単亜語

| Dan'a'yo | |

|---|---|

| 単亜語 | |

| |

| Writing | w:新字体 |

| Region: | w:East Asia |

| Genders: | 0 |

| Cases: | 0 |

| Proto-language: | w:Sinosphere |

| Typology: | Analytic |

| Word-Order | SVO |

| Languages: | w:Korean language,

w:Japanese language, w:Chinese language w:Vietnamese language |

| Population: | 1500 million |

| |

|

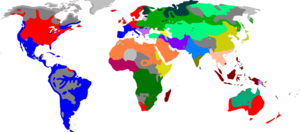

Africa: SEDES • Middle Semitic • Kintu • Guosa Central Asia: Jalpi • Caucas • Zens • Dravindian • Neo-Sanskrit Europe: Intralingua • Folksprak • Interslavic • Balkan • Samboka Far East: Dan'a'yo • IM • MSEAL | |

Anthropology

Dan'a'yo returns a shared world of the w:East Asian cultural sphere. The ancient w:Imperial examination (

The language communities that Dan'a'yo seeks to incorporate and unify are Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and to a lesser extent, Vietnamese. Korea and Japan have long formed a sprachbund already, and have many calques and grammatical features in common. They even share some vocabulary. (There are those who think they are genetically related, but that has yet to be conclusively proven.) There will be some additional similarities that must occur with southern Sino-Tibetan languages, but that is not a design goal, merely a consequence. There is no proto-language which all our source languages are supposedly descended from. Our ancient form is Classical Chinese, which is well-known and actually exists in documented form.

Phonologies

Korean has a tense/lax system which is completely unknown to the others in the region. Japanese alone contrasts voiced/unvoiced, instead of aspirated/un-aspirated like the rest. The Chineses have contour tones which are much more complicated than JK pitch accent system. All these features must be ignored, as they have no common parallels. Korean has the most robust phonotactics, with CVC syllables allowing many kinds of consonants in the coda, and Cantonese is a close second. Mandarin has only /n/ and /ŋ/ in the coda. Japanese has gemination – which doubles the next voiceless stop, and a homorganic nasal – which can be /m/, /n/, or /ŋ~ɴ/. In short, a rough compromise is possible, with everyone having to learn something, but nothing like what it would take to learn any other language.

Chinese characters have roughly stayed the same for 1,000 years, but some changes have crept in. The most overreaching is the Simplified characters of mainland China, which are utterly dependent upon Mandarin pronunciation and incompatible with the region as a whole. Korean uses ancient versions, which are sometimes grossly out of date and far more obtuse than what others write. A strong, compromise position is to use Japanese Shinjitai, which has mild updates and simplifications to some characters. A phonetic alphabet is hard to agree upon. Japanese hiragana and katakana are not capable of indicating precise coda consonants. Korean Hangǔl is generally well-suited, though one coda off-glide requires abuse of notation.

Multilingual dictionary sources – such as Wiktionary – already document much of the vocabulary in common across the Far East Asian region. Selection of a limited number of Chinese characters must involve a kind of voting process. Japan is well-positioned to begin education of Dan'a'yo at an early age. Korean politics are unfortunately embroiled over a senseless debate about the national character of learning Chinese characters, a holdover from the war and the product of pride. Chinese standard education frowns upon teaching grammar, but there is a revival of Classical education. Many teaching resources are still needed.

Phonology

単亜語 has 5 vowels and 16 consonants.

| Consonants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |

| Nasals | ㅁ /m/ | ㄴ /n/ | ㅇ /ŋ/ | |

| Aspirates | ㅍ /pʰ/ | ㅌ /tʰ/ | ㅊ /t͡ɕʰ~cʰ/ | ㅋ /kʰ/ |

| Voiced | ㅂ /b~p/ | ㄷ /d~t/ | ㅈ /dʑ~tɕ/ | ㄱ /g~k/ |

| Fricatives | ㅅ /s ~ ɕ/ | ㅎ /h ~ ɦ ~ x/ | ||

| Sonorants | w /w/ | ㄹ /l ~ ɾ/ | y/j/ | |

(W and Y are achieved with special glyphs.) While there is a great deal of consonantal allophony (see the table), every language's speaker will experience some sounds as difficult, especially in achieving consistency.

| Vowels | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | |

| High | 이 /i ~ ɪ/ | 우 /u ~ ɯ/ | |

| Mid | 어 /e ~ e̞/ | 오 /o ~ o̞/ | |

| Low | 아 /a ~ ä/ | ||

Again, a great deal of tolerance is required when listening to others. Non-Mandarin speakers will have the hardest time being patient with Chinese vowels, but accents are part of being international! Long vowels do not exist, per se, even if the Latin transcription appears as though they do. 웃/'uu and 의/'ii are actually said as /uʊ/, /uu̵/, or /uǝ/; and /iǝ/ or /ii̵/ respectively. Additionally, there is an epenthetic vowel, which varies considerably among the target nations. It's written as 으 and transcribed as ǔ, and it may be pronounced /ɯ/, /ɯβ/, /ɨ/, /ǝ/, or /ʊ/. This is only used in transcribing foreign words.

Tone/Prosody

Even for speakers of a tonal language, learning a new set of tones is difficult. Therefore, syllabic tones are not phonemic in Dan'a'yo. However, to easy listening and to distinguish the boundaries between words, the following intonation principles are used:

- The main (finite) verb of an utterance should be the highest point of it.

- The head of a phrase should be the highest point of it.

- The main vowel of a syllable should be the highest point of it.

- The first character's syllable of a compound word should be the highest point of it.

This can be helpful in distinguishing

Pitch cannot be used to indicate a question. Please use the SFP

Phonotactics

Maximally, a Dan'a'yo syllable consists of an ONSET consonant, an ON-GLIDE, a VOWEL, and an OFF-GLIDE or CODA CONSONANT. The ONSET can be ø or any consonant except ŋ, the ON-GLIDE can be ø, y, or w, the VOWEL must exist, and the CODA CONSONANT can be ø, y, w, b, d, g, m, n, or ng. Each syllable has no effect upon the next.

For a complete chart of all possible Hanmun syllables, see 単亜語/Syllables.

Syntax

Like Chinese and Vietnamese (and unlike Japanese and Korean), 単亜語 is SVO, subject-verb-object. The subject of an intransitive verb and the actor of transitive verb come early in the sentence (before the verb), and the accusative argument must come after. There are no particles to mark subject or object.

| Relationship | Particle | English | Mandarin | Cantonese | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | as for | - | - | は wa | 은/는 (n)ǔn | cái | ||

| Vocative | O | ya | yeo | 야 | ||||

| Dative | to | - | - | に | 에게 | đến | ||

| Genitive | of | 的 | 嘅 | の | 의 | của | ||

| Instrumental | by | 用 | 用 | で | 로/으로 | |||

| Locative | in, on, at | 在 | 喺 | に | 에 | |||

| Comitative | together with | |||||||

| Assoc. Pl. | et. al. | 們 | 哋 | たち | 들 | tôi/tao/ | ||

| Perfective | -ed | 了 | 咗 | た/だ | 았/었 | đã | ||

| Progressive | -ing | 아/어 | ||||||

| Nominalizer | -ed | |||||||

| Nominalizer | -ing | こと | ~기, ~는 것, ~음/ㅁ | |||||

| Adnominalizer | の | 의 | ||||||

| Adverbializer | -ly | 地/一點/得 | く/に | -히/-게 | ||||

| NP And | and | 和 hé | 及 kap6 | と | 와/과 | và | ||

| VP And | and | 以及/yǐjí | そして | 그리고 | và | |||

Sentence Final Particles

Pronouns

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Casual | First | ||

| Second | |||

Classifiers

Counting is not done with numerals as adjectives before the noun phrase, but with special classifiers + numerals after the noun phrase, as adverbs.

| Classifier | Use |

|---|---|

| people (general) | |

| people (polite) | |

| machines (computers, cars, etc) | |

| animals (all animals, worms, fish, horses, etc.) | |

| books, magazines, etc. | |

| cups of some drink | |

| flat objects (pizzas, paper, etc.) | |

| long objects (pencils, noodles, etc.) | |

| periods of time (seconds, years, ages, etc.) | |

| bundles (groups, bouquets, bales, etc.) | |

| 個 ka | anything else |

Plants, animals and things that may have hanji beyond our corpus or are nation-specific, should be spelled out phonetically, but appended with a "determiner", a hanji that shows what class of being the creature is. This is helpful, as it gives a hint to those unfamiliar with the being.

| Determiner | Use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| name, endonym | ||

| amphibians | ||

| birds | Japanese quail ウズラ = 우주라 ( | |

| fish | ネコギギ = 너코기기 ( | |

| invertebrates, bugs, snakes | ||

| mammals | ||

| reptiles | ||

| flowers | Venus flytrap = 디오나어아 ( | |

| grass, herb | basil = 바지르 ( | |

| trees, bushes | redwood = 서쾨아 ( | |

| clothes | きもの = 키모노 ( | |

| meals, food | 비빔밥 ( | |

| device, tool | iPad = 애파드 ( | |

| idea, movement | ubuntu = 우분투 ( | |

| building | Burj Khalifa = 부르즈 카리파 ( | |

Demonstratives and indefinite

Demonstratives occur in the

| Proximal ( |

Medial ( |

Distal ( |

Interrogative ( |

Cyclic ( |

Existential ( |

Universal ( | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Act ( |

this |

that |

yon |

what |

for each |

something |

everything |

| Object ( |

this one |

that one |

yon one |

which |

for each one |

something |

everything |

| Person ( |

him/her |

him/her |

him/her |

who |

per person |

someone |

everyone |

| Place ( |

here |

there |

yonder |

where |

per place |

somewhere |

everywhere |

| Time ( |

now |

then |

that other time |

when |

per time |

sometime |

always |

| Manner ( |

in this manner |

in that manner |

in that other manner |

how |

each manner |

somehow |

in all ways |

| Quantity ( |

this many |

that many |

yon many |

how many |

per quantity |

some amount |

all amounts |

| Kind ( |

this kind |

that kind |

yon kind |

what kind |

totally |

some kind |

every king |

Lexica

Dan'a'yo forcibly limits the number of Chinese characters which can be used to around 3200. This is done by only drawing characters from the standard lists of each country (CJK). Characters that are inventions of anyone country as banned. Characters which are not common or strictly necessary are banned. Similar characters are sometimes lumped together, especially if they are obscure. The "weight" of any character is determined by its place in the following national lists:

- China: The HSK (漢語水平考試). There are six sub-section to this list.

- Japan: The 常用漢字 (Jōyō), including 6 grades, a high school list, plus a name list. Most every character is allowed. We also include Extended Shinjitai.

- Korea: The 敎育用基礎漢字 (교육용 기초 한자), including middle school, and high school lists. The list of characters allowed in names is profligate (as more than one scholar has noted) and is often curtailed.

Each character is like a letter and may or may not be a word on its own. Characters which are not words have a two-character word which is deemed to be the same as the solo character. Every character – in theory, all 45,000 Chinese characters which have ever been used – is assigned to one of five categories:

- Common - (常用字) These 1931 characters are the bedrock of the language and may be used freely. They are further divided into six levels, solely for the purpose of aiding learning.

- Variants - (異体字) These are disallowed ways of writing a given character, mainly arising from national and font differences. It is also a way of appropriating many, many additional characters into simply being aliases of established characters. Only the Shinjitai, listed form of the character is "correct".

- Advanced (先進字) These 276 characters are useful for situations when Dan'a'yo needs to function like a native language, and speak on any topic, but are considered extra learning. Their usage is restricted in international and cosmopolitan situations, which are intended to be maximally inclusive.

- Name (名字) These are 385 characters that detail the specific names of species and municipalities, which must always be safeguarded with a determiner, which identifies them as such.

- Illegal (違法字) Finally, there are some characters which are the provenance of one country only, and are therefore banned in Dan'a'yo. There are about 372 of these, though most have been out of circulation for centuries, if they ever were.

As in every language, finding Chinese character is difficult. There is the ancient system of Radicals, but it can sometimes feel arbitrary where a character is recorded. A new system – which Dan'a'yo embraces – is the SKIP method of looking up characters.

Word lists

Sample

Classical Texts

- 四書

- 五経

- 西遊記

- 単亜語/道徳経 - The Tao Te Ching, or 닷둑겅

- 単亜語/孫子兵法 - Sun Tzu's Art of War

- 単亜語/荘子 - Zhuangzi

- 単亜語/説苑, 刺客列傳, 列女傳

Modern

- 単亜語/218 sentences - Sentences to test syntax

- 単亜語/英雄 - Hero move subtitles

- 単亜語/宣言書 - Korean Declaration of Independence

- 単亜語/玉音放送 - The Emperor's broadcast ending WWII

- 単亜語/出身論 - "On Class Origins" is an article by Yu Luoke and published in January 1967 in the Journal of Middle-School Cultural Revolution.

- 単亜語/射鵰三部曲 - The Condor Trilogy by 金庸

Links

References

Bibliography

Linguistics

- Holm, John A. Pidgins and Creoles: Volume 1, Theory and Structure . Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988-1989.

- ---. Pidgins and Creoles: Volume 2, Reference Survey . Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988-1989.

- McWhorter, John. Language A to Z. Columbia University. The Great Courses, 2013. CD and booklet.

Chinese

- Kroll, Paul W. A Student's Dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese. Bilingual ed. Amersfoort, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Pub, 2014.

- Miller, Roy A. Dictionary of Spoken Chinese. Taipei: Mei Ya Publications, 1966

- Rouzer, Paul. A New Practical Primer of Literary Chinese. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2007.

Japanese

- Vaccari, Orsete, and Mrs Enko Elisa Vaccari. Complete Course of Japanese Conversation-Grammar (Entirely Reset, Greatly Enlarged) 24th Edition. Japan: Dai Nippon Printing Company, 1973.

Korean

- Martin, Samuel E. Reference Grammar of Korean: a Complete Guide to the Grammar and History of the Korean Language. Revised, ed. Clarendon, VT: Tuttle Publishing, 2006.

- 新活用玉篇. Seoul, Korea: Dong-a Publishing and Printing Co., 1975

Language Construction

- Okrent, Arika. In the Land of Invented Languages: Adventures in Linguistic Creativity, Madness, and Genius. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2010.

- Rosenfelder, Mark. The Language Construction Kit. Chicago: Yonagu Books, 2010.

- ---. The Planet Construction Kit. Chicago: Yonagu Books, 2010.

- ---. Advanced Language Construction. Chicago: Yonagu Books, 2012.

- ---. The Conlanger's Lexipedia. Chicago: Yonagu Books, 2013.