Chlouvānem: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| (412 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{movedon}} | |||

{{Infobox language | {{Infobox language | ||

|name = Chlouvānem | |name = Chlouvānem | ||

| | |nativename = chlǣvānumi dhāḍa | ||

|pronunciation = | |pronunciation = c͡ɕʰɴ̆ɛːʋaːnumi dʱaːɖa | ||

| | |pronunciation_key = IPA | ||

|region = | |creator = User:Lili21 | ||

|created = Dec 2016 | |||

|region = Jahībušanā, southern Vaikēham, eastern half of Araugi, southernmost Vīṭadælteh | |||

|ethnicity = Chlouvānem | |ethnicity = Chlouvānem | ||

|speakers = {{formatnum: | |speakers = {{formatnum:1905000000}} | ||

|date = | |date = 3874 <small>(6424<sub>10</sub>)</small> | ||

|setting = [[Verse:Calémere|Calémere]] | |setting = [[Verse:Calémere|Calémere]] | ||

|familycolor = | |familycolor = Hmong-Mien<!--This is to add the family colour! HEX codes don't work, so I chose the closest family colour to your provided Hex Code<nowiki>!</nowiki>--> | ||

|fam1 = [[Lahob languages|Lahob]] | |fam1 = [[Lahob languages|Lahob-Imuniguronian]] | ||

| | |stand1 = Classical Chlouvānem | ||

|script = Chlouvānem script (''chlǣvānumi jīmalāṇa'') | |||

|script = | |nation = [[Verse:Chlouvānem Inquisition|lands of the Inquisition]], Brono, Fathan, <small>Qualdomailor, Gorjan (regional)</small> | ||

|nation = [[Verse:Chlouvānem Inquisition|lands of the Inquisition]], Brono, Fathan | |agency = Inquisitorial Office of the Language (''dhāḍi plušamila'') | ||

|agency = Inquisitorial Office of the Language ( | |image = Flag of the Inquisition.png | ||

|imagealt = Flag of the Inquisition | |||

|notice=IPA | |||

}} | }} | ||

'''Chlouvānem''', natively '''chlǣvānumi | '''Chlouvānem''', natively '''chlǣvānumi dhāḍa''' ("language of the Chlouvānem people"), sometimes also called '''naviṣidhāḍa''' (lit. "language of the [Holy] Book(s)") or '''mālnadhāḍa''' (lit. "language of the Union") by non-Chlouvānem users, is the most spoken language on the planet of [[Verse:Calémere|Calémere]] (Chl.: ''Liloejāṃrya''). It is the official language of the Inquisition (''murkadhānāvi'') and its country, the [[Verse:Chlouvānem Inquisition|Chlouvānem lands]] (''chlǣvānumi babhrām''<ref>Commonly ''murkadhānāvīyi babhrām'' “Land of the Inquisition”, officially referred to as ''chlǣvānumi murkadhānāvīyi babhrām'' “Land(s) of the Chlouvānem Inquisition” or as ''chlamiṣvatrī maijuniāvyumi murkadhānāvīyi stalyāmite kailibabhrām'' "Pure Lands under Guidance of the Inquisition of the Descendants of the Chlamiṣvatrā".</ref>), the main lingua franca across vast areas of Márusúturon (according to the Chlouvānem definition all of Jahībušanā, the eastern half of Araugi, southern Vaipūrja, and far southernmost Vīṭadælteh) - most importantly Brono, Fathan, Qualdomailor, and all other countries of the former Kaiṣamā, and, due to cultural exchanges and influences in the last seven hundred years, also a well known language in Greater Skyrdagor.<br/>It is the [[Verse:Yunyalīlta|Yunyalīlti religion]]'s liturgical language. | ||

The language currently known as Chlouvānem was first attested about 2400 years ago in documents from the Lällshag civilization, as the language of a [[Lahob languages|Lahob-speaking]] people that settled in the southern part of the | The language currently known as Chlouvānem was first attested about 2400 years ago in documents from the Lällshag civilization, as the language of a [[Lahob languages|Lahob-speaking]] people that settled in the southern part of the Nīmbaṇḍhāra-Lāmberah plain, particularly near Lake Lūlunīkam. Around year 4000 of the Chlouvānem calendar (itself an adaptation of the Lällshag one), the ''Chlamiṣvatrā'', the great Prophet of the Yunyalīlta, lived and taught her doctrine in the Chlouvānem language, paving the way for it to gain the role of most important language and lingua franca in the at the time massively linguistically fragmented lower Plain. While the Chlamiṣvatrā's language is what we now call "Archaic Chlouvānem" (''chlǣvānumi sārvire dhāḍa''), most of the Yunyalīlti doctrine as we now know it is in the later stage of Classical Chlouvānem (''chlǣvānumi lallapårṣire dhāḍa''), a koiné developed in the mid-5th millennium. Since then, for nearly two millennia, this classical language has been kept alive as the lingua franca in the Yunyalīlti world, resulting in the state of diglossia that persists today. | ||

Despite the fact that local vernaculars in | Despite the fact that local vernaculars in the Inquisition are in fact daughter languages of Chlouvānem, creoles based on it, or completely unrelated languages, the ''chlǣvānumi dhāḍa'' is a fully living language as every Chlouvānem person is bilingual in it and in the local vernacular. About 1,9 billion people on the planet define themselves as native Chlouvānem speakers, more than for any other Calémerian language. | ||

Chlouvānem (not counting separately its own daughter languages) is by far the most spoken of the [[Lahob languages]] (more than 99.98% of Lahob speakers), and the only one of the family to have been written before the contemporary era. It is, however, the geographical outlier of the family, due to the almost 10,000 km long migration of the Ur-Chlouvānem from the Proto-Lahob homeland at the northern tip of Evandor. Chlouvānem, due to its ancientness, still retains much of the complex morphology of Proto-Lahob, but its vocabulary has been vastly changed by language contact, especially after the Chlouvānem settled in the Plain, where they effectively became a métis ethnicity by intermixing with neighboring peoples | Chlouvānem (not counting separately its own daughter languages) is by far the most spoken of the [[Lahob languages]] (more than 99.98% of Lahob speakers), and the only one of the family to have been written before the contemporary era. It is, however, the geographical outlier of the family, due to the almost 10,000 km long migration of the Ur-Chlouvānem from the Proto-Lahob homeland at the northern tip of Evandor. Chlouvānem, due to its ancientness, still retains much of the complex morphology of Proto-Lahob, but its vocabulary has been vastly changed by language contact, especially after the Chlouvānem settled in the Plain, where they effectively became a métis ethnicity by intermixing with neighboring peoples. | ||

→ ''See [[Chlouvānem/Lexicon|Chlouvānem lexicon]] for a list of common words.'' | → ''See [[Chlouvānem/Lexicon|Chlouvānem lexicon]] for a list of common words grouped by theme.'' | ||

== | {{Chlouvānem sidebar}} | ||

==Internal history== | |||

The history of the Chlouvānem language itself is tightly linked with the one of the Ur-Chlouvānem (''odhāḍadumbhais'') and Chlouvānem (''chlǣvānem'') peoples, and is usually divided in the following periods: | |||

* Proto-Lahob (''hūlisakhāni odhāḍa''; PLB for short) | |||

* Pre-Chlouvānem or Ur-Chlouvānem language (''ochlǣvānumi dhāḍa'' or rarely ''chlǣvānumi odhāḍa'') | |||

* Archaic Chlouvānem (''chlǣvānumi sārvire dhāḍa'') | |||

* Classical Chlouvānem (''chlǣvānumi lallapårṣire dhāḍa'') | |||

* Post-Classical (''chlǣvānumi paṣlallapårṣire dhāḍa'') and Modern (''~ amyærlairī ~'') Chlouvānem. | |||

===Proto-Lahob=== | |||

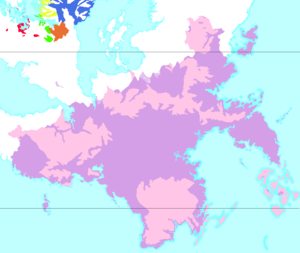

[[File:Lahob languages.png|thumb|The spread of [[Lahob languages]] in Márusúturon. The Chlouvānem-speaking area is in lilac and pink.]] | |||

Chlouvānem and its daughter languages' nearest sibling languages are the other [[Lahob languages]], with a speaker count in the tens of thousands and spoken in the traditional villages of the indigenous peoples of a subpolar area in northwestern Márusúturon, straddling the Orcish Straits between 55º and 70ºN, nearly 10,000 km away from the attested Chlouvānem heartlands. The most recent common ancestor between Chlouvānem and these languages is known as Proto-Lahob (''ohūlisakhāni dhāḍa''), and was spoken approximately 4000 to 3500 years before the present. The location where Proto-Lahob speakers probably lived is, for sure, neither the Chlouvānem heartlands nor the current territories of other Lahob peoples; instead, there are three hypothetical areas where it could have been spoken: | |||

# on the western coast of the Skyrdegan Inner Sea, roughly between 40º and 45ºN (in modern day Aqalyšary and Berkutave, perhaps reaching north into modern Morufalhay) – this hypothesis is usually given along with an earlier estimated date for the proto-language; | |||

# in the southern Ulšan Mountains, in present-day Kŭyŭgwažtov (nowadays not quite accepted as the other two); | |||

# on the western coast of the High Ivulit (in modern Leñ-ṱef), just opposite modern Qualdomailor. | |||

No matter which of these was the "birthplace" of Lahob peoples, the modern groups that survived are those that had migrated from the original homeland, as the spread of various other groups in the following millennia - Uyrǧan, Berko-Tarastian, Samaidulic, and most notably the Kenengyry much later - displaced and eventually assimilated the remnant groups<ref>Each of these peoples displaced the previous ones, resulting in this area of Calémere having today a dominance of Kenengyry languages, but with many minority languages in between, or of different families at its borders; the Uyrǧan family, for instance, is today composed of two sub-families 5000 km apart.</ref>. | |||

Reconstructed vocabulary and the current state of the Lahob peoples of the Far North makes us reconstruct the Proto-Lahob society as a non-urban civilization, possibly with rudimental agriculture only, with the only reconstructable "agricultural" terms being a root for "to plant, (cultivate?)" – ''*tɬewkj-'' – and a word for a cereal, likely "wheat" or "rye", ''*kawŋədot'' (most languages reflect it as the word for "rye", but Chlouvānem and the southernmost Core Lahob ones reflect it as "wheat"). The semi-nomadic lifestyle was prevalent, but population growth eventually proved enough to lead some tribes to migrate. Unsurprisingly, the geographical terms are consistent with a temperate, semi-arid location as those hypothesized; names of plants, trees, and animals are mostly only reconstructible from the Core Lahob languages, and if Chlouvānem has kept some they have mostly been generalized or shifted to similar elements in the Ur-Chlouvānem's new homeland. | |||

Chlouvānem is mainly | Notably, a few Proto-Lahob loanwords are found in Proto-Samaidulic and Proto-Fargulyn, which means they often have cognates in other major languages such as [[Skyrdagor]], [[Brono-Fathanic]], or [[Qualdomelic]]. The main Lahob ethnonym, *ɬakʰober ("group, tribe, villabe", Chl. ''chlågbhah'' "clan, tribe, (archaic: rural village, esp. if in areas poorly suited to agriculture)"), for example, is also found in Proto-Fargulyn as *laq'obɨr, and has reached modern Skyrdagor as ''lokjur'' "farmstead". These borrowings are often cited as a point towards placement of the Lahob homeland by the High Ivulit, as the homelands of both Proto-Samaidulic and Proto-Fargulyn are also hypothesized to be in the area (even if they are also contested). | ||

===Ur-Chlouvānem=== | |||

''Pre-Chlouvānem'', ''Proto-Chlouvānem'', or ''Ur-Chlouvānem'' (''ochlǣvānumi dhāḍa'') is the term for the unattested stage of Chlouvānem in the millennium between the end of the common Proto-Lahob period and either the settlement in the Inland Jade Coast, in the lands ultimately drained by Lake Lūlunīkam, or the first attestation of the existence of the Chlouvānem people, in a [[Lällshag]] inscription dated around 3850~3900, approximately 200 years before the lifetime of the Chlamiṣvatrā and a bit less than half a millennium before the founding of the Inquisition. | |||

The trek of the Ur-Chlouvānem across Márusúturon was likely carried out by a series of tribes, some of whose likely settled in places along the route; the long route most likely passed through Tiṃhayāla Pass, between present-day Maišikota and Nālaṭhirūṇa, which is one of the most important passes of the whole continent, a relatively low crossing between the plains of Līnajaiṭa and, therefore, the Little Ivulit, and the upper reaches of the Nīmbaṇḍhāra, leading to the whole Great Chlouvānem Plain. Therefore, the long trek of the Ur-Chlouvānem was, except for this pass, mainly in flat territory, facilitating their migration. | |||

Linguistically, Ur-Chlouvānem was very conservative, retaining most traits of Proto-Lahob morphology. However, it did develop some traits unique to Chlouvānem, not present in the Core Lahob languages: | |||

* the loss of gender agreement, with gapped relative clauses replacing adjective+noun constructions; | |||

* the cliticization of some verbal forms, leading to the development of most verbal modifiers, including the interior/exterior verb forms and evidentials; | |||

* the topic-comment syntax. | |||

Grammatically, ablaut became less pronounced, as the ablaut class of nouns and all ablauting verbal classes except for class 2 became mostly unproductive (with a few exceptions).<br/> | |||

Phonetically, Ur-Chlouvānem retained most consonant phonemes of Proto-Lahob, losing one point of articulation for stops (the labiovelar) but gaining a new one (the retroflex). At least one phoneme, the glottal stop, was introduced through borrowings. Vowels saw more changes, with Proto-Lahob *a *ā and *o *ō merging into /ä/, as well as peculiar developments for vowels, leading to the emergence of front rounded vowels in the Ur-Chlouvānem stage which, however, became unrounded well before the earliest attestations, like PLB ''*hōwrar'' "summer" → UrChl. *[høʏ̯ʀaχ] → Chl. ''heirah'' "year"; these are not to be confused with the attested front rounded vowels, which are a later development, in non-Standard, Classical-era dialects, such as Lūlunīkami ''fülde'', ''fǖldöy'' [ɸyɴ̆de] [ɸyːɴ̆døʏ̯] for standard ''ħulde'', ''ħildoe'' ("to play", "game") ← PLB ''*pʰɨʕəd-ke'', ''*pʰɨːʕədõ''. | |||

Lexically, Ur-Chlouvānem borrowed a lot of word roots from other, otherwise unattested languages: while the grammar of Chlouvānem is unmistakeably Lahob, a lot of its vocabulary isn't, and a large number of its roots (about 25%) has not been traced to either Proto-Lahob or to any known language of the new homeland. Note, though, that this does not mean they are certainly from other languages: they may be Lahob words lacking a cognate in any surviving Core Lahob language, or borrowings from a minor language of their migration destination not attested otherwise. Such vocabulary is found in every semantic field, including animals (''yoñšam'' "donkey"; ''snīdbhas'' "bull") and general natural things or cultural products (''brāṣṭhis'' "stream", ''gurḍhyam'' "flute"), but often clearly related to an agrarian society (''nakthum'' "storage", ''vaiṣrya'' "plough"). | |||

===Archaic and Classical Chlouvānem=== | |||

Archaic Chlouvānem (''chlǣvānumi sārvire dhāḍa'') is the language that emerged from the métis people that formed in the inland Jade Coast in the second half of the 4th millennium through intermixing of the Ur-Chlouvānem with local peoples. In the space of a few centuries, various peoples with different origins came to form a rather culturally homogeneous mass that was further united by the birth of a common religion – the [[Verse:Yunyalīlta|Yunyalīlta]] – among them, and by the founding of their first states under the impulse of the Inquisition. Most anthropologists of Calémere are concord in considering that the Lahob heritage of the Chlouvānem is mostly limited to their language, with nearly every other aspect of their culture, and most of their genetic stock, being markedly different from the surviving Core Lahob peoples. | |||

Nearly all of the Chlouvānem vocabulary for their homeland is non-Lahob in origin, with, however, some notable Lahob words in what concerns religion: ''yunya'', for example, is an inherited Lahob word (PLB ''*šjunjo''), and the compound ''lillamurḍhyā'' is entirely made of Lahob roots (the compound itself was made in Lūlunīkami, not in the dialect that became Standard Chlouvānem). | |||

==Variants== | ==Variants== | ||

Chlouvānem as spoken today is the standardized version of the literary language of the | Chlouvānem as spoken today is the standardized version of the literary language spoken in the mid-5th millennium along the lower course of the ''Nīmbaṇḍhāra'' river, the one in which most sacred texts of the Yunyalīlta are written. Since then, the language has been kept alive for more than 1500 years and counting in a diglossic state with many descendant and creole languages developing in the areas that gradually came under Chlouvānem control, and Classical Chlouvānem is in fact [[Verse:Chlouvānem Inquisition#Chlouvānem ethnicity|a major defining factor of Chlouvānem ethnicity]], enabling the existence of a single cultural area spread across half a continent despite the individual areas each having their own vernaculars. | ||

[[ | The Chlouvānem-speaking world may be described, [[w:World_Englishes#Kachru's_Three_Circles_of_English|much like English]], as being divided into three circles with different speaker profiles: | ||

* The "inner circle" is the area where Chlouvānem is the only official language for intranational communication, acting as the high variant in a state of diglossia with local vernaculars. Therefore, this circle includes the whole Chlouvānem Inquisition, most of its external territories, plus a few areas with Chlouvānem majority elsewhere (parts of Qualdomailor and Kŭyŭgwažtow); | |||

* The "outer circle" includes the whole of the former Kaiṣamā (except for Taruebus and Gorjan), where Chlouvānem had been a semi-official language during the Union and, while it is not the primary language of the majority, its use in society is too high to be described simply as a foreign language - for example, Chlouvānem is the main language (or at least has a usage comparable to the main official language(s)) in higher education and particular fields of politics. | |||

* The "expanding circle" is the area where Chlouvānem is not official but a reasonable amount of people uses it, with adequate proficiency, for international communication. This circle includes Greater Skyrdagor and Taruebus (when the proficiency is higher and closer to outer circle areas, to the extent that Chlouvānem language teachers and professors in the West are more often Skyrdegan than actual Chlouvānem), as well as most countries aligned with the Eastern bloc in Védren and far western Márusúturon. | |||

===Pronunciations=== | ===Pronunciations=== | ||

All true dialects of Chlouvānem eventually developed into distinct vernaculars, so that the diatopical variation of contemporary Chlouvānem are referred to as '''pronunciations''' (in Chl. ''babhrāyāṃsai'', sg. ''babhrāyāṃsa'', literally "land-sound"), a somewhat misleading term given that they do not just vary in pronunciation (with prosody being often the main point of divergence), but even more in vocabulary.<br/> | |||

Pronunciations are grouped in broad areas which more or less overlap with the cultural macroregions (the administrative Tribunals) and with the distribution of the subgroupings of the Chlouvānem ethnicity. Local pronunciations are generally not tied to a specific ethnic group, only to the area they're spoken in, and they show significantly less variation than vernaculars. | |||

Chlouvānem pronunciations are generally grouped as follows: | |||

* Jade Coastal, Eastern Plain, and Southern (''lūṇḍhyalimvi naleidhoyi no nyuvyuñci no''), broadly corresponding to the tribunals of the Jade Coast, Southern Plain, the South, the Eastern Plain, the Līrah River Hills, and parts of the Northern and Central Plain. Standard Chlouvānem is based on one of these pronunciations; | |||

* Western Plain (''samvāldhoyi''), corresponding to the tribunals of the Western Plain, parts of the Northern and Central Plain, and the Inland Southwest; | |||

* Southeastern (''talehiyuñci''), used in the tribunals of the Near East, the Southern Far East, and the Southeastern Islands; | |||

* Eastern (''nalejñuñci''), used in the Northern Far East and in the East; | |||

* Northeastern and Hålvarami (''helaṣyuñci hålvarami no''), used in the Northeast and in the Hålvaram plateau; | |||

* Sand Coastal (''chleblimvi''), including the pronunciations of the Coastal Southwest, small parts of the Inland Southwest, and the eastern part of the Western tribunal; | |||

* Western (''samvālyuñci''), in most of the West and in the Far West (the eastern part of the historical Dabuke areas). | |||

The remaining areas are those of more recent Chlouvānemization, and aside from not having a distinct subgroup of the Chlouvānem ethnicity, they also don't have distinct pronunciation features, being closer to Standard Chlouvānem. Many of these areas also don't have a general Chlouvānem-derived vernacular and so in urban areas the standard language is used even in the most informal contexts. These areas include Hokujaši and Aratāram island as well as Kēhamijāṇa in the Northeast; the Hivampaida and Måhañjaiṭa in the North; virtually all of the Northwest; and the two island groups not part of any tribunal: the Kāmilbausa islands due south of the Western tribunal and the Kāyīchah islands off the eastern coast of Védren.<br/>Chlouvānem as spoken in countries of the former Kaiṣamā (and especially Kŭyŭgwažtow) is sometimes included in this category, although the prominence of contact with the local official languages has rendered those variants quite distinct in vocabulary and sometimes in the phonemic inventory too. | |||

===Vernaculars=== | ===Vernaculars=== | ||

Most local vernaculars of the Inquisition (''babhrāmaivai'', sg. ''babhrāmaiva'', literally “land word(s)”) are, linguistically, the daughter languages of Classical Chlouvānem. They are the result of normal language evolution with, in most areas, enormous influences by substrata. | |||

Actually, only a bit more than half of the Inquisition has a vernacular that is a true daughter language - most areas conquered in the last 600 years, thus since the | Actually, only a bit more than half of the Inquisition has a vernacular that is a true daughter language - most areas conquered in the last 600 years, thus since the late 6th millennium, speak a creole language, with an almost completely Chlouvānem lexicon and a grammar which shows simplifications and Chlouvānem-odd traits uncommon to languages of the heartlands. It is however widely agreed on that the Eastern Chlouvānem languages, despite being considered true daughter languages, have a large and long creolization history. | ||

The main division for local vernaculars - or Chlouvānem languages - is the one in groups, as few of them are standardized and large areas are dialect continua where it is extremely difficult to determine which dialects belong to a particular language and which ones do not. Furthermore, most people speak of their vernacular as “the word of [village name]”, and always refer to them as local variants of the same Chlouvānem language, without major distinctions from the national language which is always Classical Chlouvānem<ref>It's just as if speakers of Parisian French, Florentine Tuscan and Carioca Brazilian would still say they spoke dialects of (Classical) Latin.</ref>. Individual “languages” are thus simply defined starting from the diocese they’re spoken in, so for example the Nanašīrami language includes all dialects spoken in the diocese of Nanašīrama, despite those spoken in the eastern parts of the diocese being closer to those spoken in | The main division for local vernaculars - or Chlouvānem languages - is the one in groups, as few of them are standardized and large areas are dialect continua where it is extremely difficult to determine which dialects belong to a particular language and which ones do not. Furthermore, most people speak of their vernacular as “the word of [village name]”, and always refer to them as local variants of the same Chlouvānem language, without major distinctions from the national language which is always Classical Chlouvānem<ref>It's just as if speakers of Parisian French, Florentine Tuscan and Carioca Brazilian would still say they spoke dialects of (Classical) Latin.</ref>. Individual “languages” are thus simply defined starting from the diocese they’re spoken in, so for example the Nanašīrami language includes all dialects spoken in the diocese of Nanašīrama, despite those spoken in the eastern parts of the diocese being closer to those spoken in Takajñanta than to the Nanašīrami dialect of [[Verse:Chlouvānem Inquisition/Līlasuṃghāṇa|Līlasuṃghāṇa]] - which has, however, lots of common points with the Lanamilūki Valley dialects of Talæñoya to the south.<br/> Note that the word ''maiva'', in Chlouvānem, only identifies a language spoken in a certain area which is typically considered to belong to a wider language community, independent of its origin. It does not have any pejorative meaning of stigmatization, unlike examples like e.g. ''lingua'' vs. ''dialetto'' in Italian. | ||

Main local vernaculars by macroarea (Tribunal): | |||

* Eastern Plain | * '''Jade Coast, Eastern Plain, Northern Plain, parts of the Central Plain''' | ||

* | ** Eastern Plain and Jade Coast dialect continuum (''naleidhoyi lūṇḍhyalimvi no maivai'') — spoken in the eastern half of the Nīmbaṇḍhāra plain, the Jade Coast (littoral and interior), and the northern part of the rainforest. If Chlouvānem itself is not counted as being spoken natively, then this dialect continuum constitutes Calémere's most spoken language by number of native speakers. | ||

* | ** Northern Plain dialect continuum (''kehaṃdhoyi maivai'') — spoken in the northern Nīmbaṇḍhāra plain, in the foothills of the Camipāṇḍa mountains. It has traits of both the Eastern Plain and the Western Plain continua, but also has its odd features common throughout the area but lacking in the other two groups. However, due to internal migration, the linguistic border is rather odd, especially the one with the Eastern Plain continuum: the contemporary vernacular of Mamaikala, the largest city of the Northern Plain, as well as nearby areas on the mid-Lāmberah river, is undoubtedly Eastern, despite being well into Northern-speaking territory.<br/>The areas from the Namaikaheh eastwards beyond the Līrah river were, in South Márusúturonian Antiquity, the heartlands of civilizations speaking Dayleshi languages: Ancient Namaikahi, Nenesic, and Pyotic. While these were written administrative languages at the time, and kept being used alongside Chlouvānem in the first centuries of Chlouvānemization, they left no descendants. While the amount of Dayleshi loanwords into Classical Chlouvānem is negligible, Dayleshi substrata have been identified for nearly the entirety of the Northern Plain dialect continuum<ref>The toponym ''Namaikaheh'' for the Northern Plain (most of the Lāmberah valley) is itself borrowed from the Lällshag adaptation of the original Ancient Namaikahi word.</ref>. | ||

* | * '''Western Plain, Inland Southwest, parts of the Central Plain''' | ||

* Near Eastern ('' | ** Western Plain dialect continuum (''samvāldhoyi maivai'') — spoken in the western half of the Nīmbaṇḍhāra plain, including the majority of the Inland Southwest. | ||

* Far | ** Southwestern Plain dialect continuum (''māħimdhoyi maivai'') — spoken in the southwestern part of the plain and small parts of the Inland Southwest. Unlike other Chlouvānem-origin dialect continua, these are the daughter languages not of Chlouvānem (indigenous - as in the Jade Coast - or introduced), but of the closely related Western Ancient Chlouvānem. | ||

* | * '''South and Coastal Southwest''' | ||

* | ** Jungle language (''nanaimaiva'') — term for the Chlouvānem daughter language spoken across most of the South, including nearby islands. Due to the historical importance of Hālyanēṃṣah and Lūlunimarta in the Chlouvānem Age of Discovery, the ''nanaimaiva'' is sometimes considered one of the most prestigious vernaculars and, almost uniquely for a Chlouvānem vernacular, it has contributed quite a few words to foreign languages. A number of dialects derived from Lūlunimarti known by the name of ''Kaikhūñi'' are spoken in various linguistic islands on the coast of the Far East, in historic trading posts of the Lūlunimarti Republic. | ||

* | ** Many inland villages in the rainforest have their own local language, often not related to Chlouvānem. Large parts of the area are therefore trilingual, with the local language being spoken alongside Classical Chlouvānem and a local ''nanaimaiva'' dialect - often described as being "Hālyanēṃṣah-type", "Kælšamīṇṭa-type", or "Lūlunimarta-type" from its similarity to the three main dialects. | ||

** Sand Coast dialect continuum (''chleblimvi maivai'') — spoken across the Sand Coast, i.e. the Coastal Southwest tribunal. The dialects of Vāstarilīmva, at the southwesternmost tip of the main subcontinental body, have mixed Sand Coastal and ''nanaimaiva'' traits. | |||

* '''Near East''' | |||

** Near Eastern dialect continuum (''mūtyānalejñutei maivai'') — a dialect continuum spoken in the Near East, the area roughly between Āgrajaiṭa and Yambrajaiṭa in the west and the Cāllikāneh mountains in the east. | |||

** Rǣrumi (''ræ:æron u xæræž''; Chl.: ''rǣrumi dhāḍa'') — the Fargulyn language (distantly related to [[Skyrdagor]]) of the historically nomadic Rǣrai, which were settled in Kaiṣamā times in a hilly area between the Near East and the Northern Far East, nowadays the semi-ethnic diocese of Rǣrajāṇai. | |||

** Kanoë-Pulin languages (''kanoyēpulin ga dhāḍai'') — a language family mostly spoken in the Kahaludāh mountains and hills in Yarañšūṇa, Tumidajaiṭa, and parts of Kotaijaiṭa and Naitontā. Tumidumi (''sokaw y eetumið''; Chl. ''tumidumi dhāḍa''), spoken by the Tumidai people of the ethnic diocese of Tumidajaiṭa, is by far the most spoken. | |||

** Kotayumi (''kotaii šot''; Chl. ''kotayumi dhāḍa'') — a Yalikamian language (likely distantly related to the Kanoë-Pulin family) spoken by the Kotayai, indigenous people of the ethnic diocese of Kotaijaiṭa. | |||

** Kitaldian languages (''kitaludumi dhāḍai'') – historically spoken in southern Pēmbajaiṭa, in the Rǣrajāṇai, and in most of western and northern Lakṝṣyāṇa; this remains their present-day distribution, but mostly in rural and mountainous areas. | |||

* '''Southern Far East and Southeastern islands''' | |||

** Katamadelī (''katamadelī maivai'') — dialect continuum of Chlouvānem daughter languages spoken on the western coast of the Far East and its interior, from far southern Pēmbajaiṭa up to the southeasternmost tip near Ehaliħombu. ''Katamadelē'' is a traditional, pre-Chlouvānem name for today's Lakṝṣyāṇa diocese, later extended to the whole area. | |||

** Naleilimvi (''naleilimvi maivai'') — the dialect continuum of Chlouvānem daughter languages spoken - as the name says - on the eastern coast (''naleilimva'') of the Far East, from Torašitā in the north to Daihāgaiya in the south. | |||

** Hūnakañumi (''huwănaganь sisāt''; Chl. ''hūnakañumi dhāḍa'') — the Yalikamian language of the Hūnakañai, the indigenous people of the ethnic diocese of Hūnakañjaiṭa; as with many Near- and Far Eastern languages, it belongs to the Yalikamian languages. It is however spoken only in sparsely populated hilly areas, and the diocese is predominantly Chlouvānem, including the macroregional metropolis and tenth-largest city of the Inquisition, Līlekhaitē. | |||

** Tendukumi (''tănduk sisod''; Chl. ''tendukumi dhāḍa'') — a Yalikamian language spoken by the Tendukai people of the ethnic diocese of Tendukijaiṭa. By percentage of speakers in its native area, it is one of the most spoken languages among officially recognized ones in ethnic diocese, with about 41% of people in Tendukijaiṭa speaking it. The diocese, however, is the least populated in the tribunal. | |||

** Niyobumi (''niyyube sesaϑ''; Chl. ''niyobumi dhāḍa'') — a Yalikamian language spoken in the hilly areas of Niyobajaiṭa ethnic diocese. | |||

** other Yalikamian languages (''yalikamyumi dhāḍai'') – thirteen indigenous languages in Yamyenai as well as Kondabumi, which is however often considered a transitional dialect continuum between Hūnakañumi and Tendukumi. | |||

** Kaldaic languages (''kaldani dhāḍai'') – before Chlouvānemization, the main language family spoken on the littoral from central-eastern Lakṝṣyāṇa to Daihāgajña; in most of Hūnakañjaiṭa it was first replaced by Hūnakañumi, whose speakers came from inland. Today a few of these languages remain, in non-contiguous areas, including far eastern Lakṝṣyāṇa and the southeastern Rǣrajāṇai, eastern Hūnakañjaiṭa, the Ṭilva mountains of Yayadalga, as well as the insular part of that diocese, and insular and coastal western Daihāgajña. | |||

** Maty languages (''matū ga dhāḍai'') – spoken in insular Lakṝṣyāṇa and Hūnakañjaiṭa, with outliers in the Korabi islands and the northern coast of Kumilanai; these areas were already its pre-Chlouvānem distribution. | |||

** Toiban languages (''tåyumbumi dhāḍai'') – historically spoken in Āturiyāmba, Jaṣmoeraus, inland Yayadalga, and northern Daihāgajña; today consisting of seven languages, the most spoken of whose is Kaɂapumi (''kaɂapumi dhāḍa''), spoken in central Jaṣmoeraus. | |||

** Ninat-Yowgi languages (''ninatuyovugi ga dhāḍai'') – historically spoken in Ājvajaiṭa, coastal Niyobajaiṭa, and central and southern Torašitā; was already being displaced from the latter area before Chlouvānemization by Toyubeshian speakers; today, they mostly remain in rural central and western Ājvajaiṭa. | |||

** Kumilanāyi (''kumilanāyi maiva'') — a Chlouvānem language spoken on Kumilanai and neighboring islands. | |||

** Tātanībāmi (''etek tatănibåŋ''; Chl. ''tātanībāmi dhāḍa'') — the main language spoken on the island of Tātanībāma, in most of the other islands in the Haichā group, and on Tahīɂa. Most languages of the Leyunakā islands - commonly known as Northern Leyunakī and Southern Leyunakī - are also related to Tātanībāmi, with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility. | |||

** Tandameipi (''nzɛk pɔb''; Chl.: ''tandameipi dhāḍa'') — the indigenous language of Tandameipa island, the southernmost of the Southeastern archipelago. It belongs to the Litoic branches of Outward Melau, itself a sub-branch of the Nduagaz languages mostly spoken in Queáten; the Nduagaz homeland itself is in southern Púríton, which makes these Outward Melau branches in Márusúturon the only Calémerian languages that before the age of colonization were spread between the Old and the New World. | |||

** Kaŋbo (''tūs kaŋbo''; Chl.: ''kalbo ga dhāḍa'') – a Heiga language (a branch of Outward Melau) spoken by three thousand people on Kaŋbotu island, the southernmost of the Leyunakā group. | |||

** Nukahucī (''ăŋkahisi phū''; Chl.: ''nukahucī dhāḍa'' or ''nukahucē ga lanāyān dhāḍa'') – a Litoic language spoken in the remote Nukahucē atolls, which constitute the smallest and least populous diocese of the Inquisition. | |||

* '''Northern Far East''' | |||

** Kaitajaši (''kaitajaši maivai'') — a dialect continuum spoken in most of the Northern Far Eastern tribunal, the historically Toyubeshian lands. | |||

** Modern Toyubeshian (''úat Vyānxāi'', ''úat Từaobát'', ''úat Xợothiāp'' or other names; Chl.: ''tayubešumi tāvyāṣusire dhāḍa'') — a koiné language for the dialects widely spoken in the inland areas of the former Toyubeshian lands. The common name is actually misleading, as it is not a daughter language of Toyubeshian (the former courtly language the loans in Chlouvānem and most local placenames came from), but of a related language<ref>The geographical name "Từaobát" [tˢɯː˥˩.aw˧.baθ˨˥], used by Modern Toyubeshian speakers from Hirakaṣṭē and eastern Moyukaitā for their land, is however a cognate of "Toyubeshi", from reconstructed Proto-Toyubeshian *təwjow bæsɨ. Both Toy. ''toyu'' and Modern Toy. ''từao'' mean "person"; Toy. ''beshi'' means "kingdom", but there is no Modern Toy. *bát, as it was most likely displaced by the Chlouvānem word (''púgakxalibána'' from ''pūgakṣarivāṇa'').</ref>: Classical Toyubeshian formed its own branch of the Tabian languages, while Modern Toyubeshian is part o the Tabi-Konashi branch. Due to the common koiné it is considered a single language; however, dialects on the eastern and western ends on the area are for the most part mutually unintelligible. Still, the varieties of Šimatoga and Hachitama constitute a sister branch, the Ki-Konashi languages, and are therefore often excluded. Counting together all of its varieties (and even when excluding Ki-Konashi), it is the most spoken non-Chlouvānem language of the Inquisition. | |||

** languages of the Outlying Islands of Haikamotē: vernaculars of the insular part of otherwise Chlouvānem-dominated Haikamotē, they are the only living descendants of Classical Toyubeshian. | |||

** Kowtic languages (''kotyumi dhāḍai'') – third branch of the Tabian languages, historically spoken in Naitontā and the northern coast of Torašitā. With the territory having been also settled and conquered by Toyubeshians, Kanoë-Pulin speakers in the far western part, and the Chlouvānem, today they include two mutually unintelligible languages spoken by about twenty thousand people in southern Naitontā. | |||

* '''East and Northeast''' | |||

** Hachitami-Šimatogi (''hachitami šimatogi no maivai'') — the Chlouvānem language spoken in most of the Eastern dioceses of Hachitama, Šimatoga, Utsunaya as well as northern Šiyotami and rural Padeikola. Often considered the northwesternmost extent of the Kaitajaši dialect continuum. | |||

** Northeastern creoles (''helaṣyuñci maivai'') – a family of related Chlouvānem-based creoles spoken as vernaculars across most of the Eastern and Northeastern tribunals. | |||

** Nalakhojumi (''üj nolomħoj''; Chl.: ''nalakhojumi dhāḍa'') — a Nahlan language spoken in most of the ethnic diocese of Nalakhoñjaiṭa by the Nalakhojai people. The city of Lānita, main urban area of the diocese, however, is almost entirely Chlouvānem-speaking. | |||

** Halyañumi (''üš hælyaney''; Chl.: ''halyañumi dhāḍa'') — a Nahlan language spoken by the Halyanyai people in the ethnic diocese of Halyanijaiṭa. Usage is highest in the northern part of the diocese and lowest in the metropolitan area of Īdisa, the largest inland metropolitan area of the Northeast. | |||

** Kūdavumi (''kowdao hüüj''; Chl.: ''kūdavumi dhāḍa'') — a Nahlan language spoken in the ethnic diocese of Kūdavīma by the Kūdavai people. While having only a small number of speakers, some words from it are common in the vernaculars of all of the Northeast, likely due to the historically nomadic nature of the Kūdavai. | |||

** Čathísǫ̃́g (''tłę́mí Čathísǫ̃́gbud''; Chl.: ''chandisēkumi dhāḍa'') — main vernacular in the ethnic diocese of Jįveimintītas. It is one of only two official languages of ethnic dioceses - together with Bazá - which is official in other countries, in this case it is the national language in the bordering country of Gwęčathíbõth as well as in the latter's northern neighbour C′ı̨bedǫ́s. | |||

* '''North''' | |||

** Hålvarami (''hålvarami maivai'') — a family of Chlouvānem-based creoles spoken in the dioceses of the Hålvaram plateau (Mārmalūdven, Doyukitama, Taibigāša, Kayūkānaki). | |||

** Dahelyumi (''dæhæng pop''; Chl.: ''dahelyumi dhāḍa'') — a language isolate (often subject to controversial classification theories) spoken by the Daheliai people of the ethnic diocese of Dahelijaiṭa, Northern tribunal, mostly in rural villages. | |||

** Qorfur (''ekişen ti qorfur''; Chl. ''kharpuryumi dhāḍa'') — a Balmudic language, part of the Fargulyn family and hence distantly related to Skyrdagor (Karaskyr branch) and the non-Chlouvānem Hålvarumi languages, spoken by the Qorfur people of the diocese of Vaskuvānuh (''Wask-wanu'' in Qorfur). Most Qorfur live, however, in the bordering country of Qorfurkweo or as the extremely large Qorfur diaspora, very numerous across Greater Skyrdagor. | |||

** Saṃhayoli (''saṃhayoli maiva'') — a Chlouvānem-based creole spoken in the diocese of Saṃhayolah and parts of Maichlahåryan. | |||

** [[Brono-Fathanic|Moamatemposisy]] (''ta fewåwanie ta mwåmahimbušihy''; Chl.: ''måmatempuñiyi dhāḍa'') — a variant of Brono-Fathanic spoken as a vernacular in the northern part of the diocese of Hivampaida. It is a triglossic area, as for official purposes, aside from Chlouvānem, Standard Bronic is also used. | |||

** In the whole North there are various pockets of [[Skyrdagor]] speakers due to the vicinity of Greater Skyrdagor, especially in Maichlahåryan (which was a part of Gorjan until the Kaiṣamā era). Skyrdagor varieties spoken here are mostly similar to Gorjonur, the variant spoken in the Greater Skyrdegan country of Gorjan. | |||

* '''Northwest''' | |||

** Luspori (''nmụñu Lụspori''; Chl. ''lyušparumi dhāḍa'') — the main vernacular of northern Srāmiṇajāṇai, a Maëbic language which is also the most spoken language of the neighboring country of Maëb and is also spoken natively in parts of Péráno, Aréntía, and Mašifúk to the west, as well as by seminomadic groups further west; it is a trade language in all countries of the southern shore of the Carpan Sea. The dialect spoken in Srāmiṇajāṇai is of the same variants of the Maëb Coast, which is the most spoken and most homogeneous dialectal group; however, there are obvious differences in what concerns the different political structures and dominant languages of Maëb and the Inquisition. | |||

''[West to be added]'' | |||

Some areas of the Inquisition do not have a major, local vernacular aside from the use of Classical Chlouvānem. The reason for all of these is that they were only recently (in the last two centuries) annexed to the Chlouvānem world and often there was no single local dominant language, so that there has been an often radical shift to Chlouvānem; some of these areas had also been Western colonies before being annexed by the Chlouvānem. These areas are: | |||

* all of the Northwest with the exception of the Luspori-speaking northern half of Srāmiṇajāṇai diocese. This includes the densely populated areas of Tārṣaivai and Līnajaiṭa, but also the virtually uninhabited deserts of Samvālšaṇṭrē and Ūnikadīltha. | |||

* the Nukahucē atoll chain, uninhabited before Chlouvānem settlement | |||

* the Kāmilbausa islands, also previously uninhabited | |||

* the far northern islands of Hokujaši and Aratāram as well as the inland taiga of Kēhamijāṇa, whose original inhabitants mostly shifted to Chlouvānem. Hokujaši island is however notable for the emergence on it of a peculiar koiné dialect of the Eastern Plain-Jade Coast continuum, as most of its original Chlouvānem settlers came from that area. This dialect, however, has been shrinking for decades and is today only spoken by a few people in rural areas, and many Hokujašeyi people do not even know of its existence. | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

===Historical dialects=== | ===Historical dialects=== | ||

==Phonology - Yāṃstarlā== | ==Phonology - Yāṃstarlā== | ||

: ''Main article: [[Chlouvānem/Phonology|Chlouvānem phonology]]'' | |||

Chlouvānem is phonologically very conservative from Proto-Lahob as it has not had a lot of changes - however, those few it had have had the effect of strongly raising the total number of phonemes, developing a few distinctions that, while not rare themselves, are rarely found all together in the same language. Chlouvānem has a large inventory in both consonants and vowels, and a fair amount of active morphophonemic saṃdhi processes.<!-- ===Phonological history=== | |||

Chlouvānem is, phonologically, very conservative when compared to Proto-Lahob, even if there is a reconstruction bias due to the fact that Chlouvānem was attested more than 2000 years earlier than all other Lahob languages of other branches. | |||

Especially in the consonant system, Chlouvānem is extremely close to Proto-Lahob: the dental, palatal, and velar stops are preserved completely unchanged (even if PLB palatals are reconstructed as true stops, instead of affricates); changes to their distribution have only occurred because of the assimilation of velar stops + *j into palatal stops and of the assimilation of dental stops + *r into retroflex ones. | |||

Labial stops are mostly unchanged, except for original *pʰ being reflected as '''ħ''', presumably through the intermediate stages */pʰ/ > */ɸ/ > */hʷ~χʷ~xʷ/ > /ħ/ (the same fate was followed by PLB *pw). Chlouvānem '''ph''' arises from PLB *kʷʰ. | |||

Labiovelar stops are the only ones that show the most changes: the aspirates have become true labial aspirates (*kʷʰ > pʰ; *ɡʷʱ > bʱ), while the plain ones have backed to /ʡ/ '''ƾ'''. | |||

PLB *l, *ŋ, *ŋʷ, and *ʕ (conventional representation for a laryngeal sound) all merged into /ɴ̆/ '''l'''. | |||

===Prosody=== | ===Prosody=== | ||

====Stress==== | ====Stress==== | ||

Stress in Chlouvānem is not phonemic and | Stress in Chlouvānem is not phonemic and typically very weak.<br/> | ||

* The last long vowel in a word is stressed, unless it is word-final ''' | In formal Chlouvānem, stress position is, in most cases, predictable, determined by long vowels and verbal roots: | ||

* The last long vowel in a word is stressed, unless it is word-final '''ē'''; | |||

* Verbal roots always carry either the main stress or secondary stress (depending on the previous rule); | * Verbal roots always carry either the main stress or secondary stress (depending on the previous rule); | ||

* In words with no long vowels, the third-to-last syllable is stressed, unless the fourth-to-last is the stressed part of a verbal root; | * In words with no long vowels, the third-to-last syllable is stressed, unless the fourth-to-last is the stressed part of a verbal root; | ||

* Compound words have secondary stress on each vowel that would have primary stress if it were an isolated word, except if immediately preceding another (primarily or secondarily) stressed vowel; in that case, the stress moves one syllable backwards unless it would lead to another such situation of consecutive stress (e.g. */ˌSSˌSˈSS/ → /ˌSSSˈSS/ and not **/ˌSˌSSˈSS/). | * Compound words have secondary stress on each vowel that would have primary stress if it were an isolated word, except if immediately preceding another (primarily or secondarily) stressed vowel; in that case, the stress moves one syllable backwards unless it would lead to another such situation of consecutive stress (e.g. */ˌSSˌSˈSS/ → /ˌSSSˈSS/ and not **/ˌSˌSSˈSS/). | ||

** Some noun-forming suffixes, especially for specialized terminology, are always stressed, such as ''-bida''/''-buda'' in chemical elements. | |||

* Final ''-oe'' and ''-ai'' are always stressed, except when ''-ai'' is a plural marker - thus ''lunai'' "tea" is stressed on the ending, while ''kitai'' "houses" on the first syllable. | * Final ''-oe'' and ''-ai'' are always stressed, except when ''-ai'' is a plural marker - thus ''lunai'' "tea" is stressed on the ending, while ''kitai'' "houses" on the first syllable. | ||

Some examples of stress placement: | Some examples of stress placement: | ||

* ''dilṭha'' "desert" [ | * ''dilṭha'' "desert" [ˈdiɴ̆ʈʰa] | ||

* ''upānāraḍa'' "seminary" [upaːˈnaːʀaɖa] | * ''upānāraḍa'' "seminary" [upaːˈnaːʀaɖa] | ||

* ''ñulge'' "to crawl (monodirectional)" [ˈɲuŋge] | * ''ñulge'' "to crawl (monodirectional)" [ˈɲuŋge] | ||

* '' | * ''ñogē'' "(s)he/it crawls" [ˈɲogeː] | ||

* ''ñuganāja'' "we crawled" [ˌɲugaˈnaːɟ͡ʑa] | * ''ñuganāja'' "we crawled" [ˌɲugaˈnaːɟ͡ʑa] | ||

* ''driturkye'' "[I've been told that] (it) was done against you" [ˈdʀʲituˤkje] | * ''driturkye'' "[I've been told that] (it) was done against you" [ˈdʀʲituˤkje] | ||

* '' | * ''švaghṛṣṭrausis'' "tunnel" [ˌɕʋagʱʀ̩ˈʂʈʀaʊ̯sis] | ||

* '' | * ''švaghṛṣṭraustammikeika'' "tunnel railway station" [ˌɕʋagʱʀ̩ʂʈʀaʊ̯sˌtammiˈkeɪ̯ka] | ||

Words with unpredictable stress often have regional variations. For example, ''tandayena'' "spring (season)" is stressed as [tandaˈjena] in most of the East and Northeast but as regular [tanˈdajena] almost anywhere else (in this particular case, the irregular stress is actually closer to the etymology, as it is a borrowing from a | Words with unpredictable stress often have regional variations. For example, ''tandayena'' "spring (season)" is stressed as [tandaˈjena] in most of the East and Northeast but as regular [tanˈdajena] almost anywhere else (in this particular case, the irregular stress is actually closer to the etymology, as it is a borrowing from a Toyubeshian compound word). | ||

====Intonation==== | ====Intonation====--> | ||

== | ==Writing system - Jīmalāṇa== | ||

The | [[File:Chlouvānem-script-parts.png|thumbnail|The word ''chlǣvānem'' in the language's native script, with the parts colour-coded according to function.]] | ||

Chlouvānem has been written since the early 5th millennium in an abugida called ''chlǣvānumi jīmalāṇa'' ("Chlouvānem script", the noun ''jīmalāṇa'' is actually a collective derivation from ''jīma'' "character"), developed with influence of the script used for the [[Lällshag|Lällshag language]]. The orthography for Chlouvānem represents how it was pronounced in Classical times, but it's completely regular to read in all present-day local pronunciations.<br/> | |||

The Chlouvānem alphabet is distinguished by a large number of curved letter forms, arising from the need of limiting horizontal lines as much as possible in order to avoid tearing the leaves on which early writers wrote. A few glyphs have diagonal or vertical lines, but in pre-typewriting times there was a tendency to have them slightly curved; however, horizontal lines are today found in the exclamation and question marks (which are early modern inventions) and in mathematical symbols; the ''priligis'', or inherent-vowel-cancelling sign, is also nowadays often represented as a horizontal stroke under the consonant, following the most common handwriting styles; however, formerly it was (and formally still is) written as a subscript circumflex. | |||

Being an abugida, vowels (including diphthongs) are mainly represented by diacritics written by the consonant they come after (some vowel diacritics are actually written before the consonant they are tied to, however); '''a''' is however inherent in any consonant and therefore does not need a diacritic sign. Consonant clusters are usually representing by stacking the consonants on one another (with those that appear under the main consonant sometimes being simplified), but a few consonants such as '''r''' and '''l''' have simplified combining forms. The consonant '''ṃ''' is written with diacritics and can't appear alone. There are also special forms for final '''-m''', '''-n''', '''-s''', and '''-h''' due to their commonness; other consonants without inherent vowels have to be written with a diacritic sign called ''priligis'' (deleter), which has the form of a subscript circumflex or, most commonly, subscript horizontal stroke, or as conjunct consonants.<br/> | |||

The combinations ''lā vā yā ñā pā phā bhā'' are irregularly formed due to the normal diacritic ''ā''-sign being otherwise weirdly attached to the base glyph. There is, furthermore, a commonly used single-glyph abbreviation for the word ''lili'', the first-person singular pronoun. | |||

The romanization used for Chlouvānem avoids this problem by giving each phoneme a single character or digraph, but it stays as close as possible to the native script. Aspirated stops and diphthongs are romanized as digraphs and not by single letters; geminate letters, which are represented with a diacritic in the native script, are romanized by writing the consonant twice - in the aspirated stops, only the first letter is written twice, so /ppʰ/ is '''pph''' and not *phph. | |||

Romanization table in native alphabetical order: | |||

{| class="redtable lightredbg" align="center" style="text-align: center; width: 40%" | | |||

= | |||

|- | |- | ||

! '''''m''''' !! '''''p''''' !! '''''ph''''' !! '''''b''''' !! '''''bh''''' !! '''''v''''' !! '''''n''''' !! '''''t''''' !! '''''th''''' !! '''''d''''' !! '''''dh''''' !! '''''s''''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | {{IPA|/m/}} || {{IPA|/p/}} || {{IPA|/pʰ/}} || {{IPA|/b/}} || {{IPA|/bʱ/}} || {{IPA|/ʋ/}} || {{IPA|/n/}} || {{IPA|/t̪/}} || {{IPA|/t̪ʰ/}} || {{IPA|/d̪/}} || {{IPA|/d̪ʱ/}} || {{IPA|/s/}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

! '''''ṇ''''' !! '''''ṭ''''' !! '''''ṭh''''' !! '''''ḍ''''' !! '''''ḍh''''' !! '''''ṣ''''' !! '''''ñ''''' !! '''''c''''' !! '''''ch''''' !! '''''j''''' !! '''''jh''''' !! '''''š''''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | {{IPA|/ɳ/}} || {{IPA|/ʈ/}} || {{IPA|/ʈʰ/}} || {{IPA|/ɖ/}} || {{IPA|/ɖʱ/}} || {{IPA|/ʂ/}} || {{IPA|/ɲ/}} || {{IPA|/c͡ɕ/}} || {{IPA|/c͡ɕʰ/}} || {{IPA|/ɟ͡ʑ/}} || {{IPA|/ɟ͡ʑʱ/}} || {{IPA|/ɕ/}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

! '''''y''''' !! '''''k''''' !! '''''kh''''' !! '''''g''''' !! '''''gh''''' !! '''''ṃ''''' !! '''''ɂ''''' !! '''''h''''' !! '''''ħ''''' !! '''''r''''' !! '''''l''''' !! '''''i''''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | {{IPA|/j/}} || {{IPA|/k/}} || {{IPA|/kʰ/}} || {{IPA|/ɡ/}} || {{IPA|/ɡʱ/}} || {{IPA|/ɴ/}} || {{IPA|/Ɂ/}} || {{IPA|/ɦ/}} || {{IPA|/ħ/}} || {{IPA|/ʀ/}} || {{IPA|/ɴ̆/}} || {{IPA|/i/}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

! '''''ī''''' !! '''''į''''' !! '''''u''''' !! '''''ū''''' !! '''''ų''''' !! '''''e''''' !! '''''ē''''' !! '''''ę''''' !! '''''o''''' !! '''''æ''''' !! '''''ǣ''''' !! '''''a''''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | {{IPA|/iː/}} || {{IPA|/i̤/}} || {{IPA|/u/}} || {{IPA|/uː/}} || {{IPA|/ṳ/}} || {{IPA|/e/}} || {{IPA|/eː/}} || {{IPA|/e̤/}} || {{IPA|/ɔ/}} || {{IPA|/ɛ/}} || {{IPA|/ɛː/}} || {{IPA|/ä/}} | ||

| | |- | ||

! '''''ā''''' !! '''''ą''''' !! '''''ai''''' !! '''''ąi''''' !! '''''ei''''' !! '''''ęi''''' !! '''''oe''''' !! '''''au''''' !! '''''ąu''''' !! '''''å''''' !! '''''ṛ''''' !! '''''ṝ''''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

| {{IPA|/äː/}} || {{IPA|/ɑ̤/}} || {{IPA|/aɪ̯/}} || {{IPA|/a̤ɪ̯/}} || {{IPA|/eɪ̯/}} || {{IPA|/e̤ɪ̯/}} || {{IPA|/ɔə̯/}} || {{IPA|/aʊ̯/}} || {{IPA|/a̤ʊ̯/}} || {{IPA|/ɔ/}} || {{IPA|/ʀ̩/}} || {{IPA|/ʀ̩ː/}} | |||

|} | |} | ||

Some orthographical and phonological notes: | Some orthographical and phonological notes: | ||

* /n/ [ŋ] is written as '''l''' before '''k g kh gh n'''. Note that in many local varieties '''lk lkh lg lgh''' are actually [ɴq ɴqʰ ɴɢ ɴɢʱ], with the stop assimilating to '''l''' and not vice-versa, and thus analyzed as /ɴ̆k ɴ̆kʰ ɴ̆g ɴ̆gʱ/. | * {{IPA|/n/ [ŋ]}} is written as '''l''' before '''k g kh gh n'''. Note that in many local varieties '''lk lkh lg lgh''' are actually {{IPA|[ɴq ɴqʰ ɴɢ ɴɢʱ]}}, with the stop assimilating to '''l''' and not vice-versa, and thus analyzed as {{IPA|/ɴ̆k ɴ̆kʰ ɴ̆g ɴ̆gʱ/}}. | ||

* {{IPA|/ɴ̆ː/}} may be written as either '''ll''' or '''ṃl'''; the latter is used when compounding two morphemes, the first of which ends in any nasal consonant except for '''l''' itself. | |||

* Vowels do not have non-diacritical forms; when word-initial, they are written on the glyph for '''ɂ'''. In Classical Chlouvānem and in many modern pronunciations, word-initial vowels are actually always preceded by an allophonic glottal stop. Such glyphs are, however, romanized simply as e.g. ''a'', not *ɂa. | |||

Letter names are formed with simple rules: | Letter names are formed with simple rules: | ||

* All consonants apart from '''l''', '''r''', and aspirated stops form them with CaCas, e.g. '''s''' is ''sasas'', '''m''' is ''mamas'', '''b''' is ''babas'' and so on. '''ɂ''' is written ''aɂas''. | * All consonants apart from '''l''', '''r''', and aspirated stops form them with CaCas, e.g. '''s''' is ''sasas'', '''m''' is ''mamas'', '''b''' is ''babas'' and so on. '''ɂ''' is written ''aɂas''. | ||

* Aspirated stops form them as CʰeCas, e.g. '''bh''' is ''bhebas'', '''ph''' is ''phepas'', and so on. | * Aspirated stops form them as CʰeCas, e.g. '''bh''' is ''bhebas'', '''ph''' is ''phepas'', and so on. | ||

* '''l''' is '' | * '''l''' is ''lǣlas'' and '''r''' is ''rairas''. '''ṃ''' is, uniquely, ''nālkāvi''. | ||

* Short vowels are VtV*s, where the second V is ''a'' for '''æ''' (''ætas''), ''i'' for '''e''' (''etis''), and ''u'' for '''o''' (''otus''). | * Short vowels are VtV*s, where the second V is ''a'' for '''æ''' (''ætas''), ''i'' for '''e''' (''etis''), and ''u'' for '''o''' (''otus''). | ||

* Long vowels are vowel + ''-nis'' if unrounded (''īnis'', '' | * Long vowels are vowel + ''-nis'' if unrounded (''īnis'', ''ēnis'', ''ānis''), but '''ū''', being rounded, is ''ūmus''. Oral diphthongs all have diphthong + ''-myas'' (''aimyas'', ''eimyas''…); '''å''' is counted as a diphthong and as such it is ''åmyas''. | ||

* Breathy-voiced vowels are vowel + /ɦ/ + vowel + s ('' | * Breathy-voiced vowels are vowel + {{IPA|/ɦ/}} + vowel + s (''ihis'', ''ahas'', ''uhus'', but ''ehas''). Breathy-voiced diphthongs are diphthong + {{IPA|/ɕ/}} + ''as'' (''ąišas'', ''ęišas'', ''ąušas''). | ||

===o and å=== | ===o and å=== | ||

In today's standard Chlouvānem, the letters '''o''' and '''å''' are homophones, being both pronounced /ɔ/: their distribution reflects their origin in Proto-Lahob (PLB), with '''o''' deriving from PLB *aw and *ow, and '''å''' from either *a umlauted by a (lost) *o in a following syllable, or, most commonly, from the sequences *o(ː)wa, *o(ː)fa, *o(ː)wo, or *o(ː)fo. | In today's standard Chlouvānem, the letters '''o''' and '''å''' are homophones, being both pronounced {{IPA|/ɔ/}}: their distribution reflects their origin in Proto-Lahob (PLB), with '''o''' deriving from PLB *aw and *ow, and '''å''' from either *a umlauted by a (lost) *o in a following syllable, or, most commonly, from the sequences *o(ː)wa, *o(ː)fa, *o(ː)wo, or *o(ː)fo. | ||

Most Chlouvānem sources, however, classify '''å''' as a ''diphthong'': Classical Era sources nearly accurately describe it as / | Most Chlouvānem sources, however, classify '''å''' as a ''diphthong'': Classical Era sources nearly accurately describe it as {{IPA|/ao̯/}}, later monophthongized to {{IPA|[ʌ]}} or {{IPA|[ɒ]}} and merged with {{IPA|/ɔ/}} - in fact, most daughter languages have the same reflex for both '''o''' and '''å'''. A few grammarians think that '''å''' was originally the long version of '''o''', but this hypothesis is disputed as '''å''' does not pattern with the other long vowels (e.g. '''o''' does not lengthen into it because of synchronic lengthening; also it is grouped with diphthongs in the alphabetic order instead of coming just after '''o''', as other long vowels do). Some kind of distinction in the pronunciations of Classical Chlouvānem must have been preserved until early modern times, as both are found in adapting foreign words - usually '''å''' transcribes more open vowels than '''o'''. | ||

A spelling-based pronunciation distinction (with '''å''' being {{IPA|[ɔ]}} and '''o''' being {{IPA|[o(ː)]}}) has been recently spreading among young speakers in the large metropolitan areas of the Jade Coast. | |||

===Notes on romanization=== | ===Notes on romanization=== | ||

The romanization here used for Chlouvānem is adapted to English conventions, with a few adjustments made to better reflect how written Chlouvānem looks on Calémere: | The romanization here used for Chlouvānem is adapted to English conventions, with a few adjustments made to better reflect how written Chlouvānem looks on Calémere: | ||

* Even if the Chlouvānem script uses scriptio continua and marks minor pauses (e.g. comma and semicolon) with a space between the sentences and a punctuation mark with following space, every word is divided when romanized, including particles. The only | * Even if the Chlouvānem script uses scriptio continua and marks minor pauses (e.g. comma and semicolon) with a space between the sentences and a punctuation mark with following space, every word is divided when romanized, including particles. The only exceptions to this are compound verbs, which are written as a single word nevertheless (e.g. ''yųlakemaityāke'' "to be about to eat" '''not''' *yųlake maityāke). English punctuation marks are used in basic sentences, including a distinction between comma and semicolon. In longer texts, particularly in the "examples" section, ''':''' will be used to mark a comma-like pause (a space in the native script) and '''।।''' will be used for a full-stop-like pause (written very similarly to ।। in the native script). | ||

* As the Chlouvānem script does not have lettercase, no uppercase letters are used in the romanization, except to disambiguate cases like '' | * As the Chlouvānem script does not have lettercase, no uppercase letters are used in the romanization, except to disambiguate cases like ''lairē'' (noun: sky, air) and ''Lairē'' (female given name), and for proper nouns written in isolation. | ||

===Abbreviations=== | |||

: <small>''In this section, pure transcriptions are used. Superscript letters mark vowel diacritics; subscript letters mark conjoined consonants; a mid dot after the consonant (for '''m''', '''s''', and '''h''' only) marks a special final form; a dash marks the deletion mark of inherent vowels, and a tilde marks the abbreviation mark.''</small> | |||

The Chlouvānem script has a specific, tilde-shaped, mark called ''aniguṃsṛṣūs'' which used to mark an abbreviation. In most cases, only the first and the last consonant (in some cases, the first two and the last, or the first one and the last two) of a word are written (including those normally written as part of a conjunct), without vowels, with the abbreviation sign written on top of the last letter. For example, the word ''dirūnnevya'' (grammatical case), written normally as '''d<sup><small>i</small></sup>r<sup><small>ū</small></sup>n<sub><small>n</small></sub><sup><small>e</small></sup>v<sub><small>y</small></sub>''', is abbreviated to '''dỹ''' or '''drỹ''', less commonly to '''dvỹ'''; ''nūlastām'' (money), '''n<sup><small>ū</small></sup>ls<sub><small>t</small></sub><sup><small>ā</small></sup><sub><small>m</small></sub>''', is abbreviated to '''nm̃''' or '''nlm̃'''.<br/> | |||

Cases are typically written without vowels (which means many of them are not differentiated at all). | |||

Exceptions to the above include: | |||

* Many officially sanctioned abbreviations, which are made of different consonants or even consonant-vowel combinations. Examples include all three-letter-codes for dioceses (e.g. ''Nanašīrama'' diocese, '''nnš<sup><small>ī</small></sup>rm''', abbreviated as '''nnš̃'''), and all measurement units (e.g. ''brujñam'' (fathom; ~2.5975 m), '''b<sub><small>r</small></sub><sup><small>u</small></sup>j<sub><small>ñ</small></sub>m·''', abbreviated as '''br̃<sup><small>u</small></sup>'''). Measurement units are written with the abbreviation mark when inside sentences, without it otherwise. | |||

* Syllabic abbreviations, which are not treated as abbreviations but as regular words, complete with regular internal saṃdhi changes, and are in fact an extremely common reality in daily life in the Inquisition (e.g. ''mugada'' ← '''''mu'''rkadhānāvīyi '''ga'''ltarlīltumi '''da'''rañcamūh'' "Inquisitorial Railway Group"; ''mugišca'' ← '''''mu'''rkadhānāvīyi '''giṣ'''ṭarumi '''ca'''mūh'' "Inquisitorial Youth Union", i.e. the Chlouvānem Komsomol). | |||

===Writing=== | ===Writing=== | ||

The Chlouvānem script is almost entirely composed of curved lines as, initially, it was written on leaves with reeds ('' | The Chlouvānem script is almost entirely composed of curved lines as, initially, it was written on leaves with reeds (''ħålka'', pl. ''ħålkai'') or brushes (''lattah'', pl. ''lattai''). With the invention, in the late 5th millennium, of paper (traditional Chlouvānem paper or ''mirtah'' is handmade by fibres from various types of wooden bushes; traditional papermaking is still important today as formal handwritten documents are usually written on traditional paper), the use of reeds or brushes often became region-dependant; the reeds of the ''grāṇiva'' plant became the dominant writing tool in most of the plains, as this plant abundantly grows by the river shores; in the Jade Coast, brushes (whose "hair" are actually fibres of wetland plants such as the ''jalihā'') were preferred.<br/> | ||

Today, pens ('' | Today, pens (''titeh'', pl. ''tityai'') are the main writing tool together with graphite pencils (''bauteh'', pl. ''bautyai''). Non-refillable dip pens were the first to be introduced - an Evandorian invention that was "seized" by the Chlouvānem during the early 7th millennium occupation of Kátra, a Nordûlaki colony on Ovítioná - and with the advent of industrial papermaking they became more and more popular; fountain pens were evolved from them first in Nivaren, and in 6291 (3785<sub>12</sub>) the first fountain pen manufacturer in the Inquisition opened. Ballpoint pens are, on Calémere, a much recent invention, and first appeared in the Inquisition about forty years ago. They are still not used as much as fountain pens when writing on normal paper.<br/> | ||

The traditional '' | The traditional ''ħålkai'' and ''lattai'' have not disappeared, as both are still found and used - even if only with traditional handmade paper. Both are commonly used for calligraphy as well as in various other uses: for example, [[w:Banzuke|banzuke]] papers for tournaments of most traditional sports are carefully handwritten with reed pens, as are many announcements by local temples (written with either reed pens or brushes); a newer type of brush pen (much like Japanese [[w:Fudepen|fudepen]]s) has proven to be particularly popular even in everyday use (both with traditional and modern industrial paper) in the Jade Coast area - many Great Inquisitors from there, including incumbent Hæliyǣšavi Dhṛṣṭāvāyah ''Lairē'', have been seen writing official document with such kind of pens. | ||

Pens themselves are often artisanal products and in many cases Chlouvānem customers prefer refillable ones; many people have tailor-made sets of pens and almost always carry one with them. | Pens themselves are often artisanal products and in many cases Chlouvānem customers prefer refillable ones; many people have tailor-made sets of pens and almost always carry one with them. | ||

==Morphology - Maivāndarāmita== | ==Morphology - Maivāndarāmita== | ||

: ''Main article: [[Chlouvānem/Morphology|Chlouvānem morphology]]'' | |||

'' | Chlouvānem morphology (''maivāndarāmita'') is complex and synthetic, with a large number of inflections. Five parts of speech are traditionally distinguished: nouns, verbs, pronouns, numerals, and particles.<br/> | ||

Most inflections are suffixes, with stem-internal vowel apophony also playing a role. Prefixing inflections are almost exclusively reduplications, though there is a large number of derivational prefixes which play a major role in the language. | |||

==Syntax - Kilendarāmita== | |||

: ''Main article: [[Chlouvānem/Syntax|Chlouvānem syntax]]'' | |||

Chlouvānem is a mostly [[w:Synthetic language|synthetic]], [[w:Topic-prominent language|topic-prominent]], and almost exclusively head-final language. It has an [[w:Austronesian alignment|Austronesian-type morphosyntactic alignment]] and a topic-comment word order, with OSV or SOV syntax being chosen according to how the topic itself is marked. | |||

==Vocabulary== | |||

Due to the history and the present status of Chlouvānem, its vocabulary draws from a wide range of sources and is characterized by a large number of geosynonyms, a consequence of its role as a Dachsprache on a very large area with many different historical substrata and vernaculars. | |||

''' | The percentages of various sources depend on the definition, particularly for what concerns the Lahob stock. If roots are counted, Lahob-inherited roots may be as low as 30 to 35% of the total vocabulary, but Lahob vocabulary constitutes a much higher percentage due to the very high productivity of verbal roots (mostly of Lahob origin) with the various derivational prefixes and suffixes.<br/> | ||

Non-Lahob roots are traditionally classified in the following way, depending on their geographical origin: | |||

* Words from pre-Inquisitorial indigenous languages of the Plain and of the Jade Coast (''dhoyi olelų maivai''), most of them sparsely attested such as Ancient Yodhvāsi, Tamukāyi, Laiputaši, Old Kāṃradeši, and Aṣasṝkhami. possibly forming the majority of roots. Early Chlouvānem, soon after the Ur-Chlouvānem settled in the lower Nīmbaṇḍhāra plain, was enriched by a very large number of roots taken from local languages. Such words are found in all semantic fields, and are particularly numerous in words for the family, plants, animals, and the earliest artifacts and practices of settled civilization. | |||

* Lällshag words (''lælšñenīs maivai'') – divided in two large groups, that is, words that were borrowed from Lällshag in ancient times, pertaining to many semantic fields but mostly early technology (the Lällshag people were the first urban civilization in that area of the world) or used as more formal, higher-styled alternatives to Lahob or pre-Chlouvānem words; and a second group of modern scientific vocabulary that has been being coined since the start of the modern era from Lällshag roots; these often show more semantical drift, as they are often borrowed in more abstract or specific senses. | |||

* Southern, Far Eastern, Toyubeshian, and Dabuke words (''maichleyuñcų lallanaleiyuñcų no tayubešenīs no dabukyenīs no maivai'') – that is, words taken from the languages of the territories of the first millennium of expansion of the Chlouvānem world. They mostly relate to natural and cultural features of those territories, with Toyubeshian words being particularly important because they form most of the Chlouvānem words relating to a temperate climate area; whatever proto-Lahob roots that had survived the Ur-Chlouvānem migrations were mostly readapted to the tropical climate they had settled in; as a striking example, the Chlouvānem terms for the four main temperate seasons are all Toyubeshian borrowings. | |||

* Skyrdegan words (''ṣurṭāgyenīs maivai'') – the Skyrdegan civilization was the first one too large and strong to be fully Chlouvānemized, and the languages of the Chlouvānem and Skyrdegan people have, for the last eight hundred years, exchanged words for their habitats (tropical to equatorial for the Chlouvānem; temperate to subpolar for the Skyrdegan) and all new discoveries in their cultural spheres; this keeps happening today, with the Skyrdegan countries being politically more open than the Inquisition and many Western cultural concepts reaching the Inquisition only through Skyrdegan mediation. The few words of Bronic and Qualdomelic origin are usually added to this group, despite the very different history (Brono and Qualdomailor were historically minor, less influential countries, whose present identity has been thoroughly influenced by the Chlouvānem spreading the Yunyalīlti faith among them).<br/>Words from Old Hålvarami are sometimes counted in this group, despite Old Hålvarami being a Fargulyn language related to Skyrdagor but from a different branch; the reason is that Old Hålvarami initially mediated the contact between the Chlouvānem and the Skyrdegan worlds, resulting in borrowings such as most notably ''ṣurṭāgah'' "Skyrdagor" (borrowed from Skyrdagor into Pre-Old Hålvarami and then into Chlouvānem) and ''pāṣratis'' (Calémerian cannabis plant). | |||

* "Discovery-era" words (''tatalunyavyāṣi maivai'') – words from the age of overseas discoveries<ref>It is not proper to speak of "colonization age" for the Chlouvānem; unlike the Western world, Chlouvānem countries (and mostly the Lūlunimarti Republic) had a very small overseas colonial presence, and mostly concentrated in some areas of western Ovítioná. In other continents (and mostly eastern Védren, Fárásen, and Queáten only), Chlouvānem presence was basically limited to a few coastal trade stations.</ref>, that is, related to flora, fauna, and cultures of continents new to the Chlouvānem; many of them have become in common use due to crops being now cultivated on the Inquisition's territory. | |||

** Western words (''yacvāni maivai'') – a subset of Discovery-era words, including those that have their origins in the more technologically advanced civilizations of Evandor, the Spocian cultural sphere of northern Védren, and the Nâdja- and Kenengyry-speaking world. This is overall a small group, but includes many modern international words. A particularly notable category is the one of borrowings from Kenengyry languages, especially [[Soenjoan]] and [[Kuyugwazian]], first entering urban slang (as Kaiṣamā-era settlement of Kenengyry people in the Inquisition often made them a notable urban minority in most large cities of the Inquisition), then spreading to the standard language with words such as ''najūba'' "(romantic) date", ''tuyiba'' "hoodie", or ''calghyula'' "circle of friends".<br/>As for words actually originating in the West (Evandor and Evandorian colonies), a large number of them, particularly for the earliest ones, come from [[Auralian]], as Auralia was the first Western nation the Chlouvānem had fairly regular contacts with<ref>Such terms include food, such as ''ṣryūvas'' "pomegranate" (Aur. ''sryuf''), ''braṇyājas'' "sweet bite-sized pastries" (Aur. ''brenayyaz''), or ''taħivkam'' "cold cuts" (most commonly head cheese) (Aur. ''taḥifket'' "ham", originally borrowed as the plurale tantum ''taħivkāt'', from which the singular form was developed by analogy); Western elements such as ''arṭīlas'' (Asèl, the Aselist deity; Aur. ''Arṣil''); and miscellaneous stuff such as ''jabræktas'' "cigarette" (Aur. ''zbrekt'' "tobacco") or ''lyoca'' "(recreational) drug" (from earlier ''berlyotsas'', from (today obsolete) Aur. ''brilyuts'', originally "alcohol", particularly the one drunk by sailors).</ref>. Nordûlaki and, especially, Cerian borrowings are much more recent, though the prevalence of Cerian as modern Calémere's main lingua franca, only rivalled by Chlouvānem itself, has led many toponyms in Chlouvānem to be adaptations of the Cerian names. | |||

=== | ===Honorific speech=== | ||

Politeness is lexically encoded in Chlouvānem through means of different honorific terms that are used depending on the listener. Most often, that means that there is a neutral or humble term for the speaker's side and a more respectful term for the listener's side: one area where this is very common is about body parts. | |||

It is of great anthropological and historical interest how very often, for nouns, the higher register term is of Lahob origin, having cognates in most (if not all) other languages of the family, while the lower terms (i.e. the neutral or humble ones) are typically non-Lahob, from other indigenous languages of the Plain. This is consistent with Chlouvānem having been, in the centuries right after the Chlamiṣvatrā's lifetime, the local lingua franca and possessing a higher, and sacred, status. | |||

Verbs show a similar distinction, though with many verbs the humble and the neutral forms are the same. In many cases, if a verb has a respectful equivalent then each derived form can be made respectful by switching the root verb (e.g. ''muṣke'', ''paṣmuṣke'' "to ask"; "to interrogate" → respectful forms ''pṛdhake'', ''paṣpṛdhake''). For nouns this varies, but as a general rule all profession-related nouns are always made with ''lila'' and never with ''emmā'' or ''imati''. | |||

{| class="redtable lightredbg" style="text-align: center;" | |||

|+ Most common terms with honorific speech alternatives <small>(in Latin alphabetical order)</small> | |||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! English !! Humble<br/><small>(''nīnamaiva'' or ''emmāmaiva'')</small> !! Neutral<br/><small>(''nūṣṭhamaiva'' or ''lilamaiva'')</small> !! Respectful<br/><small>(''imatimaiva'')</small> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! advice, tip, suggestion | ||

| titta || colspan=2 | smārṣas | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! to ask | ||

| rowspan=2 | yacce<br/><small>(''yacē, icek, iyaca'')</small><br/><small>(also ''yaccechlašake'')</small> || muṣke<br/><small>(''miṣē, muṣek, umuṣa'')</small> || pṛdhake<br/><small>(''pardhē, pṛdhek, apṛdha'')</small> | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! to command, order | ||

| spruvyake<br/><small>(''sprovyē, spruvyek, uspruvya'')</small> || hāryaṃdṛke<br/><small>(''hāryaṃdarē, hāryaṃdṛk, hāryaṃdadrā'')</small><br/>spruvyake | |||

|- | |- | ||

! cup of tea<ref>The humble-neutral form is almost never used (and in fact means "cup with tea"), as ''ñimbha'' is typically found in teahouses' and restaurants' menus, and used by waiters towards customers.</ref> | |||

| colspan=2 |<small>''lunąis lā galtha''</small> || ñimbha | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! to do, act, make | ||

| chlašake<br/><small>(''chlašē, chlašek, achlaša'')</small> || colspan=2 | dṛke<br/><small>(''darē, dṛk, dadrā'')</small> | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! ear | ||

| baɂim || colspan=2 | minnūlya | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! eye | ||

| ṭaɂika || mešīs<br/>nāhim <small>''(medical)''</small> || mešīs | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! father | ||

| colspan=2 | bunā || tāmvāram | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! food | ||

| colspan=2 | yųlgis || enekīh | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! foot | ||

| kilka || colspan=2 | junai | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! gift | ||

| comboe<br/><small>''the speaker receives''</small> || yauṭoe || dvyauṇoe<br/><small>''the listener, or respected third party, receives''</small> | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! to give | ||

| colspan=2 | męlike<br/><small>''(męlyē, męlik, emęlya)''</small> || naiṣake<br/><small>''(naiṣē, naiṣek, anaiṣa)''</small> | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! hand | ||

| tassa || colspan=2 | dhāna | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! husband | ||

| snūṣṭras || colspan=2 | šulañšoe | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! leg | ||

| miṇṭha || colspan=2 | pājya | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! to meet | ||

| colspan=2 | vuryake<br/><small>''(voryē, vuryek, uvurya)''</small> || naimake<br/><small>''(naimē, naimek, anaima)''</small> | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! meeting, encounter | ||

| colspan=2 | voryanah || naimoe | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! mother | ||

| colspan=2 | meinā || nāḍima | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! person | ||

| lila<br/>emmā || lila || imati | |||

|- | |- | ||