does not have any pejorative meaning, unlike examples like e.g. lingua vs. dialetto in Italian.

The main divisions are:

- Eastern Plain/Jade Coast (naleidhoyi lūṇḍhyalēnei no maivai) — spoken in most of the Lāmiejāya Plain, in the Jade Coast and its interior, and the northern part of the southern rainforest;

- Western Plain (samvāldhoyi maivai) — spoken in the westermost parts of the Lāmiejāya Plain;

- Jungle Language (nanaimaiva) — spoken throughout the southern rainforest, as well as most of Vāstarilēnia diocese;

- Northern Plain (kehaṃdhoyi maivai) — spoken in the northern part of the Lāmiejāya Plain (the upper basin of the Lāmberah river);

- Near Eastern (mūtiānaleiyutei maivai) — spoken in the Near East, or the parts of the Central East west of the Kārmādhona mountains;

- Far Eastern (lallanaleiyutei maivai) — spoken in the Far East (east of the Kārmādhona mountains) and in the eastern islands;

- Kaṃsatsāni (kaṃsatsāni maivai) — spoken in the historic region of Kaṃsatsāna (the Eastern Tribunal);

- Sand Coast (chleblēnei maivai) — spoken on the Sand Coast (west of the Lāmiejāya plain), from Yūgarthāma and Nanyådajātia to the northernmost part of Vāstarilēnia to the south.

The other languages were all born as creoles:

- Hæligreiši-Mbusakitvi (hæligreiši-mbusakitvi maivai) — taking their name from the two extremes, Hæligreišijātia in the east (on the eastern coast of the Bay of Salt) and Mbusakitva diocese in the west. They share many traits with the Western creoles further west, but unlike them, which were Chlouvānem-Dabuke creoles, the Hæligreiši-Mbusakitvi arose from contact between Chlouvānem and speakers of Raina languages (ultimately related to Dabuke ones) that had colonized those coasts from Védren before them.

- Northeastern (kehamnaleyutei maivai) — various creoles spoken in the Northeast (north of the Padeikoli Gulf), excluding Kēhamijāṇa and Hokujaši and Aratāram islands, as well as the Hålvaren Plateau;

- Hålvareni (hålvareni maivai) — various creoles spoken in the dioceses of the Hålvaren Plateau (Mārmalūdven, Kayūkānaki, Doyukitama, and Teliegāša);

- Western (samvālyutei maivai) — creoles spoken in the West (dioceses of Ndejukisa, Makhadarīṣa, Majeatumba, Katumbunda, and Mbekalunda), with extensive Dabuke influence;

- Eirappåcīyi (eirappåcīyi maiva) — creole spoken in the diocese of Eirappåcīh, a series of high-altitude plateaus nestled between the mountains in the northwestern Inquisition (part of it is geographically the uppermost part of the Lāmiejāya valley). The diocese's name comes from Qualdomelic ejrăc pọțir "Crown of Snow", and in the area there are a few other Western Samaidulic languages, albeit spoken by only a few thousands of people;

- Kāyīchi (kāyīchi maiva) — creole spoken in the insular diocese of Kāyīchah, off the coasts of Védren. It is the least Chlouvānemized creole, as it has substantial influences both from indigenous Vedrenic languages and Cerian, due to the history of these islands, settled in part by Chlouvānem people (by the then-independent Lūlunimarti Republic) and in part by Cerians with Vedrenic slaves, and long fought between the two countries due to their strategic importance.

Many other areas, most notably the former Skyrdegan and Bronic lands (dioceses of Hivamfaida and Maichlahåryan), the far Northeast (the Hokujaši and Aratāram islands and Kēhamijāṇa), and the Northwest do not have a local vernacular, due to Chlouvānem presence there being recent (especially for Hivamfaida and Maichlahåryan) and those areas being either previously almost uninhabited (the far Northeast and the Northwestern deserts) or with lots of different ethnicities (the coastal Northwest). The main vernaculars that are actually languages that do not have Chlouvānem origin (and are commonly referred to as dældā instead of maiva) are:

- Basaumi (Bazá), the most spoken, in the ethnic diocese of Tūnambasā, the westernmost on the mainland, where it is the native language of 78% of all inhabitants. Also the official language in the neighboring country of Ênêk-Bazá;

- Hūnakañumi (Huwən-aganь-sisaat), in the mountainous areas of Hūnakañjātia ethnic diocese in the Near East (note that most of the diocese, including the city of Līlekhaitē, 10th largest in the Inquisition, mostly speaks the local Near Eastern language, derived from Chlouvānem)

- Tumidumi (sokaw y ee-tumið), in the ethnic diocese of Tumidajātia in the Near East - mostly spoken in the hills and mountains;

- Kotayumi (kotaii šɔt), in a few mountain villages in Kotaijātia ethnic diocese, Southern Far East;

- Tendukumi (tənduk sisod) in Tendukijātia ethnic diocese, Southern Far East — by percentage of people in its native area, it is the third most spoken (after Bazá and Tapirumi), being the native language of 29% of people there, though it is the least populated diocese in that area;

- Niyobumi (niyyube sesath) in the mountains and hills of the ethnic diocese of Niyobajātia, Southern Far East.

- Tanomali (nzɛk pɔb) on Tanomaliē island, the southernmost of the Eastern Islands;

- Nalakhojumi (üj nolomħoj) in the western half of the ethnic diocese of Nalakhoñjātia, Eastern tribunal. Notably, the main urban area, the city of Lānita, is almost entirely Chlouvānem-speaking;

- Halyaniumi (üš hælyaney) in most of the ethnic diocese of Halyanijātia, Northern tribunal. Note that the southermost part of this diocese has never been Halyaniumi-speaking;

- Koudavumi (kowdao hüüj) in the ethnic diocese of Koudavīma, Northern tribunal;

- Cathinumi (čathinowtawkow) in the ethnic diocese of Seikamvēyeh, Northern tribunal - also the official language in the bordering country of Nēčathiwēyē as well as in Čiwēynac;

- Daheliumi (dæhæng pop) in the ethnic diocese of Dahelijātia, Northern tribunal, mostly in rural villages. It is only the third most spoken language in the diocese, after Chlouvānem and Skyrdagor;

- Kūliamumi (kūlyam ɣozár) in the ethnic diocese of Kūliambārih, Near West;

- Tapirumi (tafhirengguk) in the northern part of the diocese of Tapirjātia, Northwest. It is especially common in the northern part, in and around the city of Imēla and by the Maëbian border (note that Tapirumi and the Maëb language are mutually intelligible), but almost nonexistant in the southern part, including the capital, Tohailena;

It should be noted, however, that all of these languages except for Tanomali are spoken in ethnic dioceses and are in official use there, with a number of L2 speakers far greater than natives due to diocese-wide teaching of them during most school years in all but a few schools.

Note that this list does not include more limited minority languages, such as the use of Evandorian languages in Northwestern dioceses, like Cerian in Ārūpalkvabī, Nordulaki in Yultijātia and Auralian in Tapirjātia - all of them mostly used by urban older speakers only. There are also completely foreign languages spoken by immigrants; studies show that Hālʾọgbi, a Spimbrionic language from the continent of Ogúviutón, has nearly a million speakers (L1 or other L2 Ogúviutónians) in the Inquisition.

Historical dialects

Phonology - Yāṃstarlā

Chlouvānem is phonologically very conservative from Proto-Lahob as it has not had a lot of changes - however, those few it had have had the effect of strongly raising the total number of phonemes, developing a few distinctions that, while not rare themselves, are rarely found all together in the same language. For example, the combination of the distinction between /Cʲ/ and /Cj/ and between /CV CʱV CV̤ CʱV̤/ means that the following sequences are all potentially contrastive: /da dʱa da̤ dʱa̤ dʲa dʲʱa dʲa̤ dʲʱa̤ dja dʱja dja̤ dʱja̤/.

Consonants - Hīmbeyāṃsai

Chlouvānem has a large consonant inventory, with 47 different consonants, divided into seven categories: labials, dentals, palatalized dentals, retroflexes, palatals, velars, and laryngeals. The Chlouvānem term for "consonant" is hīmbeyāṃsa, a compound of hīmba (colour) and yāṃsa (sound). The following table organizes consonants by their behaviour - thus, for example, the treatment of the phonetic affricates /c͡ɕ(ʰ) ɟ͡ʑ(ʱ)/ as stops.

| → PoA ↓ Manner |

Labials hærṣoke |

Dentals aṣṭrūke |

Retroflexes āḍhyāsūke |

Palatals dehāṃlūdvyūke |

Velars bhyodilūdvyūke |

Laryngeals diṇḍhūke | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain pūdre |

Palatalized1, 2 pindehāṃlūdvyūke | |||||||

| Nasals3 | m m mь mʲ |

n n4 | nь nʲ | ṇ ɳ | ñ ɲ | l [ŋ~ɴ]5 | ṃ ɴ6 | |

| Stops | Unvoiced | p p ph pʰ |

t t̪ th t̪ʰ |

tь tʲ thь tʲʰ |

ṭ ʈ ṭh ʈʰ |

c c͡ɕ ch c͡ɕʰ |

k k~q kh kʰ~qʰ |

ɂ ʔ |

| Voiced | b b bh bʱ |

d d̪ dh d̪ʱ |

dь dʲ dhь dʲʱ |

ḍ ɖ ḍh ɖʱ |

j ɟ͡ʑ jh ɟ͡ʑʱ |

g ɡ~ɢ gh ɡʱ~ɢʱ |

||

| Fricatives | f f~ɸ7 | s s | sь sʲ | ṣ ʂ | š ɕ | h ɦ8 | ||

| Approximants | v ʋ9 | y j | r ʀ10 rь ʀʲ l ɴ̆ lь ɴ̆ʲ | |||||

Table notes:

- The orthographic palatalization marker is transliterated as i before vowels and ь before consonants or at the end of a word.

- All consonants which have a non-palatalized/palatalized phonemic pair are always palatalized before /i iː i̤/, thus the contrast is neutralized there.

- All nasals except /ɴ/ may be said to be a single phoneme /N/ when preceding another consonant (except /j/), as they assimilate to the following consonant's PoA.

- Realized as [ŋ] word-finally after high monophthongs (/i iː i̤ u uː ṳ/) and as vowel nasalization after the others, including diphthongs.

- The realization of the sequences orthographically marked as lk lkh lg lgh varies regionally and, therefore, the l-phoneme can in these contexts be realized as either [ŋ] or [ɴ]. In most local Chlouvānem pronunciations, these sequences are [ŋk(ʰ) ŋɡ(ʱ)] but, in areas including notably Līlasuṃghāṇa, most of the southern Jade Coast, and the South, they are [ɴq(ʰ) ɴɢ(ʱ)].

- /ɴ/ contrasts with other nasals only before non-labial voiced stops, where it is realized as nasalization of the preceding vowel.

- Both allophones are found, in free variation in some pronunciations (e.g. Ilēnimarta, Galiākina, Western Plain), as conditional allophones in others (e.g. Līlasuṃghāṇa, coastal Jade Coast), while some only use the [f] one (e.g. Cami and most of the Far East). For this reason, the phoneme is usually transcribed /f/.

- /ɦ/ may be realized in various ways, including uvular or velar voiceless fricatives, especially when at the end of a word.

- /ʋ/ may be realized as [f] before voiceless consonants; this is NOT reflected orthographically.

- /ʀ/ is often realized as [ʁ] after consonants, especially after coronal stops, and as [ɽ] or [ɻ] adjacent to retroflex consonants. In coda it is usually vocalized to [ɐ̯], except when before a retroflex consonant.

Some allophonic variations not proper of standard Chlouvānem but widespread in many areas:

f is realized as [ɸ] in those few words where it occurs before /p/ (e.g. kafpa (a sardine-like fish) [kaɸpa]) or word-finally (all interjections, such as hųf! "phew!" [ɦṳɸ]); in many pronunciations (notably in Yāmbirhālih, Galiākina, and across Lgraṃñælihaikā diocese, and also increasingly found among young speakers in Līlasuṃghāṇa) it is also realized this way before /u uː ṳ/ (e.g. maifu "enough" [maɪ̯ɸu]).

Not proper of standard Chlouvānem but so widespread it is now by far the most common pronunciation is also the deletion of /j/ and /ʋ/ before /i iː i̤/ or /u uː ṳ/ respectively, e.g. in yinām /jinaːm/ [inaːm] (protection, refuge) or vurāṇa /ʋuʀaːɳa/ [uʀaːɳa] (a kind of small-sized reptile)[3]. This also leads to phonetic hiatuses, like in Kāyīchah /kaːjiːc͡ɕʰaɦ/ [kaːiːc͡ɕʰaɦ] (an insular diocese between Mārṣūtram and Vedren) or the common given name Martayinām /maʀtajinaːm/ [maɐ̯ta.inaːm].

Pronouncing /ʀʲ/ as [ʐ] or [ʑ] is also a fairly common thing across the East and Northeast; it is nearly universal among young people and in certain areas (most notably the area of the Padeikoli Gulf, including most of the diocese of Padeikola, coastal areas of Lågnemba, and the northern third of Hachitama) it is the norm, with [ʀʲ] being found only as a gerontolectal feature. The palatalized stops are also often pronounced with a noticeable sibilant release, especially in the eastern part of the Jade Coast among younger speakers.

The area around Lūlunīkam Lake, including both Līlasuṃghāṇa and Ilēnimarta (except gerontolectally) is also known for shifting /g/ to semivowels in coda position - the aforementioned diocese of Lågnemba is pronounced as [ɴ̆ɔʊ̯nẽ(m)ba] there; the country of Ênêk-Bazá (enægbasā in Chl.) is [enɛɪ̯basaː].

There are also lots of regional variations for /ɦ/ at the end of a word, with a particularly common realization being [χ] (as in e.g. Līlasuṃghāṇa and Galiākina), like lilah /ɴ̆ʲiɴ̆aɦ/ [ɴ̆ʲiɴ̆aχ] (I/(s)he/it/they live(s)).

Vowels - Camiyāṃsai

The vowel inventory of Chlouvānem is fairly large too, consisting of 24 phonemes: 15 monophthongs, 7 diphthongs, and 2 syllabic consonants.

Phonetically, there are also nasal vowels, but they are phonemically /Vɴ/ or (word-finally) /Vn/ sequences. On the contrary, breathy-voiced vowels may phonetically surface as [Vh] or [Vχ] in some contexts (most notably before stops) in some pronunciations — e.g. tąkis /tɑ̤kis/ (a kind of herb) pronounced in Cami as [taxkʲis].

The term for vowel is camiyāṃsa, from cami (great, large, important) and yāṃsa (sound), as these sounds are necessary in building syllables.

| → Backness ↓ Height |

Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Oral | i i ī iː |

u u ū uː | |

| Br.-voiced | į i̤ | ų ṳ | ||

| High-mid | Oral | e e ē eː |

||

| Br.-voiced | ę e̤ | |||

| Low-mid | æ ɛ ǣ ɛː |

o-å1 ɔ | ||

| Low | Oral | a ä2 ā äː2 |

||

| Br.-voiced | ą ɑ̤ | |||

| Diphthongs | Oral | ai aɪ̯ ei eɪ̯ |

oe ɔə̯ | au aʊ̯ |

| Br.-voiced | ąi a̤ɪ̯ ęi e̤ɪ̯ |

ąu a̤ʊ̯ | ||

| Syllabic consonants | ṛ ʀ̩ ṝ ʀ̩ː | |||

Table notes:

- In modern Chlouvānem, the distinction between o and å is purely orthographical.

- Chlouvānem a is a central vowel and is better transcribed as [ä]. However, for simplicity's sake, it will always be transcribed, phonemically and phonetically, as /a/ [a] hereafter.

Chlouvānem vowels have very little allophony, always having values pretty close to their IPA representations' usual positions in the vowel trapeze. As Chlouvānem (and most of its descendants, which are the true native languages for the majority of Chlouvānem speakers) is a syllable-timed language, and stressed and unstressed syllables are barely (if at all) distinguished, unstressed vowel reduction is basically nonexistent.

The most notable instances of vowel allophony are:

- /ɛ ɛː/ lower to [æ æː] before /ʀ/ - e.g. kauchlærīn [kaʊ̯c͡ɕʰɴ̆æʀʲiːŋ] "professor";

- /ɔ/ is realized as a mid or, for some speakers, high-mid vowel ([o̞] or even [o]) when preceding any of l lь r rь c ch j jh - e.g. jålkha [ɟ͡ʑo̞ɴ̆qʰa~ɟ͡ʑo̞ɴ̆kʰa] "cold". It is also realized as [oː] (high-mid and long) word-finally. This is, however, rare, mostly only found in borrowings or Eastern toponyms - e.g. Paramito [paʀamʲitoː] (a city in the Far East);

- /u/ is moderately fronted - usually to [ʉ] - after palatalized consonants and /j/ (explaining why /y/ or similar vowels are usually borrowed as /ju/ or /ʲu/) - e.g. yutia [jʉtʲa] "area, direction"

The variants of Chlouvānem spoken by the Chlouvānem minorities in Kŭyŭgwažtov, Soenyŏ-tave, and other countries of the former Kaiṣamā have acquired, through language contact, the front rounded vowels /y ø/ - they are present in loans from the majority languages of those areas (cf. in Kŭyŭgwaž Chlouvānem köndegura /køndeguʀa/ "mountain road", nüvka /nyʋka/ (a typical dish) < Kŭy. köndŭgŭr, nüvŭk; the latter is known as niuvka /nʲuʋka/ in the Inquisition), as well as in peculiar sound changes from the standard pronunciation (Kŭy.Chl. /y/ for standard /ju/ and /ʲu/, e.g. yutia "area, direction" /(j)ytʲa/).

Prosody

Stress

Stress in Chlouvānem is not phonemic and typically very weak.

In formal Chlouvānem, stress position is, in most cases, predictable, determined by long vowels and verbal roots:

- The last long vowel in a word is stressed, unless it is word-final ē;

- Verbal roots always carry either the main stress or secondary stress (depending on the previous rule);

- In words with no long vowels, the third-to-last syllable is stressed, unless the fourth-to-last is the stressed part of a verbal root;

- Compound words have secondary stress on each vowel that would have primary stress if it were an isolated word, except if immediately preceding another (primarily or secondarily) stressed vowel; in that case, the stress moves one syllable backwards unless it would lead to another such situation of consecutive stress (e.g. */ˌSSˌSˈSS/ → /ˌSSSˈSS/ and not **/ˌSˌSSˈSS/).

- Some noun-forming suffixes, especially for specialized terminology, are always stressed, such as -bida/-buda in chemical elements.

- Final -oe and -ai are always stressed, except when -ai is a plural marker - thus lunai "tea" is stressed on the ending, while kitai "houses" on the first syllable.

Some examples of stress placement:

- dilṭha "desert" [ˈdʲiɴ̆ʈʰa]

- upānāraḍa "seminary" [upaːˈnaːʀaɖa]

- ñulge "to crawl (monodirectional)" [ˈɲuŋge]

- ñogē "(s)he/it crawls" [ˈɲogeː]

- ñuganāja "we crawled" [ˌɲugaˈnaːɟ͡ʑa]

- driturkye "[I've been told that] (it) was done against you" [ˈdʀʲituˤkje]

- švaghṛṣṭrausis "tunnel" [ˌɕʋagʱʀ̩ˈʂʈʀaʊ̯sʲis]

- švaghṛṣṭraustammikeika "tunnel railway station" [ˌɕʋagʱʀ̩ʂʈʀaʊ̯sˌtammʲiˈkeɪ̯ka]

Words with unpredictable stress often have regional variations. For example, tandayena "spring (season)" is stressed as [tandaˈjena] in most of the East and Northeast but as regular [tanˈdajena] almost anywhere else (in this particular case, the irregular stress is actually closer to the etymology, as it is a borrowing from a Toyubeshian compound word).

Intonation

Phonotactics

The maximum possible syllable structure is 「[((C1)C2)C3]」(j)V「(C4(C5))」.

The nucleus is formed by V - which can be any vowel, diphthong, or syllabic consonant - and an optional preceding /j/.

The onset may contain up to three consonants: C3 is notated differently because phonetically there always is one, as phonemically vowel-initial syllables are always pronounced with a preceding [ʔ]. Any consonant bar /N/ can appear in this position; C2 can be any other consonant except aspirated or breathy-voiced stops (with a single exception) or /ʔ/, but, if C3 is a stop, no stop can be in this position. If C3 is /ɴ̆/ , then C2 may be /c͡ɕʰ/. C1 may be a sibilant, /ʋ/, or a nasal agreeing in PoA with the following consonant. Note that ss-, vv-, ll- and lьl- are all valid onsets under these rules.

In codas, C4 may be may be any consonant except /ʔ c͡ɕ ɟ͡ʑ/ or all aspirated or breathy-voiced stops. C5 may be /n m s/, or also one of /t d k g/ if C4 is one of /ɴ̆ ʀ/.

In absolute word-final position, only C4 is possible, and the only possible consonants are /m n nʲ p t tʲ ʈ k s sʲ ɦ ɴ̆ ɴ̆ʲ/. Interjections are an exception, as some other consonants are found there, e.g. hār! "ouch!" [ˈɦaːɐ̯], hųf! "phew!" [ˈɦṳɸ].

Morphophonology

Vowel alternations

Ablaut

Chlouvānem morphology uses a system of ablaut alternations in its vowels, most notably for some verbs, for the ablauting declension of nouns (5h), and for many derivations. Every normal ablaut pattern has a base grade (the one given in citation forms), a middle grade, and a strong grade.

The patterns of regular ablaut are the following:

- i-ablaut: base i or ī — middle e — strong ai

- u-ablaut: u/ū — o (ą) — au

- u>i-ablaut: u/ū — i — au

- ṛ-ablaut: ṛ — ar — ār

A few roots have the so-called inverse ablaut, where the vowels get simplified in the middle grade, and there is no strong grade:

- i-type inverse ablaut: base ya (or ьa) — middle i

- ei-type inverse ablaut: base ei — middle i

- u-type inverse ablaut: base va — middle u

Lengthening

Lengthening alternations, which originate in Proto-Lahob, substitute a vowel with its lengthened form. There are many apparently irregular cases, due to the huge vowel shifts that happened between Proto-Lahob (PLB) and Chlouvānem. Note that PLB *î represents /ɨ/ or /ɨ̯/.

Lengthening as a type of vowel alternation is the so-called diachronic lengthening, as the results are largely determined by what those vowels were in PLB:

- a → ā

- a → ū (PLB *o → *ō)

- i → ī

- i → æ (PLB *ej → *ēj)

- i → au (PLB *aî → *āî)

- u → ū

- e → ьa (PLB *e → *ē)

- e → ai (PLB *aj → *āj)

- o → au (PLB *aw → *āw)

- o → ei (PLB *ow → *ōw)

- æ → ьau (PLB *ew → *ēw)

- oe → ai (PLB *oj → *ōj)

- ṛ → ar

Another, different type of lengthening, is synchronic lengthening, which is a saṃdhi change; it only applies to a, i, u, ṛ, æ, and e, turning them into ā, ī, ū, ṝ, ǣ, and ē respectively.

Vowel saṃdhi

Vowel saṃdhi in Chlouvānem is often fairly logical, though sometimes the results are influenced by Proto-Lahob phonology.

Similar vowels (thus /a i e u ʀ̩/ only diverging in quantity or phonation) merge in these ways:

- short + short = long (e.g. a + a → ā)

- long + short = long (and viceversa) (e.g. ā + a → a)

- oral + breathy-voiced = breathy-voiced (a + ą → ą)

- breathy-voiced + oral = /VɦV/, written with the breathy-voiced character followed by the oral one (e.g. ą + a → ąa)

The only exception to this pattern is the sequence ē + e which becomes ege.

Dissimilar vowels merge in these ways. ṛ and ṝ become semivowels wherever needed, and i and u become y and v before other vowels; ī and ū turn to iy and uv respectively.

Other changes are:

- e and o always continue PLB *aj and *aw regardless of etymology, so when followed by vowels the results are ayV and avV respectively. Similarly, with ai and au the results are āyV and āvV;

- æ and ǣ both become ev and oe becomes en when followed by another vowel;

- All other ones simply turn their second element into the corresponding semivowel (e.g. ei → ey).

- a: a-i → e ; a-u → o ; a-e → ai ; a-o → au

- ā: ā-i and ā-e → ai ; ā-u and ā-o → au

- a or ā and a following long vowel (or æ or å) get an epenthetic y (before ī, ē, æ) or v (before ū, å).

- When preceded by a, other diphthongs get a prothetic y if their first element is front and a prothetic v if it is back. æ turns to ya.

Vowel saṃdhi in vowel-ending verbal roots has a few extra rules — see Chlouvānem morphology § Verbs § Vocalic stems.

Consonant alternations

Palatalizations

Palatalization in morphemes (noted as ь) produces different results depending on the preceding consonant:

- If the preceding consonant has a phonemic palatalized counterpart, the result is the palatalized consonant (e.g. /t/ + ь → /tʲ/)

- Velars shift to palatals (e.g. k + ь → c);

- h + ь → š

- The glottal stop remains unchanged;

- All other consonants get a /j/ glide (written y).

Internal saṃdhi

Note: for simplicity, ь will be treated as a stand-alone consonant in all the following examples.

Saṃdhi assimilations are fairly straightforward, and usually it’s the second consonant in a row the one that matters. The most basic rules are:

- Nasals assimilate to the PoA of any following consonant except for y (no assimilation occurs) and s (all become ṃ, phonetically realized as vowel nasalization).

- All stops assimilate in voicing to a following stop; if the first one is aspirated, then aspiration shifts to the second one. Dentals also assimilate to adjacent (preceding or following) retroflexes.

In stop saṃdhi, a few further changes apart from basic voicing and retroflex assimilation occur. Note that any such combination also applies to aspirated stops and, for dentals, palatalized ones. In voiceless stops:

-pṭ- → -fṭ- ; -pc- → -ṃc-

-tp- → -tt- ; -tc- → -cc- ; -tk- → -kt-

-ṭp- → -ṭṭ- ; -ṭc- → -cc- ; -ṭk- → -kṭ-

-cp- → -cc- ; -ct- → -kt- ; -cṭ- → -ṣṭ- ; -ck- → -šk-

-kp- → -pp- ; -kc- → -cc-

Doubled stops and the combinations -pt-, -pk- , -kt-, and -kṭ- remain unchanged.

Voiced stops mostly mirror voiceless assimilations (doubling saṃdhi already applied - all nasal + stop clusters are underlyingly a geminate stop):

-bḍ- → -ṇḍ- ; -bj- → -ṃj- ; -bg- → -lg-

-db- → -nd- ; -dj- → -ñj- ; -dg- → -gd-

-ḍb- → -ṇḍ- ; -ḍj- → -ñj- ; -ḍg- → --gḍ- → -rḍ-

-j + any other stop, also aspirated ones → -jñ-

-gb- → -mb- ; -gḍ- → -rḍ- ; -gj- → -ñj-

Doubled stops become a nasal+stop sequence; -bd-, and -gd- remain unchanged.

-d(h)n- and -ḍ(h)ṇ- from any origin further assimilate to -nn- and -rṇ- respectively.

h, wherever it is followed by a consonant (apart from ь), disappears, leaving its trace as breathy-voiced phonation on the preceding vowel (e.g. maih-leilē → mąileilē). Vowels change as such:

- i, ī → į

- u, ū → ų

- e, ē, æ, ǣ → ę

- all other monophthongs, or oe → ą

- ai, ei, au → ąi, ęi, ąu respectively.

Sibilants trigger various different changes:

- Among themselves, -s s- remains ss (but simplified to s if the latter is followed by a consonant other than y or ь), but any other combination becomes kṣ (e.g. naš-sārah → nakṣārah).

- ṣ, if followed by a dental stop, turns it into ṭ or ṭh according to aspiration (e.g. paṣ-dhvakām → paṣṭhvakām).

- s or š plus any voiced stop, or ṣ followed by any non-dental/retroflex voiced stop, disappear but synchronically lengthen the previous vowel (e.g. kus-drāltake → kūdrāltake).

- Dental stops followed by ṣ or š result in a palatal affricate (e.g. prāt-ṣveya → prācveya).

Note that the two roots lih- and muh- behave, before consonants (with a few exceptions, e.g. the verbal infinitive), as if they were *lis- and *mus-.

If the first sound which undergoes saṃdhi is already part of a cluster, a few more assimilations may occur. In a nasal-stop + stop sequence, usually the first stop gets cancelled, but nasals do not assimilate entirely to the stop:

- m becomes ṃ;

- Other nasals do not assimilate at all.

Note that the combinations -mpt-, -mpk-, -lkt-, -lkṭ-, -mbd-, -lgd-, and -lgḍ- all remain unchanged; doubled stops are degeminated (like -mpp- > -mp-).

If the sound before the stop sequence is l or r, nothing happens and assimilations are normal. If the sound is a sibilant (note that they cannot precede voiced stops), assimilations are as usual.

Note that a few roots may have internal clusters that would not be permitted in internal saṃdhi. Many of these are part of scientific lexicon and all of them are ultimately borrowings, for example Līšabgin - the name of the sixth planet of the star system Calémere is in.

Doubling saṃdhi

In a few cases of consonant doubling due to saṃdhi, there are irregular results:

- -y y- → -jñ-

- Note that */ajj/ and /aɪ̯j/ are different, as the latter is permitted.

- -v v- → -gv-

- -r r- → -rl-

- any doubled voiced stop (also due to assimilation of other stops) → homorganic nasal + voiced stop (e.g. -b b- → -mb-)

Epenthetic vowels

Epenthetic vowels are usually discussed together with saṃdhi. They are often used in verbal conjugations, as no Chlouvānem word may end in two consonants. The epenthetic vowel used depends on the preceding consonant:

- u is inserted after labials;

- a is used after retroflexes (except ṣ), ɂ, and h;

- i is used after all other consonants, including all palatalized ones.

Note that y, v, and r in these cases turn into the corresponding vowels i, u, and ṛ.

Writing system - Jīmalāṇa

Chlouvānem has been written since the early 5th millennium in an abugida called chlǣvānumi jīmalāṇa ("Chlouvānem script", the noun jīmalāṇa is actually a collective derivation from jīma "character"), developed with influence of the script used for the ancient Kūṣṛmāthi language. The orthography for Chlouvānem represents how it was pronounced in Classical times, but it's completely regular to read in all present-day local pronunciations.

The Chlouvānem alphabet is distinguished by a large number of curved letter forms, arising from the need of limiting vertical lines as much as possible in order to avoid tearing the leaves on which early writers wrote. Straight vertical or horizontal lines are in fact present in a few letters (mostly the rarer ones, such as independent vowels) but they have been written as straight lines only since typewriting was invented. Being an abugida, vowels (including diphthongs) are mainly represented by diacritics written by the consonant they come after (some vowel diacritics are actually written before the consonant they are tied to, however); a is however inherent in any consonant and therefore does not need a diacritic sign. Consonant clusters are usually representing by stacking the consonants on one another (with those that appear under the main consonant sometimes being simplified), but a few consonants such as r and l have simplified combining forms. The two consonants ṃ and ь are written with diacritics, as they can't appear alone. There are also special forms for final -m, -s, and -h due to their commonness; other consonants without inherent vowels have to be written with a diacritic sign called priligis (deleter), which has the form of a dot above the letter.

The combinations lā vā yā fā ñā pā phā bhā are irregularly formed due to the normal diacritic ā-sign being otherwise weirdly attached to the base glyph. There is, furthermore, a commonly used single-glyph abbreviation for the word lili, the first-person singular pronoun.

The romanization used for Chlouvānem avoids this problem by giving each phoneme a single character or digraph, but it stays as close as possible to the native script. Aspirated stops and diphthongs are romanized as digraphs and not by single letters; geminate letters, which are represented with a diacritic in the native script, are romanized by writing the consonant twice - in the aspirated stops, only the first letter is written twice, so /ppʰ/ is pph and not *phph. The following table contains the whole Chlouvānem alphabet as it is romanized, following the native alphabetical order:

| Letter | m | p | ph | b | bh | f | v | n | t | th |

| Sound | /m/ | /p/ | /pʰ/ | /b/ | /bʱ/ | /f/ | /ʋ/ | /n/ | /t̪/ | /t̪ʰ/ |

| Letter | d | dh | s | ṇ | ṭ | ṭh | ḍ | ḍh | ṣ | ñ |

| Sound | /d̪/ | /d̪ʱ/ | /s/ | /ɳ/ | /ʈ/ | /ʈʰ/ | /ɖ/ | /ɖʱ/ | /ʂ/ | /ɳ/ |

| Letter | c | ch | j | jh | š | y | k | kh | g | gh |

| Sound | /c͡ɕ/ | /c͡ɕʰ/ | /ɟ͡ʑ/ | /ɟ͡ʑʱ/ | /ɕ/ | /j/ | /k/ | /kʰ/ | /g/ | /gʱ/ |

| Letter | ṃ | ɂ | h | r | l | ь[4] | i | ī | į | u |

| Sound | /ɴ/ | /ʔ/ | /ɦ/ | /ʀ/ | /ɴ̆/, [ŋ] | /ʲ/ | /i/ | /iː/ | /i̤/ | /u/ |

| Letter | ū | ų | e | ē | ę | o | æ | ǣ | a | ā |

| Sound | /uː/ | /ṳ/ | /e/ | /eː/ | /e̤/ | /ɔ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛː/ | /a/ | /aː/ |

| Letter | ą | ai | ąi | ei | ęi | oe | au | ąu | å | ṛ |

| Sound | /ɑ̤/ | /aɪ̯/ | /a̤ɪ̯/ | /eɪ̯/ | /e̤ɪ̯/ | /ɔə̯/ | /aʊ̯/ | /a̤ʊ̯/ | /ɔ/ (see below) | /ʀ̩/ |

| Letter | ṝ | |||||||||

| Sound | /ʀ̩ː/ |

Some orthographical and phonological notes:

- /n/ [ŋ] is written as l before k g kh gh n. Note that in many local varieties lk lkh lg lgh are actually [ɴq ɴqʰ ɴɢ ɴɢʱ], with the stop assimilating to l and not vice-versa, and thus analyzed as /ɴ̆k ɴ̆kʰ ɴ̆g ɴ̆gʱ/.

Letter names are formed with simple rules:

- All consonants apart from l, r, and aspirated stops form them with CaCas, e.g. s is sasas, m is mamas, b is babas and so on. ɂ is written aɂas.

- Aspirated stops form them as CʰeCas, e.g. bh is bhebas, ph is phepas, and so on.

- l is lǣlas and r is rairas. ṃ is, uniquely, nālkāvi and the palatalizing sign is called hærūñjīma.

- Short vowels are VtV*s, where the second V is a for æ (ætas), i for e (etis), and u for o (otus).

- Long vowels are vowel + -nis if unrounded (īnis, ēnis, ānis), but ū, being rounded, is ūmus. Oral diphthongs all have diphthong + -myas (aimyas, eimyas…); å is counted as a diphthong and as such it is åmyas.

- Breathy-voiced vowels are vowel + /ɦ/ + vowel + s (įis, ąas, ųus, but ęas). Breathy-voiced diphthongs are diphthong + /ɕ/ + as (ąišas, ęišas, ąušas).

o and å

In today's standard Chlouvānem, the letters o and å are homophones, being both pronounced /ɔ/: their distribution reflects their origin in Proto-Lahob (PLB), with o deriving from PLB *aw and *ow, and å from either *a umlauted by a (lost) *o in a following syllable, or, most commonly, from the sequences *o(ː)wa, *o(ː)fa, *o(ː)wo, or *o(ː)fo.

Most Chlouvānem sources, however, classify å as a diphthong: Classical Era sources nearly accurately describe it as /ao̯/, later monophthongized to /ʌ/ or /ɒ/ and merged with /ɔ/ - in fact, most daughter languages have the same reflex for both o and å. A few grammarians think that å was originally the long version of o, but this hypothesis is disputed as å does not pattern with the other long vowels (e.g. o does not lengthen into it because of synchronic lengthening; also it is grouped with diphthongs in the alphabetic order instead of coming just after o, as other long vowels do). Some kind of distinction in the pronunciations of Classical Chlouvānem must have been preserved until early modern times, as both are found in adapting foreign words - usually å transcribes more open vowels than o - cf. the two Holenagic loanwords Hålinaika (Holenagica) - with å for [ɔ] - and lofyun (ṅoifṅ, a vodka-like Holenagic spirit) - with o for [o].

A spelling-based pronunciation distinction (with å being [ɔ] and o being [o(ː)]) has been recently spreading among young speakers in the large metropolitan areas of the Jade Coast.

Notes on romanization

The romanization here used for Chlouvānem is adapted to English conventions, with a few adjustments made to better reflect how written Chlouvānem looks on Calémere:

- Even if the Chlouvānem script uses scriptio continua and marks minor pauses (e.g. comma and semicolon) with a space between the sentences and a punctuation mark with following space, every word is divided when romanized, including particles. The only exceptions to this are compound verbs, which are written as a single word nevertheless (e.g. yųlakemaitiāke "to be about to eat" not *yųlake maitiāke). English punctuation marks are used in basic sentences, including a distinction between comma and semicolon. In longer texts, particularly in the "examples" section, : will be used to mark a comma-like pause (a space in the native script) and ।। will be used for a full-stop-like pause (written very similarly to ।। in the native script).

- As the Chlouvānem script does not have lettercase, no uppercase letters are used in the romanization, except to disambiguate cases like lairē (noun: sky, air) and Lairē (female given name), and for proper nouns written in isolation.

Writing

The Chlouvānem script is almost entirely composed of curved lines as, initially, it was written on leaves with reeds (fålka, pl. fålkai) or brushes (lattah, pl. lattai). With the invention, in the late 5th millennium, of paper (traditional Chlouvānem paper or mirtah is handmade by fibres from various types of wooden bushes; traditional papermaking is still important today as formal handwritten documents are usually written on traditional paper), the use of reeds or brushes often became region-dependant; the reeds of the ñagala plant became the dominant writing tool in most of the plains, as this plant abundantly grows by the river shores; in the Jade Coast, brushes (whose "hair" are actually fibres of wetland plants such as the jalihā) were preferred.

Today, pens (titeh, pl. titiai) are the main writing tool together with graphite pencils (bauteh, pl. bautiai). Non-refillable dip pens were the first to be introduced - an Evandorian invention that was "seized" by the Chlouvānem during the early 7th millennium occupation of Kátra, a Nordûlaki colony on Ogúviutón - and with the advent of industrial papermaking they became more and more popular; fountain pens were evolved from them first in Nivaren, and in 6291 (378512) the first fountain pen manufacturer in the Inquisition opened. Ballpoint pens are, on Calémere, a much recent invention, and first appeared in the Inquisition about forty years ago. They are still not used as much as fountain pens when writing on normal paper.

The traditional fålkai and lattai have not disappeared, as both are still found and used - even if only with traditional handmade paper. Both are commonly used for calligraphy as well as in various other uses: for example, banzuke papers for tournaments of most traditional sports are carefully handwritten with reed pens, as are many announcements by local temples (written with either reed pens or brushes); a newer type of brush pen (much like Japanese fudepens) has proven to be particularly popular even in everyday use (both with traditional and modern industrial paper) in the Jade Coast area - many Great Inquisitors from there, including incumbent Hæliyǣšavi Dhṛṣṭāvāyah Lairē, have been seen writing official document with such kind of pens.

Pens themselves are often artisanal products and in many cases Chlouvānem customers prefer refillable ones; many people have tailor-made sets of pens and almost always carry one with them.

Morphology - Maivāndarāmita

→ Main article: Chlouvānem morphology

Chlouvānem morphology (maivāndarāmita) is complex and synthetic, with a large number of inflections. Five parts of speech are traditionally distinguished: nouns, verbs, pronouns, numerals, and particles.

Most inflections are suffixes, with stem-internal vowel apophony also playing a role. Prefixing inflections are almost exclusively reduplications, though there is a large number of derivational prefixes which play a major role in the language.

Syntax

Constituent order

Like most other Lahob languages, the preferred word order in Chlouvānem is SOV, and the language is almost completely head-final. The word order could however be better defined as topic-comment, but in less common styles it is perfectly possible, thanks to case inflections, to greatly deviate from this standard order.

Note that Chlouvānem terminology typically distinguishes topics as aplidra caṃginutas vs. gu aplidra caṃginutas (or also tadgerenei aplidra caṃginutas or daradhāve aplidra caṃginutas), translated here as "explicit topic" and "unmarked topic" (or "voice-marked topic" or "verb-marked topic") respectively. Explicit topic (aplidra caṃginutas) is understood as a topic marked by the particle mæn.

The subject - whatever agrees with the verb - is usually the topic, but there can be an explicit topic which gets precedence on the subject (i.e. the "unmarked topic" triggered by the verb), as in the third of the following examples:

- yąloe lį ulguta - The food has been bought by me. (food.DIR.SG. 1SG.ERG. buy.PERF-3SG.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.)

- lili yąlenu ulgutaṃte - I have bought food. (1SG.DIR. food-ACC.SG. buy.PERF-1SG.EXTERIOR-AGENT.)

- liliā ñæltah mæn yąloe lį ulguta - My sister, I bought the food [for her]. (1SG.GEN. sister.DIR.SG. TOPIC. food.DIR.SG. 1SG.ERG. buy.PERF-3SG.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.)

The topic-comment structure of Chlouvānem sentences is an analysis that derives from the fact that, in normal speech, the subject always comes first in the sentence except for unmarked topics, or temporal complements topicalized through word order, as in:

- flære prājamne lili lārvājuṣom pīdhvu.

- yesterday. evening-LOC.SG. 1SG.DIR. temple-DAT.SG. go.MULTIDIR.PAST-IND.1S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.

- Yesterday [in the] evening I went to the temple.

Use of the topic

The topic is explicitely marked with mæn if it does not coincide with the subject and does not have any syntactical role in the sentence. Some common structures where explicit topics are always used rank among the most basic sentences:

- lili mæn māmimojendeh fliven "I am 21 (1912, Chlouvānem age)/20 years old (English age)"[5], glossed: 1SG.DIR. TOPIC. nineteenth12.DIR.SG. go.MONODIR-IND.PRES.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.

- lili mæn ñæltion jali "I have two sisters", glossed 1SG.DIR. TOPIC. sister-DIR.DUAL. be-IND.PRES.3D.EXTERIOR.PATIENT. — the verb "to have" is always translated by this construction.

- lili mæn kite dvārmi tītya [jali] "in my house there are eight rooms", glossed 1SG.DIR. TOPIC. house-LOC.SG. room-.GEN.SG. eight. [be-IND.PRES.3P.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.]

Two different topics are also commonly used in contrasts:

- rūdakis mæn tadadrā lili mæn yąlē "[my] husband has cooked, but I eat" - husband.DIR.SG.TOPIC. prepare.IND.PERF.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT. 1SG.DIR. TOPIC. eat-IND.PRES.1S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.

Note how neither "husband" nor "I" agree with the verbs, and note how different formulations change meanings:- rūdakis mæn tēt tadadrā lili mæn yąlē - main interpretation: "as for the husband, he [=someone else, could be the husband's husband] has cooked for him, but it is me who eats" // other possible interpretation: "as for the husband, he [=as before] has cooked him, but it is me who eats / and I eat him [=either of them]".

- rūdakis mæn tadadrā sama lili yąlute "[my] husband has cooked, and I eat" - unlike in the sentence where "lili" is the topic, here it's explicit that the husband cooked for the speaker. The sentence lili mæn rūdakei tadadrā sama yąlute may be interpreted with the same meaning, but the topics are different: with the previous one, the conversation is supposed to continue about the husband; in the second one, it's all about the speaker. Note that the agent-trigger voice in the second verb is of vital importance: the sentence lili mæn rūdakei tadadrā sama yąlu means "it is me my husband has cooked, and [now] he eats me".

- Another possible interpretation of lili mæn rūdakei tadadrā sama yąlute is "[my] husband has cooked for me, and now I eat", which is the same as lili rūdakei takædadrā sama yąlute, but the latter is a plain neutral statement.

Topics also mark context: as a good example, the Chlouvānem translation of Schleicher's fable begins as: yanekai mæn bhadvęs udvī leila voltām mišekte, ūtarnire cūllu khuliu, sūrṣire ūtrau dumbhivu no, lilu kimęe dumbhivu no. Here "horses" is the topic and has no syntactical role in the sentence, as the subject is the agent voltām (sheep) and the three objects are the patients khulias (the pulling one) and two different dumbhivas (the carrying one). The topic makes it clear that these latter are nouns referring to horses - it would still be grammatical to use [...] khuliu yaneku, sūrṣire ūtrau dumbhivu yaneku no, lilu kimęe dumbhivu yaneku no, but the sentence would sound strange to Chlouvānem ears - compare the possible English translation "[...] a sheep saw one horse that was pulling a heavy wagon, one horse that was carrying a big load, and one horse that was carrying a man quickly".

As such, topics usually avoid repetition and anaphora, acting much like folders where different paper sheets (= the sentences) are contained, e.g. nāmñē mæn švai chlǣvānumi maichleyutei, jariāmaile lilah, soramiya mušigērisilīm tora bu sama ñikumi viṣam haloe līlas vi. nenēhu līlasuṃghāṇa ga camimarti haloe gṇyāvire - "talking about nāmñai[6], [they're] animals of the Southern [part of the] Chlouvānem lands, [they] live in seawater but sometimes [they can be found] in tidal lakes too, and another name for [their] cubs is "līlas". From this [name] comes the name of the capital, Līlasuṃghāṇa."

Finally, certain sentences act as answers for different questions due to different implications depending on whether there's an explicit topic or not:

- lili mæn lunai tadarē "I'm preparing tea", topicalized, clearly answers a question like yananū ejulā darire? "what's going on here?".

- lili lunāyu tatedaru "I'm preparing tea" answers yavita lunāyu tatedarē? "who is preparing tea?", with the meaning of "no one but me is preparing tea".

- With a question like yananū sąi darē? "what are you doing?", both become synonyms as they introduce the new topic lili (due to the previous one being yananū? because of patient-trigger voice); the same question in agent-trigger voice, sāmi yananūyu darite?, would be answered with the non-topicalized form.

Definiteness

A topicalized argument, whether explicitely marked (i.e. with mæn) or not, is always understood to be definite. On the contrary, this is not the case for non-topic arguments, whose definiteness, in most cases, has to be understood by context (obviously, this does not apply to words that are semantically definite - e.g. pronouns or proper names).

Common strategies to mark definiteness are:

- Simply adding information to the word (e.g. luvai "(a) market" → saṃryojyami lātimi ubgire ṣarivāṃluvai "the state department store on the approach to central Saṃryojyam"). Again, some ambiguity may still remain;

- Using a determiner - distal nanā "that" is perhaps the most common definiteness marker to resolve ambiguity;

- Explicitely topicalizing the ambiguous argument (not always possible);

- A different solution is to mark indefiniteness: this is commonly done by using either leila "one" or, in colloquial speech, sorasmā "some kind of".

Chlouvānem as spoken in the area around the mid-course of the Lāmiejāya river (the central Plain: roughly the whole of the diocese of Raharjātia, most of Jolenītra, Daikatorāma, Vādhātorama, and Namafleta, and parts of Mūrajātana, Perelkaša, Ryogiñjātia and far northern Sendakārva) does have a definite article used with non-topicalized arguments, which is actually the repurposed archaic demonstrative ami (still used as "this" in Archaic Chlouvānem). It declines for case, but not number, mostly following the pronoun declension (that is, exactly as tami without the initial t- except for the accusative (amu) and ergative (amye)).

Noun phrase

Non-triggered arguments

Non-triggered arguments require a specific case to distinguish their role when they're not triggered by the voice:

- Patient → (transitive verbs) accusative case; (intransitive and interior verbs) essive case

- Agent → ergative case

- Benefacted → direct + nali

- Antibenefacted → direct + fras

- Location → locative case

- Instrument → instrumental case

- Dative argument → dative case

Stative cases as nominal tense

The three stative cases of Chlouvānem (translative, exessive, essive) express nominal tense in certain situations, most notably in copulative sentence, where the translative case conveys a future meaning and the exessive a past one:

- lili rahēllilan — I am a will-be-doctor = I am studying in order to become a doctor

- liliā kaleya mæn gu ninejñairau ša nanū aveṣyotārire lallāmahan camimurkadhānan gīti — as for my best friend[7], I could not believe it, that she was the Great Inquisitor-elect (note the use of the highly respectful (not translated) formula "Her Most Excellent Highness, the Great Inquisitor").

- tami tamiāt šulañšenat — he is her former husband.

The expression of tense is also notable when the expression of state refers to a cause; this is particularly common with the exessive and essive cases:

- saminat tamiā ḍhuvah — having been a child (lit. "as a former child", "from being a child"), (s)he remembers that.

- lūlunimartyęs nunūt dældāt tarliru — being from Lūlunimarta, I understand that language. Note that nunūt dældāt here is exessive case but only because it's an argument of the verb tṛlake, without implying tense.

- bunān samin pa maišildete — as he's going to be a father (lit. "as a will-be-father"), he's learning about children.

Note that, tense is relative to the main verb.

Miscellaneous uses of cases

Purpose may be expressed not only with a subjunctive verb, but also with either a translative or a dative noun.

Translative case is used generally with a purpose directly affecting the trigger:

- murkadhānan kaminairīveyu. "I am studying [in order to become] an Inquisitor."

- tąsь lā nadaidanan peithegde. "(s)he is going out with him/her to get to know him/her."

Dative case is used generally when the purpose is something else, or is the result of a subsequent (unstated) action:

- maivnaviṣye maivasām khloyute. "I am searching in the dictionary [in order to find] the words."

- kǣɂūvai mayābyom rāmiāhai. "Plums are harvested for wine." (Wine is not the direct result of harvesting, thus dative is used instead of translative).

Ablative case is used in order to state comparisons:

- dāneh dulmaidanų nanū lalla. "Dāneh is taller than Dulmaidana."

- faliā ñæltah tąu chlǣcæm pūnē. "Your sister works better than him/her."

- nenē naviṣya yaivų nanū ñæñuchlire. "This book is the most beautiful." (literally "more beautiful than all")

It is also used as reason when it's an abstract noun:

- kairų hånyadaikirek. "(s)he was happy for love."

- maidaudių ḍūkirek. "(s)he died because of his/her ambition."

Possession may be also expressed with the genitive case (topic marking is the most common way, but in some cases this may be needed syntactically; there is a verb cārake translating as "to have, possess", but it's fairly literary and high-styled). "To be" may or may not be present:

- kvyāti giṣṭarire lalāruṇa (vi) "The hero has a young lalāruṇa." (literally "of the hero is the young lalāruṇa (the lalāruṇa that is young)")

- pogi gu cūllanagdha "My village does not have a velodrome." (literally "of my village is no velodrome")

Verb phrase

Use of tenses: Past vs. Perfect

Past and perfect are the two Chlouvānem (morphological) tenses that are used to refer to past actions. Their meanings may be summarized this way:

- The past tense always refers to the past, but it isn’t always perfective;

- The perfect “tense” is always perfective, but it isn’t always past - and when it does, it has an impact on the present.

These theoretical meanings may be translated into practice as this: the past is most commonly used to express something that happened in the past and does not influence the present, or it is not meaningful to the time of the action.

- tammikeika flære lį yųlekrā.

- train_station.DIR.SG. yesterday. 1SG.ERG. eat-IND.PAST.3S.EXTERIOR-LOC.

- Yesterday I ate at the station.

- palias jāyim junirek.

- face.DIR.SG. girl.DIR.SG. paint-IND.PAST.3S.INTERIOR.

- The girl painted her [own] face.

In an appropriate context, however, the same verb form can carry an imperfective meaning:

- tammikeika flære lį yųlekrā væse, nanā tammi tadāmek.

- train_station.DIR.SG. yesterday. 1SG.ERG. eat-IND.PAST.3S.EXTERIOR-LOC. while. , that.DIR. train.DIR.SG. arrive-IND.PAST.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR

- Yesterday I ate at the station.

- jāyim mæn palias junirek, mbu nenichladireti meinei muṣkemālchek.

- girl.DIR.SG. TOPIC. face.DIR.SG. paint-IND.PAST.3S.INTERIOR. , but. hurry-SUBJ.IMPF.3S.INTERIOR. mother-ERG.SG. ask-INF-run.MULTID-IND.PAST.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR.

- The girl was painting her [own] face, but her mother kept asking her to hurry.

Generally this imperfective meaning is assumed by other words in the sentence, usually væse (while), but commonly also mbu (but) with a related sentence understood to be imperfective. Out of context, imperfective past is usually expressed with an analytic construction:

- tammikeika flære lį yųlītirā lā ē.

- train_station.DIR.SG. yesterday. 1SG.ERG. eat-SUBJ.IMPF.3S.EXTERIOR-LOC. with. be.IND.PAST.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR.

- Yesterday I was eating at the station.

The main use of the perfect is expressing something that happened in the past but is still impacting the present; this is a difference very similar to the one between simple past and present perfect in English, and as such the perfect is usually translated that way. Compare, for example:

- palias jāyim junirek - “the girl painted her [own] face”. Past tense here expresses a generic action: the girl may have painted her face ten years or five minutes ago, but that is irrelevant to the situation. In this particular sentence, the girl’s face may be understood to have now been cleaned, or that she may have cleaned and painted her face again many times - but, actually, whether she did or didn’t is now irrelevant. The actual time when she did it only becomes relevant if it is expressed (e.g. palias jāyim flære junirek “the girl painted her [own] face yesterday”) and then it is understood that her face isn’t painted anymore.

- palias jāyim ujunirā - “the girl has painted her [own] face”. Perfect “tense” here focusses not on the action, but on its result. The girl finished painting her face, and it may be seen that her face is still painted - when she did is still irrelevant, but it happened sufficiently close in time that the result of that action may still be seen.

The Chlouvānem perfect, however, has a broader use than the English one, compare:

- flære dašajildek - “yesterday it rained”. Past tense, implied meaning is that there’s nothing that may indicate that yesterday it rained, or it doesn’t influence the speaker in any way.

- flære dašejilda - *yesterday it has rained. Perfect tense; while wrong in English, this construction is possible - and, in fact, is frequently heard - though it often only makes sense in a broader context. For example, in a sentence like “yesterday it rained and the path collapsed, so we [two] can’t walk there”, English uses both times a simple past, while Chlouvānem uses the perfect, as the path is still not walkable due to the rain: flære menni dašejilda līlta viṣustura no, āñjulā gu pepeithnāyǣ ša.

Note that the “impact on the present” meaning and the use of evidentials are independent from each other. Using a first inferential, for example, does not change the implications given by the use of perfect or past, though the actual interpretation is often heavily dependent from context:

- palias jāyim junianerire - “apparently, the girl painted her [own] face”. Past tense: it can be assumed that the girl painted her own face sometime in the past; e.g. the girl is now painting her face, and given the way she does it, it’s reasonable to believe it’s not her first time.

- palias jāyim ujunianerirā - “apparently, the girl has painted her [own] face”. Perfect “tense”: it can be assumed that the girl now has a painted face, but the speaker has not seen her; e.g. in her room there are face painting colours open or that look like they’ve been recently used.

Second inferential changes the speaker’s deduction, but not the implications given by tenses:

- palias jāyim junianuyere - “apparently, the girl painted her [own] face, but probably didn’t”. Past tense: as before, but while she, or something she did, had made the speaker believe she had already painted her face at least once in the past, the way she’s doing it makes think that she probably never did.

- palias jāyim ujunianuyerā - “apparently, the girl has painted her [own] face, but probably didn’t”. Perfect “tense”: as before; highly dependent on context. For example, there are face painting colours out of place, but it’s unlikely she did paint her face - e.g. it may not be a logical time to do it, or too little colour seems to have been used.

The Chlouvānem perfect is however also used where English would use past perfect or future perfect, as the “impact on the present” is understood to be on the time the main action in the sentence takes place, thus something that happened earlier is considered to have an impact on it:

- tammikeika flære lį uyųlarā, utiya nanā tammi tadāmek.

- train_station.DIR.SG. yesterday. 1SG.ERG. eat-IND.PERF.3S.EXTERIOR-LOC. , then. that.DIR. train.DIR.SG. arrive-IND.PAST.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR.

- I had [already] eaten at the station yesterday when the train arrived.

- tammikeika lį uyųlarā, utiya nanā tammi tafluniṣya.

- train_station.DIR.SG. 1SG.ERG. eat-IND.PERF.3S.EXTERIOR-LOC. , then. that.DIR. train.DIR.SG. arrive-IND.FUT.3S.PATIENT.EXTERIOR.

- I will have [already] eaten at the station when the train arrives.

Note that in the latter example, English uses future perfect and present simple respectively, while Chlouvānem uses perfect and future; the future in the second clause is necessary to give the future perfect meaning to the first one.

Still, note that out of context both pluperfect and future perfect may be expressed analytically, by using the perfective subjunctive plus lā (with) and the past or future tense of gyake (to be).

A notable exception to this use is with so-called “chained actions”, when the second one is a direct consequence of the first and the first one is usually still ongoing; the second one is therefore only a momentane happening inside the broader context of the first, and thus the choice between present and past is once again dependent on the impact on the present. Note that in such cases the two verbs are usually connected with no instead of sama. Compare:

- dašajildek līlta vīkṣṭāṭ no - “it rained, and the path collapsed”. Past tense: the path has since been repaired and it is walkable.

- dašejilda līlta viṣustura no - “it has rained, and the path has collapsed”. Perfect “tense”: the path is not walkable due to it having collapsed.

Both the past and the perfect can be frequentative:

- marte mīmišviyek kite lįnek no - "(s)he kept being seen in the city, and [therefore] remained at home" ((s)he has since gone out of home).

- marte memīšveya kite ilįna no - "(s)he has kept being seen in the city, and [therefore] she has remained at home" (actual meaning dependent on a broader context, e.g. āñjulā tatantefuflonaiṣyes "you can find him/her there" (potential agent-trigger future of tatatflulke (ta-tad-flun-) "to find")).

In narrative, it is common to use the perfect for a completed action and the (aspectless) past for an action that begins immediately after (examples taken from the excerpt "A festive day", among the example texts on this page):

- naina mæn ~ dvārmom nañamṛca kautepuglek - "Naina ranPERF into the room [and] woke [us] upPAST"

- hālkenīs yanomųvima keikom namṛcñāja - "we jumped outPERF of the beds [and] ranPAST into the yard"

- tainā mæn yanelīsa pārṇami nacu ilakakte nainęs lā fuldek - "Tainā came outPERF [of the washing room], got dressedPERF for the day, [and] playedPAST with Naina"

Compare this other example from the same text where the last two verbs are both in the past because they're contemporaneous actions:

- nilāmulka mæn maildvārmom nañelīsa tainā lili no ṣveye primirtaram ñumirlam - "Nilāmulka enteredPERF the washing room [and] me and Tainā sitPAST behind the wall [and] waitedPAST"

The optative mood

The Chlouvānem optative has two main uses: as an expression for wishes (in exclamations), and as a form roughly corresponding to the English verbs "should" and "ought to". Due to these meanings, it is also a common form of polite imperative.

The use of optative forms, given this explanation, is fairly clear; some examples follow.

- tami paṣalīleinē! "may (s)he survive!"

- pū glidemæh āñjulā jeivau! "if only I had been there!"

- samin nanǣ dvārme gu tiaineran ša. "the kids shouldn't stay in that room."

- yąlenų ānat kārvātiu valdånьdreinite. "after a meal you ought to burn (lit. "to turn on") incense[8]."

- lālis yacē nami, tamaireinildṛši spa. "please sit down."

The subjunctive mood

The subjunctive mood has a variety of uses, most commonly when followed or introduced by a certain particle. The bare subjunctive, however, has a supine meaning:

- šuteitieldā, yaivei tamišīti. "it has been put there for everybody to look at it."

- luvāmom dāmek yambrānu lgutītite. "(s)he went to the market to buy pears."

Some verbs, such as nīdhyuɂake (to call for), usually require the subjunctive:

- nītedhyuɂek karthāgo bīdrīti. "(s)he called for Carthage to be destroyed."

The verbs for "to study" (pāṭṭaruke, pāṭṭarudṛke, kaminairīveke) and "to learn" (interior forms of mišake; nairīveke) only need a supine-meaning subjunctive when they mean "in order to know something, in order to be able to". With the meaning "in order to become something", a noun in translative case is used:

- fildenī āndṛke munatiam ejulā kaminairīveyu. "I study here in order to be able to create games."

- fildenāndarlilan kaminairīveyu. "I study in order to become a game creator."

Verbs like lelke (to choose (stem: len-)), its synonym vāgdulke (vād-kul-), or mulke (to know how to (stem: mun-, highest grade ablaut in the present) can use invariably the subjunctive or the infinitive; usually, the subjunctive is used when there is a stated subject that is different from an impersonal phrase:

- tami jilde maunalieh. "we know how to do it."

- yakaliyātamei āndrīti elena. "it has been chosen to have it built by Your honorable company."

- tami šubīdṛke lenanājate. "we decided to tear it down."

Positional and motion verbs

→ See Chlouvānem positional and motion verbs.

Positional and motion verbs are a semantically and syntactically defined category of Chlouvānem verbs that constitutes one of the most complex parts overall of Chlouvānem grammar, with similar (though often more simplified with time) in all other Lahob languages; the Chlouvānem system is essentially the same as the one reconstructed for Proto-Lahob.

Positional verbs (jalyadaradhūs, pl. jalyadaradhaus) translate verbs such as "to stay", "to be seated", and "to lie", (as well as their middle and causative forms) with prefixes that are semantically comparable to English prepositions. Motion verbs are more similar to English, being satellite-framed (the satellite, in the Chlouvānem case, being the prefix), but there is an added complexity because motion verbs can be monodirectional (tūtugirdaradhūs, -aus) or multidirectional (tailьgirdaradhūs, -aus), and most verbs come in pairs, each member of a pair being used in different contexts.

Relative clauses

Chlouvānem relative clauses are nonreduced and work exactly the same way as adjectival verbs do: both clauses are independent, with optionally an i particle (which combines with the preceding verb) for disambiguation. Time, place, and similar things are expressed with a distal correlative (see the table of correlatives).

The structure is thus as follows:

- sēyet nanā jāyim mešē liliā buneya.

- 2S.ERG. that.DIR. girl.DIR.SG. see-IND.PRES.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT. 1S.GEN. older_sister.DIR.SG.

- That girl you see is my older sister.

The i particle may be added after mešē, contracting to mešei.

Other examples:

- mešute gu tarliru ša.

- see-IND.PRES.1S.EXTERIOR-AGENT. NEG- know-IND.PRES.1S.INTERIOR. -NEG.

- I don’t know/understand what I see.

- liliā ñæltah līlekhaitom tesmudhiṣya ātiya lēyet lairkeikom khlavasiṣya.

- 1S.GEN. sister.DIR.SG. Līlekhaitē-DAT. depart_with_plane-IND.FUT.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT. then. 1S.ERG. airport-DAT.SG. go_with.IND.FUT.3S.EXTERIOR.PATIENT.

- When my sister takes the plane to Līlekhaitē, I will go with her to the airport.

- tū kulekte ātmena gu tarliru ša.

- 3S.ACC. say-IND.PAST.3S.EXTERIOR-AGENT. that_reason. NEG- know-IND.PRES.1S.INTERIOR. -NEG.

- I don’t know why (s)he said it.

The same strategy is used for attributes — kamilire fluta "blue bag" or "bag that is blue", including participial-like structures such as the following ones:

- lilei priemęlia fluta - the bag which has been given back by the person (literally: "by the person it has been given back, the bag")

- flutu pritēmęlia lila - the person who has given back the bag

- flutu dhurvāneiti prikevemęlia lila - the person for whose benefit the bag has been given back to the police

- flutu ītulom prituremęlia lila - the person for whose misfortune the bag has been given back to the thief

- håmarṣūvī nīpanotē fluta - the bag in which the keys lie

- flutu priūsyemęlia lila - the person who has been given back the bag

- flutua demie maihei priūsyemęlia lila - the person who has been given back the bag by his/her own daughter

- ītulu lāṇṭaṃrye lilei utugamǣ fluta - the bag with which the thief has been hit on the head by the person

Such constructions can also be used where English uses gerundive constructions:

- flutu demie maihei priūsyemęlia lila hånyadaikirek. - the person, having been given back the bag by his/her own daughter, was happy.

- ālīce guṃsek liliā pamih uyūṭarau rileyekte. - my finger, having been cut that way, needed an operation.