|

|

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| {{Short description|International auxiliary language created by IALA}} | | {{Infobox Universal Language |

| {{About|the [[International auxiliary language|auxiliary language]] created by the [[International Auxiliary Language Association]]}}

| | | color = #0B24FA |

| {{Distinguish|ApI Interlingua|Interlingue|Interlanguage|Interlingual machine translation}}

| | | name = Interlingua |

| {{Use British English Oxford spelling|date=December 2010}}

| | | altname = Interlinguia |

| {{Multiple issues|

| | | Writing System = Latin |

| {{merge from|Free word-building in Interlingua|discuss=Talk:Interlingua#Merger proposal 22 June 2020|date=June 2020}}

| | | region = Romance-speaking world |

| {{merge from|History of Interlingua|discuss=Talk:Interlingua#Merger proposal 22 June 2020|date=June 2020}}

| | | genders =2 |

| | | cases = 0 |

| | | alignment = Nominative-Accusative |

| | | proto = [[w:Vulgar Latin]] |

| | | Type = Fusional |

| | | word-order = SVO |

| | | child1 = [[w:Portuguese language]], [[w:Spanish language]], [[w:Italian language]], [[w:French language]] |

| | | population = 1200 |

| | | flag =Flag of Interlingua.svg |

| }} | | }} |

| {{Infobox language

| |

| |name=Interlingua

| |

| |nativename=''interlingua''

| |

| |pronunciation= {{IPAc-en|ɪ|n|t|ər|ˈ|l|ɪ|ŋ|ɡ|w|ə}}; IA: {{IPA-art|inteɾˈliŋɡwa|}}

| |

| |speakers=1,500 of the written language

| |

| |date=2000

| |

| |ref=<ref name="Fiedler">{{cite journal|first1=Sabine|last1=Fiedler|year=1999|title=Phraseology in planned languages|journal=Language Problems and Language Planning|publisher=John Benjamins Publishing Company|volume=23|issue=2|pages=175–187|doi=10.1075/lplp.23.2.05fie|issn=0272-2690|oclc=67125214}}</ref>

| |

| | familycolor =

| |

| |fam1=[[International auxiliary language]]

| |

| |creator=[[International Auxiliary Language Association]]

| |

| |created=1951

| |

| |setting=Scientific registration of international vocabulary; [[international auxiliary language]]

| |

| |posteriori='''Source languages''': [[English language|English]], [[French language|French]], [[Italian language|Italian]], [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]], and [[Spanish language|Spanish]], with reference to some other control languages (mainly [[German languages|German]] and [[Russian language|Russian]]).

| |

| |script=[[Latin script]]

| |

| |agency=No regulating body

| |

| |iso1=ia

| |

| |iso2=ina

| |

| |iso3=ina

| |

| |image=150px-Interlingua-Logo.png

| |

| |imagesize=150px

| |

| |imagecaption=Logo

| |

| |notice=IPA

| |

| |glotto=inte1239

| |

| |glottorefname=Interlingua (International Auxiliary Language Association)

| |

| }}

| |

|

| |

| '''Interlingua''' ({{IPAc-en|ɪ|n|t|ər|ˈ|l|ɪ|ŋ|ɡ|w|ə}}; [[ISO 639]] language codes ''ia'', ''ina'') is an [[Italic languages|Italic]] [[international auxiliary language]] (IAL), developed between 1937 and 1951 by the [[International Auxiliary Language Association]] (IALA). It ranks among the top most widely used IALs, and is the most widely used [[International auxiliary language#Classification|naturalistic]] IAL<ref name="gopsill1990">{{cite book|last=Gopsill|first=F. P.|title=International languages: a matter for Interlingua|year=1990|publisher=British Interlingua Society|location=[[Sheffield]], [[England]]|isbn=0-9511695-6-4|oclc=27813762}}</ref> – in other words, those IALs whose vocabulary, grammar and other characteristics are derived from natural languages, rather than being centrally planned. Interlingua was developed to combine a simple, mostly regular grammar<ref>See Gopsill, F. P. ''Interlingua: A course for beginners.'' Part 1. Sheffield, England: British Interlingua Society, 1987. Gopsill, here and elsewhere, characterizes Interlingua as having a simple grammar and no irregularities.</ref><ref>The [[Interlingua: A Grammar of the International Language|Interlingua Grammar]] suggests that Interlingua has a small number of irregularities. See Gode (1955).</ref> with a vocabulary common to the widest possible range of western European languages,<ref name="iala1971">{{cite book|last1=Gode|first1=Alexander|chapter=Introduction|url=http://www.bowks.net/worldlang/aux/b_IED.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071227051537/http://www.bowks.net/worldlang/aux/b_IED.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=2007-12-27|title=Interlingua-English: A dictionary of the international language|edition=Revised|location=New York|publisher=Continuum International Publishing Group|year=1971}}</ref> making it unusually easy to learn, at least for those whose native languages were sources of Interlingua's [[vocabulary]] and grammar.<ref name="breinstrup-beginners">Breinstrup, Thomas, Preface, [http://www.interlingua.com/archivos/Prefacio%20-%20Contento.pdf ''Interlingua course for beginners''], Bilthoven, Netherlands: Union Mundial pro Interlingua, 2006.</ref> Conversely, it is used as a rapid introduction to many natural languages.<ref name="gopsill1990"/>

| |

|

| |

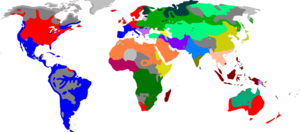

| Interlingua literature maintains that (written) Interlingua is comprehensible to the hundreds of millions of people who speak [[Romance languages]],<ref>{{cite book|last1=Yeager|first1=Leland B.|chapter=Le linguistica como reclamo pro Interlingua|trans-chapter=Linguistics as an advertisement for Interlingua|title=Interlinguistica e Interlingua: Discursos public|location=Beekbergen, Netherlands|publisher=Servicio de Libros UMI|year=1991}}</ref> though it is actively spoken by only a few hundred.<ref name="Fiedler"/>

| |

|

| |

| The name Interlingua comes from the Latin words ''{{wiktla|inter}}'', meaning "between", and ''{{wiktla|lingua}}'', meaning "tongue" or "language". These [[morpheme]]s are identical in Interlingua. Thus, "Interlingua" would mean "between language".

| |

|

| |

| == Rationale ==

| |

| {{Advert section|date=February 2021}}

| |

|

| |

| The expansive movements of science, technology, trade, diplomacy, and the arts, combined with the historical dominance of the [[Greek language|Greek]] and [[Latin language|Latin]] languages have resulted in a large common vocabulary among European languages. With Interlingua, an objective procedure is used to extract and standardize the most widespread word or words for a concept found in a set of '''primary control languages''': [[English language|English]], [[French language|French]], [[Italian language|Italian]], [[Spanish language|Spanish]] and [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]], with [[German language|German]] and [[Russian language|Russian]] as '''secondary control languages'''.<ref name="iala1971"/> Words from any language are eligible for inclusion, so long as their internationality is shown by their presence in these control languages. Hence, Interlingua includes such diverse word forms as [[Japanese language|Japanese]] ''geisha'' and ''samurai'', [[Arabic language|Arabic]] ''califa'', [[Guugu Yimithirr language|Guugu Yimithirr]] ''gangurru'' (Interlingua: kanguru), and [[Finnish language|Finnish]] ''sauna''.<ref name="iala1971"/>

| |

|

| |

| Interlingua combines this pre-existing vocabulary with a minimal grammar based on the control languages. People with a good knowledge of a Romance language, or a smattering of a Romance language plus a good knowledge of the ''[[international scientific vocabulary]]'' can frequently understand it immediately on reading or hearing it. The immediate comprehension of Interlingua, in turn, makes it unusually easy to learn. Speakers of [[language|other languages]] can also learn to speak and write Interlingua in a short time, thanks to its simple grammar and regular word formation using a small number of [[root (linguistics)|roots]] and [[affix]]es.<ref name="many-represented">[[Alice Vanderbilt Morris|Morris, Alice Vanderbilt]], ''[http://www.interlingua.fi/ialagr45.htm#manyrepresented General Report] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040702192153/http://www.interlingua.fi/ialagr45.htm |date=2004-07-02 }}'', New York: International Auxiliary Language Association, 1945.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| Once learned, Interlingua can be used to learn other related languages quickly and easily, and in some studies, even to understand them immediately. Research with [[Swedish language|Swedish]] students has shown that, after learning Interlingua, they can translate elementary texts from Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. In one 1974 study, an Interlingua class translated a Spanish text that students who had taken 150 hours of Spanish found too difficult to understand.<ref name="gopsill1990"/> Gopsill has suggested that Interlingua's freedom from irregularities allowed the students to grasp the mechanisms of romance languages quickly.<ref name="gopsill1990"/><ref name="many-represented"/>

| |

|

| |

| == History ==

| |

| {{Main|History of Interlingua}}

| |

|

| |

| <!--[[Image:Interlinguadeiala-tenue&latin.jpg|thumb|One of the many unofficial logo designs created for Interlingua, displaying the main logo with a "control language" flag montage below.{{Deletable image-caption|Monday, 30 August 2010|date=May 2012}}]]-->

| |

| The American heiress [[Alice Vanderbilt Morris]] (1874–1950) became interested in [[linguistics]] and the [[international auxiliary language]] movement in the early 1920s, and in 1924, Morris and her husband, [[Dave Hennen Morris]], established the non-profit International Auxiliary Language Association (IALA) in [[New York City]]. Their aim was to place the study of IALs on a more complex and scientific basis. Morris developed the research program of IALA in consultation with [[Edward Sapir]], [[William Edward Collinson]], and [[Otto Jespersen]].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Falk|first1=Julia S.|title=Words without grammar: Linguists and the international language movement in the United States|journal=Language and Communication|volume=15|issue=3|pages=241–259|publisher=Pergamon|year=1995|doi=10.1016/0271-5309(95)00010-N}}</ref>

| |

|

| |

| === International Auxiliary Language Association ===

| |

| The IALA became a major supporter of mainstream American linguistics. Numerous studies by Sapir, Collinson, and [[Morris Swadesh]] in the 1930s and 1940s, for example, were funded by IALA. Alice Morris edited several of these studies and provided much of IALA's financial support.<ref name="iala1971_foreword">{{ cite book|last1=Bray|first1=Mary Connell|orig-year=1951|year=1971|chapter=Foreword|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071006090121/http://www.bowks.net/worldlang/aux/b_IED-foreword.html|archive-date=October 6, 2007|url=http://www.bowks.net/worldlang/aux/b_IED-foreword.html|title=Interlingua-English: A dictionary of the international Language|edition=2nd|location=New York|publisher=Frederick Ungar Publishing Company|isbn=0-8044-0188-8|oclc=162319|access-date=April 18, 2010}}</ref> IALA also received support from such prestigious groups as the [[Carnegie Corporation]], the [[Ford Foundation]], the [[Research Corporation]], and the [[Rockefeller Foundation]].<ref name="gopsill-historia">Gopsill, F. P., and Sexton, Brian, [http://www.interlingua.com/historia/diverse/historia-1.htm "Le historia antenatal de interlingua"], ''Historia de interlingua'', 2001, revised 2006.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| In its early years, IALA concerned itself with three tasks: finding other organizations around the world with similar goals; building a library of books about [[language]]s and [[interlinguistics]]; and comparing extant IALs, including [[Esperanto]], [[Esperanto II]], [[Ido (language)|Ido]], [[Latino sine flexione|Peano's Interlingua]] (Latino sine flexione), [[Novial]], and [[Interlingue]] (Occidental). In pursuit of the last goal, it conducted parallel studies of these languages, with comparative studies of national languages, under the direction of scholars at American and European universities.<ref name="iala1971_foreword"/> It also arranged conferences with proponents of these IALs, who debated features and goals of their respective languages. With a "concession rule" that required participants to make a certain number of concessions, early debates at IALA sometimes grew from heated to explosive.<ref name="gopsill1990"/>{{clarify|date=July 2019}}

| |

|

| |

| At the Second International Interlanguage Congress, held in [[Geneva]] in 1931, IALA began to break new ground; 27 recognized linguists signed a testimonial of support for IALA's research program. An additional eight added their signatures at the third congress, convened in [[Rome]] in 1933.<ref name="gopsill1990"/> That same year, [[Herbert N. Shenton]] and [[Edward L. Thorndike]] became influential in IALA's work by authoring key studies in the interlinguistic field.<ref name="iala1971_foreword"/>

| |

|

| |

| The first steps towards the finalization of Interlingua were taken in 1937, when a committee of 24 eminent linguists from 19 universities published ''Some Criteria for an International Language and Commentary''. However, the outbreak of [[World War II]] in 1939 cut short the intended biannual meetings of the committee.<ref name="gopsill1990"/>

| |

|

| |

| ===Development of a new language===

| |

| Originally, the association had not intended to create its own language. Its goal was to identify which auxiliary language already available was best suited for international communication, and how to promote it more effectively. However, after ten years of research, many more members of IALA concluded that none of the existing [[interlanguage]]s were up to the task. By 1937, the members had made the decision to create a new language, to the surprise of the world's interlanguage community.<ref name="gopsill-historia2">Gopsill, F. P., and Sexton, Brian, [http://www.interlingua.com/historia/diverse/historia-2.htm "Profunde recerca duce a un lingua"], ''Historia de interlingua'', 2001, revised 2006.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| To that point, much of the debate had been equivocal on the decision to use naturalistic (e.g., [[Latino sine flexione|Peano's Interlingua]], [[Novial]] and [[Interlingue|Occidental]]) or systematic (e.g., [[Esperanto]] and [[Ido (language)|Ido]]) words. During the war years, proponents of a naturalistic interlanguage won out. The first support was Thorndike's paper; the second was a concession by proponents of the systematic languages that thousands of words were already present in many, or even a majority, of the European languages. Their argument was that systematic derivation of words was a [[Procrustes|Procrustean bed]], forcing the learner to unlearn and re-memorize a new derivation scheme when a usable vocabulary was already available. This finally convinced supporters of the systematic languages, and IALA from that point assumed the position that a naturalistic language would be best.<ref name="gopsill1990"/>

| |

|

| |

| IALA's research activities were based in [[Liverpool]], before relocating to [[New York City|New York]] due to the outbreak of [[World War II]], where [[Ezra Clark Stillman|E. Clark Stillman]] established a new research staff.<ref name="iala1971_foreword"/> Stillman, with the assistance of [[Alexander Gode]], developed a ''prototyping'' technique – an objective methodology for selecting and standardizing vocabulary based on a comparison of ''control languages''.<ref name="gopsill1990"/>

| |

|

| |

| In 1943 Stillman left for war work and Gode became Acting Director of Research.<ref name="iala1971_foreword"/> IALA began to develop models of the proposed language, the first of which were presented in Morris's ''General Report'' in 1945.<ref name="gopsill-historia2"/>

| |

|

| |

| From 1946 to 1948, French linguist [[André Martinet]] was Director of Research. During this period IALA continued to develop models and conducted polling to determine the optimal form of the final language. In 1946, IALA sent an extensive survey to more than 3,000 language teachers and related professionals on three continents.<ref name="gopsill1990"/><ref name="gopsill-historia3">Gopsill, F. P., and Sexton, Brian, [http://www.interlingua.com/historia/diverse/historia-3.htm "Le natura, si – un schema, no"], ''Historia de interlingua'', 2001, revised 2006.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| Four models were canvassed:<ref name="gopsill1990"/>

| |

|

| |

| {| border=0

| |

| |- valign=top

| |

| | || Model P || || highly naturalistic, with word forms unchanged from the prototypes

| |

| |- valign=top

| |

| | || Model M || || moderately naturalistic, similar to Occidental

| |

| |- valign=top

| |

| | || Model C || || slightly schematic, along the lines of Novial

| |

| |- valign=top

| |

| | || Model K || || moderately schematic, similar to Ido (less schematic than Esperanto)

| |

| |}

| |

|

| |

| The results of the survey were striking. The two more schematic models were rejected – K overwhelmingly. Of the two naturalistic models, M received somewhat more support than P. IALA decided on a compromise between P and M, with certain elements of C.<ref name="gopsill-historia3"/>

| |

|

| |

| Martinet took up a position at [[Columbia University]] in 1948, and Gode took on the last phase of Interlingua's development.<ref name="iala1971_foreword"/> The vocabulary and grammar of Interlingua were first presented in 1951, when IALA published the finalized ''[[Interlingua: A Grammar of the International Language|Interlingua Grammar]]'' and the 27,000-word ''[[Interlingua-English Dictionary|Interlingua–English Dictionary]]'' (IED). In 1954, IALA published an introductory manual entitled ''[[Interlingua a Prime Vista]]'' ("Interlingua at First Sight").

| |

|

| |

| Interlingua as presented by the IALA is very close to [[Latino sine flexione|Peano's Interlingua]] (Latino sine flexione), both in its grammar and especially in its vocabulary. Accordingly, the very name "Interlingua" was kept, yet a distinct abbreviation was adopted: IA instead of IL.

| |

|

| |

| ===Success, decline, and resurgence===

| |

| An early practical application of Interlingua was the scientific newsletter ''Spectroscopia Molecular'', published from 1952 to 1980.<ref>Breinstrup, Thomas, [http://www.interlingua.com/historia/publicationes/spectroscopia.htm "Un revolution in le mundo scientific" (A revolution in the scientific world).] Accessed January 16, 2007.</ref> In 1954, Interlingua was used at the Second World Cardiological Congress in [[Washington, D.C.]] for both written summaries and oral interpretation. Within a few years, it found similar use at nine further medical congresses. Between the mid-1950s and the late 1970s, some thirty scientific and especially medical journals provided article summaries in Interlingua. [[Society for Science and the Public|Science Service]], the publisher of ''Science Newsletter'' at the time, published a monthly column in Interlingua from the early 1950s until Gode's death in 1970. In 1967, the [[International Organization for Standardization]], which normalizes terminology, voted almost unanimously to adopt Interlingua as the basis for its dictionaries.<ref name="gopsill1990"/>

| |

|

| |

| The [[International Auxiliary Language Association|IALA]] closed its doors in 1953 but was not formally dissolved until 1956 or later.<ref name = "esterhill2000"/> Its role in promoting Interlingua was largely taken on by Science Service,<ref name="gopsill-historia3"/> which hired Gode as head of its newly formed [[Interlingua Division of Science Service|Interlingua Division]].<ref>[http://www.interlingua.com/historia/biographias/gode.htm Biographias: Alexander Gottfried Friedrich Gode-von Aesch]. Accessed January 16, 2007</ref> [[Hugh E. Blair]], Gode's close friend and colleague, became his assistant.<ref>[http://www.interlingua.com/historia/biographias/blair.htm Biographias: Hugh Edward Blair.] Accessed January 16, 2007</ref> A successor organization, the Interlingua Institute,<ref name="portrait-organizations">[http://www.interlingua.com/historia/diverse/organisationes.htm Portrait del organisationes de interlingua.] Access January 16, 2007.</ref> was founded in 1970 to promote Interlingua in the US and Canada. The new institute supported the work of other linguistic organizations, made considerable scholarly contributions and produced Interlingua summaries for scholarly and medical publications. One of its largest achievements was two immense volumes on phytopathology produced by the American Phytopathological Society in 1976 and 1977.<ref name="esterhill2000">Esterhill, Frank, ''Interlingua Institute: A History''. New York: Interlingua Institute, 2000.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| Interlingua had attracted many former adherents of other international-language projects, notably [[Interlingue|Occidental]] and Ido. The former Occidentalist [[Ric Berger]] founded The [[Union Mundial pro Interlingua]] ([[Union Mundial pro Interlingua|UMI]]) in 1955,<ref name="portrait-organizations"/> and by the late 1950s, interest in Interlingua in Europe had already begun to overtake that in North America.

| |

|

| |

| Beginning in the 1980s, UMI has held international conferences every two years (typical attendance at the earlier meetings was 50 to 100) and launched a publishing programme that eventually produced over 100 volumes. Other Interlingua-language works were published by university presses in [[Sweden]] and [[Italy]], and in the 1990s, [[Brazil]] and [[Switzerland]].<ref>[http://www.interlingua.com/libros/pt.htm Bibliographia de Interlingua.] Accessed January 16, 2007.</ref><ref>[http://www.interlingua.com/historia/biographias/stenstrom.htm Biographias: Ingvar Stenström.] Accessed January 16, 2007</ref> Several [[Scandinavia]]n schools undertook projects that used Interlingua as a means of teaching the international scientific and intellectual vocabulary.<ref name = "breinstrup-futur"/>

| |

|

| |

| In 2000, the Interlingua Institute was dissolved amid funding disputes with the UMI; the American Interlingua Society, established the following year, succeeded the institute and responded to new interest emerging in [[Mexico]].<ref name="portrait-organizations"/>

| |

|

| |

| ===In the Soviet bloc===

| |

| Interlingua was spoken and promoted in the [[Soviet bloc]], despite attempts to suppress the language. In [[East Germany]], government officials confiscated the letters and magazines that the UMI sent to Walter Rädler, the Interlingua representative there.<ref>"Interlingua usate in le posta". [http://www.interlingua.com/historia/diverse/stampaspostal.htm Historia de Interlingua], 2001, revised 2006.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| In [[Czechoslovakia]], [[Július Tomin (Interlingua)|Július Tomin]] published his first article on Interlingua in the Slovak magazine ''Príroda a spoločnosť'' (Nature and Society) in 1971, after which he received several anonymous threatening letters.<ref>{{cite magazine|last1=Breinstrup|first1=Thomas|title=Persecutate pro parlar Interlingua|magazine=[[Panorama in Interlingua]]|year=1995|issue=5}}</ref> He went on to become the Czech Interlingua representative, teach Interlingua in the school system, and publish a series of articles and books.<ref>[http://www.interlingua.com/historia/biographias/tomin.htm Biographias: Július Tomin. Historia de Interlingua, 2001.] Revised 2006.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| ===Interlingua today===

| |

| {{See also|#Community}}

| |

|

| |

| Today,{{when|date=September 2019}} interest in Interlingua has expanded from the scientific community to the general public. Individuals, governments, and private companies use Interlingua for learning and instruction, travel, online publishing, and communication across language barriers.<ref name = "breinstrup-futur"/><ref>Breinstrup, Thomas, [http://www.interlingua.com/historia/diverse/tourismo.htm "Contactos directe con touristas e le gente local"], Historia de Interlingua, 2001, Revised 2006.</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Stenström|first1=Ingvar|title=Experientias del inseniamento del vocabulario international in le nove gymnasio svedese|trans-title=Experiences with the teaching of the international vocabulary in the new Swedish gymnasium|journal=Interlinguistica e Interlingua: Discursos public per Ingvar Stenström e Leland B. Yeager|location=Beekbergen, Netherlands|publisher=Servicio de Libros UMI|year=1991}} (High school in Europe is often called the gymnasium.)</ref> Interlingua is promoted internationally by the [[Union Mundial pro Interlingua]]. Periodicals and books are produced by many national organizations, such as the Societate American pro Interlingua, the [[Swedish Society for Interlingua|Svenska Sällskapet för Interlingua]], and the [[Union Brazilian pro Interlingua]].<ref name="portrait-organizations"/>

| |

|

| |

| == Community ==

| |

| It is not certain how many people have an active knowledge of Interlingua. As noted above, Interlingua is claimed to be the most widely spoken naturalistic [[International auxiliary language|auxiliary language]].<ref name="gopsill1990"/>

| |

|

| |

| Interlingua's greatest advantage is that it is the most widely ''understood'' [[international auxiliary language]] besides [[Latino sine flexione|Interlingua (IL) de A.p.I.]]{{citation needed|date=December 2020}} by virtue of its naturalistic (as opposed to schematic) grammar and vocabulary, allowing those familiar with a Romance language, and educated speakers of English, to read and understand it without prior study.<ref name="blandino1989">Blandino, Giovanni, "Le problema del linguas international auxiliari", ''Philosophia del Cognoscentia e del Scientia'', Rome, Italy: Pontificia Universitas Lateranensis, Pontificia Universitas Urbaniana, 1989.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| Interlingua has active speakers on all continents, especially in [[South America]] and in [[Eastern Europe|Eastern]] and [[Northern Europe]], most notably [[Scandinavia]]; also in [[Russia]] and [[Ukraine]]. There are copious Interlingua web pages,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://arocholaw.com/welcome/benvenite|title=AROCHO LAW OFFICE - Benvenite-Washington DC Advocato-servir organisationes sinscopo lucrative & interprisas US Virgin Islands - Interlingua|work=arocholaw.com|access-date=23 June 2016}}</ref> including editions of [[Interlingua Wikipedia|Wikipedia]] and [http://ia.wiktionary.org Wiktionary], and a number of periodicals, including ''Panorama in Interlingua'' from the [[Union Mundial pro Interlingua]] (UMI) and magazines of the national societies allied with it. There are several active mailing lists, and Interlingua is also in use in certain [[Usenet]] newsgroups, particularly in the europa.* hierarchy. Interlingua is presented on CDs, radio, and television.<ref>"Radioemissiones in e re Interlingua," ''[[Panorama in Interlingua]]'', Issue 3, 2006.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| Interlingua is taught in many high schools and universities, sometimes as a means of teaching other languages quickly, presenting [[interlinguistics]], or introducing the international vocabulary.<ref name="breinstrup-futur">Breinstrup, Thomas, [http://www.interlingua.com/historia/diverse/50annos.htm "Interlingua: Forte, Fructuose, Futur"], Historia de Interlingua, 2001, Revised 2006.</ref><ref name="stenström-communication">Stenström, Ingvar, “The Interlingua of IALA: From ‘the linguists’ project’ of 1951 to the working ‘tool of international scientific communication’ of 1981”, ''Interlinguistica e Interlingua: Discursos public per Ingvar Stenström e Leland B. Yeager'', Beekbergen, Netherlands: Servicio de Libros UMI, 1991.</ref><ref name="stenström-utilisation">Stenström, Ingvar, “Utilisation de Interlingua in le inseniamento de linguas” (Utilization of Interlingua in the teaching of languages), ''Interlinguistica e Interlingua: Discursos public per Ingvar Stenström e Leland B. Yeager'', Beekbergen, Netherlands: Servicio de Libros UMI, 1991.</ref> The [[University of Granada]] in [[Spain]], for example, offers an Interlingua course in collaboration with the Centro de Formación Continua.<ref>"A notar," ''[[Panorama in Interlingua]],'' Issue 4, 2006.</ref>

| |

|

| |

| Every two years, the UMI organizes an international conference in a different country. In the year between, the Scandinavian Interlingua societies co-organize a conference in Sweden. National organizations such as the Union Brazilian pro Interlingua also organize regular conferences.<ref name="breinstrup-futur"/>

| |

|

| |

| {{Asof|2019}}, [[Google Keyboard]] supports Interlingua.

| |

|

| |

| == Orthography ==

| |

| Interlingua has a largely [[phonemic orthography]].

| |

|

| |

| === Interlingua alphabet ===

| |

| Interlingua uses the 26 letters of the [[ISO basic Latin alphabet]] with no [[diacritic]]s.<ref>[http://www.omniglot.com/writing/interlingua.htm Interlingua Alphabet] on Omniglot</ref> The alphabet, pronunciation in [[International Phonetic Alphabet|IPA]] and letter names in Interlingua are:

| |

|

| |

| {| class="wikitable"

| |

| |+ Interlingua alphabet

| |

| ! Number ||1||2||3||4||5||6||7||8||9||10||11||12||13||14||15||16||17||18||19||20||21||22||23||24||25||26

| |

| |-

| |

| |''Letters ([[upper case]])''|| A || B || C || D || E || F || G || H || I || J || K || L || M || N || O || P || Q || R || S || T || U || V || W || X || Y || Z

| |

| |-

| |

| |''Letters ([[lower case]])''|| a || b || c || d || e || f || g || h || i || j || k || l || m || n || o || p || q || r || s || t || u || v || w || x || y || z

| |

| |-

| |

| |''[[International Phonetic Alphabet|IPA]]''|| {{IPAblink|a}} || {{IPAblink|b}} || {{IPAblink|k}}, {{IPAblink|t͡s}} ~ {{IPAblink|t͡ʃ}}<sup>1</sup> || {{IPAblink|d}} || {{IPAblink|e}} || {{IPAblink|f}} || {{IPAblink|ɡ}} <sup>4</sup> || {{IPAblink|h}} ~ {{IPAblink|∅}} || {{IPAblink|i}} || {{IPAblink|ʒ}} || {{IPAblink|k}} || {{IPAblink|l}} || {{IPAblink|m}} || {{IPAblink|n}} || {{IPAblink|o}} || {{IPAblink|p}} || {{IPAblink|k}} <sup>2</sup> || {{IPAblink|r}} || {{IPAblink|s}} ~ {{IPAblink|z}} <sup>3</sup> || {{IPAblink|t}} <sup>4</sup> || {{IPAblink|u}} || {{IPAblink|v}} || {{IPAblink|w}} ~ {{IPAblink|v}} || {{IPA|[ks]}} || {{IPAblink|i}} || {{IPAblink|z}}

| |

| |-

| |

| |''Names''|| a || be || ce || de || e || ef || ge || ha || i || jota || ka || el || em || en || o || pe || cu || er || es || te || u || ve || duple ve || ix || ypsilon || zeta

| |

| |}

| |

|

| |

|

| # ''c'' is pronounced {{IPAblink|t͡s}} (or optionally {{IPAblink|s}}) before ''e, i, y''

| | == Anthropology == |

| ## ''ch'' is pronounced /ʃ/ in words of French origin e.g. ''chef'' = /ʃef/ meaning "chief" or "chef", /k/ in words of Greek and Italian origin e.g. ''choro'' = /koro/ meaning "chorus" and more rarely /t͡ʃ/ in words of English or Spanish origin as in ''Chile'' /t͡ʃile/ (the country [[Chile]]). Ch may be pronounced either /t͡ʃ/ or /ʃ/ depending on the speaker in many cases e.g. ''chocolate'' may be pronounced either /t͡ʃokolate/ or /ʃokolate/.

| | Interlingua (/ɪnterˈlɪŋɡwə/; ISO 639 language codes ia, ina) is an Italic international auxiliary language (IAL), developed between 1937 and 1951 by the International Auxiliary Language Association (IALA) . It ranks among the top most widely used IALs (along with Esperanto and Ido), and is the most widely used naturalistic IAL: in other words, its vocabulary, grammar and other characteristics are derived from natural languages, rather than being centrally planned. Interlingua was developed to combine a simple, mostly regular grammar with a vocabulary common to the widest possible range of western European languages, making it unusually easy to learn, at least for those whose native languages were sources of Interlingua's vocabulary and grammar. Conversely, it is used as a rapid introduction to many natural languages. |

| ## there is no consensus on how to pronounce ''sc'' before ''e, i, y'', as in ''scientia'' "science", though {{IPA|[st͡s]}} is common

| |

| # ''q'' only appears in the digraph ''qu'', which is pronounced {{IPA|[kw]}} (but {{IPAblink|k}} in the conjunction and pronoun ''que'' and pronoun ''qui'' and in terms derived from them such as ''anque'' and ''proque'')

| |

| # a single ''s'' between vowels is often pronounced like ''z'', but pronunciation is irregular

| |

| # ''t'' is generally {{IPA|[t]}}, but ''ti'' followed by a vowel, unless stressed or preceded by ''s'', is pronounced the same as ''c'' (that is, {{IPA|[t͡sj]}} or {{IPA|[sj]}})

| |

| # Unlike any of the Romance languages, ''g'' is /g/ even before ''e, i, y''

| |

| ## but in ''-age'' it is /(d)ʒ/ (i.e. like ''j''), as it is in several words of French origin such as ''orange'' /oranʒe/ and ''mangiar'' /manʒar/

| |

|

| |

|

| ===Collateral orthography===

| | The name Interlingua comes from the Latin words inter, meaning "between", and lingua, meaning "tongue" or "language". These morphemes are identical in Interlingua. |

| {{expand section|date=September 2019}}

| |

| The book ''Grammar of Interlingua'' defines in §15 a "collateral orthography".<ref>{{cite web|url=https://adoneilson.com/int/gi/spell/collat.html|title=''Grammar of Interlingua''}}</ref> | |

|

| |

|

| == Phonology == | | == Phonology == |

| | | {{Main|Interlingua/Phonology}} |

| [[File:Vocabulario scientific international.ogg|thumb|Spoken Interlingua]]

| | === Consonants=== |

| | | {| class="wikitable" style="width:auto;" |

| Interlingua is primarily a written language, and the pronunciation is not entirely settled. The sounds in parentheses are not used by all speakers.

| |

| | |

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" | |

| |- | | |- |

| ! | | ! |

| ! colspan="2" | [[Labial consonant|Labial]] | | ! colspan="2" | Bilabial |

| ! colspan="2" | [[Alveolar consonant|Alveolar]] | | ! colspan="2" | Labio-<br />dental |

| ! colspan="2" | [[Postalveolar consonant|Post-<br>alveolar]] | | ! colspan="2" | Alveolar |

| ! [[Palatal consonant|Palatal]] | | ! colspan="2" | Post-<br />alveolar |

| ! colspan="2" | [[Velar consonant|Velar]] | | ! Palatal |

| ! [[Glottal consonant|Glottal]] | | ! Labial-<br />velar |

| | ! colspan="2" | Velar |

| | ! Glottal |

| |- | | |- |

| ! [[Nasal stop|Nasal]] | | ! Plosive |

| | colspan="2"| {{IPA|m}} | | | {{IPA|p}} || {{IPA|b}} |

| | colspan="2" | {{IPA|n}} | | | colspan="2"| |

| | | {{IPA|t}} || {{IPA|d}} |

| | colspan="2"| | | | colspan="2"| |

| | | | | |

| | colspan="2"| | | | |

| | | {{IPA|k}} || {{IPA|ɡ}} |

| | | | | |

| |- | | |- |

| ! [[Plosive consonant|Plosive]] | | ! Nasal |

| | {{IPA|p}} || {{IPA|b}} | | | || {{IPA|m}} |

| | {{IPA|t}} || {{IPA|d}} | | | colspan="2"| |

| | | || {{IPA|n}} |

| | colspan="2"| | | | colspan="2"| |

| | | | | |

| | {{IPA|k}} || {{IPA|ɡ}} | | | |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | | | | |

| |- | | |- |

| ! [[Affricate consonant|Affricate]] | | ! Tap |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | | || {{IPA|ɾ}} |

| | colspan="2"| | | | colspan="2"| |

| | colspan="3"| ({{IPA|ts ~ tʃ}}) | | | |

| | rowspan=2| {{IPA|(d)ʒ}}

| |

| | | | | |

| | colspan="2"| | | | colspan="2"| |

| | | | | |

| |- | | |- |

| ! [[Fricative consonant|Fricative]] | | ! Fricative |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | {{IPA|f}} || {{IPA|v}} | | | {{IPA|f}} || {{IPA|v}} |

| | {{IPA|s}} || {{IPA|z}} | | | {{IPA|s}} || {{IPA|z}} |

| | {{IPA|ʃ}} ||| | | | {{IPA|ʃ}} || rowspan=2| {{IPA|(d)ʒ}} |

| | colspan="2"| | | | |

| | | |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | ({{IPA|h}}) | | | ({{IPA|h}}) |

| |- | | |- |

| ! [[Approximant consonant|Approximant]] | | ! Affricates |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | | colspan="3"| ({{IPA|ts ~ tʃ}}) |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | | |

| | |- |

| | ! Approximant |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | colspan="2"| | | | colspan="2"| |

| | colspan="2"|{{IPA|l}}

| |

| | colspan="2"| | | | colspan="2"| |

| | {{IPA|j}} | | | {{IPA|j}} |

| | colspan="2" |{{IPA|w}}

| | | {{IPA|w}} |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | | | | |

| |- | | |- |

| ! [[Rhotic consonant|Rhotic]] | | ! Lateral approximant |

| | | colspan="2"| |

| | colspan="2"| | | | colspan="2"| |

| | colspan="2" |{{IPA|ɾ}} | | | || {{IPA|l}} |

| | colspan="2"| | | | colspan="2"| |

| | | |

| | | | | |

| | colspan="2"| | | | colspan="2"| |

| Line 223: |

Line 106: |

| |} | | |} |

|

| |

|

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" | | === Vowels === |

| | {| class="wikitable" style="width:auto;" |

| |- | | |- |

| ! | | ! |

| ! [[Front vowel|Front]] | | ! Front |

| ! [[Back vowel|Back]] | | ! Back |

| |- | | |- |

| ! [[Close vowel|Close]] | | ! High |

| | {{IPA|i}} | | | {{IPA|i}} |

| | {{IPA|u}} | | | {{IPA|u}} |

| |- | | |- |

| ! [[Close-mid vowel|Close-mid]] | | ! High-mid |

| | {{IPA|e}} | | | {{IPA|e}} |

| | {{IPA|o}} | | | {{IPA|o}} |

| |- | | |- style="text-align:center" |

| ! [[Open vowel|Open]] | | ! Low |

| | colspan=2|{{IPA|a}} | | | colspan=2|{{IPA|a}} |

| |} | | |} |

|

| |

|

| ===Pronunciation=== | | == Orthography == |

| For the most part, [[consonant]]s are pronounced as in English, while the [[vowel]]s are like Spanish. Written double consonants may be [[geminated]] as in Italian for extra clarity or pronounced as single as in English or French. Interlingua has five falling [[diphthong]]s, {{IPA|/ai/, /au/, /ei/, /eu/}}, and {{IPA|/oi/}},<ref>Gopsill, F. P., ''Interlingua today: A course for beginners'', Sheffield, UK: British Interlingua Society, 1994.</ref> although {{IPA|/ei/}} and {{IPA|/oi/}} are rare.

| |

|

| |

|

| === Stress === | | {| class="wikitable" |

| The ''general rule'' is that stress falls on the vowel before the last consonant (e.g., ''l'''i'''ngua'', 'language', ''ess'''e'''r'', 'to be', ''requirim'''e'''nto'', 'requirement') ignoring the final plural ''-(e)s'' (e.g. ''l'''i'''nguas'', the plural of ''lingua'', still has the same stress as the singular), and where that is not possible, on the first vowel (''v'''i'''a'', 'way', '''''i'''o cr'''e'''a'', 'I create'). There are a few exceptions, and the following rules account for most of them:

| | |''Letters (upper case)''|| A || B || C || D || E || F || G || H || I || J || K || L || M || N || O || P || Q || R || S || T || U || V || W || X || Y || Z |

| * Adjectives and nouns ending in a vowel followed by ''-le, -ne,'' or ''-re'' are stressed on the third-last syllable (''fr'''a'''gile, m'''a'''rgine, '''a'''ltere'' 'other', but ''illa imp'''o'''ne'' 'she imposes').

| | |- |

| * Words ending in ''-ica/-ico, -ide/-ido'' and ''-ula/-ulo,'' are stressed on the third-last syllable (''pol'''i'''tica, scient'''i'''fico, r'''a'''pide, st'''u'''pido, cap'''i'''tula, s'''e'''culo'' 'century').

| | |''Letters (lower case)''|| a || b || c || d || e || f || g || h || i || j || k || l || m || n || o || p || q || r || s || t || u || v || w || x || y || z |

| * Words ending in ''-ic'' are stressed on the second-last syllable (''c'''u'''bic'').

| |

| | |

| Speakers may pronounce all words according to the general rule mentioned above. For example, ''kilom'''e'''tro'' is acceptable, although ''kil'''o'''metro'' is more common.<ref name="gode1955">{{cite book|last=Gode|first=Alexander|author-link=Alexander Gode|author2=Hugh E. Blair|author2-link=Hugh E. Blair|title=Interlingua; a grammar of the international language|url=https://archive.org/details/interlinguagramm00gode|access-date=2007-03-05|edition=Second|orig-year=1951|year=1955|publisher=Frederick Ungar Publishing|location=[[New York City|New York]]|isbn=0-8044-0186-1|oclc=147452}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| === Phonotactics ===

| |

| Interlingua has no explicitly defined [[phonotactics]]. However, the prototyping procedure for determining Interlingua words, which strives for internationality, should in general lead naturally to words that are easy for most learners to pronounce. In the process of forming new words, an ending cannot always be added without a modification of some kind in between. A good example is the plural ''-s'', which is always preceded by a vowel to prevent the occurrence of a hard-to-pronounce consonant cluster at the end. If the singular does not end in a vowel, the final ''-s'' becomes ''-es.''{{Citation needed|date=January 2010}}

| |

| | |

| === Loanwords ===

| |

| Unassimilated foreign [[loanword]]s, or borrowed words, are spelled as in their language of origin. Their spelling may contain [[diacritic]]s, or accent marks. If the diacritics do not affect pronunciation, they are removed.<ref name="iala1971"/>

| |

| | |

| == Vocabulary ==

| |

| {{See also|Free word-building in Interlingua}}

| |

| | |

| Words in Interlingua may be taken from any language,<ref>Morris, Alice Vanderbilt, [http://www.interlingua.fi/ialagr45.htm#factsreasoning "IALA's system: Underlying facts and reasoning"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040702192153/http://www.interlingua.fi/ialagr45.htm |date=2004-07-02 }}, ''General report'', New York: International Auxiliary Language Association, 1945.</ref> as long as their internationality is verified by their presence in seven ''control'' languages: [[Spanish language|Spanish]], [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]], [[Italian language|Italian]], [[French language|French]], and [[English language|English]], with [[German language|German]] and [[Russian language|Russian]] acting as secondary controls. These are the most widely spoken [[Romance language|Romance]], [[Germanic language|Germanic]], and [[Slavic language]]s, respectively. Because of their close relationship, Spanish and Portuguese are treated as one unit. The largest number of Interlingua words are of [[Latin language|Latin]] origin, with the [[Greek language|Greek]] and [[Germanic language|Germanic]] languages providing the second and third largest number. The remainder of the vocabulary originates in [[Slavic languages|Slavic]] and non-[[Indo-European languages]].<ref name="iala1971"/>

| |

| | |

| === Eligibility ===

| |

| | |

| A word, that is a form with meaning, is eligible for the Interlingua vocabulary if it is verified by at least three of the four primary control languages. Either secondary control language can substitute for a primary language. Any word of Indo-European origin found in a control language can contribute to the eligibility of an international word.<ref name="interlinguistic-standardization">Stillman, E. Clark, and Gode, Alexander, ''Interlinguistic standardization'', New York: International Auxiliary Language Association, 1943. [http://www.interlingua.com/historia/publicationes/standardisation.htm Articles 82–100] translated by [[Stanley A. Mulaik]]. Revised 2006.</ref> In some cases, the archaic or ''potential'' presence of a word can contribute to its eligibility.

| |

| | |

| A word can be potentially present in a language when a [[Morphological derivation|derivative]] is present, but the word itself is not. English ''proximity'', for example, gives support to Interlingua ''proxime'', meaning 'near, close'. This counts as long as one or more control languages actually have this basic root word, which the Romance languages all do. Potentiality also occurs when a concept is represented as a [[compound (linguistics)|compound]] or derivative in a control language, the [[morpheme]]s that make it up are themselves international, and the combination adequately conveys the meaning of the larger word. An example is Italian ''fiammifero'' (lit. flamebearer), meaning "match, lucifer", which leads to Interlingua ''flammifero'', or "match". This word is thus said to be potentially present in the other languages although they may represent the meaning with a single morpheme.<ref name="iala1971"/>

| |

| | |

| Words do not enter the Interlingua vocabulary solely because [[cognate]]s exist in a sufficient number of languages. If [[semantic change|their meanings have become different over time]], they are considered different words for the purpose of Interlingua eligibility. If they still have one or more meanings in common, however, the word can enter Interlingua with this smaller set of meanings.<ref name="interlinguistic-standardization"/>

| |

| | |

| If this procedure did not produce an international word, the word for a concept was originally taken from Latin (see below). This only occurred with a few [[grammatical particle]]s.

| |

| | |

| === Form ===

| |

| The form of an Interlingua word is considered an ''international prototype'' with respect to the other words. On the one hand, it should be neutral, free from characteristics peculiar to one language. On the other hand, it should maximally capture the characteristics common to all contributing languages. As a result, it can be transformed into any of the contributing variants using only these language-specific characteristics. If the word has any derivatives that occur in the source languages with appropriate parallel meanings, then their [[morphology (linguistics)|morphological]] connection must remain intact; for example, the Interlingua word for 'time' is spelled ''tempore'' and not ''*tempus'' or ''*tempo'' in order to match it with its derived adjectives, such as ''temporal''.<ref>Gode, Alexander, "Introduction", ''Interlingua-English: A dictionary of the international language'', Revised Edition, New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 1971. See [https://web.archive.org/web/20071227020831/http://www.bowks.net/worldlang/aux/b_IED-intro2.html#series "Forms of international words in derivational series"].</ref>

| |

| | |

| The language-specific characteristics are closely related to the [[sound law]]s of the individual languages; the resulting words are often close or even identical to the most recent form common to the contributing words. This sometimes corresponds with that of [[Vulgar Latin]]. At other times, it is much more recent or even contemporary. It is never older than the classical period.<ref name="interlinguistic-standardization"/>

| |

| | |

| === An illustration ===

| |

| The French ''œil'', Italian ''occhio'', Spanish ''ojo'', and Portuguese ''olho'' appear quite different, but they descend from a historical form ''oculus''. German ''Auge'', Dutch ''oog'' and English ''eye'' (cf. Czech and Polish ''oko'', Ukrainian ''око'' ''(óko)'') are related to this form in that all three descend from [[Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European]] ''*okʷ''. In addition, international derivatives like ''ocular'' and ''oculista'' occur in all of Interlingua's control languages.<ref name="blandino1989"/> Each of these forms contributes to the eligibility of the Interlingua word.<ref name="interlinguistic-standardization"/> German and English base words do not influence the form of the Interlingua word, because their Indo-European connection is considered too remote.<ref>Gode, Alexander, "Introduction", ''Interlingua-English: A dictionary of the international language'', Revised Edition, New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 1971. See [https://web.archive.org/web/20071227020831/http://www.bowks.net/worldlang/aux/b_IED-intro2.html#method "Methods and techniques: Non-Latin examples"].</ref> Instead, the remaining base words and especially the derivatives determine the form ''oculo'' found in Interlingua.<ref name="blandino1989"/>

| |

| | |

| == Grammar ==

| |

| {{Main|Interlingua grammar}}

| |

| | |

| Interlingua has been developed to omit any grammatical feature that is absent from any one primary control language. Thus, Interlingua has no [[agreement (linguistics)|noun–adjective agreement]] by gender, case, or number (cf. Spanish and Portuguese ''gatas negras'' or Italian ''gatte nere'', 'black female cats'), because this is absent from English, and it has no progressive verb tenses (English ''I am reading''), because they are absent from French. Conversely, Interlingua [[grammatical number|distinguishes singular nouns from plural nouns]] because all the control languages do.<ref name="gode1955"/> With respect to the secondary control languages, Interlingua has articles, unlike Russian.

| |

| | |

| The definite article ''le'' is invariable, as in English. Nouns have no [[grammatical gender]].<ref name="gode1955"/><ref name="wilgenhof1995">Wilgenhof, Karel. ''Grammatica de Interlingua''. Union Mundial pro Interlingua, Beekbergen, Netherlands, 1995.</ref> Plurals are formed by adding ''-s'', or ''-es'' after a final consonant.<ref name="gode1955"/> [[Personal pronouns]] take one form for the subject and one for the direct object and reflexive. In the third person, the reflexive is always ''se''.<ref name="gode1955"/><ref name="wilgenhof1995"/> Most [[adverb]]s are derived regularly from [[adjective]]s by adding ''-mente'', or ''-amente'' after a ''-c''. An adverb can be formed from any adjective in this way.<ref>Brauers, Karl. ''Grammatica synoptic de Interlingua''. Morges, Switzerland: Editiones Interlingua, 1975.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Verbs take the same form for all persons (''io vive, tu vive, illa vive'', 'I live', 'you live', 'she lives'). The [[indicative]] (''pare'', 'appear', 'appears') is the same as the [[Imperative mood|imperative]] (''pare!'' 'appear!'), and there is no [[subjunctive]].<ref name="gode1955"/> Three common verbs usually take short forms in the present tense: ''es'' for 'is', 'am', 'are;' ''ha'' for 'has', 'have;' and ''va'' for 'go', 'goes'.<ref name="wilgenhof1995"/> A few irregular verb forms are available, but rarely used.<ref>These are optional short forms for ''esser'', 'to be'. They are found in Wilgenhof, who stops short of calling them irregular verb forms. Two such forms appear in Gode and Blair, and one is labeled irregular; none are in Brauers.</ref>

| |

| | |

| There are four simple tenses (present, past, future, and conditional), three compound tenses (past, future, and conditional), and the passive voice. The compound structures employ an auxiliary plus the infinitive or the past participle (e.g., ''Ille ha arrivate'', 'He has arrived').<ref name="gode1955"/> Simple and compound tenses can be combined in various ways to express more complex tenses (e.g., ''Nos haberea morite'', 'We would have died').<ref>See for example Gode (1955), [http://members.optus.net/~ado_hall/interlingua/gi/parts_of_speech/verb.html#115 §115, "Table of Conjugation"], pp. 38–40.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Word order is [[subject–verb–object]], except that a direct object pronoun or reflexive pronoun comes before the verb (''Io les vide'', 'I see them').<ref name="gode1955"/><ref name="wilgenhof1995"/> Adjectives may precede or follow the nouns they modify, but they most often follow it.<ref name="gode1955"/> The position of adverbs is flexible, though constrained by common sense.<ref name="wilgenhof1995"/>

| |

| | |

| The grammar of Interlingua has been described as similar to that of the Romance languages, but greatly simplified, primarily under the influence of English.<ref name="gode1955"/> More recently, Interlingua's grammar has been likened to the simple grammars of Japanese and particularly Chinese.<ref>Yeager, Leland B., "Artificialitate, ethnocentrismo, e le linguas oriental: Le caso de Interlingua", ''Interlinguistica e Interlingua: Discursos public per Ingvar Stenstrom e Leland B. Yeager'', Beekbergen, Netherlands: Servicio de Libros UMI, 1991.</ref>

| |

| | |

| == Reception ==

| |

| {{multiple issues|section=yes|

| |

| {{POV section|date=September 2019}}

| |

| {{more citations needed section|date=July 2012}}

| |

| }}

| |

| | |

| Critics{{Who|date=January 2010}} argue that, being based on a few [[Standard Average European|European languages]], Interlingua is suitable only for speakers of European languages. Others contend that Interlingua has [[Irregularities and exceptions in Interlingua|spelling irregularities]] that, while internationally recognizable in written form, increase the time needed to fully learn the language, especially for those unfamiliar with [[Indo-European languages]].

| |

| | |

| Proponents{{Who|date=January 2010}} argue that Interlingua's source languages include not only Romance languages but English, German, and Russian as well. Moreover, the source languages are widely spoken, and large numbers of their words also appear in other languages – still more when derivative forms and [[loan translation]]s are included. Tests had shown that if a larger number of source languages were used, the results would be about the same.<ref name="iala1971"/>

| |

| | |

| == Samples ==

| |

| From an essay by Alexander Gode:

| |

| | |

| :''Interlingua se ha distacate ab le movimento pro le disveloppamento e le introduction de un lingua universal pro tote le humanitate. Si on non crede que un lingua pro tote le humanitate es possibile, si on non crede que le interlingua va devenir un tal lingua, es totalmente indifferente ab le puncto de vista de interlingua mesme. Le sol facto que importa (ab le puncto de vista del interlingua ipse) es que le interlingua, gratias a su ambition de reflecter le homogeneitate cultural e ergo linguistic del occidente, es capace de render servicios tangibile a iste precise momento del historia del mundo. Il es per su contributiones actual e non per le promissas de su adherentes que le interlingua vole esser judicate.''<ref>''Novas de Interlingua'', May/June 1958.</ref>

| |

| | |

| :Interlingua has detached itself from the movement for the development and introduction of a universal language for all humanity. Whether or not one believes that a language for all humanity is possible, whether or not one believes that Interlingua will become such a language is totally irrelevant from the point of view of Interlingua itself. The only fact that matters (from the point of view of Interlingua itself) is that Interlingua, thanks to its ambition of reflecting the cultural and thus linguistic homogeneity of the West, is capable of rendering tangible services at this precise moment in the history of the world. It is by its present contributions and not by the promises of its adherents that Interlingua wishes to be judged.

| |

| | |

| {|class="wikitable"

| |

| |+ The [[Lord's Prayer]] | |

| | style="width:10%" | Interlingua | |

| | style="width:10%" | [[Lingua Franca Nova]] | |

| | style="width:10%" | [[Latino sine flexione]] | |

| | style="width:10%" | [[Esperanto]] | |

| | style="width:10%" | [[Ido]] | |

| | style="width:10%" | [[Latin]] | |

| | style="width:10%" | [[Spanish language|Spanish]] | |

| | style="width:10%" | [[Italian language|Italian]] | |

| | style="width:10%" | [[Romanian language|Romanian]] | |

| | style="width:10%" | [[English language|English]] (traditional) | |

| |- | | |- |

| | | | |''IPA''|| {{IPA|[a]}} || {{IPA|b}} || {{IPA|k}}, {{IPA|t͡s}} <sup>1</sup> || {{IPA|[d]}} || {{IPA|[e]}} || {{IPA|f}} || {{IPA|ɡ}} || {{IPA|h}}, {{IPA|∅}} <sup>2</sup> || {{IPA|i}} || {{IPA|ʒ}} || {{IPA|k}} || {{IPA|l}} || {{IPA|m}} || {{IPA|n}} || {{IPA|[o]}} || {{IPA|p}} || {{IPA|k}} <sup>3</sup> || {{IPA|r}} || {{IPA|s}}, {{IPA|z}} || {{IPA|[t]}}, {{IPA|t͡s}} <sup>4</sup> || {{IPA|u}} || {{IPA|v}} || {{IPA|w}}, {{IPA|v}} || {{IPA|[ks]}} || {{IPA|i}} || {{IPA|z}} |

| Patre nostre, qui es in le celos,<br />

| |

| que tu nomine sia sanctificate;<br />

| |

| que tu regno veni;<br />

| |

| que tu voluntate sia facite<br />

| |

| como in le celo, etiam super le terra.<br />

| |

| | | |

| Nos Padre, ci es en sielo,<br />

| |

| sante es tua nome;<br />

| |

| tua renia va veni;<br />

| |

| tua vole va es fada<br />

| |

| en tera como en sielo.<br />

| |

| | | |

| Patre nostro, qui es in celos,<br />

| |

| que tuo nomine fi sanctificato;<br />

| |

| que tuo regno adveni;<br />

| |

| que tuo voluntate es facto<br />

| |

| sicut in celo et in terra.<br />

| |

| | | |

| Patro nia, Kiu estas en la ĉielo,<br />

| |

| sanktigata estu Via nomo.<br />

| |

| Venu Via regno,<br />

| |

| fariĝu Via volo,<br />

| |

| kiel en la ĉielo tiel ankaŭ sur la tero.<br />

| |

| | | |

| Patro nia, qua esas en la cielo,<br />

| |

| tua nomo santigesez;<br />

| |

| tua regno advenez;<br />

| |

| tua volo facesez quale en la cielo<br />

| |

| tale anke sur la tero.<br />

| |

| | | |

| Pater noster, qui es in caelis,<br />

| |

| sanctificetur nomen tuum.<br />

| |

| Adveniat regnum tuum.<br />

| |

| Fiat voluntas tua,<br />

| |

| sicut in caelo, et in terra.<br />

| |

| | | |

| Padre nuestro, que estás en los cielos,<br />

| |

| santificado sea tu Nombre;<br />

| |

| venga a nosotros tu Reino;<br />

| |

| hágase tu Voluntad<br />

| |

| así en la tierra como en el cielo.<br />

| |

| | | |

| Padre nostro che sei nei cieli, <br />

| |

| sia santificato il tuo Nome, <br />

| |

| venga il tuo Regno, <br />

| |

| sia fatta la tua Volontà <br />

| |

| come in cielo così in terra. <br />

| |

| | | |

| Tatăl nostru, Care ești în ceruri, <br />

| |

| sfințească-se numele Tău; <br />

| |

| vie împărăția Ta; <br />

| |

| facă-se voia Ta; <br />

| |

| precum în cer așa și pe Pământ.<br />

| |

| | | |

| Our Father, who art in heaven,<br />

| |

| hallowed be thy name;<br />

| |

| thy kingdom come,<br />

| |

| thy will be done.<br />

| |

| on earth, as it is in heaven.<br />

| |

| |- | | |- |

| | | | |''Names''|| a || be || ce || de || e || ef || ge || ha || i || jota || ka || el || em || en || o || pe || cu || er || es || te || u || ve || duple ve || ix || ypsilon || zeta |

| Da nos hodie nostre pan quotidian,<br />

| |

| e pardona a nos nostre debitas<br />

| |

| como etiam nos los pardona a nostre debitores.<br />

| |

| E non induce nos in tentation,<br />

| |

| sed libera nos del mal.<br />

| |

| Amen.

| |

| | | |

| Dona nosa pan dial a nos,<br />

| |

| pardona nosa pecas,<br />

| |

| como nos pardona los ci peca a nos.<br />

| |

| No condui nos a tentia,<br />

| |

| ma proteje nos de mal.<br />

| |

| Amen.

| |

| | | |

| Da hodie ad nos nostro pane quotidiano,<br />

| |

| et remitte ad nos nostro debitos,<br />

| |

| sicut et nos remitte ad nostro debitores.<br />

| |

| Et non induce nos in tentatione,<br />

| |

| sed libera nos ab malo.<br />

| |

| Amen.

| |

| | | |

| Nian panon ĉiutagan donu al ni hodiaŭ<br />

| |

| kaj pardonu al ni niajn ŝuldojn,<br />

| |

| kiel ankaŭ ni pardonas al niaj ŝuldantoj.<br />

| |

| Kaj ne konduku nin en tenton,<br />

| |

| sed liberigu nin de la malbono.<br />

| |

| Amen

| |

| | | |

| Donez a ni cadie la omnadiala pano,<br />

| |

| e pardonez a ni nia ofensi,<br /> | |

| quale anke ni pardonas a nia ofensanti,<br />

| |

| e ne duktez ni aden la tento,<br />

| |

| ma liberigez ni del malajo.<br />

| |

| Amen

| |

| | | |

| Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie,<br />

| |

| et dimitte nobis debita nostra,<br />

| |

| sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris.<br />

| |

| Et ne nos inducas in tentationem,<br />

| |

| sed libera nos a malo.<br />

| |

| Amen.

| |

| | | |

| Danos hoy nuestro pan de cada día;<br />

| |

| perdona nuestras ofensas,<br />

| |

| así como nosotros perdonamos a quienes nos ofenden;<br />

| |

| y no nos dejes caer en la tentación,<br />

| |

| mas líbranos del mal.<br />

| |

| Amen.

| |

| | | |

| Dacci oggi il nostro pane quotidiano, <br />

| |

| e rimetti a noi i nostri debiti <br />

| |

| come noi li rimettiamo ai nostri debitori, <br />

| |

| e non ci indurre in tentazione, <br />

| |

| ma liberaci dal male. <br />

| |

| Amen.

| |

| | | |

| Pâinea noastră cea de toate zilele, <br />

| |

| dă-ne-o nouă astăzi <br />

| |

| și ne iartă nouă greșelile noastre, <br />

| |

| precum și noi iertăm greșiților noștri, <br />

| |

| și nu ne duce pe noi în ispită <br />

| |

| ci ne izbăvește de cel rău. <br />

| |

| Amin.

| |

| | | |

| Give us this day our daily bread;<br />

| |

| and forgive us our tresspasses<br />

| |

| as we have forgiven those who<br /> trespass against us.<br />

| |

| And lead us not into temptation,<br />

| |

| but deliver us from evil.<br />

| |

| Amen.

| |

| |} | | |} |

|

| |

|

| ==Flags and symbols==

| | # ''c'' is pronounced {{IPA|t͡s}} (or optionally {{IPA|s}}) before "e, i, y" |

| [[File:Flag of Interlingua.svg|thumb|upright|Unofficial flag of Interlingua proposed by Karel Podrazil]]

| | # ''h'' is normally silent |

| [[File:Interlingua2.png|thumb|upright|Another possible flag of Interlingua]] | | # ''q'' only appears in the digraph ''qu'', which is pronounced {{IPA|[kw]}} (but {{IPA|k}} in the conjunction and pronoun ''que'' and pronoun ''qui'') |

| | # ''t'' is generally {{IPA|[t]}}, but ''ti'' followed by a vowel, unless stressed or preceded by "s", is pronounced {{IPA|[t͡sj]}} (or optionally {{IPA|[sj]}}) |

|

| |

|

| As with Esperanto, there have been proposals for a flag of Interlingua;<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20140416192338/http://fotw.net/flags/qy-ia.html Flags of Interlingua (IALA)] from fotw.net (archived URL)</ref> the proposal by Czech translator Karel Podrazil is recognized by multilingual sites.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.airbagjacket.eu/jachetta_airbag.html |title=Toto super le airbag jachetta e gilet / jachetta e gilet con airbag (invento hungaro) - interlingua - All about Airbag Jacket and Airbag Vest |website=Airbagjacket.eu |access-date=2016-06-23}}</ref> It consists of a white four-pointed star extending to the edges of the flag and dividing it into an upper blue and lower red half. The star is symbolic of the four cardinal directions, and the two halves symbolize Romance and non-Romance speakers of Interlingua who understand each other.

| | For the most part, consonants are pronounced as in English, while the vowels are like Spanish. Double consonants are pronounced as single. Interlingua has five falling diphthongs, {{IPA|/ai/, /au/, /ei/, /eu/}}, and {{IPA|/oi/}},<ref>Gopsill, F. P., ''Interlingua today: A course for beginners'', Sheffield, UK: British Interlingua Society, 1994.</ref> although {{IPA|/ei/}} and {{IPA|/oi/}} are rare. |

|

| |

|

| Another symbol of Interlingua is the ''[[Blue Marble]]'' surrounded by twelve stars on a black or blue background, echoing the twelve stars of the [[Flag of Europe]] (because the source languages of Interlingua are purely European).

| | Unassimilated foreign loanwords, or borrowed words, are pronounced and spelled as in their language of origin. Their spelling may contain diacritics, or accent marks. If the diacritics do not affect pronunciation, they are removed. |

|

| |

|

| ==See also== | | == Morphology == |

| * Comparisons with other languages

| | {{Main|Interlingua/Morphology}} |

| ** [[Comparison between Esperanto and Interlingua]]

| |

| ** [[Comparison between Ido and Interlingua]]

| |

| * Publications

| |

| ** ''[[Grammatica de Interlingua]]''

| |

| ** ''[[Interlingua, Instrumento Moderne de Communication International]]'' (course manual)

| |

| ** [[Interlingua dictionaries]]

| |

| * Vocabulary

| |

| ** [[Classical compound]]

| |

| ** [[Hybrid word]]

| |

| ** [[Internationalism (linguistics)]]

| |

| ** [[List of Greek and Latin roots in English]]

| |

| ** [[Medical terminology]]

| |

| * [[Irregularities and exceptions in Interlingua]]

| |

| * [[Willem Jacob Visser]]

| |

|

| |

|

| ==References==

| | Word order is SVO, except that a direct object pronoun or reflexive pronoun comes before the verb. Adjectives may precede the noun they modify, but they most often follow it. The position of adverbs is flexible. The grammar of Interlingua is similar to that of the Romance languages, but greatly simplified, under the influence of English. |

| {{Reflist}}

| |

|

| |

|

| ==Sources== | | == Lexicography == |

| * Falk, Julia S. ''Women, Language and Linguistics: Three American stories from the first half of the twentieth century.'' Routledge, London & New York: 1999. | | * [[Interlingua/Swadesh]] |

| * {{cite book|last=Gode|first=Alexander|author-link=Alexander Gode|author2=Hugh E. Blair|author2-link=Hugh E. Blair|title=Interlingua; a grammar of the international language|url=https://archive.org/details/interlinguagramm00gode|access-date=2007-03-05|edition=Second|orig-year=1951|year=1955|publisher=Frederick Ungar Publishing|location=[[New York City|New York]]|isbn=0-8044-0186-1|oclc=147452}}

| |

| * Gopsill, F.P. [https://web.archive.org/web/20091027145739/http://geocities.com/hkyson/directorio/interlinguistica/html/lehistoriahtml.htm ''Le historia antenatal de Interlingua.'']. (In Interlingua.) Accessed 28 May 2005.

| |

| * International Auxiliary Language Association (IALA). [https://web.archive.org/web/20040702192153/http://www.interlingua.fi/ialagr45.htm ''General Report'']. IALA, New York: 1945.

| |

| * {{cite book|author=International Auxiliary Language Association|author-link=International Auxiliary Language Association|editor=Alexander Gode|editor-link=Alexander Gode|others="Foreword" and "Acknowledgements" by Mary Connell Bray|title=Interlingua-English; a dictionary of the international language|url=http://www.bowks.net/worldlang/aux/b_IED.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071227051537/http://www.bowks.net/worldlang/aux/b_IED.html |archive-date=2007-12-27|access-date=2010-04-18|edition=Second|orig-year=1951|year=1971|publisher=Frederick Ungar Publishing|location=[[New York City|New York]]|isbn=0-8044-0188-8|oclc=162319}}

| |

| * Pei, Mario. ''One Language for the World and How To Achieve It.'' Devin-Adair, New York; 1958.

| |

| * Union Mundial pro Interlingua (UMI). [http://www.interlingua.com/historia/index.html ''Interlingua 2001: communication sin frontieras durante 50 annos''] (in Interlingua). Accessed 17 August 2006.

| |

|

| |

|

| ==External links==

| | The form of an Interlingua word is considered an international prototype with respect to the other words. On the one hand, it should be neutral, free from characteristics peculiar to one language. On the other hand, it should maximally capture the characteristics common to all contributing languages. As a result, it can be transformed into any of the contributing variants using only these language-specific characteristics. If the word has any derivatives that occur in the source languages with appropriate parallel meanings, then their morphological connection must remain intact; for example, the Interlingua word for 'time' is spelled ''tempore'' and not ''*tempus'' or ''*tempo'' in order to match it with its derived adjectives, such as temporal. |

| {{InterWiki|code=ia}}

| |

| {{sisterlinks|d=Q35934|voy=no|species=no|m=no|mw=no|commons=Category:Interlingua|n=no|q=no|s=no}}

| |

| * {{Official website|http://www.interlingua.com/}}

| |

| * {{curlie|Science/Social_Sciences/Linguistics/Languages/Constructed/International_Auxiliary/Interlingua/}} | |

| * [http://rudhar.com/lingtics/intrlnga/resurses.htm Collection of links to Interlingua resources] | |

|

| |

|

| {{Constructed languages|state=collapsed}}

| | The language-specific characteristics are closely related to the sound laws of the individual languages; the resulting words are often close or even identical to the most recent form common to the contributing words. This sometimes corresponds with that of Vulgar Latin. At other times, it is much more recent or even contemporary. It is never older than the classical period. |

| {{Authority control}}

| |

|

| |

|

| [[Category:Interlingua| ]]

| | {{Aquatiki}} |

| [[Category:International auxiliary languages]] | | [[Category:Universal Languages]] |

| [[Category:Constructed languages]] | | [[Category:Interlingua]] |

| [[Category:Fusional languages]]

| | [[Category:Languages]] |

| [[Category:Constructed languages introduced in the 1950s]]

| | [[Category:Romance]] |

| [[Category:1951 introductions]] | |

| [[Category:Romance languages]] | |